ABSTRACT

People living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in China experience significant psychological distress, due to high rates of stigma and low availability of mental health resources. Recently diagnosed Chinese PLWHA who are men who have sex with men (MSM) are particularly vulnerable to distress, facing both HIV and sexual orientation stigma. Reducing distress and enhancing psychological resilience is critical in promoting wellbeing. However, no research to date has examined evidence-based interventions to reduce psychological symptoms and improve resilience in this population. Based on qualitative research on their mental health needs, we developed a culturally tailored, brief 3-session CBT skills-based intervention for integration into primary care [Yang, J. P., Simoni, J., Cheryan, S., Shiu, C., Chen, W., Zhao, H., & Lu, H. (2018). The development of a brief distress reduction intervention for individuals recently diagnosed with HIV in China. Cognitive Behavioral Practice, 25(2), 319–334. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2017.08.002]. The intervention includes cognitive restructuring to address depressive thought patterns, behavioral activation to decrease isolation, and paced breathing to reduce anxiety. We conducted a pilot Type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial assessing pre–post mental health outcomes as well as feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness information. Ten recently diagnosed MSM completed the research protocol of three individual weekly sessions. Paired-samples t tests demonstrated significant reduction in HIV-related distress, depression, problems with adjustment, as well as improvements in resilience, and perceived social support. Participants and community advisory board members found the intervention highly acceptable, appropriate, and feasible. Preliminary data from the first known study examining a psychological intervention with evidence-based components for recently diagnosed Chinese MSM suggests that this brief intervention may be useful for reducing distress and promoting resilience.

Introduction

People living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in China experience significant mental health distress, in part due to high rates of stigma and low availability of mental health resources (Yang et al., Citation2015). HIV stigma is prevalent; for example, a 2008 survey of HIV attitudes in over 6000 urban residents found that 48% of respondents would not eat with someone who had HIV and 30% thought children with HIV should not be allowed to attend the same schools as children without HIV (China AIDS Media Partnership, Citation2008).

While the overall prevalence of HIV in China is stabilizing (UNAIDS, Citation2015), rates of HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) in China are increasing (Choi et al., Citation2003). A study published in 2007 that assessed MSM independently in the three years prior found that HIV prevalence was 0.4% in 2004, 4.6% in 2005, and 5.8% in 2006, indicating rising prevalence of HIV among MSM (Ma et al., Citation2007). Governmental reports indicate that from 2005 to 2015, the HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men increased from about 1.5% to about 8.5% in 2015 (UNAIDS, Citation2015). Of the new cases diagnosed each year, MSM transmission increased from accounting for 2.5% in 2006 to 25.8% in 2014 (UNAIDS, Citation2015). Data reported in 2009 indicated that MSM made up 11.1% of all HIV/AIDS cases in China (Wong et al., Citation2009).

In addition to HIV stigma, MSM in China face intense sexual orientation related stigma (Feng, Wu, & Detels, Citation2010; Li et al., Citation2012). In a survey of self-identified gays and lesbians (N = 1000; HIV status not assessed), 40.5% reported having at least one suicide attempt in their lifetime (Zhang & Chu, Citation2005). Due to discrimination, MSM in China remain a largely hidden population. In a qualitative study with 46 MSM, participants detailed a primary stressor as pressure from families due to strong Chinese traditions to marry and have children (Feng et al., Citation2010). The emphasis on the Confucian custom of filial piety has been further intensified in the current social climate under the one-child policy, where many MSM are their parents’ only hope for grandchildren. As a result, many MSM marry women to have children, leading to increased negative emotion such as shame and anxiety due to secrecy (Choi, Gibson, Han, & Guo, Citation2004). Some sources suggest that 80% of gay men in China are married to women (Kaufman & Jing, Citation2002). For MSM who are HIV-positive, this practice can lead to increased transmission risk, as they simultaneously have sex with men as well as unprotected sex with their wives (who are often unaware of either their HIV or MSM status; Qian, Vermund, & Wang, Citation2005).

Only one peer-reviewed published study of mental health focused on HIV-positive MSM in China was located, which reported descriptive data of 47.8% of MSM on ART were smokers in the last year (Xu et al., 2014 in Chinese, as cited in Niu, Luo, Liu, Silenzio, & Xiao, Citation2016).

