ABSTRACT

Malawi is a global leader in the design and implementation of progressive HIV policies. However, there continues to be substantial attrition of people living with HIV across the “cascade” of HIV services from diagnosis to treatment, and program outcomes could improve further. Ability to successfully implement national HIV policy, especially in rural areas, may have an impact on consistency of service uptake. We reviewed Malawian policies and guidelines published between 2003 and 2013 relating to accessibility of adult HIV testing, prevention of mother-to-child transmission and HIV care and treatment services using a policy extraction tool, with gaps completed through key informant interviews. A health facility survey was conducted in six facilities serving the population of a demographic surveillance site in rural northern Malawi to investigate service-level policy implementation. Survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Policy implementation was assessed by comparing policy content and facility practice using pre-defined indicators covering service access: quality of care, service coordination and patient tracking, patient support, and medical management. ART was rolled out in Malawi in 2004 and became available in the study area in 2005. In most areas, practices in the surveyed health facilities complied with or exceeded national policy, including those designed to promote rapid initiation onto treatment, such as free services and task-shifting for treatment initiation. However, policy and/or practice were/was lacking in certain areas, in particular those strategies to promote retention in HIV care (e.g., adherence monitoring and home-based care). In some instances, though, facilities implemented alternative progressive practices aimed at improving quality of care and encouraging adherence. While Malawi has formulated a range of progressive policies aiming to promote rapid initiation onto ART, increased investment in policy implementation strategies and quality service delivery, in particular to promote long-term retention on treatment may improve outcomes further.

KEYWORDS:

Background

The scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for people living with HIV (PLHIV) in Sub-Saharan Africa over the past 10 years has been remarkable (Bor, Herbst, Newell, & Barnighausen, Citation2013), and Malawi in particular has substantially reduced HIV-attributable adult mortality(Chihana et al., Citation2012; Jahn et al., Citation2008). In the rural north of Malawi, where resource constraints are particularly apparent, the all-cause mortality rate among 15–59-year-olds fell by 32% once ART was introduced, compared to the pre-ART period (Floyd et al., Citation2010). This dramatic decline is the result of a successful public sector HIV treatment program. Malawi was one of the first sub-Saharan countries to adopt a “public health approach” to HIV scale-up, as promoted by the World Health Organization to encourage rapid ART initiation for PLHIV (Gilks et al., Citation2006). Despite recent improvements in ART retention, substantial attrition across the HIV diagnosis-to-treatment “cascade” of services continues to result in excess deaths among PLHIV before, and after initiating ART (Jahn et al., Citation2008; Koole et al., Citation2014; McGrath et al., Citation2010; Parrott et al., Citation2011; Wringe et al., Citation2012; Zachariah et al., Citation2006).

The network for Analyzing Longitudinal Population-based data on HIV in Africa (ALPHA) is investigating mortality among PLHIV during the ART era, using longitudinal data from 10 health and demographic surveillance sites (HDSS) in six high prevalence countries: Kenya, Malawi (Karonga), South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe. As part of this research program, a study was conducted to understand policy and programmatic factors that facilitate or inhibit PLHIV from accessing and staying on treatment; aiming to investigate whether policy implementation differences could explain variations in the distributions of deaths among PLHIV across the diagnosis-to-treatment cascade.

Earlier work has shown that Malawi has more policies to promote rapid progression of PHLIV through the cascade than other countries (Church et al., Citation2015). In this paper, we explore national HIV policy and its implementation within the Karonga HDSS in northern Malawi by contrasting policy review findings with health facility survey data to provide rich contextual analysis of HIV policy implementation in this setting.

Methods

Study setting

By 2012, there were approximately 950,000 adults aged >15 living with HIV in Malawi (UNAIDS, Citation2012), corresponding to an adult prevalence of 10.8% (National Statistics Office (NSO), Citation2011). There were 724 static and 188 outreach testing sites, and 707 static ART sites in mid-2014 (Ministry of Health Malawi, Citation2014a). By September 2014, an estimated 521,319 adult patients were alive and on ART, and 78% of adults initiating ART were retained in care one year later (Ministry of Health Malawi, Citation2014a).

The HDSS was established in 2002 in Karonga District, and has conducted HIV serosurveys since 2005. The site is located in a rural area of 135 km2, with a population of approximately 37,500. HIV prevalence in the HDSS was estimated at 7% of men and 9% of women in 2012 (Floyd et al., Citation2012). Free ART became available in Karonga district in 2005, and within the HDSS in 2006.

