Abstract

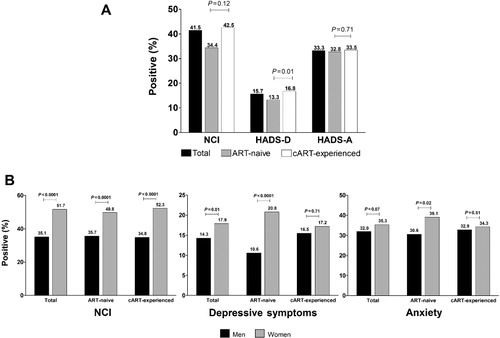

CRANIum, a cross-sectional epidemiology study in Western Europe and Canada, was conducted to describe and compare the prevalence of a positive screen for neurocognitive impairment (NCI), depressive symptoms, and anxiety in an HIV-positive population either receiving combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) or who were naive to antiretroviral therapy (ART). HIV-positive patients ≥18 years of age attending a routine medical follow-up visit and able to complete the designated screening tools were eligible for study inclusion. The Brief Neurocognitive Screen was used to assess NCI; depressive and anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. The evaluable patient population (N = 2863) included 1766 men (61.7%) and 1096 (38.3%) women. A total of 1969 patients were cART-experienced (68.8%), and 894 were ART-naive (31.2%). A positive screen for NCI was found in 41.5% of patients (cART-experienced, 42.5%; ART-naive, 39.4%; p = 0.12). A positive screen for depressive symptoms was found in 15.7% of patients (cART-experienced, 16.8%; ART-naive, 13.3%; p = 0.01), whereas 33.3% of patients screened positive for anxiety (cART-experienced, 33.5%; ART-naive, 32.8%; p = 0.71). A greater percentage of women compared with men screened positive for NCI (51.78% vs. 35.1%; p < 0.0001) and depressive symptoms (17.9% vs. 14.3%; p = 0.01). These data suggest that neurocognitive and mood disorders remain highly prevalent in HIV-infected patients. Regular mental health screening in this population is warranted.

Introduction

Infection with HIV is often preceded or accompanied by neuropsychiatric conditions including mood and personality disorders and psychosis (Bennett, Joesch, Mazur, & Roy-Byrne, Citation2009; Gaynes, Pence, Eron, & Miller, Citation2008; Owe-Larsson, Sall, Salamon, & Allgulander, Citation2009). Depression is the most prevalent psychiatric disorder among patients infected with HIV with a prevalence up to four times that of the general population (Bing et al., Citation2001). Suicides and anxiety disorders are more common among patients with HIV than uninfected individuals (Hinkin, Castellon, Atkinson, & Goodkin, Citation2001; Keiser et al., Citation2010; Sewell et al., Citation2000). In addition, neurocognitive impairment (NCI) is often associated with HIV infection (Chan, Kandiah, & Chua, Citation2012; Heaton et al., Citation2010; Lawler et al., Citation2011; Robertson et al., Citation2007). These disorders may affect quality of life and can contribute to increased morbidity and mortality (Andrinopoulos et al., Citation2011; Bing et al., Citation2000; Charles et al., Citation2012; Grov, Golub, Parsons, Brennan, & Karpiak, Citation2010; Hessol et al., Citation2007; Ickovics et al., Citation2001; Li, Lee, Thammawijaya, Jiraphongsa, & Rotheram-Borus, Citation2009; Reis et al., Citation2011; Tozzi et al., Citation2004; Wilkie et al., Citation1998; Wisniewski et al., Citation2005). A recently described meta-analysis found that the treatment of depression among HIV-infected individuals led to increases in antiretroviral adherence (Sin & DiMatteo, Citation2014).

This study was conducted to describe and compare the prevalence of a positive screening for NCI, anxiety, and/or depressive symptoms in an HIV-positive population receiving combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) versus antiretroviral therapy-naive (ART-naive) patients, and to explore potential associations between prevalence and sociodemographic and HIV disease characteristics.

Methods

Study design

CRANIum (sCReen for Anxiety, depression, and Neurocognitive Impairment in HIV+ patients) was a multinational, multicenter, cross-sectional epidemiology study, conducted among patients with HIV in Western Europe and Canada from October 2010 to June 2011. The study aimed to include ART-naive patients and patients treated with ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in a 1:1:1 ratio. An a-priori recruitment target of 40% female subjects was set for the overall study population. The primary objective of the study was to describe and compare the prevalence of a positive screen for NCI, depression, and anxiety in an HIV-infected population either receiving or naive to cART.

