ABSTRACT

In the context of the ANRS 12249 Treatment as Prevention (TasP) trial, we investigated perceptions of regular and repeat HIV-testing in rural KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa), an area of very high HIV prevalence and incidence. We conducted two qualitative studies, before (2010) and during the early implementation stages of the trial (2013–2014), to appreciate the evolution in community perceptions of repeat HIV-testing over this period of rapid changes in HIV-testing and treatment approaches. Repeated focus group discussions were organized with young adults, older adults and mixed groups. Repeat and regular HIV-testing was overall well perceived before, and well received during, trial implementation. Yet community members were not able to articulate reasons why people might want to test regularly or repeatedly, apart from individual sexual risk-taking. Repeat home-based HIV-testing was considered as feasible and convenient, and described as more acceptable than clinic-based HIV-testing, mostly because of privacy and confidentiality. However, socially regulated discourses around appropriate sexual behaviour and perceptions of stigma and prejudice regarding HIV and sexual risk-taking were consistently reported. This study suggests several avenues to improve HIV-testing acceptability, including implementing diverse and personalised approaches to HIV-testing and care, and providing opportunities for antiretroviral therapy initiation and care at home.

Introduction

HIV-testing is a critical intermediate step on the prevention pathway (Shelton, Citation2008). Accurate knowledge of one’s own HIV status is a prerequisite to being able to access and effectively use HIV prevention and treatment interventions. Regular and repeat testing facilitates early identification of new HIV infections and provides an opportunity to extend early treatment access. Early modelling studies aiming to estimate the potential impact of universal test and treat (UTT) strategies were based on universal acceptance of annual HIV-testing (Granich, Gilks, Dye, De Cock, & Williams, Citation2009), but it remains unclear whether this can be achieved and sustained. Improvements in HIV-testing coverage and acceptance of community-based testing services have been documented worldwide (Suthar et al., Citation2013; World Health Organisation, Citation2014), but in 2013 it was still estimated that 55% of people with HIV remained unaware of their status, and testing continues to be delivered “without specifically aiming to reach those most at risk and as yet undiagnosed” (World Health Organisation, Citation2015a).

The literature on uptake of repeat HIV-testing is limited, and reported rates of repeat testing range from 26% in two South African hospitals (Regan et al., Citation2013), 43% between consecutive rounds of testing provided during serological surveillance in Kisesa (Tanzania) (Cawley et al., Citation2013), to 87% among women and 79% among men in repeated home-based HIV-testing campaigns in rural Malawi (Helleringer, Mkandawire, Reniers, Kalilani-Phiri, & Kohler, Citation2013).

Acceptance of HIV-testing in many contexts remains constrained by poor self-assessment of HIV risk (Corneli et al., Citation2014; Prata, Morris, Mazive, Vahidnia, & Stehr, Citation2006), fear of a positive test result and the potential follow-on consequences – stigma and discrimination, physical incapacity and perceived likelihood of death (Denison, McCauley, Dunnett-Dagg, Lungu, & Sweat, Citation2008). The impact of an HIV test on expectations and engagement in prevention behaviours is complex (Delavande & Kohler, Citation2012). Among the documented barriers specific to repeat HIV-testing are population mobility (Obare et al., Citation2009) and belief that a negative HIV test result is permanent (Ryder et al., Citation2005), while specific facilitators include knowing someone living with HIV (Regan et al., Citation2013). Studies have reported that repeat HIV-negative testers are less likely than first-time testers to reduce their sexual risk behaviours following an HIV test (Matovu et al., Citation2007; Ryder et al., Citation2005), suggesting poor individual and community understanding of the benefits of repeat HIV-testing.

International antiretroviral treatment eligibility criteria have broadened over the past 10 years as evidence has accumulated regarding the clinical and preventive benefits of early treatment initiation. As of July 2015, WHO recommends that immediate ART should be offered to all individuals diagnosed with HIV regardless of their CD4 count and clinical staging (World Health Organisation, Citation2015b).

Five large UTT studies are currently underway in sub-Saharan Africa to evaluate the field efficacy of a universal offer of HIV-testing, followed by an offer of immediate ART initiation to individuals ascertained to be HIV-infected. These trials raise numerous questions about the different components of the intervention package, including models of repeat HIV-testing delivery. How do community members understand and accept regular and repeated door-to-door offers of HIV-testing? Does the context of very rapid changes in treatment approaches influence perceptions and engagement with repeat HIV-testing? What social norms would require changes in order to foster more community support towards regular and repeat HIV-testing?

