ABSTRACT

To address the economic drivers of poor HIV care and treatment outcomes, household economic strengthening (HES) initiatives are increasingly being implemented with biomedical and behavioral approaches. The evidence linking HES with HIV outcomes is growing, and this evidence review aimed to comprehensively synthesize the research linking 15 types of HES interventions with a range of HIV prevention and treatment outcomes. The review was conducted between November 2015 and October 2016 and consisted of an academic database search, citation tracking of relevant articles, examination of secondary references, expert consultation, and a gray literature search.

Given the volume of evidence, the results are presented and discussed in three papers, each focused on a different HIV outcome area. This is the third paper in the series and focuses on the 38 studies on retention in HIV care, ART adherence, morbidity, and HIV-related mortality. Monthly food rations and conditional cash transfers are associated with improvements in care seeking and medication pick-up. Transportation assistance, income generation and microcredit show positive trends for care and treatment, but evidence quality is moderate and based heavily on integrated interventions. Clinical outcomes of CD4 count and viral suppression were not significantly affected in most studies where they were measured.

Introduction

Retention in care and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) are essential to achieving viral suppression, which reduces AIDS-related deaths as well as onward transmission of the virus. In 2014, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) established ambitious treatment targets to increase the proportion of people living with HIV (PLHIV) who are diagnosed, receiving treatment, and virally suppressed. These targets highlight that, while ART coverage has increased dramatically over the last 15 years, challenges persist for long-term retention in care and viral suppression (UNAIDS, Citation2014). In line with these targets, in 2015 the World Health Organization revised its treatment guidance, recommending that ART be provided to all people who test positive regardless of CD4 count or clinical disease stage (known as the “test and treat” approach). As a result, notable progress has been made in recent years, and in 2016, an estimated 53% of PLHIV aged 15–49 globally were receiving ART, and 44% were virally suppressed (UNAIDS, Citation2017). However, significant gaps remain, and as more people start treatment under the test and treat approach, keeping them in care and adherent to ART will be essential to epidemic control.

Poverty and economic insecurity are known barriers to routine access to HIV care and treatment services (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2014). The global HIV burden is concentrated in resource-limited settings (Kharsany & Karim, Citation2016) and, in these contexts, the direct and indirect costs of care-seeking can prevent adherence and retention. Transportation costs, time away from productive economic activities, and the costs of medical services create barriers to care and treatment (Weiser et al., Citation2003), which are particularly challenging for those who are not economically stable. Poverty is also highly correlated with food insecurity, which can affect adherence in multiple ways. When hunger or side-effects from ARTs are heightened by a lack of food, food insecure PLHIV may choose not to take their medications. Trade-offs between finding or paying for food and accessing treatment can also lead to missed appointments, or even selling medications (Young, Wheeler, McCoy, & Weiser, Citation2014). Lack of food also contributes to immunologic decline, which can reduce ART adherence (Kalichman et al., Citation2014).

To address the economic drivers of poor care and treatment outcomes, household economic strengthening (HES) interventions are increasingly being implemented in coordination with biomedical and more traditional behavioral approaches. HES encompasses a range of strategies that seek to enhance household economic resilience. HES services can complement clinical HIV services by addressing financial barriers to care and treatment and mitigating other economic challenges associated with HIV/AIDS. HES interventions that support retention in care and medication adherence may contribute to better health outcomes for PLHIV and further reductions in transmission of HIV (Haberer et al., Citation2017).

This is the final paper in a three-part evidence review that comprehensively documents the published and gray literature on a broad set of HES interventions and their effect on a range of HIV outcomes. This paper focuses on ongoing care and treatment outcomes, including retention in clinical care, ART adherence, morbidity and mortality. The first and second papers in the series (Swann, Citation2018a, Citation2018b) cover prevention outcomes, and HIV testing and linkage to care, respectively ().

Table 1. HIV outcomes assessed.

HES interventions can be classified into three categories: provision, protection, and promotion. Provision interventions support basic needs; protection interventions help smooth consumption and protect assets against shocks; and promotion interventions help households to grow their income and assets (Woller, Citation2011). Results are presented by individual HES intervention, and discussed in the context of these wider categories. Descriptions of each HES intervention are provided in .

Table 2. HES interventions assessed.

Methods

The methodology of this review was described in detail in the first paper in this series (Swann, Citation2018a) including a description of the search strategy, quality assessment approach, study classification and search terms. Briefly, the review was conducted between November 2015 and October 2016. The initial search was completed using nine academic databases. Four consistent search strings were entered into each database using a list of HES interventions, plus terms associated with different HIV outcomes or population groups. Included evidence had to meet the following criteria: (1) evaluated one or more HES intervention of interest, (2) reported on at least one HIV outcome of interest, (3) available in English, and (4) relevant to low-income contexts or vulnerable populations. There were no geographic exclusion criteria, but studies conducted in high-income countries were only included in the review if the intervention and findings were relevant to low-income or otherwise vulnerable groups. Articles from the initial search were screened for inclusion based on a review of the title and abstract by two reviewers. Relevant records then underwent a full text review by the study author.

Using a citation tracking approach, the reference sections of each of the selected papers were screened for additional pertinent research. In addition, all secondary sources identified in the initial search were reviewed, and all source studies meeting the criteria were included. Recommendations for additional citations were solicited from experts in this field through a half-day consultative meeting. Finally, a gray literature search was conducted.

