ABSTRACT

This study conducts a systematic literature review of San Diego’s innovation ecosystem to analyse its evolution, dynamics, the most influential (key) stakeholders, and success factors. 1,405 documents from Scopus and 809 documents from Web of Science (WoS) were retrieved and analysed to obtain a final sample of twenty articles. The ecosystem’s key organisational stakeholders were identified as UC San Diego, research institutes, venture capitalists, pioneer and leading companies and intermediary organisations. Regarding success factors, key political factors include research funding, other public funding and policies that foster, for example, the actors’ geographical proximity. Key economic factors include start-up support systems, company acquisitions and initial public offerings (IPOs). Several vital social factors, such as collaboration, social networks and risk-taking culture, were also identified. Finally, the key technological success factors include technology transfer, specific focus areas and critical mass in research and development. This systematic review, complemented by expert interviews, provides a comprehensive view and validation of the stakeholders and factors that have contributed to the emergence, evolution and dynamics of the innovation ecosystem. The study also exemplifies an originally nonleading city’s path to success, which can provide valuable innovation policy and planning insights for other nonleading regions.

1. Introduction

Knowledge and innovation networks – as well as different types of ecosystems, their actors and success factors – have fascinated researchers for decades (Youtie et al. Citation2021). While knowledge ecosystems focus on knowledge exploration and business ecosystems on creating value for customers, innovation ecosystems focus on the integration of knowledge and business. Innovation ecosystems consist of stakeholders that interact in innovation and are located geographically close to each other. (Valkokari Citation2015) As Granstrand and Holgersson (Citation2020) stated, ‘An innovation ecosystem is the evolving set of actors, activities, and artefacts, and the institutions and relations, including complementary and substitute relations, that are important for the innovative performance of an actor or a population of actors’.

Over the years, researchers have attempted to identify the factors that drive innovation growth and success, and many countries and regions have searched for a recipe for creating successful innovation ecosystems and innovation policies that will contribute to the transformation towards more sustainable economies (Steward Citation2012). The USA is often considered a global innovation leader, and especially the Silicon Valley innovation ecosystem has been studied extensively (e.g. Kenney Citation2000; Etzkowitz Citation2019). However, sustainability and system-level transformations require not only existing innovation-leading countries and metropolises, but also areas and cities with fewer resources, for example, from the viewpoint of large company headquarters. The emergence and evolution of geographically remote innovation ecosystems, such as San Diego, have received much less attention, although they provide many regions with relevant comparisons and benchmarks. Over time, San Diego has evolved from a remote, small city to a leading location in biotechnology, life sciences and wireless technology – a position that many smaller cities also aim for in their specialisation areas. The current study aims to gain understanding, how an originally nonleading city can evolve into a leading innovation ecosystem.

Previous studies have called for more research on the dynamic nature of ecosystems’ development and their emergence and evolution, rather than static analysis of ecosystem characteristics and operations (e.g. Liu et al. Citation2022). Many studies (e.g. Walcott Citation2002; Casper Citation2007; Kim Citation2015) have provided insights into different aspects of innovation in San Diego and how the ecosystem emerged. However, a systematic literature review of San Diego’s innovation ecosystem has not been conducted. The present study reviews the literature to provide a comprehensive view of the evolution of an originally nonleading city to one of the world’s leading innovation ecosystems by focusing especially on the ecosystem’s stakeholders and success factors. Compared with single case studies, this study provides a long-term analysis of the evolution of the San Diego ecosystem, covering academic research publications produced over the past twenty years. The in-depth literature-based review complemented by expert interviews provides confirmation and validation of the stakeholders and success factors during the innovation ecosystem’s evolution. The following research questions (RQs) are formulated:

RQ1) Who have been the key stakeholders in San Diego’s innovation ecosystem during its evolution?

RQ2) What are the key factors that have influenced the innovation ecosystem dynamics and contributed to its success?

2. Background: the evolution of San Diego’s innovation ecosystem

San Diego started to invest in hospitals and health research clinics in the 1880s. The Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) was founded in 1903, and it was later acquired by the University of California (UC). The aviation industry emerged in the 1920s – 1940s, and World War II resulted in the expansion of the military base and aircraft industry (Kim Citation2015; Walshok and Shragge Citation2014). The Scripps Research Institute, the Salk Institute and UC San Diego (UCSD) were founded in the 1950s and 1960s and were critical events in the innovation ecosystem’s birth. Prior to this, the city of San Diego had made land zoning decisions that enabled the geographical proximity of UCSD, research institutes and companies. The city reinforced its plan for a life sciences research area in the 1970s (Kim Citation2015). UC’s decision to establish a campus in San Diego was driven by the collaboration between the SIO and the U.S. Navy and the expansion of basic research and development (R&D) for defence and aerospace applications. The UCSD aimed to build excellence in biology and the natural sciences, and it recruited top researchers and scientists (Walshok and Shragge Citation2014). UCSD also integrated its medical school with basic science departments. A 1,000-bed veteran hospital opened on campus in 1972 (Casper Citation2014).