We investigated perceptions of repeat HIV-testing among rural communities in South Africa before and during the early implementation stages of the ANRS 12249 Treatment as Prevention (TasP) trial, that is, over a period of rapid changes in HIV treatment approaches.

Methods

The TasP trial setting

The TasP trial is being implemented in the Hlabisa sub-district, in northeast KwaZulu-Natal. This is a poor and predominantly rural area with approximately 228,000 Zulu-speaking inhabitants. An estimated 29% of adults (15–49 years) in the area are infected with HIV (Zaidi, Grapsa, Tanser, Newell, & Barnighausen, Citation2013). The Hlabisa HIV treatment and care programme, initiated in 2004, is decentralised in the 17 primary health-care clinics. People can access HIV-testing and counselling at any time and those eligible according to South African Department of Health guidelines receive free ART: by July 2011, an estimated 37% of all HIV-positive adults in the area had been successfully started on ART (Tanser, Barnighausen, Grapsa, Zaidi, & Newell, Citation2013). Life expectancy has dramatically improved since the early 2000 (Bor, Herbst, Newell, & Barnighausen, Citation2013); HIV incidence has decreased, but remains high in the area (Tanser et al., Citation2013).

Tasp trial summary

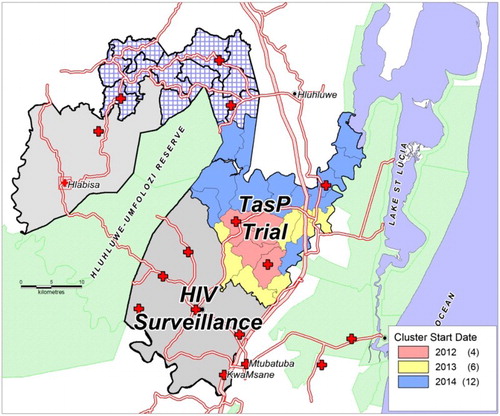

The TasP trial is a cluster-randomised trial coordinated by an international study group at the Africa Centre for Population Health, a research centre that has operated in the area for nearly 20 years. The trial has implemented universal and repeat home-based HIV-testing of all resident adults as standard of care, that is, in both study arms, and immediate ART initiation is implemented as the intervention (Box 1). Implementation of the trial has followed a phased approach: four clusters started in March 2012 (2 × 2), followed by six more clusters in January 2013 (2 × 3), and 12 more clusters in June 2014 (2 × 6). Follow-up is planned to continue in all clusters until June 2016 (Iwuji et al., Citation2013).

TEST

In both trial arms, rounds of home-based HIV-testing are repeated every six months. Households are approached by a team of trial community testers, all of whom are trained HIV counsellors. Permission is sought of the household head to offer HIV counselling and testing to adult members of the household. Individuals providing written informed consent to HIV-testing receive HIV counselling privately and confidentially, and rapid HIV-testing (test results provided approximately 20 min after testing).

TREAT

All individuals identified as HIV-positive are referred to a local TasP trial clinic (provision of HIV services, staffed by a counsellor and a nurse) situated in the trial cluster in which they live. In the control clusters, HIV-positive adults are offered ART according to current South African guidelines (i.e. at less than 350 CD4 cells/mm3 or WHO stage 3 or 4 or pregnancy until December 2014 and at less than 500 CD4 cells/mm3 since January 2015). In the intervention clusters, all HIV-positive adults seen in TasP trial clinics are offered the opportunity to begin ART immediately regardless of CD4 count or clinical staging.

Timeline

The first qualitative sub-study reported here (Pre-TasP research) was implemented between June and December 2010 prior the TasP trial implementation, in one of the four initial trial clusters selected at random. The second qualitative sub-study (TasP research) was conducted between January 2013 and July 2014, a few months after the TasP trial started, and in all four initial trial clusters (); it was part of a multidisciplinary, multi-level, mixed-methods research programme embedded within the trial (Orne-Gliemann et al., Citation2015); at that time, two rounds of home-based HIV-testing had taken place.

