ABSTRACT

Sustainable innovations have the potential to drive market systems and behaviours towards greater sustainability, yet the collective efforts of various network actors involved in shaping markets for these innovations are poorly understood. This paper examines the activities that public-private innovation network actors engage in when shaping markets for a side-stream-based sustainable innovation. A qualitative case study exploring a technological sustainable innovation that enables the valorisation and reuse of side-streams is used to illustrate the complex nature of market-shaping activities at the crossroads of different industries. The findings indicate that developing sustainable innovations and shaping markets at the intersection of traditionally separate industries require both side-stream producers and side-stream users to align and synchronise their market-shaping processes. To implement these alignments, different forms of intermediation are needed: brokering for exchange, configuring the technological system, and facilitating narrative construction. The public-private innovation network plays a key role in this intermediation by bringing together various actors, connecting their activities, and reconciling divergent perspectives. Our study contributes to a better understanding of market-shaping in a networked, multi-industry setting and the importance of intermediation through public-private innovation networks.

1. Introduction

Sustainable innovations are central in the transitioning towards more sustainable markets. Hence, it is not surprising that sustainable innovations (i.e. new or modified products, processes, or services that aim to have positive impact on sustainable development) have received increasingly wide attention both in academia and industry (Adams et al. Citation2016; Cillo et al. Citation2019). There is a sense of urgency to create and implement sustainable innovations with higher pace and better results. However, there are significant delays and problems in their adoption and diffusion. These problems have been linked to the complex and systemic nature of sustainable innovations, causing high risks and uncertainties for companies (Hall and Wagner Citation2012). Especially environmentally sustainable innovations, which our study focuses on, can often entail multifaceted and radical technological change, requiring fundamental changes to raw materials, production processes, and to the whole set of market operations (De Marchi Citation2012). Furthermore, sustainable innovations must compete with established technologies that are usually supported by the practices, norms, and regulations of the existing markets (Geels, Hekkert, and Jacobsson Citation2008; Kemp, Schot, and Hoogma Citation1998). Consequently, building or shaping a supportive environment is relevant especially for radical sustainable innovations, as they require transformative change at wider societal levels (Geels Citation2002; Köhler et al. Citation2019). To realise such changes, firms need to partner with others to collaboratively influence their environment and build a favourable setting where their innovations can succeed (Musiolik, Markard, and Hekkert Citation2012).

While there is substantial evidence that network collaboration is important for the adoption and diffusion of sustainable innovations (Musiolik, Markard, and Hekkert Citation2012; Planko et al. Citation2016), less is known about the interplay between different network actors and their activities when sustainable markets are being shaped (Baker, Storbacka, and Brodie Citation2019; Baker and Nenonen Citation2020). Collaboration is especially needed between public and private actors, as the low incentive of private actors to innovate for environmental sustainability requires governmental intervention and regulatory push (Cainelli, De Marchi, and Grandinetti Citation2015), as well as R&D support from universities and other publicly funded research institutions (Ardito, Petruzzelli, and Ghisetti Citation2019). Despite this recognition, there is a lack of research on public-private collaborations in sustainable innovation networks (Melander and Arvidsson Citation2022).

Innovation networks need to be coordinated, which makes it important to bridge and broker between the actors (Howells Citation2006). Literature on sustainable innovations finds this type of intermediation particularly critical, as it can facilitate collaboration and knowledge transfer among the relevant actors, promote the diffusion of sustainable technologies and practices, and enable the emergence of new markets for sustainable products and services (Kivimaa et al. Citation2019; Kivimaa and Kern Citation2016). Although market-shaping literature has investigated the different roles in market-shaping (Flaig and Ottosson Citation2022), to the best of our knowledge, however, the role of intermediaries or intermediation has not been studied from the market-shaping perspective. Moreover, sustainable innovations have been the focus of investigation in a limited number of empirical market-shaping studies (Keränen et al. Citation2023; Ottosson, Magnusson, and Andersson Citation2020). Consequently, more research has been called for in sustainability contexts (Nenonen, Fehrer, and Brodie Citation2021).

By drawing on the market-shaping literature and integrating insights from intermediation in sustainability transitions, our study aims to increase the understanding of public-private innovation networks in market-shaping for sustainable innovation and the role of intermediation in these market-shaping efforts. Our research questions are: What market-shaping activities do public-private innovation network actors undertake to promote the adoption of sustainable innovations? How does intermediation emerge in these market-shaping activities?

These research questions are addressed through a qualitative case study of a public-private innovation network involving university and industry actors. These actors are brought together by a government-funded and university-led innovation network focused on a new technology that enables the utilisation of side-streams produced in metals and mining industries as raw materials for construction materials industry.

This study contributes to the understanding of market-shaping beyond focal business management, by investigating a broader set of network actors. By illuminating the various activities that actors engage in when shaping sustainable markets and the different intermediation mechanisms required, we can form a deeper understanding of how public-private innovation networks contribute to the adoption and diffusion of sustainable innovations.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Market-shaping for sustainable innovations

Transitions literature has investigated widely how new, sustainable technologies can reach markets, and often describes technological sustainability transitions as a change process induced by the interplay between micro-level technological niches (i.e. protected spaces for new technologies to develop) and the meso-level socio-technical regimes (i.e. existing structures, technologies, norms, and regulations), both of which are affected by a broader macro-level landscape (Kemp, Schot, and Hoogma Citation1998; Schot and Geels Citation2008). Despite having made substantial advancements in the understanding of the diffusion of sustainable innovations, the transitions literature has predominantly taken a system perspective on the diffusion process, lacking specific focus on market formation mechanisms (Bergek Citation2019; Köhler et al. Citation2019). Market formation is typically described as a sub-process of transitions, consisting of nursing temporarily protected niche markets and growing and bridging them gradually to mass markets as the technology develops further (Bergek, Jacobsson, and Sandén Citation2008; Dewald and Truffer Citation2011). However, a detailed understanding of the underlying mechanisms or agentic efforts in market formation is missing in transitions literature (Bergek Citation2019).

