ABSTRACT

Is banking in the European Union still too-big-to-fail (TBTF)? We address this question by providing a critical overview of post-crisis banking regulation and examining whether financial markets continue to expect European governments to bailout TBTF banks. To the latter end we use a novel set of primary data, gathered from fieldwork in Europe, analyse credit ratings of TBTF banks, and compare them with the ratings of other European banks. Our results suggest that the expectation of government support for European banks is still present. Most notably, TBTF banks command a long-term credit rating about three notches higher than what would be the case in the absence of the expectation of government support. Other European banks enjoy significant rating uplifts too, albeit smaller in size.

1. Introduction

More than a decade since the US and Eurozone crises of 2008 and 2010, it remains an open question whether the systemic risks due to banks deemed as too-big-to-fail (TBTF) have been adequately addressed. While the issue of too-big-to-fail banking is far from new, the two crises brought it into the fore, largely due to the vast resources dedicated to rescuing failing banks on the two sides of the Atlantic.

There are a number of concerns associated with too-big-to-fail banking. Most commonly, authors point out the issue of moral hazard (e.g., Stern and Feldman Citation2004). Knowing they will be rescued by the government if necessary, TBTF banks have an incentive to adopt a riskier business model than they would otherwise. Secondly, the expectation of government support enhances the market value of TBTF banks and reduces their borrowing costs, thereby providing them with an implicit government subsidy and a competitive advantage vis-à-vis other banks (O’ Hara and Shaw Citation1990; Noss and Sowerbutts Citation2012; Brewer and Jagtiani Citation2013). Furthermore, TBTF banks hold vast political power and thus a strong ability to influence bank regulation (Taibbi Citation2012; Ioannou, Wójcik, and Dymski Citation2019; Urban et al. Citation2022). In Europe, the financial lobby, led by TBTF banks, has been recorded to spend more than 100 million Euros annually, while also populating the advisory boards and committees of the European Central Bank and the European Commission with hundreds of representatives (Corporate European Observatory Citation2014; Citation2017). Their vast political power has also led authors to describe these banks as too-big-to-prosecute, in addition to being too-big-to-fail (Marshall and Rochon Citation2019). Global TBTF banks were also at the epicentre of the crisis of 2008, playing a leading role in the propagation of subprime lending, shadow banking and securitisation (FCIC Citation2011).

TBTF banking is not only about banks’ asset size, but also about expectations as to what would happen was a bank let to go bust, following an event of financial distress. Given the centrality of expectations, and thus the impossibility of providing a definite answer in advance, the issue largely comes down to the credibility attached to the ex-ante announcements of bank regulators and policy makers.

Typically, regulators and policy makers tend to firmly promise not to bail out TBTF banks. Nonetheless, there is nothing that guarantees they will stand by their word when faced with financial turbulence. Paul Volcker, Chair of the US Fed during the 1980s and a prominent regulatory advisor during the Obama administration, points out that ‘[f]aced with the clear and present danger of a severe fallout from a large bank failure, on the one hand, against the more amorphous and certainly more distant risk of losing market discipline, on the other hand, official judgments may be biased toward the “not on my watch” syndrome’ (Volcker Citation2004). Alessandri and Haldane (Citation2009) suggest a ‘doom loop’, wherein any ex-post failure of regulators to keep up with their promise not to bail out TBTF banks undermines their credibility, therefore allowing TBTF banks to grow bigger and riskier; in turn making it even more difficult for authorities to stick to their guns, thus perpetuating their declining credibility and so on.

While the topic of too-big-to-fail banking has American roots (FDIC Citation1997; Dymski Citation2011), analysis in the context of the European Union (EU) is also highly topical. First, the EU is itself the host to eight banks characterised as global-systemically important (G-SIB) by the Financial Stability Board, making it the second largest host after the United States (FSB Citation2022).Footnote1 Secondly, it is an area still rigged with unresolved economic tensions, related to its framework for economic policy, the co-existence of fiscal fragmentation with monetary integration (for countries of the Eurozone), and the standstill in the development of the European Banking Union.

Our contribution employs mixed methods. On the qualitative side, we start with a document analysis aiming to assess the most important bank reforms discussed in the EU since the 2010 crisis, separating between ideas that materialised into legislation and ideas that were abandoned. Following, we offer a novel set of primary evidence based on semi-structured interviews with high-profile professionals from finance and advanced business services in Europe, and high-level officials from the European regulatory agencies (all interviews were conducted in spring 2021, online due to the pandemic). On the quantitative side, we examine financial data on asset size, capitalisation ratios and credit-risk exposures of European TBTF banks. Further, we analyse bank credit ratings (shortly bank ratings), based on a sample of 67 European banks and the ratings of Moody’s, for the period 2011–22. Our overall approach in using mixed methods follows Jick’s (Citation1979) recommendation of treating quantitative and qualitative methods as complementary, with a view to learn something distinct from each.

Our evidence suggests that the conundrum of TBTF banking still remains unresolved in Europe, despite progress in banking regulation. Out of our fieldwork evidence, the majority of our interviewees still expect — or at least do not exclude — the possibility of government bailout support for TBTF banks. Even more, rather than being seen as a stigma, TBTF status is still appealing in many cases. At one extreme, an interviewee of ours from a European G-SIB compared their status with participation in the Champions League (INT_14). Next to this, our analysis of bank ratings provides evidence of a persistent rating uplift for European TBTF banks. Currently, the difference between the average ‘stand-alone’ rating (i.e., the evaluation of a bank’s creditworthiness based on its own financial condition) and the average long-term credit rating of European TBTF banks amounts to three rating notches. Other banks in our sample enjoy significant rating uplifts too, albeit smaller in size.

Our paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, we discuss TBTF banking in the context of the EU. Following, we elaborate our qualitative and quantitative methodologies. This is followed by a detailed discussion of all our findings. In the last section we conclude and reflect on policy.

2. Too-Big-to-Fail Banking in the European Union

To understand TBTF banking in the European context, it is important to start by considering the broader economic characteristics of the area. To begin with, while the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 and the European Stability and Growth Pact (ESGP) of 1997 set common targets for fiscal policy at the pan-European level, the implementation of fiscal policy has always been left to national governments. In addition, the fiscal space of member countries is significantly bounded by the legal limits set for fiscal deficits and public debt, 3 per cent and 60 per cent respectively.Footnote2 This tension is even more acute for countries of the Eurozone, given their common currency and, consequently, their lack of monetary autonomy (Wray Citation2003; Papadimitriou, Wray, and Nersisyan Citation2010; De Grauwe Citation2011).

Next to the frameworks for fiscal and monetary policy, there are the tensions related to the EU’s Banking Union. Notably, despite the fact that the EU has moved towards a common banking regulation and supervision, deposit guarantee schemes are still to this date a matter of national policy (European Commission Citation2022a). As currently listed in Commission’s website, the most recent official communication on the Banking Union dates back to 2017 (European Commission Citation2022a).

