?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article views analysis of the influence of capital–labour income distribution on economic growth from a historical perspective, using data from 1900 onwards. We study the three Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Denmark and Norway, where conventional accounts of the postwar growth miracles in these small, open economies have emphasized the role of wage restraint, favouring profits and investment over consumption. Instead, we show that the 1950s and 1960s saw growing wage shares, and use the Bhaduri–Marglin model to econometrically analyse the effects on consumption, investment, exports and imports and the total effects on GDP. Furthermore, we estimate the effects of wage pressure on labour productivity. Growing wage shares have had a small positive effect on GDP growth in Sweden, Denmark and Norway, and the positive effect was larger in the postwar period than in other times. However, the positive growth effects of wage pressure were modest as the demand was only weakly wage-led. In contrast, supply side effects were large. Labour productivity was stimulated by vigorous wage increases, as argued by the Swedish Rehn–Meidner model as well as by post-Keynesian economists. The present investigation opens several further avenues for research on the distribution–growth nexus.

1. Introduction

This paper investigates the effect of changes in the distribution of income between labour and capital on economic performance. Recent decades have seen a proliferation of such studies in a broadly (post-)Keynesian tradition, emanating from Bhaduri and Marglin’s (Citation1990) seminal contribution. Here, it is recognized that a wage push, increasing labour’s share of the pie, can have a negative effect on investment and exports while increasing consumption. Thus, depending on the respective size of the effects, the demand regime may be wage-led or profit-led overall. Numerous empirical studies have identified demand regimes (e.g. Hein and Vogel Citation2008; Hein and Tarassow Citation2010; Naastepad and Storm Citation2006; Stockhammer, Onaran, and Ederer Citation2009); however, with one recent exception only, they have covered the post-1970 period. This paper joins that of Stockhammer, Rabinovich, and Reddy (Citation2018) in a new venture to apply the Bhaduri–Marglin model to historical data.

While Stockhammer, Rabinovich, and Reddy (Citation2018) analyse four large economies, Britain, France, Germany and the United States, this paper studies the three Scandinavian countries, Sweden, Denmark and Norway. These countries are very relevant to the debate for two reasons. First, in the mainstream economic history literature on postwar growth, these ‘coordinated market economies’ with centralized wage bargaining have been pointed to as exemplars of voluntary wage restraint policies, where this restraint on behalf of workers increased investment and thereby growth (e.g. Katzenstein Citation1985; Moene and Wallerstein Citation1995; Vartiainen Citation1998; Eichengreen and Iversen Citation1999; Alexopoulos and Cohen Citation2003; Eichengreen Citation2007, pp. 32–41, 263–268). Second, the Scandinavian countries, with their strong trade unions and expansive welfare states in the postwar period, in fact saw the development of economic policy analyses that were quite different to the wage restraint paradigm – especially the famed Swedish Rehn–Meidner model of wage policy and economic policy (Ekdahl Citation2001; Erixon Citation2008, Citation2011, Citation2018). According to the trade union economists Rehn and Meidner, wage pressure would induce structural transformation and stimulate productivity growth; we provide a quantitative investigation of this argument. Analysing a longer time frame than the widely analysed post-1980 period, our study covers periods of growing wage shares (the 1950s to the 1970s) as well as periods of decreasing shares (since the 1980s). Still, as Storm and Naastepad (Citation2012, p. 197) have stated, ‘there is not much econometric evidence on the wage-led or profit-led nature of Nordic macroeconomic growth in the existing empirical literature’.

The contribution of this paper, then, is twofold. First, vis-à-vis debates in economic history, it broadens and deepens our understanding of the distribution–growth nexus; economic historians have so far failed to explicitly consider different demand regimes. Second, it gives a historical perspective to the post-Keynesian debate on the connection between distribution and growth; almost all of the existing literature on the Bhaduri–Marglin model analyses the postwar era only.

The paper is structured as follows. Section Two introduces the analytical framework, which starts with Bhaduri and Marglin’s (Citation1990) seminal contribution. Section Three discusses the context of the investigation: Scandinavia during the 20th century. Section Four discusses data and methodology. The empirical results are presented in Section Five, and Section Six concludes.

2. Wages, factor shares and economic growth: An analytical framework

The wage share is the share of national income that accrues to labour, as wages and other forms of compensation. With the capital share — the share that is paid as profits, rents, dividends and other forms of capital income — it adds up to 100 per cent. It is widely recognized in various theoretical traditions that income distribution has consequences for economic performance and growth, and this paper is concerned with the effects on economic growth that result from changes in the wage share.

Bhaduri and Marglin (Citation1990) clarified that, depending on the different sensitivities of consumption, investment and exports to the wage bill and the profit sum, the demand regimes of a capitalist economy can be either wage-led or profit-led. Following Bhaduri-Marglin and later studies in this tradition (see Lavoie and Stockhammer Citation2013 for an introduction), we will use general consumption (C) and investment (I) functions that depend on income (Y), and the functional distribution of income measured by the wage share (WS):

Consumption depends positively on income (∂C/∂Y>0) (to simplify the discussion, we will here drop time subscripts and assume instantaneous effects, whereas in the empirical analysis we will consider lagged effects). Following a long tradition in classical and post-Keynesian theory, we assume that the marginal propensity to consume is higher for workers (or recipients of wage incomes) than for capitalists (or recipients of capital incomes). Thus, a higher wage share will positively affect consumption (∂C/∂WS > 0). Mainstream (neoclassical) economics does not usually attribute much importance to the distribution of income function in its consumption theory, but the fact that the rich have higher lower marginal propensity to consume than the poor is widely accepted, thus this equation is not necessarily in contradiction to standard theory.

The investment function:

depends on income, the wage share and the (real) rate of interest (i). There is little disagreement that income will have positive effects on investment. The accelerator hypothesis claims that the change in demand will affect (the level of) investment; in the empirical analysis we will return to this issue. While the investment function here is, for simplicity, formulated as the relationship between levels, in the empirical analysis we use an error correction model (ECM) specification, which includes level as well as differences and thus allows the discussion of accelerator effects. If firms are credit constrained, then higher profits will allow firms to investment more. Additionally, firms may interpret current profits as predictor of future profits.