All evidence was assessed for quality using the Department for International Development’s Assessing the Strength of Evidence methodology (DFID, Citation2014). This assessment tool has 20 questions grouped under seven principles of quality: conceptual framing, transparency, appropriateness, cultural sensitivity, validity, reliability, and cogency. Using the quality assessment results, which provided an overall score between 7 and 21, each citation was given a rating of high, medium-high, medium or low based on pre-defined cut-off points. This assessment was only applied to written articles as there was insufficient information to complete the assessment for conference abstracts and presentations.

For quantitative studies, findings were classified as positive or negative if the results were statistically significant according to a p ≤ 0.05 threshold. Where tests of statistical significance were not conducted/presented, results were classified as null even when directional trends were strong. For qualitative studies, results were classified as positive or negative based on the qualitative data and interpretations presented. Many studies looked at the effectiveness of integrated programs, grouping multiple HES, health and/or social services. Whether a study assessed the independent relationship between a specific HES component and the outcome(s) of interest was an important element of analysis.

Results

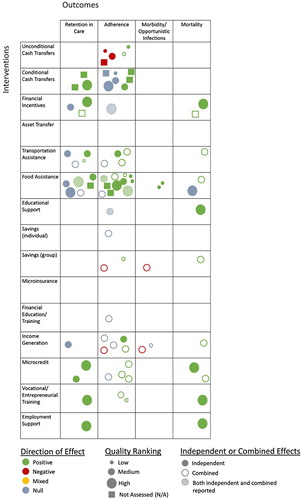

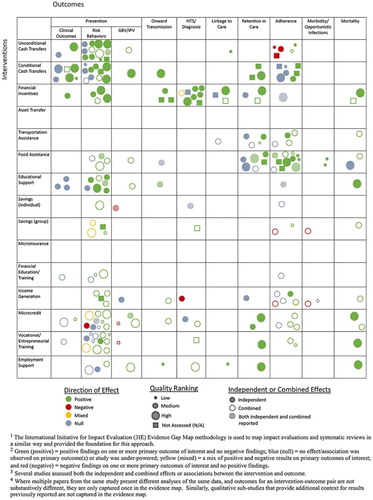

Results for the full review are reported in the first paper in this series (Swann, Citation2018a), including overall study characteristics, PRISMA diagram (see Appendix 1) and full evidence map (see Appendix 2) (Snilstveit, Vojtkova, Bhavsar, Stevenson, & Gaarder, Citation2016).

Evidence for ongoing care and treatment outcomes

From all search methods, 3309 unique records were identified and screened; 436 records underwent a full-text review. A total of 108 citation were included in the full evidence review, 38 of which evaluated ongoing care and treatment outcomes and were included in this paper. Of those 38, the majority (79%) measured an adherence outcome, while 32% measured retention in care; morbidity and mortality outcomes were each measured by nearly 11% of the studies (11 studies reported on more than one outcome area). Retention in care outcomes include self-reported and clinical record data on appointment attendance and accessing HIV-related care over time. Adherence outcomes include self-reported measures, clinical records on medication pick up, pill counts or bottle openings, and clinical data on immune response (CD4 count) and viral load. Morbidity includes self-reported and clinical record data on physical illness or opportunistic infections. Fifty percent of the studies in this paper used at least some self-reported outcomes which can be susceptible to bias; this should be considered when interpreting the findings. The evidence map excerpt for ongoing care and treatment outcomes is provided in .Footnote1

Given the diversity in study characteristics – geography, target group, intervention implementation, study design, sample size, outcome indicators, and overall study contexts – in most cases the studies in this review have only limited comparability. The summary of literature for each intervention instead highlights patterns within these characteristics but does not seek to explicitly compare the studies. Even when the same outcome was measured, variation in these characteristics as well as different analysis methods make it difficult to directly compare effect sizes between studies. The study characteristics and effect sizes are summarized in –, providing important information when interpreting these results. Where studies included multiple HES interventions they are discussed in each relevant section.

Table 3. Studies of unconditional cash transfers on adherence and retention outcomes.

Table 4. Studies of conditional cash transfers on retention and adherence outcomes.

Table 5. Studies of financial incentives on retention and adherence outcomes.

Table 6. Studies of transportation assistance on retention and adherence outcomes.

Table 7. Studies of food assistance on retention and adherence outcomes.

Table 8. Studies of educational support on retention and adherence outcomes.

Table 9. Studies of savings on retention and adherence outcomes.

Table 10. Studies of financial education and training on retention and adherence outcomes.

Table 11. Studies of income generation on retention and adherence outcomes.

Table 12. Studies of microcredit on retention and adherence outcomes.

Table 13. Studies of vocational and entrepreneurial training on retention and adherence outcomes.

Table 14. Studies of employment support on retention and adherence outcomes.

