ABSTRACT

Evidence-based approaches are needed to address the high levels of sexual risk behavior and associated HIV infection among orphaned and vulnerable adolescents. This study recruited adolescents from a support program for HIV-affected families and randomly assigned them by cluster to receive one of the following: (1) a structured group-based behavioral health intervention; (2) interpersonal psychotherapy group sessions; (3) both interventions; or (4) no new interventions. With 95% retention, 1014 adolescents were interviewed three times over a 22-month period. Intent-to-treat analyses, applying multivariate difference-in-difference probit regressions, were performed separately for boys and girls to assess intervention impacts on sexual risk behaviors. Exposure to a single intervention did not impact behaviors. Exposure to both interventions was associated with risk-reduction behaviors, but the outcomes varied by gender: boys reported fewer risky sexual partnerships (β = −.48, p = .05) and girls reported more consistent condom (β = 1.37, p = .02). There was no difference in the likelihood of sexual debut for either gender. Providing both psychological and behavioral interventions resulted in long-term changes in sexual behavior that were not present when either intervention was provided in isolation. Multifaceted approaches for reducing sexual risk behaviors among vulnerable adolescents hold significant promise for mitigating the HIV epidemic among this priority population.

Introduction

Adolescent orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) are at heightened risk of HIV infection. Orphaned youth have been found to have higher levels of risky sexual behavior and nearly twofold greater odds of HIV infection compared to their non-orphaned peers (Operario, Underhill, Chuong, & Cluver, Citation2011). Evidence also points to elevated sexual risk behavior among children with an AIDS-sick parent (Cluver, Orkin, Boyes, Gardner, & Meinck, Citation2011). Effective HIV prevention strategies are urgently needed to curb the spread of the epidemic among this priority population.

Recent experimental studies provide evidence for the impact of economic and educational interventions on adolescents’ sexual intentions, partner selection and age at sexual debut (Cho et al., Citation2011; Cluver et al., Citation2013; Hallfors et al., Citation2011; Handa, Halpern, Pettifor, & Thirumurthy, Citation2014; Ssewamala, Alicea, Bannon Jr, & Ismayilova, Citation2008). However, the preventive effects of these interventions may be maximized if delivered in combination with interventions that target other risk factors. Evidence from Zimbabwe highlights how providing both an economic and behavioral intervention can reduce sexual risk behaviors among vulnerable adolescent girls (Dunbar et al., Citation2014).

Behavioral interventions are the cornerstone of HIV prevention, providing critical knowledge and skills (Ross, Dick, & Ferguson, Citation2006). About 80% of young women between the ages of 15 and 24 in countries with generalized epidemics lack the ability to identify effective methods of HIV prevention (UNICEF, UNAIDS & WHO, Citation2002). Given their heightened risk for HIV, there is an even greater imperative for adolescent OVC to receive HIV education. However, adding interventions that address their psychological health may be even more powerful.

Psychological distress is a key risk factor for poor sexual decision-making and is particularly salient for OVC given their well-documented higher risk for mental health problems (Chi & Li, Citation2013; Cluver & Gardner, Citation2007). A population-based study in Zimbabwe illustrated the pathway between psychological distress and sexual risk behaviors among female orphans (Robertson, Gregson, & Garnett, Citation2010). Similarly, research from Kenya found that orphans’ psychological difficulties affected their self-efficacy to engage in safer sex practices (Puffer et al., Citation2012). These findings indicate the importance of addressing psychological health among OVC as part of a coordinated effort to decrease sexual risk-taking.

This study employs a cluster randomized control trial (RCT) to evaluate the effectiveness of two interventions, offered independently and in combination, on sexual risk behaviors among adolescent OVC in South Africa, home of the world's largest HIV epidemic (UNAIDS, Citation2013). The first is a psychological intervention designed to mitigate mental health problems. The second is a behavioral intervention designed to build participants’ HIV prevention knowledge and related skills. Both are situated within a broader OVC program offering educational and economic support to adolescents and their families.

Methods

Interventions

The two interventions under study were delivered by World Vision South Africa and offered in addition to their community-based OVC programming model, Networks of Hope. The model includes home visits by trained volunteers, who address the economic security of beneficiaries (e.g., helping them obtain social grants); support academic achievement (e.g., providing uniforms and educational supplies); and provide referrals for health care and other social services. The program principally targets HIV-affected children, including those who have lost a parent or are living with someone who is chronically ill.