Exports, X, are a positive function of foreign demand, Z, the wage share and the exchange rate, E. The wage share is regarded as a proxy for unit labour costs and, assuming that higher labour costs are passed on to export prices, competitiveness:

Similarly, imports, M, are a positive function of domestic demand, the wage share and the nominal exchange rate:

Aggregate expenditures equal consumption, investment, net exports (NX = X−M) and government consumption (G):

Bhaduri and Marglin (Citation1990) proposed a general macroeconomic framework that allows for wage-led as well as profit-led demand regimes. This has become an important point for post-Keynesian macroeconomics because it includes the Kaleckian consideration, with consumption demand coming from workers’ income, as well as the central role of profitability for investment in classical economics.

In this paper, like much of the literature, we take government expenditures as exogenously given. Differentiating equilibrium income, Y*, with respect to the wage share gives:

The numerator of this equation, h2, is the partial effect of a change in distribution on the domestic demand components, which is also called private excess demand: the increase in demand due to a distributive change for a given level of income. The denominator

is similar to a standard multiplier but includes investment effects. It measures the second-round effects of changes in distribution. Assuming that the multiplier is positive, the sign of the total effect of a change in income distribution will depend on the sign of the effect on excess demand, i.e. h2. The overall distributive dynamics of the economy will be determined by the relative strength of consumption and investment responses to higher wage shares. If higher consumption more than outweighs the reduction of investment due to lower profit margins, the economy as a whole will be wage-led

. In the reverse case it will be profit-led

.

A string of studies follow that of Bhaduri and Marglin, judging whether economies have wage-led or profit-led growth regimes (Naastepad and Storm Citation2006; Hein and Vogel Citation2008; Stockhammer, Onaran, and Ederer Citation2009; Stockhammer and Stehrer Citation2011; Onaran and Galanis Citation2014). For the postwar period, the majority of studies find wage-led domestic demand regimes in almost all countries, with the Anglo-Saxon countries sometimes an exception. However, net exports can make some economies become profit-led regimes. The size of this effect depends, critically, on the degree of openness, i.e. how large is the economy’s dependence on exports.

Demand regimes measure the effect of a one-unit change in income distribution on aggregate demand. While the original Bhaduri–Marglin model focuses on these demand effects, there is a rich tradition in post-Keynesian economics of emphasising that changes in functional income distribution also have supply-side effects. The Kaldor–Verdoorn relation postulates that higher wage growth can lead to higher productivity growth as it creates an incentive for firms to upgrade production processes. Storm and Naastepad (Citation2013) have integrated this mechanism in the Bhaduri–Marglin model. Productivity growth is thus modelled as a positive function of the wage share and a positive function of output growth, which captures dynamic returns to scale:

Again, for simplicity we present the equation here without time subscripts; in the empirical analysis, the right-hand side variables will be lagged. We note that, on the mainstream side, similar arguments on productivity have been suggested. In particular, efficiency wage models (Akerlof Citation1982; Shapiro and Stiglitz Citation1984) imply that higher wage growth implies a positive effect of wages on productivity as it elicits greater work effort. Naastepad (Citation2006) argues, in a case study of the Netherlands, that an important cause of the post-1980 productivity slowdown was the decline in wage pressure. According to Naastepad, this lies behind the Dutch ‘employment miracle’: lower wages, less productivity, more jobs (cf. Hein and Tarassow Citation2010). This argument is very interesting in our context too because the Scandinavian countries also experienced a period of growing wage shares during the postwar years and then a fallback after 1980. It also corresponds with the Swedish wage bargaining model developed in the postwar period, the Rehn–Meidner model (Erixon Citation2008, Citation2011, Citation2018), which will be discussed in the next section.

A limitation of this paper must be noted. We are interested in the nature of the demand and productivity growth regimes and thus take the wage share as given; in other words, the wage share is determined exogenously. Intuitively, this is plausible if we regard the wage share as determined by changes in the market power of firms, the bargaining position of labour and the degree of financialization (Kalecki Citation1965; Hein Citation2015; Stockhammer Citation2017). However, in particular in the short run, the wage share will, in fact, also be influenced by the level of aggregate demand if there are fixed costs (Kalecki Citation1965, ch. 2) or if prices are more flexible than wages. To avoid endogeneity problems, the empirical analysis will use lagged values of the wages share as instruments. Our study thus needs to be complemented with a systems approach that allows for an endogenous determination of the wage share (e.g. Stockhammer and Onaran Citation2004; Jump and Mendieta-Munoz Citation2017). However, this is outside the scope of the present paper.

3. Empirical and historical context: Scandinavia in the 20th century

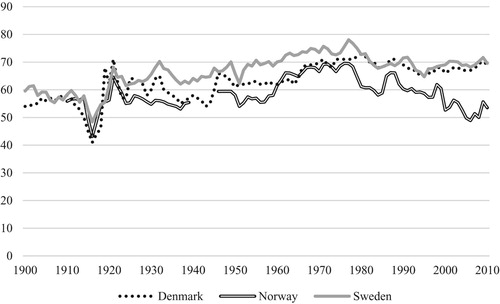

Why is it interesting to extend the application of the Bhaduri–Marglin model to the past? We argue that there are two especially salient reasons. First, the past provides interesting variations in the variables that we are interested in, such as the wage share. As shows, substantial fluctuations in the wage share occurred during the interwar and postwar periods. Thus, there is greater variance in that data than there is in data for more recent periods, and the latter have been more widely used for macroeconomic research. In Denmark and Norway, the wage share fell during the 1930s and 1940s, while it was stable in Sweden. In the postwar period the wage share grew, continuously in Denmark and Sweden and more suddenly circa 1960 in Norway. It peaked around 1980 and thereafter declined.