Part and parcel of the incompleteness of the Banking Union is the fact that national governments in the EU had to step in and commit vast resources for supporting their banking systems during the US and Eurozone crises, despite their narrow fiscal space. According to the calculations of Stolz and Wedow (Citation2010), 167 billion Euros were provided to banks by national governments as capital injections between 2008 and 2010. A further 569 billion Euros were committed for guaranteeing purchasing of bonds and about 129 billion Euros for removing precarious assets from banks’ balance sheets.Footnote3 Put into perspective, the total commitment for bank support during this period amounted to about 25 per cent of the GDP of the EU for 2008 (2010).

Despite the above, financial markets’ original reaction to the rise of fiscal spending was relatively mild. In part, this can be explained by the fact that the European countries most exposed to the US crisis (France, Germany, Spain, Netherlands and Ireland) all enjoyed triple-A ratings by 2008. Furthermore, save for Ireland whose sovereign rating (by Moody’s) fell by seven notches between 2008 and 2010, from Aaa to Baa1, the ratings of other countries remained stable. By the end of 2010, the sovereign ratings of Germany, Netherlands, and France were still at the triple-A category (and are still there Germany and the Netherlands), while Spain’s rating was down just by one notch, from Aaa to Aa1 (source: Moody’s).

This changed in 2010 when the Eurozone crisis broke out. Faced with the exhaustion of their own fiscal space and their lack of monetary autonomy, peripheral European economies, such as Greece, Spain and Ireland, got trapped in a vicious circle in which sovereign stress and banking stress closely interacted with each other, generating a self-reinforcing loop, with increases in sovereign interest rates fuelling banking instability, in turn boosting further sovereign interest rates, and so on (Acharya, Drechsler, and Schnabl Citation2014; Gibson, Hall, and Tavlas Citation2017). To avoid the implosion of their domestic banks, these countries had to request external bailout support, a support that was provided by what came to be known as the ‘Troika’ (European Commission, European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund), on the condition of privatisation and austerity reforms.

Banks of core European countries benefited substantially from the bailout packages designed for countries of the European periphery, particularly Greece. Bortz (Citation2019) calculates that out of the funds loaned to Greece between 2010 and 2014 (216 billion Euros in total), 77 per cent were used for supporting the country’s original creditors, the majority of who were foreign lenders, particularly French and German banks (IMF Citation2010).Footnote4 In his recent political memoir, Barack Obama corroborates this observation, writing that when Greece’s first bailout was negotiated, Nicolas Sarkozy and Angela Merkel (French and German leaders at the time) ‘ … rarely mentioned that German and French banks were some of Greece’s biggest lenders [… a fact] that might have made clear to voters why saving the Greeks from default amounted to saving their own banks … ’ (Obama Citation2020, p. 531).

Indeed, a unique feature of European TBTF banks, relevant to explaining the eagerness of German and French officials to support their banks, is the narrative of national banking ‘champions’. From this point of view, large European banks are necessary to compete with the US banking giants, which would otherwise take over parts of their business. During the years of the European crisis, German and French officials such as Christian Noyer and Pierre Moscovici were quite open in admitting their fear that a tough regulatory framework for their banks would have been a ‘gift’ to the US (Hardie and Macartney Citation2016).Footnote5

Currently, the EU is host to eight banks identified as G-SIB by the Financial Stability Board (FSB Citation2022). These include BNP Paribas, BPCE, Crédit Agricole, Société General, Banco Santander, Deutsche Bank, UniCredit and ING. The first four are headquartered in France, while the rest are headquartered in Spain, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, respectively. Spain’s BBVA and Finland’s Nordea Bank were also listed as G-SIBs temporarily, the first from 2012 to 2014, and the second from 2011 to 2017 (FSB Citation2011; Citation2012).

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Qualitative Analysis

Our qualitative analysis separates into two parts. First, we conduct a document analysis, focusing on European policy and consultation reports (Section four). Our aim is, first, to take stock of the most significant bank reforms implemented in the EU since the 2010 crisis, and second, to delve into the debates of the time about how to re-regulate the European banking sector. Our discussion encompasses not just those ideas that turned into actual policy reforms, but also the ideas for reform that were discussed but ultimately abandoned. We scrutinise several webpages and official documents of the European Commission and other EU and international institutions, reflect on the ideas put forward in the Liikanen report, and incorporate insights from previous literature on the topic (e.g., Hardie and Macartney; Quaglia and Spendzharova Citation2017).

Second, we provide a novel set of evidence, based on twenty-two interviews with high-profile professionals from finance and advanced business services in Europe, as well as high-level officials from regulatory agencies (Section five). All interviews were conducted between March and April 2021, online due to the pandemic, as part of a larger fieldwork campaign on financial centres in Europe. Nine of our interviews were with professionals from European G-SIBs, four with professionals from the accounting and consulting sector, and six with professionals from national and multi-national authorities, including central banks. We also interviewed a professional from a FinTech company, one from a professional banking association, and one from an international investment bank (Appendix B). In all cases, our interviews lasted about an hour and were recorded and transcribed.

All our interviews were semi-structured (Clark Citation1998; Longhurst Citation2010). This approach allowed interview partners to drive the conversation, whenever we deemed this was beneficial to our research. This strategy was particularly valuable as it allowed each interviewee to spend more time on issues they were most familiar with and considered most important. For arranging interviews, we used our own networks, as well as corporate websites and LinkedIn. When using our networks, we applied the snowballing technique of asking contacts for further introductions. Our target in terms of seniority of interviewees was the executive level, whenever possible. The names of interviewees, details of their organisations, and precise locations of interviews have been anonymised.

3.2. Quantitative Analysis

Our quantitative analysis starts with an examination of selected balance sheet data of European G-SIBs. We investigate, in particular, the changes in the asset size of G-SIBs since the 2010 crisis, as well as the changes in their capitalisation ratios. Furthermore, we track the cross-border credit risk exposures of selected G-SIBs, contrasting them with the five largest European banks that were never part of FSB’s list. Our approach is consistent with the observation that TBTF banking is not just a matter of size, but also of interconnectedness with the broader banking system.

Following, we provide a quantitative analysis of bank ratings, based on a sample of 67 European banks and the ratings of Moody’s, one of the world’s biggest credit rating agencies (CRAs). For our purposes, we treat bank ratings as a proxy for financial markets’ expectations, on the basis of the documented influence that CRAs exercise on investors (Sinclair Citation2005; Ioannou Citation2021). A major advantage of the analysis of credit ratings, as compared to fieldwork research, is the ability to examine not just the recent state of market expectations, but also the evolution of these expectations since the Eurozone crisis.