Market-shaping literature offers an alternative lens to study sustainable innovations and their entry to markets, giving specific focus on the agency of different actors (Ottosson, Magnusson, and Andersson Citation2020). Market-shaping can be defined as the purposive actions of an actor or a network of actors to ‘change market characteristics by re-designing the content of exchange, and/or re-configuring the network of stakeholders involved, and/or re-forming the institutions that govern all stakeholders’ behaviours in the market’ (Nenonen, Storbacka, and Windahl Citation2019, 618). Market-shaping can be positioned within the broader theoretical frame of ‘market innovation’ which is based on a contemporary view of markets as changing and adaptive systems, rather than fixed entities (Sprong et al. Citation2021). This conceptualisation of markets allows market actors to take active agency in creating and transforming market structure and behaviour in iterative and recursive manner (Nenonen, Storbacka, and Windahl Citation2019; Ottosson, Magnusson, and Andersson Citation2020).

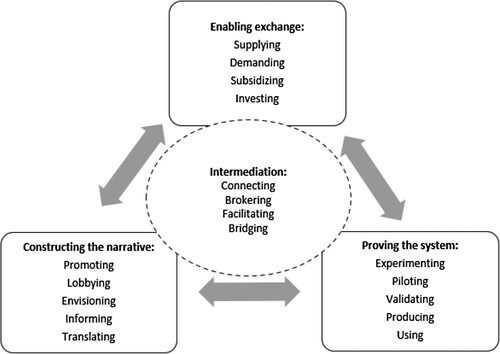

As markets are being shaped through collectively engaging in various activities and interactions with other stakeholders (Baker, Storbacka, and Brodie Citation2019), it is not surprising that market-shaping literature has emphasised the importance of investigating the broad range of activities carried out by different actors to understand market-shaping processes (Kindström, Ottosson, and Carlborg Citation2018; Ottosson, Magnusson, and Andersson Citation2020). On one hand these activities can emphasise operational aspects e.g. individual selling contexts, while other activities address strategic, long-term, and network-oriented issues, e.g. reshaping market norms and business practices within a specific market (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2007; Mele, Pels, and Storbacka Citation2015). By combining research on market-shaping and sustainability transitions Ottosson, Magnusson, and Andersson (Citation2020) suggest a framework that conceptualises market-shaping through three main processes: enabling exchange practices, proving the system, and constructing the narrative. These processes are further divided into specific activities that are carried out by various market actors.

Enabling exchange practices refers to the facilitation of trade and includes all the activities that are related to setting up supply and demand (Ottosson, Magnusson, and Andersson Citation2020). Typically, these exchange practices are lacking and need to be built up from scratch for radical innovations, at the same time as the markets are being formed. Hence, these activities are related to such aspects as pricing, functionality, quality, payment, and delivery (Ottosson and Kindström Citation2016), making business model creation a critical activity for this market-shaping process (Planko et al. Citation2016). While involving actors along the supply chain is necessary for this process to unfold, also governments may be involved in market-shaping. Especially in areas that are considered societally important to develop, governments and policy makers can make interventions to stimulate trade and facilitate exchange through public investments or financial subsidies (Mazzucato and Semieniuk Citation2017).

Proving the system refers to the process of making different kinds of organisational arrangements that enable the production, distribution, and use of the innovation. It includes various activities for experimenting and piloting with technical solutions and validating their functionality and compliance with norms, standards, and requirements (Ottosson, Magnusson, and Andersson Citation2020). However, the technological aspects are only part of this process. The overall intention for these market-shaping efforts is to establish and optimise functioning production and use systems that fulfil specified requirements, standards, and functionality demands (Planko et al. Citation2016).

Constructing the narrative refers to the process consisting of discursive activities that attempt to shape markets through claims that make the innovative technology comprehensible, plausible, and attractive (Ottosson, Magnusson, and Andersson Citation2020). These claims try to state that the innovative technology corresponds to existing system structures, or that structural transformation is required to accommodate the introduction of the new technologies (Raven et al. Citation2016; Smith and Raven Citation2012). Narratives are constructed, for example, through information campaigns, promotion, and lobbying (Ottosson, Magnusson, and Andersson Citation2020), which enable actors to shape the collective expectations and affect the reputation of the new technology in a positive way (Musiolik and Markard Citation2011).

These market-shaping processes and their activities provide an analytical frame to investigate the activities that the public-private innovation network actors of our case study engage in when trying to shape markets for a sustainable innovation. By following the insights of intermediation literature in sustainability transitions context, we aim to develop this framework further by investigating the role of intermediation when these market-shaping processes and activities unfold.