Figure 1. Wage shares, 1900–2010. Sources: Abildgren (Citation2008) and AMECO for Denmark, Bengtsson and Waldenström (Citation2018) for Norway and Edvinsson (Citation2005) and AMECO for Sweden.

Second, the economic history literature contains many arguments on the interconnection of labour–capital distribution and economic performance, but these arguments have been made in very different theoretical contexts. Implicitly, they assume a profit-led demand regime and do not take the comprehensive view represented by the Bhaduri––Marglin model and its extensions.

Let us tackle the historical context and the economic history literature together. Many economic historians have worked from a more or less neoclassical framework and considered the wage share foremost as an indicator of wage pressure and the costs faced by companies. In this view, growing wage shares have been harbingers of a dearth of investment, causing low GDP growth and higher unemployment, as in the case of interwar Britain and Germany (Broadberry and Ritschl Citation1995) or interwar Norway (Nordvik and Grytten Citation1994). Conversely, in influential analyses of the postwar economic miracle in Western Europe, Barry Eichengreen and others have emphasized the role of union–employer–government collaboration and voluntary wage restraint in holding back wages, and thereby increasing investment and growth (Eichengreen and Vazquez Citation1999; Eichengreen Citation2007). Scandinavia has been especially singled out as comprising corporatist countries in which wage restraint improved economic performance in the 1950s and 1960s (e.g. Pekkarinen Citation1992; Vartiainen Citation1998; Alexopoulos and Cohen Citation2003; see discussion in Bengtsson Citation2015).

Among the economic historians, unlike among the post-Keynesians, the convention is to assume that a growth in the wage share first and foremost has a negative effect on economic performance (but see van Zanden (Citation2000) and Bengtsson (Citation2015) for exceptions). In the postwar literature, the argument that wage restraint was present and good for growth is often made without any econometric investigation at all, as pointed out by Hatton and Boyer (Citation2005, p. 43). However, Eichengreen and Vazquez (Citation1999, Table 9), in an unpublished work, do present econometric evidence that the wage share had a negative effect on investment in postwar Europe. In Eichengreen’s (Citation2007, p. 86) analysis, investments and international trade were the two major drivers of the great postwar growth experience, which does direct attention to the effects of wages on exports and investment.

In the economic history literature, consideration is also given to the wage push–productivity connection, as discussed in relation to Naastepad and Storm in the previous section. Low wage growth might stimulate employment growth, as in Dimsdale, Nickell, and Horsewood (Citation1989), but it might result in low productivity jobs, with little incentive for rationalization. Temin (Citation1990, p. 301) thus argues that low real wage growth in Nazi Germany between 1932 and 1937 stimulated employment growth but not productivity growth, while New Deal-strengthened real wages in the US in the same period improved both productivity and competitiveness.

Interestingly, there is another field of literature on Scandinavia in the postwar period, which sees the relationship between the wage share and economic performance in a very different light to that propounded by the economic history literature discussed so far. This is the literature on wage policy by labour historians (Ekdahl Citation2001) and economists with an interest in post-Keynesianism (Erixon Citation2008, Citation2011, Citation2018). In 1951, the Swedish Trade Union Confederation, commonly referred to as LO, supported a coordinated and ‘solidaristic’ wage policy in which wages would be equalized, inflation-fighting would be handled by strict fiscal policy (not by wage policy) and unemployment would be managed by active labour market policies. It suggested that wages should be pushed up and equalized. This followed LO economists Gösta Rehn and Rudolf Meidner’s analysis of the macroeconomy, and Erixon (Citation2018) stresses the overlap between the Rehn–Meidner model of Sweden in the 1950s and 1960s and Kaldorian and Kaleckian models. Rehn and Meidner argued that large profits were inflationary, by stimulating wage–wage spirals, and harmful for productivity, as they allowed less productive firms to survive. Wage pressure from the unions should therefore push down profits. Erixon (Citation2018, p. 664) argues that, ‘Rehn and Meidner wanted to replace (or at least control) a demand- and profit-led economic development by a strategy that can be classified as wage-led and demand-restricting. … [T]he model is an example of progressive supply-side economics.’ Norway developed similar models in the 1950s, while Danish wage bargaining was less theory-guided.

Earlier literature on the growth performance of Scandinavian economies since 1945 does not consider the possible effects of a changing capital–labour income distribution. For example, Henrekson, Jonung, and Stymne (Citation1996) discussed the postwar growth experience of Sweden, which, they argued, from the 1970s onwards was affected by Eurosclerosis resulting from high taxes and welfare state generosity. Sweden had a very strong growth experience in the 1950s and 1960s, while Denmark and Norway, which had been occupied by Germany during the Second World War, experienced slower starts (Johansen Citation1987, ch. 7; Eichengreen Citation2007). Sweden experienced extremely strong economic development in the postwar decades (Schön Citation2014, pp. 325–327). A common view is that industrial expansion caused high growth rates in the postwar period but that, in the transition to a service economy after the oil crisis of 1973, Sweden’s growth performance was hampered by a too generous welfare state (Bergh Citation2014). Karanassou, Sala, and Salvador (Citation2008) demonstrate the importance of capital investment for unemployment in the Nordic countries. Storm and Naastepad (Citation2012, pp. 197–201) are unique in providing a post-Keynesian analysis of Nordic growth. However, they analyse only (five-year averages of) the years 1984–2004. Thus, their analysis is an important predecessor to this paper but lacks the historical interest we demonstrate here.

4. Data and empirical analysis

Following the discussion in Section Two, we now investigate the effects of changing labour–capital distribution (the wage share) on consumption, investment, exports, imports and labour productivity.

To identify the appropriate time series specification, we first test for cointegration by estimating ECMs. We use the critical values of Banerjee, Dolado, and Mestre (Citation1998), but regard cointegration as plausible if a coefficient estimate for the error correction term shows a t-value of 3 or above. When we fail to find evidence for cointegration, we estimate distributed lag models in first difference form. For all cases, we choose specifications based on the Akaike and Bayesian Information Criteria. We test models with one, two and three lags and choose the best-fitting specifications based on the information criteria, so long as they do not suffer from autocorrelation. The third lag very rarely exerts an effect, and the finding that effects of the wage share on consumption, productivity and our other dependent variables typically fade out in one to three years conforms with the previous literature (cf. Stockhammer, Onaran, and Ederer Citation2009; Hein and Tarassow Citation2010). We exclude contemporaneous effects to avoid endogeneity issues. All variables involved, except the interest rate, are in logarithm form. Consumption, investment, exports, imports and GDP are all measured in constant prices.

