ABSTRACT

Giving the rising interest in naturally grown foods; several studies have contrasted various features of organic and conventionally grown foods in relation to consumer attitudes, perceptions, and preference for organic foods. This paper aims to explore consumers’ willingness to consume organic foods; the extent and attributes of consumer knowledge and awareness about organic food as well as consumer attitudes and preferences for organically grown foods. Articles from different peer review journals were used to develop this paper. The findings of this paper show that human health, food safety, attitudes and perceptions and willingness to pay for a price premium are some of the factors influencing consumers’ willingness to consume organic foods. Therefore, there is a need to create more awareness in the food industry relating to the health benefits of consuming organic foods.

1. Introduction

The rising interest in foods that are grown organically is gaining attention in both developed and developing countries (Chander et al., Citation2011; Mie et al., Citation2017; Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2019). This attention is in response to several factors such as concern about the environment, food safety, animal welfare, as well as human health (Barański et al., Citation2017; Harper & Makatouni, Citation2002; Magnusson et al., Citation2003; Rizzo et al., Citation2020). These aforementioned trepidations, together with perceived organic consumer conduct, led to identify various kinds of organic shoppers, such as food phobics, humanists and welfare enthusiasts, environmentalists, hedonists, and healthy eaters (Davies et al., Citation1995). The interest in organic food production has driven many studies (Gomiero, Citation2018; Hurtado-Barroso et al., Citation2019; Niggli et al., Citation2008; Röös et al., Citation2018; Shafie & Rennie, Citation2012) comparing aspects of organic and conventionally grown foods. This has also led to the growing interest amongst various stakeholders such as policy makers and consumers not only to determine the level to which there is a scientific root for assertions in backing of organic produces, but also to combine and assess the various experiential studies and discoveries. For instance, Bourn and Prescott (Citation2002) provided an exceptional appraisal of numerous studies () comparing selected biophysical and associated quality aspects of organic and conventionally grown foods. Similarly, Woese et al. (Citation1997) and Bartosz (Citation2013) evaluated a number of studies by means of physico-chemical quality attributes for several food categories, comprising dairy products, nuts and oil seeds, meat and eggs, cereals and cereal products, wines, bread, potatoes, beer, vegetables and vegetables products and fruits.

Table 1. Some quality attributes of organic and conventionally produced food product.

The imminent prospect of organic production will depend, to a great magnitude, on consumer demand (Greene et al., Citation2017). Therefore, there is a need for a consumer-enlighten technique in understanding the importance of organic food production that will benefit the consumers and also increase the market dynamics for organic products. Although this varies across continents and regions of the world, a clear understanding of consumer willingness as well as the drives stimulating actions in responding to naturally produced foods is vital. This review is important so as to justify the various attributes of organically grown foods in relation to consumer willingness for organic foods.

2. Comparison of organic and non-organic product

Identifying the attributes associated with organic foods by visual inspection alone may be difficult to ascertain (Yiridoe et al., Citation2005). Majority of the organic food consumers buy organic produces because of a belief associated with the uniqueness of the products compared to conventionally grown ones (Denver & Christensen, Citation2015; Hughner et al., Citation2007; James, Citation2006; Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Onyango et al., Citation2007; Quah & Tan, Citation2009; Yiridoe et al., Citation2005). Viewing it in another way round, why some consumers do not buy organic produces is associated with a belief that such produces are not healthier than their conventional counterparts (Jolly et al., Citation1989; Watson, Citation2012). As a result of these beliefs contrary to consumers’ line of argument, there is, therefore, continuing interest and argument about whether foods that are produced organically are better than and or the same from conventionally grown counterparts and, if so in terms of what attributes (Yiridoe et al., Citation2005).

Studies, such as (Seufert & Ramankutty, Citation2017; Yiridoe et al., Citation2005; Zahaf, Citation2015), have assessed whether there are discrepancies between conventional and organically grown foods from the view of both the “producer” (supply side) and the “consumer” (demand side). (Yiridoe et al., Citation2005) argued that on the production side, emphases are usually laid on profitability, yield, and producer price comparison. In contrast, studies on the demand-side (for instance, Bartosz, Citation2013; Bourn & Prescott, Citation2002; Woese et al., Citation1997) have examined the differences in terms of “biophysical, and chemical features,” and consumer preferences. However, the importance of this review is on consumer demand (that is the willingness to consume organic food). Therefore, it is important to have a clear understanding on why consumers are willing to consume organic foods.

3. What non-monetary features are the key to organic consumers?

There are several non-monetary features that organic food consumers consider when comparing organic produces with conventionally produced alternatives. These non-monetary features that influence shopper preferences between organic and conventionally grown produces are food safety, nutritive, and sensory attributes (Aigner et al., Citation2019; Bourn & Prescott, Citation2002; Zepeda & Li, Citation2007). A number of studies (Bordeleau et al., Citation2002; Dangour et al., Citation2009; Palupi et al., Citation2012; Smith-Spangler et al., Citation2012) have used these attributes in comparing organic foods with conventionally produced alternatives. Notwithstanding, consumers normally associated the quality attributes of produce with its appearance (Petrescu et al., Citation2020). The finding of Goldman and Clancy (Citation1991) indicates that there is an association between consumer eagerness to accept blemishes and organic food purchase behaviour. Lin et al. (Citation1996) argued that appearance has a less effect amongst consumers with a high choice for organic and pesticide-free produces.

Product taste that is (flavour), storage life as well as freshness are other attributes that contribute to purchasing decisions of organic shoppers (Bonti-Ankomah & Yiridoe, Citation2006; Grzybowska-Brzezinska et al., Citation2017; Nagy-Pércsi & Fogarassy, Citation2019). However, there is contrasting experimental proof relating to the role that shelf-life, taste, and freshness play in consumer decision-making. For instance, the studies of (Jolly & Norris, Citation1991; Sparling et al., Citation1992; Watson, Citation2012) reported that consumers observe no variation in the taste of organic food as against conventionally produced ones, while studies such as (Denver & Christensen, Citation2015; Stoleru et al., Citation2019; Zhao et al., Citation2007) reported a better taste for organic products. Sparling et al. (Citation1992) further argued that the disparities and deductions on storage life, taste, and freshness, where they exist, tend to be associated to the existing “organic versus nonorganic” food buying behaviours of the survey respondents.

In general, the various comparative reviews indicate contrasting deductions with regard to the nutritional utility of organic produces. Several studies (for example, Domagała-Świątkiewicz & Gąstoł, Citation2012; Gastoł & Domagała-Świątkiewicz, Citation2012; Lairon, Citation2011; Lombardi-Boccia et al., Citation2004; Palupi et al., Citation2012; Srivastava & Hu, Citation2019; Worthington, Citation2001) revealed that organically grown foods have a smaller amount of nitrate content and higher mineral and dry matter contents as compared to non-organically grown foods. Additionally, Clark (Citation2002), Crinnion (Citation2010), Johansson et al. (Citation2014), Mie et al. (Citation2017) revealed that organically grown products contain a higher vitamin C content, while the findings of Esch et al. (Citation2010) reported a higher level of vitamin C content also in non-organically grown produces. The differences in findings attributed/associated with factors like storage conditions and maturity at harvest (Dangour et al., Citation2009; Wunderlich et al., Citation2008). Similarly, the contrasting findings may also be associated with differences in research approaches and research conditions (Lester & Saftner, Citation2011). For instance, (Ahmed & Stepp, Citation2016; Bourn & Prescott, Citation2002; Lester & Saftner, Citation2011) highlighted that soil type, duration of the experiment, crop variety, post-harvest practices, climate, and statistical design can all have an effect in the nutritional and sensory features of a particular product. Therefore, it is important for future efforts at comparing organic and conventional production procedures and products to control for, or address, such methodological and research plan issues. However, there is no accurate or understandable association between the various findings and the place where the studies were carried out. As a result of the inconsistency in findings, some researchers propose that climate and soil type may influence nutritional and sensory features of foods, under a cross-examination of certain crops within related regions and/or circumstances they signify differences in some of the results (Benbrook et al., Citation2008; Hornick, Citation2010; Tuomisto et al., Citation2017).