2.2. Intermediation in sustainability transitions

Intermediaries have long been a focus of interest in the fields of innovation studies and science and technology studies. These studies consistently highlight the role of intermediaries in facilitating collaboration and interaction between actors when developing and commercialising innovations (e.g. Howells Citation2006). Intermediaries can help overcome challenges that occur in different stages of the innovation process, such as high transaction costs or communication barriers stemming from divergent interests or varying capacities to absorb and exchange knowledge (Stewart and Hyysalo Citation2008). By bridging these gaps, intermediaries enable the necessary connections and knowledge flows that would otherwise be hindered. Different types of organisations, actors, and even individuals can act as intermediaries and their role can and often does change over time (Kivimaa et al. Citation2019). Indeed, intermediaries can be purposefully established (or ceased) or they can emerge during innovation processes, and sometimes the role is assumed by different actors in an implicit way, as a part of other innovation related activities (Howells Citation2006; Kivimaa et al. Citation2019).

Intermediation has recently gained more attention in sustainability transition studies. These studies recognise that intermediaries can drive transition processes by linking various actors, including both new entrants and incumbents, and their activities and resources, to generate momentum for change (Kivimaa Citation2014; Matschoss and Heiskanen Citation2018). By creating new connections and collaborations around sustainable innovations, the actors can promote niche technologies and disrupt prevailing socio-technical configurations (Gliedt, Hoicka, and Jackson Citation2018; Matschoss and Heiskanen Citation2018).

As the transformation of socio-technical systems is characterised by long-term nature and changes in various levels of analysis (between actors, infrastructures, and technologies and contexts of application) there is an increased need for intermediary action on system or network level (Van Lente et al. Citation2003). Consequently, as opposed to traditional innovation intermediary organisations that often operate in bilateral manner (Howells Citation2006), systemic intermediation is important in the complex sustainability transitions, requiring the coordinated effort of industry, policy makers, research institutes and others (Van Lente et al. Citation2003; Kivimaa Citation2014). Hence, the concept of intermediation is not limited to a specific type of organisation or individual, but rather encompasses a broad range of activities and services that aim to connect and coordinate different actors and can also encompass more abstract and intangible forms of interaction and exchange, such as networks, communities of practice, or open innovation platforms (Gliedt, Hoicka, and Jackson Citation2018).

Although market-shaping literature has investigated the different roles in market-shaping (Flaig and Ottosson Citation2022), the role of intermediaries or intermediation has not been studied from the market-shaping perspective. By combining the market-shaping processes literature and the recent insights about intermediation in sustainability transitions, we propose that intermediation needs to be included as an integral process that enables market-shaping to take place. describes our theoretical framework with market-shaping processes, their related activities, and the central role of intermediation.

3. Methodology

The qualitative case study research design (Yin Citation2003) was chosen to create a deep understanding and rich description (Dyer and Wilkins Citation1991) about the network actors’ activities in shaping markets. The complexity and context-specificity of the research setting and the network characteristics of the phenomenon warrant the use of a single case study approach (Easton Citation1995). Also, the abductive research design that was followed benefits from this flexibility of qualitative case studies. Abductive logic is characterised by an iterative process where the researcher moves repeatedly between empirical findings and theoretical knowledge throughout the research (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002).

3.1. Case context

The case study focuses on a public-private innovation network involving university and industry actors that have been developing sustainable innovations in the field of material sciences with geopolymer technology. This technology enables novel ways to process different industrial side-streams (e.g. blast-furnace slags from steel production, fly ash from coal combustion, mine tailings, and construction waste) so that they can be reused in other industries in place of virgin raw materials. In particular, we are focusing on the development and implementation of geopolymer cement that can be used as an ingredient for more environmentally friendly concrete.

This case study provides a suitable context for analysing market-shaping in a network with university and industry actors from steel, mining, and minerals industries that are conservative and highly polluting, and currently in the midst of sustainability transition. The complexity of turning operations from linear to circular and the science-based nature of sustainable materials innovation further underscore the need to involve actors from a variety of industries and sectors. In addition, the case study was conducted in Finland, a country that has quite recently made exceptionally ambitious goals for circular economy and climate change mitigation on the national level, which obliges also industry actors to take on greater responsibility (Finnish Ministry of the Environment Citation2021).

3.2. Data collection and analysis

The primary empirical data includes 16 thematic interviews. The data gathering started by interviewing university researchers (5) and industry actors (6) that were directly involved in the government-funded innovation project. The industry actors included both side-stream producers (2) and side-stream users (3), and a university spin-off company (1). During the interviews other relevant stakeholders, such as university innovation centre representatives (2), industry association (1), innovation intermediary (1) and regulatory body representatives (1) were identified.

Thematic interviews allowed a flexible way to collect rich data. Interview questions could be emphasised differently depending on the informant making elaborations on emerging issues possible. Nevertheless, all the interviews addressed the same themes: origins of the innovation, the challenges related to, and the activities needed for its development and commercialisation, and perceived roles in the innovation’s wider upscaling.

The interviews were conducted between January-December 2021, each interview lasting between 50–90 min. The interview data was supplemented by secondary data from various sources: webinars (both research and industry oriented), reports and news regarding the involved industries, and web pages of the industrial partners and relevant industry associations. This data was gathered to increase researchers’ understanding about the industry and to triangulate the findings of the interviews collected (Yin Citation2003), but was excluded from the actual data analysis.

The interview data was analysed using content analysis and coding procedure including the phases of data reduction, data display and drawing conclusions (Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña Citation2014). As typical for abductive research process, also the coding was iterative, including two rounds of coding. First, more open coding was conducted that took place simultaneously with data gathering. Towards the end of the interviews the proliferation of emerging codes slowed down, indicating data saturation. During the second round of coding, the focus was fixed on market-shaping activities as the main theme and intermediation as an emergent aspect supporting these market-shaping activities.

