ABSTRACT

More than ten years after the global financial crisis, what has happened to the ‘too-big-to-fail’ (TBTF) banks whose reckless behavior was among its preconditions, but which received public support and guarantees in the midst of that crisis? Insofar as this too-big-to-fail status helped create the crisis and then imposed costs on the rest of society, we would expect these banks to have shrunk. We investigate the evolution of 31 global-TBTF banks and find that their overall size has hardly recorded any substantial change. However, there is no sense of urgency in the flourishing post-crisis literature on TBTF banks about the need to contain their size; the prevalent view therein is that if properly regulated, the risks that arise from a financial system dominated by TBTF banks are manageable. This view rests on the same overly narrow theoretical underpinnings whose flaws were exposed in the crisis. We argue that too-big-to-fail banking is embedded in a set of self-reinforcing policies—consolidation, balance-sheet support through quantitative easing, favorable regulations, bank lobbying, and geo-economic and geo-political considerations—which explain why these banks have not shrunk and why they remain a threat to financial stability, well after the lessons of the crisis should have been learned.

1. Introduction

If one could journey back in time to late 2008 and ask people what changes were needed in the financial system, the shrinking of the largest financial institutions that had brought the global economic system to the brink of collapse would be on the top of the list. The 10th anniversary of Lehman Brothers' bankruptcy (at the time of writing) makes this an opportune time for a reality check. This paper examines whether megabanks have shrunk post-crisis, focusing on 31 banks classified as global systemically important by the Financial Stability Board (FSB Citation2017, Citation2018). We find that some shifts in size related to strategic adjustments have occurred amongst this sample of banks; but taken as a whole, the change in size is negligible, with aggregate figures still accounting for disproportionately large shares of GDP. This leads to a further question: what explains the post-crisis persistence of too-big-to-fail (TBTF) banking, and what risks does it pose?

A flourishing literature on TBTF banks has arisen post-crisis: whereas the term ‘too-big-to-fail’ appeared as a Web of Science topic word just nine times in economics/finance journal articles or chapters published between 1990 and 1997 and 44 times between 1999 and 2009, it was selected as a topic word 369 times between 2010 and 2018. But, with the notable exception of Schoenmaker (Citation2017), this post-crisis literature pays little attention to the question of why these banks have not shrunk; it focuses instead on whether efficiency benefits justify their size, and on how appropriate regulation can reduce any adverse spillovers.

We consider this largely overlooked question of the stable post-crisis size of TBTF banks. We do so via a political economy prism that links post-crisis micro level developments (banking consolidations) to the macro level (quantitative easing monetary policies and regulation), the issue of power (bank lobbying), and geo-economic and geo-political structures (the unique role of the US dollar and of global finance in the world economy). This effort at bringing these multi-level, multi-site aspects of TBTF banks into one analytical framework is necessarily exploratory, an initial analysis of the forces at play. For these banks are not simply the largest members of an economic subsystem that channels funds from entities with surplus funds to those requiring funds (as in Mishkin Citation2007). Instead, TBTF banks and the financial ecosystems that surround them comprise complex systems that have been embedded in particular geo-economic circumstances for decades (Walby Citation2009; Ingham Citation2013). Arguably, the persistence of the outsized scale of TBTF banks post-crisis has escaped notice precisely because of these two-way relationships with national and global systems of markets and regulation. The effect is to shape our thinking about the inevitability of these institutions’ centrality in the economy to such an extent that their power is hidden in plain sight.

We proceed as follows. Section Two defines TBTF banks and provides a short history that traces their evolution through the 2007–2008 financial crisis. Section Three identifies the banks on which we focus and reviews summary data about their recent development. Section Four then contrasts the post-crisis analyses of financial policy-makers and of equilibrium-based economists regarding the future of TBTF banks. Section Five develops an alternative analysis by mapping out the political economy of too-big-to-fail banking. In effect, these institutions are sustained by a set of interconnected, self-reinforcing factors, whose ability to deflect change may be generating the pre-conditions for another meltdown. Section Six draws some tentative conclusions and suggests directions for future research.

2. ‘Too-Big-To-Fail’ Banks: A Definition and A Short History

A financial institution becomes ‘too-big-to-fail’ when it grows so large that its failure threatens the integrity of the financial system and of the national economy in which that system is embedded. Because of its systemic importance, any threat of a TBTF bank’s failure will be forestalled by public action, no matter the consequences for the government undertaking this rescue. Both excessive institutional size and threat of failure are implicit in the term too-big-to-fail: indeed, the term as such connotes a double-sided threat.

Most importantly, this is a threat that can neither be proven or refuted ex-post, as the only way of doing so would be by allowing a too-big-to-fail institution to collapse and letting all consequences play out in full. The impossibility of gathering objective evidence either supporting or undercutting the credibility of the too-big-to-fail threat, together with recurrent instances of large bank insolvency, has made it a perennial issue in the chronicles of finance and capitalism.

For advocates of laissez faire banking, the too-big-to-fail status of large banks poses a fundamental threat to financial market discipline. In its most extreme form, this argument suggests that permitting the failure of a bank presumed to have this status would actually rejuvenate the financial market; Moosa (Citation2010) for example argues that removal of too-big-to-fail protection would reduce moral hazard distortions in financial markets, discourage the rent-seeking lobbying of regulators and legislators, and free taxpayer money for other purposes, such as job creation.Footnote1 Policy-makers charged with maintaining financial stability however, have seldom, if ever, been willing to see whether allowing a TBTF bank to fail would indeed benefit the functioning of the financial market or instead lead to a cataclysmic collapse.

The history of public interventions motivated by fear of the catastrophic consequences of large enterprises’ failure is almost as old as that of corporations. For example, in the mid-eighteenth century, drought and conflict in India sank the share price of the British East India Company, restricting its access to credit and putting it on the brink of collapse. The Company was so central to British commercial and imperial interests that the government arranged a bailout. The resulting hole in British government finances led to increased taxation of the American colonies, one of the central causes of the American War of Independence (see Frankopan Citation2015).

The contemporary use of the term ‘too-big-to-fail’ has American roots. The first use occurred in 1984, after a Congressional hearing about the seizure of the insolvent Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust, the seventh-largest bank in the United States, by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (Dymski Citation2011). The inability of the Federal Reserve to find a buyer for Continental, which had experienced ‘a high-speed electronic bank run’ in May 1984 raised questions about the stability of the US financial system; John Conover, US Comptroller of the Currency, designated 11 US banks, including the US’s eight ‘money center banks’ as ‘too-big-to-fail’ so as to head off further bank runs (FDIC Citation1997). This broader designation, it should be noted, also provided protection against adverse market reactions to extensive losses of these banks on Latin American loans. Between 1991 and 2004, amidst a broad-based consolidation wave in US banking, seven of these institutions were absorbed by other four on Conover’s list (Dymski Citation2011).

The problem with designating institutions as ‘too-big-to-fail,’ the step taken by Conover, was that this both enhanced their market value and created a new source of moral hazard in US banking (see O’ Hara and Shaw Citation1990). Regardless of misgivings about encouraging excessive risk-taking, this concept was further embedded in the US regulatory framework. For example, 1991 legislation, which sought to reduce moral hazard due to deposit insurance, set out procedures for too-big-to-fail interventions (rather than declaring them illegal; Dymski Citation2011). The passage of the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which eliminated the Glass-Steagall Act division between investment and commercial banking, was shortly followed by an article in the Federal Reserve Bulletin expressing concerns about the increasing share of banking assets held by ‘large complex banking organizations’ (LCBOs) in the US system (see DeFerrari and Palmer Citation2001). Three years later, a Brookings Institution study warned that 34 LCBOs (19 US-based, 15 foreign) could be classified as TBTF (see Stern and Feldman Citation2004, p. 39).Footnote2

The presence of non-US banks on the Brookings list highlights the fact that many national economies across the world include very large banks whose failure would compromise their economic growth and financial coherence. In UK banking, deposit and asset totals are dominated by clearing banks, whose founding dates to 1775, a period in which the British economy was being structured to manage a global colonial empire. In the 1960s, these banks began to expand their global reach and undertake mergers and acquisitions. When permission was granted for mergers between clearing banks, the sector consolidated rapidly (Maycock Citation1986). The population of UK clearing banks shrunk from 16 in 1960 to 4 at present (Davies et al. Citation2010). Furthermore, a number of countries—including Japan, Germany, and France—rely on very large banks as the hubs of ‘bank-based’ systems for providing capital and credit flows to non-financial firms (Zysman Citation2003).

