?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Suspense is a key narrative issue in terms of emotional gratification, influencing the way in which the audience experiences a story. Virtually all narrative media uses suspense as a strategy for reader engagement regardless of the technology or genre. Being such an important narrative component, computational creativity has tackled suspense in a number of automatic storytelling. These systems are mainly based on narrative theories, and in general lack a cognitive approach involving the study of empathy or emotional effect of the environment impact. With this idea in mind, this paper reports on a computational model of the influence of decorative elements on suspense. It has been developed as part of a more general proposal for plot generation based on cognitive aspects. In order to test and parameterise the model, an evaluation based on textual stories and an evaluation based on a 3D virtual environment was run. In both cases, results suggest a direct influence of emotional perception of decorative objects in the suspense of a scene.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, technology allows to create interactive or pseudo-interactive spaces of choice difficult to imagine just two decades ago. Not only there are new interfaces for innovative functionalities, but people have access to a practically infinite cosmos of potential multimedia experiences through which can choice what and how to start to consume, and when to stop it. Electronic books, films, serials, comics, music and web site written contents are within reach. If any choice is not good enough, other stimuli can be easily found.

In this context of endless offers, the audience has become more demanding. An example is the evident decrease of the consumption of horror and suspense literature and movies. Statistics about the number of tickets sold in horror films evidence this trend: the amount of sold tickets in 2014 was 63% lower than in 2006, following a negative trend since then.Footnote1 Thriller genre seems to do better, with only a drop of 44% from 2013 to 2014 (Nash Information Services, Citation2017). Therefore, the ratings of the most watched horror movies per year conveys another important and continuousFootnote2 descent of the assessment of the genre, from 71 points over 100 in 2006 (Saw III) to 39 last year (Annabelle) (Rotten Tomatoes, Citation2015).

Blaming Internet piracy is not possible, while these statistics are taken from 2006, when piracy was already an established practice. In fact, BSA Global Software Piracy Study reflects that Internet piracy rating globally decreased from 2006 to 2011, two points in North America and European Union (Bussiness Software Alliance, Citation2012). More decisively, copycat products, predictability, annoying, boring, lack of atmosphere and insipid characters (Spicer, Citation2012) affect the suspense and fear in a negative way. This seems to be leading to the apparently progressive decline of the most significant entertainment industry of suspense and fear during the last years (Billington, Citation2008), as happened with the horror literature in the 1990s (Hantke, Citation2008).

Moreover, this lowering is not observed in all the genres. For example, in comparison with horror and thriller genres, counting, respectively, 3 films each one among the 125 most popular movies from the last 5 years, science-fiction (20), superheroes (13), animation (13) and fantasy (8) can be usually found in the top positions of the ranking. Likewise, in the ranking of movie budgets, the categorised as pure thriller/suspense film firstly found is ranked 144th (Angels & Demons), descending to 420th when the first categorised mainly as horror film (Hannibal). In the opposite corner, the top 25 is mostly occupied by fantasy (10) and superheroes (9) movies.Footnote3

Even considering suspense no means limited to thrillers and horrors, and, thus, as part of nowadays any successful films, the most common source of suspense in movies is still the genre of thrillers and horrors. They naturally rely on intensive anxious feelings in order to maximally exploit their potential (Burget, Citation2014, pp. 39–40). Called by Krzywinska (Citation2002) “horror-based suspense” (p. 15), the integral ingredient of their narrative seems to require elements of forward-looking suspense to sustain audience interest (Salway & Graham, Citation2003, p. 302).

In this way and in order to justify the horror and thriller genres as the core-base of our study, we have to establish a difference between films with scenes of suspense and films which are based on suspense, due to there are some different usage (Vachiratamporn, Legaspi, Moriyama, Fukui, & Numao, Citation2015, p. 44). Several authors describe the relation between suspense, thriller and horror. For instance, as reported in the Toprac and Meguid's study (Citation2010), caution, terror and horror definitions resemble the definition of anxiety, suspense and fear, respectively. Experiment of Vachiratamporn et al. (Citation2015) suggests that stimulating player affect to the suspense state is the best way to maximise the effectiveness of producing a scary event (p. 50). Sparks et al. (Citation1993) pointed that frightening film is directly related to suspense (p. 465). Furthermore, Robinson, Callahan and Keith's experiment (Citation2014) results evidenced a strong relation between suspense and horror genre.Footnote4

This evidence that suspense is a key factor in a wide range of narrative media motivates the strong interest of computational creativity in the field (as detailed in Section 4). However, as discussed next, computational systems have focused on the narratological aspects of suspense, and they have mostly assumed the cognitive aspects that drive the perception of suspense in the audience. This is understandable given the deep complexity that analysing complex behaviour implies, and suspense, being affected by a probably high number of measurable aspects of general cognition, is no exception. To our best knowledge, there is no system focused on the atmosphere or decoration, but mainly rules, structure or description language.

Against the introduced background, the current research tries to advance towards a formalisation of suspense as a cognitive phenomenon. Working under the assumption that narratology can only provide an incomplete dimension of suspense, the main objective is to shed some light on the possibilities of the computational-cognitive modelling of such a complex phenomenon. Section 2 describes a general architecture meant to address the overall issues of this approach (Delatorre, Arfè, Gervás, & Palomo-Duarte, Citation2016a). Given that several narratological aspects of suspense focus on foreground features of the scene, it has been considered that the potential of this computational approach is higher in terms of its applicability due to the intention to provide coverage to a relatively unexplored component of suspense, and certainly one that is hardly capturable by narratology.

In particular, given the aforementioned challenge this implies, this paper describes a specific component of our proposal, namely the impact of the decoration and the context of suspenseful scenarios. Decorative elements are defined as those entities present in a scene or story which do not play a role in the main plot, and could therefore be interchanged by others or removed without any relevant change in the narrative structure of a story. In this context, a scene is a succession of information blocks that are provided to the audience. For this work, suspense is considered the emotion evoked by several features like uncertainty, outcome or empathy. A more detailed definition can be found in Section 3.

Against this background, this paper sets out to study the cognitive impact of decorative elements in suspenseful scenes, and provide a formal, predictive model ready to be applied in computational systems aiming to produce suspenseful narratives, which may be adapted to a number of different types of media. The model is based on the emotional impact of objects, extracted from the semantic study of terms in the ANEW study (Redondo, Fraga, Padrón, & Comesaña, Citation2007).

The main hypothesis guiding the study can be summarised as follows:

Decorative elements, even when not influencing the narrative plot, impact the perception of suspense. This impact is related to the emotional features of these objects.

In order to test the hypothesis and provide a formal model predicting the impact of decorative elements on suspense, a textual and 3D suspenseful scenes in which decorative elements change have been created. Human subjects experienced them, and they were queried about they suspense they perceived, and this reported suspense was compared against the ANEW values of the corresponding decorative elements.

If a correlation is found for sufficiently isolated changes, it would mean that decorative elements can influence suspense in a significative way, and that a formal approach based on semantic properties of these elements can help to predict the amount to which this happens. As show along the next sections, the analysis of the results certainly evidence the plausibility of the hypothesis, notwithstanding that we acknowledge this impact is complementary to other major aspects like plot.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 describes a overall computational model of creative production and the role of suspense in it, that frame this study. Section 3 details the working concept of suspense and the components assumed for the computational model, and Section 4 presents a review of several systems that model suspense as an element to generate stories. Later, Section 5 explains the evaluation against the human-based assessment of the models against textual stories and 3D environment. The results are presented in Section 6. The outcome of the evaluation was then used to train a regression model properly parameterised that predicts potential suspense of the decorative objects, which enables an algorithmic solution for adapting suspense based on it. This is detailed in Section 7. Discussion of the relative merits and limitations and general conclusions are provided in Sections 8 and 9, respectively.