Study design

Both sub-studies referred to in this paper have used qualitative research techniques, specifically focus group discussions (FGD) and participant observation. FGDs provided collective perceptions of issues relating to repeat and regular HIV-testing, allowed culturally significant responses and stimulated free thought among participants (Geer, Citation1991; Kitzinger, Citation1995). The FGD groups were mixed gender and predefined into age categories (groups with younger or older adults only in the control clusters; and mixed age groups in the intervention clusters) to maximise data source variations. FGDs were repeated with the same participants to determine whether participants’ perceptions/experiences regarding regular and repeat HIV-testing changed or remained the same over time.

Study population and sample

Purposive and snowball recruitment techniques were used to identify and engage potential participants from the community. In the Pre-TasP research, 22 individuals participated in younger adults and mixed FGDs. In the TasP research, 42 individuals aged 19–70 were enrolled in the younger adults, older adults and mixed FGDs. Participants’ HIV status was unknown unless it had, without solicitation, been disclosed during an interview. Each group comprised between 9 and 16 individuals and met on several occasions with the same facilitator – twice for the Pre-TasP groups, four times for the TasP groups – for an average of 70 minutes (range 45–120 minutes). presents an overview of the main topics addressed within each FGD session as well as participant attendance and age data.

Table 1. Overview of FGD (content and participants) within the pre-TasP and TasP research. ANRS 12249 TasP trial.

Data collection

Pre-TasP group discussions were held at a community church. TasP group discussions were held in community venues organised with help from the local izinDuna (headmen). All FGD sessions were conducted by the same facilitator, using structured discussion guides, which were confirmed by the Africa Centre Community Advisory Board and Community Engagement Unit for language appropriateness. FGDs were conducted in Zulu and audio recorded with participants’ written informed consent. Transcription of recordings and translation from Zulu to English were performed by a translating panel (two individuals), and translations were validated by one of the authors.

Ethics

The Pre-TasP research was approved by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Human and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (HSS/0159/10). The TasP research was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, as part of the overall TasP trial (BCF104/11) and specifically the social science programme (BE090/12).

Analysis process

An inductive approach based on descriptive thematic coding was used. All transcripts were entered into qualitative data analysis software (NVivo version 10). Codebooks were developed using an iterative process: initial codes matched the predefined research themes, then were expanded with codes reflecting the participants’ own terms and semantics, and discussed among the researchers for triangulated input; codes were finally refined and augmented through manual coding of a selected number of FGDs.

The results are presented according to three main themes, which emerged through the discussion relating to: understanding of repeat HIV-testing, motives to repeat test, and models of repeat HIV-testing.

Results

Motivation to repeat test

At both time-points, HIV-testing was considered by most participants as a “good thing to do”. Pre-TasP groups explained HIV-testing was important in order to feel “free” (or to take away the burden of not knowing one’s status) and stay “alive” and healthy (make informed decisions on one’s health including accessing ART).

Certain Pre-TasP group participants supported the general idea of repeat and regular testing.

Pre-TasP group youth (S1): My suggestion is that it is important that you test all the time and once you have tested you should start treatment so that you can live for a long time. (female, unemployed, 30s)

However, repeated testing after testing HIV-negative was mostly perceived as unnecessary by Pre-TasP group participants. They explained that if these people were feeling healthy, they would assume their HIV-negative status had not changed, regardless of how long it had been since their last test.

Pre-TasP group mixed (S1): When they had said that I do not have it (HIV) what should I go back for? Yes it was just that and nothing else. Not that I became lazy or what maybe no, I just saw they said I do not have (HIV) so there was no reason for me to go back. (male, self-employed, 60s)

Pre-TasP group participants felt that someone needed to have a valid reason to constantly test for HIV: either because they perceived a risk related to their misbehaviour (having more than one sexual partner) or because there was something wrong with their health.

TasP group participants also expressed views that HIV-testing and repeat HIV-testing were associated with risk perception.

TasP group youth (S2): It may happen that you go for a test out of suspicion, … maybe if your partner is having multiple sexual relationships. You can also go for a test if your partner is involved with someone you once saw visiting there (ART clinic). [ … ] In that case people do go and test, to see if they are not infected if they suspect that they may be because of what is happening in their relationships. (male, unemployed, 27)

But TasP group participants also explained that regular testing allowed an accurate knowledge of one’s HIV status. Every three months was considered the optimal frequency to test for HIV.