The first intervention, Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Groups (IPTG), consists of 16 weekly 90-minute group sessions led by a trained lay adult community facilitator. The sessions are designed to provide participants with opportunities to learn and practice interpersonal skills for resolving distress, and to facilitate the provision of emotional support between group members. Relying on a manual of key principles and discussion points, facilitators probe participants to identify people who are important in their lives, understand links between their psychological state and current problems, practice problem-solving, and to help one another throughout the process. Implementers divided the groups by gender given the local sensitivity of mental health issues and potential for romantic interests or gender norms to squelch dialogue. Research in developing countries has demonstrated the efficacy of IPTG implemented by lay facilitators in alleviating depression among those with moderate-to-high depression symptoms (Bass et al., Citation2006; Bolton et al., Citation2007; Petersen, Bhana, & Baillie, Citation2012). Guided by the premise that all OVC could benefit from psychosocial support, depression symptomology was not a precondition for IPTG enrollment in this study.

The second intervention, called Vhutshilo (meaning “Life” in Venda), is a curriculum-based behavioral intervention developed by a South African non-profit organization, Centre for the Support of Peer Education (CSPE), through a national consultative process and in collaboration with experts from the Harvard School of Public Health. The Vhutshilo program was designed specifically for OVC aged 14 and older in South Africa, and addresses HIV risk factors and pathways considered particularly relevant for this population. It consists of 13 weekly 60 minute sessions covering topics including: alcohol and substance abuse; crime and sexual violence; HIV/AIDS; healthy sexual relationships; transactional sex; and condom use. Guided by a trained young adult facilitator, participants engage in critical reflection on these topics through following a fictionalized narrative that includes complex, realistic adolescent characters. These characters bear strategic similarities to adolescent OVC and make unpredictable decisions, both healthy and unhealthy, based on a variety of influences. Thus, the intervention encourages social learning through reflection, as participants consider the choices characters made, challenge themselves and each other to imagine themselves in similar situations, and think through their own possible choices and consequences. Mixed-gender groups were held as encouraged by the program developers to foster dialogue and understanding of each gender's perspective. Prior evaluation suggests positive effects among participants with respect to HIV knowledge and attitudes about sexual risk behavior (Swartz et al., Citation2012).

Participants

The study sample (n = 1016) consisted of adolescents across 84 contiguous villages in two rural districts in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. The sample was drawn from World Vision's beneficiary database of households enrolled in the Networks of Hope program for an average of two years. Beneficiaries were eligible for the study if they were age 14–17 years old by 1 January 2012. They were excluded from the study if they were not living at home; many rural adolescents attended boarding schools beyond World Vision's service provision catchment area.

Study design and randomization

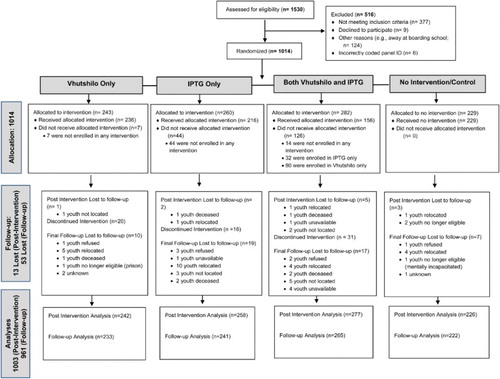

A cluster RCT with a four-group factorial design was applied to examine the impact of the two key interventions in isolation and in combination on adolescent sexual risk behavior. Adolescents were assigned to one of 57 drop-in centers based on the proximity of their residence to the nearest intervention delivery location; an average of 18 adolescents was assigned to each center. To guarantee greater geographical balance, the centers were stratified by size and study district prior to randomization. Within each stratum, adolescents were randomized by center (using a random number generator) into one of the four experimental conditions: (1) Vhutshilo only; (2) IPTG only; (3) IPTG followed immediately by Vhutshilo; and (4) no new interventions (standard care – control group). All participants continued to receive the existing basic economic and educational support services provided by World Vision. Original beneficiary lists suggested a potential sampling frame of 1530 adolescents (). Sample size calculations were powered to detect an 8% difference in sexual debut based on 80% power, a design effect of 1.5, alpha of 1.96 and 296 minimum individuals expected per group.

