Abstract

Existing studies have delineated that HIV-infected parents face numerous challenges in disclosing their HIV infection to the children (“parental HIV disclosure”), and practices of parental HIV disclosure vary with individual characteristics, family contexts, and social environment. Using cross-sectional data from 1254 HIV-infected parents who had children aged 5–16 years in southwest China, the current study examined the association of parental HIV disclosure with mental health and medication adherence among parents and explored the possible effect of enacted stigma on such association. Multivariate analysis of variance revealed that parents who had experienced disclosure to children reported higher level enacted stigma, worse mental health conditions, and poorer medication adherence. Enacted stigma partially mediated the associations between disclosure and both mental health and medication adherence after controlling basic background characteristics. Our findings highlight the importance of providing appropriate disclosure-related training and counseling service among HIV-infected parents. In a social setting where HIV-related stigma is still persistent, disclosure intervention should address and reduce stigma and discrimination in the practice of parental HIV disclosure.

Introduction

Along with increasing accessibility of the antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV has been transforming from a rapidly fatal illness to a manageable chronic disease (Shacham, Small, Onen, Stamm, & Overton, Citation2012). As individuals with HIV infection are expected to live longer and be able to raise children many years after the initial diagnosis, there are a greater number of opportunities for HIV-infected parents to disclose the HIV serostatus to children (“parental disclosure”). A growing body of evidence has shown the potential benefits of parental disclosure on parents, children, and family. For instance, disclosure to children might be associated with parents’ better adherence to clinic appointment and medication, lower stress and depression, and higher social support (Qiao, Li, & Stanton, Citation2013); children who were disclosed by parents might suffer fewer negative long-term effects (Murphy, Marelich, & Hoffman, Citation2002); parental disclosure might also strengthen parent–child relationship and improve family cohesion (Tenzek, Herrman, May, Feinerd, & Allenb, Citation2013).

However, parents may face numerous challenges in disclosing their HIV infection to children. Parental HIV disclosure rate is still low, particularly in resources constrained settings (Qiao et al., Citation2013). Most of HIV-infected parents are confronted with difficulties regarding disclosure to children in terms of making decisions, conducting a disclosure, and dealing with children’s reactions. These difficulties may be attributed to their lack of accurate HIV knowledge, limited communication skills with children, concerns of children’s inability to understand HIV due to their early developmental stage, as well as poor parent–child relation and existing family conflicts and crisis (Clifford, Craig, McCourt, & Barrow, Citation2013). In addition to individual characteristics of parents and children and family relationship and environment, some societal level factors, such as HIV-related stigma, may also play an important role in the decision-making of parental HIV disclosure, shape the practice of disclosure, and affect the consequences of disclosure.

Stigma has been conceptualized as a discrediting and tainting social labeling process (Alonzo & Reynolds, Citation1995; Goffman, Citation1963), an extreme disapproval of an individual or group on socially characteristic grounds, which distinguishes them from other members of a society (Goffman, Citation1963). Individuals with the stigmatized attribute may be subjected to overt acts of hostility and discrimination (enacted stigma; Katz et al., Citation2013). Stigmatized persons may internalize the devaluation by the community and develop negative perceptions about themselves (internal stigma; Greeff et al., Citation2008). The HIV-related stigma has been adversely affecting HIV testing (Okoror, Belue, Zungu, Adam, & Airhihenbuwa, Citation2014), health seeking (Steward, Bharat, Ramakrishna, Heylen, & Ekstrand, Citation2013), and medication adherence (Katz et al., Citation2013) among HIV-infected people. It also encroaches on their psychosocial well-being (Sun, Wu, Qu, Lu, & Wang, Citation2014) and impedes their disclosing HIV status to others (Tsai et al., Citation2013). For example, HIV-related stigma and discrimination were reported as the main barrier of disclosing HIV infection to sexual partners and family members among people living with HIV (PLHIV; Shacham et al., Citation2012).