Provision interventions

Unconditional cash transfers

Five studies assessed the effect of unconditional cash transfers (UCTs) on adult HIV adherence, and findings were mixed (). One study was medium quality, three were low quality, and one was not able to be assessed for quality, highlighting a weak evidence base. Three studies evaluated the effect of the South Africa Disability Grant (SADG) on ART adherence. Eligibility for the SADG required CD4 counts below a defined threshold, and all three studies found that this requirement incentivized poor adherence to maintain grant eligibility (Haber et al., Citation2015; Jones, Citation2011; Phaswana-Mafuya et al., Citation2009). Because eligibility was tied to a low CD4 count, these results should not be generalized to other UCT interventions. The other two studies found positive associations between UCTs and self-reported ART adherence among adults, though one was a small qualitative study in Malawi (Miller & Tsoka, Citation2012), and in the other, transfers were only provided to highly vulnerable households in Ethiopia and were combined with several other forms of support (Bezabih, Citation2016).

Conditional cash transfers

Eight studies examined CCTs and retention and adherence outcomes, including one that evaluated retention in prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services (). Two studies were high quality, while two were medium, and one was low quality; three were not assessed. Five of the studies used experimental designs, more than any other intervention in this paper. At the same time, almost half of the studies were pilot feasibility studies, and five were conducted in high-income countries with diverse or vulnerable target groups. The wide range of transfer amounts (USD 2–100) and frequencies limit the comparability of results. There was also variation in the conditions – including clinical appointment attendance, correctly-timed pill bottle openings, and viral suppression – all of which were directly associated with the study outcomes.

A pilot CCT study with ART patients in the United States (U.S.) found that, among those with a detectable viral load at baseline, the proportion of undetectable viral load tests increased over the intervention period (Farber et al., Citation2013). A small study in the United Kingdom reported only trends of higher CD4 counts and greater viral suppression among perinatally infected adolescents receiving CCTs (Foster et al., Citation2014). Three other studies, all of which used experimental designs, found improvements on measures such as clinical appointment attendance (El-Sadr et al., Citation2015; Solomon et al., Citation2014), and timed pill bottle openings (Rigsby et al., Citation2000), but not on viral load or CD4 count. Similarly, clients participating in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Tanzania receiving nutrition assessment and counseling (NAC) plus a CCT were more likely to be retained in care and adherent compared to those receiving NAC only; clinical outcomes were not measured (McCoy et al., Citation2016).

Qualitative findings from a U.S.-based RCT sub-study found that CCTs were particularly motivating for moderate adherers at baseline (Tolley et al., Citation2016). A final experimental study in the Democratic Republic of the Congo found that CCTs given to HIV-positive pregnant women supported retention throughout the PMTCT cascade (Yotebieng et al., Citation2016).

Financial incentives

Four studies examined associations between financial incentives and ongoing care and treatment (). Two studies were high quality, while one was medium, and one was not assessed. A wide range of incentive amounts were used, each of which incentivized unique behaviors, limiting their comparability. The first study found that participants in an integrated community-based program in Uganda who received rent support had lower loss to follow-up (LTFU) and mortality than participants not getting this support (Talisuna-Alamo et al., Citation2012). Similarly, participants in an experimental study of a combined intervention in Swaziland that included incentives for attending clinical appointments had higher retention and lower risk of death (McNairy et al., Citation2016). A U.S.-based RCT with hospitalized substance users also found that financial incentives were initially effective in improving viral suppression but effects were not sustained (Metsch et al., Citation2016). A final study in Cambodia found no association between receipt of occasional cash assistance and retention in care (Daigle et al., Citation2015).

Transportation assistance

Seven studies evaluated transportation assistance (). A range of study designs were employed. Of these, one was medium-high quality, while five were medium, and one was low quality. Three studies assessed programs that included transport assistance as only one component of more comprehensive adherence-focused interventions. Two reported positive results on outcomes of viral suppression, mortality, self-reported adherence (Muñoz et al., Citation2011) and adherence verified through pill counts (Nyamathi et al., Citation2012), while the third reported only trends of higher CD4 counts (Rich et al., Citation2012). A fourth study, found no independent association between transport assistance and ART appointment adherence in Cambodia (Daigle et al., Citation2015).

Qualitative data from studies of combined interventions in Tanzania, India and Cambodia indicate that the provision of transportation assistance, specifically, increased access to clinical sites for ART (Nsigaye et al., Citation2009; Zaveri, Citation2008), and participants in another qualitative study in Zambia reported that free transport to the clinic facilitated adherence (Sanjobo et al., Citation2008).

Food assistance

Fourteen studies evaluated food assistance and HIV care and treatment outcomes (). Of these, three studies were high quality, while two were medium-high, four were medium, and three were low quality; two were not assessed. Most evaluated food assistance in the context of other clinical or community-based programing, including health, psychosocial, and/or economic services, though 11 still assessed food assistance independently.

Eight studies evaluated monthly food rations for adult PLHIV in Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and the U.S., all of which had positive findings for at least some of the care and treatment outcomes studied, with no negative results (Byron et al., Citation2008; Cantrell et al., Citation2008; Egge & Strasser, Citation2006; Ivers et al., Citation2010; Martinez et al., Citation2014; McCoy et al., Citation2016; Tirivayi et al., Citation2012). While positive results were found for self-reported adherence, medication pick-up and appointment attendance, the only study that measured clinical outcomes found no association with improved CD4 counts (Tirivayi et al., Citation2012). A study with South African adolescents also found that food support was associated with better self-reported ART adherence in this population (Cluver et al., Citation2016). In contrast, a study in Cambodia found no association between receipt of food assistance and appointment adherence, though food was provided inconsistently, distinguishing this from predictable rations (Daigle et al., Citation2015).