4. Case analysis

4.1. Side-stream producers’ market-shaping activities

The side-stream producers are representing two different companies from steel production and mining and minerals industry. Both companies engage in this innovation network mainly for two reasons. Firstly, harvesting the remaining valuable minerals from the side-streams is a significant business opportunity. Secondly, the side-stream producers are responsible for landfilling vast volumes of process waste, which is a big cost and a huge environmental burden. Despite these opportunities side-streams are still quite marginal, and the strategic focus is on the core processes and core products. For example, the other side-stream producer has engaged in various internal investigations to find ways to make side-streams more suitable for reuse purposes, but the investments that would be needed cannot be justified with current mineral prices.

Although there is some pressure to minimise waste and side-streams, the most critical issue for both side-stream producers is currently the reduction of CO2 emissions in their production. They see that the situation will not change unless there will be more stringent regulations and higher taxes on landfilling. There are already some signs towards this direction, as circular economy and waste minimisation are gaining more foothold alongside climate change mitigations measures. Hence, one big motivation for side-stream producers to be part of this innovation network is to be on top of matters when waste management regulations will be changed. However, they see themselves mainly as material producers in this network and perceive university to be responsible for coming up with new applications for processing waste materials. Their own R&D functions are relatively small and mainly concentrated on process technologies for the core products. Consequently, the university is an important partner for the side-stream producers. Nevertheless, both companies have a long history and they have accumulated a lot of knowledge around side-streams through their own investigations. This knowledge is seen as one of their biggest contributions to the innovation network, and hence to the proving of the system with regard to market shaping.

If we gather all the studies that we have done related to the utilization of slags [type of side-stream], then there is really a great deal done. We have a really long history with those. (R&D Director, side-stream producer B)

However, both organisations see that the market for geopolymer concrete is not in their direct interest. They see their role very limited in the enabling of exchange – they feel that there should be some third-party operator in between who is responsible for processing the materials further for customers. Hence, they are assuming more a supporter’s role in the market-shaping processes.

If one thinks about investments related to by-products, they compete with the investments related to the main product itself. — We have no interest to produce any end-products as such, but instead we can supply the raw material to the customer, who then carries out the necessary processing and finally places the product on the market. (R&D Manager, side-stream producer A)

4.2. Side-stream users’ market-shaping activities

The side-stream users operate in the construction materials industry representing a multinational corporation (parent company with two subsidiaries). The side-stream users have a strong commitment to sustainability, which is strongly embedded in the corporate strategy. Carbon neutrality is a top priority in their sustainability roadmap, and thus, the use of low-carbon alternatives for cement is of key importance. However, being such a big corporation with vast array of different construction materials, cementitious materials represent only one fraction of their offerings. Thus, although the geopolymer technology holds significant potential for the company, it is only one part of the whole sustainability effort.

We are a forerunner. And we are unique as a company, because we have a wide assortment of different products for the construction, and we are such a big player that it's actually our responsibility to take the lead and to progress the whole industry. (Sustainability Manager, parent company)

I think for some applications it [technology] is good to go. From a product point of view. But then you have the whole supply chain build up. — And in different countries you have quite similar certificates or regulations. And even if they are not legislated or officially regulated, you need to follow it because the market is demanding certain behaviour. (R&D Director, subsidiary A)

The side-stream users see that the new material development is primarily the university’s job, and the subsequent new product development is primarily an internal endeavour. Although the side-stream users have a central role in proving the system through their own pilots and product development, they perceive the network actors’ roles somewhat separate.

We do more applications and business applications, product development out of the knowledge generated at the university. Our task is in the end to commercialize this. If the university is providing knowledge, we are providing them the applications. (R&D Director, subsidiary B)

4.3. University’s and university spin-off’s market-shaping activities

The university can be seen as an integral connector between the side-stream producers and users. The research around geopolymer technology started at the university about 10 years ago, and the researchers have built an extensive collaboration network with many companies and research institutions. The researchers estimate that they have been collaborating with around 40–50 companies with different emphasis and application areas. The university researchers see their role as an important research partner, helping companies to become more sustainable. Thus, technical experimentation and validation activities have been critical and recurrent, contributing to the proving of the system.

We also see our role in the ecosystem as being the sort of research partner, because many of the companies nowadays don't have their own research labs or research personnel and so that's been changing the past 5–10 years, they have reduced in size quite a bit. (University researcher A)

The companies’ reluctance to implement the technology in practice has inspired one of the university researchers to establish a spin-off company that can offer pilot testing capabilities between lab-scale and factory-scale, which was previously a big obstacle. The spin-off company thus plays a significant role in proving the system and enabling exchange between side-stream producers and users.