Existing literature on parental HIV disclosure have focused on the role of stigma in the decision-making process. Stigma has been reported as one of major barriers to parents’ disclosing to children (Clifford et al., Citation2013). According to empirical studies, main reasons for nondisclosure include fear of stigma and discrimination, fear of secondary disclosure (children disclose to others), feelings of shame and guilt, and fear of rejection or losing respect from children (Kyaddondo, Wanyenze, Kinsman, & Hardon, Citation2013; Lee, Li, Iamsirithaworn, & Khumtong, Citation2013; Qiao, Li, & Stanton, Citation2014). Almost all these reasons are linked to HIV-related stigma. Several studies on general HIV disclosure have outlined the effects of stigma on disclosure practices (Dima, Stutterheim, Lyimo, & de Bruin, Citation2014; Greeff et al., Citation2008; Sandelowski, Lambe, & Barroso, Citation2004). However, very few studies have investigated the possible role of enacted stigma in mediating the association between parental HIV disclosure and their mental health or medication adherence among HIV-infected parents.

Despite that the biomedical advances have transformed HIV into a chronic condition, HIV-related stigma and discrimination (e.g., enacted stigma) is evident and persistent in contemporary society, particularly in low- and middle-income countries including China (Grossman & Stangl, Citation2013). It is crucial to address the role of stigma in parental disclosure so we can develop more efficacious and practical strategies to assist HIV-infected parents to make appropriate decisions to disclose their HIV status to children. Using cross-sectional data from HIV-infected parents in southwest China, the current study aims to contribute empirical evidence to this issue by (1) reporting how parental HIV disclosure is associated with mental health (depression and anxiety) and ART adherence among the HIV-infected parents; (2) examining the possible role of enacted stigma in mediating the association of parental disclosure with mental health and ART adherence.

Method

Study site and participants

Data used in the current study were derived from a cross-sectional survey, which was conducted from October 2012 to August 2013 in Guangxi Autonomous Region (Guangxi) of China. Guangxi is ranked second at provincial level in terms of HIV prevalence and first in terms of newly reported HIV infection cases in China (Guangxi Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Citation2009). With the assistance and collaboration of Guangxi CDC, a total of 29,606 recorded HIV and AIDS cases (i.e., 43% of all reported cases in Guangxi at the end of 2011) was selected as the sampling frame from the 12 sites (2 cities and 10 counties) with the largest cumulative number of reported HIV and AIDS cases. The Project coordinator at each site was instructed to randomly recruit about 10% of its reported cases to participate in the survey. With an overall participation rate of 90%, a total of 3002 HIV patients participated in the survey and 2987 of them completed the survey. As the current study focused on parental HIV disclosure, a subsample of 1254 participants who had children aged 5–16 years was included in the data analysis.

Survey procedure

Participants completed an assessment inventory including demographic characteristics and HIV-related measures, HIV disclosure, mental health, and ART adherence. The survey was conducted in private offices of local CDC or HIV clinics where the participants received medical service. About 20% of the participants completed the questionnaire on their own. For the rest of the sample, the interviewers read the items to the participants and recorded the response on the questionnaire. The interviewers were local CDC staff or health-care workers in the HIV clinics who had received intensive training on research ethics and interview skills with PLHIV prior to the data collection. The survey protocol including consenting process was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Wayne State University in the USA and Guangxi CDC in China.

Measures

Background characteristics

Participants were asked about individual and family characteristics including gender, age, ethnicity, religion, marital status, place of original residence, education attainment, work status, number of people in the family, number of children, and monthly household income. Participants were also asked to provide HIV-related information, including duration since their HIV diagnosis, and HIV infection among other family members.

Parental HIV disclosure

The participants were asked to check all individuals “To whom you have told about your HIV status.” A positive response to “children under the age of 18” was considered as having conducted parental HIV disclosure. In addition, they were also asked “Did your children know about your HIV status?” For the purpose of data analysis in the current study, parents who gave positive response to either of the two questions were categorized into “disclosed group,” otherwise, they were in “no-disclosed group.”

Enacted stigma

The participants were asked about the frequency of encountering acts of discrimination against PLHIV in past month. The acts of discrimination included individuals being rejected because of HIV infection in access to social resources (e.g., jobs, education, social welfares) and their family being rejected because of the participants’ HIV infection. The potential answers to these two items were 3-point responses (“never” = 0, “once” = 1, and “at least twice” = 2). The responses to the items were summed to create a composite score with a higher score indicating a higher level of enacted stigma. Cronbach’s α of this measure was .68 for the current study sample.