Three studies evaluated community-based ART interventions that incorporated other support, including food aid. One had positive results – including greater likelihood of viral suppression – though only a portion of the participants received food support (Muñoz et al., Citation2011), while others did not report any significant results from food assistance (Rich et al., Citation2012; Talisuna-Alamo et al., Citation2012). In a final study, participants in a combined HES intervention, including monthly food support for those with severe hunger, reported better adherence than non-participants (Bezabih, Citation2016).

Educational support

Of the two studies of education support, one was high quality and the other medium quality (). The first found that HIV positive adults in a combined intervention in Uganda who received school fee support for their children were less likely to be LTFU and had a lower likelihood of mortality than intervention participants not getting this support (Talisuna-Alamo et al., Citation2012). The other found that support with school fees for HIV-positive adolescents in South Africa was not predictive of higher reported ART adherence (Cluver et al., Citation2016).

Protection interventions

Savings (individual and group)

Three studies assessed savings support on these outcomes (). Two were medium quality, and one was low quality. An intervention in Ethiopia, including group savings and other HES components, was associated with better self-reported adherence than a comparison group (Bezabih, Citation2016). In contrast, participants in another program in Ethiopia with several health and HES services, including group savings and lending, unexpectedly reported lower levels of adherence and more opportunistic infections than the comparison group, though the participants’ mortality rate declined during the intervention period (Okello et al., Citation2013). The reason for these discordant findings is unclear though they may be due, in part, to the study’s sampling strategy. A third study in Zambia compared a combined HES and adherence support intervention that included individual savings, to adherence support alone, finding no difference in self-reported adherence between study arms (Masa, Citation2016).

Financial capabilities education and training

Only one medium quality study evaluated financial training (). Participants in an intervention in Zambia that provided financial education, other HES support, and adherence counseling, were no more likely to report ART adherence than those receiving adherence counseling only (Masa, Citation2016).

Income generation

Eight studies were identified that examined income generating activities (IGAs) (). Two studies were medium-high quality, while five were medium, and one was low quality. Two studies assessed IGAs independently: one found no association between participation in IGAs and retention in care in Cambodia (Daigle et al., Citation2015), while a qualitative study in Zambia found that IGAs motivated ART adherence (Sanjobo et al., Citation2008).

Six more studies evaluated the effectiveness of combined interventions, some of which had explicit health components. Two studies of integrated health and HES support, including IGAs, in Uganda and Ethiopia found no association with self-reported experiences of disease and ART adherence, respectively (Abimanyi-Ochom et al., Citation2013; Masa, Citation2016). A third study, in Ethiopia, unexpectedly found negative associations between participation in an HES and health intervention and self-reported ART adherence and opportunistic infections, though improvements were seen in participants’ mortality rate during the intervention period (Okello et al., Citation2013). As noted above, these findings may be due, in part, to the study's sampling approach.

In contrast, an experimental study of an IGA and microcredit intervention in Kenya found positive results for CD4 counts and viral suppression (Weiser et al., Citation2015). A qualitative sub-study found ART adherence was improved by reducing food insecurity, increasing access to transport, and improving social capital and a desire to prioritize health (Weiser et al., Citation2017). The preceding feasibility study of the same intervention reported only positive trends for CD4 counts (Pandit et al., Citation2010).

Promotion interventions

Microcredit

Seven studies evaluated care and treatment outcomes of microcredit programs (). Of these, one study was high quality, while two were medium-high, and four were medium quality. All but one study found positive results, with no negative findings. Only two studies looked at microcredit independently, finding that that receipt of a loan was associated with better appointment adherence in Cambodia (Daigle et al., Citation2015), and lower LTFU and reduced mortality in Uganda (Talisuna-Alamo et al., Citation2012).

An experimental study of a combined microcredit and IGA intervention in Kenya, also cited in the section on IGAs, found promising results related to CD4 and viral suppression (Weiser et al., Citation2015); a related qualitative study highlighted the pathways by which the intervention affected these outcomes (Weiser et al., Citation2017). The preceding feasibility study was not powered to detect significant differences in CD4 counts but found positive trends (Pandit et al., Citation2010). Two studies that combined ART adherence support and HES, including microcredit, yielded positive findings in relation to self-reported adherence (Arrivillaga et al., Citation2014), virologic suppression, and mortality (Muñoz et al., Citation2011). However, in the latter study only a fraction of intervention participants received microcredit services, therefore the results may be unrelated to this intervention component.

Vocational and entrepreneurial training

Three studies of varied quality assessed entrepreneurial training interventions; one was high quality, one medium quality, and one low quality (). Two evaluated entrepreneurial training as components of larger interventions aimed at supporting ART adherence. One, conducted with females in Colombia, found that self-reported adherence improved over the intervention period (Arrivillaga et al., Citation2014); the other found entrepreneurial training was independently associated with lower LTFU and reduced mortality among adult PLHIV in Uganda (Talisuna-Alamo et al., Citation2012). Similarly, participants in an intervention in Ethiopia which included entrepreneurial training and other HES support, reported better adherence than a comparison group (Bezabih, Citation2016).

Employment support

Only one high quality study evaluated the effectiveness of employment support (). A community-based ART program in Uganda provided additional socioeconomic support to clients, as needed, including employment with the program for some. The study found that employment support was independently associated with lower LTFU and lower mortality (Talisuna-Alamo et al., Citation2012).

