ABSTRACT

Policy-makers and clinicians are faced with a gap of evidence to guide policy on standards for HIV outpatient care. Ongoing debates include which settings of care improve health outcomes, and how many HIV-infected patients a health-care provider should treat to gain and maintain expertise. In this article, we evaluate the studies that link health-care facility and care provider characteristics (i.e., structural factors) to health outcomes in HIV-infected patients. We searched the electronic databases MEDLINE, PUBMED, and EMBASE from inception until 1 January 2015. We included a total of 28 observational studies that were conducted after the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy in 1996. Three aspects of the available research linking the structure to quality of HIV outpatient care were evaluated: (1) assessed structural characteristics (i.e., health-care facility and care provider characteristics); (2) measures of quality of HIV outpatient care; and (3) reported associations between structural characteristics and quality of care. Rather than scarcity of data, it is the diversity in methodology in the identified studies and the inconsistency of their results that led us to the conclusion that the scientific evidence is too weak to guide policy in HIV outpatient care. We provide recommendations on how to address this heterogeneity in future studies and offer specific suggestions for further reading that could be of interest for clinicians and researchers.

Introduction

The availability of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has resulted in remarkable decreases in HIV-related morbidity and mortality (Thompson et al., Citation2012). Unfortunately, the complexity of the management of HIV infection has grown along with the advances in treatment (Hecht, Wilson, Wu, Cook, & Turner, Citation1999). Individuals infected with HIV face a lifetime of treatment with cART and monitoring of disease progression. Health-care providers are confronted with challenges related to cART including toxicities, drug–drug interactions and drug resistance, and comorbidities among the aging HIV-positive population.

In order to achieve optimal health outcomes, care for HIV-infected patients should be provided at health-care facilities and by care providers with sufficient expertise (Hecht et al., Citation1999). Previous studies have evaluated the impact of health-care facility and care provider characteristics on the quality of care for HIV-infected patients. However, questions regarding qualifications to treat HIV-infected patients remain. Ongoing debates include which settings of care (e.g., primary/secondary/tertiary facilities; facility volume) improve health outcomes, and how many HIV-infected patients a health-care provider should treat (provider HIV caseload) to gain and maintain expertise.

The first studies addressing these issues took place before the introduction of cART. Studies showed lower rates of mortality in facilities with greater volumes of HIV-infected inpatients and in facilities with units dedicated to HIV/AIDS care (Bennett et al., Citation1989, Citation1992, Citation1995; Cunningham, Tisnado, Lui, Nakazono, & Carlisle, Citation1999; Hogg et al., Citation1998; Stone, Seage, Hertz, & Epstein, Citation1992; Turner & Ball, Citation1992). In addition, greater clinician HIV experience was positively associated with survival (Kitahata et al., Citation1996; Laine et al., Citation1998).

With the advent of cART, the focus shifted from measurement of survival to assessment of virologic success and physician adherence to guidelines. Studies showed that patients treated by health-care providers with more training/expertise in HIV/AIDS care had greater plasma viral load control and were more likely to be on cART (Landon et al., Citation2003, Citation2005).

Currently, there are a growing number of studies assessing care delivery models and interventions in outpatient HIV care. The aims of the interventions, as well as the way they are operationalized, are very diverse. “Adherence support,” “case management,” “task shifting,” and “integration of care” are examples of widely studied interventions. They are beyond the scope of this review and have been reviewed separately elsewhere (Callaghan, Ford, & Schneider, Citation2010; Kredo, Adeniyi, Bateganya, & Pienaar, Citation2014; Lazarus, Safreed-Harmon, Nicholson, & Jaffar, Citation2014; Mdege, Chindove, & Ali, Citation2013; Soto, Bell, & Pillen, Citation2004).

In this article, we give an overview of the scientific literature linking health-care facility and care provider characteristics to the quality of HIV outpatient care. It is the first to focus exclusively on studies that took place after the introduction of cART. We used the structure–process–outcome framework (Donabedian, Citation1988) to distinguish between the characteristics and outcomes that have been evaluated. Structure refers to stable characteristics of health systems (e.g., staff and facility volume). Process describes the activities of care providers and patients in health care. Outcome refers to the effects of care on the health status of patients.

We aim to provide a critical evaluation of three aspects of the available research linking the structure to quality of HIV outpatient care: (1) assessed structural characteristics (i.e., health-care facility and care provider characteristics); (2) measures of quality of HIV outpatient care; and (3) reported associations between structural characteristics and quality of care. For this third part of the review, we focused exclusively on studies that measured virologic success.

Methods

We searched the electronic databases MEDLINE, PUBMED and EMBASE from the dates of their inception until 1 January 2015, using the search terms presented in . Titles, abstracts, and full text studies were screened. Reference lists of relevant studies were screened for additional relevant citations.

Box 1. Search terms

We extracted general parameters (study design, country, and population); structural characteristics on the health facility level (setting, volume, specialization, level of care, and disciplines in care team), and characteristics on the health-care provider level (caseload, training, and experience). We distinguished clinical outcome measures (HIV-RNA levels, mortality, AIDS events, CD4 cell counts, and other) and process outcome measures (cART exposure; hepatitis B and C, tuberculosis (TB), and cervical cancer screening; pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP) prophylaxis; vaccination for influenza and hepatitis B; and monitoring of CD4 cells and other). Finally, we extracted patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) and measures of adherence, retention in care, and care utilization.