TasP group youth (S3): It is important to test regularly maybe after 3 months because you may test negative now and may test positive on your second test. It is very helpful to test regularly than testing once only. (female, domestic worker, 21)

Models of repeat testing

Most Pre-TasP group participants identified clinics as good places to test for HIV. However, they also reported fear associated with gossip from health staff and community members if testing in local clinics. Pre-TasP group participants did not perceive clinic counsellors as reliable sources of support, as they were often busy or relocated and people could not count on seeing the same person at each visit. Transport could also be a barrier for those who lived far away from the clinic and so mobile clinics or home visits could make HIV-testing more accessible.

The majority of TasP group participants expressed reluctance to seek clinic-based testing, articulating concern about confidentiality and fear clinic staff might expose one’s HIV status and the fact that clinic-based HIV-testing was associated with an HIV-positive result.

TasP group older (S2): I also agree that testing at home is easier. There will be no friends or neighbours but only family members during the visit. They [youth] are scared to visit the clinic for HIV-testing because people will notice them when going to the park homes. They will gossip and assume that by entering the park homes, you are infected with HIV. Friends will not see when you are visited at your home. Most people die because they are scared to visit the clinic. People can laugh at you, but this is your health and you are willing to get better and be healthy. They are not scared when visited at home because there will be no friends and you will be sitting inside the room alone. (female, unemployed, 53)

At both time-points, home-based HIV-testing was considered as feasible and convenient, and consistently described as better and more acceptable than clinic-based testing; mostly because of privacy and confidentiality, but also because of its form of social support.

Pre TasP group youth (S2): But it is better because they [other community members] will not know why she [counsellor] comes to my home (participants laugh). That is not a problem because she will not be known here; even assuming such things [that she is here to do an HIV test] would be difficult for others to do, you see? (male, unemployed, 20s)

TasP group youth (S2): I think it is good to test at home than going to the clinic because it may happen that you have never thought about going for a test before. They will then explain more about the virus and you will finally understand and decide to get tested. I consider home based testing as the best option. (female, part-time domestic worker, 21)

TasP group participants from the intervention clusters also underlined that if diagnosed HIV-infected after repeat testing, one could initiate ART early. They also suggested that repeat home-based HIV-testing visits should include the opportunity for ART clinical assessment and initiation.

TasP group mixed (S2): When they come to test me they must bring treatment along. They test me at home, so treatment should also be brought to me at home. (female, unemployed, age unknown)

TasP group mixed (S2): They will do other tests at home after they have done the HIV test. Are they just only able to do the HIV test? They can do other tests as well. (female, unemployed, age unknown)

Discussion

Universal testing and early access to ART provide opportunities to accelerate HIV prevention and improve care outcomes on a scale not attempted before. But the success of these combined in a population health strategy depends of their feasibility and acceptability as both individual intervention components and as a package. Comparing research data collected prior to, and after, the start of the TasP trial provides evidence of consistent community acceptance of repeat home-based HIV-testing. Misconceptions around motivations to test, especially around perceptions and definitions of risk behaviours, seem to be evolving very slowly; while community stigma and concerns with confidentiality and social support remained high over time.

Although community members interviewed before the TasP trial supported the idea of repeat and regular HIV-testing, they were not able to appreciate or articulate reasons why people might want to test regularly or repeatedly, apart from that they had been involved in sexual risk-taking. Community members interviewed during the TasP trial, having been exposed to repeated offer of HIV-testing, and to community engagement activities informing people of the benefits of repeat HIV-testing, remained supportive of repeat HIV-testing. Preliminary analysis indeed showed that around 85% of TasP trial participants who tested HIV-negative at first contact accepted to be re-tested at second contact (Larmarange et al., Citation2014). Further, motivation to repeat test remained largely associated with the perception of an HIV risk, specifically related to sexual risk-taking. The 2015 South African HIV guidelines recommend

6–12 monthly repeat testing in the general population depending on risk; 6–12-monthly repeat testing for adolescents if sexually active, or more frequently if they have new sexual partner/s or if not using barrier protection; and repeat testing after 6–12 weeks (window period) among HIV-negative people exposed to HIV risk. (National Department of Health, Citation2015)

We would argue that, in areas of high HIV prevalence and incidence such as Hlabisa sub-district, prevention and testing promotion programmes should aim to convey the messages that everyone who is sexually active is at risk of HIV, and that all will eventually benefit from regular and repeated HIV-testing.