Ongoing studies

One ongoing study was also identified which is assessing the effectiveness of an integrated HES and ART adherence intervention, compared to adherence support alone, for younger adolescents in Uganda. The HES intervention combines savings, financial capabilities training, and entrepreneurial training, and will increase the evidence base for these interventions, and may support the identification of stronger trends, which are currently lacking. However, without a factorial design the relative contributions of these different intervention components will not be measured ().

Table 15. Ongoing studies of retention and adherence outcomes.

Discussion

As the universal test and treat approach is implemented globally, more individuals are initiating ART immediately following their HIV diagnosis, regardless of clinical stage. Keeping new initiates in care and adherent to ART is essential to their health and to epidemic control. Yet people in resource constrained contexts face a wide range of barriers to care. Economic barriers such as transportation costs, lost opportunity costs, and food insecurity threaten ongoing care and treatment objectives and must be addressed to ensure progress toward the UNAIDS 90-90-90 goals. For those who are economically insecure, HES interventions are increasingly integrated into adherence-focused interventions to mitigate these barriers. Thirty-eight citations were identified that evaluated HES interventions and ongoing care and treatment outcomes. This research represents evidence from 20 countries, though 63% of the studies were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa.

Because food insecurity is highly correlated with poverty and is a known barrier to ART adherence (Young et al., Citation2014), food support is an intuitive type of assistance for improving care and treatment outcomes. The quality associated with the literature on food assistance is mixed, though the studies collectively indicate this support – particularly monthly food rations – is associated with improved medication pick-up, appointment attendance and self-reported adherence. Few studies measured clinical outcomes, but these results were less conclusive. In addition, some studies targeted highly vulnerable populations for this support, which could differentially affect health outcomes. The evidence for CCTs is also primarily positive for improved appointment attendance and medication pick-up, but null for most clinical outcomes (CD4 and viral load) measured.

The smaller evidence base for financial incentives highlights a mix of positive and null results, possibly indicating that the ongoing nature of CTs is more effective in supporting these ongoing care and treatment outcomes. Although studies of transportation assistance primarily reported positive outcomes, most assessed the effects of combined interventions, indicating that transportation assistance may be a beneficial component of adherence-focused interventions.

The overall quality of evidence for IGAs is moderate, and most studies relied on relatively small sample sizes, and assessed combined interventions. These studies reveal inconsistent findings which may be partially explained by the wide variation in the interventions themselves, and in the specific outcomes measured. Microcredit studies also primarily assessed combined interventions and relied on small samples sizes, though positive trends spanned care seeking, as well as clinical outcomes of CD4 counts, viral suppression, and mortality. Unlike the literature on microcredit for HIV prevention outcomes, however, none of these studies reported effects on violence or increased vulnerability, which may warrant further exploration. Evidence for UCTs, education support, financial education, savings, entrepreneurial training, and employment support is too limited and varied to identify clear trends.

Half of the studies in this paper relied on self-reported data for at least some outcomes, while clinical record data (e.g., visit history, medication pick up and similar measures) were assessed in 42%, and clinical outcome data (CD4 count and viral load) were assessed in nearly 32% of the studies (eight studies looked at multiple outcomes that spanned these larger outcome categories). Compared to self-reported outcomes and clinical record data on visit history and medication pick-up, where results were consistently positive with few exceptions, CD4 count and viral suppression outcomes were primarily null. While self-reported measures of adherence and retention are subject to bias, the clinical record data provide greater confidence in positive behavioral trends. However, future research using longer intervention and follow-up periods is needed to confirm whether HES can have an effect beyond behavior change and improve clinical health outcomes.

Nearly 82% of studies in this part of the series were based on or included provision components, while only 24 and 21%, respectively, included protection and promotion interventions. The comparatively limited data on protection and promotion interventions restricts our understanding of their value in the context of ongoing HIV care and treatment. In many contexts, the need for ongoing resources makes some provision interventions less viable outside of a government supported program. Given the lifelong nature of ART, prioritizing research on protection and promotion interventions will improve our understanding of the effectiveness of program approaches that have the potential to support long-lasting care and treatment benefits. While most of the included studies assessed the direct associations of intervention components on the outcomes of interest, nearly 32% only assessed the effectiveness of integrated interventions, preventing a clear understanding of the individual association between each intervention component and these outcomes.

The study limitations are discussed in greater detail in the first paper in this series (Swann, Citation2018a). They include the introduction of reviewer bias in the inclusion of a quality assessment, which was mitigated through the creation of a structured codebook and using two reviewers. Categorization of studies into each intervention and outcome was done through a thorough assessment of the study details; when methodological details were limited, categorization was based careful review of available information. Given the variation in study characteristics, there may be additional trends which were not identified from the analytical framework used.

Conclusions

The evidence for food assistance – particularly monthly food rations – as well as CCTs shows a positive association with ongoing care and treatment outcomes, signifying that these types of HES support may be an important component of adherence efforts in many contexts. Transportation assistance, IGAs and microcredit also highlight positive trends, though evidence quality is moderate and based heavily on combined interventions. Overall, the evidence is more conclusive for self-reported and clinically-documented behaviors, while outcomes related to CD4 counts and viral suppression were mostly null.