In the 1970s, federal government funding, especially from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the collaboration of the UCSD, the Scripps Research Institute and the Salk Institute, expanded San Diego’s research capacity. By the mid-1980s, the innovation ecosystem had gained powerful R&D capacity, which also attracted venture capitalists (VCs) and international companies. Research-based pioneer start-ups, such as Hybritech in biotechnology and Linkabit in wireless technology, further strengthened the ecosystem (Kim Citation2015; Walshok and Shragge Citation2014). Hybritech launched several products and conducted a successful initial public offering (IPO) (Casper Citation2014; Walcott Citation2002). After acquisition by Eli Lilly in 1986, many people left Hybritech to become entrepreneurs. Despite the wealth gained from the acquisition, the VC funding was mainly from the San Francisco Bay area, and management had to be recruited from outside the region to a new, high-risk industry. San Diego’s remote location required collaboration and partnering, which was enabled by the short geographical distances between local stakeholders, which became a significant characteristic of the innovation ecosystem (Casper Citation2014).

Despite its initial success, San Diego’s innovation ecosystem suffered from a gap between science and business, as well as insufficient capital and intellectual property right (IPR) competence. San Diego failed to attract large companies and research consortia. For example, in the mid-1980s, the San Diego Economic Development Corporation (SDEDC), city government and UCSD tried to attract Microelectronics and Computer Consortium (MCC) to San Diego, but the MCC selected Austin because of strong support from the Texas government and its efforts to develop R&D capacity at the University of Texas (Gibson and Oden Citation2019). The military sector’s downsizing increased unemployment, and the SDEDC and UCSD started planning how to increase collaboration between research and business (Walshok and Shragge Citation2014). CONNECT, a nonprofit intermediary organisation, was founded in 1985. The aim was to develop a bottom-up, privately funded innovation-acceleration programme that was based at UCSD. CONNECT increased collaboration and trust between innovation ecosystem stakeholders (Majava et al. Citation2016b). For example, the Springboard programme provided coaching and mentoring for entrepreneurs.

In the 1990s, San Diego had become the world’s third-largest location in the biotechnology industry, home to hundreds of start-ups, small – and medium-sized companies, and Qualcomm, one of the world’s leading wireless technology companies. Employment in the life sciences sector increased from 7,500 in 1997 to 23,000 in 2007 (Kim Citation2015). The innovation ecosystem had developed a bottom-up, self-organised structure based on a very strong research-based foundation. Various stakeholders contributed to its success: universities, research institutes, accelerators, incubators, angel investors, VCs, incumbent firms, trade organisations, service providers and local, state and federal governments (Majava et al. Citation2016a).

3. Research method and process

3.1. Method and data collection

A systematic literature review method was utilised to address the RQs. The research process followed the phases presented by Xiao and Watson (Citation2019), including (1) research problem formulation, (2) review protocol development and validation, (3) literature search, (4) screening for inclusion, (5) quality assessment, (6) data extraction, (7) data analysis and synthesis and (8) reporting of the findings.

In the research problem formulation stage, the RQs were created based on the study’s objectives. Next, the review protocol was created and validated. In this phase, the search strategy, inclusion and quality assessment criteria, screening procedures and strategies for data extraction, synthesis and reporting were defined. Alternative combinations of different search terms derived from the RQs were created and tested using several trial searches. Based on the trials, the final search terms were selected. The university library information specialists’ guidance was also utilised in the review protocol creation and validation phase.