Findings from the literature review were grouped into (1) structural characteristics; (2) quality of care outcome measures; and (3) reported associations between structural characteristics and the quality of care.

During the search process we found a big variation in health outcome measures. This complicated summarization and comparison of studies. We therefore performed a final selection and only evaluated associations among studies that measured virologic success, as this was the most consistently used outcome measure.

Results

Our search strategy identified 770 potentially relevant citations. Forty additional citations were identified through manual screening of the references. We excluded 751 citations after screening of titles and abstracts (not relevant, measured inpatient mortality, or had a study period in the pre-cART era). We retrieved 59 articles for full text screening. Subsequently, 31 articles were excluded because they were only descriptive or focused exclusively on interventions or patient characteristics.

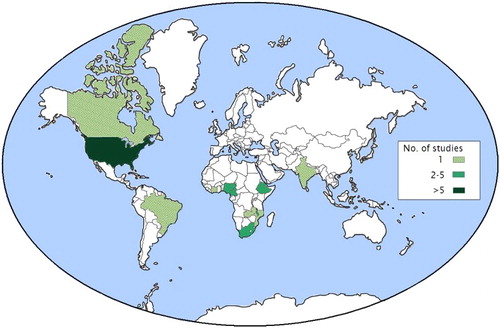

In total, 28 articles were included. The majority were retrospective cohort (n = 12) (Assefa et al., Citation2012; Backus et al., Citation2010; Chan et al., Citation2011; Chu, Umanski, Blank, Grossberg, & Selwyn, Citation2010; Fatti, Grimwood, & Bock, Citation2010; Kerr et al., Citation2012; Kitahata et al., Citation2003; Landon et al., Citation2005; Odafe, Idoko, et al., Citation2012; Odafe, Torpey, et al., Citation2012; Sherr et al., Citation2010; Solomon, Flynn, & Lavetsky, Citation2005) or cross-sectional studies (n = 7) (Anaya, Yano, & Asch, Citation2004; Boyer et al., Citation2011; Horberg, Hurley, Silverberg, Kinsman, & Quesenberry, Citation2007; Saha et al., Citation2013; Shet et al., Citation2011; Wilson, Landon, Ding, et al., Citation2005; Wilson, Landon, Hirschhorn, et al., Citation2005). One study had a prospective cohort design (Sangsari et al., Citation2012), and eight studies did not explicitly state their design strategy. Most of the studies had taken place in the USA (n = 12) (Anaya et al., Citation2004; Backus et al., Citation2010; Chu et al., Citation2010; Horberg et al., Citation2007; Kerr et al., Citation2012; Kitahata et al., Citation2003; Landon et al., Citation2005; Rodriguez, Marsden, Landon, Wilson, & Cleary, Citation2008; Saha et al., Citation2013; Solomon et al., Citation2005; Wilson, Landon, Ding, et al., Citation2005; Wilson, Landon, Hirschhorn, et al., Citation2005) and countries in sub-Saharan Africa (n = 13) (Assefa et al., Citation2012; Balcha & Jeppsson, Citation2010; Boyer et al., Citation2010, Citation2011; Chan et al., Citation2011; Ekouevi et al., Citation2012; Fatti et al., Citation2010; Fatti, Grimwood, Mothibi, & Shea, Citation2011; McGuire et al., Citation2012; Odafe, Idoko, et al., Citation2012; Odafe, Torpey, et al., Citation2012; Reidy et al., Citation2014; Sherr et al., Citation2010). The remaining studies were situated in Brazil (Nemes et al., Citation2009), India (Shet et al., Citation2011), and Canada (Sangsari et al., Citation2012) ().

Structural factors

The most commonly evaluated health facility characteristic () was number of HIV-infected patients in care (‘facility volume’, n = 7). Facility volume was generally defined as the number of HIV-infected patients in outpatient care. The number of categories and definitions varied: four categories: <25; 25–99; 100–299; and >300 patients (Backus et al., Citation2010); three categories: <15; 16–100; and 101–500 (Solomon et al., Citation2005) or <100; 100–500; and >500 patients (Nemes et al., Citation2009); and two categories: <950 and >950 patients (Fatti et al., Citation2011). The number of beds (Boyer et al., Citation2011) and number of outpatient visits per year (Wilson, Landon, Ding, et al., Citation2005) were also used to define facility volume.

Table 1. Summary of assessed structural characteristics (n = 28).

Other health facility characteristics of interest were specialization (Nemes et al., Citation2009; Wilson, Landon, Ding, et al., Citation2005) and team composition (Horberg et al., Citation2007; Rodriguez et al., Citation2008). Facilities that only treated patients with Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) and HIV infection (Nemes et al., Citation2009), or that were regarded as a “specialized HIV practice” (Wilson, Landon, Ding, et al., Citation2005) by the medical director, were defined as specialized facilities. Studies focusing on team composition assessed the presence of a clinical pharmacist with specialization in HIV disease (Horberg et al., Citation2007), and treatment team diversity (7 categories based on the number of disciplines) (Rodriguez et al., Citation2008).