While mental health needs are high, psychological resources are few. An epidemiological survey of N = 63,004 estimated that 91.8% of individuals with a diagnosis of any mental disorder never seek help; of those with psychotic disorders, 27.6% never sought help (Phillips et al., Citation2009). The gap in access to care results from a combination of cultural attitudes towards mental illness, specifically the high rate of stigma present juxtaposed against the low availability of supply of resources.

The majority of mental health professionals in China are psychiatrists or psychiatric nurses; there are few clinical psychologists, social workers, or otherwise licensed mental health professionals. In 2004, there were 16,103 licensed psychiatrists and psychiatric registrars, effectively 1.24 per population of 100,000, and 24,793 licensed psychiatric nurses, equating to 1.01 per 100,000 (WHO, Citation2005). Mental health resources are limited in China compared to the global average mental health workforce of 4.15 psychiatrists and 12.97 psychiatric nurses per 100,000 (and certainly the US rate of 55.6 psychiatrists per 100,000; US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Citation2010).

Not surprisingly, intervention studies in China focusing on behavioral strategies to improve the mental health of MSM and promote could not be found. Given the disparity between need among PLWHA, especially those who are MSM, and the availability of treatment, research is necessary on psychosocial interventions to address this gap.

The Psychology Toolbox, a brief cognitive–behavioral skills based intervention was previously designed to reduce distress and promote adaptive coping and resilience for individuals recently diagnosed with HIV and to be implemented in a primary care setting (see Yang et al., Citation2018). Adaptive coping refers to adopting active strategies to manage stress, such as reappraising problems and regulating emotions (Thompson et al., Citation2010). Use of adaptive coping facilitates development of resilience, defined as “attaining desirable social and emotional adjustment”, in the face of HIV (Betancourt, Meyers-Ohki, Charrow, & Hansen, Citation2013; Luthar, Citation1993). The Psychology Toolbox teaches three skills, one in each session, to promote adaptive coping. First, cognitive restructuring is taught through the use of an automatic thought record in order to promote realistic reappraisal of situations, which can decrease arousal and facilitate problem solving. Second, participants are taught to examine behavioral trigger response avoidance patterns in their lives order to engage in alternative coping (TRAP/TRAC), for behavioral activation, which reduces depression. Finally, paced breathing that increases vagal tone to increase parasympathetic nervous system activation relative to sympathetic nervous system activation is taught as in-the-moment anxiety reduction skill to improve emotion regulation. In this study, a pilot trial is conducted to test this intervention with recently HIV diagnosed MSM, a population that is particularly at risk for psychological distress.

This pilot study employs Curran, Bauer, Mittman, Pyne, and Stetler’s (Citation2012) framework for a Type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial that combines a priori, testing effects of an intervention on outcomes of interest while simultaneously collecting data on implementation of the intervention. Specifically, mental health outcomes of distress, depression, adjustment, coping, and social support are assessed as well as implementation outcomes of acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness. Acceptability, assessed at the individual consumer/patient level refers to satisfaction with the intervention; feasibility, assessed at the individual provider/stakeholder level refers to suitability or practicability of the intervention; and appropriateness, assessed at the individual consumer and provider level refers to perceived fit, relevance, and suitability (Proctor et al., Citation2011). This Type 1 hybrid trial design allows for more rapid translational gains as well as the gathering of useful information to assist in uptake of the intervention for future research (Curran et al., Citation2012). Implementation outcomes are examined with a mixed methods design with simultaneous goals of convergence to examine if participants provide similar answers qualitatively and quantitatively as well as complementarity to examine related questions of evaluation of outcomes and process (Aarons, Fettes, Sommerfeld, & Palinkas, Citation2012; Powell et al., Citation2012). Intervention participants will provide qualitative and quantitative data for convergence and complementarity, and Community Advisory Board members will provide qualitative data for complementarity in order to better understand and overcome barriers to implementation.

Methods

Procedures

Data were collected from June to August 2015 at Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center (SPHCC), a premier infectious disease treatment center. Institutional Review Boards at University of Washington and SPHCC approved all study procedures. Eligibility criteria were a) male; b) diagnosed with HIV within the last 12 months; c) acquired HIV via having sex with men; d) at least 18 years of age; e) receiving care at SPHCC; f) willing and capable of attending intervention sessions at SPHCC. An advertisement for the research study with contact information for research staff was posted in the waiting room. Healthcare providers at SPHCC also provided referrals and interested individuals were referred to research staff. After the study was explained, written informed consent was obtained from those willing to participate, and the first meeting began immediately or was scheduled for a more convenient date. The two subsequent sessions (3 in total) were each scheduled for approximately a week apart, coinciding with participants’ primary care visits whenever possible. Ten participants completed the study protocol.