Additional research is needed to understand possible effects of protection and promotion interventions on these outcomes. Stronger research designs are needed to more fully understand the effect of HES interventions on retention and adherence, particularly when they are provided within an integrated package of services. Research and evaluation efforts going forward should incorporate clinical data on CD4 counts and viral load, where possible, to strengthen findings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the excellent work of Cheryl Tam, formerly of FHI 360, in screening and assessing the quality of articles included in this review. We are grateful to several FHI 360 colleagues, including Whitney Moret for her contributions to this manuscript, Allison Burns and Tamara Fasnacht for their support in the literature search, and Jenae Tharaldson for her assistance preparing the manuscript. Finally, we would like to thank the researchers, donors and practitioners who participated in the half-day consultative meeting held on July 13, 2016 for their thoughtful input and expertise on this topic.

Disclosure statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

ORCID

Mandy Swann http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0348-8024

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Green (positive) = positive findings on one or more primary outcome of interest and no negative findings; blue (null) = no effect/association was observed on primary outcome(s) or study was under-powered; yellow (mixed) = a mix of positive and negative results on primary outcomes of interest; and red (negative) = negative findings on one or more primary outcomes of interest and no positive findings.

References

- Abimanyi-Ochom, J., Lorgelly, P., Hollingsworth, B., & Inder, B. (2013). Does social support in addition to ART make a difference? Comparison of households with TASO and MOH PLWHA in central Uganda. AIDS Care, 25(5), 619–626. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.726337

- Adato, M., & Bassett, L. (2012). Social protection and cash transfers to strengthen families affected by HIV and AIDS. In M. Adato, & L. Bassett (Eds.), Social protection and cash transfers to strengthen families affected by HIV and AIDS (pp. 1–3). Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Anema, A., Vogenthaler, N., Frongillo, E. A., Kadiyala, S., & Weiser, S. D. (2009). Food insecurity and HIV/AIDS: Current knowledge, gaps, and research priorities. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 6(4), 224–231.

- Arrivillaga, M., Salcedo, J. P., & Pérez, M. (2014). The IMEA project: An intervention based on microfinance, entrepreneurship, and adherence to treatment for women with HIV/AIDS living in poverty. AIDS Education and Prevention, 26(5), 398–410. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2014.26.5.398

- Bezabih, T. (2016). Urban HIV and AIDS nutrition and food security project economic strengthening key outcome level results. Addis Ababa: WFP Ethiopia Country Office.

- Byron, E., Gillespie, S., & Nangami, M. (2008). Integrating nutrition security with treatment of people living with HIV: Lessons from Kenya. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 29(2), 87–97.

- Cantrell, R. A., Sinkala, M., Megazinni, K., Lawson-Marriott, S., Washington, S., Chi, B. H., … Stringer, J. S. (2008). A pilot study of food supplementation to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among food-insecure adults in Lusaka, Zambia. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 49(2), 190–195. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818455d2

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Understanding the HIV Care Continuum.

- Cluver, L. D., Operario, D., Lane, T., & Kganakga, M. (2011). “I can’t go to school and leave her in so much pain”: educational shortfalls among adolescent “young carers” in the South African AIDS epidemic. Journal of Adolescent Research, 27(5), 581–605. doi: 10.1177/0743558411417868

- Cluver, L. D., Toska, E., Orkin, M., Meincka, F., Hodesa, R., Yakubovicha, A., & Sherr, L. (2016). Achieving equity in HIV-treatment outcomes: Can social protection improve adolescent ART-adherence in South Africa? AIDS Care, 28(NO. S2), 1–10.

- Daigle, G. T., Jolly, P. E., Chamot, E. A. M., Ehiri, J., Zhang, K., Khan, E., & Sou, S. (2015). System-level factors as predictors of adherence to clinical appointment schedules in antiretroviral therapy in Cambodia. AIDS Care, 27(7), 836–843. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1024098

- Deb, A., & Kubzansky, M. (2012). Bridging the gap: The business case for financial capability. New York: Monitor Group and Citi Foundation.

- DFID. (2014). Assessing the strength of evidence. London: DFID.

- Egge, K., & Strasser, S. (2006). Measuring the impact of targeted food assistance on HIV/AIDS-related beneficiary groups: Monitoring and evaluation indicators. In S. E. Gilespie (Ed.), AIDS, poverty, and hunger (pp. 305–324). Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- El-Sadr, W., Branson, B., & Beauchamp, G. (2015). Effect of financial incentives on linkage to care and viral suppression: HPTN 065. Seattle: CROI.

- Farber, S., Tate, J., Frank, C., Ardito, D., Kozal, M., Justice, A. C., & Braithwaite, R. S. (2013). A study of financial incentives to reduce plasma HIV RNA among patients in care. AIDS and Behavior, 17(7), 2293–2300. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0416-1

- Foster, C., McDonald, S., Frize, G., Ayers, S., & Fidler, S. (2014). “Payment by results”--financial incentives and motivational interviewing, adherence interventions in young adults with perinatally acquired HIV-1 infection: A pilot program. AIDS Patient Care and STDS, 28(1), 28–32. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0262

- Guo, Y., Li, X., & Sherr, L. (2012). The impact of HIV/AIDS on children’s educational outcome: A critical review of global literature. AIDS Care, 24(8), 993–1012. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.668170

- Haber, N., Tanser, F., Herbst, K., Pillay, D., & Barnighausen, T. (2015). Negative impact of South Africa’s disability grants on HIV/AIDS recovery. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18(Suppl 4), 45–45.