Thirteen studies evaluated the setting of the health facility. These studies assessed the impact of private versus public funding (Boyer et al., Citation2011; Ekouevi et al., Citation2012; Shet et al., Citation2011), level of care (primary/secondary/tertiary; hospital/clinic; or centralized/decentralized) (Assefa et al., Citation2012; Balcha & Jeppsson, Citation2010; Boyer et al., Citation2010, Citation2011; Chan et al., Citation2011; Ekouevi et al., Citation2012; Fatti et al., Citation2010; McGuire et al., Citation2012; Odafe, Idoko, et al., Citation2012; Odafe, Torpey, et al., Citation2012; Reidy et al., Citation2014), and location of care site (urban/rural) (Anaya et al., Citation2004; Balcha & Jeppsson, Citation2010; Boyer et al., Citation2010; Ekouevi et al., Citation2012).

The most commonly evaluated health-care provider characteristic was HIV-specific specialization (n = 7). The studies generally compared the performance of infectious disease specialists versus expert generalists and non-expert generalists. In addition, the quality of care provided by non-physician clinicians (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) was assessed.

HIV-related experience was another commonly studied provider characteristic. Experience was expressed in terms of number of HIV-infected patients previously treated by, or the number of patients currently under the care of the health-care provider (provider HIV caseload).

One study assessed self-reported cultural competence (CC) of health-care providers (Saha et al., Citation2013). Interventions to improve CC (the ability to understand and respect values, attitudes, and beliefs that differ across cultures) have gained attention, particularly in high-income countries with diverse population groups (Horvat, Horey, Romios, & Kis-Rigo, Citation2014).

Measures of quality of care

shows that the most frequently used clinical outcome measures were virologic success (n = 11) and mortality (n = 9). Virologic success was generally defined as one undetectable HIV-RNA measurement with a threshold ranging from 50 to 500 copies/ml. A minority of studies looked at two consecutive measurements, or specified a time period after the initiation of cART. Other studies measured time to viral suppression. Mortality was assessed after a specific follow-up time (Balcha & Jeppsson, Citation2010; McGuire et al., Citation2012) or during the entire study period.

Table 2. Summary of assessed quality of care measures (n = 28).

Changes in mean CD4 cell count, average monthly gain, and the proportion of patients with CD4 cells <200 cells/µL were used to define immunological success. Additional clinical outcomes were side effects (clinical diagnosis related to first-line treatment) (Chan et al., Citation2011) and number of drug-resistant mutations (Shet et al., Citation2011).

The most common process measure was cART exposure among eligible patients (n = 9). cART eligibility depended on the guidelines used by the health facility. Time on cART was also used to measure quality of care.

One study assessed processes that are not directly HIV-related in the measurement of quality of care (Kerr et al., Citation2012). In this study, safety laboratory assessments were measured (≥3 complete blood count and serum creatinine measurements, and liver function tests). In addition, HIV-related primary care measures were included (annual lipid assessments, annual fasting glucose, and baseline hepatitis A, B, and C laboratory assessment).

One study used (unstandardized/unvalidated) PROMs to measure quality of care (Rodriguez et al., Citation2008). Patient satisfaction was measured with one question. Number of “unmet needs” (income assistance, housing, home health care, counseling, and drug/alcohol treatment), perceived access to care, and patient trust and willingness to recommend care were also assessed.

Retention in care was assessed by measuring loss to follow-up (LTFU, n = 9). Most of the studies defined LTFU as absence from treatment for at least 3 months after the last missed appointment date (Fatti et al., Citation2010, Citation2011; Odafe, Idoko, et al., Citation2012; Odafe, Torpey, et al., Citation2012). In two studies, failed attempts at tracking the patients was included in the definition of LTFU (Odafe, Idoko, et al., Citation2012; Odafe, Torpey, et al., Citation2012).

The two remaining outcomes were care utilization and adherence to cART. Adherence in the previous 3 or 4 days was measured with standardized questionnaires (Boyer et al., Citation2010, Citation2011; Saha et al., Citation2013). In two of these studies, treatment interruptions in the 4 preceding weeks were also assessed (Boyer et al., Citation2011, Citation2010). One study used pharmacy refill data in the 180 days after starting cART to measure adherence (Sherr et al., Citation2010).

Associations between structural factors and quality of care

A total of 11 studies were included in the assessment of structural characteristics associated with quality of HIV outpatient care (). Two of the studies showed an association between facility volume and the likelihood of achieving viral suppression. In the first study, patients from large facilities (>300 patients in care) were more likely to achieve viral suppression than patients from small facilities (Backus et al., Citation2010). In the second study, based in South Africa, rates of viral suppression were lower in large care sites (>950). This association only applied to the first 12 months after starting cART (Fatti et al., Citation2011).

Table 3. Summary of fully reviewed studies (n = 11).