2. General proposed model

As previously introduced, the presented model is meant to fill a gap in the computational systems addressing suspense by proposing a cognitive approach to suspense measuring and automatic adaptation. The model covers only a subset of features that affect suspense, namely the impact of decorative elements. As such, and in order to provide a general framework, this section offers an overall depiction of how the specific subset of the computational model of suspense (namely the effect of decorative elements on the perception of suspense) would relate to a more general model.

The main objective of the model proposed is the adaptation of the decorative elements in a scene, in such a way that the scene output is adjusted to the required suspense. This means that the global objective is to provide a system able to modify a scene by including, adapting or removing decorative elements in such a way that the suspense perceived by the audience is more adjusted to the input parameters.

Figure illustrates a simplified model of the theoretical modules composing the model. This architectural model consists in seven main elements (Scene, Intensity, Extractor, Components transformer, Corpus, Reassembler and Output scene) whose functions are described next.

2.1. Scene

The proposed model inherits the concept of Scene from cinematography. A scene is the unity of dramatic action which, endowed with initial approach, junction and outcome, is determined by a spacial location criteria and change at least one of the values of any character's lifeFootnote5 (Aranda & DeFelipe, Citation2006, p. 195; McKee & Lockhart, Citation2011, p. 56). For our purposes, we consider a scene as a succession of information blocks that are provided to the audience. Such information blocks will be divided in descriptions and actions. Descriptions are representations of characters or objects, relating or explaining their different parts, features or circumstances (Real Academia Española, Citation2001). These representations can be described by specific sentences or through the optional enrichment with adjectives of the part of the narrative where the elements are referred. Meanwhile, actions constitute a succession of events during the scene.

We illustrate a fragment of the original script of the shower scene of the film Psycho (Stefano, Citation1959) as example of these descriptions and actions:

Over the bar on which hangs the shower curtain, we can see the bathroom door, not entirely closed. For a moment we watch Mary as she washes and soaps herself.

There is still a small worry in her eyes, but generally she looks somewhat relieved.

Now we see the bathroom door being pushed slowly open.

The noise of the shower drowns out any sound. The door is then slowly and carefully closed.

And we see the shadow of a woman fall across the shower curtain. Mary's back is turned to the curtain. The white brightness of the bathroom is almost blinding.

Suddenly we see the hand reach up, grasp the shower curtain, rip it aside.

In this fragment, we can observe the descriptions (bar, curtain, semi-closed door, Mary, sightly worried eyes, noise, shadow of a woman, white brightness and hand) and the actions (Mary washes and soaps herself, door is pushed slowly open, door is slowly and carefully closed and the shower curtain is grasped and ripped).

We represent each of the elements as an information block in the same order that they are narrated, being descriptions or actions. In any case, in this paper we focus on descriptions, as being the items which our model operates with. For this modelling, we are analysing the description mode of some existent storytellings, searching for enough level of detail and robust knowledge representation. We put aside the process of actions for a future work.

2.2. Intensity

Intensity is represented as a quantitative integer value that indicates the desired level of suspense in the scene output. This way, if the difference between the required intensity and the intensity of the scene input is positive, the model will generate a more suspenseful scene, and vice versa. In case of coincidence, the scene output could involve a descriptive variation with respect to the scene input, but holding an equivalent suspense level.

As the intensity is an internal value whose range is not known by the user, we propose to specify the increment or decrement of the current intensity in the input. However, it is not necessary to include this option in the present model description, because the architecture is currently focuses on the functionality, not on the usability.

2.3. Extractor

The main process consists on three stages. In the first one, the extraction, description items have to be obtained from the information blocks. This step will depend on the scene input format: (a) if scene input contains the states of the plot including specify tags for identifying the suspense elements, the extraction is immediate; (b) if scene input is a narrative discourse, a more complex algorithm will be required for analysis, identification and classification. We are working on the first option, leaving the discourse for later.

2.4. Components transformer

As we have referred, an intrinsic part of the extraction system is the transformation of the concepts. This component selects elements of the plot considering the interesting elements: characters, environment descriptors, objects and facts. A second stage will select those elements implied in the plot according to their arousal and value of valence as measure of suspense affection.

After this, the goal of the transformation stage is to modify the descriptive elements, so the total amount of estimated suspense matches the intensity input. This implies the selection and launching of actions as Substitution, Insertion and Elimination (SIE) of characters features, characteristics of the environment and object's descriptions.

Transformation stage is complex: it implies making up a set of SIEs and select the most accurate in one way that the story keeps its consistency and the descriptor density deviation fits a minimum valid range. An evolutionary algorithm with customised heuristic of fitness is currently under production to satisfy our requirements.

2.5. Corpus

Our corpus consists on a set of terms, each one associated to a quantitative value that represents its level of suspense based on the already referred emotional valence, potential empathy and arousal. This information allows to measure the intensity of the scene from the previously extracted methods in the transformation stage.

In the current state of our research, we base the corpus information in three big groups: character features, objects and environments.

2.5.1. Character features

As the same way than corpus is weighted using emotional valence, potential empathy and arousal, character features are balanced. According to several definitions of suspense, in terms of the characters the emotion generated is related (although not only) to the fate of at least one of them (victim) due to the actions of another one (threat). Directly or indirectly, this figure and its features are the centre of what happens in a scene. According to Zillmann, the more dangerous and near is the threat, the more apprehension is experienced at the approach of the deplorable event. However, even this may seem obvious, we can not forget that the threat is not a static independent actor. On the contrary, the circumstances of the potential victim can change its nature.

For example, just before the mentioned Psycho's shower scene (Stefano, Citation1959), the film script describes Mary's circumstances:

She goes into the bathroom, drops the pieces into the toiler bowl, flushes the toilet. Then she drops her robe and steps into the tub and turns the shower on.

Over the bar on which hangs the shower curtain, we can see the bathroom door, not entirely closed. For a moment we watch Mary as she washes and soaps herself.

This way, the screenplay is preparing the viewer for amplifying the effect of the immediate scene of suspense through the victim's features, portraying her as a helpless person: she is nude, can not hear or see well due to the shower, and her ability to escape is obviously limited .Footnote6 On the contrary, if Mary had been warned, with the curtains open and a gun in her hands, suspense arousal would have been different comparing to the original script. Moreover, even if this is not the probable case, an extreme lack of sympathy for Mary could provoke that the spectator wouldn't really matter what will happen to her.

Summing up, a suspense generator must firstly take into account the character's features in the context of the threat, while the effect of its proximity in the viewer depends on the circumstances and characteristics of the victim that can be perceived and interpreted by the audience.

We propose three features to conform our corpus Character features block: (a) features related to balance of outcome-oriented implicit strengths; (b) features related to the empathy; and (c) features related to the proximity between threat and victim to the outcome, as a spatial or temporal dimension concerning both sides.

The first one refers to the perceptible ability of the victim to counteract the threat. It implies an extensive ontology of features that includes physical aspects such as size, physical strength, intelligence, perceptive skills or endurance; capabilities such as experience in the use of weapon or fantastic abilities as crossing through walls; and resources at hand such as armours, guns or flashlights. These features are measured and quantified for both victim and threat, and the difference between both values represents the influence of the strength in the suspense. Considering the revisions about the suspense, our hypothesis is that the stronger the threat is for the victim, the more potential suspense can be generated.

The second character feature is about empathy: the features that generates feelings of identification in the viewer. As explained in the previous section, just few features have been proved as empathisables. Concretely, race and attractivenessFootnote7 are two verified features that fit in the context of suspense. As well as the race can be easily represented by the model, the concept of “attractiveness” involves physical, mental, behavioural or derived from a position of power (including helplessness) which require a more complex treatment.