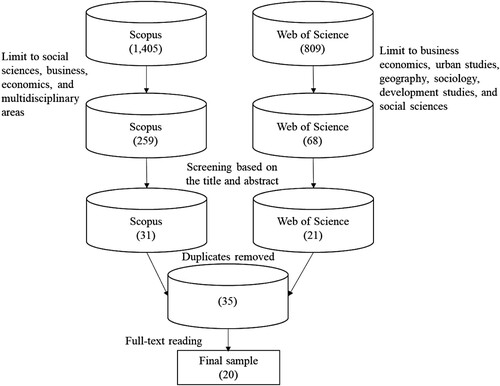

A literature search was conducted for peer-reviewed, English-language articles in Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) databases. The final search string was as follows: ‘San Diego’ AND innovation OR cluster OR network OR ecosystem. The search included the article title, abstract and keywords. Initially, 1,405 documents from Scopus and 809 from WoS were retrieved. The subject areas were then refined to social sciences, business, economics and multidisciplinary areas (Scopus) as well as business economics, urban studies, geography, sociology, development studies and social sciences (WoS). After this refinement, 259 documents in Scopus and 68 in WoS remained. These documents were further screened based on the title and abstract, which resulted in 31 articles in Scopus and 21 in WoS. Next, duplicates were removed, and the remaining sample consisted of 35 articles. The full texts were read, and a quality assessment was performed based on the articles’ publication channels as well as their research, data collection and analysis methods and theoretical approaches to ensure that the included articles provided objective, valid and reliable information. Furthermore, articles that were not within the study’s scope were excluded ().

Table 1. Exclusion and inclusion criteria for the full-text review.

The final sample included twenty articles. presents the steps in the material collection.

In the material analysis and data extraction, the studies’ objectives, research methods, data used, target industries and main findings were analysed. In addition, meta-data on the articles were collected. Finally, an in-depth analysis of the articles was performed to identify which innovation ecosystem stakeholders and success factors were emphasised.

To support the findings of the systematic literature review, interviews with eight experts in San Diego’s innovation ecosystem were utilised. Three experts had backgrounds at CONNECT and UCSD, one at BIOCOM, three as entrepreneurs and one as an angel investor. The interviews focused on San Diego’s innovation ecosystem’s characteristics, key stakeholders and the factors that have contributed to its success. The interviews lasted approximately one hour on average, and they were recorded, transcribed and analysed. The results were compared with the results of the systematic literature review. The findings are presented and discussed in sections 4 and 5.

3.2. The final sample

Based on the systematic literature review, the main studies were identified ().

Table 2. Articles in the final literature sample.

Next, each study is briefly presented. Walcott (Citation2001) analysed life science companies’ acquisitions in four different locations – Indianapolis, Research Triangle, San Diego and Shanghai – and emphasised the importance of structured and informal information exchange networks in site selection. Walshok et al. (Citation2002) studied San Diego’s evolution and transformation into a leading location in biotechnology and wireless communications. Three critical characteristics were stressed: the store of intellectual capital, the business and financial networks and the skills and knowledge of human capital.

Powell et al. (Citation2002) conducted a multiple case study on biotechnology in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, the District of Columbia, Chicago, Houston, San Diego, the San Francisco Bay area and Seattle. They analysed the geographical concentration of two critical factors, ideas (i.e. research-intensive biotech firms) and money (VC firms) because the biotech industry has a unique dual dependence on basic science and venture financing. The role of tacit knowledge, physical contact and the capability to learn and coordinate multiple projects were found to be important spatial factors in the biotechnology industry. Differences between the types of investments by Boston, New York and West Coast VC firms were also identified. Walcott (Citation2002), in turn, focused solely on bioscience (life sciences) in San Diego. She identified five key success factors: an outstanding research university, advocacy leadership, risk funding, an entrepreneurial culture and proper real estate that is supported by an intensive information exchange network.

Williams (Citation2005) analysed patent data and found that technological innovation in San Diego has contributed to high average annual growth rates in wages, business formation and new investment funding received. Cooke (Citation2006) analysed the biotechnology industry based on collaborations between leading scientists and their institutes and identified the strongest global locations as Boston, San Diego and San Francisco. Sable (Citation2007) concluded that despite its positive economic effects, high technology (biotechnology) also has negative impacts on local development, especially for low and semiskilled people in the Boston and San Diego areas. These impacts include urban sprawl, transportation congestion, a lack of affordable housing and gentrification.

Casper (Citation2007) focused on social networks and mobility between companies in San Diego’s biotechnology cluster. He found that labour mobility created a large network that links managers and firms. The pioneer company Hybritech formed the network core, which provided the basis for growth in the San Diego region. Lakoff (Citation2008) focused on wireless communications. He argued that the founding of UCSD was critical for attracting people who founded Qualcomm, one of the world’s leading technology companies.

Walshok and Shragge (Citation2012) studied San Diego’s evolution in several industry sectors; they argued that challenger cities such as San Diego often develop adaptable experimentation and risk-taking initiatives for innovation, such as the CONNECT programme, which has been adopted by multiple cities around the world. Kim and Jeong (Citation2014) conducted a case study on biotechnology in San Diego and highlighted the role of CONNECT as a platform that strengthened collaboration and interaction, as well as helped new entrepreneurs. The success of CONNECT was based on involving the wide community, bridging separated sectors, dedicated leadership and a bottom-up process.