In three studies, a positive association was found between physician expertise and virologic success. Two studies used a composite variable with three levels of expertise: infectious disease physicians, expert generalists, and non-expert generalists. Physicians were asked whether they considered themselves to be specialists in HIV (“experts”) (Landon et al., Citation2005; Wilson, Landon, Hirschhorn, et al., Citation2005). A significant association between current HIV caseload (an increase of 100 patients in care) and viral suppression was found in one study (Sangsari et al., Citation2012), and not found in another (categories: <19; 20–299; and >300 patients in care) (Landon et al., Citation2005). In one study assessing performance by non-physician clinicians, rates of viral suppression among patients treated by nurse practitioners and physician assistants were similar to those among patients treated by infectious disease-trained physicians and generalist HIV experts. Moreover, the rates of viral suppression among patients treated by non-physician clinicians were higher than those among patients treated by generalist non-HIV experts (Wilson, Landon, Hirschhorn, et al., Citation2005).

Four studies focused on health facility setting. There was no difference in virologic success among patients in care in centralized (hospital-based) versus decentralized (community-based) facilities (Chu et al., Citation2010; McGuire et al., Citation2012) (the USA and Malawi). In one study, patients treated in private health facilities were more likely to have treatment failure compared to patients in public/public–private health facilities (India) (Shet et al., Citation2011). This also applied to patients in district/regional hospitals versus primary health-care facilities (South Africa) (Fatti et al., Citation2010).

Finally, provider CC (assessment of cultural skills) (Saha et al., Citation2013) and the involvement of a clinical pharmacist in HIV outpatient care (Horberg et al., Citation2007) were positively associated with viral suppression.

Discussion

In this review, we evaluate the studies that have investigated the impact of health-care facility and care provider characteristics on health outcomes in HIV outpatient care. We point out a number of findings that are of particular importance when interpreting the results of the identified studies.

First, a disproportionate amount of studies is based in the USA and in countries in sub-Saharan Africa, making it difficult to generalize findings to other parts of the world (Figure 1).

Another important finding involves the diversity in choice and definition of structural variables across the different studies. This makes it difficult to summarize results and translate the results into practice.

A third key finding is the scope of measures of quality of care used in the studies. More than 20 outcomes were measured, with exact definitions often differing between studies (e.g., cART exposure and time on cART). Mortality was measured relatively often, evidently more often in low-resource countries. In contrast, screening of TB, hepatitis B and C, and cervical cancer was only assessed in the USA.

Interestingly, almost all of the studies only used measures that are directly related to HIV infection. Despite the fact that the importance of management of non-HIV comorbidities has been recognized (Chu et al., Citation2011), no studies measured non-HIV outcomes (e.g., blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose) and only one measured process outcomes related to comorbidity (Kerr et al., Citation2012).

Also surprising is the fact that only one study used PROMs. PROMs can help in gaining an insight into whether patients’ health-care experiences match their expectations. The importance of including patients' views when evaluating health care has been widely recognized. A positive physician/patient relationship may lead to better HIV treatment adherence and improved clinical outcomes (Land, Nixon, & Ross, Citation2011). PROMS can also be used to evaluate the impact of both disease and treatment as perceived by the patient, also referred to as health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (de Boer-van der Kolk et al., Citation2010). Evidence suggests that better HRQOL is associated with survival in HIV-infected patients (de Boer-van der Kolk et al., Citation2010; Cunningham, Crystal, Bozzette, & Hays, Citation2005).

Consistent with previous reviews with a similar focus (Handford, Rackal, Tynan, Rzeznikiewiz, & Glazier, Citation2012; Rackal et al., Citation2011), we found positive associations between health-care provider expertise and health outcomes among HIV-infected patients. However, our results regarding facility volume were less convincing than those in previously published reviews (Handford et al., Citation2012; Handford, Tynan, Rackal, & Glazier, Citation2006). These reviews differ in the sense that they included many studies that took place before the introduction of cART. Furthermore, in-hospital mortality was often measured, whereas our review focusses on outpatient care.

For our assessment of the results of the studies, we only selected the studies that measured viral suppression. We did this for the sake of comparability of studies but are aware of the fact that we have not presented associations with other outcomes of care. We do, however, believe that HIV-RNA measurement is an appropriate quality of care measurement, more so perhaps than mortality (in this post-cART era) and CD4 cell count.

Implications for practice

Our findings suggest that health-care provider experience improves outcomes among HIV-infected patients. Additional research is needed to specify the number of patients required to gain and maintain expertise. We cannot make recommendations regarding facility volume requirements for outpatient care on the basis of the identified studies (Backus et al., Citation2010; Fatti et al., Citation2011). The studies took place in very different settings (the USA and South Africa), used different definitions of large hospitals (>300 and >950), and had contrasting results. The increased probability of virologic failure at large clinics in the South Africa-based study could be explained by heavy workloads, strain on the hospital infrastructure, and longer waiting times (Mugavero et al., Citation2007).

The study by Wilson et al., in which the quality of care by non-physician clinicians was evaluated, provides additional support for the effectiveness of task shifting (Wilson, Landon, Hirschhorn, et al., Citation2005). Task shifting is the assigning of particular tasks to health-care workers with shorter training and fewer qualifications (e.g., cART prescription by nurses). This model of care can result in substantial cost savings and has been recommended as an approach to reduce resource shortages in low-income countries (WHO, Citation2008). Reviews on task shifting are available (Callaghan et al., Citation2010; Kredo et al., Citation2014; Mdege et al., Citation2013).