Moody’s calculates and publishes two different credit ratings for each bank it rates (Moody’s Citation2021). One is the bank’s stand-alone rating, which reflects a bank’s own financial status and performance, and is informed by the broader macroeconomic profile of the country where the bank operates, the financial profile of the bank itself (e.g., funding structure, profitability, asset risk, etc.), and any qualitative factors related to the bank’s operations and strategic orientation. This rating also incorporates Moody’s expectation of any internal support the bank might be able to receive from its parent company or some other affiliate in the event of distress. Following, Moody’s publishes its overall long-term rating of the bank. This is set equal to the bank’s stand-alone rating, plus a rating uplift according to Moody’s expectation of government support in the event of financial distress. According to the agency, three major factors that inform its expectation of government support are the size of the bank, its interconnectedness with the rest of the financial system, and the capacity of the corresponding government to provide such support (Moody’s Citation2021, p. 88–91).

Our approach builds on previous empirical research that uses the difference between the two types of ratings as a proxy for identifying financial markets’ expectation of government support to TBTF banks (Noss and Sowerbutts Citation2012; Ueda and di Mauro Citation2013; Davies and Tracey Citation2014; IMF Citation2014; Toader Citation2015; Schich and Toader Citation2017). As highlighted by these authors, a rating uplift due to the expectation of government support practically amounts to lower borrowing costs, and correspondingly, to an implicit government subsidy. Such subsidy gives a competitive advantage to TBTF banks, enhances returns for their shareholders, encourages risk taking, and enables TBTF banks to grow even bigger. Davies and Tracey (Citation2014), of the Bank of England, show that once implicit government subsidies are considered, the supposed economies of scale of TBTF banks evaporate.

A possible alternative for measuring the expectation of government support is by considering banks’ actual borrowing costs. While this approach has the potential of estimating the size of implicit government subsidies more directly, as compared to bank ratings, it has several drawbacks (Noss and Sowerbutts, Citation2012; Schich Citation2018). First, interpretation is less clear. Whereas CRAs provide an explicit description how they measure their expectation of government support, the use of borrowing costs strongly depends on counterfactual scenarios as to what would these be in the absence of the expectation of such support. Secondly, fluctuations in market conditions can easily distort findings. In an environment of ultra-low interest rates, for example, actual savings in borrowing costs for TBTF banks are likely to turn out to be very small or inexistent, regardless of any expectation of support by governments.

Our analysis covers the period 2011–22. For our purposes, we convert Moody’s alphanumerical ratings into a numerical format and examine the simple difference between stand-alone ratings and long-term ratings. Our conversion is linear, in other words numerical and alphanumerical differences are equal at any point across the rating scale (Appendix A). Our selection of banks is based on the banks listed in the transparency exercise page of the European Banking Authority (EBA), filtered according to the coverage of Moody’s. EBA’s list of banks includes those identified as G-SIB, as well as the largest banks in each EU member state. Greece’s four biggest banks, for example, are included in the sample, despite none of them being global-systemically important. We provide the detailed list of banks in Appendix C, with those identified as G-SIB by the Financial Stability Board stated in bold (FSB Citation2022). Although Spain’s BBVA and Finland’s Nordea Bank are not currently listed as a G-SIBs we also flag them as such given that they have been identified as such by the FSB in previous years. This gives us a total of ten European G-SIBs. Out of these banks, ING is the only one without historical ratings data from Moody’s. Our data on credit ratings go up to August 2022.

4. Post-crisis Reforms in European Banking

4.1. Capital Requirements and Resolution Directives

Two major steps taken by the EU in the direction of re-regulating European banking after the 2010 crisis were the increase in capital requirements and the establishment of a resolution mechanism for failed banks; the first in 2013 with the introduction of the Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV), and the second in 2014 with the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD).

The Capital Requirements Directive IV was the implementation of the corresponding part of Basel III in Europe. For banks classified as G-SIBs the increase in capital requirements was complemented by a further rise, based on the recommendations and classification of the Financial Stability Board (FSB). Depending on their precise positioning in FBS’s annual ranking, European G-SIBs are required to hold an additional capital buffer between 1 per cent and 2.5 per cent of their risk-weighted assets (FSB Citation2022). Indicatively, BNP Paribas, which for 2022 was listed as the seventh most systemically important bank globally, is required to hold an extra 1.5 per cent. At the lower end, UniCredit and Santander are required to hold an additional 1 per cent.

EU’s Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive were meant to be Europe’s flagship reform to put an end to the too-big-to-fail problem. Under the Directive, a bail-in mechanism was put in place, in which shareholders and creditors take priority in rescuing a failing bank, followed by support from a resolution fund, built on advance contributions by banks. Applicability of the Directive was set at the national level. For the countries of the Eurozone, implementation went a step further with the transferring of power and competency to the supranational level and the creation of the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) — one of the main pillars of the European Banking Union. The Single Resolution Board (SRB) and Single Resolution Fund (SRF) are the two main institutions that fall under the umbrella of the SRM.

There are several important points to highlight with regards to BRRD. First, the resolution legislation is still a roadmap, largely untested in practice. Only two cases of implemented resolution are mentioned in the official website of the European Commission. One is the resolution of the Slovenian and Croatian subsidiaries of the Russian Sberbank in March 2022, closely related to the war in Ukraine and the international economic sanctions on Russia (European Commission Citation2022b). The other is the resolution of Banco Popular Español in 2017 (European Commission Citation2022b), which was subsequently bought by Santander. Secondly, as legislated the BRRD still leaves open space for bailout with public money, now called ‘precautionary recapitalisation’. The support of the Italian bank Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS) in 2017 is an example of government bailout compatible with the BRRD (European Commission Citation2017a; Quaglia and Spendzharova Citation2017). Third, the build-up of the Single Resolution Fund is still ongoing, with its completion targeted for the end of 2023 (SRB Citation2022). As of July 2022, the Fund held a total stock of EUR 66 billion (SRB Citation2022), a figure representing about 0.5 per cent of the combined asset size of the ten European G-SIBs alone (13.71 trillion Euros in 2021).

4.2. Stress Tests and Transparency Exercises

Another step taken by the European Union was the introduction of stress tests for banks operating in the area. EU-wide stress tests are co-ordinated by the European Banking Authority (EBA) and are conducted on a bi-annual basis. To be invited for a stress test a bank needs to have a minimum of EUR 30 billion in consolidated assets, a threshold that covers 70 per cent of the European banking sector (EBA Citation2021). The main idea behind stress tests is to test banks’ resilience in dealing with hypothetical adverse scenarios such as a prolonged recession. EBA’s stress test for 2021, for example, considered the adverse scenario of prolonged effects of the covid-19 pandemic (EBA Citation2021). The European Central Bank (ECB) also carries out similar tests on an annual basis for the banks it supervises (ECB Citation2022).

Besides stress tests, another post-crisis mandate of the EBA is to conduct annual transparency exercises for the biggest banks of each EU member state. The aim is to closely monitor and disclose banks’ balance sheet data, with a detailed break-down at the level of sectoral and cross-country exposures of each bank (EBA Citation2022).