4.4. Intermediation for market-shaping activities

Intermediation emerges in the public-private innovation network as a result of the complex collaborations among the network actors involved in driving the sustainable innovation. First, intermediation contributes to enabling exchange by brokering buyers and sellers. This connecting and matchmaking of side-stream producers and users is critical for the creation of transactional infrastructure and a safe space to experiment with different business models. The innovation network also reduces information asymmetry by providing valuable information about products, regulations, prices, and market conditions, both in the side-stream production and application sides. Secondly, the innovation network provides significant contribution to proving the system by collaboratively configuring the technological solution so that it can be accepted by the markets. This configuration involves not only connecting expertise and technical knowledge to analyse the viability and sustainability of technologies, but also certifying technologies against specific standards. As this requires changes in the normative environment, for highly regulated construction products, also wider stakeholder engagement is needed, further adding to the potential intermediation that the focal network can offer. Finally, intermediation supports narrative construction by facilitating the communication efforts that try to highlight the benefits of the new technology and materials. This type of facilitation is needed also internally in the network, as the actors have varying perspectives about the technology and its strategic importance. In addition, by engaging diverse stakeholders in the narrative construction process, the innovation network can facilitate dialogues and collaborative initiatives that involve not only innovators, but also policymakers, other businesses, and NGOs, that can further advocate the uptake of the innovation.

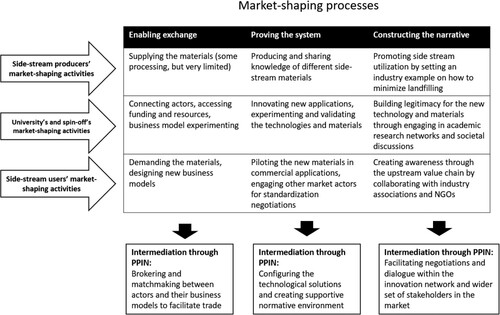

below illustrates the different activities that the network actors are performing and how intermediation is emerging through the network collaborations.

5. Discussion

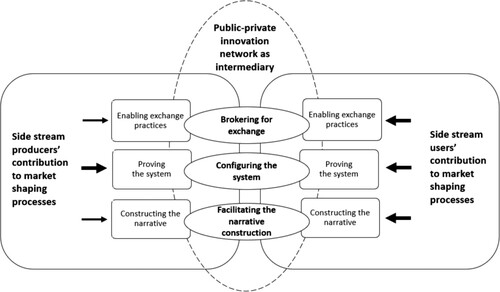

By building on the framework of market-shaping processes and related activities by Ottosson, Magnusson, and Andersson (Citation2020) the study has shown how the different public-private innovation network actors are contributing to the market-shaping activities for a sustainable innovation. Furthermore, by focusing on the intermediation that the network can provide, this study provides new understanding of the essential intermediary mechanisms necessary for market-shaping. This study has two key contributions that are illustrated in and explained below in more detail.

Figure 3. Market-shaping processes in side-stream production and utilisation industries mediated by the public-private innovation network. The width of the arrow indicates the level of influence.

First, we have identified the strong interdependence of market-shaping activities conducted between side-stream producing and using industries. Both sides perform various interrelated activities which are contributing to the market-shaping with different level of influence (indicated by the width of the arrow in the figure). However, these activities have a complementary and collective nature, meaning that the contribution of actors on both sides is needed for enabling exchange, proving the system and constructing the narrative. Hence, our findings align with the idea that market-shaping involves the active participation and engagement of various actors that can be either active market shapers or more reactive market supporters (Flaig and Ottosson Citation2022; Nenonen and Storbacka Citation2020). While side-stream users as active market shapers play a more direct role in influencing and shaping the market, side-stream producers support market creation in a more subtle way by providing backing, advocacy, and resources (e.g. materials and knowledge). However, the side-stream producers anticipate the situation to change as regulation moves towards more stringent approach to waste management, requiring that they change their strategic focus in the future. This finding supports the notion that shaping sustainable markets is a dynamic process where the roles of different actors tend to change during time (Flaig and Ottosson Citation2022; Ottosson, Magnusson, and Andersson Citation2020).

The second contribution relates to uncovering the intermediation mechanisms related to these market-shaping processes. Although some market-shaping literature (e.g. Nenonen and Storbacka Citation2020) points to the importance of market shapers to orchestrate and lead the market-shaping in a coordinated way, in our case study the market-shaping efforts appear to take place in a less organised way. While a clear orchestrator or lead actor can bring focus and coordination to market-shaping efforts, the absence of such a role does not necessarily hinder market-shaping. In fact, a less organised approach may foster more creativity, flexibility, and adaptability, allowing for diverse experimentations, solutions, and dynamic market development. Indeed, our findings indicate the integral role of the public-private innovation network as an intermediary that facilitates these market-shaping processes in the absence of a central lead actor. Firstly, through brokering for exchange, the network can connect side-stream producing and using side and provide opportunities to create transactional infrastructure, which is currently lacking certain actors (i.e. material processors) and activities (i.e. logistics). Secondly, through configuring the system the network can contribute the optimisation and further development of the technological system (the innovation), but also to the surrounding system, entailing normative aspects through standardisation and legitimisation, that further drive the adoption and use of these new materials. Thirdly, the innovation network can facilitate the narrative construction by influencing the discourse, perceptions, and understanding of the sustainable innovation’s benefits and potential. They can mobilise especially financial support and inspire action that will enable even wider set of stakeholders beyond the innovation network to engage in further market-shaping and create a shared vision of a more sustainable future.

6. Conclusions

Sustainable innovations and intermediation have been studied extensively in sustainability transitions literature through a system-level perspective (Markard, Geels, and Raven Citation2020; Schot and Geels Citation2008), but so far, they have received very limited attention in the market-shaping literature that gives special emphasis on the agency of various actors (Nenonen, Storbacka, and Windahl Citation2019; Nenonen and Storbacka Citation2020). In addition, market-shaping has paid limited attention to the networked and collective efforts when shaping markets (Baker, Storbacka, and Brodie Citation2019). In particular, public-private innovation networks have been an under-researched focus of studies, although their significance for sustainable innovations is widely recognised (Doganova and Karnøe Citation2015; Melander and Arvidsson Citation2022). This study has shed light to these topics by investigating the special, agentic role that public-private innovation networks can play in market-shaping between different industry sectors. Through a qualitative case study, this paper has explored the market-shaping activities in a public-private innovation network focused on side-stream utilisation technology, highlighting the role of public-private networks as intermediaries in market-shaping.