Policy review

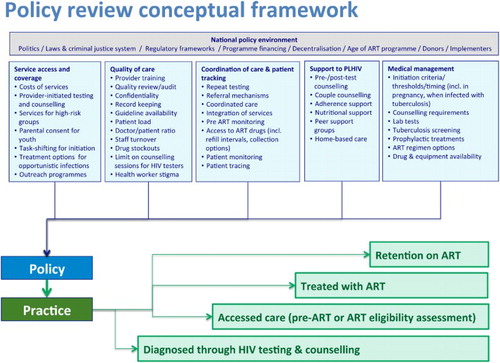

We applied a policy framework developed by Church et al. (Citation2015; ), devised by reviewing WHO policies/guidelines and the literature, with expert review by a group of HIV researchers and clinicians. The framework includes 54 indicators describing service coverage and access, quality of care, coordination of care and patient tracking, support to PLHIV and medical management.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of policy and service factors influencing adult mortality across the diagnosis-to-treatment cascade. Reproduced from Church et al. (Citation2015).

We reviewed all national Malawian policies and guidelines published between January 2003 and June 2013 on adult HIV testing and counseling (HTC), prevention of mother-to-child transmission services (PMTCT), and HIV care and treatment. Eighteen documents were reviewed (policy statements, clinical guidelines, training manuals and strategies), and policy information was systematically extracted into an Excel tool, noting policy content, source, year of policy, and changes between 2003 and 2013. Policy data were then synthesized into a series of indicators categorized according to whether they were: (i) explicit; (ii) implicit or with caveats or exceptions; (iii) unclear or conflicted with other policies; or (iv) no policy in this area. Further details on this process are provided elsewhere (Church et al., Citation2015).

KI interviews

Three semi-structured interviews with key informants (KI) from the National AIDS Commission, the Ministry of Health HIV/AIDS unit, and a researcher/clinician working on HIV/AIDS at an NGO were conducted to fill in gaps in the document review. KI also provided their views on policy implementation, and these insights helped to shed light on the reality of service delivery. Interviews were audio-recorded, and notes were taken.

Facility survey

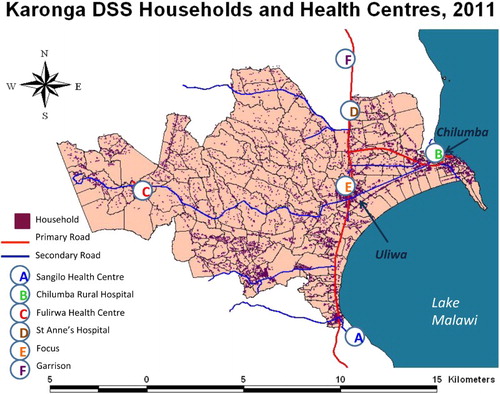

A structured questionnaire was designed to investigate implementation of policy in adult HTC, PMTCT, and HIV care and treatment. The survey was conducted in December 2013 in all six facilities with catchment areas within the Karonga HDSS that provided HIV treatment services (n = 5), or community support and HTC services (n = 1) (). Of the five facilities providing HIV treatment, one was a rural hospital, and four were rural health centers. A nurse interviewer conducted the group interviews in English with the Officer-in-charge and other healthcare providers involved with HIV services at each health facility. Participants gave informed consent, and interviews took around 90 minutes.

Figure 2. Karonga HDSS and location of health facilities. Copyright Malawi Epidemiology and Intervention Research Unit. Permission to reproduce has been given.

Ethical approval for the facility survey was granted by the Malawi National Health Sciences Research Committee. The facility survey data were analyzed descriptively using Stata 12 according to the same 54 indicators that were assessed for the policy review.

Results

The national policy response to the HIV epidemic in Malawi

There have been two points of major change in HIV care and treatment in Malawi. The public sector rollout of the ART program in 2004 was groundbreaking, bringing the potential for wide-scale delivery, and the landscape of HIV treatment changed completely. Prior to this, there was ad hoc small-scale private treatment confined to major cities and mostly delivered by non-governmental organizations to a few patients (NAC Ministry of Health Malawi, Citation2005). The “public health approach” meant patients initiating ART did not require CD4 counts, virology or other laboratory tests, with eligibility assessment based on clinical screening only; those assessed as being in WHO Clinical Stage 3 or 4 were eligible to receive ART.