Data collection and ethics

Participating adolescents and their caregivers completed three rounds of surveys: prior to intervention; directly following the intervention period (10 months after the baseline assessment) and one year later (22 months after the baseline assessment). Surveys were administered at the participants’ residence and in their local language, either isiXhosa or Sesotho. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with primary caregivers to obtain socio-demographic information. Adolescents reported their sexual behavior using audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) technology. Ethical approval was obtained from the Tulane University Institutional Review Board in the USA and the Human Science Research Council in South Africa.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Primary sexual risk behavior outcomes included sexual debut and consistent condom use. Sexual debut was measured by asking participants whether they had ever had sex. Consistent condom use was defined as reported use of a condom at every episode of sexual intercourse in the prior six months, and thereby limited to participants who reported recent sexual activity. Engagement in risky sexual partnerships was examined as a secondary outcome of interest and included an affirmative response to one or more of the following experiences: ever had sex with someone other than boyfriend/girlfriend, had two or more partners in the same month in the past six months, and/or had a history of transactional sex (i.e., females reported receiving and males reported giving money, food or other gifts for sex).

Statistical analyses

Frequencies display the demographic and sexual risk profile across the intervention groups. Intent-to-treat analyses, applying random effects difference-in-difference probit regressions that controlled for important covariates, were performed for adolescent boys and girls separately to assess for intervention impact on sexual risk behaviors. Models included a robust cluster variance estimator to adjust standard errors for within-cluster correlation at baseline (Williams, Citation2000), and controlled for the baseline value of the outcome, and time variant factors of orphan status and having an AIDS-sick caregiver – established risk factors for the sexual behaviors under study (Cluver et al., Citation2011; Operario et al., Citation2011; Puffer et al., Citation2012). Information on orphan status and having an AIDS-sick caregiver was derived from the caregiver survey. Caregivers indicating an illness of three months in a row or longer in the past 12 months and three or more AIDS-related signs or symptoms were classified as AIDS-sick, based on a verbal autopsy scale used previously in South Africa (Cluver et al., Citation2011; Hosegood, Vanneste, & Timaeus, Citation2004). Significant group by time interactions signify changes in treatment category versus the control and predicted probabilities highlight prevalence differences across group and time.

Results

Participant flow

As shown in , the retention rate was 95%, with 961 of the original 1014 adolescents in the baseline sample participating in both follow-up surveys. The interventions were made available to all selected beneficiaries and 82% of baseline respondents participated in the interventions as assigned, with non-compliance most common among those enrolled in both interventions.

Study cohort

provides the demographics of the sample at baseline by intervention group. The average age was 15.5 and 48% were female. Nearly 80% of the adolescents had lost a parent; 25% were double orphans, 40% had lost only their father and the remaining 15% had lost only their mother. About 14% of the caregivers were classified as AIDS-sick.

Table 1. Demographic profile of the sample by intervention group at baseline.

Descriptives for the three sexual risk outcomes under study by survey round, gender and intervention are displayed in . Overall, about 29% of girls and 35% of boys had sexually debuted at baseline and this rose to about 50% over the study period. At the final survey round nearly one-quarter of boys and one-fifth of girls reported engaging in a risky sexual partnership and half of the recently sexually active adolescents reported consistent condom use.

Table 2. Sexual risk behavior at each survey round by participant gender and intervention group.

Intervention effects

Multivariate results presented in demonstrate significant intervention effects among only those enrolled in both interventions, and these effects varied by gender. Significant increases in consistent condom use for girls enrolled in both interventions relative to the control were found at both follow-up surveys (β = 1.21, standard error = .52, p = .02 and β = 1.37, standard error = .57, p = .02, respectively). Predicted probabilities shown in suggest a nearly 32% increase in consistent condom use among these female participants between baseline and the post-intervention survey with this effect persisting at the final survey round; in contrast to only 7% sustained increase for the control group. For boys, the prevalence of risky sexual partnerships among those enrolled in both interventions was significantly lower than the control group at the final follow-up survey (β = −.48, standard error = .24, p = .05). Between baseline and final follow-up, the predicted probability rose by nearly 9% in the control group, whereas it stayed about the same among boys in both interventions (). None of the aforementioned effects extend to the other gender and sexual debut was unaffected by intervention enrollment.

Table 3. Multivariate difference-in-difference probit regression results for intervention effects at each survey round.

Table 4. Predicted change for outcomes significantly affected by the intervention.

Discussion

Findings from this cluster RCT suggest that strategically packaging psychological and behavioral interventions together may achieve greater reductions in sexual risk behavior among adolescent OVC than either approach could achieve independently. Girls who received both interventions were significantly more likely than the comparison group to report consistent condom use and boys enrolled in both interventions were significantly less likely to report risky partnerships.