Study population

Patients were eligible for enrollment if they were infected with HIV, ≥18 years of age, attending a routine medical follow-up visit, and able to complete the designated screening tools. Patients receiving cART were required to be on their current antiretroviral regimen for ≥9 months. Exclusion criteria included a current or active opportunistic infection or malignancy of the central nervous system (CNS) and alcohol (>5 units/day) or illicit substance abuse within the previous three months. The study protocol was approved by the appropriate institutional review boards or independent ethics committees. Approved informed consent was obtained from subjects before enrollment.

Variables and instruments

NCI was assessed by the Brief Neurocognitive Screen (BNCS), a validated, but limited, screening (not diagnostic) tool (Ellis et al., Citation2005; Reitan & Wolfson, Citation1985; Wechsler, Citation1981). A positive screen for NCI per individual patient was defined as a z-score of one standard deviation below the mean on two tests or two standard deviations below the mean on one test (Heaton, Miller, Taylor, & Grant, Citation2004). Depressive and anxiety symptomatology were assessed using the self-administered Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire, which consists of seven items each relating to depression (HADS-D) and anxiety (HADS-A), respectively. A score of ≥8 on the HADS-D and HADS-A subscales (Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983) was considered a positive screen.

Statistical analysis

A total of 2575 patients was determined to provide 80% power to detect a difference in prevalence of 20–25% between treatment groups at a 5% significance level. (See online Supplementary Text 1 for additional statistical details.)

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 2884 patients from 15 countries in Western Europe and Canada were enrolled. The evaluable patient population (n = 2863) included 1766 men (61.7%) and 1096 women (38.3%; see online Supplementary Figure 1 for patient disposition). Demographic characteristics of patients are described in . The mean age of patients was 42.9 years (range, 19–83). Most patients were male (n = 1766 [61.7%] and white (n = 2256 [78.8%]), with a median HIV-1 RNA level of 633.5 copies/mL and a mean CD4+ T-cell nadir of 295 cells/µL.

Table 1. Demographic data and disease characteristics.

Neurocognitive impairment

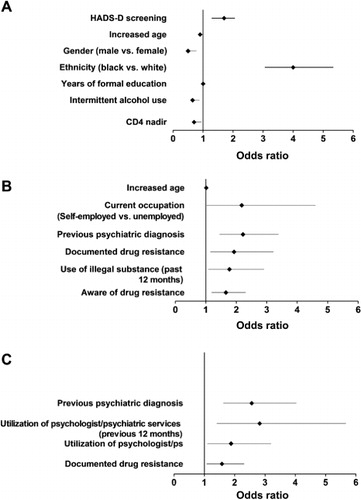

Among the evaluable patients, 41.5% screened positive for NCI. Of the ART-naive patients, 39.4% (352/894) screened positive for NCI, whereas 42.5% of cART-experienced patients (836/1969) screened positive for NCI (p = 0.12; ). Factors associated with NCI are shown in .

Depression and anxiety

Among the evaluable patients, 15.7% screened positive for depression and 33.3% screened positive for anxiety (). A significantly greater percentage of cART-experienced patients (326/1941 [16.8%]) screened positive for depression compared with ART-naive patients (117/882 [13.3%]; p = 0.01), whereas the percentage of patients screening positive for anxiety was similar between ART-naive (290/884 [32.8%]) and cART-experienced patients (648/1933 [33.5%]; p = 0.71). Factors associated with a positive screen for depressive symptoms and for anxiety are shown in and , respectively.

Gender analysis

Women comprised nearly 40% of the study population. The proportion of black patients was significantly higher among women than men (25.8% vs. 5.9%; p < 0.0001). A greater proportion of men completed secondary or higher education (87.3% vs. 73.7%; p < 0.0001). Men were more likely to smoke or to use alcohol or illegal substances. Women who were cART-experienced had a significantly lower CD4+ T-cell count nadir (203.4 cells/µL) than cART-experienced men (228.2 cells/µL; p = 0.0017). Additional demographic data based on gender can be found in the online Supplementary Table 1.