Other studies (Maffei et al., Citation2016; Merlini et al., Citation2018; Worthington, Citation2001), which examined a perception that organic foods tend to have lower chemical and micro-organism pollution than foods that are produced conventionally, also report differences in deductions. As a result of the differences in conclusions, it is not clear that, in a general sense, whether organically produced foods are safer than foods that are grown conventionally. Perceptions relating to the fact that organically produced foods are associated with lower or free from chemical materials are also occasionally queried (Hamzaoui-Essoussi & Zahaf, Citation2012; Hughner et al., Citation2007; Yiridoe et al., Citation2005), as a result of the potential for pollution during processing, and the probability of putting together organic and conventional produces in the food supply chain. Some studies (for instance, Ingham et al., Citation2004; Johannessen et al., Citation2005; Machado et al., Citation2006; Sheng et al., Citation2019) allude that there is a probability of organically grown food carrying a higher risk of micro-organism contamination than conventional produces due to the increased use of manure in organic agriculture which can increase the rate of occurrence of contamination from pathogens like Escherichia coli and Salmonella species. Nevertheless, (Davis & Kendal, Citation2005; Park et al., Citation2013) argued that such risks can be minimize with appropriate management practices.

Lessening this risk necessitates effective prevention approaches. These approaches centre on lowering and removing the micro-organism, starting from the field of cultivation and in the kitchen (Davis & Kendal, Citation2005). Davis and Kendal (Citation2005) further added that the following procedures can greatly minimize an individual’s risk for E. coli contamination.

Location of the garden – garden should be located a distance from animal hutches (livestock or pet) and from manure or compost piles.

Water usage during farming operation – the use of water is not only for irrigation purposes but also to supply liquefied pesticides and manures. However, to minimize the effect of E. coli pollution, clean water should be used to carry out these operations. In the absence of clean water, well-water can be used because of the lesser possibility for E. coli pollution than surface water from ponds, canal channels or streams. It is essential to avoid direct contact of possibly polluted water with vegetables or fruits you intend to harvest.

Management of manure – manure is regarded as a superlative enricher and soil restorative. It is advisable not to put in garden-fresh manure directly to the soil in one’s vegetable or fruit garden. Composting manure appropriately will kill most E. coli. However, for a manure heap to be composted appropriately, the following necessities must be put in place:

Regular mixing of the manure – this is essential not only for airing but also for ensuring that the whole pile has attained the normal temperature.

Monitoring the temperature – “long-handled thermometers” can be used to carry out this goal. It is required that an optimal temperature between 130 and 140 degrees Fahrenheit must be attained for at least 2–5 days of heating cycles; and compost must be mixed in-between cycles.

After composting, leave the compost to heal for 2–4 months before mixing it with the soil. This allows the advantageous bacterial to destroy the disease responsible for these bacteria.

Avoid the application of manure to growing food crop.

Wait for 120 days from the time of manure implementation to crop harvest. However, this can be safely reduced to 90 days if the edible part is protected by a shell, husk or pod. E. coli bacteria can survive freezing temperature, so this time requirement does not include periods when the soil is frozen.

All these approaches are said to help inhibit E. coli pollution when using composted manures (Davis & Kendal, Citation2005).

| (4) | After cultivation – ensure washing your hands properly as well as other polluted parts of the body, with warm water and soap. Implements that had been used in mixing or turning compost pile should be washed properly. Avoid using the same implements used for manure management for crop harvesting (for example, gloves or buckets). Manure-polluted clothing, such as gloves and shoes, should be removed before entering into the house and most specifically before preparing food, eating, and or drinking. | ||||

| (5) | Finally, food preparation in the kitchen – this is the final line of protection for stopping the infection from E. coli contamination and other pathogens associated with food poisoning. The following steps are ways of ensuring the safety of food before serving.

| ||||

Some studies (for instance, Chang & Fang, Citation2007; Custer, Citation2018; Poimenidou et al., Citation2016; Sirsat & Neal, Citation2013) have also shown that soaking of fresh produce, such as apples and lettuce in vinegar, is one of the effective ways of reducing E. coli contamination from food. Soak produce in distilled white vinegar for about 3–5 min and stir occasionally. Aftermath, rinse with clean tap water to get rid of vinegar flavour and only wash what is essential instantly. It is, therefore, imperative to note that all these measures from farm management practices to kitchen can help reduce the contamination of E. coli in food.

4. Organic food development status and willingness to consume organic food

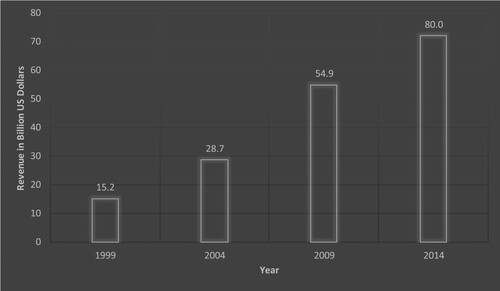

Organic farming is one of the sustainable methods to farming that offers an insight into a paradigm shift from industrial agriculture to diversified agro-ecological systems in relation to food and nutritional well-being of the people (Frison, Citation2016). The reports of Torres and Rampa (Citation2017) on sustainable food systems in the great insights magazine argue that promoting organic production systems can help meet thirteen of the seventeen goals of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Morshedi et al. (Citation2017) indicate that organic farming offers developing nations a broad array of social, cultural environmental and economic benefits. The impact of this could be seen in the global markets for certified organic products that have increased rapidly over the past decades (Willer & Lernoud, Citation2016). shows the growth of the global market for organic food.

Figure 1. Growth of the global market for organic food, 1999–2014. Source: Willer and Lernoud (Citation2016).

In 2014, the global market for certified organic products was estimated to be 80.0 billion US dollars, as depicted in . The global market has increased tremendously from 2009 to 2014. This denotes a 55% growth from 2009 sales evaluated at 54.9 billion US dollars and a 72% growth in 2014 sales estimated at 80.0 billion US dollars, respectively. Willer and Lernoud (Citation2016) highlighted that most sales of the organic products are being generated in countries like North America and Europe. The report added that the two regions accounted for about a third of the global organic agricultural land, but yet they encompass over 90% of the organic products sales. Willer and Lernoud (Citation2016) further argued that organic produces, from regions like Asia, Latin America and Africa, are designated for exports.

Due to growing markets and attractive price premiums placed on organics, several studies in Asia, Latin America and Africa indicate that organic farmers receive higher incomes as compared to their conventional counterparts (Sithole, Citation2018).

4.1. Willingness to pay

Willingness to consume organic food stems from an individual’s willingness to pay. However, willingness to pay is the amount of money that an individual is willing to sacrifice to acquire a product or service (Gumber & Rana, Citation2017). The willingness to pay function establishes the price that a person is willing to pay for a given level of quality at a given price, income and preferences (Lusk & Hudson, Citation2004). Literature suggests that the majority of consumers have a positive attitude towards organic food, but few purchase it on a regular basis due to the price premium attached to it (Aertsens et al., Citation2009; Magnusson, Citation2004; Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Raza et al., Citation2019). Several studies (for instance, Marian et al., Citation2014; Melovic et al., Citation2020; Paul & Rana, Citation2012; Pawlewicz, Citation2020; Shafie & Rennie, Citation2012; Stolz et al., Citation2011) have observed that price premium is one of the main obstacles in the purchase of organic food, while the studies of (Aguilar & Vlosky, Citation2007; Dipeolu et al., Citation2009; Govindasamy et al., Citation2006; Obayelu et al., Citation2014; Owusu & Owusu Anifori, Citation2013; Saphores et al., Citation2007) argued that consumers are willing to pay more for organic food to some extent.

However, Bhavsar et al. (Citation2018) highlighted that a few studies have reported willingness to pay premiums closer to zero and in some cases to be negative. Krystallis and Chryssohoidis (Citation2005) are of the view that consumption of organic food has not caught on with the general public due to relatively “higher prices,” “lack of availability,” “lack of awareness of the organic concept,” and uncertainty over the truthfulness of organic food claims. Pacanoski (Citation2009) argued that low per capital income of some consumers might also be a reason why some consumers are not willing to pay for organic food, but those with higher levels of disposable income will be more willing to pay for organic food.