Depression

The depression level was measured using the shortened version of Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10; Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, Citation1994). The CESD-10 is a 10-item self-report depression measure with a 4-point response option (0 = not at all, 1 = a little, 2 = some, 3 = a lot). The 10-item scale showed good predictive accuracy when compared to the full-length 20-item version of the CES-D (Andresen et al., Citation1994). A higher scale score suggests a higher level of depression. Cronbach’s α of this scale was .88 for the current study sample.

Anxiety

We employed the Zung Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) to measure anxiety level. The SAS is a 20-item scale assessing symptoms of anxiety on a 4-point response option (e.g., “how often do you feel heart pounding or racing,” “how often do you fear of losing control”). SAS has good psychometric properties and has been widely used in various Chinese populations (Sun et al., Citation2014). Cronbach’s α of the scale was .87 in our sample.

ART adherence

Recognizing the potential limitation of self-report ART adherence measures, multiple items were employed in the current study to assess the ART adherence. First, ART adherence was assessed by the percentage of prescribed ART doses taken within three specified time windows (i.e., the last three days, the last weekend, and the last month). Good adherence was defined as taking at least 90% of prescribed doses at a given time window. In addition, participants were asked whether they have ever missed a dose before (yes/no). A composite score (ranged from 0 to 4) was constructed by counting numbers of good adherence across the three time windows and the response of never missing a dose before. A higher score indicates a better ART adherence.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted to demonstrate the basic background characteristics of the participants. We also examined the relationships between parental disclosure and key measures including enacted stigma, depression, anxiety, and ART adherence. We employed Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to compare the differences between disclosed group and no-disclosed group in these measures. The analyses related to ART adherence were limited to participants who received ART regimen.

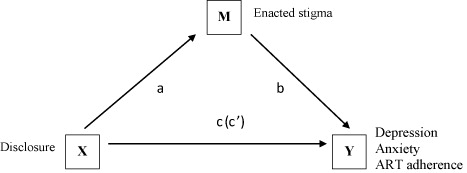

To test the potential mediation effect of enacted stigma, we first used Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficients (Pearson r) to examine the associations between all key measures (i.e., disclosure, enacted stigma, depression, anxiety, and ART adherence). Following the methodology developed by Baron and Kenny (Citation1986), we constructed four regression models to test if enacted stigma mediated the association between parental disclosure and depression level. We first regressed enacted stigma on disclosure to test path a (see ), followed by a second regression of depression on enacted stigma to test path b. Then we conducted a regression analysis with disclosure predicting depression to test path c. Finally, we regressed depression on both disclosure and enacted stigma to test the path cʹ.

Key background variables (i.e., gender, age, education attainment, marital status, and household size) were controlled in each regression model. Similarly, we performed regression analyses to test the mediation effects of enacted stigma on the associations of parental disclosure with anxiety and ART adherence. Regression coefficients for each path were estimated using least square methods. Sobel’s Z statistic was calculated to test the significance of each mediation effect (Preacher & Leonardelli, Citation2001). The regression coefficients for path a, b, c and cʹ were denoted as α, β, γ and γʹ, respectively. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Background characteristics

We presented the background characteristics for the sample in . About 59% of the parents were males. The average age was 38.90 years (SD = 8.33). Nearly 72% of the participants were of Han ethnicity, less than 7% reported any religion affiliation, and 78% were currently married. The mean education attainment was seven years (SD = 2.70). The majority (87%) of the parents lived in rural areas, and 22% reported that they did not work. There were on average 4.15 members in each family (SD = 2.08) including 1.92 children (SD = .99). Almost 56% of the participants reported that their monthly household income was less than 1000 yuan (approximately 160 US dollars in 2012). The average duration since their HIV diagnosis was 44 months (SD = 29.90). In addition, 48% of the participants reported that at least one of their family members was also infected with HIV.

Table 1. Background characteristics by disclosure group.