Walshok and Lee (Citation2014) focused on biotechnology and wireless communications in San Diego and argued that these industries are anchored by the intellectual creativity of UCSD and world-class research centres (e.g. the Scripps Research Institute), which has enabled the creation of tens of thousands of new technology jobs that compensated for the loss of 27,000 defence manufacturing jobs in San Diego in the 1990s. Kim (Citation2015) analysed San Diego’s biotechnology cluster development. He found that the existence of many small biotechnology companies rather than a group of large firms, a continuous talent flow, and leadership that strengthened collaborations contributed to knowledge creation and accumulation, which are important for producing start-up firms. San Diego’s strength in stimulating entrepreneurship and innovation is based on the creation and utilisation of knowledge and practices via entrepreneurs’ interactions and participation. Majava et al. (Citation2016a) analysed the life sciences business ecosystem in San Diego and demonstrated its bottom-up nature. Majava et al. (Citation2016b) argued that trust is important for an ecosystem’s success and that an intermediary organisation, such as CONNECT, can increase trust among actors.

Majava et al. (Citation2017) analysed innovation-driven enterprises’ stakeholders in San Diego’s wireless technology ecosystem and proposed that these firms can exploit spatial ecosystems by interacting with various stakeholders and gaining access to local resources. Sumikura, Sugai, and Maki (Citation2018) studied the involvement of star scientists in corporate activities in San Diego to foster an innovation ecosystem with firms. Tvedt (Citation2019) analysed how cleantech clusters emerge by studying Cleantech San Diego, Green Tech Valley in Austria and Sustainable Nation Ireland in the Dublin region. He argued that these clusters are an outcome of strategic leadership and location-specific capabilities and conditions. Majava, Rinkinen, and Harmaakorpi (Citation2020) investigated the business ecosystem perspective on innovation policy based on the San Diego case. Finally, Abremski and Roben (Citation2021) studied how San Diego’s region has benefitted from the presence of military, private and public sector innovation partners.

4. Results

4.1. Innovation ecosystem stakeholders

In the analysis, the ecosystem’s key (i.e. the most influential) stakeholders were categorised as individual and organisational stakeholders. The individual stakeholders included scientists, entrepreneurs, angel investors and local leaders, including the leaders of CONNECT, BIOCOM and other influential organisations as well as the leaders of UCSD, the most influential companies and, to some extent, the city government. The roles of scientists in new inventions and entrepreneurs in innovation commercialisation were stressed in almost all the studies (Appendix 1). The angel investors, also as funders and advisors, were often highlighted too. In addition, local leaders were seen as key individual stakeholders in twelve studies.

Findings on the organisational stakeholders were more diverse. In , rows 1–20 depict which articles stressed each stakeholder, whereas the last row shows how many of the eight experts interviewed highlighted the stakeholder’s role.

Table 3. Innovation ecosystem organisational stakeholders.

As ’s patterns indicate, the roles of the UCSD and research institutes were emphasised unanimously because of their ability to provide new technology and ideas as well as education and training. San Diego began to focus on clean industries in the 1950s, partly because of limited natural resources and remoteness in establishing manufacturing and heavy industries. The establishment of research institutes, especially UCSD, with the aim of research excellence and research – business collaboration, was a significant trigger for the innovation ecosystem’s birth.

The VC firms were also stressed to be critical in shaping the ecosystem’s evolution and expansion; only Lakoff (Citation2008) and Sumikura, Sugai, and Maki (Citation2018) did not emphasise their role. Naturally, pioneer companies, such as Hybritech, and leading companies (e.g. Qualcomm) were also highlighted in most studies. In the 1970s, life sciences funding increased, and Hybritech was founded. After its initial success, Hybritech was acquired by Eli Lilly, which brought new capital into the ecosystem, and many start-ups were created by former employees. Another key event affecting the ecosystem’s evolution was the local business leaders’ decision in the mid-1980s to work with UCSD to develop an innovation-acceleration organisation; CONNECT and other intermediary and trade organisations were seen as key stakeholders in fourteen analysed articles.

shows that earlier studies have focused mainly on UCSD, research institutes, VCs, companies, CONNECT and other intermediaries. As the innovation ecosystem has gained leadership, the role of business services, such as law firms, has become more visible in studies published since 2014. Incubator activities have also increased to support ecosystem self-renewal, and their role has been highlighted in studies published since 2016. Overall, the number of analysed stakeholders increased as San Diego’s innovation ecosystem and related research evolved. Sumikura, Sugai, and Maki (Citation2018) are an exception, focusing mainly on UCSD and research institutes. Interestingly, only Tvedt (Citation2019) considered Baja California an important resource for the innovation ecosystem.