Our study shows that the activities of different network actors are highly complementary and collective, although they are not centrally coordinated by any central lead actor. In addition, the study identified public-private innovation networks as important intermediary spaces that contribute to the collective action and the advancement of sustainable innovations, even in the absence of a centralised leadership role. They act as important catalysts for market-shaping by brokering for exchange, configuring the system, and facilitating narrative construction.

6.1. Theoretical implications

This study has implications for the research on market-shaping and intermediation in sustainability transitions. First, our study complements previous studies on market-shaping activities (Kindström, Ottosson, and Carlborg Citation2018; Ottosson, Magnusson, and Andersson Citation2020), by demonstrating how the varying activities of different network actors collectively contribute to market-shaping and how intermediation offered by the network can facilitate the interplay of these activities. Hence, the findings of our study contribute to a deeper understanding of the collective agency and the inherent complexity of managing these collective market-shaping efforts (Baker and Nenonen Citation2020). Moreover, our study provides new insights by identifying intermediation as a critical market-shaping mechanism. As the success of sustainable innovation’s implementation is dependent on various actors’ collaborative effort, there is a need to find ways to coordinate and align market-shaping activities across actors and industries. Thus, understanding intermediation as an integral part of market-shaping is important for the development and adoption of sustainable innovations and for the sustainability transitions in general.

Second, our study offers new insights to intermediation in sustainability transitions (Gliedt, Hoicka, and Jackson Citation2018; Kivimaa et al. Citation2019). It describes the importance of networks as intermediary spaces, catalysing the sustainability transitions across industries with the help of various public and private actors. In this way, our study complements previous studies on intermediation that have taken organisations or individuals as their primary focus (Kivimaa et al. Citation2019: Van Lente et al. Citation2003). By exploring a network as an intermediary, this study contributes to the richer understanding of different forms of intermediation.

6.2. Managerial and policy implications

The findings highlight the need for practitioners and policymakers to recognise the significance of collective market-shaping and the required intermediation in driving these collective market-shaping efforts for sustainable innovations. By understanding the interplay of activities between different actors and industries, stakeholders can strategically leverage intermediation to overcome barriers, build partnerships, and navigate the complex landscape of market-shaping.

For managers in particular, our findings suggest that firms need to broaden their strategic focus beyond their own industry and understand market-shaping activities in a wider context, especially in case of sustainable innovations that have systemic features. Moreover, in conservative industries characterised by long, established value chains, and high dependency on policy and regulatory bodies, the role of coordinated and collective market-shaping is highlighted.

As for policy makers the study highlights the importance of fostering an environment that supports the formation and operation of public-private innovation networks. The key for sustainable innovation lies in interactions, collaborations, and learning between various public and private actors. Understanding the complexities and the specific need for intermediation is critical for policy makers to make well-informed decisions on programmes that support, finance, and oversee sustainable innovations and the complex collaborations that they involve.

6.3. Limitations and further research directions

Although our research is based on a single case study in one country, the findings can offer valuable insight in other similar settings where sustainable innovation spans across stable and mature industries and involves various actors both from private and public sectors. Our case study has examined market-shaping in the context of a specific innovation (geopolymer) meant for a specific application (construction, replacing concrete). Further studies could look broader into the different sustainable materials in construction or other application areas for geopolymers and the wider network of relevant actors to uncover broader layers of sustainability effects (see e.g. Keränen et al. Citation2023). We acknowledge that local policies and legislation influence the nature and type of market-shaping activities that public-private innovation network actors engage in, and therefore further studies in different geographical contexts with same or similar innovation area could be beneficial in broadening the understanding even further. Moreover, longitudinal studies can be especially helpful in capturing the dynamic nature of market-shaping for sustainable innovation and its long-term implications.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which significantly enhanced the quality of our paper. Furthermore, we would like to express our gratitude to the interviewees for their invaluable contribution by dedicating their time and effort to participate in this research. We would also like to acknowledge the University of Oulu and the Academy of Finland (InStreams Profi5, 326291) for their support in conducting this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mari Mehtälä

Mari Mehtälä is a Doctoral Researcher at Oulu Business School, University of Oulu, Finland. She holds a M.Sc. Degree in Marketing, and her research interests include sustainable innovations, innovation networks, and commercialisation.

Tuula Lehtimäki

Dr Tuula Lehtimäki is a Post-doctoral Researcher at Oulu Business School, University of Oulu, Finland. Her major research interests are commercialisation of innovations, business relationships and sustainable innovation. She has published, for example, in Industrial Marketing Management.

Hanna Komulainen

Dr Hanna Komulainen is an Associate Professor at Oulu Business School, University of Oulu, Finland. She obtained her PhD in marketing from University of Oulu in 2010. Her research interests include B2B relationships, sustainable business, service experience and value co-creation in emergent service contexts, e.g. health-care, financial and mobile services. She has published, among others, in Industrial Marketing Management, Journal of Service Management, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, Management Decision, Marketing Intelligence and Planning and Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing.