4.3. The Liikanen Report and European Commission’s Proposal on the Prohibiting Proprietary Trading

While the consultation of the above reforms was under way, back in 2012, the proposal on the structural reform of the EU banking sector, the so-called Liikanen report, came out, commissioned by the European Commission. The main call of the proposal was to internally separate (ring-fence) proprietary trading and other high-risk activities (e.g., derivative positions taken in market-making) from retail banking. Specifically, it recommended separation if risky activities were to amount to a significant share of a bank’s business, estimated at the time at 15–25 per cent of total bank’s assets, or 100 billion Euros in absolute terms (Liikanen, Bazinger, and Campa Citation2012, p. v).

As discussed in Hardie and Macartney (Citation2016) and Quaglia and Spendzharova (Citation2017), although the European Commission was at the time receptive to the recommendations of the report and keen on the idea of even more radical steps, a number of EU countries chose to legislate pre-emptively, establishing milder reforms at the national level. France and Germany were the two most important countries to do so. Both legislated banking reform bills in 2013, with the supposed aim to promote safe banking, though in both cases the legislated reforms were lighter versions of the recommendations of the Liikanen report to ring-fence big banks. In France, for example, only those proprietary trading activities that were deemed as ‘speculative’ were forced to be separated from retail banking.

There were two lines of logic that were employed by French and German authorities for justifying pre-emptive legislation. One was the idea that the prohibition of trading activities should not compromise banks’ ability to serve the real economy. Despite this rhetoric, however, neither France nor Germany tried to make the argument more explicit as to which activities were supposed to have positive effects on lending (Hardie and Macartney Citation2016). The second was the need to protect their national banking ‘champions’, primarily against Wall Street (Hardie and Macartney Citation2016).

Following national reforms, the European Commission published its own official legislative proposal in January 2014. Besides endorsing the Liikanen report, the proposal also recommended the prohibition of proprietary trading for big banks (European Commission Citation2014, p. 26). Despite its delay, it was meant to be Europe’s response to the Dodd-Frank Act of the US. The proposal was met with opposition from the Council of the EU, which in the summer of 2015 presented its own draft for structural reform (Council Citation2015). The draft did not mention the prohibition of proprietary trading at all. Instead it suggested a light version of ring-fencing, which member states could implement at the national level, as had already happened in countries like France and Germany. The chasm in legislative proposals between the Commission, the Council and the European Parliament was not bridged in the years that followed, so that none of these ever found their way into becoming European law. Ultimately, in the autumn of 2017 the Commission announced its intention to withdraw its 2014 proposal (European Commission Citation2017b) and officially abandoned it in the summer of 2018. To justify its decision, it pointed out the lack of progress and the absence of any foreseeable agreement (European Commission Citation2017b). It also asserted, in a rather laconic manner, that the purpose of the proposal had largely been achieved already by the rest of the European reforms on banking supervision and resolution (European Commission Citation2017b). Despite this statement, no elaboration of how these reforms had satisfied the need for structural reform was offered anywhere.

5. Professional Perceptions of TBTF Banking in Europe

The broad themes that emerged in our interviews concerned our interview partners’ attitude towards post-crisis reforms in Europe, their expectations of future government bailouts of TBTF banks, and whether they believe G-SIBs prefer to be identified as such. According to our findings, there seems to be an almost unanimous agreement on the adequacy of post-crisis bank reforms. Nonetheless, our interviewees still expect, or at least do not exclude, the possibility of government bailouts for G-SIB and other TBTF banks. Furthermore, we recorded mixed responses on the question whether G-SIBs prefer to be classified as such.

To support the claim on the adequacy of post-crisis reforms several interviewees brought up the example of the pandemic. INT_19, for example, argued that this time banks were more part of the solution than anything else. The only critique that was almost unanimously voiced by our interviewees was about the incompleteness of the Banking Union, particularly the absence of a pan-European deposit guarantee scheme (e.g., INT_11, INT_15). Beyond that, only one of our interviewees, from a lead national authority in the UK, described the aftermath of the global financial crisis as a missed opportunity for financial re-regulation (INT_6). From his/ her point of view, the undertaken reforms did indeed increase banking resilience in a fairly basic sense but did not change the system fundamentally. One step in this direction, according to our interviewee, would have been to move towards activity — rather than institution-based regulation. Indicative of the difference between the two approaches is also the testimony of an interview partner from a multinational bank (INT_8) who suggested that regulators’ attempt to rein in proprietary trading led to ‘a large exodus of people […] going from banks to run hedge funds, doing exactly the same job but under less regulatory scrutiny’.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, interview partners from large banks were the ones that raised most concerns about adverse implications of new reforms. Several complained about the need for more capital, the inefficiency side of ring-fencing in pushing banks to duplicate many of their functions, the increased bureaucracy to meet new regulatory requirements, and ultimately the adverse effect on banks’ profitability (e.g., INT_9, INT_10, INT_13, INT_16).

All interview participants that were asked if TBTF banks are still likely to be bailed out by governments in the scenario of financial distress acknowledged such possibility, or at least did not rule it out, despite their overall sense of satisfaction with post-crisis reforms (INT_2, INT_8, INT_9, INT_16, INT_17, INT_18, INT_20). The following response, from interview partner INT_9, from a European G-SIB, is indicative of this view:

Until you actually get bust, [resolution planning] translates in nothing else than paperwork. […] Nevertheless, to me, what’s important is […] the resolution fund that is gradually building up for the next big crisis.

.. I’m no longer worried about a large bank blowing up, because I believe that has been addressed, and I continue to believe that there will be government intervention for large banks. […] I see a difference between the rhetoric and the reality. The rhetoric is for the voters. […] You know, “We will not bail out banks, we will not … ” […] I am sure that, at some point in time, we will see a sizeable bank being resolved, in order to give a lesson that it happens. But this will never be […] the home of the savings of the majority of the people in the country.

… my bank made a conscious effort to […] move into Tier 3, to get out of Tier 2 and to get rid of some businesses and to only go into the investment banking businesses where we have a niche […] Tier 1 is only for the Americans […] no European banks can compete with the Americans, they have to understand that and figure out how they’ll redo their models and the ones that aren’t realising that are going to go out of business …

… [G-SIB status] has advantages and it has also some disadvantages. The advantage is that we are […] supervised directly by the ECB. The problem is that [there are] a lot of LCAs, local competent authorities, who thing they can regulate us at the same time, so that doesn’t make it easier. But generally speaking, we are in a good group of banks. […] we tell ourselves that, if you are a global FC, you play Champions League football, but then in the super Champions League, where only the Spanish and Italians and the English get to play, then that comes at a price. And it also gives you a kind of status, […] If you are a Champions League football player, you […] have to do everything top, otherwise you will never win. You have to be 10 out of 10 in everything you do. And that realisation took a bit of time to get a grip on us, but that is actually an advantage. Because you make yourself a safer bank at the end of the day.