Only one study evaluated the involvement of disciplines other than physicians, non-physician clinicians, or nurses (Horberg et al., Citation2007). The results support the involvement of a clinical pharmacist in HIV outpatient care. More evidence regarding this issue can be found in the review article by Saberi et al. (Saberi, Dong, Johnson, Greenblatt, & Cocohoba, Citation2012).

Implications for research

Research needs to be extended to regions outside the USA and sub-Saharan Africa. Existing cohort studies may create opportunities to expand this research field. In Europe for example, there are multiple cohort studies (Mary-Krause et al., Citation2014; Omland, Ahlstrom, & Obel, Citation2014; Schoeni-Affolter et al., Citation2010; van Sighem, Smit, Stolte, & Reiss, Citation2014), some of which participate in collaborations with other cohort studies (Bohlius et al., Citation2009; May et al., Citation2014). The collected data can be an excellent source for retrospective research into the impact of health facility characteristics (such as facility volume) on health outcomes.

Furthermore, researchers should align their methods of measuring quality of care. An initial step in this process is to define what good quality of HIV care is (Hung & Pradel, Citation2014). Since the role of non-HIV comorbidity is increasing, researchers and health-care providers need to go beyond HIV-related morbidity in the evaluation of health outcomes (Chu et al., Citation2011).

As retention in care has been recognized as a crucial step in maximizing patient outcomes, we believe it should continue to be measured in quality of care studies. Mugavero et al. present a number of released core indicators for retention in care (Citation2012). In addition, patient preferences and satisfaction should play an important role in the evaluation of quality of care. In a systematic review, Land et al. provide an overview of methods for measuring patient satisfaction in HIV care delivery (Land et al., Citation2011). The authors concluded that there is no gold standard, and findings were used to develop a validated questionnaire (Land, Sizmur, Harding, & Ross, Citation2013).

There are several sources for HIV-related measures, including the article by Catumbela et al., in which the authors propose a core set of HIV-related quality of care measures based on a literature review (Citation2013).

In conclusion, the studies that demonstrate associations between the quality of HIV outpatient care and facility and care provider characteristics are not scarce, but too diverse and inconsistent to guide policy regarding standards of care. Important reasons for this are the heterogeneity of study designs and the underrepresentation of studies outside the USA and sub-Saharan Africa. Patient views and non-HIV comorbidities should be included in the assessment of quality of HIV outpatient care in future studies.

Acknowledgements

E.A.N.E. collected all data and drafted the article. All authors edited, commented, and approved the final version of the article.

P.R. through his institution has received independent scientific grant support from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Merck & Co, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS). In addition, he serves on a scientific advisory board for Gilead Sciences and on a data and safety monitoring board for Janssen Pharmaceutica, for which his institution has received remunerations. K.B. serves on advisory boards for MSD, Gilead, BMS, Viiv, and Janssen for which he has received remuneration. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anaya, H. D., Yano, E. M., & Asch, S. M. (2004). Early adoption of human immunodeficiency virus quality improvement in Veterans Affairs Medical Centers: Use of organizational surveys to measure readiness to change and adapt interventions to local priorities. American Journal of Medical Quality, 19(4), 137–144. doi: 10.1177/106286060401900402

- Assefa, Y., Kiflie, A., Tekle, B., Mariam, D. H., Laga, M., & Van Damme, W. (2012). Effectiveness and acceptability of delivery of antiretroviral treatment in health centres by health officers and nurses in Ethiopia. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 17(1), 24–29. doi:10.1258/jhsrp.2011.010135

- Backus, L. I., Boothroyd, D. B., Phillips, B. R., Belperio, P. S., Halloran, J. P., Valdiserri, R. O., & Mole, L. A. (2010). National quality forum performance measures for HIV/AIDS care: The Department of Veterans Affairs’ experience. Archives of Internal Medicine, 170(14), 1239–1246. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.234

- Balcha, T. T., & Jeppsson, A. (2010). Outcomes of antiretroviral treatment: a comparison between hospitals and health centers in Ethiopia. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care (JIAPAC), 9(5), 318–324. doi:10.1177/1545109710367518

- Bennett, C. L., Adams, J., Bennett, R. L., Rodrique, D., George, L., Cassileth, B., & Gilman, S. C. (1995). The learning curve for AIDS-related Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia: Experience from 3,981 cases in Veterans Affairs Hospitals 1987–1991. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes & Human Retrovirology, 8(4), 373–378. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199504000-00008

- Bennett, C. L., Adams, J., Gertler, P., Park, R. E., Gilman, S., George, L., … Brook, R. H. (1992). Relation between hospital experience and in-hospital mortality for patients with AIDS-related Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia: experience from 3,126 cases in New York City in 1987. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 5(9), 856–864.