- Haberer, J. E., Sabin, L., Amico, K. R., Orrell, C., Galarraga, O., Tsai, A. C., … Bangsberg, D. R. (2017). Improving antiretroviral therapy adherence in resource-limited settings at scale: A discussion of interventions and recommendations. Journal of The international Aids Society, 20(1), 1–15. doi: 10.7448/ias.20.1.21371

- Heise, L., Lutz, B., Ranganathan, M., & Watts, C. (2013). Cash transfers for HIV prevention: Considering their potential. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16, 18615. doi: 10.7448/ias.16.1.18615

- Ivers, L. C., Chang, Y., Gregory Jerome, J., & Freedberg, K. A. (2010). Food assistance is associated with improved body mass index, food security and attendance at clinic in an HIV program in central Haiti: A prospective observational cohort study. AIDS Research and Therapy, 7, 33. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-33

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2014). 90-90-90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2017). Ending AIDS: Progress towards the 90–90–90 targets global AIDS update. Geneva: UNAIDS.

- Jones, C. (2011). “If I take my pills I’ll go hungry”: the choice between economic security and HIV/AIDS treatment in grahamstown, South Africa. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 35(1), 67–80. doi: 10.1111/j.2153-9588.2011.01067.x

- Kalichman, S. C., Hernandez, D., Cherry, C., Kalichman, M. O., Washington, C., & Grebler, T. (2014). Food insecurity and other poverty indicators among people living with HIV/AIDS: Effects on treatment and health outcomes. Journal of Community Health, 39(6), 1133–1139.

- Kharsany, A. B. M., & Karim, Q. A. (2016). HIV infection and AIDS in Sub-saharan Africa: Current status, challenges and opportunities. The Open AIDS Journal, 10, 34–48. doi: 10.2174/1874613601610010034

- Lankowski, A. J., Siedner, M. J., Bangsberg, D. R., & Tsai, A. C. (2014). Impact of geographic and transportation-related barriers on HIV outcomes in sub-saharan Africa: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 18(7), 1199–1223. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0729-8

- Martinez, H., Palar, K., Linnemayr, S., Smith, A., Derose, K. P., Ramirez, B., … Wagner, G. (2014). Tailored nutrition education and food assistance improve adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: Evidence from Honduras. AIDS and Behavior, 18(Suppl 5), S566–S577. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0786-z

- Masa, R. D. (2016). Food security and antiretroviral therapy adherence among people living with HIV in Lundazi District, Zambia: a pilot study (Doctoral dissertation). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

- McCoy, S., Njau, P., Fahey, C., Czaicki, N., Kapologwe, N., Kadiyala, S., … Padian, N. (2016, July 18–22). A randomized study of short-term conditional cash and food assistance to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among food insecure adults with HIV infection in Tanzania. Paper presented at the 21st international AIDS conference, Durban, South Africa.

- McNairy, M., Lamb, M., Gachuhi, A., Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha, H., Burke, S., Mazibuko, S. … Group, L. H. S. (2016). LINK4HEALTH: a cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of a combination strategy for linkage to and retention in HIV care in Swaziland. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 19(Suppl 15), 66–66.

- Metsch, L. R., Feaster, D. J., Gooden, L., Matheson, T., Stitzer, M., Das, M., … del Rio, C. (2016). Effect of patient navigation with or without financial incentives on viral suppression among hospitalized patients with HIV infection and substance use: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, 316(2), 156–170. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8914

- Miller, C., & Tsoka, M. G. (2012). ARVs and cash too: Caring and supporting people living with HIV/AIDS with the Malawi social cash transfer. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 17(2), 204–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02898.x

- Muñoz, M., Bayona, J., Sanchez, E., Arevalo, J., Sebastian, J. L., Arteaga, F., & Shin, S. (2011). Matching social support to individual needs: A community-based intervention to improve HIV treatment adherence in a resource-poor setting. AIDS and Behavior, 15, 1454–1464.

- Nsigaye, R., Wringe, A., Roura, M., Kalluvya, S., Urassa, M., Busza, J., & Zaba, B. (2009). From HIV diagnosis to treatment: Evaluation of a referral system to promote and monitor access to antiretroviral therapy in rural Tanzania. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 12, 31. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-31

- Nyamathi, A., Hanson, A. Y., Salem, B. E., Sinha, S., Ganguly, K. K., Leake, B., … Marfisee, M. (2012). Impact of a rural village women (asha) intervention on adherence to antiretroviral therapy in southern India. Nursing Research, 61(5), 353–362. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31825fe3ef

- Okello, F. O., Stuer, F., Kidane, A., & Wube, M. (2013). Saving the sick and improving the socio-economic conditions of people living with HIV in Ethiopia through traditional burial groups. Health Policy and Planning, 28(5), 549–557. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs097

- Palar, K., Napoles, T., Hufstedler, L. L., Seligman, H., Hecht, F., Madsen, K., … . Weiser, S. (2016, May 9–11). Comprehensive and medically appropriate food support is associated with improved ART adherence and HIV outcomes. Paper presented at the 11th international conference on HIV treatment and prevention adherence, Fort Lauderdale, FL.