The expert interviews’ results were in line with the findings above. Scientists, entrepreneurs, leaders and angel investors were found to be key individual stakeholders. The angels, for example, have an important role in funding, advising start-ups and refining their business plans. UCSD and the research institutes were considered the key organisational stakeholders, as they acquire research funding, create new technologies and ideas, and train new talent. VCs were found to be critical for supporting companies’ growth in later stages. Pioneer companies, such as Hybritech and Linkabit, were highlighted by only three experts, but they were described as ‘roots of family trees’ in the innovation ecosystem. Leading life sciences companies, large pharmaceutical companies’ presence and Qualcomm were also considered important. Furthermore, CONNECT, especially its Springboard programme, was highlighted as critical for the innovation ecosystem’s evolution. Trade organisations, such as BIOCOM, typically attract more established companies and provide resources, advocacy and local and global networking opportunities. The experts also emphasised the importance of numerous accelerator and incubator organisations and programmes. Business services, such as legal, financial and human resources and real estate, were seen as supporting stakeholders.

4.2. PEST analysis of the success factors

Political, economic, social/cultural and technological (PEST) analysis (Ho Citation2014) was conducted to understand the factors that have contributed to San Diego’s innovation ecosystem success. shows the political and economic factors highlighted in the studies. Regarding political factors, the role of research funding was vital in fourteen studies. Other types of public funding, including small business innovation research (SBIR) and small business technology transfer (STTR), were also found to be important. Overall, government policy was emphasised in ten studies. The geographical proximity of actors and local government land development (zoning decisions) are closely related factors, and their importance is often stressed. Three studies also identified government regulations (e.g. finance and environment) as important. The key economic factors, in turn, included support systems for start-ups as well as acquisitions of start-ups by larger companies and IPOs that provided new capital to the ecosystem. Some studies also emphasised the availability of customers (e.g. hospitals), suitable real estate (laboratories, offices and other facilities), employees’ interfirm mobility and the ecosystem’s ability to attract talented employees outside the region (i.e. career opportunities).

Table 4. Political and economic factors.

The interview results supported these findings. The experts considered reliable funding sources for research and start-ups to be critical. They saw that local, state and federal governments provide the ecosystem with the infrastructure, legislation, regulation and policies that guide research and public funding. Geographical proximity was also highlighted. The experts also stressed start-up support systems, including, for example, advisor networks. The capital gained through acquisitions and IPOs and the ability to attract talent were also important. Two experts mentioned that customers (healthcare providers) were important in clinical trials.

The social and technological factors identified in the studies are shown in . Among the social factors, collaboration and social networks were found to be important in most studies. Five studies emphasised coopetition (i.e. parallel collaboration and competition). Surprisingly, trust was stressed in only four studies. The San Diego region offers residents a high quality of life, which is important for retaining and attracting people, and this was also highlighted. Many researchers also saw the culture of risk-taking, the business climate and local leadership important. Key social factors also included celebrating start-up firms’ success and a bottom-up approach to building the innovation ecosystem. Interestingly, diversity was highlighted only by one study. Regarding technological factors, technology transfer (e.g. patent licensing from UCSD and research institutes) was often highlighted. Many researchers also saw that San Diego has benefitted from focusing on specific technology areas and gaining a critical mass in research and business activities.

Table 5. Social and technological factors.

The interview results complemented the findings. Although trust was not emphasised in the studied articles, six experts stressed its role. Organisations such as CONNECT were found to be important because they provide opportunities for people to meet and strengthen relationships. A culture of collaboration, openness in sharing ideas and helping others were often mentioned. San Diego was considered a place ‘that makes people stay’ and to have a risk-taking and entrepreneurial culture. The experts saw leadership commitment to developing the region as important. Technology transfer from universities and research institutes, critical mass in research, unique focus areas of expertise and diversity were also highlighted.

As the patterns in and indicate, some of the studies are very specialised (e.g. Lakoff Citation2008; Sumikura, Sugai, and Maki Citation2018) and focus on certain PEST factors, whereas the broadest considerations were found in Walshok et al. (Citation2002), Walshok and Shragge (Citation2012), Walshok and Lee (Citation2014), and Majava et al. (Citation2016a, Citation2020). Overall, the number of analysed factors affecting ecosystem dynamics and success increased as San Diego’s innovation ecosystem and related research evolved. By the mid-1990s, San Diego had developed the world’s third-largest biosciences industry after San Francisco and Boston. Since then, the innovation ecosystem has increased its diversity and self-organisation capability, which are important in the leadership and self-renewal phases. Since the 2010s, new opportunities for self-renewal have emerged from the convergence of the life sciences, wireless and IT sectors, and ecosystem dynamics involve constant experimentation, innovation and reinvestment. Besides the cluster viewpoint that was popular in older studies, studies 11–15 have adopted new approaches to analyse San Diego’s evolution, such as the business ecosystem, spatial innovation, network organisations, entrepreneurship, knowledge transfer and organisational learning concepts. Despite different research approaches and times, several factors, such as funding, support systems for start-ups, collaboration and technology transfer, have been found to be important throughout most studies.