References

- Adams, R., S. Jeanrenaud, J. Bessant, D. Denyer, and P. Overy. 2016. “Sustainability-oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Management Reviews 18 (2): 180–205. doi:10.1111/ijmr.12068.

- Ardito, L., A. M. Petruzzelli, and C. Ghisetti. 2019. “The Impact of Public Research on the Technological Development of Industry in the Green Energy Field.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 144: 25–35. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2019.04.007.

- Baker, J. J., and S. Nenonen. 2020. “Collaborating to Shape Markets: Emergent Collective Market Work.” Industrial Marketing Management 85: 240–253. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.11.011.

- Baker, J. J., K. Storbacka, and R. J. Brodie. 2019. “Markets Changing, Changing Markets: Institutional Work as Market Shaping.” Marketing Theory 19 (3): 301–328. doi:10.1177/1470593118809799.

- Bergek, A. 2019. “Technological Innovation Systems: A Review of Recent Findings and Suggestions for Future Research.” Handbook of Sustainable Innovation, 200–218. doi:10.4337/9781788112574.00019.

- Bergek, A., S. Jacobsson, and B. A. Sandén. 2008. “Legitimation’and ‘Development of Positive Externalities’: Two Key Processes in the Formation Phase of Technological Innovation Systems.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 20 (5): 575–592. doi:10.1080/09537320802292768.

- Cainelli, G., V. De Marchi, and R. Grandinetti. 2015. “Does the Development of Environmental Innovation Require Different Resources? Evidence from Spanish Manufacturing Firms.” Journal of Cleaner Production 94: 211–220. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.008.

- Cillo, V., A. M. Petruzzelli, L. Ardito, and M. Del Giudice. 2019. “Understanding Sustainable Innovation: A Systematic Literature Review.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26 (5): 1012–1025. doi:10.1002/csr.1783.

- De Marchi, V. 2012. “Environmental Innovation and R&D Cooperation: Empirical Evidence from Spanish Manufacturing Firms.” Research Policy 41 (3): 614–623. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.10.002.

- Dewald, U., and B. Truffer. 2011. “Market Formation in Technological Innovation Systems—Diffusion of Photovoltaic Applications in Germany.” Industry & Innovation 18 (3): 285–300. doi:10.1080/13662716.2011.561028.

- Doganova, L., and P. Karnøe. 2015. “Building Markets for Clean Technologies: Controversies, Environmental Concerns and Economic Worth.” Industrial Marketing Management 44: 22–31. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.10.004.

- Dubois, A., and L.-E. Gadde. 2002. “Systematic Combining: An Abductive Approach to Case Research.” Journal of Business Research 55 (7): 553–560. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8.

- Dyer, W. G. J., and A. L. Wilkins. 1991. “Better Stories, not Better Constructs, to Generate Better Theory: A Rejoinder to Eisenhardt.” The Academy of Management Review 16 (3): 613–619. doi:10.2307/258920.

- Easton, G. 1995. “Methodology and Industrial Networks.” In K. Möller & D. Wilson (Eds.). Business Marketing: An Interaction and Network Perspective (pp. 411–492). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers Group.

- Finnish Ministry of the Environment. 2021. “Government Resolution on the Strategic Programme for Circular Economy.” https://ym.fi/documents/1410903/42733297/Government+resolution+on+the+Strategic+Programme+for+Circular+Economy+8.4.2021.pdf/309aa929-a36f-d565-99f8-fa565050e22e/Government+resolution+on+the+Strategic+Programme+for+Circular+Economy+8.4.2021.pdf?t=1619432219261.

- Flaig, A., and M. Ottosson. 2022. “Market-shaping Roles – Exploring Actor Roles in the Shaping of the Swedish Market for Liquefied gas.” Industrial Marketing Management 104: 68–84. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2022.04.006.

- Geels, F. W. 2002. “Technological Transitions as Evolutionary Reconfiguration Processes: A Multi-Level Perspective and a Case-Study.” Research Policy 31 (8–9): 1257–1274. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00062-8.

- Geels, F. W., M. P. Hekkert, and S. Jacobsson. 2008. “The Dynamics of Sustainable Innovation Journeys.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 20 (5): 521–536. doi:10.1080/09537320802292982.

- Gliedt, T., C. E. Hoicka, and N. Jackson. 2018. “Innovation Intermediaries Accelerating Environmental Sustainability Transitions.” Journal of Cleaner Production 174: 1247–1261. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.054.

- Hall, J., and M. Wagner. 2012. “Integrating Sustainability Into Firms’ Processes: Performance Effects and the Moderating Role of Business Models and Innovation.” Business Strategy and the Environment 21 (3): 183–196. doi:10.1002/bse.728.

- Howells, J. 2006. “Intermediation and the Role of Intermediaries in Innovation.” Research Policy 35 (5): 715–728. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2006.03.005.

- Kemp, R., J. Schot, and R. Hoogma. 1998. “Regime Shifts to Sustainability Through Processes of Niche Formation: The Approach of Strategic Niche Management.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 10 (2): 175–198. doi:10.1080/09537329808524310.

- Keränen, O., T. Lehtimäki, H. Komulainen, and P. Ulkuniemi. 2023. “Changing the Market for a Sustainable Innovation.” Industrial Marketing Management 108: 108–121. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2022.11.005.

- Kindström, D., M. Ottosson, and P. Carlborg. 2018. “Unraveling Firm-Level Activities for Shaping Markets.” Industrial Marketing Management 68: 36–45. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.09.003.