- Bennett, C. L., Garfinkle, J. B., Greenfield, S., Draper, D., Rogers, W., Mathews, C., & Kanouse, D. E. (1989). The relation between hospital experience and in-hospital mortality for patients with AIDS-related PCP. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 261(20), 2975–2979. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03420200065039

- de Boer-van der Kolk, I. M., Sprangers, M. A., Prins, J. M., Smit, C., de Wolf, F., & Nieuwkerk, P. T. (2010). Health-related quality of life and survival among HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy: a study of patients in the AIDS Therapy Evaluation in the Netherlands (ATHENA) Cohort. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 50(2), 255–263. doi:10.1086/649216

- Bohlius, J., Schmidlin, K., Costagliola, D., Fatkenheuer, G., May, M., Caro-Murillo, A. M., … Egger, M. (2009). Incidence and risk factors of HIV-related non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: A European multicohort study. Antiviral Therapy, 14(8), 1065–1074. doi:10.3851/imp1462

- Boyer, S., Clerc, I., Bonono, C. R., Marcellin, F., Bile, P. C., & Ventelou, B. (2011). Non-adherence to antiretroviral treatment and unplanned treatment interruption among people living with HIV/AIDS in Cameroon: Individual and healthcare supply-related factors. Social Science & Medicine, 72(8), 1383–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.030

- Boyer, S., Eboko, F., Camara, M., Abe, C., Nguini, M. E., Koulla-Shiro, S., & Moatti, J. P. (2010). Scaling up access to antiretroviral treatment for HIV infection: the impact of decentralization of healthcare delivery in Cameroon. AIDS, 24(Suppl. 1), S5–S15. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000366078.45451.46

- Callaghan, M., Ford, N., & Schneider, H. (2010). A systematic review of task-shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Human Resources for Health, 8, 8. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-8-8

- Catumbela, E., Certal, V., Freitas, A., Costa, C., Sarmento, A., & da Costa Pereira, A. (2013). Definition of a core set of quality indicators for the assessment of HIV/AIDS clinical care: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 236. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-236

- Chan, A. K., van Lettow, M., Tenthani, L., Kumwenda, M., Gawa, L., Kadzanja, A., … Kambanji, M. (2011). Outcome assessment of a dedicated HIV positive health care worker clinic at a central hospital in Malawi: A retrospective observational study. PLoS One, 6(5), e19789. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019789

- Chu, C., Umanski, G., Blank, A., Grossberg, R., & Selwyn, P. A. (2010). HIV-infected patients and treatment outcomes: an equivalence study of community-located, primary care-based HIV treatment vs. hospital-based specialty care in the Bronx, New York. AIDS Care, 22(12), 1522–1529. doi:10.1080/09540121.2010.484456

- Chu, C., Umanski, G., Blank, A., Meissner, P., Grossberg, R., & Selwyn, P. A. (2011). Comorbidity-related treatment outcomes among HIV-infected adults in the Bronx, NY. Journal of Urban Health, 88(3), 507–516. doi:10.1007/s11524-010-9540-7

- Cunningham, W. E., Crystal, S., Bozzette, S., & Hays, R. D. (2005). The association of health-related quality of life with survival among persons with HIV infection in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(1), 21–27. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.30402.x

- Cunningham, W. E., Tisnado, D. M., Lui, H. H., Nakazono, T. T., & Carlisle, D. M. (1999). The effect of hospital experience on mortality among patients hospitalized with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in California. The American Journal of Medicine, 107(2), 137–143. doi: S0002934399001953 [pii]

- Donabedian, A. (1988). The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA, 260(12), 1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.1988.03410120089033

- Ekouevi, D. K., Stringer, E., Coetzee, D., Tih, P., Creek, T., Stinson, K., … Dabis, F. (2012). Health facility characteristics and their relationship to coverage of PMTCT of HIV services across four African countries: The PEARL study. PLoS One, 7(1), e29823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029823

- Fatti, G., Grimwood, A., & Bock, P. (2010). Better antiretroviral therapy outcomes at primary healthcare facilities: An evaluation of three tiers of ART services in four South African provinces. PLoS One, 5(9), e12888. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012888

- Fatti, G., Grimwood, A., Mothibi, E., & Shea, J. (2011). The effect of patient load on antiretroviral treatment programmatic outcomes at primary health care facilities in South Africa: A multicohort study. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 58(1), e17–e19. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e318229baab

- Handford, C. D., Rackal, J. M., Tynan, A. M., Rzeznikiewiz, D., & Glazier, R. H. (2012). The association of hospital, clinic and provider volume with HIV/AIDS care and mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care, 24(3), 267–282. doi:10.1080/09540121.2011.608419

- Handford, C. D., Tynan, A. M., Rackal, J. M., & Glazier, R. H. (2006). Setting and organization of care for persons living with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, 2006(3), CD004348. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004348.pub2

- Hecht, F. M., Wilson, I. B., Wu, A. W., Cook, R. L., & Turner, B. J. (1999). Optimizing care for persons with HIV infection. Society of General Internal Medicine AIDS Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine, 131(2), 136–143. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-2-199907200-00011

- Hogg, R. S., Raboud, J., Bigham, M., Montaner, J. S., O'Shaughnessy, M., & Schechter, M. T. (1998). Relation between hospital HIV/AIDS caseload and mortality among persons with HIV/AIDS in Canada. Clinical Investigation Medicine, 21(1), 27–32.