4.2. Food safety

The rapid change in food consumption pattern is as a result of consumers’ concern about the dietary value of food and their health (Bhavsar et al., Citation2018). The concerns for health and the environment appear to be very strong reasons for consumers when purchasing organic food (Baudry et al., Citation2017; Srinieng & Thapa, Citation2018; Tsakiridou et al., Citation2008). The choice of food consumers purchase and consume is based on the assertion that organically produced food is healthier than conventionally produced ones (Bhavsar et al., Citation2018; Gomiero, Citation2018; Mie et al., Citation2017; Rizzo et al., Citation2020; Tomas-Barberan & Gil, Citation2008). Conventional system of food production is characterized by the use of heavy artificial fertilizers and pesticides which often leave residues in the edible portion of the crop (Bhavsar et al., Citation2018). Notwithstanding, consumers regard organic food produces to be healthier than conventional food produces because of the minimal levels of pesticide residues (Meemken & Qaim, Citation2018; Saba & Messina, Citation2003; Watson, Citation2012; Wier et al., Citation2008). In the same vein, consumers view it as a safer alternative since they believe consuming it lessens their chances of being exposed to illness related to pesticide residues (Bhavsar et al., Citation2018). Therefore, these health trepidations are addressed by organic farming and the employment of safer food processing techniques (Furnham, Citation2007; Petrie et al., Citation2001).

4.3. Consumer awareness and understanding about organic product

Taking into account the Earth Day of 1990, regarding the environment, stressed that it is the duty of every individual “for personal health” and collective effort “on eco-friendly quality and animal well-being” (Jolly, Citation1990; MacEachern, Citation1990). Personal duties comprise making knowledgeable consumer decisions. This, therefore, entails consumer understanding and awareness about competing produces, and eagerness to pay a price premium for the products (Orzan et al., Citation2018; Yiridoe et al., Citation2005). Knowing that organic produces are credence goods, consumers “unlike producers who are cognisant that their produces are organic” may not know whether a product is grown using organic or inorganic techniques, not even after repeated buying and consumption, except they are told so (Giannakas, Citation2002; Wang et al., Citation2017). Therefore, it is important to note that awareness and consumer understanding about organic foods is important in the decision-making of consumer purchase. The inability of a person to distinctly distinguish between two alternatives goods, a price premium on the organic produce can complicate and or affect a person’s purchasing decision in favour of the low-cost goods (Yiridoe et al., Citation2005).

Yiridoe et al. (Citation2005) highlighted that consumer awareness and understanding about organic produces propose that in respective of the general consumer awareness globally, consumers “at times within the same region” have different understandings about what is “organic.” For instance, the findings of Jolly et al. (Citation1989), in a study conducted among consumers in three California districts, observed that respondents associated organic product with chemical-free products, no growth regulators, no chemical pesticide, and no artificial fertilizer. Also, a survey, conducted by Lo and Matthews (Citation2002) among consumers in the United Kingdom, suggests that respondents identified organic products to entail non-use of growth hormones, not intensively grown, chemical free, and products produced from Mother Nature. Moreover, in the UK study, it was observed that there was no discrepancy in consumers’ comprehension of “organic” amongst “organic and non-organic” food purchasers. Lo and Matthews (Citation2002) further argued that the two parties involved (buyers of organic and non-organic produce) felt that non-organic produces as well contain no pesticides or use no artificial regulators and are naturally grown and healthful. On the other hand, Jolly et al. (Citation1989) observed a significant difference in how United States buyers and non-buyers ranked organic produce quality, compared to alternatives grown produces.

Typically, consumers tend to understand the basic production issues associated with organic farming, while many tend not to comprehend the difficulties and niceties of organic farming procedures, and the associated quality features and/or benefits delineated in . Studies that investigated the level of consumer awareness and knowledge about organic foods include Yiridoe et al. (Citation2005); Bonti-Ankomah and Yiridoe (Citation2006); Mhlophe (Citation2016); Muhammad et al. (Citation2016); Nandi et al. (Citation2016); Rock et al. (Citation2017). A critical analysis of these studies proposes that, generally, there is some consumer awareness about organic foods around the world. This awareness is high mostly in Western Europe, where the organic market is comparatively well developed, compared to other regions of the world. As a result, Hill and Lynchehaun (Citation2002) proposed a hypothesis in explaining why some studies (Hutchins & Greenhalgh, Citation1997; Wolf, Citation2002) revealed inconsistencies and or uncertainty with consumer’s comprehension of the organic notion. For instance, the findings by Wolf (Citation2002) among US consumers revealed that consumers ranked the characteristics associated with “organic lettuce” like eco-friendly as “somewhat desirable” or “very desirable,” while others rated the “certified organic label” as only “slightly desirable” or “somewhat desirable.” This inconsistency was also observed by Hutchins and Greenhalgh (Citation1997) among shoppers in the UK. Their findings revealed that one-third of the respondents were aware of current organic tags; however, some of the respondents still find it difficult to identify the “symbol or logo” of the organic standards governing body in the county. de Magistris and Gracia (Citation2012) argued that consumers recognize organic foods based on the organic logos or labels attached to the product. Thus, awareness and understanding about organic foods are critical in the consumer purchase decision. Consumer understanding and awareness in the organic food market will continue to be vital in two respects (Demeritt, Citation2002). Firstly, there is still a segment of the potential market that is not yet informed about organic foods (Demeritt, Citation2002). Demeritt (Citation2002) further argued that lack of knowledge and awareness was reported as the number one reason why consumers do not buy organic food in a study which was conducted in United States. A second aspect to the understanding and awareness riddle is the possibility that individuals who do not consider organic foods may have a general knowledge about them, but do not have sufficient facts to clearly distinguish the exceptional attributes of organic from conventionally grown alternatives (Demeritt, Citation2002).

Table 2. Summary of key findings from selected studies on organic consumer attitudes and preferred quality attributes.

The findings of Yiridoe et al. (Citation2005) revealed that understanding and awareness about organic foods can influence attitudes and perceptions about the product and, in the long run, buying decisions. Consumer’s awareness is a product characteristic exploration and recognition by consumers (Muhammad et al., Citation2016), with the organic product’s attributes, such as nutritive contents, whether the product is certified organic or not, locally produced or imported, country of origin, labelling information as well as the level of freshness of the product (Muhammad et al., Citation2016). Specific trademarks are likely to be considered by the consumers to have high-quality organic products and as such this consideration may affect a consumers’ decision-making about purchasing a specific variety of food products (Al-Taie et al., Citation2015). Therefore, consumer awareness on organic food has proved to have a great influence on organic food consumption as indicated by several authors in this review.

4.4. Consumer attitudes and perceptions regarding organic food

Attitude is a psychological construct, a mental and emotional entity that inheres in, or characterizes a person (Symeonaki et al., Citation2018). Consumer actions, regarding organic food stem from attitudes that, in turn, are associated with a complex set of thoughts, motivations, and experiences (Yiridoe et al., Citation2005). This perception may or may not be based upon awareness, understanding, and a feeling regarding the object. Therefore, attitude is based upon an individual’s valuation of any emotional object (Carvalho, Citation2017). Vago and David (Citation2012) argued that the valuation decisions are usually determined as a substance of awareness and are categorized into three main groups, namely; cognitive awareness, emotional awareness, and awareness regarding past conduct. Consumer demand is associated with the characteristics inherent in economic goods (Lancester, Citation1966). However, consumer perceptions about organic versus conventionally produced foods, therefore, attempt to determine what consumers think is true (Shafie & Rennie, Citation2012; Srinieng & Thapa, Citation2018). By contrast, consumer attitudes are likes and dislikes. That is, the negative or positive mind set regarding conventional or organic grown foods. The choice for a certain produce is centred on attitudes towards available substitutes (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975). As a result, if consumers are enquired to specify their choice for foods that are produced organically versus conventional ones, such respondents habitually compare their attitudes towards the techniques used in producing the goods, and or the produce attributes under concern, before affirming their choices (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975). Although certain attitudes are usually presumed to lead to specific behaviours, literature provides limited proof to support this notion (Goldman & Clancy, Citation1991; Hay, Citation1989). Goldman and Clancy (Citation1991) further argued that consumer attitudes work in different ways, for and against buying organic foods.