For consumption, the full ECM regression estimated is:

(1)

(1) where C is consumption in real prices, Y is GDP in real prices and WS is the wage share. When we do not find evidence for cointegration, the first difference regression estimated is:

(1b)

(1b) For investment, the model is the same but with the real interest rate included among the independent variables. As ECM specifications include levels as well as differences, the equation does include an accelerator effect:

(2)

(2) where INT is the real interest rate.

For exports, the model is as follows:

(3)

(3) where Z is a proxy for foreign demand and E is the exchange rate vis-à-vis the currencies of the five most important trade partners of the economy. Exports are a function of both the wage share and the exchange. As the exchange rate may also affect the wage share, the resulting multicollinearity may make it difficult to identify the exact impact of the two variables econometrically.

Productivity is heavily autocorrelated and we use first-difference models with a lagged, differenced dependent variable. The labour productivity equation is as follows:

(4)

(4) where P is labour productivity, as output (in real prices) per worked hour, or per worker, depending on data availability. Because of the long time span, year dummies will also be used for those years during the world wars when other forces heavily influenced GDP components. During the world wars all macroeconomic variables were affected by special conditions in peculiar ways, which makes it important to use year dummies for some of these years. It is also standard practice in long-run time series econometrics (e.g. Castle and Hendry Citation2009).

The postwar years are considered a special period in European economic history (cf. Eichengreen Citation2007), and we will explore whether the relationship between the wage share and economic performance was indeed different then in comparison to years before or after. For this reason, we explore specific postwar effects by including interactions with postwar (1945–73) time dummies. For simplicity, we consider only interactions with the wage share variable. We also conduct calculations with corresponding sub-samples; however, doing so steeply decreases the degrees of freedom. For this reason, we prefer period dummy interactions to explore period-specific effects.

4.1. Data

We apply the models discussed above to data for Denmark, 1900–2010, Norway, 1910–2010, and Sweden, 1900–2010.Footnote1 The data thus covers the interwar and postwar periods discussed in Section Two, as well as the post-1980 period with a quite different wage formation pattern (Hatton and Boyer Citation2005; Bengtsson Citation2015). The long-run datasets that we use build on recent historical national accounts research, not least that conducted under the auspices of central banks. GDP and its components (consumption, investment, exports and imports) are gathered from Kaergård (Citation1991) and Statistics Denmark for Denmark, Grytten (Citation2004) for Norway, and Krantz and Schön (Citation2015) for Sweden. The wage share is the adjusted wage share of GDP, i.e. including imputed labour incomes of the self-employed. Wage shares are taken from Abildgren (Citation2008) for Denmark, Bengtsson and Waldenström (Citation2018) for Norway and Edvinsson (Citation2005) for Sweden; in the Danish and Swedish cases, we link the historical estimates with those from the European Commission’s Annual Macroeconomic database, AMECO, for recent years. To measure export conditions, we measure trade partners’ GDP growth, which is a proxy for foreign demand (Z in the export equation). For this, we take the five largest export destinations of the country in question and the GDP growth of each of those five countries in a given year and then calculate trade share-weighted partners’ GDP growth. Trade partners’ GDP growth is calculated using Maddison Project Database (Citation2013), Abildgren (Citation2008), Grytten (Citation2004), Edvinsson (Citation2005), and Hills et al. (Citation2015) and trade shares from Abildgren (Citation2010, Table A3.1), SSB (Citation1968, Tables 152, 164) and SCB (Citation1972, p. 298). The exchange rate is that between the country’s currency and a basket of currencies, typically those of the country’s main trading partners.Footnote2 They are taken from Abildgren (Citation2005), Klovland (Citation2004) and Bohlin (Citation2010). Interest rates are taken from Abildgren (Citation2006), Eitrheim and Klovland (Citation2007) and Waldenström (Citation2014) For Sweden, the labour productivity variable is real value added per employee taken from Krantz and Schön (Citation2015); for Norway, it is real output per hour taken from Bore and Skoglund (Citation2008); and, for Denmark, it is real output per hour taken from Abildgren (Citation2008, Table A6).

This study builds on annual data. Some investigations of more recent periods use quarterly data. This approach is helpful but not possible in the historical context whereby such data is not available.

5. Results

5.1. Distribution and growth in Scandinavia

We begin with the archetypical example of social democracy and social democratic wage bargaining institutions in Sweden (Vartiainen Citation1998; Alexopoulos and Cohen Citation2003). We find neither cointegration for consumption nor investment. Therefore, we use first-difference models. The information criteria for consumption suggest models with two or three lags (, columns 1 and 2). The wage share (t−2) has a statistically significant positive effect on consumption, 0.30–0.32. As both variables are in logarithms, this indicates that a 1-percentage point increase in the wage share would increase consumption by 0.32 per cent. We prefer the first specification, as adding the third lag does not improve the model fit and results are qualitatively similar.

Table 1. Consumption and investment in Sweden.

The effects on investment of the wage share (columns 3, 4 and 5) are only statistically significant when we include one lag of the explanatory variables. In the fuller models, there is no statistically significant effect of the wage share. We prefer the specification with three lags as its fit is best according to the information criteria. We fail to find significant period-specific effects, so those results are not reported here.

The results for Swedish exports and imports are shown in . Neither exports nor imports are cointegrated, so we report first-difference results, with three lags for exports and two for imports; adding more does not improve the fit. For exports, the best-fitting models, according to the information criteria, are those with three lags. Swedish exports are steered heavily by trade partners’ demand, as proxied by their GDP growth. Last year’s trade partners’ GDP growth has an effect of 0.88; adding the other two lags raises the total effect to unity. A depreciation of the exchange rate does not have significant effects. The wage share surprisingly has an appositive effect, of 0.49 in the best-fitting model.