Size has been a continuing feature of many financial systems in the US and Europe. The ‘threat’ component necessary for converting merely large banks into too-big-to-fail institutions emerged in the 1980s and 1990s. Widespread financial deregulation led to many large non-US banks shifting from public to private ownership and entering the emerging global markets for securities and derivatives. The ‘single market’ goal adopted in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, in turn, led several European nations to oversee defensive bank mergers aimed at creating national banking ‘champions’ that could better compete with foreign competitors (Dymski Citation2002).

The full threat potential of a global financial system with a growing population of TBTF banks was demonstrated dramatically on 15 September 2008 when the insolvent Lehman Brothers, one of the five largest US investment banks, filed for bankruptcy after a fruitless search for a willing buyer. While Lehman had not been tagged as too-big-to-fail in either the Conover or Brookings lists, its failure sent financial markets tumbling and brought US and global financial markets to the brink of collapse. By September 21, both Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, the two largest remaining US investment banks, were classified as bank holding companies and thus given TBTF protection—despite the fact that both were technically insolvent. On 13 October, US Treasury Secretary Paulson offered new capital and government guarantees—effectively a bail out—to nine major banks (Johnson and Kwak Citation2010). Numerous bailouts of banks and non-bank intermediaries followed, in the US and around the world. As Johnson and Kwak (Citation2010, p. 164) put it, ‘never before has so much taxpayer money been dedicated to save an industry from the consequences of its own mistakes’.

3. Too-Big-To-Fail Banks: Some Stylized Facts

We focus here on the 31 institutions classified as global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) by the Financial Stability Board (FSB, or the Board).Footnote3 All but two of these 31 banks appear on the most recent (November 2018) list provided by the FSB (Citation2018). The two banks we add to that list, Royal Bank of Scotland and Nordea, were named on the FSB’s first listing of global-systemically important institutions in 2011, and were consistently listed up until 2017 (see FSB Citation2017) ().Footnote4

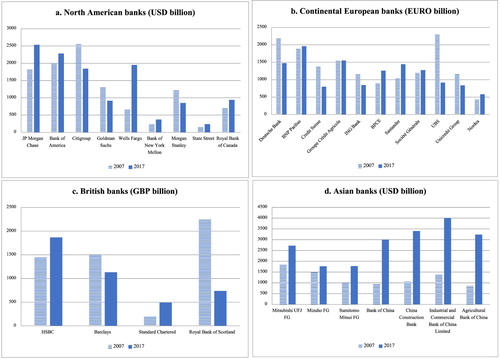

Figure 1. Change in the size of Too-Big-To-Fail banks, 2007–2017. Notes: 2007 figures have been adjusted for inflation.

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence, OECD and authors' calculations.

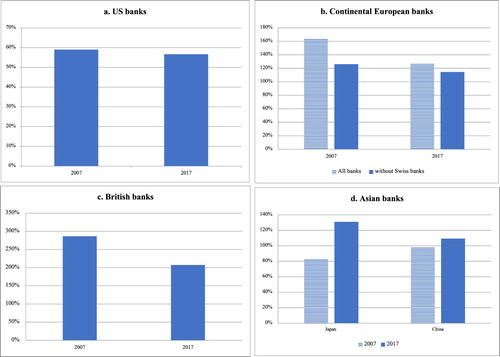

Figure 2. Change in size of Too-Big-To-Fail banks, measured as a proportion of GDP of the home country, 2007–2017. Notes: the graph for continental Europe uses the sum of GDP of the following countries as a denominator: France, Germany, Spain, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland (only when Swiss banks are included) and Netherlands; Royal Bank of Canada has been omitted in this graph.

Sources: S&P Global Market Intelligence, OECD and authors' calculations.

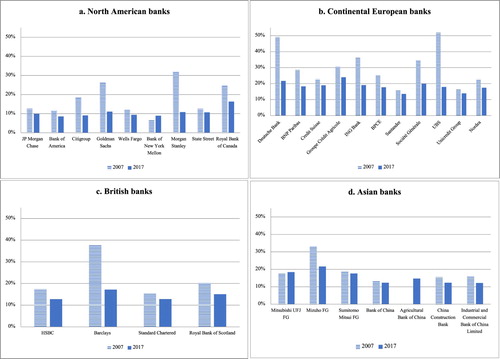

Figure 3. Change in leverage ratios of Too-Big-To-Fail banks, 2007–2017. Notes: Leverage ratio measured as Total Assets/ Total Equity; due to differences in its accounting standards between 2007 and 2017, the 2007 leverage ratio for the Agricultural Bank of China appears as negative, and is therefore omitted here.

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence.

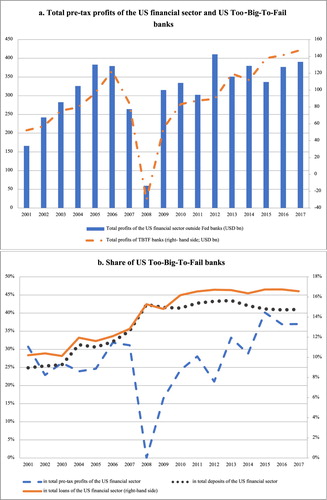

Figure 4. Profits and concentration in the US financial sector, 2001–2017. Notes: Fed banks not included.

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence, Federal Reserve, US Bureau of Economic Analysis and authors' calculations.

The Board identifies G-SIBs as requiring special regulatory attention due to the ‘systemic and moral hazard risks’ they pose. Its list and criteria for inclusion are updated annually, considering such factors as size, interconnectedness, and global presence among others. Since 2012, listed G-SIBs have been sorted into risk buckets, from 1 to 5 (lower to higher risk). These buckets specify the ‘required level of additional common equity loss absorbency as a percentage of risk-weighted assets’ (FSB Citation2018) for each listed bank.Footnote5 Banks in the lowest bucket should maintain a capital/asset ratio 1 per cent higher than required by their national authorities. This capital/asset increment is raised by an extra 0.5 per cent per bucket, for banks in buckets 2–4. An additional 1 per cent is then mandated for any bank classified in to the top risk tier, a bucket that is intentionally left empty to permit the tightening of capital requirements for any listed bank whose riskiness might push it past the bucket-4 ceiling.

As listed by the FSB in 2018, the top 10 banks come from five countries: four from the US (JP Morgan, Bank of America, Citigroup and Goldman Sachs), two from the UK (HSBC and Barclays), two from China (Bank of China and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China), and one each from France (BNP Paribas) and Germany (Deutsche Bank). Other countries with banks on the list are Japan, Switzerland, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and Canada.

It is useful to present a panoramic view of the post-crisis changes in asset size of the 31 TBTF banks. To this end we contrast data from 2017 with data from 2007, the year immediately preceding the Lehman collapse. As shows, five out of eight US megabanks have grown in size, while three—Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley—have become smaller. On the other side of the Atlantic, five megabanks in continental Europe have grown and five have shrunk, with Crédit Agricole maintaining its pre-crisis size. The two Swiss banks, Credit Suisse and UBS, have declined in size most dramatically, a phenomenon largely explained by tightened regulation of the Swiss financial sector (also see discussion below). British banks exhibit moderate change, with the exception of RBS, which has shrunk to less than half of its 2007 size. On the other hand, Japanese and Chinese banks have grown significantly. The resilience of Asian banking to the crisis and the Japanese leadership in the investment banking sector help explain this development (Wójcik et al. Citation2018).

provides a complementary picture for these same geographic areas, showing TBTF banks’ aggregate asset size as a share of GDP. As (a) illustrates, the ratio for the US megabanks has hardly recorded any significant change, moving from 59 per cent of US GDP in 2007 to 57 per cent in 2017. A more notable decline is registered in continental Europe, where the combined size of TBTF banks has fell from 164 per cent to 127 per cent of the relevant countries’ summed GDP totals. As shown in (b) this is largely due to the decline of Swiss banking. UK megabanks’ share of British GDP has recorded a steep fall due to the shrinkage of RBS. Nonetheless, these banks still account for a disproportionately large share of British GDP, more than 200 per cent. Japanese banks have grown more than any, jumping from 82 per cent of Japanese GDP in 2007 to 129 per cent in 2017. Chinese banks have also grown, very much in line with the growth of the Chinese economy. Their combined asset size currently exceeds 100 per cent of the China’s GDP.