There was a significantly higher percentage of women with a positive screen for NCI compared with men (51.7% vs. 35.1%; p < 0.0001; ). This difference was consistent among the cART-experienced (52.3% women vs. 34.8% men; p < 0.0001) and ART-naive populations (49.8% women vs. 35.7% men; p < 0.0001). In patients with a negative screen for depression (HADS-D < 8, n = 2380), 48.5% of women versus 33.7% of men (p < 0.0001) had a positive screen for NCI.

A significantly greater percentage of women screened positive for depression (17.9%) compared with men (14.3%; p = 0.01), driven by differences observed in the ART-naive group (20.8% women; 10.6% men; p < 0.0001; ). Differences between genders for a positive screen for anxiety did not reach statistical significance overall (women 35.3%; men 32.0%; p = 0.07) but were significantly higher in the ART-naive group (39.1% women; 30.6% men; p = 0.02; ).

Discussion

In CRANIum, more than 40% of the patients infected with HIV screened positive for NCI, similar to the rate reported in an earlier study (Heaton et al., Citation2011). The prevalence of a positive screen for NCI was not statistically different between patients who were cART-experienced and ART-naive; however, differences in demographics and disease characteristics between the groups should be considered. Patients treated with cART who had a lower viral load (≤50 copies/mL) were less likely to screen positive for NCI. Gender subgroup analysis demonstrated that women were significantly more likely to screen positive for NCI than men, independent of receipt of cART. Although significant differences in demographic and HIV disease characteristics were found between genders (a greater proportion of women were black and unemployed, and fewer women had a secondary or higher education), female gender was identified as a risk factor in the multivariate analysis.

Approximately one-third of the patients in this study screened positive for anxiety, and approximately 16% screened positive for depressive symptomatology. The percentage of patients who screened positive for depressive symptoms in this study is approximately twice that previously reported for depression in the general European population (Ayuso-Mateos et al., Citation2001).

Compared with men, a higher proportion of women screened positive for depressive symptoms; however, significant differences in demographic and disease characteristics were found between the genders; being female was not an identified risk factor for a positive screen for depression in multivariate analysis. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among women infected with HIV in this study is nearly twice that reported for women in the general European population (Ayuso-Mateos et al., Citation2001). Previous studies have concluded that depression and depressive symptomatology seem more prevalent and severe in HIV-infected women compared with HIV-infected men (Kinyanda, Hoskins, Nakku, Nawaz, & Patel, Citation2011; Reis et al., Citation2011; Turner, Laine, Cosler, & Hauck, Citation2003). The high number and percentage of women included in this study (n = 1096, 38.3%) provide robust data.

Due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, the interpretation of predictive associations between risk factors and outcomes is difficult and does not demonstrate causality. Limitations of this study include the use of screening tools rather than structured or semistructured diagnostic interviews to diagnose depression and anxiety. Moreover, only three tests, and not a complete battery, were used to evaluate NCI. Additionally, this study used normalized data for the prevalence of neuropsychologic conditions from a US population; normative data from each of the countries that enrolled subjects in the study were not available, and the local differences in population risk may have an impact on the impairment assessed. Because the prevalence of NCI in the general population is most often provided for older adults, comparison of the population in this study (mean age 42.9 years) with an age-matched historical control is difficult.

Strengths of our study comprise both the large overall and female populations included. The subjects in this study were residents of a wide geographic area encompassing 15 countries, whereas most previous studies have tended to focus on individual countries (Chan et al., Citation2012; Gaynes et al., Citation2008; Kinyanda et al., Citation2011; Pappin, Wouters, & Booysen, Citation2012). Nonetheless, the rates of impairment observed in this study are comparable to those seen in other studies (Chan et al., Citation2012; Gaynes et al., Citation2008; Pappin et al., Citation2012).

Neuropsychological and psychiatric symptoms in the HIV population have obvious implications for treatment and serve as a reminder to health-care providers of the importance of comorbid mental health issues and neurocognitive functioning. Data in this study suggest that screenings for NCI, depression, and anxiety should be included in the routine clinical HIV management algorithms, especially for patients with identified risk factors.

Supplementary material

Supplementary (Figure 1/Table 1/content) is available via the ‘Supplementary’ tab on the article's online page (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2014.936813).

Supplementary_Material.rar

Download (488.6 KB)Acknowledgments

All the authors have participated in study design and/or acquisition of data and had full access to the study data and analyses, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. Statistical analyses were performed by Francesc Miras Rigol, RPS Research Iberica, Barcelona, Spain.