Saba and Messina (Citation2003), in a study of 947 subjects, assessed attitudes and beliefs towards organic fruit and vegetable consumption, which is the most consumed organic food group, and found out that majority of the respondents tended to have a positive attitude towards consuming organic fruits and vegetables. Research has found that organic food is perceived by consumers to be less harmful to the environs and healthier than conventionally grown food (Aschemann-Witzel et al., Citation2013; Lim et al., Citation2020; Tran, Citation2017). Beliefs and perceptions are highly personal ideas, because they reflect ideas about the objective state of the world (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975). Fishbein and Ajzen (Citation1975) further argued that such perceptions may or may not be true, but the individual who holds the perception thinks it is true. For example, given Lancester’s (Citation1966) idea that consumers demand bundles of product characteristics, perceptions about specific (desired) characteristics of organic food can influence a buyer’s choice. shows some of the key findings from selected studies on consumers’ attitudes and perceptions about organic foods. Generally, most studies report that consumers purchase organic foods because of a perception that such products are safer, healthier and more environment-friendly than conventional grown alternatives. While some studies reported health and food safety as the number one quality attribute considered by organic produce buyers (Blair, Citation2011; Bonti-Ankomah & Yiridoe, Citation2006; Naspetti & Zanoli, Citation2009; Röhr et al., Citation2005), followed by concern for the environment (Blair, Citation2011; Gregory, Citation2000), suggesting that such consumers might rank private or personal benefits higher than the social benefits of organic agriculture.

4.5. Consumer preference on organic food consumption

Consumer preference for organic food is centred on a general perception that organic products have more desirable characteristics than conventionally produced alternatives (Bonti-Ankomah & Yiridoe, Citation2006). Apart from food safety, health, and environment concerns, several other product characteristics, such as taste, appearance, nutritive value, freshness, colour and other sensory characteristics, influence consumer preference (Bourn & Prescott, Citation2002; Petrescu et al., Citation2020; Udomkun et al., Citation2018). These studies differ in several respects, making comparison across studies difficult. For instance, there is inconsistency in defining the concept of quality.

A number of studies (for instance, Aguirre & Tumlty, Citation2001; Almli et al., Citation2019; Hempel & Hamm, Citation2016; The Packer, Citation2001; Wolf, Citation2002; Yue & Tong, Citation2009) have investigated the effect of organic quality attributes and other characteristics on consumer preferences. However, empirical evidence supports a hypothesis that product quality characteristics affect consumers’ preferences for organic food, with the most important being: nutritive value; economic value; freshness; flavour/taste; ripeness; and general appearance “especially of fruits and vegetables.” For example, Wolf (Citation2002) reported that respondents in California rated fresh-tasting and fresh-looking grapes as the most desirable attributes. Other North American studies that ranked taste as the most important quality characteristics influencing consumer demand include The Packer (Citation2001) and Demeritt (Citation2002). However, The Packer (Citation2001) reported that about 87% of US respondents identified taste as the main factor considered in the purchase of fresh produce. On the other hand, surveys for other part of the world (Buzby & Skees, Citation1994; Jolly et al., Citation1989; Torjusen et al., Citation1999) reported that consumers ranked nutritional value and freshness higher than taste and other related quality characteristics. Therefore, suggesting that relative ranking of the attributes that consumers prefer differs depending on the actual product (Hack, Citation1993) and across regions.

It appears that among the existing organic consumers, preference for organically grown foods tends to be influenced more by product quality and other inherent product characteristics than price premium (Bonti-Ankomah & Yiridoe, Citation2006). Studies of (Corfe, Citation2018; Maynard-Moody, Citation2000; Øystein et al., Citation2001; O’Donovan & McCarthy, Citation2002; Rödiger & Hamm, Citation2015; Terlau & Hirsch, Citation2015; The Packer, Citation2001; Wang et al., Citation2019), for example, reported that price premium, lack of knowledge and product availability were the major reasons preventing non-buyers from purchasing organic food. Similarly, Demeritt (Citation2002) reported that the most important reason why US consumers did not purchase organic food was lack of knowledge or awareness. Demeritt (Citation2002) further added that about 59% of those who did not purchase organic products indicated they never really considered organic, while about 39% indicated that price was the main inhibiting factor. About 16% also reported that they did not purchase organic food due to limited availability.

5. Theoretical considerations on consumer willingness on organic food consumption: application of the theory of planned behaviour

A major theory that informs studies on consumer behaviour is the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991). The theory states that attitude toward behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control, together shapes an individual’s behavioural intentions and behaviours (Ajzen, Citation1991). Several studies (Arvola et al., Citation2008; Hustvedt & Dickson, Citation2009; Jang et al., Citation2012; Kalafatis et al., Citation1999; Sparks & Shepherd, Citation1992; Thøgersen & Ölander, Citation2006) have applied this theory or its components to study consumer purchasing behaviour in regard to organic foods. This study also uses this theory to examine consumer’s willingness in regard to organic food consumption and the components of this theory are elaborated as follows.

5.1. Attitude

According to Honkanen et al. (Citation2006), an individual’s attitude towards consuming a product is one of the most significant antecedents for predicting and elucidating consumers’ choices across products and services, including food products. Tormala and Rucker (Citation2018) describe an attitude as a psychological construct which denotes an individual’s willingness to act or respond in a certain way. It involves a relatively enduring evaluation of an object against alternatives, and is centred upon a person’s thoughts (cognition), belief (values), and emotions (affection) towards the object (Dossey & Keegan, Citation2008).

A number of studies (for instance, Aryal et al., Citation2009; Gil & Soler, Citation2006; Thøgersen & Ölander, Citation2006) have associated organic food consumption with behavioural attitudes such as health consciousness, environmental consciousness, trust of organic food claims and desirability of organic food attributes such as freshness, taste, and texture. Bephage (Citation2000) pointed out that a person who has strong health values is probable to accept the significance of exercise, maintain a healthy nutrition, desist from smoking and consume moderate amounts of liquor. Organic food is mostly viewed as more nutritious and safer than conventionally produced ones; health-conscious individuals are more probable to develop a positive attitude towards the health enhancing features of organic food (Michaelidou & Hassan, Citation2008).

In a study by First and Brozina (Citation2009), on the effect of cultural difference on organic food consumption amongst consumers in the Western European countries, found that while the effect of cultural facets varied among the consumers, all exclusively considered health as the main reason for consumption of organic food. Roitner-Schobesberger et al. (Citation2008) also found that health consciousness was the prime reason to purchase organic food in Thailand. Roitner-Schobesberger et al. (Citation2008) further argued that consumers purchase organic food due to their concern with residues from synthetic chemicals used in agriculture. On the other hand, environmental consciousness was found to be a key determinant in a study conducted by Honkanen et al. (Citation2006) on Norwegian consumers. Honkanen et al. (Citation2006) investigated the ethical motives in consumers’ choice of organic food and discovered that environmental and animal right issues had a strong impact over attitudes toward organic food. Honkanen et al. (Citation2006) concluded that, the more concerned consumers are about these issues, the more positive their attitudes will be and the more probable they will consume organic food.

Trust of organic food claims is a strong element that determines the intension to consume due to the credence nature of organic food (Ham et al., Citation2015; Nuttavuthisit & Thøgersen, Citation2017; Teng & Wang, Citation2015). Voon et al. (Citation2011) describe trust as confidence in ones’ expectations, where desirable conducts are viewed as certain, while undesirable conducts are removed from consideration. Therefore, it is viewed that consumers may rely on product labelling, advertisements as well as certifications as sign of trustworthiness of product claims (Voon et al., Citation2011). Voon et al. (Citation2011) further argued that the extent that these engender consumer trust will thus influence the intention to consume organic food. Perrini et al. (Citation2010) in their study found that Italian consumers were more probable to trust retailers of organic products if they believe the retailer is committed to respecting their rights and the environment. Therefore, a favourable attitude towards organic food is probable to strengthen a person’s intention to purchase or consume organic food. For example, Ahmad and Juhdi (Citation2008) noted that consumers will have a positive attitude regarding organic foods if only they believe that it is far better and healthier than the conventional ones. For that reason, the likelihoods for them to buy organic foods will be higher.