The capitalization of almost all TBTF banks has improved since the crisis. In 2008–2010, this was due almost entirely to injections of capital from governments (Tooze Citation2018, ch 7). National governments in the US and Europe committed $679 billion to their banks’ recapitalization, of which $338 billion was taken up (at the cost of widening budget deficits); these injections were supplemented by numerous liability-guarantee and asset-support programs, the total of which amounted to significant percentages (typically 33–50 per cent) of these nations’ 2008 GDP levels (see Stolz and Wedow Citation2010, Table 1). These efforts and many banks’ efforts to raise capital in markets were undertaken under sustained pressure from the FSB and other regulatory bodies to increase capital and undertake consolidation (see discussion below). illustrates the change in the capitalization of TBTF banks by reporting their leverage ratios. With the exception of Bank of New York Melon which had the lowest leverage ratio of all 26 banks in 2007, and Mitsubishi which has recorded a very mild growth, all other banks exhibit a uniform decreasing trend. In the US, the steepest declines are recorded for the two big investment banks, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. In Britain and continental Europe, Deutsche Bank, UBS and Barclays exhibit the biggest drops.

Given their centrality in global finance and their role as protagonists in the events leading to the financial crisis of 2007/08, US megabanks deserve closer examination. To this end, (a) illustrates the fluctuations of the pre-tax profits of these banks, and their correlation with the aggregate pre-tax profits of the entire US financial sector (outside Fed banks). There are two striking findings. First, there is a sharp V-shape pattern in the profits of the eight US megabanks. These profits have not only recovered from the crisis but are nowadays reaching record highs. The same holds for the aggregate US financial sector. This brings us to the second observation. After adjusting the two scales, a strong correlation (81 per cent) between TBTF banks’ profits and aggregate financial profits can be identified in (a). This holds both pre- and post-crisis. Such correlation indicates that the volatility emanating from TBTF banks is fully transmitted to the aggregate level rather than being absorbed elsewhere in the system.

The continuing strength of this co-movement in profits is indicative of the persistence of the too-big-to-fail issue. To shed further light, (b) presents evidence on the increasing concentration of the US financial sector. The share of TBTF banks in the total profits of the sector has grown from 31 per cent in 2007 to 37 per cent in 2017. Their share in the total volume of deposits has increased from 25 per cent to 41 per cent. For loans their share rose from 10 per cent to 17 per cent.

Overall, these data show that despite the post-crisis identification of too-big-to-fail as a policy concern by financial regulators, megabanks in the US and elsewhere have largely managed to maintain their size and positioning in the broader economy. The next two sections explore two different ways of understanding this seeming anomaly.

4. Regulatory Ambivalence and the Neoclassical Approach to Too-Big-To-Fail Banking

Official national and international inquiries into the global financial crisis invariably recognized bank size as one of the principal causes of the crisis (see FCIC Citation2011; ICB Citation2011; Liikanen et al. Citation2012; BIS Citation2013; FSB Citation2013). For example, a 2013 Bank for International Settlements (BIS) report stated:

A bank’s distress or failure is more likely to damage the global economy or financial markets if its activities comprise a large share of global activity. The larger the bank, the more difficult it is for its activities to be quickly replaced by other banks and therefore the greater the chance that its distress or failure would cause disruption to the financial markets in which it operates. The distress or failure of a large bank is also more likely to damage confidence in the financial system as a whole. Size is therefore a key measure of systemic importance. (BIS Citation2013, p. 7)

While pursuing these key objectives related to financial stability, separation also aims to maintain banks’ ability efficiently to provide a wide range of financial services to their customers. For this reason, the separation is allowed within the banking group, so that the same marketing organisation can be used to meet the various customer needs. Benefits to the customer from a diversity of business lines can therefore be maintained (Liikanen et al. Citation2012, p. vii).

A reflection by Adair Turner, a significant participant in post-crisis financial-policy processes, and one of the most vocal critics of the pre-crisis banking business model, further illustrates the hesitant nature of the regulatory response, and points to a key basis for the ambivalence about addressing the size of TBTF banks. Turner writes:

Overall therefore, I am arguing for a radical reassessment of the too simplistic case in favour of financial liberalisation and financial deepening which strongly influenced official policy in the decades ahead of the crises, and which reflected the dominant conventional wisdoms of neoclassical economics (Turner Citation2010, p. 43).

It is not acceptable that tax payers have to bail out large failing banks, and the ex-ante expectation that they will undermines market discipline. In the latest crisis as in previous ones, however, direct taxpayer costs of bank rescue are likely to account for only a very small proportion of the total economic costs.

Turner’s wish to supersede the ‘conventional wisdom of neoclassical economics’ does not lead him to argue for cutting TBTF banks down in size; to the contrary, he concludes that replacing TBTF banks by a large number of smaller banks would not be desirable. The apparent inconsistency between Turner’s intention and his conclusion lies in the tension between aggregate and micro-foundational approaches to banking, on both of which he draws. Neoclassical support for financial liberalization and the benefits of financial deepening rests on very general theoretical claims about financial intermediation –the idea that having more financial intermediaries permits the financing of more investment, directly or indirectly—and on macroeconometric evidence using aggregate economic variables. From this point of view, Turner’s skepticism about this ‘conventional wisdom’ is well-founded, in that recent econometric evidence has indeed suggested that the finance-growth relationship can turn negative (see for instance Cecchetti and Kharroubi Citation2012).

Turner’s argument against small banks, however, turns on the twin micro-foundational assumptions of neoclassical economics about financial intermediation: first, that TBTF banks may be more operationally efficient than smaller ones, in either static or dynamic terms; second, that TBTF banks can be adequately regulated, in particular by higher capital-to-asset ratios. This logic is similar to that of the Liikanen and Vickers reports and therefore deserves a brief elaboration.

The principal reason for the focus of neoclassical theory on economic efficiency is that this is precisely what is understood as the primary issue at stake. Fama (Citation1980) sets out the definitive neoclassical framework: he shows that in competitive financial markets populated by rational agents, banks’ raison d’être is simply to improve efficiency. In particular, banks may be able to reduce transaction or information costs by taking advantage of economies of scale. The two most influential microfoundational models of banking build on this framework: in the ‘delegated monitoring’ model, banks exist because they can exploit economies of scale in the costs of contract enforcement (Diamond Citation1984); in the ‘liquidity pooling’ model, banks use the law of large numbers to expand illiquid credit commitments without compromising the access to liquidity of depositors facing stochastic shocks (Diamond and Dybvig Citation1983).

The advocacy of megabanks as efficiency-enhancing institutions is a mere extension of the above logic. In the delegated monitoring model, big banks are meant to enjoy economies of scale in their operations, e.g. due to cost-saving technologies. Equally, under the logic of the liquidity pooling model big banks are to achieve better diversified asset portfolios, thereby helping savers insure against their liquidity risk while maximizing the financing of investment. Ultimately, these arguments are based on the idea that market discipline ensures that banks will not deviate from their assigned roles. The term ‘market discipline’ appears repeatedly in both the Vickers and the Liikanen reports; in the Vickers report, for example, the belief in the disciplining forces of the market is emphatically stated in page 1 of the executive summary. These theoretical explanations for why banks exist suggest that the larger the bank, the more efficiently they conduct core banking activities.

So, either implicitly, as in the abovementioned reports and commentaries, or explicitly, as for instance in Elliott (Citation2015), this logic provides a powerful point of departure for post-crisis regulatory debate. Nonetheless, on closer examination some holes appear in this efficiency perspective. It is easy to find individual empirical studies claiming that TBTF banks are the most efficient of all (see for instance Hughes and Mester Citation2013; Beccalli, Anolli, and Borello Citation2015; Kozubovska Citation2017); however, it is also easy to find counter-studies showing that there is a size threshold, no more than $100 billion in assets, beyond which the supposed economies of scale are exhausted (Goldstein and Véron Citation2011; De la Mano Citation2015). Further, measuring economies of scale in banking is an imprecise exercise: identifying the return to specific lines of business, how differences in risk-taking may affect output, whether a bank’s equity or its assets should constitute the denominator, controlling for the level of liability costs, and so on, all are problematic (Dymski Citation1999).