The intervention was delivered by the first author, a sixth year doctoral candidate in clinical psychology who is fluent in Mandarin and a developer of the Psychology Toolbox intervention (Yang et al., Citation2018). All sessions were audio recorded with participants’ permission in order for fidelity checks to be performed to ensure that session contents were delivered. After sessions were complete, two research assistants listened to recordings independently to ensure that the critical skill in each session was taught, that homework was assigned, and homework was reviewed in sessions two and three.

At baseline and immediately post intervention (4 weeks), participants filled out an approximately 1 hour-long paper-and-pencil assessment survey with a separate research staff assessor. At the end of the last intervention session, the interventionist administered a semi-structured exit interview that lasted between 15–30 minutes. Participants were reimbursed RMB 150 (∼ USD 25) for each study session, which is typical for participation at SPHCC and not considered coercive. One day prior to each intervention session, a reminder text message was sent to participants.

Measures

Participants responded to standard socio-demographic questions of age, sex, education, employment, income, marital status, and sex of sexual partner. Research staff took detailed notes on participants’ adherence to appointment times, what portion of the session they were present for, and whether they completed homework. Intervention outcomes of mental health, and post-intervention assessment of acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility are described below. Measure reliability is reported in .

Table 1. Reliability Cronbach’s α (Citation1951) of measures used.

Outcome measures

Patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9)

The PHQ-9 is a brief measure of depression severity for use in primary care settings (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, Citation2001); the Chinese version has been validated as well (Yeung et al., Citation2008).

Brief adjustment scale (BASE -6)

The BASE-6 (Peterson et al., Citationunder review) is a measure of problems in general psychological adjustment that assesses emotion distress (depression, anxiety, and anger) and related interference (impact on self-esteem, personal relationships, and occupational functioning). This measure was translated and back translated (Brislin, Citation1970; WHO, Citation2015) for use in this study.

HIV distress and coping questionnaire

This questionnaire was developed for this study to assess frequency and intensity of HIV-related distress as well as coping skills to deal with the HIV distress. Higher scores on the distress subscale indicate more distress, whereas higher scores on the coping subscale correspond with more ability to cope.

Medical outcomes study – social support scale

The Chinese adaptation (Yu, Lee, & Woo, Citation2004) of the Medical Outcomes Study – Social Support Scale (Sherbourne & Stewart, Citation1991) is a psychometrically validated measure of perceived social support for patients living with chronic illness, and has been previously used with HIV-positive patients in China (e.g., Yang et al., Citation2015; Yu et al., Citation2015).

Implementation measures

As this was a pilot Type I Trial (Curran et al., Citation2012) designed to assess preliminary efficacy as well as feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness of implementing the intervention in a primary care setting, we also qualitatively and quantitatively asked participants for their perspectives on the intervention. All implementation measures were translated and back-translated (WHO, Citation2015) for this study as they have not been previously used in Chinese. A Community Advisory Board of nurses, physicians, a caseworker, a hospital administrator, and Red Ribbon Society (an HIV/AIDS non-governmental organization) peer leaders who were on site at the primary care ward (e.g., in the waiting room, seeing and referring patients to the study) was consulted for expert opinions on the feasibility and appropriateness of the intervention. These members were chosen as they represent stakeholders invested in the research population, who will also influence potential future implementation efforts (Berg, Citation2004).

Client satisfaction questionnaire (CSQ-18)

The CSQ is a global measure assessing satisfaction or acceptability with services received, and is well suited for adaptation to refer to the particular intervention of interest (Attkisson & Zwick, Citation1982).

Acceptability, feasibility and appropriateness scale (AFAS)

The AFAS (Gopalan, Citation2016; Lyon, Citation2012) assesses intervention, program, or training acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness.

Acceptability of intervention measure (AIM)

The AIM is 13-item measure of acceptability of interventions (Henninger, Citation2010), in which the name of the intervention, “Psychology Toolbox”, and “individuals recently diagnosed with HIV” as the target population were supplanted.