5.2. Subjective norms

The term subjective norm refers to the perceived social pressure to undertake or not to undertake behaviour (Ajzen & Driver, Citation1991; O’Neal, Citation2007). A person’s subjective norms reflect their beliefs about how others, who are important to them, would view them engaging in a particular behaviour (Voon et al., Citation2011). The theory of needs, as proposed by McClelland (Citation1987), suggests that individuals tend to perform a behaviour that is believed desirable by loved ones or referent group, due to their need for affiliation and group identification. Therefore, a person’s intention to consume organic foods are probable to be strengthened if they believe that their loved ones expect them to do so, or they wish to be recognized with other people who are consuming organic food (Chen, Citation2007).

5.3. Perceived behavioural control

Perceived behavioural control is a concern with an individual’s perceptions to the extent they are able to perform given behaviour (Ajzen, Citation2001). This perception is based on individual’s belief about the relative ease or difficulty in performing the behaviour and the extent to which performance is given (Ajzen, Citation2002). Where the performance of behaviour is believed to be comparatively easy and within the means of the person, the intention to perform the behaviour will be strengthened. The studies of Thompson and Thompson (Citation1996); Notani (Citation1997); Oh and Hsu (Citation2001) have related affordability as a subset of behavioural control, in influencing behavioural intention. Voon et al. (Citation2011) define affordability as the ability to bear the cost for particular goods without a serious harm to the capacity for action. In this vein, for consumers, affordability is closely associated with monetary costs and search (convenience). The findings of ACNielsen (Citation2005) revealed that higher monetary cost was perceived as the main obstacle to organic food consumption for one-third of respondents in Asia Pacific and over 40% of European and North American consumers as cited in the work Voon et al. (Citation2011). Also, limitations in supplies and distribution channels were seen as factors that increase the cost of sourcing for organic food.

This can vary across different circumstances. As a result, a person can have a changing perception of behavioural control depending on the situations. Perceived behavioural control has a motivational implication on behaviour through intentions (Kidwell & Jewell, Citation2010; Martinez & Lewis, Citation2016; Rosenthal, Citation2018; Sommer, Citation2011). This can be related to the consumer’s perception of personal control over what to buy and eat. As a result, it can influence the consumer’s intention on the purchase of organic foods. This covers the effect of external factors such as labelling, place, and time. The combination of these factors may influence the consumers’ judgement of risks and benefits when buying the organic foods (Chen, Citation2007). For example, if consumers perceived they can easily get the organic foods or can easily identify the organic foods labels, then the intention to purchase it will be higher (Leong & Ng, Citation2014).

6. Model concept of factors influencing willingness to consume organic food

The model suggests that human behaviour is guided by three kinds of thought, that is the behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs, and control beliefs. In their respective aggregates, it is assumed that behavioural beliefs produce a favourable or unfavourable attitude towards the behaviour; normative beliefs result in subjective norm, while control beliefs give rise to perceived behavioural control. The combination of these beliefs leads to the formation of a behavioural intention (Ajzen, Citation2002). Noar and Zimmerman (Citation2005) argued that perceived behavioural control is presumed to not only affect actual behaviour directly but also affect it indirectly through behavioural intention.

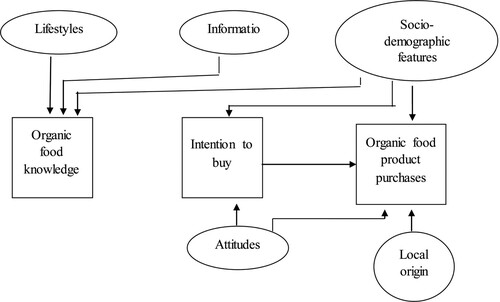

The more favourable the attitude toward behaviour and subjective norm, and the greater the perceived behavioural control, the stronger the person’s intention to perform the behaviour in question should be. Given a sufficient degree of actual control over behaviour, people are expected to carry out their intentions when the opportunity arises (Ajzen, Citation2002). Taking into account the principles stated by these three models, Gracia Royo and de Magistris (Citation2007) (), developed a model of consumer behaviour for organic foods relating to their willingness to consume organic food products.

7. Summary and conclusion

The rising interests in foods that are produced organically have prompted several studies comparing aspects of organic and conventional farming. This study reviewed several studies involving consumer willingness to consume organic food. A consumer-based approach to comprehend organic agriculture, involving such a comprehensive appraisal, is useful in helping not only for better understand changing organic market dynamics but also for organic consumer demand modelling and estimation, and market analysis. In general, consumer decision-making and behaviour towards organically produced products is consistent with an economic view that consumers demand the characteristics inherent in such products. The quality features of organic food constitute inputs into a consumer’s demand function for improved human health and general well-being.

Notwithstanding, the literature suggests some consumer understanding and awareness, however, consumer “sometimes within the same country” are not consistent in their interpretation of what is organic. Some doubt about the true attributes of organic and organic labels, part of which shoots from reported cases of mislabelling and product misrepresentation, and partly because of non-uniform organic standards, may hold some consumers back from purchasing organic products.

Food safety, human health, and environmental concern influence consumer preferences. Taking into account consumer preference for organic against conventional produced products is typically centred on a comparison of consumer attitudes towards the production systems used and product characteristics. Consumer preference for organic food is based on a general perception that such organic foods have more desirable features than its conventional counterparts. In general, consumers tend to prefer locally grown produce to shipments from other areas across the world. The effect of socio-economic and demographic variables (such as income) determines organic food purchases. Based on the studies reviewed some literature reported income as a barrier for organic purchasers, while income was not a barrier as reported in some literature. Empirical evidence of the relationship between particular organic foods and consumer income not only will help to better comprehend how consumers really perceive the quality and safety attributes of organic products compared to their conventional counterparts, but also have implications for organic products demand as average income levels increase with economic growth. The gradual increase in organic food production could also be seen in the global markets for certified organic products that have increased rapidly over the past decades. Most sales of the organic products are being generated in countries like North America and Europe, while regions like Asia, Latin America and Africa, are designated for exports.

Declaration of interest statement

There is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors express gratitude to the University of Fort Hare and also the Govan Mbeki Research and Development Centre of the University of Fort Hare for their support to develop this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- AC Nielsen. (2005). Organic and functional foods have plenty of room to grow according to new ACNielsen global study. Retrieved March 26, 2019 from http://enus.nielsen.com/content/nielsen/en_us/news.html

- Aertsens, J., Verbeke, W., Mondelaers, K., & Huylenbroeck, G. V. (2009). Personal determinants of organic food consumption: A review. British Food Journal, 111(10), 1140–1167. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700910992961

- Aguilar, F. X., & Vlosky, R. P. (2007). Consumer willingness to pay price premiums for environmentally certified wood products in the US. Forest Policy and Economics, 9(8), 1100–1112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2006.12.001

- Aguirre, G. J., & Tumlty, S. (2001). Marketing and consumption of organic products in Costa Rica (No. 5). Working Paper. The School for Field Studies, Centre for Sustainable Development.

- Ahmad, S. N. B., & Juhdi, N. (2008). Consumer’s perception and purchase intentions towards organic food products: Exploring the attitude among Malaysian consumers. In 16th Annual Conference on Pacific Basin Finance, Economics, Accounting and Management, Brisbane, Australia.

