ABSTRACT

SMEs have a significant impact on the economies of developing countries. Thus it is crucial to understand how they can improve their performance. This study explores the relationship between innovation capabilities, innovation strategy and financial performance in a sample of 136 SMEs from Valle del Cauca – Colombia. We use a structural equation model to analyse how this relationship could inform the management of innovation in SMEs. This study demonstrated positive relationships between innovation capabilities and innovation strategy, as well as between these two variables and financial performance. The results indicate that not all strategies generate good performance and although cooperation is one of the best performing strategies, other findings are discussed in the study.

Introduction

In developing countries, where most companies are small, the literature shows the contribution of SMEs to competitiveness, but studies regarding the activities carried out by these companies to innovate are very limited (Hair et al. Citation2021). Situation that limits knowledge regarding the barriers companies must face, and how they develop innovation processes, improve their capabilities to innovate, and contribute to economic growth (Hervas-Oliver, Boronat-Moll, and Sempere-Ripoll Citation2016). From the point of view of the innovation strategies used by the company and the innovation capabilities it has, it is important to ask: What relationship can be observed between innovation strategies, innovation capabilities and financial performance in SMEs? Answering this question provides an empirical basis for understanding how companies create value, moving from efficiency to effectiveness (Teece Citation2018).

According to Teece (Citation2017), the capabilities theory makes it easier to understand how the company manages the resources to compete, grow and innovate. It provides a useful framework for decision-making for the allocation and management of resources, and the generation of competitive advantages, since companies differ mainly in their abilities to decide, innovate and change. Despite the importance of innovation capabilities on innovation results and performance (Barbosa Ferreira, Coelho, and Weersma Citation2018; Teece Citation2017), advances in innovation and innovation capabilities according to the results of the global innovation index (Cornell University et al. Citation2019) and the competitiveness report (Schwab Citation2019) in Latin American countries in general and in Colombia in particular continue to show lags with respect to developed countries.

This research proposes to contribute to the construction of an explanatory framework for innovation management of SMEs in developing countries, analysing the relationship between innovation strategies, innovation capabilities and financial performance, from an empirical validation with a group of 136 SMEs from Valle del Cauca – Colombia, region that is characterised by having an important business dynamics of SMEs (98%). This establishes a baseline of useful knowledge for decision-making regarding business competitiveness based on innovation.

Innovation capabilities

Innovation capabilities are related to the capability of the organisation to initiate, develop and achieve innovation results using the set of technological and organisational skills (OCDE & Eurostat Citation2018, 104). They are one of the pillars that are required to improve the competitiveness of both countries and companies (World Economic Forum Citation2018).

Innovation capabilities are considered a special asset of a company. They are an important source of competitiveness to the extent that their exploitation enables the introduction of new products and the adoption of new processes. However, given the complexity to generate innovation, the company needs a variety of assets, resources and capabilities that enables it to execute the strategy and adapt to the conditions of the competitive environment (Guan and Ma Citation2003).

The innovation capabilities of a company are explained from different dimensions (Guan and Ma Citation2003; Yam et al. Citation2004, Citation2010, Citation2011): (a) learning capability, includes the capability to identify, assimilate and exploit the new knowledge essential for the competitive success; (b) R&D capability helps embrace many new technologies and approaches when developing new technology assets; (c) capability to take advantage of resources represents the company's capability to mobilise and expand its technological, human and financial resources; (d) manufacturing capability transforms R&D results into products that meet market needs; (e) marketing capability implies advertising and selling the products based on the understanding of the current and future needs of the consumers, the access approaches of the clients and the knowledge of the competitors; (f) organisational capability to constitute a well-established structure, coordinate the work of all activities towards shared objectives and influence the speed of innovation processes; (g) strategic capability allows adopting different types of strategies that can adapt to changes in the environment to stand out in the highly competitive environment.

Innovation strategies

According to the key success factors that the company possesses, it chooses its strategies to innovate and achieve a competitive position in the market. Thus a strategy based on R&D activities can generate technological leadership through new products or technologies. Those companies that imitate, offering the leader's products with some improvements, are called ‘followers’. They can also choose to acquire knowledge and technology from market leaders.

Taking into account the limited information available on SMEs in developing countries such as Colombia, as well as the difficulties in clearly identifying their strategies, and that the prevailing approach in the literature is related to internal organisational processes, the present study it will take as a basis to identify innovation strategies, the proposal made by Bo and Qiuyan (Citation2012) from four perspectives: (a) R&D; (b) cooperation; (c) imitation and (d) acquisition.

Innovation strategy by acquisition

Acquisition is an option chosen by companies to access a greater set of knowledge than is available internally, leveraging the growing costs of technological development and the high rate of depreciation of new products on the market (Mata and Woerter Citation2013). It can occur through mergers and acquisitions (Dunlap et al. Citation2016), purchase of external technology (Cammarano, Michelino, and Caputo Citation2019), outsourcing of R&D activities and acquisition of knowledge, machinery and equipment, although with a low impact on generation of new products (Grabowski and Staszewska-Bystrova Citation2020).

The acquisition expands the company's knowledge base, compensates for its weaknesses and enhances organisational learning, increasing the probability of success of new products. By interacting with the external context, access to new technologies and specialised talent is facilitated, increasing dynamic capabilities (Mawson and Brown Citation2016). This strategy requires a close integration of internal and external knowledge to capture the positive effects of innovative activity, combining innovation activities to create an adequate context to generate innovation and therefore a sustainable competitive advantage (Valentini and Di Guardo Citation2012; Wang, Xiao, and Savin Citation2021).

In summary, the acquisition strategy can occur through five types of activities: purchase of external technology, mergers and acquisitions, outsourcing of R&D activities, knowledge acquisition and licensing.