- Horberg, M. A., Hurley, L. B., Silverberg, M. J., Kinsman, C. J., & Quesenberry, C. P. (2007). Effect of clinical pharmacists on utilization of and clinical response to antiretroviral therapy. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 44(5), 531–539. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e318031d7cd

- Horvat, L., Horey, D., Romios, P., & Kis-Rigo, J. (2014). Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, 5, Cd009405. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009405.pub2

- Hung, A., & Pradel, F. (2014). A review of how the quality of HIV clinical services has been evaluated or improved. International Journal of STD AIDS, 26(7), 445–455. doi:10.1177/0956462414543938

- Kerr, C. A., Neeman, N., Davis, R. B., Schulze, J., Libman, H., Markson, L., … Bell, S. K. (2012). HIV Quality of Care Assessment at an Academic Hospital: Outcomes and lessons learned. American Journal of Medical Quality. doi: 1062860611425714 [pii]

- Kitahata, M. M., Koepsell, T. D., Deyo, R. A., Maxwell, C. L., Dodge, W. T., & Wagner, E. H. (1996). Physicians’ experience with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome as a factor in patients’ survival. New England Journal of Medicine, 334(11), 701–706. doi:10.1056/nejm199603143341106

- Kitahata, M. M., Rompaey, S. E., Dillingham, P. W., Koepsell, T. D., Deyo, R. A., Dodge, W., & Wagner, E. H. (2003). Primary care delivery is associated with greater physician experience and improved survival among persons with AIDS. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 18(2), 95–103. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.11049.x

- Kredo, T., Adeniyi, F. B., Bateganya, M., & Pienaar, E. D. (2014). Task shifting from doctors to non-doctors for initiation and maintenance of antiretroviral therapy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, 7, Cd007331. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007331.pub3

- Laine, C., Markson, L. E., McKee, L. J., Hauck, W. W., Fanning, T. R., & Turner, B. J. (1998). The relationship of clinic experience with advanced HIV and survival of women with AIDS. AIDS, 12(4), 417–424. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199804000-00011

- Land, L., Nixon, S., & Ross, J. D. (2011). Patient-derived outcome measures for HIV services in the developed world: a systematic review. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 22(8), 430–435. doi:10.1258/ijsa.2011.010450

- Land, L., Sizmur, S., Harding, J., & Ross, J. D. (2013). Development of a validated patient satisfaction survey for HIV clinic attendees. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 24(3), 201–209. doi:10.1177/0956462412472447

- Landon, B. E., Wilson, I. B., Cohn, S. E., Fichtenbaum, C. J., Wong, M. D., Wenger, N. S., … Cleary, P. D. (2003). Physician specialization and antiretroviral therapy for HIV: Adoption and use in a national probability sample of persons infected with HIV. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 18(4), 233–241. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20705.x

- Landon, B. E., Wilson, I. B., McInnes, K., Landrum, M. B., Hirschhorn, L. R., Marsden, P. V., & Cleary, P. D. (2005). Physician specialization and the quality of care for human immunodeficiency virus infection. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(10), 1133–1139. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.10.1133

- Lazarus, J. V., Safreed-Harmon, K., Nicholson, J., & Jaffar, S. (2014). Health service delivery models for the provision of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 19(10), 1198–1215. doi:10.1111/tmi.12366

- Mary-Krause, M., Grabar, S., Lievre, L., Abgrall, S., Billaud, E., Boue, F., … Costagliola, D. (2014). Cohort Profile: French hospital database on HIV (FHDH-ANRS CO4). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(5), 1425–1436. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu002

- May, M. T., Ingle, S. M., Costagliola, D., Justice, A. C., de Wolf, F., Cavassini, M., … Sterne, J. A. (2014). Cohort profile: Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration (ART-CC). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(3), 691–702. doi:10.1093/ije/dyt010

- McGuire, M., Pinoges, L., Kanapathipillai, R., Munyenyembe, T., Huckabee, M., Makombe, S., … Pujades-Rodriguez, M. (2012). Treatment initiation, program attrition and patient treatment outcomes associated with scale-up and decentralization of HIV care in rural Malawi. PLoS One, 7(10), e38044. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038044

- Mdege, N. D., Chindove, S., & Ali, S. (2013). The effectiveness and cost implications of task-shifting in the delivery of antiretroviral therapy to HIV-infected patients: a systematic review. Health Policy and Planning, 28(3), 223–236. doi:10.1093/heapol/czs058

- Mugavero, M. J., Lin, H. Y., Allison, J. J., Willig, J. H., Chang, P. W., Marler, M., … Saag, M. S. (2007). Failure to establish HIV care: Characterizing the “no show” phenomenon. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 45(1), 127–130. doi:10.1086/518587

- Mugavero, M. J., Westfall, A. O., Zinski, A., Davila, J., Drainoni, M. L., Gardner, L. I., … Giordano, T. P. (2012). Measuring retention in HIV care: the elusive gold standard. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 61(5), 574–580. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e318273762f

- Nemes, M. I., Melchior, R., Basso, C. R., Castanheira, E. R., de Britto e Alves, M. T., & Conway, S. (2009). The variability and predictors of quality of AIDS care services in Brazil. BMC Health Services Research, 9, 51. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-9-51

- Odafe, S., Idoko, O., Badru, T., Aiyenigba, B., Suzuki, C., Khamofu, H., … Chabikuli, O. N. (2012). Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics and level of care associated with lost to follow-up and mortality in adult patients on first-line ART in Nigerian hospitals. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 15(2), 17424. doi:10.7448/ias.15.2.17424