Table 2. Exports and imports in Sweden.

We find Danish consumption and investment to be not cointegrated, so reports first-difference results. In our preferred lag structure with two lags (column 1), the wage share increases consumption by 0.22. The effect of the wage share on consumption does not seem to vary over time.

Table 3. Consumption and investment in Denmark.

While the wage share increases consumption, as expected it hurts investment (columns 3–5). The estimated negative effect of wage share growth varies between −0.94 and −1.26, depending on the specification. While the postwar dummy interaction (column 5) does not reach statistical significance at the 10 per cent level, the results are indicative. They suggest that, in the postwar period, the wage share had a very weakly negative effect on investment: while the coefficient for the wage share t−1 is −1.08, the coefficient for the interaction is 1.04. The composite effect in the postwar period would then be only −0.04. These results correspond very well with the finding of Hatton and Boyer (Citation2005) that wage pushes in postwar Britain had no negative effect on employment, while post-1980 they had rather large negative effects.

presents results for exports and imports in Denmark. We find no cointegration, and first-difference models with one or one and two lags are presented. In both cases, the model with two lags fits better in terms of AIC and BIC, and has fewer problems with autocorrelation, so these (columns 2 and 4) are the ones that we use. As expected, trade partners’ GDP growth exerts strong effects on Danish exports; in model 2, the positive effect of last year’s growth is 1.37. However, the second lag has a negative effect. The effect of the wage share is negative (−0.93) and significant in specification one, but slightly positive in specification two, 0.51. Effects are no different in the postwar period than overall.

Table 4. Exports and imports in Denmark.

For Norwegian consumption, we do not find cointegration, so report first-difference models. Investment, on the other hand, is cointegrated and in that case we report error correction models. contains the models with the best fit according to the information criteria. The results indicate that the wage share has a weakly positive effect on consumption, 0.14. The positive effect is nullified in the post-1980 period, as reported in column 4; on the other hand, there is no specific period effect in the postwar period. We report the investment results in columns 5 and 6. There is no significant effect of the wage share on investment, and no time-varying effects.

Table 5. Consumption and investment in Norway.

Norwegian exports are not cointegrated, so we use first-difference models. The export growth equation shows strong autocorrelation, so we include two lags of the dependent variable. We also experiment with specifications with three lags, but the third lag does not add explanatory value. Our specification of choice is the first-difference specification with one lag, presented in column 2 of . We find, as expected, that a depreciation of the currency exchange rate is associated with more exports, while trade partners’ growth surprisingly has no statistically significant effect. The effect of the wage share is also surprising as it is positive, 0.36. Columns 3 and 4 allow for period-specific effects, including period interactions with a postwar dummy and a post-1980 dummy. These show that the positive estimated effect of the wage share on exports is driven in particular by the postwar period, in which we get a statistically significant coefficient of 0.55. After 1980 the effect is negative, at −0.74, which, after we subtract the average positive effect of 0.64, leaves a net negative effect of −0.10. The results for imports — columns 5 and 6 in — are unremarkable. Imports are primarily driven by GDP growth; the exchange rate does not have a significant effect.

Table 6. Exports and imports in Norway.

5.2. Labour productivity

So far, we have only considered the demand side. What about the supply side and the effects of wage–capital distribution on labour productivity? Have growing wage shares pushed productivity up, as suggested by both the postwar Swedish Rehn–Meidner model (Erixon Citation2011) and post-Keynesian models (Storm and Naastepad Citation2012)? To investigate the effects of wages on labour productivity, we use first-difference specifications. To avoid reverse causality issues, we use models with lagged explanatory variables only and experiment with up to three lags. The results, summarized in , are strikingly similar across the countries studied. A 1-percentage point increase in the wage share increases productivity growth by approximately 0.2 per cent in Sweden, 0.3 per cent in Denmark and 0.4 per cent in Norway. In all cases, these effects are statistically significant at the 5 per cent level or higher. The lag structure differs, with effects materializing within one year in Norway and Denmark but two years in Sweden.

Table 7. Productivity in Sweden, Denmark, and Norway.

The results are very much in line with Marx–Hicks wage-led productivity arguments, such as those in Storm and Naastepad (Citation2012). We should note that the productivity measure used in Sweden is less precise: output per employee rather than output per worked hour. However, the results are very similar to those for Denmark and Norway.

5.3. Summary of weighted results

brings together results for the distributional effects on demand. Here, the coefficients from our preferred specifications are weighted by their shares of GDP related to consumption, investments and exports. In all three countries we find weakly wage-led growth regimes. What is common is positive effects of the wage share on consumption, surprising positive effects on exports, and negative or neutral effects on investments. To clarify: in Sweden, our benchmark specification is that a one-point increase in the wage share increases consumption by 0.30 and decreases investment by −0.40. Exports increase by 0.49. When we consider the relative roles of C, I and X in GDP growth, a one-point increase in the wage share boosted growth by 0.31 per cent in Sweden during 1900–2010, so growth was weakly wage-led. For Denmark, according to our preferred specifications, a one-point increase in the wage share in total for the period 1900–2010 had a weakly positive effect on demand, +0.10 per cent. In the postwar period, due to the smaller negative effect on investment, the wage-led character of growth was slightly stronger, +0.27. In Norway, the growth regime was weakly wage-led: a 1-percentage point increase in the wage share increased growth by 0.17 points, and, in the postwar period, by 0.19 points. The finding of wage-led growth accords well with Storm and Naastepad’s (Citation2012) investigation of the post-1980 experience. The lack of more negative effects on exports is striking for these small open economies, but correspond to Baccaro and Pontusson’s (Citation2016) finding of strikingly weak wage effects on exports in Sweden in the post-1994 period.

Table 8. Demand effects of a one-point increase in the wage share.