Innovation by imitation strategy

Innovation by imitation is a form of technological development that expands knowledge within the company by developing products based on an existing product in the market. In uncertain environments, it is very attractive to generate new products that are already being validated by the market to reduce uncertainty, so it is a strategy that is related to incremental innovation rather than radical innovation (Wu et al. Citation2020) and it occurs mainly in smaller companies that may have positive effects on performance.

This strategy is efficient in sectors with medium technological intensity in which the company seeks to improve products to introduce them in new markets (Oh, Cho, and Kim Citation2015); It also makes it easier for technologically lagging companies to overcome the barriers of technical, technological and human resources, allowing them to acquire basic skills to identify and evaluate technologies, acquire knowledge and improve operational and innovative capacity (Liu, Wei, and Li Citation2019). It is focused on exploitative learning given the ability generated by the company to reuse and make the most of existing and available knowledge in the company (Ali Citation2021).

Compared to performance, this strategy entails lower costs than R&D, reduces uncertainty (Wu et al. Citation2019) and can generate high profits and even outperform the competition when combined with other strategies (Wu et al. Citation2020). However, in the medium term it can slow down business growth, since it tends to discourage investment in R&D activities for the differential products.

Contrary to this approach, Wu et al. (Citation2020) and Afshar Jahanshahi and Brem (Citation2020) state that although this strategy favours growth, it triggers more ruthless competition, which leads companies to invest more resources in R&D to differentiate themselves from imitators. Additionally, Wu et al. (Citation2019) state that when companies are more inclined towards imitation, they can miss out on their creative capabilities and miss out on opportunities for radical innovation, since the company tends to focus on taking advantage of its existing capabilities.

Cooperation innovation strategy

This strategy is mainly used in small companies with low technological intensity and limited R&D activities (Barge-Gil Citation2009; de Resende et al. Citation2018; Devece, Ribeiro-Soriano, and Palacios-Marqués Citation2019), which seek to take advantage of accessing and sharing strategic resources, thus overcoming common limitations and knowledge and investment demands (de Resende et al. Citation2018; Velázquez Castro, Cruz Coria, and Vargas Martínez Citation2018) to generate innovation through participation with various agents in the national context, thus improving performance, efficiency (Klimas and Czakon Citation2018) and competitiveness (Kraus et al. Citation2018).

The types of cooperating partners are: clients, suppliers, competitors, non-competitors, companies of the same business group, universities and research centres (Barge-Gil Citation2009; Weber and Heidenreich Citation2018). However, cooperation between competitors may generate greater risks of knowledge leakage (Bouncken and Kraus Citation2013).

Cooperation performance is determined by the exchange of knowledge, learning (Xie et al. Citation2020), the technological uncertainty of the context, as well as the ability to generate synergies and complement resources (Rehm and Goel Citation2017). The limitations are related to the protection of knowledge (Barge-Gil Citation2009; Bouncken and Kraus Citation2013), managerial difficulties in managing relationships with external partners, and scarce human and financial resources (Chun and Mun Citation2011). However, the benefits of cooperation outweigh the risks and costs, to the extent that greater development and product differentiation is generated by the companies that cooperate in R&D activities (Henttonen and Hurmelinna-Laukkanen Citation2014).

R&D innovation strategy

This strategy focuses its efforts on R&D activities, promotes organisational flexibility and the identification of opportunities and trends to anticipate market changes, so it is directly related to competitive advantage and innovation capabilities, to generate new products through exploration (Ali Citation2021).

The R&D strategy involves new technologies, radical changes both in the product and processes as well as in the industry and the market, so it has a direct relationship with the development of new paradigms and trajectories that are potentially exploitable for the company and determine the technological appropriability (Dosi Citation1992) in companies that seek to generate radical innovation, overcoming the limitations of incremental innovation (Richter, Jackson, and Schildhauer Citation2018), improving their performance, even on an SME scale (Ali Citation2021; Gunday et al. Citation2011; Rosenbusch, Brinckmann, and Bausch Citation2011); however, it is difficult to achieve the proposed goals and align it with other strategies in the company (Søndergaard, Knudsen, and Laugesen Citation2021).

Financial performance

The performance of the company is the product of the strategies, resources and capabilities that are configured to respond quickly to changes or even influence the business environment to introduce a new value to the market (Bature et al. Citation2018; Eisenhardt and Martin Citation2000; Teece, Pisano, and Shuen Citation1997). Consequently, organisational capacity influences the performance of SMEs in the market. However, there is still no clear consensus about the benefits of innovation strategies, especially related to SMEs (Zuñiga-Collazos et al. Citation2020), for example, although the greater investment in R&D can increase the profitability and growth of the company, because, in the short term, it could generate an increase in sales, however, the perceived utility is affected by the costs associated with this type of innovative process.

This research raises the performance measured from the concept of competitive success proposed by Rubio and Aragón (Citation2002), who state that it depends on the factors of profitability: (a) the percentage of utility, (b) the market share and (c) sales growth. Likewise, they state that competitiveness is dynamic over time and the internal factors that affect companies can vary according to the context.

Relationship between innovation capabilities, innovation strategy and performance

Teece (Citation2017) describes the importance to analyse and understanding in a better way organisations from the perspective of their capabilities, including the capabilities to innovate with the purpose of managing to close the gaps that companies face with respect to their performance or competitiveness, carrying out focused strategic management in the development of the necessary and effective capabilities, which is especially useful to achieve the objectives and goals in unknown and uncertain contexts.