- Ahmed, S., & Stepp, J. R. (2016). Beyond yields: Climate effects on specialty crop quality and agroecological management. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 4, 92. https://doi.org/10.12952/journal.elementa.000092

- Aigner, A., Wilken, R., & Geisendorf, S. (2019). The effectiveness of promotional cues for organic products in the German retail market. Sustainability, 11(24), 6986. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246986

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2001). Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 27–58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.27

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x

- Ajzen, I., & Driver, B. L. (1991). Prediction of leisure participation from behavioral, normative, and control beliefs: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Leisure Sciences, 13(3), 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490409109513137

- Al-Taie, W. A., Rahal, M. K., AL-Sudani, A. S., & AL-Farsi, K. A. (2015). Exploring the consumption of organic foods in the United Arab Emirates. Sage Open, 5(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015592001

- Almli, V. L., Asioli, D., & Rocha, C. (2019). Organic consumer choices for nutrient labels on dried strawberries among different health attitude segments in Norway, Romania, and Turkey. Nutrients, 11(12), 2951. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122951

- Arvola, A., Vassallo, M., Dean, M., Lampila, P., Saba, A., Lähteenmäki, L., & Shepherd, R. (2008). Predicting intentions to purchase organic food: The role of affective and moral attitudes in the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite, 50(2-3), 443–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.09.010

- Aryal, K. P., Chaudhary, P., Pandit, S., & Sharma, G. (2009). Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic products: A case from Kathmandu valley. Journal of Agriculture and Environment, 10, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.3126/aej.v10i0.2126

- Aschemann-Witzel, J., Maroscheck, N., & Hamm, U. (2013). Are organic consumers preferring or avoiding foods with nutrition and health claims? Food Quality and Preference, 30(1), 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2013.04.011

- Baker, G. A., & Crosbie, P. J. (1993). Measuring food safety preferences: Identifying consumer segments. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 18, 277–287. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.30960

- Barański, M., Rempelos, L., Iversen, P. O., & Leifert, C. (2017). Effects of organic food consumption on human health; the jury is still out. Food and Nutrition Research, 61(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/16546628.2017.1287333

- Bartosz, G. (2013). Food oxidants and antioxidants: Chemical, biological, and functional properties. CRC Press.

- Baudry, J., Péneau, S., Allès, B., Touvier, M., Hercberg, S., Galan, P., Amiot, M. J., Lairon, D., Méjean, C., & Kesse-Guyot, E. (2017). Food choice motives when purchasing in organic and conventional consumer clusters: Focus on sustainable concerns (The NutriNet-Santé Cohort study). Nutrients, 9(2), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9020088

- Benbrook, C., Zhao, X., Yáñez, J., Davies, N., & Andrews, P. (2008). New evidence confirms the nutritional superiority of plant-based organic foods. In 136st APHA Annual Meeting and Exposition Conference. San Diego, California, 421–431

- Bephage, G. (2000). Social and behavioral sciences for nurses, an integrated approach. Churchill Livingstone Press.

- Bhavsar, H., Tegegne, F., Baryeh, K., & Illukpitiya, P. (2018). Attitudes and willingness to pay more for organic foods by Tennessee consumers. Journal Agricultural Science, 10(6), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v10n6p33

- Blair, R. (2011). Nutrition and feeding of organic cattle. CABI, Cambridge.

- Bonti-Ankomah, S., & Yiridoe, E. K. (2006). Organic and conventional food: A literature review of the economics of consumer perceptions and preferences. Organic Agriculture Centre of Canada, 59, 1–40.

- Bordeleau, G., Myers-Smith, I., Midak, M., & Szeremeta, A. (2002). Food quality: A comparison of organic and conventional fruits and vegetables. Kongelige Veterinoer-og Landbohøjskole.

- Bourn, D., & Prescott, J. (2002). A comparison of the nutritional value, sensory qualities, and food safety of organically and conventionally produced foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science & Nutrition, 42(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408690290825439

- Buzby, J. C., & Skees, J. (1994). Consumers want reduced exposure to pesticides in food. Food Review, 17(2), 19–22. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.266146

- Carvalho, L. C. (Ed.). (2017). Handbook of research on entrepreneurial development and innovation within smart cities. IGI Global.

- Caswell, J. A. (2002). Valuing the benefits and costs of improved food safety and nutrition. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 42(4), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8489.00060

- Chander, M., Bodapati, S., Mukherjee, R., & Kumar, S. (2011). Organic livestock production: An emerging opportunity with new challenges for producers in tropical countries. Revue Scientifique et Technique International Office of Epizootics, 30(3), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.30.3.2092

- Chang, J. M., & Fang, T. J. (2007). Survival of Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium in iceberg lettuce and the antimicrobial effect of rice vinegar against E. coli O157: H7. Food Microbiology, 24(7-8), 745–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2007.03.005

- Chen, M. F. (2007). Consumer attitudes and purchase intentions in relation to organic foods in Taiwan: Moderating effects of food-related personality traits. Food Quality and Preference, 18(7), 1008–1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2007.04.004

- Clark, T. (2002). The Organic Center. (2002) American chemical society research at great lakes meeting shows more vitamin C in organic oranges than conventional oranges. Science Daily. Retrieved May 23, 2020 from www.sciencedaily.com-/releases/2002/06/020603071017.htm.

- Corfe, S. (2018). What are the barriers to eating healthily in the UK? Social Market Foundation.

- Crinnion, W. J. (2010). Organic foods contain higher levels of certain nutrients, lower levels of pesticides, and may provide health benefits for the consumer. Alternative Medicine Review, 15(1), 4–12.

- Custer, C. (2018). Vinegar can help home cooks battle bacteria on leafy greens. [Online] Retrieved December 19, 2020 from https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2018/04/vinegar-can-help-home-cooks-battle-bacteria-on-leafy-greens/

- Dangour, A. D., Dodhia, S. K., Hayter, A., Allen, E., Lock, K., & Uauy, R. (2009). Nutritional quality of organic foods: A systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 90(3), 680–685. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.28041

- Davies, A., Titterington, A. J., & Cochrane, C. (1995). Who buys organic food? A profile of the purchasers of organic in Northern Ireland. British Food Journal, 97(10), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070709510104303

- Davis, J. G., & Kendal, P. (2005). Preventing E. coli from garden to plate. Food Safety, 9(369), 1–4.

- de Magistris, T., & Gracia, A. ( 2012). Do consumers pay attention to the organic label when shopping organic food in Italy?. In Matthew Reed Organic food and agriculture-new trends and developments in the social sciences (pp. 1–23). Intech.

- Demeritt, L. (2002). All things organic 2002: A look at the organic consumer. The Hartman Group.

- Denver, S., & Christensen, T. (2015). Organic food and health concerns: A dietary approach using observed data. NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 74, 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2015.05.001

- Dipeolu, A. O., Philip, B. B., Aiyelaagbe, I. O. O., Akinbode, S. O., & Adedokun, T. A. (2009). Consumer awareness and willingness to pay for organic vegetables in SW Nigeria. Asian Journal of Food and Agro-Industry, 10(11), 57–65.

- Domagała-Świątkiewicz, I., & Gąstoł, M. (2012). Comparative study on mineral content of organic and conventional carrot, celery and red beet juices. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Hortorum Cultus, 11(2), 173–183.

- Dossey, B., & Keegan, L. (2008). Holistic nursing: A handbook for practice. Jones and Bartlett Publishing.

- Ekelund, L. (1990). Vegetable consumption and consumer attitudes towards organically grown vegetables – The case of Sweden. Acta Horticulturae, 259(259), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.1990.259.14

- Esch, J. R., Friend, J. R., & Kariuki, J. K. (2010). Determination of the vitamin C content of conventionally and organically grown fruits by cyclic voltammetry. International Journal of Electrochemical Science, 5(1), 1464.

- First, I., & Brozina, S. (2009). Cultural influences on motives for organic food consumption. EuroMed Journal of Business, 4(2), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/14502190910976538

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Wiley and Sons.

- Frison, E. A. (2016). From uniformity to diversity: A paradigm shift from industrial agriculture to diversified agro-ecological systems. In International panel of experts on sustainable food systems (IPES) (pp. 96).

- Furnham, A. (2007). Are modern health worries, personality and attitudes to science associated with the use of complementary and alternative medicine? British Journal of Health Psychology, 12(2), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910706X100593

- Gastoł, M., & Domagała-Świątkiewicz, I. (2012). Comparative study on mineral content of organic and conventional apple, pear and black currant juices. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Hortorum Cultus, 11(3), 3–14.

- Giannakas, K. (2002). Information asymmetries and consumption decisions in organic food product markets. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 50(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7976.2002.tb00380.x

- Gil, J. M., & Soler, F. (2006). Knowledge and willingness to pay for organic food in Spain: Evidence from experimental auctions. Food Economics, 3(4), 109–124.