6. Quantitative Analysis

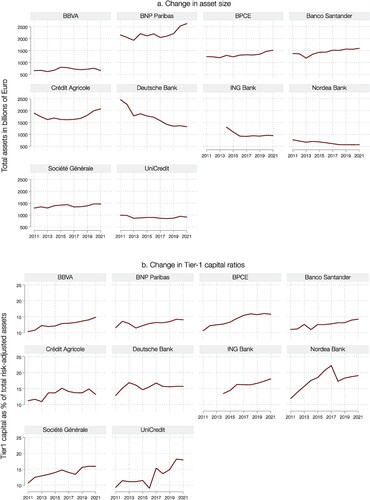

(a) shows that in most cases the asset size of European G-SIBs has either increased or remained stable since 2011. BNP Paribas’s asset size has increased from 2155 billion Euros in 2011 to 2634 billion Euros in 2021, making it the biggest European G-SIB nowadays (figures adjusted for inflation). BPCE, Santander, Credit Agricole and Société General have also grown. The most evident exception to this trend has been the decline of Deutsche Bank, with asset size in 2021 almost half of what it was in 2011. Next to this, (b) confirms the positive impact of enhanced capital requirements on the capital-asset ratios of European G-SIBs. Taken on average, the Tier-1 capital ratio of the ten banks displayed in the figure increased from 11.06 per cent in 2011 to 15.89 per cent in 2021.

Figure 1. Changes in asset size and Tier-1 capital ratios of European global systemically important banks (G-SIBs). Source: S&P Global and authors’ calculations.

Notes: list G-SIBs includes the ones listed as such by the Financial Stability Board (FSB Citation2022) as well as those that have been listed as such in the past (BBVA and Nordea Bank); asset size figures adjusted for inflation.

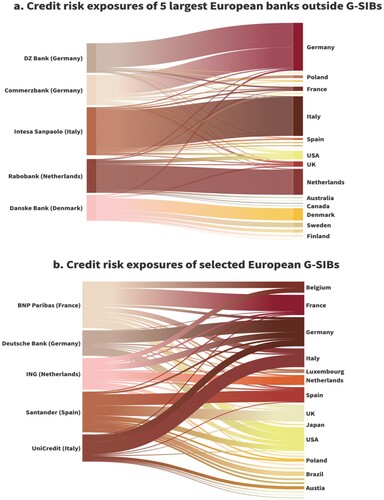

The lower part of ((b)) highlights the cross-border interconnectedness of some of the European G-SIBs, by displaying their total credit risk exposures as of June 2021. Seen in comparison with the upper part ((a)) which includes the five largest European banks that were never labelled as G-SIBs (size measured in terms of average asset size for the period 2011–21), the figure confirms the high cross-border diversification of European G-SIBs’ portfolios. Whereas most exposures of non-G-SIB big banks are within borders, the figure suggests a much ‘messier’ picture for G-SIBs. It also reveals that the exposures of European G-SIBs are mostly within Europe, save for their significant exposures to the USA and for Santander’s notable exposure to Latin America.

Figure 2. Credit risk exposures of selected European banks. Source: European Banking Authority, 2021 EU-wide Transparency Exercise (EBA Citation2022) and authors’ calculations. Elaboration in Flourish.

Notes: G-SIB for global systemically important banks. Countries of origin in brackets. Data corresponds to exposures as of June 2021.

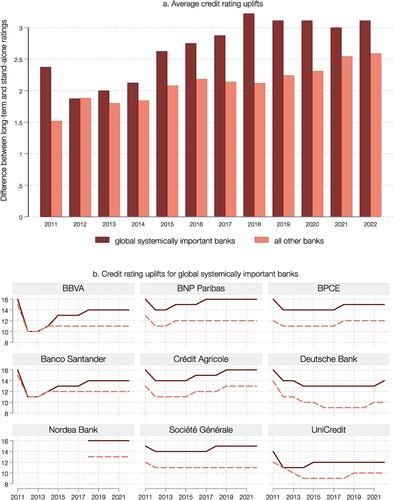

Coming to our analysis of bank ratings, (a) shows that rating uplifts — i.e., the difference between long-term and stand-alone ratings of banks — never went away, neither for G-SIBs nor for other banks included on EBA’s list. Currently, the average rating uplift for European G-SIBs amounts to about three notches.Footnote6 Save for a decline circa 2012, rating uplifts for G-SIBs followed an increasing trajectory for most of the 2010s, and remained stable during the covid-19 pandemic. Rating uplifts for other banks are generally smaller than those of G-SIBs but are still significant, about two and a half notches on average. The fact that rating uplifts are non-trivial for non-G-SIB banks is because EBA’s list includes the largest banks of each EU country, besides G-SIBs. This means that our sample largely includes banks that are systemically important at the national level. To stick to some of the big non-G-SIB banks included in (a), Italy’s Intensa Sanpaolo, for example, currently enjoys a rating uplift of 2 notches, from none in 2011 (source: S&P Global). Likewise, Denmark’s Danske Bank and Netherlands’s Rabobank currently enjoy a rating uplift of three and four notches respectively, both two notches higher compared to their 2011 values.

Figure 3. Average credit rating uplifts for European banks. Source: S&P Global and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Rating uplifts measured as the difference between long-term and stand-alone credit ratings. Ratings converted into numerical scores, e.g., Aaa = 19, Aa1 = 18, etc. Global systemically important banks as listed in FSB (Citation2022), plus BBVA (listed as G-SIB from 2012 to 2014) and Nordea Bank (listed as G-SIB from 2011 to 2017).

(b) displays in further detail the stand-alone and long-term credit ratings of European G-SIBs, tracking their development since 2011. An important finding that emerges from the figure is the impact of the 2010 crisis on the rating uplifts of the G-SIBs located in countries of the European south (BBVA, Santander and UniCredit). Indeed, a commonality between Spain’s BBVA and Santander, and Italy’s UniCredit, is the fact that in both countries sovereign ratings experienced steep declines during the first half of the 2010s. Spain’s sovereign rating, for example, went from Aa1 in 2010 down to Baa3 in 2012 (source: Moody’s), a development clearly reflected in the elimination of rating uplifts for BBVA and Santander during this period. While such elimination would otherwise be desirable from a policy perspective, here it is as if the crisis of 2010 offered the wrong solution to the problem of TBTF banking.