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in this study. Medical writing support was provided by Daniel McCallus, Ph.D., Complete Publication Solutions, LLC, Horsham, PA, USA; this support was funded by AbbVie. The authors would like to acknowledge the investigators who contributed to this study and their teams as listed in the Appendix.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: The design, study conduct, analysis, and financial support of the study were provided by AbbVie. AbbVie participated in the interpretation of data, review, and approval of the manuscript. Kevin Robertson has received consulting fees and/or honoraria from AbbVie, GlaxoSmithKline, and Viiv, and his institution has received grants from the National Institutes of Health. Carmen Bayon has received consulting fees and/or honoraria and support for travel from AbbVie, and has received payment for the development of educational presentations from AstraZeneca Spain. Jean-Michel Molina has received advisory board member fees, travel fees, and speaker fees from Merck, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Gilead, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and his institution has received grants from Merck Sharpe & Dohme. Patricia McNamara's institution has received grants from AbbVie. Christiane Resch has received travel fees from AbbVie unrelated to this manuscript. Jose A. Muñoz-Moreno has received grants, travel sponsorships, research support, speaking fees, or consultancy fees, and has served on advisory boards for AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Ranjababu Kulasegaram has received grants, travel sponsorship, research support, speaking fees, or consultancy fees and has served on advisory boards for ViiV, Merck Sharp & Dohme, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Gilead Sciences. Knud Schewe has received consultancy fees and/or speakers fees from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and ViiV Healthcare and has received travel expenses unrelated to this manuscript. Angel Burgos-Ramirez, Cristina De Alvaro, Esther Cabrero, Michael Norton, and Jean van Wyk are AbbVie employees and may hold stock or options in AbbVie. Matthew Guion is a former AbbVie employee and current Gilead Sciences employee and may hold stock or options in AbbVie.

References

- Andrinopoulos, K., Clum, G., Murphy, D. A., Harper, G., Perez, L., Xu, J., … Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV AIDS Interventions. (2011). Health related quality of life and psychosocial correlates among HIV-infected adolescent and young adult women in the US. AIDS Education and Prevention, 23, 367–381. doi:10.1521/aeap.2011.23.4.367

- Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Vazquez-Barquero, J. L., Dowrick, C., Lehtinen, V., Dalgard, O. S., Casey, P., … Odin Group. (2001). Depressive disorders in Europe: Prevalence figures from the ODIN study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 179, 308–316. doi:10.1192/bjp.179.4.308

- Bennett, W. R., Joesch, J. M., Mazur, M., & Roy-Byrne, P. (2009). Characteristics of HIV-positive patients treated in a psychiatric emergency department. Psychiatric Services, 60, 398–401. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.398

- Bing, E. G., Burnam, M. A., Longshore, D., Fleishman, J. A., Sherbourne, C. D., London, A. S., … Shapiro, M. (2001). Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus–infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 721–728. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721

- Bing, E. G., Hays, R. D., Jacobson, L. P., Chen, B., Gange, S. J., Kass, N. E., … Zucconi, S. L. (2000). Health-related quality of life among people with HIV disease: Results from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Quality of Life Research, 9(1), 55–63. doi:10.1023/A:1008919227665

- Chan, L. G., Kandiah, N., & Chua, A. (2012). HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) in a South Asian population - Contextual application of the 2007 criteria. BMJ Open, 2, e000662. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000662

- Charles, B., Jeyaseelan, L., Kumar Pandian, A., Edwin Sam, A., Thenmozhi, M., & Jayaseelan, V. (2012). Association between stigma, depression and quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) in South India – A community based cross sectional study. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 463. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-463

- Ellis, R. J., Evans, S. R., Clifford, D. B., Moo, L. R., McArthur, J. C., Collier, A. C., … AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study Teams A5001 and A362. (2005). Clinical validation of the NeuroScreen. Journal of Neurovirology, 11, 503–511. doi:10.1080/13550280500384966

- Gaynes, B. N., Pence, B. W., Eron, J. J., Jr., & Miller, W. C. (2008). Prevalence and comorbidity of psychiatric diagnoses based on reference standard in an HIV+ patient population. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70, 505–511. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816aa0cc