The last character feature refers to the proximity to the outcome. This is directly related to the scene tempo; as we have already mentioned, timing is an important criteria for evoking suspense. Therefore, suspense will increase as the threat is approaching the victim, physical (the killer) or just on timeFootnote8 (a countdown explosion). The behaviour of the victim and the threat are opposed: as the threat tries to reach the negative outcome, the victim struggles to get away from it. We consider that more suspense is inoculate in the audience the lower sum of the quantification of these distances is.

2.5.2. Objects

Objects involved in a suspense scene can take the role of: (a) elements which influences the scene plot; (b) decorative elements without direct participation. The model works on a different way depending on the case. As it depends on the context, this difference is not specified directly in the corpus.

The elements that influence the plot are related to the character strength, while they can take the role of resources that can help or harm to the character. For example, in Psycho's shower scene, the curtain can be consider an element that creates a disadvantage for Mary, as the knife brings improvement for the killer objective. It is different from the balance of strengths of the block Character features: our concept of character features implies implicit attributes or at hand resources, but the Object block refers to potential resources. The effect in suspense is different: at the moment that the killer is approaching, it is not the same for the audience viewing the victim having a gun that realising that there is a gun on a table at hand (available for the first to catch it). The preferred objective and the expected steps change, influencing the perception of the proximity to the undesired outcome: defense capability of the victim is lower if the victim can not reach the weapon. Our proposal is that suspense is effective if the plot is pushed to balance the original difference of strengths while the outcome is approaching. Thus, the elements in the scene can contribute to strengthen or to weaken any of its parts.

The other kind of object has only a decorative function. Even though the influence of the aesthetic in objects with an active role in the plot, there are many others that just “colour” the localisation. The valence of the elements influences its perception, which may have effect in suspense. For example, the toilet in Psycho's shower scene brings nothing to the events; moreover, it is not probably that the viewer can suppose any function related with the plot when the killer is approaching. However, Hitchcock decided to film it as he thought it would have emotional effects for the audience (Allen & Ishii-Gonzales, Citation2004, p. 269).

2.5.3. Environments

Being called spacial context, atmosphere or scenery, the environment is a verifiable generator of suspense. In the one hand, it affects to the skills of the characters. Meteorological effects like fog and rain reduce the perception; snow makes the floor tricky; ice slides. As part of day cycle, twilight and night has similar impact in visual abilities. It affects to the balance of strength, usually negatively for the victim. For example, in Psycho's shower scene, the bathroom was full of steam; even if Mary had been facing the door or without curtains, it should have been hard to recognise the silhouette and to be on guard.

On the other hand, even if there is no objective reasons to have any kind of valence for an specific environment, we can not discard the classical conditioning: we have learnt that focusing a long corridor in an old castle usually precedes a negative outcome, even if there are no grounds to think that the corridor in and old castle is worse than a corridor in a beautiful mansion. This behaviour is similar to the decoration elements.

2.6. Reassembler

The scene reassembler is the part of the model responsible for building a new scene based on the original, putting all together the block of the plot, in the format of the chosen storytelling, as the has been modified by the Transformer step.

In order to complete the process, the scene output is the result of the model. Again, we represent an example from the scene input of the original script of Psycho film's shower scene (Stefano, Citation1959), supposed a higher intensity required:

Over the bar on which hangs the shower curtain, we can see the bathroom door, not entirely closed. For a moment we watch Mary as she washes and soaps herself. Outside, we can hear a big storm in the middle of the night.

There is still a small worry in her eyes, but generally she looks somewhat relieved. She feels guilty and sad.

Now we see the bathroom door being pushed slowly open. A thunder resonates in the distance.

The noise of the shower drowns out any sound. The door is then slowly and carefully closed.

And we see the shadow of a woman crawling toward the shower curtain. Mary's back is turned to the curtain. The white brightness of the bathroom is almost blinding.

Suddenly we see the hand reach up, grasp the shower curtain, rip it aside.

There are differences between the scene input and the result. Firstly, an environment description has been included (the storm). Besides, it is reported that Mary feels guilty and repentant. Finally, the shadow is weirder that in the original version.

Computationally speaking, this theoretical framework relies on a robust system able to predict which of the candidate decorative elements is better suited in terms of the desired suspense. Having introduced the background in which the presented research is being developed, the rest of the paper explores a model to predict how suspenseful each decorative element is.

3. Related work on the impact of decorative elements, gender and emotions on suspense

Several authors define suspense as an emotion evoked by an strategical combination of a number of features as outcome (Carroll, Citation1984, p. 72), proximity (Lee & Hilinski-Rosick, Citation2012, p. 650), uncertainty (Burget, Citation2014, p. 44), empathy (Oliver & Sanders, Citation2004, p. 244) or sense of justice (Brewer, Citation1996, p. 114, 116). For instance, suspense is defined de Wied et al. (Citation1992) as “a high degree of certainty of a negative outcome” (de Wied et al., Citation1992, p. 325). Sternberg (Citation1978) affirms that suspense is sustained by the clash of intermittently aroused hopes and fears about the outcome of the future confrontation (Sternberg, Citation1978, p. 65). For Smuts (Citation2008) desire-frustration theory, suspense is created by the frustrated desirability about a character can escape from a undesirable destiny (Smuts, Citation2008, p. 289).

Additionally, environment influence on suspense is broadly support by suspense related literature (Delatorre et al., Citation2016b, p. 28). Concretely, Niedenthal (Citation2005) describes evocative lighting (as opposed to functional lighting), which allows the designer to manipulate the qualities of light (colour, shadow and lighting direction) to influence players' emotions (Niedenthal, Citation2005, p. 225) by the evocation of suspense, dread, comfort or ecstatic abandon (p. 229). vanVught & Schott (Citation2012) defends that atmosphere effects as dark/foggy and the music/soundscape are continuously suspenseful (vanVught & Schott, Citation2012, p. 100). Perron (Citation2012) sustains a similar opinion about the fog and darkness as used to hide what is not depicted: audience does not see very far, so is always scared to run into something awful (Perron, Citation2012, p. 27). According to Callahan (1999), lighting in a digital scene aims to enhance mood, atmosphere and drama (Callahan, Citation1996, p. 1).

Whatever definition and features are argued there is a general agreement that suspense is a key issue in terms of emotional gratifications. Reactions in response to this type of entertainment are positively related to enjoyment (Oliver, Citation1993, p. 315), having a big impact on the audience's immersion and suspension of disbelief (Hsu et al., Citation2014, p. 1359). The general pattern indicates that readers find literary texts interesting when the content is suspenseful, coherent, and thematically complex, accounting for approximately 54% of the variance in situational interest, where suspense made the single greatest contribution, explaining roughly 34% of variation (Schraw et al., Citation2001, p. 445). This feature is not constrained only to the classic narratives field: Klimmt et al. (Citation2009) experiments within the video-games industry conclude that players find suspenseful games versions more enjoyable than non-suspenseful ones (p. 31). All of this suggests an evident interaction of negative valence and liking (Altmann et al., Citation2012, p. 2).

In the example of Section 2, the treatment of decorative elements is shown in order to modulate suspense. In particular, the storm and the thunder. As introduced, these are objects that in principle do not seem to interfere in the main plot, but rather give more context and ambient. The rest of this paper is focused on the perception of suspense triggered by this kind of objects.

Computing the impact of decorative elements on a general perception of suspense requires providing the system with the ability to measure the cognitive impact of each one of the elements. This implies that each decorative element is assumed to trigger a certain emotional response on the audience. As such, predicting the influence in terms of suspense needs identifying the emotional properties of each decorative element.