There are studies that relate innovation capabilities and performance in SMEs (Jalil, Ali, and Kamarulzaman Citation2022; Kő et al. Citation2022; Valdez-Juárez, Ramos-Escobar, and Borboa-Álvarez Citation2023), or innovation strategies and performance in SMEs (Nuryakin Nurjanah and Ardyan Citation2022; Radicic and Alkaraan Citation2022). However, it is little empirical evidence in the literature that allows for a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between innovation capabilities, innovation strategies and performance (Expósito and Sanchis-Llopis Citation2019; Oh, Cho, and Kim Citation2015). This research gap is even greater in the context of developing countries (Sahoo Citation2019).

In other hand, to generate innovation, the company establishes a system able to generate, disseminate and use innovations that have economic value, which is generally known as the technological innovation capabilities of the company (Yam et al. Citation2011). Innovation capabilities are a special asset of a company (Guan and Ma Citation2003) they relate to the skills and knowledge necessary to absorb, master and improve existing technologies, and to create new ones. They are a type of special assets or resources that include technology, product, process, knowledge, experience and organisation, which when developed and improved can lead to better performance in the organisation and therefore improve competitiveness (Maldonado-Guzmán et al. Citation2019; Yam et al. Citation2010).

Despite the importance of innovation capabilities on innovation results and business performance (Barbosa Ferreira, Coelho, and Weersma Citation2018; Teece Citation2017), in developing countries there is still limited empirical evidence on the subject (Zuñiga-Collazos et al. Citation2018, Citation2020). The absence of analysis is even more limited in SMEs.

Understanding innovation capabilities can help develop more successful strategies and generate better performance. In this sense, the company can use several strategies at the same time and the strategic orientations have a positive impact on innovation capabilities and performance. Rajapathirana and Hui (Citation2018) consider the capacity for innovation as a valuable asset to generate and maintain competitive advantages, as well as for the implementation of the strategy, which constitutes the central indicator of organisational performance.

For Bo and Qiuyan (Citation2012), SMEs are companies with a smaller production scale, with a simple internal organisation structure, independent production and operation, and different types of organisation, which use four types of strategy to generate innovation: acquisition, imitation, cooperation and R&D. In this sense, the strategic orientations depend on the development of capabilities, so that different orientations will lead to different capabilities but the strategic orientation does not always generate better performance (Asseraf and Shoham Citation2015).

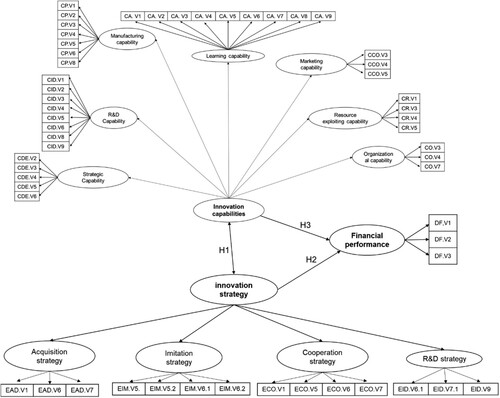

Based on the above, three hypotheses are proposed that are represented by the theoretical model in .

H1: Exist a direct and positive relationship between innovation capabilities and innovation strategies.

H2: Exist a direct and positive relationship between innovation strategies and financial performance.

H3: Exist a direct and positive relationship between innovation capabilities and financial performance.

Methodology

For this study, the structural modelling technique was used because the main purpose of this study is to test and estimate causal relationships between latent variables (constructs): innovation capabilities, innovation strategies and performance in Colombian SMEs from statistical data, argued from numological validity, based on the scientific literature review, the most appropriate technique for this study is the use of a structural equations model (Hair et al. Citation2021). According to the theoretical and empirical limitations of the relationships between the three constructs and their explanatory factors, the explanatory analysis is adequate to improve the understanding of the relationships studied as a basis for future simulations.

In this study, a non-probabilistic sampling was carried out based on companies registered in databases of innovation promotion programs, in such a way that companies that have or are working on innovation can be accessed. The following aspects were considered in the participating companies: (a) formally established companies; (b) classified as SMEs according to the classification of the Colombian Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism (Decree 957, 2019); (c) registered in databases of innovation promotion programs in Valle del Cauca; (d) who agree to participate in the research. A survey was applied to 250 SMEs, of which 136 were valid, that is, a 54.4% response. shows the characterisation of the sample.

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

describes the path model that was proposed for the validation of the constructs, as well as the causal relationships between them, the technique used for the analysis was through a structural equation model (SEM). The measurement of innovation capabilities was carried out with a questionnaire with a 7-point Likert scale, based on the studies by Guan and Ma (Citation2003) and Yam et al. (Citation2004, Citation2010, Citation2011). For its part, the measurement of the innovation strategy was carried out based on Damanpour and Aravind (Citation2012), OCDE (Citation2012), OCDE & Eurostat (Citation2018) . The measurement of financial performance was carried out based on Rubio and Aragón (Citation2002) and Yam et al. (Citation2010).

presents the detail of the measurement items and the theoretical references that support them. The method used to validate the scale in this research was the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the CFA is a statistical technique that is used to determine the reliability of measurement scales that explain the latent variables or constructs that may present possible relationships among themselves, although some items may have been used in previous studies, the CFA allows verify the reliability of the scale in different research contexts (Graham, Guthrie, and Thompson Citation2003). The software used was IBM SPSS V.23, which allowed obtaining the basic statistics of Cronbach's Alpha validation and standard deviations. EQS 6.2 software was used to run the structural equation model (SEM) and validate the proposed hypotheses.

Table 2. Measurement variables.