Of the overall sample, 111 participants reported that they had experienced HIV disclosure (“disclosed group”), 993 reported having not experienced disclosure (“no-disclosed group”). Among the disclosed group, 50 participants reported that they disclosed their HIV infection to their children and 61 did not disclose to their children by themselves but believed that their children had known about it. Nearly 54% of all the disclosures occurred within three months since HIV diagnosis. As shown in , most background characteristics were similar between disclosed group and no-disclosed group with several exceptions. Compared to the no-disclosed group, disclosed group was older (39.36 vs. 37.31 years), had a higher proportion of being currently unmarried (37.3% vs. 18.1%), and had a lower education attainment (6.59 vs. 7.14 years of formal schooling). In addition, the disclosed group had a longer duration since HIV diagnosis (51.58 vs. 45.92 months), and a lower proportion reporting any HIV infection in the family (39.6% vs. 45.92%) than the no-disclosed group.

Group differences of key measures

As shown in , parents differed in all the key measures by disclosure group. Specifically, the disclosed group reported significantly higher level of enacted stigma (2.26 vs. 2.07, F[1,1103] = 10.53, p = .001), depression (2.13 vs. 1.91, F[1,1102] = 6.25, p = .013), and anxiety (1.92 vs. 1.70, F[1,1101] = 11.97, p = .001) than the no-disclosed group. In addition, parental HIV disclosure had a significantly negative association with ART adherence (F[1,869] = 5.77, p = .017).

Table 2. Comparison of enacted stigma, depression, anxiety and ART adherence by disclosure group.

The role of enacted stigma

The correlation matrix among key measures was illustrated by . Enacted stigma was positively associated with parental HIV disclosure (r = .12, p < .001), depression (r = .24, p < .001), and anxiety (r = .23, p < .001). Enacted stigma was negatively associated with ART adherence (r = −.08, p < .05). Parental HIV disclosure was positively associated with depression (r = .11, p < .001) and anxiety (r = .13, p < .001), while negatively associated with ART adherence (r = −.08, p < .05).

Table 3. Correlation matrix among main measures.

The results of regression analyses were summarized in . Higher level of enacted stigma was associated with experiencing disclosure (α = .21, p < .001) and higher level of depression (β = .32, p < .001). In addition, parental HIV disclosure was significantly associated with depression (γ = .23, p < .001). The results of these three regression models supported the significance of path a, path b, and path c. When enacted stigma entered the regression model of depression, the regression coefficient of disclosure reduced from γ = .23 to γʹ = .16. Sobel’s statistic Z reached the significance level (Sobel Z = 3.84, p < .001). The findings suggested that enacted stigma partially mediated the association between parental HIV disclosure and depression.

Table 4. Coefficients in regression models for testing mediation effect of enacted stigma, controlling background characteristics.

Similarly, the results of regression analyses also supported the mediation effect of enacted stigma on the relationships of parental HIV disclosure with both anxiety and ART adherence. In the regression analysis of anxiety, the regression coefficient of disclosure reduced from γ = .21 to γʹ = .16 (Sobel Z = 3.80, p < .001); and in the regression analysis of ART adherence, the regression coefficient of disclosure (absolute value) reduced from γ = .21 to γʹ = .18 (Sobel Z = 2.56, p < .01) after our introducing enacted stigma into the regression models.

Discussion

The current study suggested that parents who had experienced disclosure to children reported higher level enacted stigma, worse mental health conditions, and poorer ART adherence. After controlling basic background characteristics, enacted stigma partially mediated the relationships between disclosure and both mental health and ART adherence.

As many empirical studies demonstrated, not all HIV disclosure benefit PLHIV, especially when the disclosure are involuntary or unplanned or conducted by people who have received no appropriate related training or counseling service. The association between parental HIV disclosure and parents’ mental health or medication adherence may depend on quality of disclosure, which can be affected by children’s knowledge of HIV (learned from school or social media), parents’ knowledge of HIV, their skills of communicating with children about the sensitive topic, social support from families and communities, as well as social environment (Qiao et al., Citation2013; Tenzek et al., Citation2013).

In the current study, majority of the participants lived in rural areas, with relatively low educational attainment and household income. The socioeconomic status may limit the access to accurate HIV knowledge for both parents and children. Social norms and culture may impede parents’ skills of disclosure because China is a society that generally discourages the disclosure of stressful events such as HIV infection, especially to children (Tse, Chong, & Fok, Citation2003). All these factors might negatively affect the quality of disclosure, contributing to poor outcomes of parental HIV disclosure. To the best of our knowledge, there was no HIV disclosure-related training or counseling service delivered to parents living with HIV in our study area. Therefore, it is difficult to argue that these disclosures were well-planned and developmentally appropriate.