A second major change in the provision of HIV services occurred in 2011 when the 1st edition of the “Malawi Guidelines for Clinical Management of HIV in Children and Adults” was compiled (Ministry of Health Malawi, Citation2011). This focused on improving access to PMTCT and ART, including the introduction of the “Option B+” policy in 2011, which recommended that all HIV-positive pregnant or breastfeeding women initiate lifelong ART following diagnosis. Malawi was the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to adopt this policy, even before WHO recommended it in 2012 (World Health Organization, Citation2012).

The 2011 guidelines also brought in CD4 testing, and indicated for the first time that ART should be initiated for patients with WHO clinical stages 1 and 2, if they also had a CD4 count below 350 cells/mm3. Stavudine was phased out and policy recommended tenofovir/lamivudine/efavirenz for new patients, starting with TB patients and pregnant women, and those with lipodystrophy (Ministry of Health Malawi, Citation2011).

HIV policy implementation

There were 2–6 participants per interview group in the facility survey. Respondents included: clinical officers, nurse midwives, medical assistants and HTC counselors. – present information on the indicators, and describe how policies are being implemented in the six facilities, with regard to HTC, HIV care and treatment, and retention in care.

Table 1. Access to HIV testing and counseling.

Table 2. Access to HIV care and treatment.

Table 3. Factors influencing retention in care.

Practice complies with policy guidelines, fully or partially

For some indicators, practice complied with national policies. For example, in all surveyed facilities, free HTC (), PMTCT and ART () services were reported. Individual, group and couple pre-test counseling is conducted in most facilities, which aligns with policy (). Provision of free HIV services was not restricted to government facilities: service-level agreements with faith-based facilities extended coverage of free HIV care, in line with policy ( and ).

PMTCT is available at all five antenatal care (ANC) facilities (). Quality of care reviews are routinely conducted ( and ), although it was not clear whether these were as comprehensive as policy indicated (). No laboratory tests were required for PLHIV to initiate ART, in line with policy.

Policies to promote rapid initiation were implemented including task sharing to nurses and medical assistants, and rollout of ART initiation to all facilities (), thus making treatment rapidly accessible for many more people. All facilities offered isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) in the pre-ART phase, and all had Isoniazid in stock at the time of survey (). All facilities provided some form of counseling following signs of poor adherence () (pill counts and active dialogue are supposed to be employed to identify signs of poor adherence).

In some instances, policy was only partially implemented. For example, while provider-initiated testing and counseling (PITC) was national policy, and all facilities with ANC offered it to pregnant women, only four facilities routinely offered HTC to other groups (e.g., out-patients, TB and family planning clients), and four facilities only offered “opt-in” testing (). ART initiation through Option B+ policy was implemented in 4/5 facilities offering ART (), and ART patients were given two-monthly drug supplies once stable, not three as indicated by the policy (). Variations across facilities were observed in procedures following missed visits, treatment defaults and TB screening, and the number of first-line regimens offered also varied ().

Policy not implemented, or unclear

Indicators of practice not adhering to policy included: infringement of anonymous HIV testing by recording names in registers (); referral of HIV-positive pregnant women from ANC to the ART clinic during pregnancy in spite of clear guidance since 2012 that women should initiate and be maintained on treatment within ANC until after delivery (); low provision of refresher training for HIV care providers (); limited diligence in investigating adherence (). While all facilities did report pill counts to monitor adherence, the failure to ask patients specifically about pill-taking suggests that the move towards an “active dialogue” as outlined in the policy was absent.

Practice exceeds policy guidelines

Although Malawi had policy gaps in relation to ART registration, adherence and quality of care, the facility surveys demonstrated that there were often alternative practices being implemented, which focused on adherence and quality of care. For example, although there was no clear policy guidance on referral procedures to link diagnosed clients with ART sites, facilities reported a range of strategies to track patients’ post-diagnosis and ensure registration in HIV care services. Five facilities reported documentation of referral in patient notes, three provided referral letters to patients, two completed registers/logbooks, and one used a referral form. Furthermore, three facilities reported checking HIV care registers to ensure that registration occurred. A healthcare worker accompanied clients to the ART unit in two of the facilities to ensure registration ().