And in any event, emerging financial technologies are eroding the advantages of large banks, as smaller banks and financial technology firms are increasingly able to satisfy global demand for transactions and finance through their syndicates, networks and online platforms (Cassis and Wójcik Citation2018). It can even be argued that large businesses that rely on the services of one large bank, instead of working with multiple banks that have expertise in particular markets and geographies, are defying elementary business logic (De la Mano Citation2015).

Well before the subprime crisis, the implicit subsidies and operating advantages of too-big-to-fail status were integrated into banking-industry dynamics. Achieving too-big-to-fail status became an important motivation for US and European bank mergers (De Young, Evanoff, and Molyneux Citation2009). Indeed, a study of the merger boom years of 1991–2004 found that banks were willing to pay a premium for acquisitions that would make them too-big-to-fail (see Brewer and Jagtiani Citation2013).

The effects of TBTF banks on systemic risks were not unknown; but in the pre-crisis period, they were dismissed. In an overview article on financial consolidation published in 1999, Fredric Mishkin acknowledged the moral hazard problem—that is, the incentives for excessive risk-taking by institutions positioned to escape the consequences of such behavior—but discounted its importance: while consolidation would lead to larger institutions creating ‘increased systemic risk, these dangers can be handled by vigilant supervision and a government safety net with an appropriate amount of constructive ambiguity’ (Mishkin Citation1999, p. 675).

What this view overlooked was the malleability of investor and regulatory sentiment in a business fundamentally underpinned by forward-looking expectations. Mishkin, in focusing on moral hazard, follows the convention of neoclassical economic theory, wherein the preferred analysis is one that deviates as little as possible from the conditions required for Walrasian general equilibrium. In the pre-crisis world, moral hazard problems built into too-big-to-fail status were sufficient to explain banking crises; it was not necessary to complicate models by exploring the banking system’s endogenous tendencies toward instability.

The 2008 financial crash necessitated a sober reassessment of what had gone wrong. For economists working within the neoclassical framework though, that reassessment did not explore the endogenous emergence of financial instability, a process long studied by Hyman Minsky and other Post Keynesian authors (see Minsky Citation1992). Instead it re-emphasized moral hazard-based examinations of whether regulators’ efforts at constructive ambiguity had succeeded or failed.

In a representative assessment, Carow, Kane, and Narayanan (Citation2011) find that these efforts failed. They provide evidence that megabanks’ implicit too-big-to-fail protection led to taxpayer loses exceeding bank customer gains: potential efficiency gains from late-1990s deregulation legislation were more than offset by losses that they trace to banks’ enhanced bargaining power and to their greater access to the federal safety net (Carow, Kane, and Narayanan Citation2011). Post-crisis studies by the Bank of England, reported in a speech by Haldane (Citation2012), reveal the extent of this advantage: too-big-to-fail status provided the world’s largest banks with a subsidy of approximately $70 billion per year during the 2002–2007 period—a figure equivalent to half these banks’ post-tax profits in those years. Economies of scale evaporate completely if one adjusts large banks’ operating costs by the implicit subsidy associated with their inflated credit ratings and too-big-to-fail status. This reality—that TBTF banks are prone to take excessive risks, while also enjoying protected status—continues largely unabated.

This is a continuity which is particularly evident in post-crisis studies of market sentiment. Consider the publication of the first G-SIB list by the Financial Stability Board in 2011 (FSB Citation2011). The banks so named were mandated to undertake restructuring and safety measures due to the threat they continued to pose to the global economy. If the idea was to stigmatize these institutions, this logic backfired. Replicating pre-crisis conditions, studies have found that this G-SIB (that is, TBTF) designation led investors to increase these banks’ market value (Moenninghoff, Ongena, and Wieandt Citation2015), and had a positive impact on the credit ratings of these banks’ debt instruments (Poghosyan, Werger, and de Haan Citation2016).

All this evidence validates Alessandri and Haldane’s notion of a self-perpetuating ‘doom loop’ involving megabanks (Citation2009). On top of the bailout costs that TBTF banks impose on taxpayers, too-big-to-fail policies lock in this loop: markets and rating agencies expect that large banks will have privileged access to public support; thus, these institutions’ funding costs fall and their leveraging rises; this permits them to grow even larger; further threatening the sustainability of public finances; and so on. What is more, explicit listings of TBTF (or ‘systematically important’) banks encourage entities close to the too-big-to-fail threshold to seek acquisitions to gain this status, since its benefits will more than offset the higher capital requirements and closer regulatory scrutiny it entails (Dymski Citation2011).

5. Post-Crisis Elements of a Circular Political Economy of Too-Big-To-Fail Banking

If this doom-loop scenario is as well-known as it is noxious, why does it persist? The answer is that its dynamics is supported by a persistent set of self-reinforcing political and market forces. These forces provide the material foundations for the reproduction of Alessandri and Haldane’s expectation-driven ‘doom loop.’ The elements of this circular political economy are as follows: consolidation policy favoring TBTF banks’ growth, quantitative easing policies protecting the value of their asset positions and their access to reserves, favorable regulatory treatment, bank lobbying validating TBTF-biased policies, and the global prominence of the US dollar. We explain these in turn.

5.1. Consolidation

There are two complementary paths to the creation of megabanks through consolidation. One, the deliberate strategic choice by national regulators to use consolidation to create or expand very large banks, discussed above, was in use well before the 2008 crisis. The second path emerges in the heat of severe financial crises. The critical actor in stabilizing financial markets is the central bank. Its lender-of-last-resort role—the provision of unlimited reserves to those cashing out of that bank’s currency—is needed to stop bank runs (on the role of central banks in financial crises see Dymski Citation2009). And if any of the ‘systematically important’ institutions within a central bank’s domain of action are in danger of insolvency, it must act fast to reassure markets that the holes they might leave will be plugged. This has to be done under time pressure; and central banks often ask private-sector intermediaries to come to the rescue. Those capable of rescue are invariably the remaining systematically important institutions. Thus, when crises hit, the circle of those institutions requiring rescue and those capable of providing it is very small indeed—a point dramatically made in the title of Johnson and Kwak’s book on the 2008 financial crisis: 13 Bankers. In sum, government policy choices and emergency interventions encompassing consolidation have combined to create and sustain the size and power of TBTF banks (also see Baily, Holmes and Bekker Citation2015; Reich Citation2018).

The 2007–2008 crisis provides many examples of using TBTF banks to address insolvency problems under time pressure. Two prominent examples associated with the sample of US banks studied here are the March 2008 purchase of Bear Stearns by JP Morgan, arranged by the Federal Reserve, and Bank of America’s July 2008 purchase of ailing mortgage lender Countrywide Financial, both in the early stages of the crisis. Once the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy occurred in September 2008, forced large acquisitions came thick and fast: among others, Washington Mutual was sold to JP Morgan, Bank of America purchased Merrill Lynch, and Wachovia was purchased by Wells Fargo. Transactions this large required several waivers of the rule prohibiting any bank from holding more than 10 per cent of national retail deposits (Johnson and Kwak Citation2010). The solvency of these acquiring megabanks was itself in question. This was addressed by the Capital Purchase Program (CPP), part of the emergency legislation passed on 3 October 2008. Between 28 October 2008 and December 2009, the US Treasury provided some $205 billion in capital injections; of this, $120 billion went to the ‘big six’ US banks, and an average of $13.9 billion to each of the 10 largest banks; 723 other banks received injections (median amount, $10.9 million).Footnote6 As demonstrates, of the six largest US banks, the three that grew (JP Morgan, Bank of America and Wells Fargo) did so through crisis-related 2008 acquisitions.

Acquisitions also affected the fortunes of several of the non-US banks in our sample. BNP grew largely because of its acquisition of troubled Fortis Bank Belgium in 2008 and of Fortis Bank Luxembourg in 2009. The merger of Banques Populaires with the Caisses d’Epargne also allowed BPCE to become the second biggest French bank, recording a 40 per cent increase in its combined asset size between 2007 and 2017 (). In turn, Mitsubishi grew because of a strategic alliance it forged with Morgan Stanley in September 2008 (which made Mitsubishi into Morgan Stanley’s largest shareholder).