Results

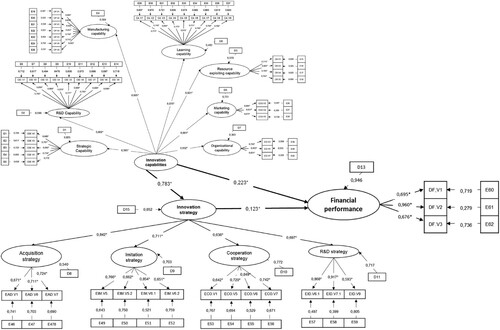

For the measurement scale to be reliable, Cronbach's alpha values equal to or greater than 0.70 are needed, and when the values exceed the 0.90, decisions could be made (Nunnally and Bernstein Citation1994). In addition, according to Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) a scale is reliable when the CRI is ≥0.70 and the AVE is ≥0.50, therefore, the results obtained in this study confirm the reliability of the scales used. Thus presents the results obtained from the alpha for the constructs studied, the standardised loads of each item in all dimensions, as well as the alpha, AVE and CRI for each dimension of innovation capabilities, innovation strategy and financial performance, for the items that had a value greater than 0.350. Those that did not meet the condition were considered, according to the Saxe and Weitz (Citation1982) criteria that they did not add value to the development of the scale and their elimination helped to improve the reliability of the final scale.

Table 3. Measurement model. Scale reliability.

The standardised coefficients of the CFA are adequate, being equal to or greater than 0.69 according to Bagozzi and Yi (Citation1988). The average of the standardised coefficients of each of the latent variables is above 0.70, according with parameters of Hair et al. (Citation2021) for a convergent validity.

The fit index of the structural model can be considered adequate when the indices BBNNFI, IFC, IFI obtain values higher than 0.9 (Hu and Bentler Citation1999; Ullman Citation2006). In this model, the values are close to 0.90 (BBNNFI = 0.862; CFI = 0.870; IFI = 0.872), which, despite being a little below, is not a condition for the model to be rejected, as Bentler (Citation2007) suggest and Sivo et al. (Citation2006) the size of the sample can influence the fit, as has happened in this research (n < 200).

The values obtained in RMSEA (0.059) indicate the presence of a good model (Brown Citation2006; Browne and Cudeck Citation1992). For this research, both in CFA and in the structural analysis, this index obtained adequate values. Finally, the significance of each of the validated hypotheses obtained values of p < 0.05. The results of the structural model are presented in .

Analysis and discussion

According to the results, hypothesis 1 (H1), which relates innovation capabilities and innovation strategy, presents a beta (significant p < 0.005) that could be considered high. This could mean an adequate explanation of the model. In addition, it contributes to the approaches of Bo and Qiuyan (Citation2012) by validating four types of strategies that companies use to innovate (acquisition, imitation, cooperation and R&D), as well as their relationship with innovation capabilities (Rajapathirana and Hui Citation2018). Specifically, in the context of SMEs, this study showed that innovation capabilities are strongly related to the innovation strategies they use, which could be explained by a highly uncertain and rival competitive environment.

In addition, this study showed that the relationship between the other two hypotheses that relate innovation strategies with financial performance (H2) and innovation capabilities with financial performance (H3), although significant, has a lower impact on the explanation of the model. This could be due to the low level of innovation results of the group of companies analysed, because of the use of strategies that demand high efforts in investment of resources such as R&D, as well as the need for long times before obtaining results (positives).

The results of the H2 are consistent with Rajapathirana and Hui (Citation2018) who state that innovation strategies determine performance. The results of the H3 are consistent with the existing evidence in the literature regarding the importance of innovation capabilities on the generation of innovation and business performance (Barbosa Ferreira, Coelho, and Weersma Citation2018; Teece Citation2017).

When observing the factor loads in the items, it was found that the R&D (0.650) and acquisition (0.627) strategies are the ones that most help to explain the proposed model. The imitation strategy (0.511) and the cooperation strategy (0.484) are the ones that contribute the least to the explanation. These results help to understand the low level of impact between the innovation strategy and financial performance, since SMEs have capacity and resource limitations for innovation management and require external knowledge and cooperation to improve their results. according to the literature consulted, but in the case of the SMEs analysed, there is evidence of a low contribution of cooperation to the explanation of the model. This could be interpreted in practice as a limited use of the benefits of cooperation to overcome the limitations and promote the results of innovation, possibly due to cultural aspects of the context.

In relation to innovation capabilities, it was found that the most significant are organisational capability (0.932) and learning capability (0.876). Likewise, a relatively high significance was found in the resource management capability (0.821), the production capability (0.805) and the R&D capability (0.802) and a moderately low significance in the commercialisation capability (0.661) and of strategic direction (0.565). These results can help explain the results obtained in the relationship between innovation capabilities and financial performance (H3), given that, despite making efforts to generate innovation, companies, especially SMEs, may not have a clear vision to help them better focus their innovation projects on their strategic goals and the market in which they compete to achieve competitive advantages.

Regarding financial performance, profit (0.736) is the item that makes the greatest contribution to explaining the model, along with sales growth (0.719) and, to a lesser extent, participation in product sales. innovators (0.279). These results in the companies analysed could be explained by a traditional focus of SMEs towards the short term that is evidenced in the interests of shareholders focused on profits rather than investment for innovative development and future sustainability.

When performing a more detailed analysis of the measurement items that explain the behaviour of the relationship model, it was found that, in the acquisition innovation strategy, the highest beta was the acquisition of external practices to organise and structure work (0.724), which is consistent with organisational capability (0.932), which obtained a high contribution to the explanation of the relationship between innovation capabilities and innovation strategy.

For its part, the item that obtained the highest beta in the imitation strategy was the management of production processes (0.854) based on the developments carried out by the sector leader. And the item that obtained the highest beta in the cooperation strategy was process management (0.849) through strategic alliances with suppliers and other organisations. These results could indicate that both the imitation strategy and the cooperation strategy are more focused on managing production processes and improving efficiency, rather than developing new products.

Finally, the item that obtained the highest beta in the R&D strategy was the development of innovation of key processes of products or services (0.917) that the company requires to compete in the sector, showing that the efforts in R&D are more focused on process management than on product development itself.