5. Discussion

Previous research has addressed several important aspects of San Diego’s innovation ecosystem and how it emerged (Walshok and Shragge Citation2012), including, for example, the roles of universities, pioneer companies, and other institutions (Lakoff Citation2008; Walshok and Lee Citation2014); the importance of social networks and interfirm mobility (Casper Citation2007); and cultural aspects and collaborative learning (Kim Citation2015). The San Diego case illustrates that to drive innovation and growth, ecosystems need high-quality universities and research institutions, research funding, seed and venture capital, pioneer start-ups and leading companies. However, these organisations are built from individuals, that is, researchers, entrepreneurs and leaders, among others. As identified, the innovation ecosystem should provide lucrative career opportunities to attract and retain talented people. Human capital and the presence of companies that provide downstream opportunities are important for success. The roles of leading scientists (Sumikura, Sugai, and Maki Citation2018), pioneer companies and entrepreneurs (Casper Citation2007) are also stressed.

Venture capital has been seen crucial for innovation ecosystem success (e.g. Powell et al. Citation2002), but funding needs may vary across different phases. For high-tech innovation in San Diego, funding was needed for basic and applied research, start-ups needed seed and growth funding from private and public sources; in addition, access to long-term capital was also needed. Angel investors were particularly vital in the early start-up stage, not only in providing funding, but also in providing guidance. Successful matchmaking between scientists, entrepreneurs and investors was essential. Appropriate support systems for start-ups were also needed – San Diego’s CONNECT model exemplified an interesting matchmaking and support model. At later stages, companies also needed larger funding, so gaining access to both local venture capital and VCs in other locations (e.g. the San Francisco Bay area) was important.

Previous research has suggested that innovation processes and learning require different forms of proximity as well as sufficient distance, here depending on the process stage (Balland, Boschma, and Frenken Citation2015). San Diego’s identified success factors include collaboration (fostered by geographical proximity) and social networks, which indicate social proximity between ecosystem actors, whereas acquisitions and interfirm mobility increase organisational proximity. The ability to attract talent outside the ecosystem is an example of the importance of the needed distance. In addition, the roles of stakeholders and factors may vary during ecosystem evolution, reflecting the different resources needed in different phases (Liu et al. Citation2022). Besides learning from the past, communities may need transformative learning skills (Mezirow Citation2018), such as collective imagination and embracing uncertainty, to move to the next phase. As identified in the current study, public actors can contribute to the ecosystem’s success via policy, legislation, regulation, infrastructure and research funding decisions. Furthermore, research- and technology-intensive sectors also require defining unique focus areas by utilising, for example, smart specialisation strategies. Moreover, critical mass in selected research areas, idea generation, diversity and rapid technology transfer from universities and research institutes should be ensured.

Our study shows that San Diego succeeded despite its original disadvantages until the mid-1980s, including a lack of local VCs and large company headquarters, an image of ‘a small military town’, a high cost of living, land and real estate and intense competition from other states. Some weaknesses, such as a small airport and high labour costs, have been alleviated via connections to Los Angeles and Tijuana (Baja California). Although our study is not comparative, it should be noted that, in addition to San Diego, other cities, such as Austin and Texas (Gibson and Oden Citation2019), can also provide interesting insights. Austin and San Diego differ in their technology focus areas but are similar in size, have world-class universities and are rather remote from larger cities, that is, Dallas and Los Angeles. However, differences, for example, in demographics, also exist that affect the social network characteristics of ecosystems.

6. Conclusion

This systematic literature review of San Diego’s innovation ecosystem provides both researchers and decision makers with a deep understanding of the stakeholders and factors that have influenced the ecosystem’s dynamics and evolution, complementing earlier case studies and expert interviews. Additionally, the study offers an example of a relatively remote city’s path to success, providing innovation policy insights for nonleading regions. Today’s sustainability challenges are solved not only by investing in new global technologies, but also by developing and promoting rapid local solutions, where regional innovation ecosystems play a major role. For regional innovation research, this study methodologically exemplifies how to systemically analyse an innovation ecosystem’s development instead of using a case study approach.