While the interrelation of the elements between them is also a phenomenon to study, the current research has focused on providing an approximation based on the elements as independent entities. The independent amount of suspense of each decorative element is then proposed as a baseline for further research contemplating, for instance, the aspect of the mutual influence of multiple decorative elements.

3.1. Emotions associated to concepts

As aforementioned, the impact of decorative elements seems to be strongly related to their semantics and the emotional characteristics that, on average, they trigger on the audience (Delatorre et al., Citation2016b, p. 28). If we may demonstrate this hypothesis, a computational system predicting the suspenseful reaction must include this information. In order to prove it and to include this information in the system, the Affective Norms for English Words (ANEW) has been used. ANEW is an extensive list that contains a number of emotional aspects of the included terms.

The American ANEW was created as the result of an experiment of Bradley & Lang (Citation1999). Participants were asked for the emotional affection of 1034 words. To evaluate the set of words, participants selected each dimension painting in a 9-point rating scale represented by the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) (Bradley & Lang, Citation1994). Devised by Lang in 1980, the SAM model is a non-verbal, pictorial assessment technique that directly measures the emotion conceptualising it in three dimensions: valence (or pleasure, ranging from pleasant to unpleasant), arousal (ranging from calm to excited) and dominance (or control, ranging from in control to out of control) associated with a person's affective reaction to a wide variety of stimuli (Bradley & Lang, Citation1994, p. 49; Lang et al., Citation1997, p. 39). ANEW experiment has been replicated for several languages as French, Finnish, Dutch, Portuguese or Italian (Eilola & Havelka, Citation2010; Monnier & Syssau, Citation2014; Montefinese et al., Citation2014; Moors et al., Citation2013; Soares et al., Citation2012).

Emotional valence describes the extent to which something cause a positive or a negative emotion (Citron et al., Citation2014, p. 79). In terms of the story, an element has a negative valence when it pushes towards a negative outcome. It has been extensively investigated the paradox in that texts with negative valence are perceived as more amusing than texts with neutral or positive valence. Citing Altmann et al. (Citation2012), the emotional reaction to uncomfortable expositions has been studied in media psychology regarding different narrative contexts (p. 2). These contexts include tragic television news and crime drama (Raney, Citation2002; Raney & Bryant, Citation2002; Zillmann et al., Citation1998), where enjoyment of unpleasant stories is not limited to a happy endings (Schramm & Wirth, Citation2010). Suspense increases while the negative outcome probability (Iwata, Citation2009, p. 107, 137) and the negative valence effect of the environment features do (Frome & Smuts, Citation2004, p. 19).

The second dimension is the arousal (Berlyne, Citation1960), that refers the intensity of the emotion (Citron et al., Citation2014, p. 79). This dimension seems to have a similar effect on the audience that the pattern found in negative valence. So, the higher the discomfort during the tension phase, the higher the pleasure in the moment of resolution (Lehne, Citation2014, p. 82). Novelists and narratologists agree with that the duration of this intensity has an important role in this tension. “Suspense” comes from the world “suspend”. Its etymology suggest that the more suspense is wanted, the longer suspend the scene is needed (Obstfeld, Citation2000, p. 106). Presenting the outcome a little later than expected (de Wied et al., Citation1992, p. 325) is a key that relates suspense and timing.

Finally, the third dimension, variously called dominance, control or power, reflects the degree of control an individual feels over a specific stimulus and extends from out of control to in control (Montefinese et al., Citation2014, p. 888).

Lexical and semantic aspects are taken into account to check the affective perception of a concept. For example, Hermans et al. (Citation2001) and Ochsner et al. (Citation2009) demonstrated that the use of the adjectives changes the mode which the reader process a term, checking that the time needed to evaluate a concept as either “positive” or “negative” is significantly shorter when the adjectives that accompanies the concept share the same valence (positive–positive or negative–negative; affectively congruent) as compared to trials in which they are affectively incongruent (Hermans et al., Citation2001, p. 144). In terms of background, a similar effect was observed by Liu et al. (Citation2013), who found dependencies between the emotional evaluation of a word and the emotional context (Liu et al., Citation2013, p. 390). Besides, supported by Gerrig & Bernardo (Citation1994), an object varies its emotional influence in the scene once the reader identifies it as decorator, not as active part of the plot (p. 467). Our evaluation (described in Section 5) has been run against Spanish speaking evaluators. Thus, the English version of ANEW, even with direct translations, is suboptimal. Performed by Redondo et al. (Citation2007), the Spanish version of ANEW was made for 720 participants (560 women and 160 men) using the same words and obtaining a remarkable differences with the original American ratings even being the three dimensions linearly correlated respectively between both languages (p<0.001 in all cases) (Redondo et al., Citation2007, p. 602). ANEW lists groups the words in different lexical categories. Within this categories, another not-presented typification can be found according their semantic use. For example, localisations, weapons, person or feelings. At the same time, psycholinguistic and subjective indexes are presented, extracted from the work of Davis & Perea (Citation2005) and Sebastián-Gallés et al. (Citation2000). These factors are familiarity, imageability and concreteness, rating in a 7 Likert scale, and word frequency.

3.2. Gender

The ANEW experiments takes into account ratings contrasts due to demographic features; concretely, the perception of male subjects respect to the female subjects, where there are not significant differences between them in the Spanish experiment (Redondo et al., Citation2007, p. 602). Despite this, on the issue of negative expositions, different emotional reactions and attitudes based on genre preferences are observable. Nolan & Ryan (Citation2000, p. 54) and Cantor & Reilly (Citation1982, p. 82) found that females report a higher level and a greater number of fear reactions than males, who report more anger and frustration responses , but less physiological arousal . Moreover, Burton et al. (Citation2004) affirmed that men show greater priming for affective materials (p. 218). With regard to genre, Nolan & Ryan (Citation2000) detected that males recall a high percentage of descriptive images associated with what is called “rural terror” (a concept tied to fear of strangers and rural places), while females display greater fear of “family terror”, including the themes of betrayed intimacy and spiritual possession (p. 39). Besides, Oliver & Sanders (Citation2004) asserts that women reflects a greater attention to interesting plot than violence (p. 256). Tamborini & Stiff (Citation1987, p. 415) and Robinson et al. (Citation2004, p. 43) found that females likes horror-movies more when a good ending, being the “destructive nature” of horror films what male fans like . In general terms, male viewers reported a greater preference for high-arousal films compared to female viewers, and female viewers reported a greater preference for low-arousal films compared to male viewers (Banerjee et al., Citation2008, p. 87). These differences are not supported for all psychologists: Fischoff et al. (Citation2003) defend that females and males really do not differ in their attraction to the horror film genre respecting to the emotional response to fear ; the difference lies in that males like violence in movies more than females do (Fischoff, Citation1994). Nevertheless, they point differences of threats preferences, where males are significantly more likely to favour monsters because of their killing capacity (Fischoff et al., Citation2003, p. 414). Beyond this, both genders are basically attracted to the same threats and for similar reasons (p. 402 ). In terms of emotional affection, it may be consistent with punctuations obtained in the Spanish ANEW experiment, where the ranges of ratings did not differ considerably (Redondo et al., Citation2007, p. 603).