Community members consistently reported perceptions of stigma and prejudice regarding repeat HIV-testing and HIV-testing in general. During the TasP research, these rather focused on modes of testing delivery rather than on the principle of HIV-testing itself. Participants shared increased concern that clinic-based HIV-testing could lead to HIV-positive persons being “seen”, and identified to community members. The distrust in and discomfort with HIV-specific facilities and services needs to be taken into account by public health decision-makers, when thinking about operationalising UTT – and for both the test and the treat components. As previously reported in other contexts (van Rooyen et al., Citation2013), and specifically among females and older people (Maheswaran, Thulare, Stanistreet, Tanser, & Newell, Citation2012), home-based HIV-testing was perceived to be highly acceptable in this context. People appreciated health services provided at home, without people “from the outside” to see them: private/household disclosure was somewhat less feared than social/community disclosure; or maybe HIV test results could be more easily disguised at home than at the clinic, especially if provided with other test results. People also seemed to liked the idea of one-on-one engagement where they could spend time asking questions and discussing issues around testing: they overall identified home-based HIV-testing as potential form of social support. However, opinions were sometimes contrasted, underlining the importance of combination HIV-testing, with multiple HIV-testing options made available in the community, to ensure services are adapted to people’s needs and life situations, and that people can test where they feel most comfortable (World Health Organisation, Citation2015a).

Between the pre-TasP and TasP research periods (2010 and 2013), HIV-testing opportunities multiplied with repeated rounds of home-based HIV-testing being available through the trial, and early treatment was made available in the intervention communities. UTT has thus become a reality for some community members. Many community members interviewed during the TasP trial were aware of the TasP trial procedures, regarding both home and clinic visits. They reported accurately the benefits of repeat testing – early identification of HIV infection and access to early ART. But exposure to UTT does not seem to have overcome the fear of negative social consequences related to HIV and HIV-testing. Throughout, community members seemed to share a socially regulated discourse and perception of what constitutes appropriate sexual behaviour, with HIV remaining associated with “bad sexuality”, and seen as something negative brought on oneself, which may jeopardise social relationships. Community prejudice remained high and social normalisation of HIV through the regular and repeat offer of HIV-testing does not seem to have become a reality yet in Hlabisa sub-district.

One limitation of our research was that at both time-points, we mostly reached and met with female participants; most men were not available during the day and were unable to commit to participating. However, the specific viewpoints of men on UTT is discussed elsewhere in this special AIDS Care issue (Chikovore, Citationin press). Further, the HIV status and HIV-testing experiences of participants, which could have influenced reported perceptions (Young et al., Citation2010), were unknown to the facilitators and the researchers. Our purposive sampling strategy means that our study sample is not representative of the Hlabisa community as a whole. Snowball recruitment of participants in the same community/cluster meant that many knew each other, but the researchers were unaware of the degree of acquaintance between participants. Also, through the course of the study, several participants withdrew from the repeated group discussions, particularly in the younger adults group when they took up job offers away from the community or went back to school. Finally, the Hlabisa sub-district population has benefited from the support of the Africa Centre over many years, in terms of HIV-testing offer and ART roll-out, and may not be representative of all rural communities in KwaZulu-Natal.

Nevertheless, important take-home messages can be drawn from this research. The home-based HIV-testing intervention aimed at reaching universal HIV-testing within the TasP trial area was well received before and during the intervention implementation. However, fear of the negative consequences of HIV-testing remained high over time in these rural Zulu communities. These results suggest that facilitating support for and engagement in regular and repeat HIV-testing could be a challenge for UTT, as it has been for many biomedical HIV prevention strategies (Iwuji, Citation2015). Research on the feasibility, social consequences and costs of innovative approaches should be explored in these communities, including implementing diverse and thus more personalised approaches to HIV-testing and repeat HIV-testing (Makusha et al., Citation2015), as well as providing further opportunities for ART initiation and care at home – as already exists in several cities and peri-urban communities of South Africa.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Department of Health of KwaZulu-Natal and of South Africa for their support of this study, the community of Hlabisa sub-district for hosting our research and all participants who contributed to the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bor, J., Herbst, A. J., Newell, M. L., & Barnighausen, T. (2013). Increases in adult life expectancy in rural South Africa: Valuing the scale-up of HIV treatment. Science, 339(6122), 961–965. doi:10.1126/science.1230413

- Cawley, C., Wringe, A., Isingo, R., Mtenga, B., Clark, B., Marston, M., … Zaba, B. (2013). Low rates of repeat HIV testing despite increased availability of antiretroviral therapy in rural Tanzania: findings from 2003–2010. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e62212. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062212

- Chikovore, J., Gillespie, N., Mc Grath, N., Orne Gliemann, J., & Zuma, T. (in press). Men, masculinity and engagement with Treatment as Prevention (TasP) in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care xxxxxx.