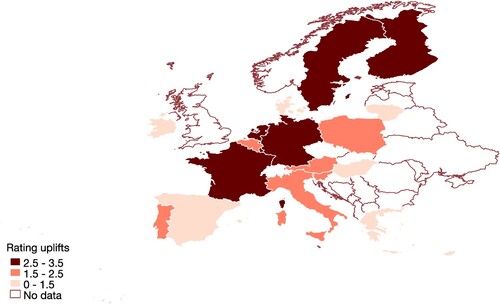

The influence of the fiscal power of national governments over banks’ rating uplifts, is further displayed in the map displayed in . In line with our previous observations, the map reveals a clear geographic unevenness in average rating uplifts by country, over the period 2011–22. Two patterns are worth emphasising. First, the de facto incompleteness of the European Banking Union. Although banking supervision and regulatory standards have moved towards the EU level, fiscal support for banking systems, whether in terms of deposit guarantee schemes, or expectations of bailouts, still remains a national matter. Secondly, the map confirms the penetration of the core–periphery dichotomy, commonly identified at the macroeconomic level (e.g., Bellofiore Citation2013; Lapavitsas et al. Citation2010; Palley Citation2013) into banking. At the core of the EU, Germany, the Netherlands and France, together with countries of Scandinavia, record the highest average rating uplifts for their banking systems. On the other side, countries of the European periphery, particularly Cyprus, Greece, Spain and Ireland record the lowest average bank rating uplifts.

Figure 4. Average credit rating uplifts for banks across the European Union, 2011–22. Source: S&P Global and authors’ calculations. The map only covers the countries of the European Union with banks in our sample. Source: S&P Global and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Rating uplifts measured as the difference between long-term and stand-alone credit ratings. Ratings converted into numerical scores, e.g., Aaa = 19, Aa1 = 18, etc.

7. Conclusion

In this paper, we take stock of the bank reforms implemented in the European Union since the 2010 crisis and assess their efficacy in containing the too-big-to-fail (TBTF) problem in Europe. There are a number of issues associated with too-big-to-fail banking, including moral hazard, implicit government support towards TBTF banks’ market value and borrowing costs, and excessive lobbying power. Being a threat rather than just a fact (Dymski Citation2011), TBTF status rests not just on the size of these banks, but also on the expectations of the market as to what would happen was a TBTF bank allowed to go bust. This puts regulators’ and policy makers’ commitments into the spotlight.

Following the US and Eurozone crises of 2008 and 2010, the European Union implemented a number of reforms to reduce the risks TBTF banks create for systemic stability and economic recovery. To this end, it increased capital requirements and introduced resolution planning, namely a roadmap how to resolve a systemic bank without committing taxpayers’ money. Nonetheless, the challenges associated with TBTF banking are still present. Other than the fact that most European global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) remain as big, if not bigger, financial markets still expect governments to step in and bailout out G-SIBs and other TBTF banks if needed. At one layer, this is confirmed by our own evidence from interviews with high-profile professionals from finance and advanced business services in Europe. At a further layer, it is corroborated by our analysis of bank credit ratings. Currently, G-SIBs in the EU enjoy a long-term rating about three notches higher to what it would be in the absence of any consideration of government support. Other European banks also enjoy significant rating uplifts, albeit smaller in size.

To deal with too-big-to-fail banking, particularly in the case of G-SIBs, investment banking needs to be fully separated from retail banking. Complete separation is crucial, not just for curtailing the volume and impact of opaque trade activities, and thus for facilitating financial stability, but also for containing the political power of big banks. Furthermore, it is a more solid reform, and thus one which has a greater chance of remaining in place in the medium run, once the lessons from the global and European financial crises start fading away.

To be sure, recent history shows that pure investment banks can still go back to being systemically important. This is the case of Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley in the US, to mention the two clearest examples. For this reason, the legal separation of investment from retail banking should be combined with limits in bank size. One idea how to make such limits operational could be by introducing steep hikes in corporate tax rates for banks exceeding a certain size. Amongst other aspects, such approach could also generate valuable tax revenue, which could be used for some broad cause outside banking, such as the tackling of climate change, or the support of people hit by earthquakes and other natural disasters.

A further policy option could be to use a large public bank as counterpart to TBTF banks (Marshall and Rochon Citation2019). Besides its potential to better serve the economy, such a bank could also remove part of the TBTF threat if able to quickly absorb a TBTF bank’s retail operations (Marshall and Rochon Citation2019). In the context of the EU, an idea along these lines could be to expand the mandate and operations of the European Investment Bank (EIB), by enabling it to take deposits and provide direct lending to small and medium-size enterprises, and by inserting it into TBTF banks’ resolution plans as the institution to take over their retail operations in the event of failure. Alternatively, a new European banking institution could be established to perform these functions, next to the EIB.

There are various ways in which our research can be expanded. A natural extension could be the re-consideration of the topic in light of the covid-19 pandemic, once data allows. Our own interviews took place while in spring 2021 while in lockdown, a time that was too-early to assess any medium- to long-term impacts of the pandemic. A further extension could be the investigation of the broader macroeconomic linkages of too-big-to-fail banking, particularly as related to sustainable growth and employment.

Ethics Statement

Central University Research Ethics Committee (CUREC), Oxford University, 4 April 2016.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of the paper were presented in the Workshop on the Current State of Finance in the EU: Prospects and alternatives, held at the Poulantzas Institute in Athens in March, 2019, and the Annual Meeting of the American Association of Geographers, held in Washington DC in April, 2019. We would like to thank Gary Dymski and Marica Frangakis for their valuable feedback. We are also grateful to the editor, Louis-Philippe Rochon, and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. We also want to thank Evangeline Burrowes and George Dietz for their precious assistance with the collection of the data. The paper has benefited from funding from the European Research Council (European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme; grant agreement no. 681337). The article reflects only the authors’ views and the European Research Council is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For this paper we consider the terms TBTF and G-SIB as synonymous.

2 Despite these de jure limits, member states have often violated them, most conspicuous example being the sky-rocketing of Ireland’s fiscal deficit in 2010 (32%). Since spring 2020, these thresholds have also been temporarily suspended due to the covid-19 pandemic and, following, the war in Ukraine, with suspension expected to last until the end of 2023 (Euronews Citation2022).

3 For consistency with the rest of this article we have deducted the sums corresponding to the UK, despite the UK being part of the EU at the time.

4 Support to Greece’s original creditors took a number of forms, including repayment of maturing debt, interest payments, debt buy-back and debt restructuring.

5 Christian Noyer was governor of the Bank of France in 2003–15; Pierre Moscovici was the minister of finance in France in 2012–14.

6 Actual ratings are discrete variables (Appendix A). The reason they appear as continuous in figure 3a is because we calculate them in average form.

7 For all banks we use mid-quotes for 5-year senior debt, using data from S&P Global (data is available for 45 of the 67 banks of our sample).

References

- Acharya, V., I. Drechsler, and P. Schnabl. 2014. ‘A Pyrrhic Victory? Bank Bailouts and Sovereign Credit Risk.’ The Journal of Finance 69 (6): 2689–2739.