Not only the gender of the audience, but character-victim gender and its influence in the audience has also been subject of study. Most of the information about character gender role in suspense comes to us from horror films, specially the slasher genre, where effects as victimisation based on gender has been broadly studied (Carrasco-Molina, Citation2012; Freeland, Citation1996; Linz & Donnerstein, Citation1994; Sapolsky et al., Citation2003; Weaver III, Citation1991; Williams, Citation1984). As said by Freeland (Citation1996), several films seem explicitly to white females as being a certain “victim” status (p. 201). Sapolsky et al. (Citation2003) affirm that, in studied films, females are shown in fear for longer periods of time than males (p. 28), and therefore transmitting more sense of danger. This is corroborated by Weaver III (Citation1991), who found that scenes portraying the death of female characters were significantly longer than those involving male characters. One possible explanation is that male characters are often shown attempting to defend themselves when attacked and, because of this stand and fight reaction, are dispatched in short order. Female characters, on the other hand, often exhibit a flight reaction and, because of their initial elusiveness, delay the ultimate confrontation with their attacker (Weaver III, Citation1991, p. 390). To Linz & Donnerstein (Citation1994), the use of techniques such as these to prolong women's torture but not men's sounds like a systematic gender bias (p. 244). In any case, the difference of gender's treatment is evident enough as to be covered.

3.3. Empathy

Additionally, the way that the victim is described has effect in the empathy. This is defined for Krebs (Citation1987) as the psychological part of altruism (while genes would be the biological part) (p. 88). Cohen (Citation2011) defends the effect of the concern about the character outcome (p. 127). A step further, Doust (Citation2015) includes concern about the fate as implicit concept around the idea of suspense (p. 37). In terms of empathy, there are archetypes who spectator identifies with more than others. For example, Hoffner & Buchanan (Citation2005) found that men identify with male characters whom they perceived as successful, intelligent and violent; whereas women identify with female characters whom they perceived as successful, intelligent, attractive and admired (p. 325). Besides, authors as Hoffman (Citation1977), and more recently de Corte et al. (Citation2007) and Nanda (Citation2013) defend that females may have greater tendency to imagine themselves in the other's place. Additionally and again in terms of physical aspect, the conclusions of the studies of Chiao & Mathur (Citation2010) and Sessa et al. (Citation2013), support that people are more empathic with other people of their same race. According to Hsu et al. (Citation2014), narratives with emotional contents, especially negative, arousing and suspenseful ones, facilitate immersion by inviting readers to be more empathic with protagonists compared with neutral texts, thus engaging the affective empathy network (p. 1356). Nevertheless, Beecher (Citation2007) warns that there is less certainty than imagined concerning the roles of empathy or identification in suspense as pure emotional states (p. 260). The previously cited experiment of Nanda (Citation2013) about empathy was performed using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Proposed by Davis (Citation1980) this index is a commonly used self-report instrument designed to assess empathic tendencies (de Corte et al., Citation2007, p. 235). IRI has been translated into several languages. Pérez-Albéniz et al. (Citation2003) performed the Spanish version. Similarly to the original approach, it consists of 28 questions grouped in four subscales: Perspective Taking (PT), Fantasy (F), Empathic Concern (EC) and Personal Distress (PD). Participants must response how well the item describes them on a five-point scale anchored by 0 (“it does not describe me well”) and 4 (“it describes me very well”).

Finally, according to Oliver & Sanders (Citation2004), it is unlikely that highly empathic people would find this kind of films a pleasurable form of entertainment (p. 246). Respecting to this voluntary exposition to horror/suspense fiction, it may be explained by the emotional gratification provoked by the genre. This discover is endorsed by Hsu et al. (Citation2014), finding that suspense has a big impact on the audience's immersion and suspension of disbelief (p. 1359). As aforementioned, Altmann et al. (Citation2012) proved the existence of an interaction between negative valence and liking (p. 2). Moreover, Palmer (Citation2008) affirms that people who watch horror movies are less fearful than those who do not (p. 25).

4. Related work on automatic suspense generation systems

This section summarised the treatment of suspense in the main computational narrative systems. Given the scope of the proposed model of suspense, the review focuses on generative systems.

MEXICA (Pérez y Pérez, Citation2007) is a program that writes short stories about the Mexicas, the old inhabitants of what today is Mexico City (p. 2). These stories are represented as clusters of emotional links and tensions between characters, progressing during development, and whose operators, intensity and predefined texts are customisable. In MEXICA, it is assumed that a story is interesting when it includes degradation-improvement processes (i.e. conflict and resolution) (Pérez y Pérez, Citation2007, p. 4). Throughout the history, emotional links among the characters vary as a result of their interactions; so, princess healed jaguar knight produces the effect of increasing a positive emotion (gratitude) from the knight to the princess.

MEXICA is an exception in the use of positive emotions to implement the narrative tension. The system works with two predefined types of emotion: brotherly love and amorous love, both ranging from (negative emotion) to 3 (positive emotion). Additionally, 10 types of tension are defined (actor dead, love competition, health normal…), which are generated based on the type and emotional value of each character. The stories search degradation-improvement curves through actions that transform the extent of the tensions.

MINSTREL (Turner, Citation2014), meanwhile, is a complex program that writes short stories about Arthurian legends, implemented on a case-based problem-solver where past cases are stored in an episodic memory (Pérez y Pérez & Sharples, Citation2004, p. 4). MINSTREL recognises narrative tension plots and tries to increase the suspense by adding more emotionally charged scenes, by storing a simple ranking which tells when such inclusion is reasonable; for example, when the action is preserving a life. It uses two strategies for generating suspense: via character emotion and via character escape. In the first one, it is included in the text a sentence that describes the fear of the character about the immediate threat. The second one adds another sentence that reports a failed character's attempt (Turner, Citation2014, pp. 123–126).

Another initiative is Suspenser (Cheong & Young, Citation2006), that creates stories with the objective of increasing the reader's suspense. It provides an intermediate layer between the fabula generation and the discourse generation, which selects the steps of the plot according to their value of importance for the final goal. For this and based on the Gerrig and Bernardo's assumption,Footnote9 Suspenser uses a set of heuristics grounded in the number of paths available for the character to reach its goal, considering optimal the probability of protagonists' success as 1/100 (Cheong, Citation2007, p. 59).

Also based in Gerrig and Bernardo's work, Dramatis proposes an implementation of a system to evaluate suspense in stories that utilises a memory model and a goal selection process (O'Neill, Citation2013, p. 5), assuming that the reader, when faced with a narrative, evaluates the set of possible future states in order to find the best option for the protagonist. With a similar target, Dramatis generates escape plans attempting to “break” the causal links that would reach non-desired goals (typically, the character death) and the reader could predict more easily. To do this, the memory model assigns more relevance to the elements recently narrated than to those mentioned at the beginning of the story.

Finally, we review IDtension (Szilas, Citation2003), a drama project which comes up in order to demonstrate the possibility of combining narrative and interactivity. Unlike approaches based in character's chances or the course of the actions, it conceives the stories based on narrative properties (conflict or suspense).

Suspense is treated by IDtension as a reaction to the obstacles (conflicts), and is correlated to the risk of facing every expected obstacle (high or low risk, without intermediate values). The narrative effects of the tension are calculated by six criteria: ethical consistency, motivational consistency, relevance, cognitive load (influence in the story), characterisation and conflict. Also, the condition is managed by a series of actions as accepting, refusing, congratulate, etc., available for use on/among the characters.

Although their purpose is not the generation of suspense, other proposals include mechanism for its treatment. IPOCL (Riedl & Young, Citation2010) is a kind of POCL planner (Partial Order Causal Link) which is improved by a factor of intention (Intent-Driven) on the part of the characters, denoted by a function intends; the planner attempts to satisfy the intention whenever possible. Indexter (Cardona-Rivera et al., Citation2012), based on IPOCL, offers a model that emulates the reader's memory, allowing use of knowledge previously presented as new (and surprising) information. To end this section, we mention Prevoyant (Bae & Young, Citation2008), that enriches the stories with flashback (past events) and foreshadowing (hints of what is to come) strategies, providing additional data and tension ahead, respectively. For the first strategy, Prevoyand identifies causal links previous to the current event that haven't been described; as to the second, it submits a character or object participant of a future event.