- Corneli, A. L., McKenna, K., Headley, J., Ahmed, K., Odhiambo, J., Skhosana, J., … Agot, K. (2014). A descriptive analysis of perceptions of HIV risk and worry about acquiring HIV among FEM-prEP participants who seroconverted in bondo, Kenya, and Pretoria, South Africa. Journal of International AIDS Society, 17(3 Suppl 2), 19152. doi:10.7448/ias.17.3.19152

- Delavande, A., & Kohler, H.-P. (2012). The impact of HIV testing on subjective expectations and risky behavior in Malawi. Demography, 49(3), 1011–1036. doi:10.1007/s13524-012-0119-7

- Denison, J. A., McCauley, A. P., Dunnett-Dagg, W. A., Lungu, N., & Sweat, M. D. (2008). The HIV testing experiences of adolescents in ndola, Zambia: Do families and friends matter? AIDS Care, 20(1), 101–105. doi: 10.1080/09540120701427498

- Geer, J. G. (1991). Do open-ended questions measure “salient” issues? Public Opinion Quarterly, 55(3), 360–370. doi: 10.1086/269268

- Granich, R. M., Gilks, C. F., Dye, C., De Cock, K. M., & Williams, B. G. (2009). Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: A mathematical model. Lancet, 373(9657), 48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9

- Helleringer, S., Mkandawire, J., Reniers, G., Kalilani-Phiri, L., & Kohler, H. P. (2013). Should home-based HIV testing and counseling services be offered periodically in programs of ARV treatment as prevention? A case study in likoma (Malawi). AIDS and Behavior, 17(6), 2100–2108. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0365-0

- Iwuji, C. (2015). The Art of HIV elimination: Past and present science. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 6(11), 525. doi:10.4172/2155-6113.1000525

- Iwuji, C. C., Orne-Gliemann, J., Tanser, F., Boyer, S., Lessells, R. J., Lert, F., … Dabis, F. (2013). Evaluation of the impact of immediate versus WHO recommendations-guided antiretroviral therapy initiation on HIV incidence: the ANRS 12249 TasP (treatment as prevention) trial in hlabisa sub-district, kwaZulu-natal, South Africa: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials, 14, 230. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-14-230

- Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research. introducing focus groups. BMJ, 311(7000), 299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299

- Larmarange, J., Balestre, E., Orne-Gliemann, J., Iwuji, C., Okesola, N., Newell, M.-L. … Lert, F. (2014). Hiv ascertainment through repeat home-based testing in the context of a treatment as prevention trial (ANRS 12249 TasP) in rural South Africa. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 30(Suppl 1), A287. doi:10.1089/aid.2014.5650

- Maheswaran, H., Thulare, H., Stanistreet, D., Tanser, F., & Newell, M. L. (2012). Starting a home and mobile HIV testing service in a rural area of South Africa. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 59(3), e43–46. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182414ed7

- Makusha, T., Knight, L., Taegtmeyer, M., Tulloch, O., Davids, A., Lim, J., … van Rooyen, H. (2015). Hiv self-testing could “revolutionize testing in South Africa, but it has got to be done properly”: Perceptions of key stakeholders. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0122783. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122783

- Matovu, J. K., Gray, R. H., Kiwanuka, N., Kigozi, G., Wabwire-Mangen, F., Nalugoda, F., … Wawer, M. J. (2007). Repeat voluntary HIV counseling and testing (VCT), sexual risk behavior and HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS and Behavior, 11(1), 71–78. doi:10.1007/s10461-006-9170-y

- National Department of Health. (2015). National consolidated guidelines for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults. Retrieved from http://www.sahivsoc.org/upload/documents/ART Guidelines 15052015.pdf