- Alessandri, P., and A. Haldane. 2009. ‘Banking on the State.’ Paper Presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago 12th Annual Multinational Banking Conference on “The International Financial Crisis: Have the Rules of Finance Changed?” Chicago, September, 25.

- Bellofiore, R. 2013. ‘‘Two or Three Things I Know about her’: Europe in the Global Crisis and Heterodox Economics.’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 37 (3): 497–512.

- Bortz, P. 2019. ‘The Destiny of the First Two Greek “Rescue” Packages: A Survey.’ International Journal of Political Economy 48 (1): 76–99.

- Brewer, E., and J. Jagtiani. 2013. ‘How Much Did Banks Pay to Become Too-Big-To-Fail and to Become Systemically Important?’ Journal of Financial Services Research 43 (1): 1–35.

- Clark, G. 1998. ‘Stylized Facts and Close Dialogue: Methodology in Economic Geography.’ Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88 (1): 73–87.

- Corporate European Observatory. 2014. ‘The Fire Power of the Financial Lobby. A Survey of the Size of the Financial Lobby at the EU Level.’ Published by the Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), The Austrian Federal Chamber of Labour and The Austrian Trade Union Federation. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/attachments/financial_lobby_report.pdf.

- Corporate European Observatory. 2017. ‘Open Door for Forces of Finance at the ECB: 500 financial lobbyists at large at the ECB - by invitation.’ Corporate European Observatory. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/attachments/open_door_for_forces_of_finance_report.pdf.

- Council of the European Union. 2015. ‘Council Position on Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and Of the Council on Structural Measures Improving the Resilience of EU Credit Institutions. 10150/15’, 19 June. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/24486/st10150-en15.pdf.

- Davies, R., and B. Tracey. 2014. ‘Too Big to Be Efficient? The Impact of Implicit Subsidies on Estimates of Scale Economies for Banks.’ Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 46 (1): 219–253.

- De Grauwe, P. 2011. ‘The Governance of a Fragile Eurozone.’ Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS), working Document no. 346. http://www.ceps.eu/book/governance-fragile-eurozone.

- Dymski, G. 2011. ‘Genie Out of the Bottle: The Evolution of Too-Big-To-Fail Policy and Banking Strategy in the US’, Post-Keynesian Study Group Working Paper. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.postkeynesian.net/downloads/soas12/Dymski-Banking-and-TBTF.pdf.

- Euronews. 2022. ‘EU Fiscal Rules will Remain Suspended to Cushion the Impact of Ukraine War.’ Euronews May 23. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/05/23/eu-fiscal-rules-will-remain-suspended-to-cushion-the-impact-of-ukraine-war.

- European Banking Authority (EBA). 2021. ‘2021 EU-Wide Stress Test.’ Methodological Note. 29 January. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.eba.europa.eu/sites/default/documents/files/document_library/Risk%20Analysis%20and%20Data/EU-wide%20Stress%20Testing/2021/Launch%20of%20the%20ST/962559/2021%20EU-wide%20stress%20test%20-%20Methodological%20Note.pdf.

- European Banking Authority (EBA). 2022. ‘2021 EU-Wide Transparency Exercise.’ Archive. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.eba.europa.eu/risk-analysis-and-data/eu-wide-transparency-exercise/2021.

- European Central Bank (ECB). 2022. ‘Stress Tests.’ Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/banking/tasks/stresstests/html/index.en.html.

- European Commission. 2014. ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of The Council on Structural Measures Improving the Resilience of EU Credit Institutions,’ 29 January, 2014/0020. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri = CELEX:52014PC0043&from = EN.

- European Commission. 2017a. ‘State Aid: Commission Authorises Precautionary Recapitalisation of Italian bank Monte dei Paschi di Siena.’ Press Release, 4 July. Accessed 14 February 2023. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-1905_en.htm.

- European Commission. 2017b. ‘2018 Commission Work Programme.’ An Agenda for a More United, Stronger And More Democratic Europe – Annex IV: Withdrawals,’ 24 October. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://commission.europa.eu/publications/2018-commission-work-programme-key-documents_en.

- European Commission. 2022a. ‘European Deposit Insurance Scheme: A Proposed Scheme to Protect Retail Deposits in the Banking Union.’ Accessed 14 February 2023. https://finance.ec.europa.eu/banking-and-banking-union/banking-union/european-deposit-insurance-scheme_en.

- European Commission. 2022b. ‘Bank Recovery and Resolution.’ Accessed 14 February 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/financial-supervision-and-risk-management/managing-risks-banks-and-financial-institutions/bank-recovery-and-resolution_en.

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). 1997. ‘History of the Eighties - Lessons for the Future’. Accessed 8 June 2023. https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/history/.

- Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC). 2011. ‘The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report.’ Accessed 8 June 2023. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-FCIC/pdf/GPO-FCIC.pdf.

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). 2011. ‘Policy Measures to Address Systemically Important Financial Institutions.’ Financial Stability Board, 4 November. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/Policy-Measures-to-Address-Systemically-Important-Financial-Institutions.pdf.

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). 2012. ‘Update of Group of Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs).’ Financial Stability Board, 1 November. Accessed 14 February 2023 https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/r_121031ac.pdf.

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). 2022. ‘2022 List of Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs).’ Financial Stability Board, 21 November. Accessed 24 November 2022. https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P211122.pdf.

- Gibson, H., S. Hall, and G. Tavlas. 2017. ‘Self-Fulfilling Dynamics: The Interactions of Sovereign Spreads, Sovereign Ratings and Bank Ratings During the Euro Financial Crisis.’ Journal of International Money and Finance 73 (B): 371–385.

- Hardie, I., and H. Macartney. 2016. ‘EU Ring-Fencing and the Defence of Too-Big-To-Fail Banks.’ West European Politics 39 (3): 503–525.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2010. ‘Greece: Staff Report on Request for Stand-By Arrangement.’ IMF Country Report No. 10/110. May 2010. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2010/cr10110.pdf.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2014. ‘Global Financial Stability Report. Moving from Liquidity- to Growth- Driven Markets. Chapter 3.’ Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2016/12/31/Moving-from-Liquidity-to-Growth-Driven-Markets.

- Ioannou, S., D. Wójcik, and G. Dymski. 2019. ‘Too-Big-To-Fail: Why Megabanks Have Not Become Smaller Since the Global Financial Crisis?’ Review of Political Economy 31 (3): 356–381.

- Ioannou, S. 2021. ‘Credit Rating Agencies in the Era of Neoliberal Capitalism.’ In In Routledge Handbook of Financial Geography, edited by J. Knox-Hayes and D. Wójcik. London: Routledge.

- Jick, T. 1979. ‘Mixing Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: Triangulation in Action.’ Administrative Science Quarterly 24 (4): 602–611.

- Lapavitsas, C., A. Kaltenbrunner, D. Lindo, J. Michell, J. P. Painceira, E. Pires, J. Powell, A. Stenfors, and N. Teles. 2010. ‘Eurozone Crisis: Beggar Thyself and thy Neighbour.’ Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 12 (4): 321–373.