- Grov, C., Golub, S. A., Parsons, J. T., Brennan, M., & Karpiak, S. E. (2010). Loneliness and HIV-related stigma explain depression among older HIV-positive adults. AIDS Care, 22, 630–639. doi:10.1080/09540120903280901

- Heaton, R. K., Clifford, D. B., Franklin, D. R., Jr., Woods, S. P., Ake, C., Vaida, F., … CHARTER Group. (2010). HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology, 75, 2087–2096. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727

- Heaton, R. K., Franklin, D. R., Ellis, R. J., McCutchan, J. A., Letendre, S. L., Leblanc, S., … HNRC Group. (2011). HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: Differences in rates, nature, and predictors. Journal of Neurovirology, 17, 3–16. doi:10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1

- Heaton, R. K., Miller, S. W., Taylor, M. J., & Grant, I. (2004). Revised comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically adjusted neuropsychological norms for African American and Caucasian adults. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resouces.

- Hessol, N. A., Kalinowski, A., Benning, L., Mullen, J., Young, M., Palella, F., … Cohen, M. H. (2007). Mortality among participants in the multicenter AIDS cohort study and the women's interagency HIV study. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 44, 287–294. doi:10.1086/510488

- Hinkin, C. H., Castellon, S. A., Atkinson, J. H., & Goodkin, K. (2001). Neuropsychiatric aspects of HIV infection among older adults. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54, S44–S52. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00446-2

- Ickovics, J. R., Hamburger, M. E., Vlahov, D., Schoenbaum, E. E., Schuman, P., Boland, R. J., … HIV Epidemiology Research Study Group. (2001). Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: Longitudinal analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study. JAMA, 285, 1466–1474. doi:10.1001/jama.285.11.1466

- Keiser, O., Spoerri, A., Brinkhof, M. W., Hasse, B., Gayet-Ageron, A., Tissot, F., … Swiss National Cohort. (2010). Suicide in HIV-infected individuals and the general population in Switzerland, 1988–2008. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(2), 143–150. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050651

- Kinyanda, E., Hoskins, S., Nakku, J., Nawaz, S., & Patel, V. (2011). Prevalence and risk factors of major depressive disorder in HIV/AIDS as seen in semi-urban Entebbe district, Uganda. BMC Psychiatry, 11, 205. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-205

- Lawler, K., Jeremiah, K., Mosepele, M., Ratcliffe, S. J., Cherry, C., Seloilwe, E., & Steenhoff, A. P. (2011). Neurobehavioral effects in HIV-positive individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in Gaborone, Botswana. PLoS ONE, 6, e17233. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017233

- Li, L., Lee, S. J., Thammawijaya, P., Jiraphongsa, C., & Rotheram-Borus, M. J. (2009). Stigma, social support, and depression among people living with HIV in Thailand. AIDS Care, 21, 1007–1013. doi:10.1080/09540120802614358

- Owe-Larsson, B., Sall, L., Salamon, E., & Allgulander, C. (2009). HIV infection and psychiatric illness. African Journal of Psychiatry (Johannesbg), 12, 115–128.

- Pappin, M., Wouters, E., & Booysen, F. L. (2012). Anxiety and depression amongst patients enrolled in a public sector antiretroviral treatment programme in South Africa: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 12, 244. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-244

- Reis, R. K., Haas, V. J., Santos, C. B., Teles, S. A., Galvao, M. T., & Gir, E. (2011). Symptoms of depression and quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 19, 874–881. doi:10.1590/S0104-11692011000400004

- Reitan, R. M., & Wolfson, D. (1985). The Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological test battery. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press.

- Robertson, K. R., Smurzynski, M., Parsons, T. D., Wu, K., Bosch, R. J., Wu, J., … Ellis, R. J. (2007). The prevalence and incidence of neurocognitive impairment in the HAART era. AIDS, 21, 1915–1921. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e32828e4e27

- Sewell, M. C., Goggin, K. J., Rabkin, J. G., Ferrando, S. J., McElhiney, M. C., & Evans, S. (2000). Anxiety syndromes and symptoms among men with AIDS: A longitudinal controlled study. Psychosomatics, 41, 294–300. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.41.4.294

- Sin, N. L., & DiMatteo, M. R. (2014). Depression treatment enhances adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 47, 259–269. doi:10.1007/s12160-013-9559-6