Treatment acceptability questionnaire (TAQ)

The first item of the Treatment Acceptability Questionnaire (Hunsley, Citation1992) was used as an overall acceptability rating, “Overall, how acceptable do you find the intervention to be” on a scale of 1 (Very Unacceptable) to 7 (Very Acceptable).

Qualitative exit interview questions

A semi-structured qualitative exit interview was designed to assess familiarity with intervention concepts, skills/knowledge acquisition, and perspectives on the intervention. Open-ended questions for knowledge checks included “In your own words, what was the intervention about?” Each skill was covered independently where participants were asked to explain their understanding of the skill, how to use it, and what circumstances they would use it under. Participants were also queried about likes and dislikes, recommended changes, and opinions about content and process (location, frequency, duration of sessions).

Analytic procedures

Descriptive statistics were conducted to summarize characteristics at baseline. Paired samples t tests were conducted to assess differences on each measure of mental health, distress, and coping before and after the intervention. Cohen’s dz effect sizes for one-sample dependent t test measurements were calculated (Lakens, Citation2013).

Qualitative interviews were transcribed and examined using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) as used in previous qualitative implementation research (Dittmann & Jensen, Citation2014; Murray et al., Citation2014). Transcriptions were kept in Chinese for analysis and coding to preserve participants’ wording; representative quotes were translated into English for use in this manuscript. The lead author and three research assistants who are Chinese-English bilinguals analyzed the data. Transcripts were reviewed thoroughly via listening to the interview recordings, taking notes on data transcripts, and reviewing notes of key points taken by the facilitator during interviews to establish familiarity. Themes relevant to implementation were then summarized.

Results

Participants

Due to the small sample size (N = 10), median demographics are reported. The median number of days since diagnosis was 66 days (just over 2 months), the median age of participants is 26.5 years (SD = 8.0). The sample was overall highly educated, with 70% having graduated from professional/vocational training school, college, or graduate school. No one in the sample was unemployed. Eighty percent of the sample reported that no one in their household knew of their HIV-positive status. Seventy percent of the sample earned over 4000 RMB per month, which is comparable to the national average (Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, Citation2015).

All participants completed 100% of the study sessions, showing up to all appointments and remaining for the duration of all study content; each participant also attempted the homework for each session, suggesting adherence to the intervention. Furthermore, during the knowledge check portion of the semi-structured exit interview, all participants reported accurate responses to the function of the intervention, and were able to summarize the three skills.

Psychological outcomes

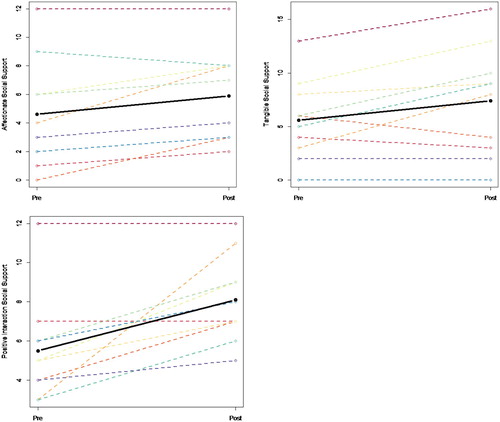

Paired samples t tests were conducted to compare nine mental health indicators at baseline and post intervention (See ). Participants reported significant reductions in PHQ-9 depression symptoms, t(9) = −2.62, p < .05 and BASE-7 problems in adjustment, t(9) = −2.40, p < .05. Participants also reported significant improvements in HIV coping skills, t(9) = 5.16, p < .001; total social support, t(9) = 3.31, p < .01; emotional/informational support, t(9) = 2.47, p < .05; affectionate support, t(9) = 2.9, p < .05; tangible support, t(9) = 2.29, p < .05; and positive social interaction, t(9) = 3.55, p < .01. Effect sizes for every comparison ranged from medium (0.5) to large (0.8) effects (Cohen, Citation1988). Detailed results are provided in . Individual trajectories of change on each outcome are plotted in .

Figure 1. Individual trajectories of participants.

Table 2. Dependent samples t tests of mental health indicators from baseline to post-intervention.

Feasibility and acceptability

Quantitative

The mean Client Satisfaction Questionnaire score was 66.5 (SD = 6.55) out of a possible maximum 76. On 4-point Likert-type items, the average rating for each item was 3.51, which corresponds to anchors between Somewhat/Generally and Very/Extremely Satisfied. On 6-point Likert-type items, the average rating for each item was 5.23, which corresponds to anchors between Agree and Strongly Agree to liking and being satisfied with the intervention.