With respect to our goals, the review of the above systems has exposed some comparative limitations. Firstly, we can observe that none of them takes into account the empathy as explicit part of the model, neither physical aspect nor moral and ethical issues. Additionally, as result of the evident limits of the current storytelling systems, the number of possible interactions between the characters and the environment is restricted by its respective internal base of events. In any case, MEXICA allows to redefine the actions.

On the other hand, all of them include arousal to a greater or lesser degree. MEXICA implements an emotional gradual intensity, ranging from −3 to 3, being the only that includes emotional valence both in this range and in the variability of possible interactions. MINSTREL, Suspenser, Dramatis and IDTension do not include the valence either. With respect to IDTension we have not studied the effect of the interactivity narrative in the result of the suspense.

5. Method

In this section, we detail the design of an evaluation based on human subjects meant to support the hypothesis introduced in Section 1, namely that decorative elements influence the perception of suspense.

5.1. Participants

For the textual stories, 63 Computer Science undergraduate students (30 females, 33 males), from University of Cadiz, with ages ranging from 17 and 40 years (M=23.44, ) took part in this evaluation. The evaluation was announced publicly in the University and those wanting to take part in it voluntary enrolled. In order to maximise the collected data, all volunteers were accepted. A total of 3787 data were collected. 34 values were missing due to not clear answers or empty cells.

The 3D environment was tested by 17 evaluators (4 females, 13 males), with ages ranging from 20 to 40 years (M=25.29, ). This set of subject was also formed by Computer Science students from University of Cadiz that voluntary enrolled. There was no overlap between the subjects of the textual stories and the 3D environment.

For the test with the 3D environment, 474 records were collected. 2 values were missing due to not clear answers or empty cells. All participants were Spanish native speakers. The variations of each scenario were randomly computed for each execution and subject.

In both tests, age variability was not controlled a priori. Instead, it was hypothesised that, given the kind of models under evaluation, the impact of age would not be significant. The obtained results are in line with this hypothesis.

The assessment was carried out in a classroom, and it was guided by the authors as experimenters. The subjects were informed in the introduction of the questionnaire about the purpose of the evaluation. They were also informed that anonymised data was going to be collected and that going on with the evaluation implied the acceptance of these conditions. All evaluators agreed. There was no compensation for participating in the evaluation.

5.2. Collecting emotional semantics for decorative elements

As introduced in Section 3, many experimental results have shown that small but carefully selected changes to a virtual environment can influence the vividness of the representation and the experience of the user. Following this idea, this section describes the creation of a computational model of the influence of decorator elements on the perception of suspense. In order to get it, the model design has to take into account the variability of the effects in the individual reader of a story.

Since all the evaluators are native Spanish speakers, the words used in the evaluation were obtained from the Spanish adaptation of ANEW (Redondo et al., Citation2007), that measures the three emotional dimensions (valence, arousal and dominance) for each word. According to the working hypothesis, we have chosen the three groups of words from it: words that increment suspense, words that decrement suspense and neutral words (those not influencing suspense). The general formula to measure the level of suspense of a word is given by those emotional dimensions. Supported by the SAM model, Spanish ANEW study uses 1 to 9 ranging for valence, arousal and dominance.

The design of the human-based evaluation aims to introduce a suspenseful situation. In this position, two variables are analysed: the influence of each independent object in the scene, and the context in which the scene occurs, as we defend that the emotional affection is not only due to the composition of individual elements, but the background too. In fact, ANEW contains backgrounds punctuations, as localisations, climatology or sounds.

To reduce the quantity of variables and complexity of the experiment, only decorative objects has been analysed. Around these objects, possible collateral effects are tested to respect of character gender in the introduced situation, participant features (empathy, gender, age and genre preferences) and word features (length, familiarity, imageability and concreteness).

With respect to the decoration, selected words to apply this measure must be clear, specific enough and physically representable. Accordingly, adjectives, colours and verbs have been discarded, as much as generic (as “home”, “toy” or “pet”) or non physical concepts (as “victory”, “intellect”, “truth” or “hug”). Another selection criteria takes into account to avoid that any element has an evident potential to intervene in the unfolding of the plot (e.g. “rifle”, “vampire” or “venom”). We are measuring the effect of the decoration; thus, the suspect of future participation of an element in the outcome goes further: in this scenery, the impact of the object as beneficial or harmful for the characters may overlap the emotional effect of the concept by itself, independent of its function, impeding the measure of this effect separately. Furthermore, a third criteria is based on avoiding elements logically derived from other elements of the scene. In this case, the only occurrence found has been “coffin” respect to “corpse”. The last criteria requires to select elements with a chance to be presented in the context. For example, “shark”, “bus” or “volcano” can not be included in a common room, which is the proposed localisation for the evaluation.

From these criteria, we have selected a set of objects. The subset has been chosen in order to keep the size reasonable for the evaluation (25) and in order to provide coverage to a broad range of valence, arousal or dominance. Table shows this set. First and second columns introduce the element name in Spanish (for the evaluation) and English (translated for this paper). The rest of the columns represent the mean valence, arousal and dominance, respectively.

Table 1. Selected ANEW concepts.

In order to support the hypothesis that these three dimensions actually make a good prediction of the influence of decorative elements on the perception of suspense, two sequential tests were run. The first test was run with short textual stories. After the analysis of the results, with the aim of comparing the results in a different narrative context, a second test based on a 3D virtual environment was performed. In both cases, the evaluators were given the stories in which only one decorative element was included on each step (that is, 25 variations). In the textual stories, references to the element were given, whereas 3D models or texture changes were included in the short 3D interactive simulation. The participants were queried about the relative suspense they perceived for each variation, and this was compared against the theoretical suspense computed from the ANEW scores of the concepts corresponding to the decorative elements included.

5.3. Design of evaluation based on textual stories

The evaluation has been designed as a paper and pencil process, starting with demographic information as gender, age and career. Next questions are relative to the preference to respect to suspense genre.

I watch horror or thriller films

I like horror films

I like thriller films

Both questions could be answered with one of four possible answers: never, a few per year, many per year, many per month for the first; and none, a little, a lot, I'm a fan for the second and third. The objective of these questions is to contrast any influence in suspense perception due to a possible overexposure or dislike to the genre. Later, with the objective to check the sensitivity of the participant to the situation of the main character, we introduce the 28 questions of the IRI questionnaire in its Spanish version. In this way, we consider the effect of the empathy / sympathy of the participant as factor to study its influence in the suspense feelings.

Once the demographic and personal questions are presented, the evaluators are advised about to the immediate beginning of the suspense excerpt. In order to avoid the effects of the ambiguity of the term, we facilitate the definition of de Wied (1992): “a high degree of certainty of a negative outcome” (de Wied et al., Citation1992, p. 325), aforementioned in Section 3. After this point, the content is presented to the evaluators. For the textual stories, the test invites to the participant to imagine the scene and rate the level of suspense.

A man enters a room hastily. He feels that something horrible pursues him and he is very scared. He closes the door trying not to make noise. There is no one else.

The lack of specificity about some aspects of the story was intended. The objective was to give freedom of choice to imagine what the threat, victim and plot are. The description of the situation is as less concrete as possible, aiming the reader to be free to imagine threat, victim, room and plot as prefer. Likewise, there are not references to physical appearance nor typification of characters. We have used only two words to create suspense (one for the thread and one for the victim): “horrible” and “scared”. Similarly, we have included the minimum information to related the plot to the three dimensions of emotional affection (Delatorre et al., Citation2016b, p. VII): [negative – valence], [anxiety – arousal], [inescapable – dominance].