These results also help explain the financial performance, given that, in the companies analysed, innovation efforts are focused on the efficiency of processes and technology, rather than on the development of new products, which could increase sales. and profits, but not the share of innovative products in sales.

In summary, the validated hypotheses are consistent with what is described by Asseraf and Shoham (Citation2015) who state that the development of innovation capabilities is a determining factor of performance (H3) and that the strategic orientation depends on the level of innovation capabilities (H1). It also contributes to the work of Rajapathirana and Hui (Citation2018) who consider the capacity for innovation as a valuable asset to generate and maintain competitive advantages, as well as for the implementation of the strategy, which constitutes the central indicator of organisational performance (H2).

Conclusion

The main conclusion and contribution is that this study allowed us to empirically validate and understand in an integrated way the relationships between the theoretical constructs and provides a new vision of the causal relationships between three constructs at the same time, that is, innovation capabilities, innovation strategies and performance, that at the SME scale and in the context of a developing country with limited theoretical and empirical development.

The results of the analysis of the measurement model that relates innovation capabilities with the innovation strategy and financial performance (hypotheses H1, H2 and H3) are confirmed. It is evident that, according to the innovation capabilities, SMEs determine the innovation strategy to use. However, not all strategies impact financial performance in the same way. Cooperation strategies should be used more by SMEs since it allows them to make up for the lack of internal capabilities that they require to innovate.

By achieving a better understanding of the dimensions that make up innovation capabilities and the strategies that generate better performance in SMEs, companies can make decisions to prioritise and optimise their resources with strategies that could be more effective in relation to financial performance.

Other studies have evaluated strategies in isolation, which has limited the comparison between the strategies, in addition to not considering the relationship between innovation capabilities and the type of strategies that could generate better financial performance according to the capabilities in SMEs. For example, adopting acquisition strategies generates a greater focus of SMEs on buying new technologies to be exploited. They can also adopt strategies already validated by the competition (imitation) so that they can be adapted and improved, better impacting financial performance.

According to the results obtained in the model, it is possible to affirm that the use of R&D strategies in SMEs requires a significant amount of financial resources, great effort and time, but the results are not easy to achieve. However, it is one of the strategies that best explains this phenomenon in the companies analysed and the effort does not reflect what is expected for financial performance, since it obtained a relatively low beta. Therefore, it is important that companies choose strategies to innovate according to their capabilities to generate better innovation results and competitive advantages.

This study had some limitations, such as the use of a population limited to a specific region of a developing country. In addition, access to the sample was affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and therefore it is recommended to expand it in subsequent studies. On the other hand, since this is a relatively new empirical analysis, it opens the opportunity to continue validating the constructs analysed in other contexts. It is also important to analyse the impact that these relationships could have by influencing other constructs such as the change in the technological trajectory, the barriers to management and the investment in innovation capabilities.

Despite the diversity of research using SEM, this study failed to identify enough similar research in the Colombian context and in SMEs. This was a limitation but also an advance in closing knowledge gaps. The findings of this research show the need to continue delving into the subject and continue validating the relationships between the constructs studied in multiple contexts.

Finally, this study is the basis for longitudinal studies that, after obtaining sufficient data at different time frequencies, allow predictive models, simulations and optimisations to be made, opening up new analysis opportunities that are complemented by other techniques, such as those that use artificial intelligence (Bao and Wang Citation2022; Lee et al. Citation2022) that are novel and could adequately provide new explanations of the problem.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Isabel Cristina Quintero Sepúlveda

Isabel Cristina Quintero Sepúlveda Doctor in Technology and Innovation Management from Pontificia Bolivariana University, Colombia. Graduated of the master's in administration, from the Universidad del Valle-Colombia. Full Professor-Researcher in Business Administration at the Pontificia Bolivariana University, Colombia. Professional experience in service companies in strategic planning areas and project management. Specialties: Researcher in Business Administration (innovation capabilities and strategy). Business Consultant in areas of: Strategic Planning and Innovation.

Alexander Zúñiga Collazos

Alexander Zuñiga-Collazos Doctor in Scientific Perspectives on Tourism and Tourism Business Management from the University of las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain. Graduated with a Meritorious Doctoral thesis. Outstanding Evaluation Mention ‘Cum Laude’. Illustrious Graduate of the master’s in administration, from the Universidad del Valle-Colombia. Until 2023, I was full Professor-Researcher and Director Doctorate in Business Administration at the University of San Buenaventura-Cali. Currently, full-time professor at the Universidad del Valle, Colombia. School of Economics. International Visiting Professor at the iMBA at the University of Illnois - USA in 2022; School of Hotel, Restaurant and Tourism Management of the University of South Carolina - USA in 2014 and TIDES Research Center of Spain in 2015. Member (Representative by Academy) of the Board of Directors of the Cali Conventions and Visitors Bureau e Member of the Tourist Information System (SITUR) of Valle del Cauca - Colombia. Specialties: Senior Researcher (MinScience - Col) in Business Administration (Tourism focus). Business Consultant in: Areas of: Tourism Marketing, Strategic Planning and Innovation.

References

- Afshar Jahanshahi, A., and A. Brem. 2020. “Entrepreneurs in Post-Sanctions Iran: Innovation or Imitation Under Conditions of Perceived Environmental Uncertainty?” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 37 (2): 531–551. doi:10.1007/s10490-018-9618-4.

- Ali, M. 2021. “Imitation or Innovation: To What Extent Do Exploitative Learning and Exploratory Learning Foster Imitation Strategy and Innovation Strategy for Sustained Competitive Advantage?*.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 165, 120527. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120527.

- Asseraf, Y., and A. Shoham. 2015. “The Relationships Between International Orientations, Capabilities, Strategies and Performance: A Theorical Perspective.” Ideas in Marketing: Finding the New and Polishing the Old. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10951-0.