In the UK, the government provided capital injections: £37 billion for RBS and Lloyds Bank, with a portion of the Lloyds’ injection provided for its taking over the failing HBOS (Marshall Citation2013). Under this recapitalization, the Treasury acquired stakes in these two banks of over 70 per cent and 40 per cent, respectively, in these two institutions.Footnote7 Two troubled former building societies, Abbey National and Bradford and Bingley were sold to TBTF Spanish bank Santander.

Note that the operative goal for both the US and UK authorities in injecting large amounts of capital into their banking sectors was economic and financial stabilization, not nationalization. The UK government sold off its final shares in Lloyds in 2017. In June 2018 it also reduced its ownership position in the RBS by selling 925 million shares (about 7.7 per cent of bank’s stock) at a price close to half of what was paid in 2008 to acquire its 70 per cent stake, resulting at a loss of more than £2bn for the public.Footnote8 In the US, all but a handful of the 707 institutions receiving CPP-program capital injections have paid them off (US Government Accountability Office Citation2015).

5.2. Quantitative Easing

The second element sustaining the size and influence of TBTF megabanks in the post crisis period has been quantitative easing (QE). QE constitutes an unconventional form of monetary policy. Under conventional monetary policy, a central bank intent on stimulating the economy buys or sells short-term government assets so as to maintain a target interbank interest rate; lowering that target rate should stimulate investment and speed economic growth and increasing it should slow the economy. Under QE, a central bank buys either government bonds or private-sector assets (or both) on a large-scale basis, primarily from banks. Doing so increases the amount of reserves in the economy. The intent of QE is the same as that of stimulative conventional monetary policy—to increase the market price of financial assets, drive down interest rates, and spur borrowing and economic growth. In Japan, it has been used since the early 2000s to fight deflation. QE has been used by the US since November 2008; it started with large-scale purchases of mortgage-backed securities, the market for which had collapsed. The Bank of England followed suit as of March 2009; the European Central Bank embarked on large-scale QE only in 2015.

Insofar as QE is an extreme version of traditional monetary policy, some analysts have argued that the excess reserves it creates will eventually increase lending and stimulate economic activity.Footnote9 But lending by banks, including megabanks, has grown more slowly—not accelerated—in the post-crisis period (see for instance in Seccareccia Citation2017 for a depiction of lending and reserves in the US).

On the other hand, QE permitted banks—especially TBTF banks—to remove precarious securities from their balance sheets, while sustaining the demand for risky securitized assets after the market for these assets had collapsed. To this extent, QE effectively sustained the shadow-banking system that ‘systematically important’ financial institutions had created. The excess reserves released by QE have been needed to support the massive volume of securitized loans and contingent contractual commitments in the shadow-banking system, after market liquidity—and hence shadow-banking-supported credit flows—dried up after the crisis (Pollin Citation2012). QE thus ‘reinforced the statistical decoupling between base money and the money supply and between deposits and loans’ (Caldentey Citation2017).

5.3. Regulation

Given that post-crisis consolidation and QE policies have been used to preserve, not dismantle, the TBTF-dominated banking system, it is not surprising that the downsizing and radical regulatory reform proposed by Johnson and Kwak (Citation2010), among others, has not been seriously considered. Furthermore, as elaborated in Bell and Hindmoor (Citation2018), regulation in the US and Europe has done very little in re-structuring the markets in which banks operate, as for instance the shadow banking system.

Taking no action towards the re-regulation of finance could never have been an option, given the public outrage against banks that followed the crisis. As discussed earlier, one step has been the intention to ring-fence large banks by internally separating their retail and investment branches (see ICB Citation2011; Liikanen et al. Citation2012). In the case of the UK, ring-fencing is to come into force in 2019. In that of the EU, the key parts of the Liikanen proposal were embodied in a regulatory proposal of the European Commission, published in early 2014 (EC Citation2014). The proposal was nevertheless met with pre-emptive legislation by key member states, most notably France and Germany, which sought to protect their own megabanks by establishing their own, much lighter, versions of ring-fencing (Hardie and Macartney Citation2016). At the European level, Commission’s proposal was officially abandoned in 2017 (EC Citation2017).

The second aspect of new regulation has been the recommendation of additional capital buffers. FSB’s listing of global TBTF banks for example, and their ranking by systemic importance primarily aims at exactly that. Third, the idea of resolution schemes for insuring an orderly winding down of failing institutions, with losses attributed to bank owners and unsecured creditors rather than the public, has gained support (consider for instance the Dodd-Frank Act and the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive, in the US and the EU respectively). As mentioned by Quaglia and Spendzharova (Citation2017) in the context of the EU though, resolution schemes are still largely untested in practice, rigged with practical difficulties and complexities, e.g. with respect to who takes priority in bailing-in a failing institution.

In some cases—for example, in Switzerland—capital requirements have exceeded the guidelines put forward by FSB and Basel. It is important to note however that while global guidelines apply to all globally active banks, they have the status of recommendations, not regulatory mandates. Financial intermediaries, no matter how globalized their activities, are still creatures of national law (Pistor Citation2013).

These global and national regulatory mandates spurred megabanks into action. They have found additional capital through any means available,Footnote10 have employed thousands of additional compliance staff, and have developed regtech to automate their compliance functions.

5.4. Bank Lobbying

The next link in the circular political economy of too-big-to-fail banking is bank lobbying. Wall Street’s historical role in lobbying for financial deregulation is long-established and well documented (see Dymski Citation2011). The political influence of the banking lobby in the US is rooted in their financial contributions to political parties and election campaigns, and to the ‘revolving door’ between big banks and the public sector, including Congress, financial regulatory agencies, and the Federal Reserve (Dymski Citation2011; Harris Citation2013). Investment bankers have regularly played central policy roles in US national governments. Three out of four US Secretaries of the Treasury since 2006 had careers in investment banking prior to their appointment, including Henry Paulson (2006–2009) and Steven Mnuchin (2017–), both from Goldman Sachs.

Wall Street’s reaction to the Dodd-Frank Act is perhaps the best example for displaying the contemporary influence of lobbying in the US. From day one megabanks did their best to strip the Act from its relatively most radical components. Volcker Rule’s prohibition of proprietary trading for example ended up with numerous loopholes (e.g. exception of foreign exchange trading; see Oran Citation2016). Similarly, the consideration of a cap on bank size soon turned into an ordinary liquidation process which ultimately took the shape of a ‘bailout now, pay later’ mechanism wherein megabanks are still to be bailed out using taxpayers’ money with the prospect of recovering that money from banks later on (Taibbi Citation2012). After the final version of the Act was signed, Wall Street banks continued to sue regulators, effectively removing parts of the bill one at a time (e.g. position limits in derivatives market), while they also managed to postpone implementation of the surviving part of the bill for almost five years (Taibbi Citation2012; Oran Citation2016). Often over seemingly technical issues, and while public sentiment was cooling down, bank lobbyists kept on fighting the bill day in and day out (Taibbi Citation2012).

Banking lobbyists also have a huge degree of influence in Europe. They have played a central role in the formation of both the European Banking and Capital Markets Unions. The former is harmonizing bank regulation, regulation and deposit insurance throughout the European Union, while the latter is establishing uniform guidelines for securitization. These initiatives provide major opportunities for megabanks to expand their operations within and across national borders.Footnote11 Ongoing efforts to create these Union frameworks also focuses attention on the lack of regulatory harmonization and coordination as the primary source of European banking problems and prepares the way for European megabanks to argue that too-big-to-fail concerns will diminish once EU and not national GDP is used to determine whether their large banks’ size demands policy action. On what has to do with revolving doors in Europe, it suffices to note that the two most powerful central bank governors, Mark Carney of the Bank of England and Mario Draghi of the European Central Bank, are both former employees of Goldman Sachs.

Also note that in the post-crisis era, not only do banks spend more money on lobbying, they do so in a more coordinated manner. This is illustrated by the formation of the Global Financial Markets Association, which provides ‘a forum for global systemically important banks to develop policies and strategies on issues of global concern within regulatory environment’ (GFMA Citation2013). The organization, headquartered in New York, brings together three of the world’s leading financial trade associations: London- and Brussels-based Association for Financial Markets in Europe, Asia Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association in Hong Kong, and New York-based Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. The GFMA provides an example of how bank lobbying has become globalized in response to the new wave of international coordination in financial regulation, notably the FSB.