Although a systematic literature review complemented by expert interviews can provide valid and reliable results, focusing solely on San Diego’s innovation ecosystem limits its generalizability. The innovation ecosystem stakeholders and success factors also depend on local conditions. For example, Casper (Citation2014) argued that San Diego’s biotechnology sector developed from a different interaction pattern between the university and businesses than that in San Francisco. The geographical concentration of research organisations, biotechnology firms, and VCs is often very strong; however, especially in the 1970s and early 1980s, San Diego lacked local venture capital, and university – business cooperation was also less common. The findings on San Diego are less in line with the wide research on the Silicon Valley area (e.g. Kenney Citation2000). The key networks in San Diego are entrepreneurial and largely based on business-focused managers and researchers with backgrounds at the pioneer company Hybritech (Casper Citation2014). This indicates that each location must utilise its unique strengths in its development path.

Although successful innovation ecosystems are built on many resources and features that are not directly amplifiable elsewhere, their success is often also associated with replicable factors (Etzkowitz Citation2019), many of which were validated by this study. The evolution of innovation research during the time the San Diego case has been studied should also be noted. Although the ecosystem concept considers a broad spectrum of factors, actors and relations that influence innovation activities, the reviewed studies also used other theoretical approaches. Development within regional innovation research may influence which stakeholders and success factors were emphasised or considered in each study. The studies also differed in scope and may have focused on different stakeholders and factors, for example, because of the funders’ requirements. However, this can also be seen as the benefit of the chosen review method: the possibility of analysing research conducted from different viewpoints and at different times to provide an in-depth understanding of the studied case.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the interviewees, editors and anonymous referees for their valuable contribution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jukka Majava

Jukka Majava received his D.Sc. (Tech.) degree from University of Oulu in 2014. His research interests include innovation management, operations management, sustainability, and digitalisation.

Satu Rinkinen

Satu Rinkinen received her D.Sc. (Tech.) degree from LUT University in 2016. Her research interests include innovation policy, innovation-based regional renewal, and sustainable regional development.

References

- Abremski, D., and P. Roben. 2021. “UC San Diego, The Military and Building a Unique, Diversified Economic Growth Ecosystem.” Journal of Commercial Biotechnology 26 (1): 93–101. doi:10.5912/jcb974

- Balland, P. A., R. Boschma, and K. Frenken. 2015. “Proximity and Innovation: From Statics to Dynamics.” Regional Studies 49 (6): 907–920. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.883598

- Casper, S. 2007. “How do Technology Clusters Emerge and Become Sustainable?: Social Network Formation and Inter-Firm Mobility Within the San Diego Biotechnology Cluster.” Research Policy 36 (4): 438–455.

- Casper, S. 2014. “The University of California and the Evolution of the Biotechnology Industry in San Diego and the San Francisco Bay Area.” In Public Universities and Regional Growth: Insights from the University of California, edited by M. Kenney and D. Mowery, 66–96. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Cooke, P. 2006. “Global Bioregions: Knowledge Domains, Capabilities and Innovation System Networks.” Industry and Innovation 13 (4): 437–458. doi:10.1080/13662710601032812

- Etzkowitz, H. 2019. “Is Silicon Valley a Global Model or Unique Anomaly?” Industry and Higher Education 33 (2): 83–95. doi:10.1177/0950422218817734

- Gibson, D., and M. Oden. 2019. “The Launch and Evolution of a Technology-Based Economy: The Case of Austin Texas.” Growth and Change 50 (3): 947–968.

- Granstrand, O., and M. Holgersson. 2020. “Innovation Ecosystems: A Conceptual Review and a new Definition.” Technovation 90: 102098. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2019.102098

- Ho, J. K. K. 2014. “Formulation of a Systemic PEST Analysis for Strategic Analysis.” European Academic Research 2 (5): 6478–6492.

- Kenney, M. ed. 2000. Understanding Silicon Valley: The Anatomy of an Entrepreneurial Region. Stanford University Press.

- Kim, S. T. 2015. “Regional Advantage of Cluster Development: A Case Study of the San Diego Biotechnology Cluster.” European Planning Studies 23 (2): 238–261. doi:10.1080/09654313.2013.861807

- Kim, S. T., and M. G. Jeong. 2014. “Discovering the Genesis and Role of an Intermediate Organization in an Industrial Cluster: Focusing on CONNECT of San Diego.” International Review of Public Administration 19 (2): 143–159. doi:10.1080/12294659.2014.915474

- Lakoff, S. 2008. “Upstart Startup: “Constructed Advantage” and the Example of Qualcomm.” Technovation 28 (12): 831–837. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2008.07.001

- Liu, J., H. Zhou, F. Chen, and J. Yu. 2022. “The Coevolution of Innovation Ecosystems and the Strategic Growth Paths of Knowledge-Intensive Enterprises: The Case of China’s Integrated Circuit Design Industry.” Journal of Business Research 144: 428–439. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.02.008