- Obare, F., Fleming, P., Anglewicz, P., Thornton, R., Martinson, F., Kapatuka, A., … Kohler, H. P. (2009). Acceptance of repeat population-based voluntary counselling and testing for HIV in rural Malawi. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 85(2), 139–144. doi:10.1136/sti.2008.030320

- Orne-Gliemann, J., Larmarange, J., Boyer, S., Iwuji, C., McGrath, N., Barnighausen, T., … Imrie, J. (2015). Addressing social issues in a universal HIV test and treat intervention trial (ANRS 12249 TasP) in South Africa: Methods for appraisal. BMC Public Health, 15, 209. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1344-y

- Prata, N., Morris, L., Mazive, E., Vahidnia, F., & Stehr, M. (2006). Relationship between HIV risk perception and condom use: Evidence from a population-based survey in Mozambique. International Family Planning Perspectives, 32(4), 192–200. doi:10.1363/ifpp.32.192.06

- Regan, S., Losina, E., Chetty, S., Giddy, J., Walensky, R. P., Ross, D., … Bassett, I. V. (2013). Factors associated with self-reported repeat HIV testing after a negative result in Durban, South Africa. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e62362. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062362

- van Rooyen, H., Barnabas, R. V., Baeten, J. M., Phakathi, Z., Joseph, P., Krows, M., … Celum, C. (2013). High HIV testing uptake and linkage to care in a novel program of home-based HIV counseling and testing with facilitated referral in kwaZulu-natal, South Africa. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 64(1), e1–8. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829b567d

- Ryder, K., Haubrich, D. J., Calla, D., Myers, T., Burchell, A. N., & Calzavara, L. (2005). Psychosocial impact of repeat HIV-negative testing: A follow-up study. AIDS and Behavior, 9(4), 459–464. doi:10.1007/s10461-005-9032-z

- Shelton, J. D. (2008). Counselling and testing for HIV prevention. Lancet, 372(9635), 273–275. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61091-0

- Suthar, A. B., Ford, N., Bachanas, P. J., Wong, V. J., Rajan, J. S., Saltzman, A. K. … Baggaley, R. C. (2013). Towards universal voluntary HIV testing and counselling: A systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approaches. PLoS Medicine, 10(8), e1001496–00. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001496

- Tanser, F., Barnighausen, T., Grapsa, E., Zaidi, J., & Newell, M. L. (2013). High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural kwaZulu-natal, South Africa. Science, 339(6122), 966–971. doi:10.1126/science.1228160

- World Health Organisation. (2014). Global update of the health sector response to HIV. Retrieved from Geneva: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128494/1/9789241507585_eng.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organisation. (2015a). Consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services. 5cs: consent, confidentiality, counselling, correct results and connection. Retrieved from Geneva: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/179870/1/9789241508926_eng.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organisation. (2015b). Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/186275/1/9789241509565_eng.pdf

- Young, S. D., Hlavka, Z., Modiba, P., Gray, G., Van Rooyen, H., Richter, L., … Coates, T. (2010). HIV-related stigma, social norms, and HIV testing in Soweto and Vulindlela, South Africa: national institutes of mental health project accept (HPTN 043). JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 55(5), 620–624. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fc6429

- Zaidi, J., Grapsa, E., Tanser, F., Newell, M. L., & Barnighausen, T. (2013). Dramatic increase in HIV prevalence after scale-up of antiretroviral treatment. AIDS, 27(14), 2301–2305. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328362e832

Appendix. Composition of the ANRS 12249 TasP Study Group (as of March 2016)

Scientific advisory board

– Chair: Bernard Hirschel (Switzerland).

– International experts: Xavier Anglaret (Ivory Coast), Hoosen Cooavdia (South Africa), Alpha Diallo (France), Bruno Giraudeau (France), Jean-Michel Molina (France), Lynn Morris (South Africa), François Venter (South Africa), Sibongile Zungu (South Africa).

– Community representatives: Eric Fleutelot (France), Eric Goemaere (South Africa), Calice Talom (Cameroon).

– Sponsor representatives (ANRS): Brigitte Bazin, Claire Rekacewicz.

– Pharmaceutical company representatives: Golriz Pahlavan-Grumel (MSD), Alice Jacob (Gilead).

Data safety and monitoring board

– Chair: Patrick Yeni (France).

– Members: Sinead Delany-Moretlwe (South Africa), Nathan Ford (South Africa), Catherine Hankins (Netherlands), Helen Weiss (UK)