5.5. The US Dollar and the Geo-Politics of Megabanking

The final component in the interlocking political economy of too-big-to-fail banking consists of several critical elements of the international monetary architecture. While this topic deserves more detailed treatment, four general points are brought into focus here. The first is the fact—and the consequences—of the persistent US current-account deficit throughout the entire period from 1982 to the present. This deficit has been accompanied by a persistent financial-account surplus. These two accounts must balance, net of the change in dollars held abroad as reserves. The key consequence of this sustained imbalance is that the continuing inflow of foreign wealth has provided a steady stream of demand for dollar-denominated assets. This is the structural root of the explosion in securitization which began when the ‘triple crisis’ of the early 1980s decimated the US’s local savings-and-loan-based mortgage finance system. The stream of mortgage-backed securities bundled and sold by the megabank complex—first ‘plain vanilla’ paper, later mixed with subprime and alt-A mortgages and other loan types—were soaked up in part by a steady inflow of foreign savings, which has continued to the present day. This, in turn, gave US megabanks, and the shadow-banking system that grew up around it in the 1990s, a big head-start as they led the way from bank-based to market-based finance—a transition that European financial systems are still negotiating.Footnote12

The second point involves the undisputed primacy of the US dollar as a global reserve and transaction currency. As noted in Cohen (Citation2011), a successful international currency requires a broad transactional network, with a large number of sellers and buyers. US megabanks, with direct access to the Federal Reserve Bank and a global network of subsidiaries, branches and global operations, are key intermediaries in the global dollar network. If anything, their role has grown over time. The world has witnessed major institutional concentration in foreign exchange trading: whereas in 1998 it took 20 banks to account for 75 per cent of all foreign exchange trading in the US, in 2010 it took only 7 (BIS Citation2010).

The third geo-economic factor stems from the unparalleled crisis-capacity of the US Federal Reserve. Start with the factors just mentioned—the steady inflows of foreign capital into the US since 1982 and the dollar’s favored position as a global reserve and transaction currency. Then consider that the global reach of Wall Street has steadily grown since World War I; and note that while US megabanks are among the world’s largest financial institutions, their size as a share of national GDP is much lower than for any other megabank’s home country due to the US economy’s immense scale. Given this combination of factors, the Federal Reserve is able to intervene more aggressively and effectively than any other nation’s central bank. This can help explain why the US has been at the forefront of financial deregulation during the years since 1980. That is, in any financial crisis involving cross-border lending and borrowing, the Federal Reserve has far more capacity as a lender-of-last-resort role than can any other central bank; indeed, it is effectively the international lender of last resort. This has been true for decades; and through these years, US financial regulators have had less incentive than other central banks to maintain their banks on a safe-and-sound basis. Financial crises across the globe have only reinforced the safe-haven status of the US. US-based megabanks are not only too-big-to-fail; they embody the impervious structural position of the US in the global economy.

The fourth and final factor involves the failure of global regulatory co-ordination and the desire to protect national banking champions. Notice that the preservation of banking champions is closely connected with the positioning of countries as hosts of international financial centers, a positioning that is by its nature hierarchical and deeply political (Cassis Citation2006). US megabanks not only reflect and enhance the power of the US dollar as the international currency of choice, but also the status of New York as the world’s biggest financial center. For both these reasons, breaking them down poses a political quandary. As law professor Hal Scott put it: ‘If we break up our banks and Europe does not break up theirs and the Chinese don’t break up theirs, this is going to have an immense impact on who are the players in the international banking system’ (quoted in Johnson and Kwak Citation2010, p. 217).

A similar rationale can also be found on the other side of the Atlantic, particularly in France and Germany. As for instance stated by Christian Noyer, governor of the Bank of France until 2015, was France to ring-fence its banks, it ‘would have only found Wall Street banks to place its debt. Companies would have only found Wall Street banks to finance their operations’ (quote in Hardie and Macartney Citation2016, p. 517). Goldstein and Véron (Citation2011) write that the logic of the national banking champions has a particularly long history in the case of Europe, due to the continent’s composition of centralized nations with strong cross-border financial linkages with each other. They point out that Deutsche Bank, for example, was created in 1870 in Berlin in part to offset the international dominance of British banks in the context of the formation of the German Empire.

The growing size of Chinese banks, elaborated in and , adds further strength to these geopolitical concerns. As of the end of 2017, the world’s four largest banks by total assets were Chinese (Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, China Construction Bank, Agricultural Bank of China, Bank of China, in that order); these banks commanded assets of over US$13.6 trillion, a total representing over 100 per cent of China’s GDP (see and ). For comparison, the top four US banking groups (JP Morgan, Bank of America, Citigroup and Wells Fargo) held US$8.6 trillion. While the rise of RMB and China’s growing geopolitical position might weaken the hegemony of the US dollar, it will not solve the too-big-to-fail problem. As Chinese banks expand internationally, partly in the service of RMB internationalization and of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, they become too-big-to-fail themselves. Further, their size and growing global presence is likely to discourage, if not prevent, any radical responses to too-big-to-fail problems elsewhere in the world.

6. Conclusion and a Policy Proposal

This investigation of the post-crisis landscape of too-big-to-fail (TBTF) banking has examined 31 banks listed as global-systemically important by the Financial Stability Board. We have attempted to frame an answer to the question of why this global megabanking sector—a sector comprised of institutions whose very scale, complexity, interconnectedness, and risk-tolerance have already proven to be a toxic mix—is still so large and powerful ten years after the global financial crisis. Our answer involves the interaction between two sets of factors.

One root cause of this persistence lies in prevailing economic models of banking, which are rooted in the idea of financial-market efficiency. In this view, banks’ default role is one that promotes the overall-efficiency in economic transactions. Due to their size, large banks are then claimed to be best equipped for performing such task. In this setting, financial instability can at best arise out of moral hazard issues. Moreover, market forces are conceived as part of the solution thanks to their supposed disciplinary nature. From this stance, the objective of financial regulation is not to ‘over-regulate’ the sector, but to establish the necessary rules for allowing those forces to play out in a sober way. Both pre- and post-crisis, this view of banking has exercised a very persistent influence on regulators and policy makers, and hence there are material effects emanating from it.

The second reason for the failure of TBTF banks to shrink is their embedding in a material political economy comprised of five self-reinforcing elements. Consolidation supported by regulatory authorities has bolstered those banks’ size in the midst of crisis. The monetary policy of quantitative easing has also helped to maintain the size of megabanks by providing balance-sheet support and shoring up their liquidity—little of which was used by these banks to provide credit to other units in the economy. National and international financial regulation did not address the issue of bank size directly, relying instead on stricter capital requirements, and closer monitoring of megabanks. This was supported by an extensive bank lobbying effort, domestically and globally. Geo-political considerations reinforce this approach, as national authorities in the US and Europe see their banking ‘champions’ as an extension of their international power, particularly in the context of the rising power of China’s fast-growing megabanks.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the principal policy recommendation stemming from this analysis is the need to break up TBTF banks. In principle this could either be done by setting a cap on their size, such as 100 per cent of home-nation GDP, by completely separating retail from investment banking, as per the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act, or by a combination of the two. The trouble in the first case is the arbitrariness that governs the calculation of any threshold: e.g. why not 90 per cent of GDP, or 110 per cent? In addition, it is easy to imagine large banks seeking increases in any such GDP-size threshold once financial stability has apparently been permanently restored—a state of affairs that Minsky (Citation1992, 7–8) identifies as a precondition for further financial instability. A further complication is that country-size hardly provides a neutral competitive standard. Even the largest US megabanks, in particular, represent a a small percentage of national GDP due to the vast size of the US economy, in contrast to the situation of nationally-chartered European banks.

Separating investment from commercial banking arguably rests on a more robust logic, as public protection could potentially be offered to commercial banks in exchange for their provision of those portions of banking activity—such as deposit-taking and the provision of credit to small and medium enterprises—that undergird everyday economic activity, and for their forgoing excessively risky activities, such as trading in opaque financial instruments. Critics of this idea, such as Elliott (Citation2015), have correctly pointed out that traditional banking is not necessarily safer. That said, this reform would at least create the potential for improved transparency in core banking operations and thus for both more effective regulation and more timely intervention. Moreover, in comparison with the internal ring-fencing put forward in the Liikanen and Vickers reports, the complete separation is a more robust reform, and therefore has a higher likelihood of survival in the medium-run once the lessons of the global financial crisis start evaporating.