These results underscore the potential of incorporating psychological health interventions as part of a comprehensive strategy for mitigating HIV risk among OVC. Mediators between psychological distress and unhealthy sexual decision-making include high rates of substance use, low self-esteem, increased susceptibility to pressure to have sex, comfort seeking, and self-destructive attitudes (Brawner, Gomes, Jemmott, Deatrick, & Coleman, Citation2012; Cluver & Operario, Citation2008). Small group interventions can also promote self-esteem and social support, necessary precursors to behavior change (Harrison, Newell, Imrie, & Hoddinott, Citation2010). Future analyses can explore potential psychosocial intermediaries to reduced sexual risk behavior among intervention participants and any disparate effects given baseline mental health status.

While findings from this study suggest that adopting a multifaceted approach in addressing sexual risk behaviors among adolescent OVC is beneficial, a number of gaps remain. Sexual debut was unaffected, consistent with results from 15 abstinence-plus behavioral intervention studies in the USA and a recent behavioral and economic program for vulnerable girls in Zimbabwe (Dunbar et al., Citation2014; Underhill, Operario, & Montgomery, Citation2007). The isolated impact by gender on consistent condom use and risky sexual partnerships is particularly concerning given fairly equivalent risk behavior for boys and girls. Intervention effects that vary by gender are not unique to this study; a similar finding pertaining to sexual risk attitudes was seen among OVC participants in an economic empowerment intervention in Uganda (Ssewamala et al., Citation2010). These results substantiate the call for gender-sensitive HIV prevention programming (Eckman, Huntley, & Bhuyan, Citation2004; Weiss & Gupta, Citation1998). The introduction of gender-specific sessions and activities tailored to address predominant gender norms and concerns could increase intervention efficacy.

The application of a factorial cluster RCT among nearly 1000 adolescent OVC with 95% retention rate is a considerable contribution to the evidence-base for OVC programming, although the study is not without limitations. Nearly one-third of the adolescents within the original sample frame were found to be ineligible to participate, leading to a smaller than anticipated sample size. Most were ineligible due to residence at schools outside of their community, highlighting the need for supplemental school-based programs to reach this population. Further, while conducting gender sub-group analysis is consistent with recent recommendations for increasing the programming evidence-base (Hardee, Gay, Croce-Galis, & Afari-Dwamena, Citation2014), it reduced statistical power. At the same time, the divergent effects found between girls and boys highlight the importance of investigating gender differences in response to HIV prevention interventions. Follow-up one-year post-intervention may be too short to capture the full range of potential program effects. Reliance on self-reports of sexual behavior also presents potential response bias, although this risk is minimized by the use of ACASI which has repeatedly demonstrated differential reporting success for high-risk behaviors compared to more traditional questionnaire delivery methods (Hewett, Mensch, & Erulkar, Citation2003; Metzger et al., Citation2000; Van der Elst et al., Citation2009). The use of biomarkers and tracking of adolescents into their twenties would provide even more robust estimates of program impact.

Key features of intervention implementation should also be considered in the interpretation of these results and for replication of the intervention approach. Intervention exposure was not optimal, but the application of intent-to-treat analyses helps simulate results that may be expected in real-life settings. Intervention enrollment rates signify the need for programmers to preempt potential attendance barriers prior to intervention roll-out. However, this study captured World Vision's first experience implementing these interventions in these communities. Facilitation and logistics are likely to improve with time and experience. Continued intervention proficiency and refinement could lead to even greater impact, highlighting the value of evaluating these efforts as an iterative process. It is further possible that the positive program effects found among dual intervention participants may at least in part be explained by the extended group interaction of 29 weeks rather than the content of the interventions. The prolonged opportunity for social engagement may be a critical component of the program's success, particularly given the documented social isolation and stigma experienced by HIV-affected children (Cluver, Bowes, & Gardner, Citation2010; Foster, Makufa, Drew, Mashumba, & Kambeu, Citation1997; Thurman et al., Citation2006). However, a synergistic effect is not unlikely given that the two interventions have independently shown positive impact on other determinants of risk, including HIV knowledge, sexual behavior attitudes, and psychological health (Bass et al., Citation2006; Bolton et al., Citation2007; Petersen et al., Citation2012; Swartz et al., Citation2012).