What do our results, taken together, imply for interpretation of the Scandinavian growth experience? One thing is clear, our results contrast with the mainstream account of the postwar ‘golden age’ of growth, an epoch of wage restraint in corporatist countries such as those comprising Scandinavia (Alexopoulos and Cohen Citation2003; Eichengreen Citation2007). In fact, as we saw in , wages grew faster than productivity in Scandinavia in the postwar period, which meant that wage shares grew. This did not harm economic performance — on the contrary, following our results, growing wage shares had, instead, weakly positive effects on growth. But we cannot say that wage-led growth was the most important determinant of growth. Other factors such as policies, innovations and public investments also mattered (cf. Johansen Citation1987; Henrekson, Jonung, and Stymne Citation1996; Schön Citation2014; Bergh Citation2014).

6. Conclusion

Our investigation has shown the usefulness of macroeconomic models of the distribution–growth nexus that allow for the investigation of different, historical, demand regimes. When we consider not only the effect of wages as a cost for companies, hampering profitability and investments, and possibly exports, but also the implications of wages for consumption demand and productivity growth, we can question some crucial assumptions in the economic history literature. For the classic corporatist economies of Scandinavia, our results contrast with the standard economic history narrative of wage restraint having facilitated rapid economic growth in the postwar period through the channel of increasing investment (Eichengreen Citation1994, Citation2007; Moene and Wallerstein Citation1995; Alexopoulos and Cohen Citation2003). Instead, our findings of wage-led demand and wage-led productivity accord with those of Storm and Naastepad (Citation2012, pp. 197–205), who identified wage-led demand in the Nordic countries from the 1980s onwards. The results also provide the first econometric evidence for the growth effects of the postwar Rehn–Meidner model in Sweden, which has been a major discussion point for both labour historians (Ekdahl Citation2001; Johansson and Magnusson Citation2012) and post-Keynesians (Erixon Citation2008, Citation2011, Citation2018). It has previously been shown that the Rehn–Meidner model in Sweden speeded up structural transformation, reshuffling workers from low-pay to high-pay industries (Davis and Henrekson Citation2005); our investigation concludes that this wage policy also had a positive effect on labour productivity.

The present investigation opens up several avenues for further research. This is the first quantitative investigation of the distribution–growth nexus in Scandinavia over the long run, and the approach can be refined in several ways. As discussed above, one way forward would be to integrate analysis of the determinants of labour–capital distribution with analysis of the effects of distribution on growth. This would require a systems approach that allows for an endogenous determination of the wage share (cf. Stockhammer and Onaran Citation2004; Jump and Mendieta-Munoz Citation2017).

Another way forward, related to the first, would be to undertake a more detailed investigation of the connection between wage bargaining systems, such as the Rehn–Meidner model, and productivity and growth. A promising strategy would be to integrate a sectoral approach and a focus on structural transformation with the macro estimates of labour productivity performed here; a sector-level approach would allow for greater understanding of the causal mechanisms in play and how wage setting really affected economic performance.

A third way forward would be to integrate the development of wage shares in main trading partner countries, to gain an international perspective on the distribution–growth nexus. The Scandinavian countries are small, open, export-dependent economies and so it is slightly surprising that the effects of the wage share on exports are not stronger than those we found. But perhaps one explanation is that trade partners experienced similar movements in wage shares. As Scott and Spadavecchia (Citation2011) point out, the eight-hour work day reform enacted in Britain in 1919 increased hourly wages significantly and so had a negative effect on export competitiveness; however, since most of Britain’s trade partners enacted similar reforms at the same time, the net effect on British competitiveness was zero or close to zero. This point might be generalizable to other time periods as well, not least the postwar period when wage shares grew in all OECD countries (Bengtsson and Waldenström Citation2018).

Finally, a fourth development of the present paper would be to integrate public investment and the role of the public sector in attempts to understand the growth experience of the Scandinavian countries as well as other welfare states. In highly interventionist economies such as those of the Scandinavian countries — and in the postwar period, more or less all capitalist economies — profit rates are not the only consideration relevant for investment decisions, as much of investment is actually either publicly financed, publicly directed or both. Especially for Norway, we found very low shares of private consumption in GDP, and an internationally high level of public consumption. Further research should thus distinguish between private and public investment and nuance our understanding of the relation between labour–capital distribution and investment and overall economic growth.

Acknowledgements

This paper has been presented at Kingston University in the UK and Lund University in Sweden; thanks to all the participants and to Erik Hegelund for helpful comments. Thank you to two anonymous referees and the editor, Louis-Philippe Rochon, for constructive suggestions that helped to improve the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In Denmark, there are two gaps in the macroeconomic data: 1915–20 and 1940–46. In the Norwegian data, there is one gap: 1940–45.

2 With the exchange rates, it is important to note whether they are coded so that an increase in the index means an appreciation or depreciation. For Norway and Sweden, an increase means depreciation. For Denmark, in contrast, an increase means appreciation of the DKK against a basket of currencies.

References

- Abildgren, K. 2005. ‘Real Effective Exchange Rates and Purchasing-Power-Parity Convergence: Empirical Evidence for Denmark, 1875–2002.’ Scandinavian Economic History Review 53 (3): 58–70.

- Abildgren, K. 2006. ‘Monetary Trends and Business Cycles in Denmark 1875–2005 – New Evidence Using the Framework of Financial Accounts for Organising Historical Financial Statistics.’ Danmarks Nationalbank Working Papers 2006: 43. Copenhagen: Danmarks Nationalbank.

- Abildgren, K. 2008. ‘Are Labour Market Structures Endogenously Dependent on the Monetary Regime? Empirical Evidence from Denmark 1875–2007.’ Danmarks Nationalbank Working Papers 2008:52. Copenhagen: Danmarks Nationalbank.

- Abildgren, K. 2010. Quantitative Studies on the Monetary and Financial History of Denmark. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen.

- Akerlof, G. A. 1982. ‘Labor Contracts as Partial Gift Exchange.’ Quarterly Journal of Economics 97 (4): 543–569.