As one critical component of social environment for HIV-infected parents, stigma plays an important role on parental HIV disclosure, not only on the decision-making, but also on the associations of parental HIV disclosure with mental health and medication behaviors among HIV-infected parents. The results of our mediational analysis regarding enacted stigma were consistent with existing literature on general HIV disclosure. HIV-related stigmatization and certain behaviors associated with acquisition of HIV (e.g., sexual promiscuity, injection drug use, and homosexual behavior), renders HIV disclosure a significant and recurrent stressor for PLHIV (Petrak, Doyle, Smith, Skinner, & Hedge, Citation2001). In a society with high level of HIV-related stigma and discrimination, HIV disclosure may result in social isolation, impede access to health services, and diminish sense of personal control for PLHIV (Greeff et al., Citation2008), and encroach on their social relationships, as well as educational, occupational, and financial opportunities and welfares (Kyaddondo et al., Citation2013; Sandelowski et al., Citation2004).

Our findings should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations. First, our sample may not be representative of parents living with HIV in other areas of China. For instance, a large number of HIV-infected parents in central rural China were infected through commercial blood donation. The moral meanings and stigma regarding HIV infection may be different for those individuals as they were often viewed as “innocent” victims. Second, the size of disclosed group was small due to the low rate of parental HIV disclosure, which might reduce the power of data analysis. However, our significant findings suggested robust results even with such reduced statistical power. Third, limited by cross-sectional data, the current study was not able to establish a causal relationship between parental HIV disclosure and the mental health or ART adherence among HIV-infected parents. For example, parental HIV disclosure may result in mental health problems due to stress related to coping with child’s reactions. Alternatively, parents with better mental health do not feel the need of support from their children and therefore they may decide not to disclose. Similarly, HIV-infected parents with better ART adherence and thus better health may be confident in concealing their HIV infection from children thus decide not to disclose. In addition, we also need longitudinal studies to test if HIV-related stigma in the community may lead to parental disclosure (as a way of coping with stigma).

Despite these limitations, our findings have several implications for parental HIV disclosure intervention among HIV-infected parents. First, the high proportion of involuntary, unplanned disclosures among the HIV-infected parents highlights the importance of appropriate disclosure-related training and counseling service for parents living with HIV/AIDS. Second, health-care professionals including local health-care workers should not push the parents to disclose HIV status to children without addressing the issues of stigma and discrimination, the stress for parents, and the possible negative reaction from children. Third, disclosure intervention needs to incorporate with components of stigma and discrimination reduction to have maximum effectiveness on improving physical and psychosocial well-beings of both the parents and children. A supportive environment for HIV-infected parents is vital to ensure that they and their children will fully benefit from parental HIV disclosure.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Joanne Zwemer for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alonzo, A. A., & Reynolds, N. R. (1995). Stigma, HIV and AIDS: An exploration and elaboration of a stigma trajectory. [Review]. Social Science & Medicine, 41, 303–315. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)00384-6

- Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(2), 77–84.

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Clifford, G., Craig, G. M., McCourt, C., & Barrow, G. (2013). What are the benefits and barriers of communicating parental HIV status to seronegative children and the implications for Jamaica? A narrative review of the literature in low/middle income countries. West Indian Medical Journal, 62, 357–363. doi:10.7727/WIMJ.2013.087

- Dima, A. L., Stutterheim, S. E., Lyimo, R., & de Bruin, M. (2014). Advancing methodology in the study of HIV status disclosure: The importance of considering disclosure target and intent. Social Science & Medicine, 108, 166–174. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.045

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Greeff, M., Phetlhu, R., Makoae, L. N., Dlamini, P. S., Holzemer, W. L., Naidoo, J. R., … Chirwa, M. L. (2008). Disclosure of HIV status: Experiences and perceptions of persons living with HIV/AIDS and nurses involved in their care in Africa. Qualitative Health Research, 18, 311–324. doi:10.1177/1049732307311118

- Grossman, C. I., & Stangl, A. L. (2013). Editorial: Global action to reduce HIV stigma and discrimination. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16, 18881. doi:10.7448/IAS.16.3.18881

- Guangxi Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2009, July 19–21). Update on HIV/AIDS epidemic in Guangxi. Paper presented at the NIAAA venue-based HIV and alcohol risk reduction among female sex workers in China, Guilin, Guangxi.