The interventions under investigation were offered as an add-on to basic needs services, which means similar results may not be found without this precondition. Though, efforts to address economic and educational needs are critical and arguably a necessary platform for promoting the potential efficacy of supplementary behavioral and psychological interventions. World Vision's service delivery model is characteristic of OVC programs in the region: it is community-based, relies on local community members, and delivers services directly to OVC and their households. Thus, findings from this study have relevance across a range of implementing partners. The two interventions, IPTG and Vhutshilo, represent a promising combined service delivery package for supporting sexual risk reduction among OVC. Scale-up of these and other theory-based psychological and behavioral intervention packages is encouraged. Accompanying evaluations should investigate cost-effectiveness, intervention attributes, and intermediary outcomes that can most effectively contribute to reductions in risk behavior in this highly vulnerable population.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bass, J., Neugebauer, R., Clougherty, K. F., Verdeli, H., Wickramaratne, P., Ndogoni, L., … Bolton, P. (2006). Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: 6-month outcomes. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 188(6), 567–573. doi:10.1192/bjp.188.6.567

- Bolton, P., Bass, J., Betancourt, T., Speelman, L., Onyango, G., Clougherty, K., … Verdeli, H. (2007). Interventions for depression symptoms among adolescent survivors of war and displacement in northern Uganda. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 298(5), 519–527. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.519

- Brawner, B. M., Gomes, M. M., Jemmott, L. S., Deatrick, J. A., & Coleman, C. L. (2012). Clinical depression and HIV risk-related sexual behaviors among African-American adolescent females: Unmasking the numbers. AIDS Care, 24(5), 618–625. doi:10.1080/09540121.2011.630344

- Chi, P., & Li, X. (2013). Impact of parental HIV/AIDS on children's psychological well-being: A systematic review of global literature. AIDS and Behavior, 17(7), 2554–2574. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0290-2

- Cho, H., Hallfors, D. D., Mbai, I. I., Itindi, J., Milimo, B. W., Halpern, C. T., & Iritani, B. J. (2011). Keeping adolescent orphans in school to prevent human immunodeficiency virus infection: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Kenya. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(5), 523–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.007

- Cluver, L., Bowes, L., & Gardner, F. (2010). Risk and protective factors for bullying victimization among AIDS-affected and vulnerable children in South Africa. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(10), 793–803. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.04.002

- Cluver, L., Boyes, M., Orkin, M., Pantelic, M., Molwena, T., & Sherr, L. (2013). Child-focused state cash transfers and adolescent risk of HIV infection in South Africa: A propensity-score-matched case-control study. The Lancet Global Health, 1(6), e362–e370. doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(13)70115-3

- Cluver, L., & Gardner, F. (2007). The mental health of children orphaned by AIDS: A review of international and southern African research. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 19(1), 1–17. doi: 10.2989/17280580709486631

- Cluver, L., & Operario, D. (2008). The intergenerational link between the impacts of AIDS on children, and their subsequent vulnerability to HIV infection. Oxford: Joint Learning Initiative for Children Affected by AIDS.

- Cluver, L., Orkin, M., Boyes, M., Gardner, F., & Meinck, F. (2011). Transactional sex amongst AIDS-orphaned and AIDS-affected adolescents predicted by abuse and extreme poverty. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 58(3), 336–343. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822f0d82

- Dunbar, M. S., Kang Dufour, M.-S., Lambdin, B., Mudekunye-Mahaka, I., Nhamo, D., & Padian, N. S. (2014). The SHAZ! project: Results from a pilot randomized trial of a structural intervention to prevent HIV among adolescent women in Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE, 9(11), e113621. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0113621

- Eckman, A., Huntley, B., & Bhuyan, A. (2004). How to integrate gender into HIV/AIDS programs: Using lessons learned from USAID and partner organizations. Washington, DC: Gender and HIV/AIDS Task Force, Interagency Gender Working Group (IGWG), & United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

- Foster, G., Makufa, C., Drew, R., Mashumba, S., & Kambeu, S. (1997). Perceptions of children and community members concerning the circumstances of orphans in rural Zimbabwe. AIDS Care, 9(4), 391–405. doi: 10.1080/713613166

- Hallfors, D., Cho, H., Rusakaniko, S., Iritani, B., Mapfumo, J., & Halpern, C. (2011). Supporting adolescent orphan girls to stay in school as HIV risk prevention: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Zimbabwe. American Journal of Public Health, 101(6), 1082–1088. doi:10.2105/ajph.2010.300042

- Handa, S., Halpern, C. T., Pettifor, A., & Thirumurthy, H. (2014). The government of Kenya's cash transfer program reduces the risk of sexual debut among young people age 15–25. PLoS ONE, 9(1), e85473. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085473

- Hardee, K., Gay, J., Croce-Galis, M., & Afari-Dwamena, N. A. (2014). What HIV programs work for adolescent girls? JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 66(Suppl. 2), S176–S185. doi:10.1097/qai.0000000000000182

- Harrison, A., Newell, M. L., Imrie, J., & Hoddinott, G. (2010). HIV prevention for South African youth: Which interventions work? A systematic review of current evidence. BMC Public Health, 10, 102. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-102

- Hewett, P. C., Mensch, B. S., & Erulkar, A. S. (2003). Consistency in the reporting of sexual behavior among adolescent girls in Kenya: A comparison of interviewing methods. Working Papers. Research Division. New York, NY: Population Council.