- Goldman, B. J., & Clancy, K. L. (1991). A survey of organic produce purchases and related attitudes of food cooperative shoppers. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 6(2), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0889189300003933

- Gomiero, T. (2018). Food quality assessment in organic vs. conventional agricultural produce: Findings and issues. Applied Soil Ecology, 123, 714–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.10.014

- Govindasamy, R., DeCongelio, M., & Bhuyan, S. (2006). An evaluation of consumer willingness to pay for organic produce in the north eastern US. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 11(4), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1300/J038v11n04_02

- Gracia Royo, A., & de-Magistris, T. (2007). Organic food product purchase behaviour: A pilot study for urban consumers in the South of Italy. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research, 5(4), 439–451. https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2007054-5356

- Greene, C., Ferreira, G., Carlson, A., Cooke, B., & Hitaj, C. (2017). Growing organic demand provides high-value opportunities for many types of producers. Amber Waves, p. 1. Retrieved May 24, 2020 from https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2017/januaryfebruary/growing-organic-demand-provides-high-value-opportunities-for-many-types-of-producers/

- Gregory, N. G. (2000). Consumer concerns about food. Outlook on Agriculture, 29(4), 251–257. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000000101293310

- Grunert, S. C., & Juhl, H. J. (1995). Values, environmental attitudes and buying of organic foods. Journal of Economic Psychology, 16(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4870(94)00034-8

- Grzybowska-Brzezinska, M., Grzywinska-Rapca, M., Zuchowski, I., & Bórawski, P. (2017). Organic food attributes determining consumer choices. European Research Studies Journal, 20(2A), 164–176. https://doi.org/10.35808/ersj/635

- Gumber, G., & Rana, J. (2017). Factors influencing willingness to pay price premium for organic food in India. Journal of International Food and Agribusiness Marketing, 32(1), 1–18.

- Hack, M. D. (1993). Organically grown products: Perception, preferences and motives of Dutch consumers. Acta Horticulturae, 340, 247–253. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.1995.340.32

- Ham, M., Pap, A., & Štimac, H. (2015). Eco-food production and market perspectives in Croatia. Business Logistics in Modern Management, 15, 93–109.

- Hamzaoui-Essoussi, L., & Zahaf, M. (2012). Production and distribution of organic foods: Assessing the added values. Organic Farming and Food Production, 145. https://doi.org/10.5772/52445

- Harper, G. C., & Makatouni, A. (2002). Consumer perception of organic food production and farm animal welfare. British Food Journal, 104(3-5), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700210425723

- Hay, J. (1989). The consumer’s perspective on organic foods. Canadian Institute of Food Science and Technology Journal, 22(2), 95–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0315-5463(89)70322-9

- Hempel, C., & Hamm, U. (2016). Local and/or organic: A study on consumer preferences for organic food and food from different origins. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(6), 732–741. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12288

- Hill, H., & Lynchehaun, F. (2002). Organic milk: Attitudes and consumption patterns. British Food Journal, 104(7), 526–542. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700210434570

- Honkanen, P., Verplanken, B., & Olsen, S. O. (2006). Ethical values and motives driving organic food choice. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 5(5), 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.190

- Hornick, S. B. (2010). Nutritional quality of crops as affected by management practices. Agricultural Research Service US Department of Agriculture (pp. 1–8). Beltsville, USA.

- Huang, C. L. (1996). Consumer preferences and attitudes towards organically grown produce. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 23(3–4), 331–342. https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/23.3.331

- Hughner, R. S., McDonagh, P., Prothero, A., Shultz, C. J., & Stanton, J. (2007). Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review, 6(2–3), 94–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.210

- Hurtado-Barroso, S., Tresserra-Rimbau, A., Vallverdú-Queralt, A., & Lamuela-Raventós, R. M. (2019). Organic food and the impact on human health. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 59(4), 704–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2017.1394815

- Hustvedt, G., & Dickson, M. A. (2009). Consumer likelihood of purchasing organic cotton apparel: Influence of attitudes and self-identity. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 13(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612020910939879

- Hutchins, R. K., & Greenhalgh, L. A. (1997). Organic confusion: Sustaining competitive advantage. British Food Journal, 99(9), 336–338. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070709710193998

- Ingham, S. C., Losinski, J. A., Andrews, M. P., Breuer, J. E., Breuer, J. R., Wood, T. M., & Wright, T. H. (2004). Escherichia coli contamination of vegetables grown in soils fertilized with non-composted bovine manure: Garden-scale studies. Applied Environmental Microbiology, 70(11), 6420–6427. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.70.11.6420-6427.2004

- James, J. (2006). Microbial hazard identification in fresh fruits and vegetables. John Wiley and Sons.

- Jang, J., Ko, E., Chun, E., & Lee, E. (2012). A study of a social content model for sustainable development in the fast fashion industry. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 3(2), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2012.10593108

- Johannessen, G. S., Bengtsson, G. B., Heier, B. T., Bredholt, S., Wasteson, Y., & Rørvik, L. M. (2005). Potential uptake of Escherichia coli O157: H7 from organic manure into crisphead lettuce. Applied Environmental Microbiology, 71(5), 2221–2225. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.5.2221-2225.2005

- Johansson, E., Hussain, A., Kuktaite, R., Andersson, S. C., & Olsson, M. E. (2014). Contribution of organically grown crops to human health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(4), 3870–3893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110403870

- Jolly, D. A. (1990). Determinants of organic horticultural products consumption based on a sample of California consumers. Horticultural Economics and Marketing, 295, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.1991.295.18

- Jolly, D. A., & Norris, K. (1991). Marketing prospects for organic and pesticide-free produce. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 6(4), 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0889189300004227

- Jolly, D. A., Schutz, H. G., Diaz-Knauf, K. V., & Johal, J. (1989). Organic foods: Consumer attitudes and use. Food Technology (Chicago), 43(11), 60–66.

- Kalafatis, S. P., Pollard, M., East, R., & Tsogas, M. H. (1999). Green marketing and Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour: A cross-market examination. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 16(5), 441–460. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363769910289550

- Kidwell, B., & Jewell, R. D. (2010). The motivational impact of perceived control on behavioral intentions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(9), 2407–2433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00664.x

- Krystallis, A., & Chryssohoidis, G. (2005). Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic food. British Food Journal, 1075(5), 320–343. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700510596901

- Kyriakopoulos, K., & Oude-Ophuis, A. M. (1997). A pre purchase model of consumer choice of biological foodstuff. Journal of International Food and Agribusiness Marketing, 8(4), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1300/J047v08n04_02

- Lairon, D. (2011). Nutritional quality and safety of organic food. A review. Médecine and Nutrition, 47(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1051/agro/2009019

- Lancester, K. J. (1966). A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy, 74(2), 132–157. Retrieved January 11, 2019 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1828835. https://doi.org/10.1086/259131

- Leong, G. Y., & Ng, Y. L.. (2014). Dissertation. Malaysia: University of Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR) http://eprints.utar.edu.my/1346/1/Consumption_of_Organic_Product.pdf

- Lester, G. E., & Saftner, R. A. (2011). Organically versus conventionally grown produce: Common production inputs, nutritional quality, and nitrogen delivery between the two systems. Journal of Agricultural & Food Chemistry, 59(19), 10401–10406. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf202385x

- Lim, S. A. H., Priyono, A., & Ming, C. H. (2020). An exploratory study of integrated management system on food safety and organic certifications. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(3), 882–892. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i3/7111

- Lin, B. H., Payson, S., & Wertz, J. (1996). Opinions of professional buyers toward organic produce: A case study of mid-Atlantic market for fresh tomatoes. Agribusiness: An International Journal, 12(1), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6297(199601/02)12:1<89::AID-AGR8>3.0.CO;2-L

- Lo, M., & Matthews, D. (2002). Results of routine testing of organic food for agro-chemical residues. Proceedings of the UK organic research 2002 Conference (pp. 26-28 March 2002.61–64). Organic Centre Wales, Institute of Rural Studies, University of Wales Aberystwyth.

- Lombardi-Boccia, G., Lucarini, M., Lanzi, S., Aguzzi, A., & Cappelloni, M. (2004). Nutrients and antioxidant molecules in yellow plums (Prunus domestica L.) from conventional and organic productions: A comparative study. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 52(1), 90–94. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf0344690

- Lusk, J. L., & Hudson, D. (2004). Willingness-to-pay estimates and their relevance to agribusiness decision making. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 26(2), 152–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9353.2004.00168.x

- MacEachern, D. (1990). Save our planet–750 everyday ways you can help clean up the Earth. Dell Publishing Group.