One problem that complete separation does not address, except at the moment of its implementation is the possibility that commercial banks become too-big-to-fail again. After all, the Glass-Steagall Act was still in place when too-big-to-fail first emerged as a policy concern in the US. In this respect, a combination of separation and a size cap could represent a better approach, even if the latter would be relatively arbitrary and in need of adjustment by country. Ideally, any such reform should be taken as part and parcel of the broader transformation of the pre-crisis model of banking.

Given the exploratory nature of this investigation, further research on the mechanisms identified here as sustaining too-big-to-fail banking will yield deeper understanding and more targeted policy proposals. In particular, future research could investigate interactions among the political economy elements examined here—a complex task requiring interdisciplinary effort. Beyond this, the broader economic risks posed by the continuing existence of too-big-to-fail banking deserves further exploration. Macroeconomic theories that take seriously the endogenous processes of financial instability, including those based on the insights of Keynes and Minsky, could be enriched by incorporating a deeper engagement with the meso-level analysis of too-big-to-fail banking initiated in this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the participants of the Grenoble Post-Keynesian and Institutionalist Conference ‘Instability, Growth & Regulation’ (Grenoble, December 2017) and those of the 22nd Conference of the Research Network of Macroeconomics and Macroeconomic Policies (FMM) ‘10 Years After the Crash: What Have We Learned?’ (Berlin, October 2018) for their fruitful comments and feedback. They are also grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their useful remarks on an earlier draft of the paper. This work has been supported by the European Research Council (European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program) under grant agreement No. 681337. The article reflects only the authors’ views and the European Research Council is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Since its founding in 1986, the Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee, as well as its individual members, have been the most persistent critics of too-big-to-fail protection from a similar prism; see Kaufman (Citation1990) and Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee (Citation2010) for notably similar analyses separated by 20 years.

2 These authors’ list is based on the criteria identified by DeFerrari and Palmer (Citation2001).

3 Hereafter we use the terms TBTF and G-SIB interchangeably.

4 The 31 banks of the sample include the 4 biggest Chinese banks. These banks are listed as G-SIB by the FSB mainly due to their size rather than their interconnectedness with the rest of the global megabanks. While the discussion that follows is not comprehensive enough to penetrate the dynamics of Chinese banking (something that lies outside scope of the paper), the exponential rise in the size of Chinese banks is of relevance in understanding the persistence of too-big-to-fail banking in the US and Europe (see discussion in section 5.5). This is why we choose to incorporate them into our sample.

5 Since 2014, there is a two-year distance between the date of the announcement of the FSB list and the date by which listed banks are expected to meet the updated capital requirements.

6 ‘The rescue: bailed out banks,’ CNN Money special report, undated.

7 RBS was in FSB’s list for all the years up until 2017. Lloyd’s was included in the 2011, but was subsequently removed.

8 Partington R. 2018. ‘UK Government to Sell 7.7% Stake in RBS Worth Almost £2.6bn’. The Guardian, June 4.

9 See for example, Barro 2010. ‘Thoughts on QE2’, The Economist, November 23.

10 In the case of Barclays, this has involved dubious means; see Binham 2017. ‘Barclays and Former Executives Charged with Crisis-Era Fraud’. Financial Times, June 20.

11 See Corporate Europe Observatory 2014. ‘A Union for Big Banks’, Corporate Europe Observatory, January 24.

12 This point and the third point made below are based on Dymski (Citation2011, Citation2017).

References

- Alessandri, P., and A. Haldane. 2009. ‘Banking on the State.’ Paper presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago 12th annual international banking conference on “The International Financial Crisis: Have the Rules of Finance Changed?”, Chicago, September, 25.

- Baily, M. N., S. E. Holmes, and W. Bekker. 2015. ‘The Big Four Banks: The Evolution of the Financial Sector, Part I.’ Economic Studies at Brookings Institution (May).

- Bank for International Settlements. 2010. ‘Triennial Central Bank Survey: Report on Global Foreign Exchange Market Activity In 2010.’ Bank for International Settlements, Basel. Accessed July 22, 2019. https://www.bis.org/publ/rpfxf10t.pdf.

- Bank for International Settlements. 2013. ‘Global Systemically Important Banks: Updated Assessment Methodology and the Higher Loss Absorbency Requirement.’ Bank for International Settlements. Accessed July 22, 2019. https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs255.pdf.

- Beccalli, E., M. Anolli, and G. Borello. 2015. ‘Are European Banks Too Big? Evidence on Economies of Scale.’ Journal of Banking and Finance 58: 232–246.

- Bell, S., and A. Hindmoor. 2018. ‘Are the Major Global Banks Now Safer? Structural Continuities and Change in Banking and Finance Since the 2008 Crisis.’ Review of International Political Economy 25 (1): 1–27.

- Brewer, E., and J. Jagtiani. 2013. ‘How Much Did Banks Pay to Become Too-Big-To-Fail and to Become Systemically Important?’ Journal of Financial Services Research 43 (1): 1–35.

- Caldentey, E. P. 2017. ‘Quantitative Easing (QE), Changes in Global Liquidity, and Financial Instability.’ International Journal of Political Economy 46 (2–3): 91–112.

- Carow, K. A., E. J. Kane, and R. P. Narayanan. 2011. ‘Safety-Net Losses from Abandoning Glass-Steagall Restrictions.’ Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 43 (7): 1371–1398.

- Cassis, Y. 2006. Capitals of Capital: A History of International Financial Centres, 1780–2005. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cassis, Y., and D. Wójcik. 2018. International Financial Centres after the Global Financial Crisis and Brexit. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cecchetti, S. G., and E. Kharroubi. 2012. ‘Reassessing the Impact of Finance on Growth.’ BIS Working Papers No. 381. Basel: Bank for International Settlements. Accessed July 22, 2019. https://www.bis.org/publ/work381.pdf.

- Cohen, B. J. 2011. The Future of Global Currency: The Euro Versus the Dollar. Abington: Routledge.

- Davies, R., P. Richardson, V. Katinaite, and M. Manning. 2010. ‘Evolution of the UK Banking System.’ Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin Q 4: 321–332.

- DeFerrari, L. M., and D. A. Palmer. 2001. ‘Supervision of Large Complex Banking Organizations.’ Federal Reserve Bulletin 87 (5): 47–57.

- De la Mano, M. 2015. ‘Bank Structural Reform and Too-Big-To-Fail.’ In Too Big to Fail III: Structural Reform Proposals: Should We Break Up the Banks?, edited by A. Dombret, and P. Kenadjian. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- De Young, R., D. Evanoff, and P. Molyneux. 2009. ‘Mergers and Acquisitions of Financial Institutions: A Review of the Post-2000 Literature.’ Journal of Financial Services Research 36 (2): 87–110.

- Diamond, D. 1984. ‘Financial Intermediation and Delegated Monitoring.’ Review of Economic Studies 51 (3): 393–414.

- Diamond, D., and P. Dybvig. 1983. ‘Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity.’ Journal of Political Economy 91 (3): 401–419.

- Dymski, G. 1999. The Bank Merger Wave: The Economic Causes and Social Consequences of Financial Consolidation. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

- Dymski, G. 2002. ‘The Global Bank Merger Wave: Implications for Developing Countries.’ The Developing Economies 40 (4): 435–466.

- Dymski, G. 2009. ‘Financial Risk and Governance in the Neoliberal Era.’ In Managing Financial Risks: From Global to Local, edited by G. L. Clark, D. A. Dixon, and A. Monk. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dymski, G. 2011. ‘Genie Out of the Bottle: The Evolution of Too-Big-To-Fail Policy and Banking Strategy in the US.’ Post-Keynesian Study Group Working Paper. Accessed July 22, 2019. https://www.postkeynesian.net/downloads/soas12/Dymski-Banking-and-TBTF.pdf.

- Dymski, G. 2017. ‘Does Sustainable Global Prosperity Require Global Financial Governance?’ In Financialisation and the Economy, edited by K. Opolski, and A. Gemzik-Salwach. London: Routledge.

- Elliott, D. 2015. ‘Ten Arguments Against Breaking Up the Big Banks.’ In Too Big to Fail III: Structural Reform Proposals: Should We Break Up the Banks?, edited by A. Dombret, and P. Kenadjian. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- European Commission. 2014. ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of The Council on Structural Measures Improving the Resilience of EU Credit Institutions.’ January 29, 2014/0020. Accessed July 22, 2019. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014PC0043&from=EN.