In order to avoid influence in different ways depending on the reader gender (mentioned above in Section 3), we have obtained these adjectives from the frequency of use of key words from descriptions for men and women (Nolan & Ryan, Citation2000). The adjective and the victim feelings are based on the words of their classes that imply less difference between genders. No other adjectives were used in the evaluation: threat intensity or victim vulnerability are not specified in order to avoid the influence of the participant's empathy.

In this manner, rising action is the preferred introduced at the exposition/rising action stage of Freytag's pyramid and exposition/complication of Knobloch et al. About the plot, the scene describes a very primary situation, locating at the exposition/rising action stage of Freytag's pyramid (Citation1894) and exposition/complication of Knobloch et al. (Citation2004). Other stages as new situation of Hauge's plot (Citation2011) or snake plot's temporary binding (Tilley, Citation1992) can describe the scene in terms of structure too. The plot is paused to avoid rising action or any progress of the conflict. In order to reduce the perception of actions over decoration in the event, the threat keeps outside of the localisation and sightly far in terms of outcome proximity.

The text has two variations by using both possible characters' genders, female and male. The rest of the scene remains. For indicating the effect of suspense, we used a 1–9 range, having a direct comparison of results with Spanish ANEW and preventing the possible collateral effects of another range of punctuation.

Further, the list of decorative elements was presented in the evaluation, asking for the participants to evaluate their first suspense perception and the variation of the suspense level for each object introduced. The instructions include an advise about that a current element was the only in the scene at the same time, to avoid a possible effect of relation between objects. Likewise, the list of elements was randomly shuffled to avoid the “sequence effect”. This way, there are 30 randomised sets of elements; each set is applied to each of the two possible story variations, giving a total of 60 different tests. Every possible test combination gender/order were filled by at least one participant. Tests were randomly distributed to get a similar distribution of characters' genders with respect to participants' gender.

5.4. Design of the model evaluation in a 3D environment

Our sample is based on the first-person game P.T. (2014), which was a playable teaser of Silent Hills (the project was eventually cancelled). In this game, the player is pushed to walk cyclically through a indoor corridor, where elements become more strange and unease every loop (Ruiz & Bienvenido, Citation2015, p. 108). As the player progresses, her will discover with insects, blood stains, dirt, darkness, rain or red lights (Ruiz & Bienvenido, Citation2015, p. 108). Suspense is hypothesised to increase after every.

The virtual environment used in the second evaluation has been created by two external developers. The Unity Game Engine, version 5.3.2 was used. A random generation algorithm was implemented in C# to present every variation in random order, integrating it with the game further. There are obvious differences from the original video-game P.T., mainly the graphics quality and the absence of plot. Figure shows a comparison between snapshots of the 3D virtual environment and of P.T.

Figure 2. A comparison of the version of the corridor in the 3D environment used in the evaluation (up) and the inspiration taken from the demo P.T. (down). (a) 3D environment developed for the evaluation and (b) Scene from the video-game P.T.

Initial questionnaire and the information presented were the same as the one used for the textual stories evaluation: the same definition of suspense and the same idea that the threat is left outside. Only two differences must be reported: (a) empathy and suspense preferences were not measured because the previous evaluation evidenced that it was not sufficiently significant; (b) additionally, given that the 3D environment is played as a first person experience, no specific gender was given to the main character.

Each loop of the corridor is exactly the same, except for the variation of one single decorative element, taken from the list used in the textual stories. The map starts a small hall, whose only exit takes the player to a corridor ending in a small square room, where the decorative elements are shown. In order to implement the environment, the P.T. game has been taken as an inspiration. Some elements present in P.T. were not included in the 3D environment in order to avoid a excessively loaded scenario. Burned photographs, ashtrays, pills or cockroaches, for instance, have been removed because they represent concepts with a highly negative valence and dominance. Alternatives (other corridors, doors) have been removed to help the player concentrate on the elements in the scene. The only decoration then consists on neutral elements in terms of arousal, dominance and valence. Additionally, while P.T. happens during the night, the 3D environment happens during the day. This is so because intensity approximates to its average value during the day, thus making it slightly more neutral (Moors et al., Citation2013).

Translating ANEW concepts to actual 3D objects in the environment required a few design decisions. In order to choose the appearance of each one of them, clarity was preferred to ambience. Placement of each element was also carefully selected in order to provide instant visibility plus an acceptable degree of normality. Same concepts like “germ” or “dirt” were difficult to represent, given that they do not refer to specific, isolated objects. Table describes the visual design from the concepts to the 3D environment.

Table 2. Visual design of the concepts.

6. Results

This section details the obtained results for the experiments described in previous Section 5, comparing the outcome of the textual stories and the virtual environment. For all measures, the criteria for statistical significance was set at

.

6.1. Decorative elements

In this part, we present the global analysis of eight different possible factors which may be related to decorative objects' scores: the three dimensions of emotional affection (valence, arousal and dominance) Lexical frequency, familiarity, imageability and concreteness are included due to they are required to the translation from objects to their mental representation. As a non parametric 9 Likert scale has been used for scoring suspense of decorative elements, correlations have been analysed using Spearman's test (Jamieson, Citation2004, p. 1217) with the medians of each object scores. Table shows medians, means and standard deviations for the decorative objects in both tests.

Table 3. Means and medians of suspense perceptions for each object.

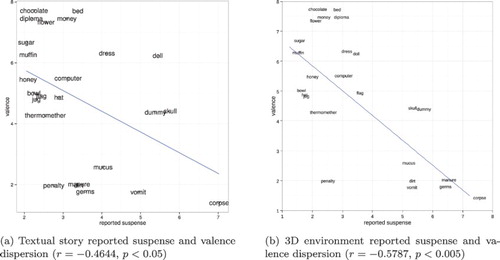

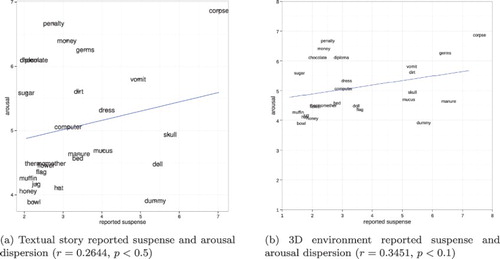

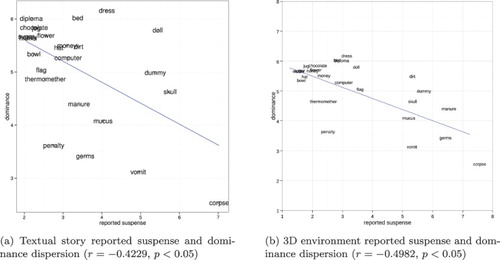

With respect to the dimensions of emotional affection, moderate significant correlations have been found between scores and valence (r=−0.4644, p=0.0193 for the textual stories; r=−0.5787, p=0.0024 for the 3D environment) and dominance (r=−0.4229, p=0.03521 for the textual stories; r=−0.4982, p=0.0113 for the 3D environment). However, we may not ensure that arousal provoked by objects influence their evocation of suspense by itself (r=0.2644, p=0.2015 for the textual stories; r=0.3451, p=0.0912 for the 3D environment).

Table shows the information of linear correlations between pairs about emotional affections and participant suspense punctuations. Figures –, respectively, show the relations between reported suspense and the value of each emotional affection dimension both in the textual stories (subfigures a) and the 3D environment (subfigures b).

Figure 3. Comparison of correlation between suspense and valence (textual story and 3D environment). (a) Textual story reported suspense and valence dispersion (r=−0.4644, p<0.05) and (b) 3D environment reported suspense and valence dispersion (r=−0.5787, p<0.005).

Figure 4. Comparison of correlation between suspense and arousal (textual story and 3D environment). (a) Textual story reported suspense and arousal dispersion (r=0.2644, p<0.5) and (b) 3D environment reported suspense and arousal dispersion (r=0.3451, p<0.1).