Similarly, while there were policy gaps regarding home-based care and peer support, other policies and practices may have compensated for this. For example, Malawi policy indicates that patients must have follow-up counseling following signs of poor adherence, and be given clear practical advice (). Policy documents also stated that patients should be asked to consent to active follow-up at the time of initiating ART. Facilities themselves also took the initiative in this area; three reported support groups for PLHIV in the community, and all five reported home-based care was provided either by them, another facility, or at the community level, although these programs were small scale and dependent on local circumstances.

While there was no specific national policy on targeted testing of high-risk groups, most facilities offered testing to some groups, notably sex workers. A key informant also noted that mobile clinics targeted sex workers and truck drivers in hot spots. Clinics had also preceded national policy in the delivery of first-line ART regimens. At the time of the survey, national policy stipulated D4 T/3TC/NVP (Stavudne/Lamivudine/Nevirapine) provision, yet all five facilities with ART were already delivering a tenofovir-based regimen (made available due to the Option B+ policy for pregnant or breastfeeding women), which subsequently became policy for all adults.

Discussion

Our policy review demonstrates that the Malawian government has taken a groundbreaking public health approach to developing national HIV policies in order to encourage as many PLHIV as possible to access and adhere to treatment. Furthermore, these policies covering testing, PMTCT and retention in HIV care have generally been successfully implemented in facilities in this poor, rural and remote setting. However, despite a general picture of successful implementation, we documented several areas of disconnect between policy and practice that are likely to contribute to attrition along the diagnosis-to-treatment cascade, and attention to these could improve retention in care.

For example, the observation that healthcare providers continued to rely on the pill count rather than engage in active dialogue with the patient is concerning, although likely explained by the additional workload and lack of complex provider skills. Furthermore, as the MoH had identified that immediate referral from ANC to ART for pregnant women was not effective, the fact that several facilities continued to make this referral as soon as pregnant women were found to be positive could explain why some drop out of care. A separate analysis found that shortly after Option B+ implementation, almost half of HIV-positive pregnant women in the HDSS and not already on ART when they became pregnant had not initiated lifelong ART by the time of delivery (Price, Citation2014). Similarly, there was lower retention in care among women initiated on ART because of Option B+, compared to women of childbearing age initiated on ART because of clinical or CD4 cell count criteria (Koole et al., Citation2014).

In some instances, failure to comply with national policy may have contributed to improved rates of linkage to care. For example, while an anonymous HIV testing policy may have been designed to reduce stigma and fear of disclosure, recording names in HIV testing registers may promote patient tracking, identification and entry into care. An unexpected finding in this study was the discovery that several health facilities were implementing activities that went beyond national policies. For example, we documented good referral services from HTC and ANC services to the ART clinic in the facility survey, despite a lack of policies on linking positive individuals from testing services to HIV care and treatment. It has been shown that progression from HTC to ART is comparatively fast (Reniers et al., Citation2015), and this is likely due to these enhanced procedures, although it may also reflect the exposure of this population to the HIV serological surveys which include opportunities for HIV testing and referrals.

Our analysis has indicated that many of Malawi’s progressive policies are implemented, for example, most women initiate ART in line with the Option B+ policy, although their impacts on retention and mortality remain uncertain. For example, Option B+ resulted in a 49% increase in ART coverage among HIV-infected pregnant women in 18 months (Tippett Barr, Citation2013), but treatment default rates among pregnant or breastfeeding women are higher than among non-pregnant women, with Option B+ patients five times more likely to never return after their initial clinic visit than women starting ART with advanced disease progression (Tenthani et al., Citation2014). These findings suggest that further research is needed to investigate the impact of Option B+ policy implementation on adherence, drug resistance rates, and mortality.

Since the policy review was conducted, a second edition of the Malawi Guidelines for the Clinical Management of HIV in Children and Adults was published in April 2014. These took a new direction with emphasis on better monitoring using viral load testing, to improve identification of treatment failure and ensure timely initiation of second-line treatments and further improved quality of care. These guidelines also indicated that ART should be initiated in adults with CD4 counts <500 (Ministry of Health Malawi, Citation2014b) even in the absence of AIDS-defining illnesses, moving closer to a test-and-treat approach.