- Kivimaa, P. 2014. “Government-affiliated Intermediary Organisations as Actors in System-Level Transitions.” Research Policy 43 (8): 1370–1380. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2014.02.007.

- Kivimaa, P., W. Boon, S. Hyysalo, and L. Klerkx. 2019. “Towards a Typology of Intermediaries in Sustainability Transitions: A Systematic Review and a Research Agenda.” Research Policy 48 (4): 1062–1075. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.10.006.

- Kivimaa, P., and F. Kern. 2016. “Creative Destruction or Mere Niche Support? Innovation Policy Mixes for Sustainability Transitions.” Research Policy 45 (1): 205–217. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2015.09.008.

- Kjellberg, H., and C.-F. Helgesson. 2007. “On the Nature of Markets and Their Practices.” Marketing Theory 7 (2): 137–162. doi:10.1177/1470593107076862.

- Köhler, J., F. W. Geels, F. Kern, J. Markard, E. Onsongo, A. Wieczorek, F. Alkemade, … et al. 2019. “An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of the art and Future Directions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31: 1–32. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004.

- Markard, J., F. W. Geels, and R. Raven. 2020. “Challenges in the Acceleration of Sustainability Transitions.” Environmental Research Letters 15 (8): 0081001. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab9468.

- Matschoss, K., and E. Heiskanen. 2018. “Innovation Intermediary Challenging the Energy Incumbent: Enactment of Local Socio-Technical Transition Pathways by Destabilisation of Regime Rules.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 30 (12): 1455–1469. doi:10.1080/09537325.2018.1473853.

- Mazzucato, M., and G. Semieniuk. 2017. “Public Financing of Innovation: New Questions.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 33 (1): 24–48. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grw036.

- Melander, L., and A. Arvidsson. 2022. “Green Innovation Networks: A Research Agenda.” Journal of Cleaner Production 357: 131926. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131926.

- Mele, C., J. Pels, and K. Storbacka. 2015. “A Holistic Market Conceptualization.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43 (1): 100–114. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0383-8.

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis : A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage. https://oula.finna.fi/Record/oy.9913813313906252

- Musiolik, J., and J. Markard. 2011. “Creating and Shaping Innovation Systems: Formal Networks in the Innovation System for Stationary Fuel Cells in Germany.” Energy Policy 39 (4): 1909–1922. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.12.052.

- Musiolik, J., J. Markard, and M. Hekkert. 2012. “Networks and Network Resources in Technological Innovation Systems: Towards a Conceptual Framework for System Building.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 79 (6): 1032–1048. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2012.01.003.

- Nenonen, S., J. Fehrer, and R. J. Brodie. 2021. “Editorial: Jbr Special Issue on Market Shaping and Innovation.” Journal of Business Research 124: 236–239. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.062.

- Nenonen, S., and K. Storbacka. 2020. “Don’t Adapt, Shape! Use the Crisis to Shape Your Minimum Viable System – And the Wider Market.” Industrial Marketing Management 88: 265–271. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.05.022.

- Nenonen, S., K. Storbacka, and C. Windahl. 2019. “Capabilities for Market-Shaping: Triggering and Facilitating Increased Value Creation.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 47 (4): 617–639. doi:10.1007/s11747-019-00643-z.

- Ottosson, M., and D. Kindström. 2016. “Exploring Proactive Niche Market Strategies in the Steel Industry: Activities and Implications.” Industrial Marketing Management 55: 119–130. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.08.003.

- Ottosson, M., T. Magnusson, and H. Andersson. 2020. “Shaping Sustainable Markets—A Conceptual Framework Illustrated by the Case of Biogas in Sweden.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 36: 303–320. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.10.008.

- Planko, J., J. M. Cramer, M. M. H. Chappin, and M. P. Hekkert. 2016. “Strategic Collective System Building to Commercialize Sustainability Innovations.” Journal of Cleaner Production 112 (Part 4): 2328–2341. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.108.

- Raven, R., F. Kern, B. Verhees, and A. Smith. 2016. “Niche Construction and Empowerment Through Socio-Political Work. A Meta-Analysis of six low-Carbon Technology Cases.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 18: 164–180. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2015.02.002.

- Schot, J., and F. W. Geels. 2008. “Strategic Niche Management and Sustainable Innovation Journeys: Theory, Findings, Research Agenda, and Policy.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 20 (5): 537–554. doi:10.1080/09537320802292651.

- Smith, A., and R. Raven. 2012. “What is Protective Space? Reconsidering Niches in Transitions to Sustainability.” Research Policy 41 (6): 1025–1036. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.12.012.

- Sprong, N., P. H. Driessen, B. Hillebrand, and S. Molner. 2021. “Market Innovation: A Literature Review and new Research Directions.” Journal of Business Research 123: 450–462. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.057.

- Stewart, J., and S. Hyysalo. 2008. “Intermediaries, Users and Social Learning in Technological Innovation.” International Journal of Innovation Management 12 (03): 295–325. doi:10.1142/S1363919608002035.

- Van Lente, H., M. Hekkert, R. Smits, and B. A. S. Van Waveren. 2003. “Roles of Systemic Intermediaries in Transition Processes.” International Journal of Innovation Management 07 (03): 247–279. doi:10.1142/S1363919603000817.

- Yin, R. K. 2003. Applications of Case Study Research. In Applied Social Research Methods Series. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.