- European Commission. 2017. ‘2018 Commission Work Programme. An Agenda for a More United, Stronger and More Democratic Europe – Annex IV: Withdrawals.’ October 24. Accessed July 22, 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/cwp_2018_annex_iv_en.pdf.

- Fama, E. 1980. ‘Banking in the Theory of Finance.’ Journal of Monetary Economics 6 (1): 39–57.

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. 1997. History of the Eighties – Lessons for the Future. Volume 1: An Examination of the Banking Crises of the 1980s and Early 1990s. Washington, DC: FDIC.

- Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. 2011. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Financial Stability Board. 2011. ‘Policy Measures to Address Systemically Important Financial Institutions.’ Financial Stability Board. November 4. Accessed July 22, 2019. http://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/Policy-Measures-to-Address-Systemically-Important-Financial-Institutions.pdf.

- Financial Stability Board. 2013. ‘Progress and Next Steps Towards Ending “Too-Big-To-Fail” (TBTF). Report of the Financial Stability Board to the G-20.’ September 2. Accessed July 22, 2019. http://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/r_130902.pdf?page_moved=1.

- Financial Stability Board. 2017. ‘2017 List of Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs).’ Financial Stability Board. November 21. Accessed July 22, 2019. http://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P211117-1.pdf.

- Financial Stability Board. 2018. ‘2018 List of Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs).’ Financial Stability Board. November 16. Accessed July 22, 2019. http://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P161118-1.pdf.

- Frankopan, P. 2015. The Silk Roads: A New History of the World. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Global Financial Markets Association. 2013. ‘GFMA Membership Brochure.’ Accessed July 22, 2019. http://asifma.org/uploadedFiles/About/GFMA-Membership-Brochure.pdf.

- Goldstein, M., and N. Véron. 2011. ‘Too Big to Fail: The Transatlantic Debate.’ Bruegel Working Paper. 2011/03. Accessed July 22, 2019. http://bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/publications/Nicolas_Veron_WP_Too_big_to_fail_2011_03.pdf.

- Haldane, A. 2012. ‘On Being the Right Size.’ Speech given at the Institute of Economic Affairs’ 22nd Annual Series, The 2012 Beesley Lectures, London, October, 25.

- Hardie, I., and H. Macartney. 2016. ‘EU Ring-Fencing and the Defence of Too-Big-To-Fail Banks.’ West European Politics 39 (3): 503–525.

- Harris, S. 2013. ‘Does “Too Big To Fail” Signal the Triumph of Business Power?’ The Forum 11 (1): 17–32.

- Hughes, J., and L. Mester. 2013. ‘Who Said Large Banks Don’t Experience Scale Economies? Evidence from a Risk-Return-Driven Cost Function.’ Journal of Financial Intermediation 22 (4): 559–585.

- Independent Commission on Banking. 2011. ‘Final Report Recommendations.’ Independent Commission on Banking. September 12. London: Domarn Group.

- Ingham, G. 2013. The Nature of Money. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Johnson, S., and J. Kwak. 2010. 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Kaufman, G. 1990. ‘Are Some Banks Too Large to Fail? Myth and Reality.’ Contemporary Economic Policy 8 (4): 1–14.

- Kozubovska, M. 2017. ‘Breaking Up Big Banks.’ Research in International Business and Finance 41: 198–219.

- Liikanen, E., H. Bazinger, J. M. Campa, L. Gallois, M. Goyens, J. P. Krahnen, M. Mazzucchelli, et al. 2012. ‘High-Level Expert Group on Reforming the Structure on the EU Banking Sector.’ European Commission Report. October 2. Brussels.

- Marshall, J. 2013. ‘A Geographical Political Economy of Banking Crises: A Peripheral Region Perspective on Organisational Concentration and Spatial Centralisation in Britain.’ Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 6 (3): 455–477.

- Maycock, J. 1986. Financial Conglomerates: The New Phenomenon. London: Gower Publishing.

- Minsky, H. 1992. ‘The Financial Instability Hypothesis.’ Working Paper no. 74, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: The Jerome Levy Economics Institute, May.

- Mishkin, F. 1999. ‘Financial Consolidation: Dangers and Opportunities.’ Journal of Banking & Finance 23: 675–691.

- Mishkin, F. 2007. The Economics of Money, Banking and Financial Markets. New York: Pearson.

- Moenninghoff, S., S. Ongena, and A. Wieandt. 2015. ‘The Perennial Challenge to Counter Too-Big-To-Fail in Banking: Empirical Evidence from the New International Regulation Dealing with Global Systemically Important Banks.’ Journal of Banking and Finance 61: 221–236.

- Moosa, I. 2010. ‘The Myth of Too Big to Fail.’ Journal of Banking Regulation 11 (4): 319–333.

- O’ Hara, M., and W. Shaw. 1990. ‘Deposit Insurance and Wealth Effects: The Value of Being “Too Big to Fail”.’ Journal of Finance 45 (5): 1587–1600.

- Oran, O. 2016. ‘Exclusive: Wall St. Banks ask Fed for Five More Years to Comply with Volcker Rule.’ Reuters, August 11. Accessed July 22, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-fed-volcker-exclusive-idUSKCN10M2E4.

- Pistor, K. 2013. ‘A Legal Theory of Finance.’ Journal of Comparative Economics 41 (2): 315–330.

- Poghosyan, T., C. Werger, and J. de Haan. 2016. ‘Size and Support Ratings of US Banks.’ North American Journal of Economics and Finance 37: 236–247.

- Pollin, R. 2012. ‘The Great US Liquidity Trap of 2009–2011: Are We Stuck Pushing on Strings?’ Review of Keynesian Economics 1: 55–76.

- Quaglia, L., and A. Spendzharova. 2017. ‘The Conundrum of Solving ‘Too Big to Fail’ in the European Union: Supranationalization at Different Speeds.’ Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (5): 1110–1126.

- Reich, R. 2018. ‘Why the Only Answer is to Break Up the Biggest Wall Street Banks.’ Author’s Personal Website. June 7. Accessed July 22, 2019. https://robertreich.org/post/174478321450.

- Schoenmaker, D. 2017. ‘What Happened to Global Banking after the Crisis?’ Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 25 (3): 241–252.

- Seccareccia, M. 2017. ‘Which Vested Interests Do Central Banks Really Serve? Understanding Central Bank Policy Since the Global Financial Crisis.’ Journal of Economic Issues 51 (2): 341–350.

- Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee. 2010. ‘Resolution and Bailout of Large Complex Financial Institutions.’ Shadow Statement No. 292. April 26. Accessed July 22, 2019. http://www.aei.org/publication/resolution-and-bailout-of-large-complex-financial-institutions/.

- Stern, G. H., and R. J. Feldman. 2004. Too Big to Fail: The Hazards of Bank Bailouts. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Stolz, S. M., and M. Wedow. 2010. ‘Extraordinary Measures in Extraordinary Times – Public Measures in Support of the Financial Sector in the EU and The United States.’ Discussion Paper Series 1: Economic Studies No 13/2010. Frankfurt-em-Main: Deutche Bundesbank. Accessed July 22, 2019. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/37071/1/631858768.pdf.

- Taibbi, M. 2012. ‘How Wall Street Killed Financial Reform.’ Rolling Stone. May 10. Accessed July 22, 2019. https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/how-wall-street-killed-financial-reform-190802/.

- Tooze, A. 2018. Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World. London: Allen Lane.

- Turner, A. 2010. ‘What Do Banks Do? Why Do Credit Booms and Busts Occur and What Can Public Policy Do About It?’ In The Future of Finance and the Theory that Underpins It: The LSE Report, edited by A. Turner and others. London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

- US Government Accountability Office. 2015. ‘Troubled Asset Relief Program: Status of Remaining Investment Programs.’ Report GAO-16-91R. November 15. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Walby, S. 2009. Globalization and Inequalities: Complexity and Contested Modernities. London: Sage Publications.

- Wójcik, D., E. Knight, P. O’Neill, and V. Pažitka. 2018. ‘Economic Geography of Investment Banking Since 2008: The Geography of Shrinkage and Shift.’ Economic Geography 94 (4): 376–399.

- Zysman, J. 2003. Governments, Markets, and Growth: Financial Systems and the Politics of Industrial Change. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.