- Bagozzi, R. P., and Y. Yi. 1988. “On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 16 (1): 74–94. doi:10.1007/BF02723327.

- Bao, Y., and Y. Wang. 2022. “Factor Space: The New Science of Causal Relationship.” Annals of Data Science 9 (3): 555–570. doi:10.1007/s40745-022-00396-7.

- Barbosa Ferreira, J. A., A. Coelho, and L. A. Weersma. 2018. “The Mediating Effect of Strategic Orientation, Innovation Capabilities and Managerial Capabilities among Exploration and Exploitation, Competitive Advantage and Firm’s Performance.” Contaduria y Administracion 64 (1): 66. doi:10.22201/fca.24488410e.2019.1918.

- Barge-Gil, A. 2009. “Cooperation-based Innovators and Peripheral Cooperators: An Empirical Analysis of Their Characteristics and Behavior.” Technovation 30 (3): 195–206. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2009.11.004

- Bature, S. W., R. M. Sallehuddin, N. A. Rosli, and S. Saad. 2018. “Proactiveness, Innovativeness and Firm Performance: The Mediating Role of Organizational Capability.” Academy of Strategic Management Journal 17 (5): 1–14.

- Bentler, P. M. 2007. “On Tests and Indices for Evaluating Structural Models.” Personality and Individual Differences 42 (5): 825–829. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.024.

- Bo, Z., and T. Qiuyan. 2012. “Research of SMEs’ Technology Innovation Model from Multiple Perspectives.” Chinese Management Studies 6 (1): 124–136. doi:10.1108/17506141211213825.

- Bouncken, R., and S. Kraus. 2013. “Innovation in Knowledge-Intensive Industries: The Double-Edged Sword of Coopetition.” Journal of Business Research 66 (10): 2060–2070. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.032

- Brown, T. A. 2006. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York: The Guilford Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-07729-000.

- Browne, M. W., and R. Cudeck. 1992. “Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit.” Sociological Methods & Research 21 (2): 230–258. doi:10.1177/0049124192021002005.

- Cammarano, A., F. Michelino, and M. Caputo. 2019. “Open Innovation Practices for Knowledge Acquisition and Their Effects on Innovation Output.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 31 (11): 1297–1313. doi:10.1080/09537325.2019.1606420.

- Chun, H., and S. B. Mun. 2011. “Determinants of R&D Cooperation in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises.” Small Business Economics 39: 419–436. doi:10.1007/%2Fs11187-010-9312-5.

- Cornell University, INSEAD, & WIPO. 2019. The Global Innovation Index 2019: Creating Healthy Lives—The Future of Medical Innovation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) & Confederation of Indian Industry (CII). https://www.globalinnovationindex.org/userfiles/file/reportpdf/gii-full-report-2019.pdf.

- Damanpour, F., and D. Aravind. 2012. “Managerial Innovation: Conceptions, Processes, and Antecedents.” Management and Organization Review 8 (2): 423–454. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8784.2011.00233.x.

- de Resende, L. M. M., I. Volski, L. Mendes Betim, G. D. Gomes de Carvalho, R. de Barrose, and F. Pietrobelli Senger. 2018. “Critical Success Factors in Coopetition: Evidence on a Business Network.” Industrial Marketing Management 68: 177–187. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0019850117302390.

- Devece, C., D. E. Ribeiro-Soriano, and D. Palacios-Marqués. 2019. “Coopetition as the New Trend in Inter-Firm Alliances: Literature Review and Research Patterns.” Review of Managerial Science 13: 207–226. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007s11846-017-0245-0.

- Dosi, G. 1992. “Fuentes, Métodos y Efectos Microeconómicos de la Innovación.” Revista Internacional de Economía 22: 269–332. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=273987.

- Dunlap, D., E. F. McDonough, R. Mudambi, and T. Swift. 2016. “Making Up Is Hard to Do: Knowledge Acquisition Strategies and the Nature of New Product Innovation.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 33 (4): 472–491. doi:10.1111/jpim.12298.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., and J. Martin. 2000. “Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They?” Strategic Management Journal 21: 1105–1121. http://mail.tku.edu.tw/myday/teaching/992/SEC/S/992SEC_T3_Paper_20100415_Eisenhardt Martin (2000) - Dynamic capabilities what are they.pdf.

- Expósito, A., and J. A. Sanchis-Llopis. 2019. “The Relationship Between Types of Innovation and SMEs’ Performance: A Multi-Dimensional Empirical Assessment.” Eurasian Business Review 9: 115–135. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs40821-018-00116-3.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error.” Journal of Marketing Research 18 (February): 39–50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3151312?origin=crossref&seq=1.

- Grabowski, W., and A. Staszewska-Bystrova. 2020. “The Role of Public Support for Innovativeness in SMEs Across European Countries and Sectors of Economic Activity.” Sustainability (Switzerland) 12 (10), 4143. doi:10.3390/su12104143.

- Graham, J. M., A. C. Guthrie, and B. Thompson. 2003. “Consequences of not Interpreting Structure Coefficients in Published CFA Research: A Reminder.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 10 (1): 142–153. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1207S15328007SEM1001_7?needAccess=true.

- Guan, J., and N. Ma. 2003. “Innovative Capability and Export Performance of Chinese Firms.” Technovation 23 (9): 737–747. doi:10.1016/S0166-4972(02)00013-5.

- Gunday, G., G. Ulusoy, K. Kilic, and L. Alpkan. 2011. “Effects of Innovation Types on Firm Performance.” International Journal of Production Economics 133 (2): 662–676. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2011.05.014.