- Hosegood, V., Vanneste, A., & Timaeus, I. (2004). Levels and causes of adult mortality in rural South Africa: The impact of AIDS. AIDS, 18, 663–671. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403050-00011

- Metzger, D. S., Koblin, B., Turner, C., Navaline, H., Valenti, F., Holte, S., … Seage, G. R. I. (2000). Randomized controlled trial of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing: Utility and acceptability in longitudinal studies. American Journal of Epidemiology, 152(2), 99–106. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.2.99

- Operario, D., Underhill, K., Chuong, C., & Cluver, L. (2011). HIV infection and sexual risk behavior among youth who have experienced orphanhood: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 14(25). doi:10.1186/1758-2652-14-25

- Petersen, I., Bhana, A., & Baillie, K. (2012). The feasibility of adapted group-based interpersonal therapy (IPT) for the treatment of depression by community health workers within the context of task shifting in South Africa. Community Mental Health Journal, 48(3), 336–341. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9429-2

- Puffer, E. S., Drabkin, A. S., Stashko, A. L., Broverman, S. A., Ogwang-Odhiambo, R. A., & Sikkema, K. J. (2012). Orphan status, HIV risk behavior, and mental health among adolescents in rural Kenya. Journal of pediatric psychology, 37(8), 868–878. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jss077

- Robertson, L., Gregson, S., & Garnett, G. P. (2010). Sexual risk among orphaned adolescents: Is country-level HIV prevalence an important factor? AIDS Care, 22(8), 927–938. doi: 10.1080/09540121003758622

- Ross, D., Dick, B., & Ferguson, J. (2006). Preventing HIV/AIDS in young people: A systematic review of the evidence from developing countries. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Ssewamala, F., Ismayilova, L., McKay, M., Sperber, E., Bannon, W., & Alicea, S. (2010). Gender and the effects of an economic empowerment program on attitudes toward sexual risk-taking among AIDS-orphaned adolescent youth in Uganda. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(4), 372–378. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.010

- Ssewamala, F. M., Alicea, S., Bannon Jr, W. M., & Ismayilova, L. (2008). A novel economic intervention to reduce HIV risks among school-going AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42(1), 102–104. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.011

- Swartz, S., Deutsch, C., Makoae, M., Michel, B., Harding, J. H., Garzouzie, G., … Van der Heijden, I. (2012). Measuring change in vulnerable adolescents: Findings from a peer education evaluation in South Africa. SAHARA J: Journal Of Social Aspects Of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance, 9(4), 242–254. doi:10.1080/17290376.2012.745696

- Thurman, T. R., Snider, L., Boris, N., Kalisa, E., Nkunda Mugarira, E., Ntaganira, J., & Brown, L. (2006). Psychosocial support and marginalization of youth-headed households in Rwanda. AIDS Care, 18(3), 220. doi:10.1080/09540120500456656

- UNAIDS. (2013). Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

- Underhill, K., Operario, D., & Montgomery, P. (2007). Systematic review of abstinence-plus HIV prevention programs in high-income countries. PLoS medicine, 4(9), e275. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040275

- UNICEF, UNAIDS, & WHO. (2002). Young people and HIV/AIDS: Opportunity in crisis. New York, NY: UNICEF.

- Van der Elst, E. M., Okuku, H. S., Nakamya, P., Muhaari, A., Davies, A., McClelland, R. S., … Sanders, E. J. (2009). Is audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) useful in risk behaviour assessment of female and male sex workers, Mombasa, Kenya? PLoS ONE, 4(5), e5340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005340

- Weiss, E., & Gupta, G. R. (1998). Bridging the gap: addressing gender and sexuality in HIV prevention. Findings from the women and AIDS research program (31p.). Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women [ICRW].

- Williams, R. L. (2000). A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics, 56(2), 645–646. doi:10.2307/2677014