The mean acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness score as measured by the AFAS was 44.3 (SD = 3.2) out of a possible maximum of 50, indicating an average rating for each item of 4.4 out of 5, landing between verbal anchors of 3-Moderately (3) and 5-Extremely acceptable, feasible, and appropriate.

The mean Acceptability of Intervention score was 62.9 (SD = 6.28) out of a possible 72, indicating an average rating for each item of 5.24, between Agree and Strongly Agree for acceptability.

The mean score on the Treatment Acceptability Questionnaire single item was 6.20 (SD = .63) out of a possible 7 (Very Acceptable) for the intervention overall.

Qualitative

Participant responses fell into broad themes of 1) positive responses to the Psychology Toolbox intervention; 2) perceived changes as a result of the intervention; and 3) suggestions for future implementation.

Theme 1: positive responses to the psychology toolbox intervention

All participants reported that they found the intervention helpful and that they learned useful skills as a result of it.

I learned a lot of new things – these skills allow me not to be as agitated as I was before when I face new problems; I have not completely acquired them fluently but I will use them in the future … It was so helpful that I recommended it to my boyfriend. – Male, 25 years old

Theme 2: perceived changes as a result of the program

Participants articulated changes they observed in their daily living as a result of going through the intervention.

The Automatic Thought Record was the most helpful for me – now I don't think about the worst-case scenario only, I think about every possibility … At the moment, I have some but not very obvious and big improvements, but I think I will continue to use it in the future, and if my situation gets worse, it will be even more helpful. –Male, 25 years old

Theme 3: suggestions for future implementation

The participants overwhelmingly indicated appreciation of the interventionist’s role as a non-hospital doctor or nurse, suggesting that her position facilitated non-judgmentalness and non-directive interaction, which is not typical of existing doctor/nurse and patient relationships. They highlighted this as a critical component in their acceptance of the intervention.

I feel you support me, give me your examples, and are authentic and equal. It helps me feel more secure. If it’s a nurse or someone else in the hospital, no matter how nice they are, there is a power differential. They think about healing illness not about mental health thoughts. Also, doctors and nurses have more professional concerns so their suggestions will be cooler and not as warm. – Male, 24 years old

The Community Advisory Board (CAB) consulted regarding implementation of the intervention echoed participants’ positive responses to the intervention, in particular that topics were useful and timing was opportune. CAB members highlighted several difficulties: that implementation would require staff who are already engaged in a full-time case load (whether nursing, physicians, the case worker) and would need to be taking on additional responsibilities to deliver an intervention. For a sustainable future model, the CAB highlighted the importance of either finding additional staff or re-distribution of responsibility for particular nurses/case workers to fulfill this role.

Discussion

This is the first known study examining a behavioral intervention to reduce HIV-related distress and improve coping and resilience among recently diagnosed MSM in China. The pilot trial yielded promising results. Although the sample size was small and not powered for efficacy, differences were detected in hypothesized directions for depression, adjustment problems, coping skills, total social support, tangible support, affectionate support, emotional/informational support, and positive social interaction due to large effect sizes.

As previous studies have been conducted employing mixed methods to examine implementation (e.g., Palinkas et al., Citation2011), upon completion of the intervention and post-intervention assessment, participants filled out additional measures of treatment acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility. Qualitative exit interviews were also conducted with participants to understand their perspectives on the implementation of the intervention. Overall, participants responded positively to the intervention both qualitatively and quantitatively, indicating that it was helpful, acceptable, and appropriate.

There are several limitations to this study. Due to limited resources, a preliminary study was conducted without a control sample, therefore analyzed differences between pre and post intervention. Future research may take advantage of experimental design including a control sample receiving treatment as usual to ensure that differences do not arise simply due to assessment. Another limitation is that the sample size was small and a convenience sample, suggesting that generalizability may be limited. Therefore, while improvements in mental health were consistently observed across all 10 participants, further exploration with a larger and more representative sample is warranted. It is likely qualitative interviews on implementation did not reach data saturation due to small sample size. Additionally, follow-up data were not collected from participants in the pilot trial. Longer term follow up post intervention may be warranted in future research to examine whether participants’ improvements are sustained.