The approach taken in this work, drawing on qualitative policy data, quantitative facility survey data, and interviews with key informants, has helped to inform review of HIV policy and its implementation. This model may be useful in other settings. Similar analyses are being conducted in other ALPHA sites as well as a review across countries (Church et al., Citation2015). Findings have been shared with the Malawi Ministry of Health HIV Unit (through author SM) and Karonga District Health Office (through author CS).

There are certain limitations to this analysis that must be considered. Firstly, the facility surveys only covered six facilities in a small area in northeast Malawi, and therefore our findings are not representative of the whole country. Certain findings from the facility survey were, however, supported by our KI interviews, suggesting that the findings from the facility survey are not unique to the study area. In this respect, KIs bridged the information between policy (from the review) and practice (from facilities) as they had insights to share on both.

Secondly, healthcare providers may have thought that they were being audited and presented their work and facility in an optimal light. Despite an explicit introduction by the interviewers, respondents may have thought that they should answer what is supposed to happen according to their own training, rather than what happens in reality. We tried to limit this by providing detailed information on the purpose of the study, and stressing the anonymity of the results before carrying out the interviews.

Finally, no data were collected from patient interviews. Patients’ experiences of implementation are likely to vary and differ from provider reports. Our KIs suggested, for example, that patients may be charged prescription fees, which was not reported in our surveys. Qualitative interviews with PLHIV across the cascade are being conducted to better understand their perspectives on HIV service delivery and how different policies influence care-seeking behavior. Future analyses should also quantify which policies and practices are most effective in improving retention in care and reducing mortality, by incorporating mortality data among HIV-infected persons in this setting.

This analysis demonstrates where national policies are being implemented in health facilities in northern Malawi; and identifies policy implementation gaps as well as where practices exceed national recommendations. Addressing areas of shortfall, while reinforcing areas of excellence, could improve retention across the diagnosis-to-treatment cascade and reduce mortality among PLHIV.

Addendum

Since the submission of this article, a viral load monitoring plan has been launched in Malawi, together with a commitment to move towards the WHO recommendation for immediate treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the three key informants for their time to be interviewed and assistance with this work: Andreas Jahn (Ministry of Health HIV/AIDS unit), Andrina Mwansambo (National AIDS Commission) and Joep van Oosterhout (Dignitas). We thank Basia Zaba for helpful comments on the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

† Affiliation where research conducted: The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

References

- ART (2011). Clinical Management of HIV in Children and Adults: Malawi Integrated Guidelines for Providing HIV Services in ANC, Maternity, Under 5, FP, Exposed Infant/Pre-ART, ART Clinics. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health.

- Bor, J., Herbst, A. J., Newell, M. L., & Barnighausen, T. (2013). Increases in adult life expectancy in rural South Africa: Valuing the scale-up of HIV treatment. Science, 339(6122), 961–965. doi: 10.1126/science.1230413

- Chihana, M., Floyd, S., Molesworth, A., Crampin, A. C., Kayuni, N., Price, A., … French, N. (2012). Adult mortality and probable cause of death in rural northern Malawi in the era of HIV treatment. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 17, e74–e83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02929.x

- Church, K., Kiweewa, F., Dasgupta, A., Mwangome, M., Mpandaguta, E., Gomez-Olive, F. X., … Zaba, B. (2015). A comparative analysis of national HIV policies in six African countries with generalised epidemics. WHO Bulletin, 93, 457–467.

- Floyd, S., Marston, M., Baisley, K., Wringe, A., Herbst, K., Chihana, M., … Zaba, B. (2012). The effect of antiretroviral therapy provision on all-cause, AIDS and non-AIDS mortality at the population level – A comparative analysis of data from four settings in Southern and East Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 17(8), e84–e93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03032.x

- Floyd, S., Molesworth, A., Dube, A., Banda, E., Jahn, A., Mwafulirwa, C., … French, N. (2010). Population-level reduction in adult mortality after extension of free anti-retroviral therapy provision into rural areas in northern Malawi. PLoS ONE, 5, e13499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013499

- Gilks, C. F., Crowley, S., Ekpini, R., Gove, S., Perriens, J., Souteyrand, Y., … De Cock, K. (2006). The WHO public-health approach to antiretroviral treatment against HIV in resource-limited settings. The Lancet, 368, 505–510. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69158-7

- Jahn, A., Floyd, S., Crampin, A. C., Mwaungulu, F., Mvula, H., Munthali, F., … Glynn, J. R. (2008). Population-level effect of HIV on adult mortality and early evidence of reversal after introduction of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. The Lancet, 371(9624), 1603–1611. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60693-5