- Liikanen, E., H. Bazinger, J. M. Campa, L. Gallois, M. Goyens, J. P. Krahnen, M. Mazzucchelli, et al. 2012. ‘High-level Expert Group on Reforming the Structure on the EU Banking Sector.’ European Commission Report, 2 October, Brussels.

- Longhurst, R. 2010. ‘Semi-Structured Interviews and Focus Groups.’ In In Key Methods in Geography, edited by N. Clifford, S. French, and V. Gill. London: SAGE.

- Marshall, C. W., and L.-P. Rochon. 2019. ‘Public Banking and Post-Keynesian Economic Theory.’ International Journal of Political Economy 48 (1): 60–75.

- Moody’s Investors Service. 2021. ‘Banks Methodology.’ July 9. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.moodys.com/researchdocumentcontentpage.aspx?docid = PBC_1269625.

- Noss, J., and R. Sowerbutts. 2012. ‘The Implicit Subsidy of Banks.’ Bank of England. Financial Stability Paper No. 15. May. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/financial-stability-paper/2012/the-implicit-subsidy-of-banks.pdf.

- Obama, B. 2020. A Promised Land. New York: Crown.

- O’ Hara, M., and W. Shaw. 1990. ‘Deposit Insurance and Wealth Effects: The Value of Being “Too Big to Fail”.’ The Journal of Finance 45 (5): 1587–1600.

- Papadimitriou, D., R. Wray, and Y. Nersisyan. 2010. ‘Endgame for the Euro? Without Major Restructuring, the Eurozone is Doomed.’ Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Public Policy Brief No. 113. Accessed 14 February 2023. http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/ppb_113.pdf.

- Palley, T. 2013. ‘Europe’s Crisis Without end: The Consequences of Neoliberalism.’ Contributions to Political Economy 32 (1): 29–50.

- Quaglia, L., and A. Spendzharova. 2017. ‘The Conundrum of Solving ‘Too Big to Fail’ in the European Union: Supranationalization at Different Speeds.’ JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (5): 1110–1126.

- Schich, S., and O. Toader. 2017. ‘To Be or Not to Be a G-SIB: Does It Matter?’ Journal of Financial Management, Markets and Institutions 2: 169–192.

- Schich, S. 2018. ‘Implicit Bank Debt Guarantees: Costs, Benefits and Risks.’ Journal of Economic Surveys 32 (5): 1257–1291.

- Sinclair, T. 2005. The New Masters of Capital: American Bond Rating Agencies and the Politics of Creditworthiness. London: Cornell University Press.

- Single Resolution Board (SRB). 2022. ‘What is the Single Resolution Fund?’ Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.srb.europa.eu/en/single-resolution-fund.

- Stern, G., and R. Feldman. 2004. Too Big to Fail: The Hazards of Bank Bailouts. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Stolz, S. M., and M. Wedow. 2010. ‘Extraordinary Measures in Extraordinary Times – Public Measures in Support of the Financial Sector in the EU and The United States.’ Discussion Paper Series 1: Economic Studies No 13/2010, Frankfurt-em-Main: Deutche Bundesbank. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/37071/1/631858768.pdf.

- Taibbi, M. 2012. ‘How Wall Street Killed Financial Reform.’ Rolling Stone, May 10. Accessed 14 February 2023. https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/how-wall-street-killed-financial-reform-190802/.

- Tsesmelidakis, Z., and R. C. Merton. 2012. ‘The Value of Implicit Guarantees.’ 26th Australasian Finance and Banking Conference 2013.

- Toader, O. 2015. ‘Quantifying and Explaining Implicit Public Guarantees for European Banks.’ International Review of Financial Analysis 41: 136–147.

- Ueda, K., and W. di Mauro. 2013. ‘Quantifying Structural Subsidy Values for Systemically Important Financial Institutions.’ Journal of Banking & Finance 37 (10): 3830–3842.

- Urban, M., V. Pažitka, S. Ioannou, and D. Wójcik. 2022. ‘The Financial Geography of Resilience: A Case Study of Goldman Sachs.’ Annals of the American Association of Geographers 112 (6): 1593–1613.

- Volcker, P. 2004. ‘Foreword.’ In Too Big to Fail: The Hazard of Bank Bailouts, edited by S. Gary and R. Feldman. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

- Wray, R. 2003. ‘Is Euroland Next Argentina?’ Centre for Full Employment and Price Stability, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Working Paper No. 23. Accessed 14 February 2023. http://www.cfeps.org/pubs/wp-pdf/WP23-Wray.pdf.

- Zhao, L. 2018. ‘Market-Based Estimates of Implicit Government Guarantees in European Financial Institutions.’ European Financial Management 24 (1): 79–112.

Appendices

Appendix A. Moody's scale for credit ratings of banking institutions.

Appendix B. List of interviews.

Appendix C. List of banks included in the analysis of credit ratings (global- systemically important banks in bold).

Appendix D. Borrowing costs for European banks

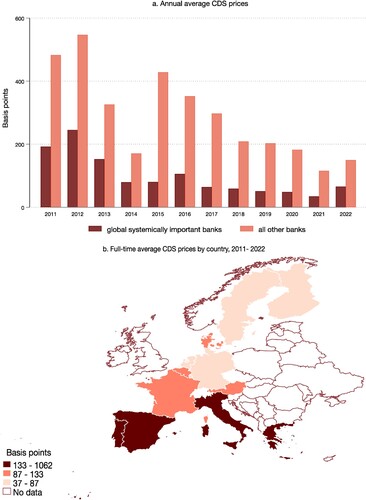

Here we provide a brief overview of borrowing costs for European banks, as supplementary material to our paper. For our analysis we consider the credit default swap (CDS) prices attached to the bonds issued by banks (Tsesmelidakis and Merton Citation2012; IMF Citation2014; Zhao Citation2018).Footnote7 While a thorough analysis to decompose CDS prices and isolate the component corresponding to the expectation of government support lies beyond the scope of our paper, our aim is to offer some indicative insights how borrowing costs differ by type of bank and by country.

(a) confirms that CDS prices are on average significantly lower for G-SIB than other banks. Save for the early 2010s, when they surpassed 200 basis points, they have also been significantly less volatile.

Figure A1. Credit default swap (CDS) prices for bonds issued by banking institutions in Europe. Source: S&P Global and authors’ calculations (data available for 45 of the 67 banks of our sample).

Notes: averages based on daily CDS prices for 5-year senior debt, mid-quotes.

Next to this, (b) illustrates the close relationship between CDS prices and the fiscal strength of national governments, for the period 2011–22. The figure is largely consistent with in highlighting the dichotomy between European core and periphery. Just as shows that rating uplifts due to the expectation of government support are the strongest for banks located in countries of the European core, (b) shows that these banks are also the most advantageously positioned for borrowing funds.