Despite these limitations, this pilot trial shows promising results for the Psychology Toolbox intervention. Future implementation and dissemination research is warranted to explore factors of scaling the intervention up and training local interventionists (Simoni et al., Citation2015) to deliver the intervention. In addition, due to resource constraints, this pilot trial was focused on MSM due to their increased risk for psychological distress. Although preliminarily tested in MSM, it may be helpful for other recently HIV-diagnosed individuals, including men who have sex with women, or women. The constructs primarily targeted distress such as worry, fear, sadness, and isolation common to receiving an HIV diagnosis, therefore may be broadly applied to recently diagnosed individuals with a range of demographics. Future research may explore efficacy and effectiveness in a larger sample of recently diagnosed PLWHA.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our participants, as well as Ted Westling, Hu Mi, Tianyi Xie, and Leah Lucid for their support and help with this project. Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute of Mental Health under award number F31MH099925. Additional support was provided by the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) under award number AI027757 and the University of Washington Department of Psychology.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Joyce P. Yang http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6387-0594

Shannon Dorsey http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6240-0294

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aarons, G. A., Fettes, D. L., Sommerfeld, D. H., & Palinkas, L. (2012). Mixed methods for implementation research: Application to evidence-based practice implementation and staff turnover in community based organizations providing child welfare services. Child Maltreatment, 17(1), 67–79. doi: 10.1177/1077559511426908

- Attkisson, C. C., & Zwick, R. (1982). The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning, 5(3), 233–237. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-X

- Berg, B. L. (2004). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Betancourt, T. S., Meyers-Ohki, S. E., Charrow, A., & Hansen, N. (2013). Mental health and resilience in HIV/AIDS-affected children: A review of the literature and recommendations for future research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(4), 423–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02613.x

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-Translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301

- China AIDS Media Partnership, & UNAIDS. (2008). AIDS-Related knowledge, attitudes, behavior, and practices: A survey of 6 Chinese cities. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org.cn/uploadfiles/20081118143056.pdf

- Choi, K.-H., Gibson, D. R., Han, L., & Guo, Y. (2004). High levels of unprotected sex with men and women among men who have sex with men: A potential bridge of HIV transmission in Beijing, China. AIDS Education and Prevention, 16(1), 19–30. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.1.19.27721

- Choi, K. H., Liu, H., Guo, Y. Q., Han, L., Mandel, J. S., & Rutherford, G. W. (2003). Emerging HIV-1 epidemic in China in men who have sex with men. The Lancet, 361(9375), 2125–2126. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13690-2

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum.

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555

- Curran, G. M., Bauer, M., Mittman, B., Pyne, J. M., & Stetler, C. (2012). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care, 50(3), 217–226. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812

- Dittmann, I., & Jensen, T. K. (2014). Giving a voice to traumatized youth—experiences with trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(7), 1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.008

- Feng, Y., Wu, Z., & Detels, R. (2010). Evolution of MSM community and experienced stigma among MSM in chengdu, China. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 53(Suppl 1), S98–S103. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c7df71

- Gopalan, G. (2016). Feasibility of improving child behavioral health using task-shifting to implement the 4Rs and 2Ss program for strengthening families in child welfare. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 2, 21. doi:10.1186/s40814-016-0062-2

- Henninger, K. (2010). Exploring the relationship between factors of implementation, treatment integrity and reading fluency. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts–Amherst.

- Hunsley, J. (1992). Development of the treatment acceptability questionnaire. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 14(1), 55–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00960091

- Kaufman, J., & Jing, J. (2002). China and AIDS—The time to act is now. Science, 296(5577), 2339–2340. doi: 10.1126/science.1074479

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Lakens, D. (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 863. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863

- Li, X., Lu, H., Ma, X., Sun, Y., He, X., Li, C., … Jia, Y. (2012). HIV/AIDS-Related stigmatizing and discriminatory attitudes and recent HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Beijing. AIDS and Behavior, 16(3), 499–507. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0161-x

- Luthar, S. (1993). Annotation: Methodological and conceptual issues in research on childhood resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34(4), 441–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01030.x

- Lyon, A. R. (2012). Acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness scale (AFAS). Unpublished measure.