- Hair, J. F., C. B. Astrachan, O. I. Moisescu, L. Radomir, M. Sarstedt, S. Vaithilingam, and C. M. Ringle. 2021. “Executing and Interpreting Applications of PLS-SEM: Updates for Family Business Researchers.” Journal of Family Business Strategy 12 (3), 100392. doi:10.1016/j.jfbs.2020.100392.

- Henttonen, K., and P. Hurmelinna-Laukkanen. 2014. “Determinants of R&D Collaboration: An Empirical Analysis.” International Journal of Innovation Management 18 (4): 2601–2621. https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/abs/10.1142S1363919614500261.

- Hervas-Oliver, J. L., C. Boronat-Moll, and F. Sempere-Ripoll. 2016. “On Process Innovation Capabilities in SMEs: A Taxonomy of Process-Oriented Innovative SMEs.” Journal of Small Business Management 54 (April 2015): 113–134. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12293.

- Hu, L.-T., and P. M. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus new Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6 (1): 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Jalil, M. F., A. S. Ali, and R. Kamarulzaman. 2022. “Does Innovation Capability Improve SME Performance in Malaysia? The Mediating Effect of Technology Adoption.” The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 23: 253–267. doi:10.1177/14657503211048967.

- Klimas, P., and W. Czakon. 2018. “Organizational Innovativeness and Coopetition: A Study of Video Game Developers.” Review of Managerial Science 12: 469–497. doi:10.1007/s11846-017-0269-5.

- Kő, A., A. Mitev, T. Kovács, P. Fehér, and Z. Szabó. 2022. “Digital Agility, Digital Competitiveness, and Innovative Performance of SMEs.” Journal of Competitiveness 14 (4): 78–96. http://unipub.lib.uni-corvinus.hu/7908/1/466.pdf.

- Kraus, S., P. Klimas, J. Gast, and T. Stephan. 2018. “Sleeping with Competitors: Forms, Antecedents and Outcomes of Coopetition of Small and Medium-Sized Craft Beer Breweries.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 25 (1): 50–66. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-09-2017-0356.

- Lee, A., I. Inceoglu, O. Hauser, and M. Greene. 2022. “Determining Causal Relationships in Leadership Research Using Machine Learning: The Powerful Synergy of Experiments and Data Science.” The Leadership Quarterly 33 (5): 101426. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2020.101426.

- Liu, Y., X. Wei, and Z. Li. 2019. “Improving Design and Creative Ability of High School Students Through Project Based Learning.” Proceedings – International Joint Conference on Information, Media, and Engineering, IJCIME 2019 (pp. 338–341). doi:10.1109/IJCIME49369.2019.00074.

- Maldonado-Guzmán, G., J. A. Garza-Reyes, S. Y. Pinzón-Castro, and V. Kumar. 2019. “Innovation Capabilities and Performance: Are They Truly Linked in SMEs?” International Journal of Innovation Science 11 (1): 48–62. doi:10.1108/IJIS-12-2017-0139.

- Mata, J., and M. Woerter. 2013. “Risky Innovation: The Impact of Internal and External R&D Strategies upon the Distribution of Returns.” Research Policy 42 (2): 495–501. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2012.08.004.

- Mawson, S., and R. Brown. 2016. “Entrepreneurial Acquisitions, Open Innovation and UK High Growth SMEs.” Industry and Innovation 24 (4): 382–402. doi:10.1080/13662716.2016.1244764.

- Nunnally, J., and I. Bernstein. 1994. Psychometric Theory. McGraw- Hill. https://books.google.com.co/books/about/Psychometric_Theory_3E.html?id=_6R_f3G58JsC&redir_esc=y.

- Nuryakin Nurjanah, A., and E. Ardyan. 2022. “Open Innovation Strategies and Smes’ Performance: The Mediating Role of Eco-Innovation in Environmental Uncertainty.” Management Systems in Production Engineering 30 (3): 214–222. doi:10.2478/mspe-2022-0027.

- OCDE. 2012. Innovación en las empresas. OCDE. https://docplayer.es/17603362-Innovacion-en-las-empresas-una-perspectiva-microeconomica.html.

- OECD/Eurostat. 2018. Oslo Manual 2018: Guidelines for Collecting, Reporting and Using Data on Innovation (4th ed). OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264304604-en.

- Oh, C., Y. Cho, and W. Kim. 2015. “The Effect of a Firm’s Strategic Innovation Decisions on Its Market Performance.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 27 (1): 39–53. doi:10.1080/09537325.2014.945413.

- Radicic, D., and F. Alkaraan. 2022. “Relative Effectiveness of Open Innovation Strategies in Single and Complex SME Innovators.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 1–14. doi:10.1080/09537325.2022.2130042.

- Rajapathirana, R. P. J., and Y. Hui. 2018. “Relationship Between Innovation Capability, Innovation Type, and Firm Performance.” Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 3: 44–55. doi:10.1016/j.jik.2017.06.002.

- Rehm, S. V., and L. Goel. 2017. “Using Information Systems to Achieve Complementarity in SME Innovation Networks.” Information and Management 54 (4): 438–451. doi:10.1016/j.im.2016.10.003.

- Richter, N., P. Jackson, and T. Schildhauer. 2018. “Radical Innovation Using Corporate Accelerators: A Program Approach”. In Entrepreneurial Innovation and Leadership: Preparing for a Digital Future, edited by N. Richter, P. Jackson, and T. Schildhauer, 99–108. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-71737-1_9.

- Rosenbusch, N., J. Brinckmann, and A. Bausch. 2011. “Is Innovation Always Beneficial? A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship Between Innovation and Performance in SMEs.” Journal of Business Venturing 26 (4): 441–457. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.12.002.

- Rubio, B. A., and S. A. Aragón. 2002. “Factores Explicativos del éxito Competitivo. Un Estudio Empírico en la Pyme.” Cuadernos de Gestion 2 (1): 49–63.