- Alexopoulos, M., and J. Cohen. 2003. ‘Centralised Wage Bargaining and Structural Change in Sweden.’ European Review of Economic History 7 (3): 331–366.

- AMECO. ‘The Annual Macroeconomic Database of the European Commission.’ Accessed April 24, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/indicators-statistics/economic-databases/macro-economic-database-ameco_en.

- Baccaro, L., and J. Pontusson. 2016. ‘Rethinking Comparative Political Economy: The Growth Model Perspective.’ Politics and Society 44 (2): 175–207.

- Banerjee, A., J. J. Dolado, and R. Mestre. 1998. ‘Error-correction Mechanism Tests for Cointegration in a Single-Equation Framework.’ Journal of Time Series Analysis 19 (3): 267–283.

- Bengtsson, E. 2015. ‘Wage Restraint in Scandinavia: During the Postwar Period or the Neoliberal Age?’ European Review of Economic History 19 (4): 359–381.

- Bengtsson, E., and D. Waldenström. 2018. ‘Capital Shares and Income Inequality: Evidence from the Long Run.’ Journal of Economic History 71 (3): 712–743.

- Bergh, A. 2014. ‘What Are the Policy Lessons from Sweden? On the Rise, Fall and Revival of a Capitalist Welfare State.’ New Political Economy 19 (5): 662–694.

- Bhaduri, A., and S. Marglin. 1990. ‘Unemployment and the Real Wage: The Economic Basis for Contesting Political Ideologies.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 14 (4): 375–393.

- Bohlin, J. 2010. ‘From Appreciation to Depreciation – The Exchange Rate of the Swedish Krona, 1913–2008.’ In Exchange Rates, Prices, and Wages, 1277–2008: Historical Monetary and Financial Statistics for Sweden, edited by R. Edvinsson, T. Jacobson, and D. Waldenström. Stockholm: Ekerlids förlag.

- Bore, R. R., and T. Skoglund. 2008. Fra Håndkraft til Høyteknologi – Norsk Industri Siden 1829. Oslo: Statistisk Sentralbyrå.

- Broadberry, S. N., and A. Ritschl. 1995. ‘Real Wages, Productivity, and Unemployment in Britain and Germany During the 1920s.’ Explorations in Economic History 32 (3): 327–349.

- Castle, J., and D. Hendry. 2009. ‘The Long-Run Determinants of UK Wages, 1860–2004.’ Journal of Macroeconomics 31 (1): 5–28.

- Davis, S. J., and M. Henrekson. 2005. ‘Wage-Setting Institutions as Industrial Policy.’ Labour Economics 12 (3): 345–377.

- Dimsdale, N., S. J. Nickell, and N. Horsewood. 1989. ‘Real Wages and Unemployment in Britain During the 1930s.’ The Economic Journal 99 (June): 271–292.

- Edvinsson, R. 2005. Growth, Accumulation, Crisis: With New Macroeconomic Data for Sweden 1800–2000. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Eichengreen, B. 1994. ‘Institutional Prerequisites for Economic Growth: Europe After World War II.’ European Economic Review 38 (3-4): 883–890.

- Eichengreen, B. 2007. The European Economy Since 1945: Coordinated Capitalism and Beyond. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Eichengreen, B., and T. Iversen. 1999. ‘Institutions and Economic Performance: Evidence from the Labour Market.’ Oxford Review of Economic Policy 15 (4): 121–138.

- Eichengreen, B., and P. Vazquez. 1999. Institutions and Economic Growth in Postwar Europe: Evidence and Conjectures. Mimeo: University of California, Berkeley.

- Eitrheim, Ø., and J. T. Klovland. 2007. ‘Short Term Interest Rates in Norway 1818–2007.’ In Historical Monetary Statistics for Norway – Part II, edited by Ø. Eitrheim, J. T. Klovland, and J. F. Qvigstad. Oslo: Norges Bank.

- Ekdahl, L. 2001. Mot en Tredje Väg: En Biografi över Rudolf Meidner. I: Tysk Flykting och Svensk Modell. Lund: Arkiv.

- Erixon, L. 2008. ‘The Swedish Third Way: An Assessment of the Performance and Validity of the Rehn-Meidner Model.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 32 (3): 367–393.

- Erixon, L. 2011. ‘A Social Innovation or a Product of Its Time? The Rehn-Meidner Model’s Relation to Contemporary Economics and the Stockholm School.’ European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 18 (1): 85–123.

- Erixon, L. 2018. ‘Progressive Supply-Side Economics: An Explanation and Update of the Rehn-Meidner Model.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 42 (3): 653–697.

- Grytten, O. H. 2004. ‘The Gross Domestic Product for Norway 1830–2003.’ In Historical Monetary Statistics for Norway 1819–2003, edited by Ø. Eitrheim, J. T. Klovland, and J. F. Qvigstad. Oslo: Norges Bank.

- Hatton, T., and G. Boyer. 2005. ‘Unemployment and the UK Labour Market Before, During and After the Golden Age.’ European Review of Economic History 9 (1): 35–60.

- Hein, E. 2015. ‘Finance-Dominated Capitalism and Re-Distribution of Income: A Kaleckian Perspective.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 39 (3): 907–934.

- Hein, E., and A. Tarassow. 2010. ‘Distribution, Aggregate Demand and Productivity Growth: Theory and Empirical Results for Six OECD Countries Based on a Post-Kaleckian Model.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 34 (4): 727–754.

- Hein, E., and L. Vogel. 2008. ‘Distribution and Growth Reconsidered: Empirical Results for Six OECD Countries.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 32 (3): 479–511.

- Henrekson, M., L. Jonung, and J. Stymne. 1996. ‘Economic Growth and the Swedish Model.’ In Economic Growth in Europe Since 1945, edited by N. Crafts and G. Toniolo. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hills, S., R. Thomas, and N. Dimsdale. 2015. ‘The UK recession in context – what do three centuries of data tell us? Data Annex - Version 2.2, July 2015.' Accessed March 21, 2017. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/research-datasets.