- Machado, D. C., Maia, C. M., Carvalho, I. D., Silva, N. F. D., André, M. C. D. P. B., & Serafini, ÁB. (2006). Microbiological quality of organic vegetables produced in soil treated with different types of manure and mineral fertilizer. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, 37(4), 538–544. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-83822006000400025

- Maffei, D. F., Batalha, E. Y., Landgraf, M., Schaffner, D. W., & Franco, B. D. (2016). Microbiology of organic and conventionally grown fresh produce. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, 47, 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjm.2016.10.006

- Magnusson, M.. (2004). Consumer perception of organic and genetically modified foods: Health and environmental considerations (Doctoral dissertation), Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Sweden. urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-4218

- Magnusson, M. K., Arvola, A., Hursti, U. K. K., Åberg, L., & Sjödén, P. O. (2003). Choice of organic foods is related to perceived consequences for human health and to environmentally friendly behaviour. Appetite, 40(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00002-3

- Marian, L., Chrysochou, P., Krystallis, A., & Thøgersen, J. (2014). The role of price as a product attribute in the organic food context: An exploration based on actual purchase data. Food Quality and Preference, 37, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.05.001

- Martinez, L. S., & Lewis, N. (2016). The moderated influence of perceived behavioral control on intentions among the general US population: Implications for public communication campaigns. Journal of Health Communication, 21(9), 1006–1015. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1204378

- Maynard-Moody, S. (2000). Demands for local and organic produce: A brief review of the literature. University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas, 1-57. Retrieved May 25, 2020 from http://ipsr.ku.edu/resrep/pdf/m254A.pdf

- McClelland, D. C. (1987). Human motivation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Meemken, E. M., & Qaim, M. (2018). Organic agriculture, food security, and the environment. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 10(1), 39–63. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100517-023252

- Melovic, B., Cirovic, D., Dudic, B., Vulic, T. B., & Gregus, M. (2020). The analysis of marketing factors influencing consumers’ preferences and acceptance of organic food products – Recommendations for the optimization of the offer in a developing market. Foods, 9(3), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9030259

- Merlini, V. V., Pena, F. D. L., da Cunha, D. T., de Oliveira, J. M., Rostagno, M. A., & Antunes, A. E. C. (2018). Microbiological quality of organic and conventional leafy vegetables. Journal of Food Quality, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4908316

- Mhlophe, B. (2016). Consumer purchase intentions towards organic food: Insights from South Africa. Business & Social Sciences Journal, 1(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.26831/BSSJ.2016.1.1.1-32

- Michaelidou, N., & Hassan, L. M. (2008). The role of health consciousness, food safety concern and ethical identity on attitudes and intentions towards organic food. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32(2), 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2007.00619.x

- Mie, A., Andersen, H. R., Gunnarsson, S., Kahl, J., Kesse-Guyot, E., Rembiałkowska, E., Quaglio, G., & Grandjean, P. (2017). Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture: A comprehensive review. Environmental Health, 16(1), 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0315-4

- Morshedi, L., Lashgarara, F., Farajollah Hosseini, S. J., & Omidi Najafabadi, M. (2017). The role of organic farming for improving food security from the perspective of Fars farmers. Sustainability, 9(11), 2086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112086

- Muhammad, S., Fathelrahman, E., & Tasbih Ullah, R. U. (2016). The significance of consumer’s awareness about organic food products in the United Arab Emirates. Sustainability, 8(9), 833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090833

- Nagy-Pércsi, K., & Fogarassy, C. (2019). Important influencing and decision factors in organic food purchasing in Hungary. Sustainability, 11(21), 6075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216075

- Nandi, R., Bokelmann, W., Gowdru, N. V., & Dias, G. (2016). Consumer motives and purchase preferences for organic food products: Empirical evidence from a consumer survey in Bangalore. South India. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 28(1), 74–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974438.2015.1035470

- Naspetti, S., & Zanoli, R. (2009). Organic food quality and safety perception throughout Europe. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 15(3), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454440902908019

- Nguyen, H. V., Nguyen, N., Nguyen, B. K., Lobo, A., & Vu, P. A. (2019). Organic food purchases in an emerging market: The influence of consumers’ personal factors and green marketing practices of food stores. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16061037

- Niggli, U., Slabe, A., Schmid, O., Halberg, N., & Schlüter, M. (2008). Vision for an organic food and farming research agenda 2025. Organic Knowledge for the Future (pp. 1–45). Retrieved May 22, 2020 from https://orgprints.org/13439/1/niggli-etal-2008-technology-platform-organics.pdf.

- Noar, S. M., & Zimmerman, R. S. (2005). Health behavior theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviors: Are we moving in the right direction? Health Education Research, 20(3), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyg113

- Notani, A. S. (1997). Perceptions of affordability: Their role in predicting purchase intent and purchase. Journal of Economic Psychology, 18(5), 525–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(97)00022-6

- Nuttavuthisit, K., & Thøgersen, J. (2017). The importance of consumer trust for the emergence of a market for green products: The case of organic food. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(2), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2690-5

- Obayelu, O. A., Agboyinu, O. M., & Awotide, B. A. (2014). Consumers’ perception and willingness to pay for organic leafy vegetables in urban Oyo State, Nigeria. European Journal of Nutrition & Food Safety, 127–136. https://doi.org/10.9734/EJNFS/2014/6498

- O’Donovan, P., & McCarthy, M. (2002). Irish consumer preference for organic meat. British Food Journal, 104(3-5), 353–370. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700210425778

- Oh, H., & Hsu, C. H. (2001). Volitional degrees of gambling behaviors. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(3), 618–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00066-9

- O’Neal, P. W. (2007). Motivation of health behavior. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

- Onyango, B. M., Hallman, W. K., & Bellows, A. C. (2007). Purchasing organic food in US food systems: A study of attitudes and practice. British Food Journal, 109(5), 399–411. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700710746803

- Orzan, G., Cruceru, A. F., Bălăceanu, C. T., & Chivu, R. G. (2018). Consumers’ behavior concerning sustainable packaging: An exploratory study on Romanian consumers. Sustainability, 10(6), 1787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061787

- Owusu, V., & Owusu Anifori, M. (2013). Consumer willingness to pay a premium for organic fruit and vegetable in Ghana. International Food & Agribusiness Management Review, 16, 67–86. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.144649

- Øystein, S., Persillet, V., & Sylvander, B. (2001). The consumers’ faithfulness and competence in regard to organic products: Comparison between France and Norway. Paper presented at the 2002 IFOAM Conference, Vancouver, Canada.

- Pacanoski, Z. (2009). The myth of organic agriculture. Plant Protection Science, 45(2), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.17221/43/2008-PPS

- The Packer. (2001). Fresh trends 2001: Understanding consumers and produce. Produce Marketing Association Fresh Summit 2000 Workshop Summary. Retrieved May 20, 2020 from http://www.pma.com

- The Packer. (2002). Fresh trends 2002: Key findings of Packer’s fresh trends report. Retrieved May 19, 2020 from http://www.bountyfresh.com/fresh_report4.htm

- Palupi, E., Jayanegara, A., Ploeger, A., & Kahl, J. (2012). Comparison of nutritional quality between conventional and organic dairy products: A meta-analysis. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 92(14), 2774–2781. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.5639

- Park, S., Navratil, S., Gregory, A., Bauer, A., Srinath, I., Jun, M., Szonyi, B., Nightingale, K., Anciso, J., & Ivanek, R. (2013). Generic Escherichia coli contamination of spinach at the preharvest stage: Effects of farm management and environmental factors. Applied Environmental Microbiology, 79(14), 4347–4358. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00474-13

- Paul, J., & Rana, J. (2012). Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(6), 412–422. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761211259223

- Pawlewicz, A. (2020). Change of price premiums trend for organic food products: The example of the Polish egg market. Agriculture, 10(2), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10020035

- Perrini, F., Castaldo, S., Misani, N., & Tencati, A. (2010). The impact of corporate social responsibility associations on trust in organic products marketed by mainstream retailers: A study of Italian consumers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 19(8), 512–526. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.660