- Odafe, S., Torpey, K., Khamofu, H., Ogbanufe, O., Oladele, E. A., Kuti, O., … Chabikuli, O. (2012). The pattern of attrition from an antiretroviral treatment program in Nigeria. PLoS One, 7(12), e51254. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051254

- Omland, L. H., Ahlstrom, M. G., & Obel, N. (2014). Cohort profile update: The Danish HIV cohort study (DHCS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(6), 1769–1769e. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu153

- Rackal, J. M., Tynan, A. M., Handford, C. D., Rzeznikiewiz, D., Agha, A., & Glazier, R. (2011). Provider training and experience for people living with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, 2011(6), CD003938. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003938.pub2

- Reidy, W. J., Sheriff, M., Wang, C., Hawken, M., Koech, E., Elul, B., … Abrams, E. J. (2014). Decentralization of HIV care and treatment services in Central Province, Kenya. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 67(1), e34–e40. doi:10.1097/qai.0000000000000264

- Rodriguez, H. P., Marsden, P. V., Landon, B. E., Wilson, I. B., & Cleary, P. D. (2008). The effect of care team composition on the quality of HIV care. Medical Care Research and Review, 65(1), 88–113. doi:10.1177/1077558707310258

- Saberi, P., Dong, B. J., Johnson, M. O., Greenblatt, R. M., & Cocohoba, J. M. (2012). The impact of HIV clinical pharmacists on HIV treatment outcomes: A systematic review. Patient Preference and Adherence, 6, 297–322. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S30244

- Saha, S., Korthuis, P. T., Cohn, J. A., Sharp, V. L., Moore, R. D., & Beach, M. C. (2013). Primary care provider cultural competence and racial disparities in HIV care and outcomes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(5), 622–629. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2298-8

- Sangsari, S., Milloy, M. J., Ibrahim, A., Kerr, T., Zhang, R., Montaner, J., & Wood, E. (2012). Physician experience and rates of plasma HIV-1 RNA suppression among illicit drug users: An observational study. BMC Infectious Disease, 12(22). doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-22

- Schoeni-Affolter, F., Ledergerber, B., Rickenbach, M., Rudin, C., Gunthard, H. F., Telenti, A., … Francioli, P. (2010). Cohort profile: The Swiss HIV cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 39(5), 1179–1189. doi:10.1093/ije/dyp321

- Sherr, K. H., Micek, M. A., Gimbel, S. O., Gloyd, S. S., Hughes, J. P., John-Stewart, G. C., … Weiss, N. S. (2010). Quality of HIV care provided by non-physician clinicians and physicians in Mozambique: A retrospective cohort study. AIDS, 24(Suppl. 1), S59–S66. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000366083.75945.07

- Shet, A., DeCosta, A., Heylen, E., Shastri, S., Chandy, S., & Ekstrand, M. (2011). High rates of adherence and treatment success in a public and public-private HIV clinic in India: Potential benefits of standardized national care delivery systems. BMC Health Services Research, 11, 277. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-277

- van Sighem, A. G. L., Smit, C., Stolte, I., & Reiss, P. (2014). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in the Netherlands. Monitoring report 2014. Retrieved from http://www.hiv-monitoring.nl/files/8914/1527/1076/SHM_Monitoring_report_2014.pdf.

- Solomon, L., Flynn, C., & Lavetsky, G. (2005). Managed care for AIDS patients: is bigger better? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 38(3), 342–347.

- Soto, T. A., Bell, J., & Pillen, M. B. For the HIV/AIDS treatment adherence, health outcomes cost study group. (2004). Literature on integrated HIV care: A review. AIDS Care, 16(Suppl. 1), S43–S55. doi:10.1080/09540120412331315295

- Stone, V. E., Seage, G. R.3rd, Hertz, T., & Epstein, A. M. (1992). The relation between hospital experience and mortality for patients with AIDS. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 268(19), 2655–2661. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490190055031

- Thompson, M. A., Mugavero, M. J., Amico, K. R., Cargill, V. A., Chang, L. W., Gross, R., … Nachega, J. B. (2012). Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: Evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS care panel. Annals of Internal Medicine, 156(11), 817–833. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00419

- Turner, B. J., & Ball, J. K. (1992). Variations in inpatient mortality for AIDS in a national sample of hospitals. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 5(10), 978–987.

- WHO. (2008). Task shifting: Rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams: Global recommendations and guidelines. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/healthsystems/TTR-TaskShifting.pdf

- Wilson, I. B., Landon, B. E., Ding, L., Zaslavsky, A. M., Shapiro, M. F., Bozzette, S. A., & Cleary, P. D. (2005). A national study of the relationship of care site HIV specialization to early adoption of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Medical Care, 43(1), 12–20. doi: 00005650-200501000-00003 [pii]

- Wilson, I. B., Landon, B. E., Hirschhorn, L. R., McInnes, K., Ding, L., Marsden, P. V., & Cleary, P. D. (2005). Quality of HIV care provided by nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 143(10), 729–736. doi: 143/10/729 [pii]