- Katz, I. T., Ryu, A. E., Onuegbu, A. G., Psaros, C., Weiser, S. D., Bangsberg, D. R., & Tsai, A. C. (2013). Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: Systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16, 18640. doi:10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640

- Kyaddondo, D., Wanyenze, R. K., Kinsman, J., & Hardon, A. (2013). Disclosure of HIV status between parents and children in Uganda in the context of greater access to treatment. Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance, 10(Suppl. 1), S37–S45. doi:10.1080/02664763.2012.755323

- Lee, S. J., Li, L., Iamsirithaworn, S., & Khumtong, S. (2013). Disclosure challenges among people living with HIV in Thailand. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 19, 374–380. doi:10.1111/ijn.12084

- Murphy, D. A., Marelich, W. D., & Hoffman, D. (2002). A longitudinal study of the impact on young children of maternal HIV serostatus disclosure. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(1), 55–70. doi:10.1177/1359104502007001005

- Okoror, T. A., Belue, R., Zungu, N., Adam, A. M., & Airhihenbuwa, C. O. (2014). HIV positive women’s perceptions of stigma in health care settings in Western Cape, South Africa. Health Care for Women International, 35(1), 27–49. doi:10.1080/07399332.2012.736566

- Petrak, J. A., Doyle, A. M., Smith, A., Skinner, C., & Hedge, B. (2001). Factors associated with self-disclosure of HIV serostatus to significant others. British Journal of Health Psychology, 6(Pt 1), 69–79. doi:10.1348/135910701169061

- Preacher, K. J., & Leonardelli, G. J. (2001). Calculation for the Sobel test: An interactive calculation tool for mediation tests [Computer software]. Retrieved September 20, 2014, from http://www.unc.edu/preacher/sobel/sobel.htm

- Qiao, S., Li, X., & Stanton, B. (2013). Disclosure of parental HIV infection to children: A systematic review of global literature. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 369–389. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-0069-x

- Qiao, S., Li, X., & Stanton, B. (2014). Practice and perception of parental HIV disclosure to children in Beijing, China. Qualitative Health Research, 24, 1276–1286. doi:10.1177/1049732314544967

- Sandelowski, M., Lambe, C., & Barroso, J. (2004). Stigma in HIV-positive women. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36(2), 122–128. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04024.x

- Shacham, E., Small, E., Onen, N., Stamm, K., & Overton, E. T. (2012). Serostatus disclosure among adults with HIV in the era of HIV therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 26(1), 29–35. doi:10.1089/apc.2011.0183

- Steward, W. T., Bharat, S., Ramakrishna, J., Heylen, E., & Ekstrand, M. L. (2013). Stigma is associated with delays in seeking care among HIV-infected people in India. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care, 12(2), 103–109. doi:10.1177/1545109711432315

- Sun, W., Wu, M., Qu, P., Lu, C., & Wang, L. (2014). Psychological well-being of people living with HIV/AIDS under the new epidemic characteristics in China and the risk factors: A population-based study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 28, 147–152. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2014.07.010

- Tenzek, K. E., Herrman, A. R., May, A. R., Feinerd, B., & Allenb, M. (2013). Examining the impact of parental disclosure of HIV on children: A meta-analysis. Western Journal of Communication, 77, 323–339. doi:10.1080/10570314.2012.719092

- Tsai, A. C., Bangsberg, D. R., Kegeles, S. M., Katz, I. T., Haberer, J. E., Muzoora, C., … Weiser, S. D. (2013). Internalized stigma, social distance, and disclosure of HIV seropositivity in rural Uganda. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46, 285–294. doi:10.1007/s12160-013-9514-6

- Tse, C. Y., Chong, A., & Fok, S. Y. (2003). Breaking bad news: A Chinese perspective. Palliative Medicine, 17, 339–343. doi:10.1191/0269216303pm751oa