- Sahoo, S. 2019. “Quality Management, Innovation Capability and Firm Performance: Empirical Insights from Indian Manufacturing SMEs.” The TQM Journal 31 (6): 1003–1027. doi:10.1108/TQM-04-2019-0092.

- Saxe, R., and B. A. Weitz. 1982. “The SOCO Scale: A Measure of the Customer Orientation of Salespeople.” Journal of Marketing Research 19 (3): 343–351. doi:10.1177/002224378201900307

- Schwab, K. 2019. The Global Competitiveness Report 2019. Genova: World Economic Forum. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2019.pdf.

- Sivo, S. A., F. A. N. Xitao, E. L. Witta, and J. T. Willse. 2006. “The Search for “Optimal” Cutoff Properties: Fit Index Criteria in Structural Equation Modeling.” The Journal of Experimental Education 74 (3): 267–288. doi:10.3200/JEXE.74.3.267-288.

- Søndergaard, H. A., M. P. Knudsen, and N. S. Laugesen. 2021. “The Catch-22 in Strategizing for Radical Innovation.” Technology Innovation Management Review 11 (3): 4–16. doi:10.22215/timreview/1425.

- Teece, David J. 2017. “Towards a Capability Theory of (Innovating) Firms: Implications for Management and Policy.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 41 (3): 693–720. doi:10.1093/cje/bew063.

- Teece, D. J. 2018. “Dynamic Capabilities as (Workable) Management Systems Theory.” Journal of Management and Organization 24 (3): 359–368. doi:10.1017/jmo.2017.75.

- Teece, D. J., G. Pisano, and A. Shuen. 1997. “Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management.” Strategic Management Journal 18 (7): 509–533. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z

- Ullman, J. B. 2006. “Structural Equation Modeling.” In Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed. edited by B. G. Tabachnick, and L. S. Fidell, 653–771. Boston, MA: Pearson. https://www.pearson.com/us/higher-education/product/Tabachnick-Using-Multivariate-Statistics-5th-Edition/9780205459384.html.

- Valdez-Juárez, L. E., E. A. Ramos-Escobar, and E. P. Borboa-Álvarez. 2023. “Reconfiguration of Technological and Innovation Capabilities in Mexican SMEs: Effective Strategies for Corporate Performance in Emerging Economies.” Administrative Sciences 13 (1): 15. doi:10.3390/admsci13010015.

- Valentini, G., and M. C. Di Guardo. 2012. “M&A and the Profile of Inventive Activity.” Strategic Organization 10 (4): 384–405. doi:10.1177/1476127012457980.

- Velázquez Castro, J. A., E. Cruz Coria, and E. E. Vargas Martínez. 2018. “Cooperación Empresarial Para el Fomento de la Innovación en la Pyme Turística.” Revista de Ciencias Sociales (Ve) 24 (3): 9–19. https://www.redalyc.org/jatsRepo/280/28059580002/index.html.

- Wang, N., M. Xiao, and I. Savin. 2021. “Complementarity Effect in the Innovation Strategy: Internal R&D and Acquisition of Capital with Embodied Technology.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 46 (2): 459–482. doi:10.1007/s10961-020-09780-y.

- Weber, B., and S. Heidenreich. 2018. “When and with Whom to Cooperate? Investigating Effects of Cooperation Stage and Type on Innovation Capabilities and Success.” Long Range Planning. 51 (2): 334–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2017.07.003.

- World Economic Forum. 2018. The Global Competitiveness Report 2018. In World Economic Forum Reports 2018. ISBN-13: 978-92-95044-73-9.

- Wu, J., K. R. Harrigan, S. H. Ang, and Z. Wu. 2019. “The Impact of Imitation Strategy and R&D Resources on Incremental and Radical Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Firms.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 44 (1): 210–230. doi:10.1007/s10961-017-9621-9.

- Wu, J., X. Zhang, S. Zhuo, M. Meyer, B. Li, and H. Yan. 2020. “The Imitation-Innovation Link, External Knowledge Search and China’s Innovation System.” Journal of Intellectual Capital 21 (5): 727–752. doi:10.1108/JIC-05-2019-0092.

- Xie, X., Y. Gao, Z. Zang, and X. Meng. 2020. “Collaborative Ties and Ambidextrous Innovation: Insights from Internal and External Knowledge Acquisition.” Industry and Innovation 27 (3): 285–310. doi:10.1080/13662716.2019.1633909.

- Yam, R. C. M., J. C. Guan, K. F. Pun, and E. P. Y. Tang. 2004. “An Audit of Technological Innovation Capabilities in Chinese Firms: Some Empirical Findings in Beijing, China.” Research Policy 33 (8): 1123–1140. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2004.05.004.

- Yam, R. C. M., W. Lo, E. P. Y. Tang, and A. K. W. Lau. 2011. “Analysis of Sources of Innovation, Technological Innovation Capabilities, and Performance: An Empirical Study of Hong Kong Manufacturing Industries.” Research Policy 40 (3): 391–402. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.10.013.

- Yam, R. C. M., W. Lo, E. P. Y. Tang, and A. K. W. Law. 2010. “Technological Innovation Capabilities and Firm Performance.” World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology 42: 1009–1017.

- Zuñiga-Collazos, A., M. Castillo-Palacio, R. A. Tabarquino-Muñoz, and E. Collazos-Zuñiga. 2018. “Process Innovations in Tourist Companies.” International Journal for Quality Research 12 (3), doi:10.18421/IJQR12.03-08.

- Zuñiga-Collazos, A., L. M. Padilla-Delgado, R. Harrill, and M. Castillo-Palacio. 2020. “Negative Effect of Innovation on Organizational Competitiveness on Tourism Companies.” Tourism Analysis 25: 455–461. doi:10.3727/108354220X15758301241873.