Figure 5. Comparison of correlation between suspense and dominance (textual story and 3D environment). (a) Textual story reported suspense and dominance dispersion (r=−0.4229, p<0.05) and (b) 3D environment reported suspense and dominance dispersion (r=−0.4982, p<0.05).

Table 4. Pairs of suspense and dimensions of emotional affection correlations. For each pair A/B, A corresponds to the textual stories, and B to the 3D environment.

Behaviour of arousal dimension presented in Table is as expected, as its correlation to the others dimensions in Spanish ANEW is not linear, but quadratic (r=0.5220, p<0.0001), representing 27.1% of the varianceFootnote10 (Redondo et al., Citation2007, p. 602). At the same time, valence is highly correlated to dominance. Similar U-shaped distributions have been reported by studies providing affective ratings for words in other languages (Bradley & Lang, Citation1999; Eilola & Havelka, Citation2010; Monnier & Syssau, Citation2014; Soares et al., Citation2012).

Further, we have found a significant correlation between the suspense scores of the first impression and the sum of scores of the each decorative object (r=0.4844, p=0.0165 for the textual stories; r=0.6374, p=0.0059 for the 3D environment). It remarks the importance of that initial impression in terms of evaluating the rest of elements in the scene.

Finally, in textual stories not enough significant correlations were found between participant punctuations in lexical frequency (r=0.0147, p=0.9443), familiarity (r=−0.1778, p=0.3953), imageability (r=−0.1594, p=0.4465) or concreteness (r=−0.2189, p=0.2931). Independence hypothesis can not be rejected for this features.

The results are considered to be reasonably robust given the fact that the numbers for the textual stories and the 3D environment are reasonable similar, with only small differences assumed to exist due to the different amount of evaluators and the acceptable error. In the textual stories, dominance plays a more intense role on the regression model whereas the 3D environment sees a strong influence of both dominance and valence. Given that the correlation between dominance and valence is also significant, this is considered acceptable.

6.2. Additional analyses

Here below, we present the analysis of other aspects not covered in the hypothesis but which could potentially influence suspense. These are gender, empathy index, and other characteristics as age, suspense exposition and preferences about suspense and horror.

6.2.1. Gender

We conducted a Student's t-test for analysing the participant gender influence in the perception of the subject about suspense decoration (Table ). With respect to the participants, an analysis of variance reveals that, in both genders, we may not conclude variances are different in terms of the means of decorators' scores (,

for the textual stories;

,

for the 3D environment) neither the first impression (

,

for the textual stories;

,

for the 3D environment).

Table 5. Mean differences in participants and characters by gender.

The same tests were run to check the influence of character gender in the textual evaluation, with similar results respecting to equality of variances when comparing man (N=33) with woman (N=30) in the plot. Thus, there is a weak and not significant correlation between character gender and the means of decorators' scores (,

), and a less weak but significant evidence of correlation is obtained with the first impression (

,

). This test has not been performed in a 3D environment, due to the first person point of view of the participant, which makes visually impossible to identify the gender.

Finally, for the textual stories a two-way ANOVA was tested to compare the effects of both factors together, participant's gender and character's gender. Not conclusive relations were found (F=0.7724, p=0.4653). Consistent with the previous tests, it does not seem that men and women differ in their perception of suspense, with independence of character's gender.

Accordingly, we have no evidences that participant gender affects to perceived suspense in our scene. Nevertheless, gender of the (potential) victim seems to have impact enough by itself. As there is not correlation with the means of the decorators' scores, we may not say that this impact concerns to the decoration, but directly to the character conjuncture.

6.2.2. Empathy

An analysis of correlation between IRI and reported suspense reveals hardly any statistically significant influence in the textual evaluation. No clear dependency is shown for the means of decorators' scores, (r=0.0640, p=0.6299),

(r=0.1146, p=0.3876),

(r=0.1546, p=0.2424) nor

(r=−0.0826, p=0.5339). With respect to the first impression of the situation,

(

, p=0.5239),

(r=−0.0848, p=0.5270) and

(r=−0.0823, p=0.5389) the same behaviour is exhibited. However, we can find a weak relation and significance when correlated the

(r=0.1936, p=0.0896). Even it is not significant enough, it is remarkable the difference with the other empathic measures, which has sense considering that EC is the only based on concern.

Due to the results were not significant enough, this feature was not evaluated in 3D evaluation.

6.2.3. Age, suspense exposition and preferences

We have analysed age, frequency of exposition, liking for suspense and liking for horror in the textual evaluation. No statistically significant correlations have been found for most of them: age (,

;

,

), frequency of exposition (

,

;

,

), liking for suspense (

,

;

,

) nor liking for horror (

,

,

,

). However, analysis shows that liking for horror presents a weak but significant enough influence in the perception of decorative elements (

,

). Nevertheless, taking into account the rest of analysis of exposition and preferences, we may not consider this result as conclusive.

For the same reasons that IRI questionnaire was not tested in the 3D environment, suspense exposition and preferences were not significant enough to be asked to the participants. Age was reported due to basic demographic classification, neither having found any significant relation (,

;

,

).

7. Computing a linear model

The hypothesised correlation between the perception of suspense and valence, arousal and dominance is reasonably supported by the empirical study. This enables the application of regression algorithms to compute a predictive statistical model.

In order to do this, the data gathered from the subjects were used to train a linear regression. Given the discrete values of the rating of the suspense provided by the user (9 points Likert-like scale), both models were trained by using valence, arousal and dominance against the median of the suspense ratings.

For textual stories, the RMSE error for the linear model was 1.1106 (the data ranged from 1 to 9), the linear regression provided coefficients for valence (0.0684), arousal () and dominance (

), with an intercept of 8.088. For 3D environments, the RMSE error for the linear model was 1.516, the linear regression provided coefficients for valence (

), arousal (0.2248) and dominance (

), with an intercept of 6.8140, balancing the influence of valence and dominance in a better way. Correlation between the result of applying both linear models for the evaluated terms is r=0.9007, p<0.0000.

In both cases, while the learning data is relatively scarce, this supports the consistency of the approach and the plausibility of modelling suspense as a function of valence, arousal and dominance of words in these scenarios.

Taking this model into account, we propose a decorator algorithm based on the following two simple rules. Being ψ the result of the function adapted by the linear regression (textual or 3D, depending on the context), (a) the more elements that increases suspense are presented () and, secondly, the higher their ψ factor are, the more suspense is evoked; and (b) the more elements that decreases suspense are presented (

) and, secondly, the lower their ψ factor are, the less suspense is evoked.

Having tested that the previously presented approach is valid, this section proposes an algorithm to adapt a scene with decorative elements so that the output scene theoretically triggers an average perception of suspense on the audience that approximates a reference suspense value. This is an important part for the aim of the model introduce in Section 2 to adapt the suspense to the intensity input

.

Keeping this in mind, minimum effect will be evoked when all objects with are in the scene, and no object with

. Maximum suspense will be evoked when all objects with

are in the scene and no object with

is present in the scene. Being S the number of elements candidates to be in the scene with

, and R the number of them with

, the deterministic process shown in Algorithm 1 returns a set with all the combinations of objects ordered by suspense level, from lowest to highest.

8. Discussion

8.1. Results analysis

Despite the common idea that gender of the reader influences her perceived suspense (as detailed in Section 3), no clear differences have been reported in the data analysis. Although this fact seems evident in textual stories (,

), the 3D evaluation does not allow to reject the influence of the participant's gender in our virtual environment: even results are not significant (

,

), the number of female subjects may be consider small enough to obviate the moderate evidence of correlation. Despite of it does not invalidate the general conclusions of this study, we consider that this effect must be review more closely in forthcoming papers.