- Ma, X., Zhang, Q., He, X., Sun, W., Yue, H., Chen, S., … McFarland, W. (2007). Trends in prevalence of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. Results of 3 consecutive respondent-driven sampling surveys in Beijing, 2004 through 2006. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 45(5), 581–587. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31811eadbc

- Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. (2015). China Average Yearly Wages: 1952–2016. Retrieved from http://www.tradingeconomics.com/china/wages

- Murray, L. K., Skavenski, S., Michalopoulos, L. M., Bolton, P. A., Bass, J. K., Familiar, I., … Cohen, J. (2014). Counselor and client perspectives of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children in Zambia: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43(6), 902–914. doi:10.1080/15374416.2013.8 59079 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.859079

- Niu, L., Luo, D., Liu, Y., Silenzio, V. M. B., & Xiao, S. (2016). The mental health of people living with HIV in China, 1998–2014: A systematic review. PLOS ONE, 11(4), e0153489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153489

- Palinkas, L. A., Aarons, G. A., Horwitz, S., Chamberlain, P., Hurlburt, M., & Landsverk, J. (2011). Mixed method designs in implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 44–53. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z

- Peterson, A. P., Gordon, H. M., Cruz, R. A., Fagan, C., & Smith, R. E. (under review). Initial psychometric evaluation of the brief adjustment scale (BASE-6): A new measure of general psychological adjustment. Assessment.

- Phillips, M. R., Zhang, J., Shi, Q., Song, Z., Ding, Z., Pang, S., … Wang, Z. (2009). Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001-05: An epidemiological survey. The Lancet, 373(9680), 2041–2053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60660-7

- Powell, B. J., McMillen, J. C., Proctor, E. K., Carpenter, C. R., Griffey, R. T., Bunger, A. C., … York, J. L. (2012). A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Medical Care Research and Review, 69(2), 123–157. doi: 10.1177/1077558711430690

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., … Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

- Qian, Z. H., Vermund, S. H., & Wang, N. (2005). Risk of HIV/AIDS in China: Subpopulations of special importance. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 81(6), 442–447. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.014258

- Sherbourne, C. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine, 32(6), 705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B

- Simoni, J. M., Yang, J. P., Shiu, C.-S., Chen, W.-T., Udell, W., Bao, M., & Lu, H. (2015). Nurse-delivered counselling intervention for parental HIV disclosure: Results from a pilot randomized controlled trial in China. AIDS, 29(Suppl 1), S99–S107. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000664

- Thompson, R. J., Mata, J., Jaeggi, S. M., Buschkuehl, M., Jonides, J., … Gotlib, I. H. (2010). Maladaptive coping, adaptive coping, and depressive symptoms: Variations across age and depressive state. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(6), 459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.01.007

- UNAIDS. (2015). 2015 China AIDS response progress report. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/CHN_narrative_report_2015.pdf

- United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2010). Occupational outlook handbook: Psychology. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/ooh/Life-Physical-and-Social-Science/Psychologists.htm

- WHO. (2015). WHO | Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

- Wong, F. Y., Huang, Z. J., Wang, W., He, N., Marzzurco, J., Frangos, S., … Smith, B. D. (2009). STIs and HIV among men having sex with men in China: A ticking time bomb? AIDS Education and Prevention, 21(5), 430–446. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5.430

- World Health Organization. (2005). Mental health atlas 2005. Geneva: Author.

- Yang, J. P., Leu, J., Simoni, J. M., Chen, W. T., Shiu, C.-S., & Zhao, H. (2015). “Please don’t make me ask for help”: implicit social support and mental health in Chinese individuals living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 19(8), 1501–1509. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1041-y

- Yang, J. P., Simoni, J., Cheryan, S., Shiu, C., Chen, W., Zhao, H., & Lu, H. (2018). The development of a brief distress reduction intervention for individuals recently diagnosed with HIV in China. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 25(2), 319–334. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2017.08.002

- Yeung, A., Fung, F., Yu, S.-C., Vorono, S., Ly, M., Wu, S., & Fava, M. (2008). Validation of the patient health questionnaire-9 for depression screening Among Chinese Americans. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(2), 211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.06.002

- Yu, D. S. F., Lee, D. T. F., & Woo, J. (2004). Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS-C). Research in Nursing & Health, 27(2), 135–143. doi: 10.1002/nur.20008

- Yu, Y., Yang, J. P., Shiu, C.-S., Simoni, J. M., Xiao, S., Chen, W.-T., … Wang, M. (2015). Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the medical outcomes study social support survey among people living with HIV/AIDS in China. Applied Nursing Research, 28(4), 328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.03.006

- Zhang, B. C., & Chu, Q. S. (2005). MSM and HIV/AIDS in China. Cell Research, 15(11), 858–864. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290359