- Tozzi, V., Balestra, P., Murri, R., Galgani, S., Bellagamba, R., Narciso, P., … Wu, A. W. (2004). Neurocognitive impairment influences quality of life in HIV-infected patients receiving HAART. International Journal of STD and AIDS, 15, 254–259. doi:10.1258/095646204773557794

- Turner, B. J., Laine, C., Cosler, L., & Hauck, W. W. (2003). Relationship of gender, depression, and health care delivery with antiretroviral adherence in HIV-infected drug users. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 18, 248–257. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20122.x

- Wechsler, D. (1981). Wechsler adult intelligence scale-revised manual. New York, NY: The Psychological Corporation.

- Wilkie, F. L., Goodkin, K., Eisdorfer, C., Feaster, D., Morgan, R., Fletcher, M. A., … Szapocznik, J. (1998). Mild cognitive impairment and risk of mortality in HIV-1 infection. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 10, 125–132.

- Wisniewski, A. B., Apel, S., Selnes, O. A., Nath, A., McArthur, J. C., & Dobs, A. S. (2005). Depressive symptoms, quality of life, and neuropsychological performance in HIV/AIDS: The impact of gender and injection drug use. Journal of Neurovirology, 11, 138–143. doi:10.1080/13550280590922748

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361–370. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Appendix

Austria: Dr. Vetter, Dr. Geit, Dr. Prammer; Belgium: Dr. Vandekerckhove, Prof. Moutschen, Prof. Vandercam; Canada: Dra. Loutfy, Dr. DeWet, Dr. Baril, Dr. Trottier, Dra. Walmsley, Dr. Gill; France: Dr. Bouchaud, Dr. De Truchis, Dr. Djerad, Dr. Gasnault, Dr. Gilquin, Dr. Hocqueloux, Dr. Hoen, Dra. Khuong, Dr. Lafeuillade, Dr. Le Moal, Dra. Leclercq, Dr. Molina, Dr. Patey, Dr. Pellegrin, Dr. Rogeaux, Dra. Salmon, Dr. Treilhou; Germany: Dr. Rockstroh, Dr. Schewe, Dr. Mayr, Dr. Pauli, Dr. Baumgarten, Dr. Lutz, Dr. Jäger, Dr. Knechten, Dr. Cordes; Greece: Dr. Gargalianos, Dra. Sabatakou, Dr. Katsabas, Dr. Skoutelis, Dr. Ploumidis; Ireland: Prof. Bergin, Dr. McNamara; Israel: Dr. Pollak, Dr. Elbirt, Dr. Maayan, Dr. Levy, Dr. Riesenberg; Italy: Dr. Antinori, Dr. Carosi, Dra. Mussini, Dr. Galli, Dra. Cinque, Dr. Parruti, Dr. Rizzardini, Dr. Viale; Norway: Dr. Leiva, Dr. Ringstad; Portugal: Dr. Serrão, Dr. Mansinho; Spain: Dr. Hernández-Quero, Dr. Colmenero, Dr. Terrón, Dr. Rodríguez-Baño, Dr. Lozano, Dr. de Zárraga, Dr. Llunch, Dr. Florez, Dra. Martínez, Dr. Rodriguez, Dra. Sepúlveda, Dr. Elizaga, Dr. Bahamonde, Dra. Garcínuño, Dr. Podzamczer, Dr. Mallolas, Dr. Clotet, Dr. Munoz, Dr. Domingo, Dr. Pedrol, Dr. Knobel, Dra. Omella, Dr. Aranda, Dr. Force, Dr. Barros, Dr. Martín, Dr. Arribas, Dr. Casado, Dr. Cuadrado, Dra. Oltra, Dr. Roca, Dr. Ortega, Dr. Fernández, Dr. Rodríguez, Dr. Morano, Dr. Canet, Dr. García-Henarejos, Dr. Cano, Dr. Goenaga, Dra. Muñoz, Dra. Goicoechea; Sweden: Prof. Nilsson Schönnesson, Dra. Schlaug, Dr. Flamholc, Dr. Bonnedahl, Dr. Briheim; Switzerland: Dr. Zimmerli, Dr. Vernazza, Dr. Cavassini; UK: Dr. Gompels, Prof. Lee, Dr. Price, Dr. Leen, Dr. Nelson, Prof. Johnson, Dr. Kulasegaram.