- Koole, O., Houben, R., Mzembe, T., Van Boeckel, T., Kayange, M., Jahn, F., … Crampin, A. (2014). Improved retention of patients starting antiretroviral treatment in Karonga District, northern Malawi, 2005–2012. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 67(1), e27–e33. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000252

- McGrath, N., Glynn, J., Saul, J., Kranzer, K., Jahn, A., Mwaungulu, F., … Crampin, A. (2010). What happens to ART-eligible patients who do not start ART? Dropout between screening and ART initiation: A cohort study in Karonga, Malawi. BMC Public Health, 10(601), 22–44.

- Ministry of Health Malawi. (2003). Guidelines for the use of ART in Malawi, 1st edition, Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Health Malawi. (2006a). A 5-year plan for the provision of ART and good management of HIV-related diseases to HIV-infected patients in Malawi 2006–2010. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Health Malawi. (2006b). The 5-year plan to scale up HCT services in Malawi, 2006–2010, Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Health Malawi. (2006c). Guidelines for the use of ART in Malawi, 2nd edition. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Health Malawi. (2008). Guidelines for the use of ART in Malawi, 3rd edition. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Health Malawi. (2009). Guidelines for HIV counseling and testing, 3rd edn. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Health Malawi. (2010). Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV and paediatric HIV care guidelines. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Health Malawi. (2011). Clinical Management of HIV in Children and Adults: Malawi Integrated Guidelines for Providing HIV Services in ANC, Maternity, Under 5, FP, Exposed Infant/Pre-ART, ART Clinics (M. o. Health, Trans.). Lilongwe: Author.

- Ministry of Health Malawi. (2014a). Integrated HIV program report: July–September 2014.

- Ministry of Health Malawi. (2014b). Malawi Guidelines for Clinical Management of HIV in Children and Adults. (2nd ed.). Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health.

- NAC Ministry of Health Malawi. (2005). Policy on Equity in Access to ART in Malawi. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health.

- National Statistics Office (NSO). (2011). Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Zomba: National Statistics Office and ICF Macro.

- Parrott, F., Mwafulira, C., Ngwira, B., Nkhwazi, S., Floyd, S., Houben, R., … French, N. (2011). Combining qualitative and quantitative evidence to determine factors leading to late presentation for antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. PLoS ONE, 6(11), e27917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027917

- Price, A., Kayange, M., Zaba, B., Chimbandira, F., Jahn, A., Chirwa, Z., … Crampin, A. (2014). Uptake of prevention of mother-to-child-transmission using Option B+ in northern rural Malawi: A retrospective cohort study. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 90(4), 309–314.

- Reniers, G., Slaymaker, E., Kasamba, I., Crampin, A. C., Nyirenda, M., Mugurungi, O., … Zaba, B. (2015). Population-level trends in the uptake of services and the survival of HIV positives Presentation at 20th International AIDS Conference, 20–25 July 2014, Melbourne, Australia.

- Tenthani, L., Haas, A. D., Tweya, H., Jahn, A., van Oosterhout, J.J., Chimbwandira, F., … Olivia, K. (2014). Retention in care under universal antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women (‘Option B+’) in Malawi. AIDS, 28(4), 589–598. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000143

- Tippett Barr, B., Mhango, E., Tenthani, L., Zomba, G., Makombe, S., Eliya, M., …Jahn, A. (2013). Uptake and retention in Malawi’s Option B+ PMTCT program: Lifelong ART for all HIV+ pregnant or lactating women. Paper presented at the CROI 2013, Atlanta.

- UNAIDS. (2012). Country profiles: Malawi. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/malawi/

- World Health Organization. (2012). Program update: Use of antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants. Geneva: Author.

- Wringe, A., Floyd, S., Kazooba, P., Mushati, P., Baisley, K., Urassa, M., … Zaba, B. (2012). Antiretroviral therapy uptake and coverage in four HIV community cohort studies in sub-Saharan Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 17(8), e38–e48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02925.x

- Zachariah, R., Fitzgerald, M., Massaquoi, M., Pasulani, O., Arnould, L., & Harries, A. D. (2006). Risk factors for high early mortality in patients on antiretroviral treatment in a rural district of Malawi. AIDS, 20, 2355–2360. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801086b0