- Johansen, H. C. 1987. The Danish Economy in the Twentieth Century. London: Croom Helm.

- Johansson, A. L., and L. Magnusson. 2012. LO: 1900-talet och ett Nytt Millennium. Stockholm: Atlas.

- Jump, R., and I. Mendieta-Munoz. 2017. ‘Wage Led Aggregate Demand in the United Kingdom.’ International Review of Applied Economics 31 (5): 565–584.

- Kaergård, N. 1991. Økonomisk Vækst: En Økonometrisk Analyse af Danmark 1870–1981. Copenhagen: Jurist- og Økonomforbundets Forlag.

- Kalecki, M. 1965. Theory of Economic Dynamics. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Karanassou, M., H. Sala, and P. F. Salvador. 2008. ‘Capital Accumulation and Unemployment: New Insights on the Nordic Experience.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 32 (6): 977–1001.

- Katzenstein, P. J. 1985. Small States in World Markets: Industrial Policy in Europe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Klovland, J. T. 2004. ‘Historical Exchange Rate Data 1819–2003.’ In Historical Monetary Statistics for Norway 1819–2003, edited by Ø. Eitrheim, J. T. Klovland, and J. F. Qvigstad. Oslo: Norges Bank.

- Krantz, O., and L. Schön. 2015. ‘New Swedish Historical National Accounts since the 16th Century in Constant and Current Prices.’ Lund Papers in Economic History No. 140. Lund: Department of Economic History.

- Lavoie, M., and E. Stockhammer. 2013. ‘Introduction.’ In Wage-Led Growth: An Equitable Strategy for Economic Recovery, edited by M. Lavoie and E. Stockhammer. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Maddison Project Database. 2013. 'Historical Statistics of the World Economy: 1—2008 AD.', version 2013. Accessed February 15, 2019. https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/.

- Moene, K. O., and M. Wallerstein. 1995. ‘How Social Democracy Worked: Labor-Market Institutions.’ Politics and Society 23 (2): 185–211.

- Naastepad, C. W. M. 2006. ‘Technology, Demand and Distribution: A Cumulative Growth Model With an Application to the Dutch Productivity Growth Slowdown.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 30 (3): 403–434.

- Naastepad, C. W. M., and S. Storm. 2006. ‘OECD Demand Regimes (1960–2000).’ Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 29 (2): 213–248.

- Nordvik, H. W., and O. H. Grytten. 1994. ‘The Labour Market, Unemployment and Economic Growth in Norway, 1920–1939.’ Scandinavian Economic History Review 42 (2): 125–144.

- Onaran, Ö., and G. Galanis. 2014. ‘Income Distribution and Growth: A Global Model.’ Environment and Planning 46 (10): 2489–2513.

- Pekkarinen, J. 1992. ‘Corporatism and Economic Performance in Sweden, Norway, and Finland.’ In Social Corporatism: A Superior Economic System?, edited by J. Pekkarinen, M. Pohjola, and B. Rowthorn. Oxford: Clarendon.

- SCB. 1972. Historisk Statistik för Sverige. Del 3: Utrikeshandel 1732–1970. Stockholm: National Central Bureau of Statistics.

- Schön, L. 2014. En Modern Svensk Ekonomisk Historia. 4th ed. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Scott, P., and A. Spadavecchia. 2011. ‘Did the 48-Hour Week Damage Britain’s Industrial Competitiveness?’ Economic History Review 64 (4): 1266–1288.

- Shapiro, C., and J. E. Stiglitz. 1984. ‘Equilibrium Unemployment as a Worker Discipline Device.’ American Economic Review 74 (3): 433–444.

- SSB. 1968. Historisk Statistikk 1968. Oslo: Central Bureau of Statistics of Norway.

- Stockhammer, E. 2017. ‘Determinants of the Wage Share: A Panel Analysis of Advanced and Developing Economies.’ British Journal of Industrial Relations 55 (1): 3–33.

- Stockhammer, E., and O. Onaran. 2004. ‘Accumulation, Distribution and Employment: A Structural VAR Approach to a Kaleckian Macro-Model.’ Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 15 (4): 421–447.

- Stockhammer, E., and R. Stehrer. 2011. ‘Goodwin or Kalecki in Demand? Functional Income Distribution and Aggregate Demand in the Short Run.’ Review of Radical Political Economics 43 (4): 506–522.

- Stockhammer, E., Ö Onaran, and S. Ederer. 2009. ‘Functional Income Distribution and Aggregate Demand in the Euro Area.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 33 (1): 39–159.

- Stockhammer, E., J. Rabinovich, and N. Reddy. 2018. ‘Distribution, Wealth and Demand Regimes in Historical Perspective.’ FMM Working Paper 14-2018. Berlin: Macroeconomic Policy Institute.

- Storm, S., and C. W. M. Naastepad. 2012. Macroeconomics Beyond the NAIRU. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Storm, S., and C. W. M. Naastepad. 2013. ‘Wage-Led or Profit-Led Supply: Wages, Productivity and Investment.’ In Wage-Led Growth: An Equitable Strategy for Economic Recovery, edited by M. Lavoie and E. Stockhammer. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Temin, P. 1990. ‘Socialism and Wages in the Recovery from the Great Depression in the United States and Germany.’ Journal of Economic History 50 (2): 297–307.

- Waldenström, D. 2014. ‘Swedish Stock and Bond Returns, 1856–2012.’ In Historical Monetary and Financial Statistics for Sweden, Volume II: House Prices, Stock Returns, National Accounts, and the Riksbank Balance Sheet, 1620–2012, edited by R. Edvinsson, T. Jacobson, and D. Waldenström. Stockholm: Ekerlids förlag.

- Van Zanden, J. L. 2000. ‘Post-War European Economic Development as an Out of Equilibrium Growth Path: The Case of the Netherlands.’ De Economist 148: 539–555.

- Vartiainen, J. 1998. ‘Understanding Swedish Social Democracy: Victims of Success?’ Oxford Review of Economic Policy 14 (1): 19–39.