- Majava, J., T. Kinnunen, D. Foit, and P. Kess. 2016b. “An Intermediary as a Trust Enabler in a Spatial Business Ecosystem.” International Journal of Innovation and Learning 20 (2): 199–213. doi:10.1504/IJIL.2016.077845

- Majava, J., T. Kinnunen, D. Foit, and P. Kess. 2017. “Analysing Innovation-Driven Enterprises’ Stakeholders in two Spatial ICT Ecosystems.” International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development 16 (3): 207–220. doi:10.1504/IJMED.2017.085041

- Majava, J., P. Leviäkangas, T. Kinnunen, P. Kess, and D. Foit. 2016a. “Spatial Health and Life Sciences Business Ecosystem: A Case Study of San Diego.” European Journal of Innovation Management 19 (1): 26–46. doi:10.1108/EJIM-01-2015-0003

- Majava, J., S. Rinkinen, and V. Harmaakorpi. 2020. “Business Ecosystem Perspective on Innovation Policy: A Case Study of San Diego Life Sciences.” International Journal of Innovation and Learning 27 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1504/IJIL.2020.103886

- Mezirow, J. 2018. “Transformative Learning Theory.” In Contemporary Theories of Learning, edited by K. Illeris, 114–128. Routledge.

- Powell, W. W., K. W. Koput, J. I. Bowie, and L. Smith-Doerr. 2002. “The Spatial Clustering of Science and Capital: Accounting for Biotech Firm-Venture Capital Relationships.” Regional Studies 36 (3): 291–305. doi:10.1080/00343400220122089

- Sable, M. 2007. “The Impact of the Biotechnology Industry on Local Economic Development in the Boston and San Diego Metropolitan Areas.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74 (1): 36–60. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2006.05.016

- Steward, F. 2012. “Transformative Innovation Policy to Meet the Challenge of Climate Change: Sociotechnical Networks Aligned with Consumption and end-use as new Transition Arenas for a low-Carbon Society or Green Economy.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 24 (4): 331–343. doi:10.1080/09537325.2012.663959

- Sumikura, K., N. Sugai, and K. Maki. 2018. “The Involvement of San Diego-Based Star Scientists in Firm Activities.” 2018 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), 1-8, IEEE.

- Tvedt, H. L. 2019. “The Formation and Structure of Cleantech Clusters: Insights from San Diego, Dublin, and Graz.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift-Norwegian Journal of Geography 73 (1): 53–64. doi:10.1080/00291951.2019.1568295

- Valkokari, K. 2015. “Business, Innovation, and Knowledge Ecosystems: How They Differ and how to Survive and Thrive Within Them.” Technology Innovation Management Review 5 (8): 17–24. doi:10.22215/timreview/919

- Walcott, S. 2001. “Growing Global: Learning Locations in the Life Sciences.” Growth and Change 32 (4): 511–532. doi:10.1111/0017-4815.00173

- Walcott, S. M. 2002. “Analyzing an Innovative Environment: San Diego as a Bioscience Beachhead.” Economic Development Quarterly 16 (2): 99–114. doi:10.1177/0891242402016002001

- Walshok, M. L., E. Furtek, C. W. B. Lee, and P. H. Windham. 2002. “Building Regional Innovation Capacity: The San Diego Experience.” Industry and Higher Education 16 (1): 27–42. doi:10.5367/000000002101296063

- Walshok, M., and C. Lee. 2014. “The Partnership Between Entrepreneurial Science and Entrepreneurial Business: A Study of Integrated Development at UCSD and San Diego’s High-Tech Economy.” In Building Technology Transfer Within Research Universities: An Entrepreneurial Approach, edited by T. J. Allen, and R. P. O’Shea, 129–153. Cambridge University Press.

- Walshok, M. L., and A. J. Shragge. 2012. “The Invention of San Diego’s Innovation Economy.” In Creating Competitiveness: Entrepreneurship and Innovation Policies for Growth, edited by D. B. Audretsch and M. L. Walshok, 186–210. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Walshok, M., and A. Shragge. 2014. Invention and Reinvention: The Evolution of San Diego’s Innovation Economy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Williams, M. D. 2005. “Measuring the Impact of Technological Innovation on Sustainable Development in San Diego.” World Review of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development 2 (1): 11–34. doi:10.1504/WRSTSD.2005.006725

- Xiao, Y., and M. Watson. 2019. “Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 39 (1): 93–112. doi:10.1177/0739456X17723971

- Youtie, J., R. Ward, P. Shapira, R. S. Schillo, and E. Louise Earl. 2021. “Exploring new Approaches to Understanding Innovation Ecosystems.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 35 (3): 255–269.