- Pandit, J. A., Sirotin, N., Tittle, R., Onjolo, E., Bukusi, E. A., & Cohen, C. R. (2010). Shamba maisha: A pilot study assessing impacts of a micro-irrigation intervention on the health and economic wellbeing of HIV patients. BMC Public Health, 10, 245. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-245

- Phaswana-Mafuya, N., Peltzer, K., & Petros, G. (2009). Disability grant for people living with HIV/AIDS in the eastern cape of South Africa. Social Work in Health Care, 48(5), 533–550. doi: 10.1080/00981380802595156

- Rich, M. L., Miller, A. C., Niyigena, P., Franke, M. F., Niyonzima, J. B., Socci, A., … Binagwaho, A. (2012). Excellent clinical outcomes and high retention in care among adults in a community-based HIV treatment program in rural Rwanda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 59(3), e35–e42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824476c4

- Rigsby, M. O., Rosen, M. I., Beauvais, J. E., Cramer, J. A., Rainey, P. M., O’Malley, S. S., … Rounsaville, B. J. (2000). Cue-dose training with monetary reinforcement: Pilot study of an antiretroviral adherence intervention. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 15(12), 841–847.

- Rutherford, S. (2000). The poor and their money. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Sanjobo, N., Frich, J. C., & Fretheim, A. (2008). Barriers and facilitators to patients’ adherence to antiretroviral treatment in Zambia: A qualitative study. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 5(3), 136–143. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2008.9724912

- Snilstveit, B., Vojtkova, M., Bhavsar, A., Stevenson, J., & Gaarder, M. (2016). Evidence & gap maps: A tool for promoting evidence informed policy and strategic research agendas. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 79, 120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.05.015

- Solomon, S. S., Srikrishnan, A. K., Vasudevan, C. K., Anand, S., Kumar, M. S., Balakrishnan, P., … Lucas, G. M. (2014). Voucher incentives improve linkage to and retention in care among HIV-infected drug users in chennai, India. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 59(4), 589–595. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu324

- Swann, M. (2018a). Economic strengthening for HIV prevention and risk reduction: A review of the evidence. AIDS Care. doi:10.1080/09540121.2018.1479029

- Swann, M. (2018b). Economic strengthening for HIV testing and linkage to care: a review of the evidence. AIDS Care. doi:10.1080/09540121.2018.1476665

- Talisuna-Alamo, S., Colebunders, R., Ouma, J., Sunday, P., Ekoru, K., Laga, M., … Wabwire-Mangen, F. (2012). Socioeconomic support reduces nonretention in a comprehensive, community-based antiretroviral therapy program in Uganda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 59(4), e52–e59. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318246e2aa

- Tirivayi, N., Koethe, J. R., & Groot, W. (2012). Clinic-based food assistance is associated with increased medication adherence among HIV-infected adults on long-term antiretroviral therapy in Zambia. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 3(7), 171.

- Tolley, E., Taylor, J., Pack, A., Greene, E., Stanton, J., El-Sadr, W., & Gamble, T. (2016, October 17–21). Role of financial incentives along the ART adherence continuum: A qualitative analysis from the HPTN 065 study. Paper presented at the HIV research For prevention, Chicago.

- Weiser, S. D., Bukusi, E. A., Steinfeld, R. L., Frongillo, E. A., Weke, E., Dworkin, S. L., … Cohen, C. R. (2015). Shamba maisha: Randomized controlled trial of an agricultural and finance intervention to improve HIV health outcomes. AIDS, 29(14), 1889–1894. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000000781

- Weiser, S. D., Hatcher, A. M., Hufstedler, L. L., Weke, E., Dworkin, S. L., Bukusi, E. A., … Cohen, C. R. (2017). Changes in health and antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected adults in Kenya: Qualitative longitudinal findings from a livelihood intervention. AIDS and Behavior, 21, 415–427. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1551-2

- Weiser, S. D., Wolfe, W., Bangsberg, D. R., Thior, I., Gilbert, P., Makhema, J., … Essex, M. (2003). Barriers to antiretroviral adherence for patients living with HIV infection and AIDS in Botswana. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 34(3), 281–288.

- Woller, G. (2011). Livelihood and food security conceptual framework. Washington, DC: FHI 360, LIFT.

- Yotebieng, M., Thirumurthy, H., Moracco, K. E., Kawende, B., Chalachala, J. L., Wenzi, L. K., … Behets, F. (2016). Conditional cash transfers and uptake of and retention in prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission care: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet HIV, 3(2), e85–e93. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3018(15)00247-7

- Young, S., Wheeler, A., McCoy, S., & Weiser, S. D. (2014). A review of the role of food insecurity in adherence to care and treatment among adult and pediatric populations living with HIV and AIDS. AIDS and Behavior, 18(0 5), 505–515. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0547-4

- Zaveri, S. (2008). Economic strengthening and children affected by HIV/AIDS in Asia: Role of communities. Joint Learning Initiative on Children and AIDS [JLICA]. Retrieved from http://ovcsupport.org/wpcontent/uploads/Documents/Economic_Strengthening_and_children_affected_by_HIV_in_Asia_Role_of_Communities_1.pdf.