ABSTRACT

Resilience literature has suggested the context-specific nature of resilience while such framework has yet to be expanded to health psychology research among HIV serodiscordant couples. Conceptualizing a couple affected by chronic diseases using a “we-ness” framework rather than two separate individuals is important for stress coping of the couple. Considering this social-cognitive context of couple coping would be helpful to facilitate resilience of both the patient and the spouse. It is not clear whether couple identity serves as a protective factor for HIV serodiscordant couples and whether stigma, a prevalent contextual risk in this population, will alter the strength of such a protective effect on well-being. This longitudinal study examined the protective effect of couple identity in predicting the psychological and physical well-being of HIV discordant couples and the moderating role of stigma in such associations. A total of 160 Chinese HIV serodiscordant couples completed the baseline survey and follow-up one year later. Results showed that couple identity predicted fewer depressive symptoms at both the within- and between-couple level and better self-rated physical health at the between-couple level one year later. These protective effects were diminished when HIV stigma was high. This study highlights the importance of examining resources with consideration of contextual factors. It also calls for the sensitivity of stigma in developing a couple-based intervention for HIV serodiscordant couples.

Introduction

With the development of antiretroviral therapy, HIV has become a chronic disease instead of a terminal disease (Deeks, Lewin, & Havlir, Citation2013). People living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and their informal caregivers (especially their spouses) still face enormous stress including stigma (Mak, Poon, Pun, & Cheung, Citation2007; Yu, Chan, & Zhang, Citation2016). Such stress has exposed them to the risk of health or mental health problems, including depression (Collins, Holman, Freeman, & Patel, Citation2006; Wight, Citation2000; Yu, Zhang, & Chan, Citation2016). Thus, it is important to investigate the resilience process to effective adjustment despite adversities in PLWHA and caregiving spouses.

Resilience, depicting the process of overcoming disadvantages and achieving positive adjustment, is context-specific (Fergus & Zimmerman, Citation2005; Wright, Masten, & Narayan, Citation2013). First, resources are contingent with the context as they root in ecological systems of the focal individual (Yates & Masten, Citation2004). For example, the belief of fate control, generated from traditional Chinese philosophy, was found beneficial for the resilience of Chinese PLWHA in our previous study (Yu, Zhang, Chow, Chan, & Chan, Citation2016). Moreover, instead of being universally beneficial, resources may interact with contextual factors and lead to various outcomes (Cauce, Stewart, Rodriquez, Cochran, & Ginzler, Citation2003; Masten, Citation2007). For instance, the effect of health literacy, a well-documented protective factor for physical health, was compromised when individuals had strong optimism biases about health (Ahn, Park, & Haley, Citation2014). Thus, resilience research among HIV serodiscordant couples should take into account context-specific resources and risks.

Couple identity may serve as a contextual protective factor for HIV serodiscordant couples because the sense of “we-ness” of the couple is both the social-cognitive context and a resource for couple coping with chronic diseases (Badr, Acitelli, & Carmack Taylor, Citation2007). Couple identity represents the identity transformation from self-orientation to couple-orientation for those who are in an intimate relationship (Surra & Bartell, Citation2001). With commitment and intimacy developing in couple relationships, members of the couple acquire a sense of we-ness that allows them to understand themselves as part of a couple rather than as independent individuals (Badr et al., Citation2007; Fincham, Stanley, & Beach, Citation2007). A strong couple identity may motivate partners to engage in relationship maintaining and mutual support activities (Badr & Acitelli, Citation2017; Helgeson, Jakubiak, Van Vleet, & Zajdel, Citation2018), thereby improving the couple’s well-being under the stress of chronic diseases. Couple identity has been reported to contribute to resilient outcomes in both mental and physical well-being among patients and caregiving spouses affected by various chronic diseases (e.g., cancer, diabetes; Badr et al., Citation2016; Kayser, Watson, & Andrade, Citation2007; Zajdel, Helgeson, Seltman, Korytkowski, & Hausmann, Citation2018). With the recent interest in dyadic studies among couples affected by HIV, emerging evidence has demonstrated how HIV discordant couples worked together to cope with HIV-related stress (Persson, Citation2008; Rispel, Cloete, Metcalf, Moody, & Caswell, Citation2012; Yu, Chan, & Zhang, Citation2016). However, the influence of couple identity on the resilience of the couples has not been clarified in empirical investigations.

HIV stigma is a significant contextual risk factor for HIV serodiscordant couples which should be considered in resilience research. Previous evidence has indicated that stigmatization of HIV has brought enormous pressure to PLWHA (Liamputtong, Citation2013). Seronegative spouses of PLWHA suffered from courtesy stigma (Goffman, Citation1963) including avoidance and accusation (Ho & Mak, Citation2013; Siegel, Meunier, & Lekas, Citation2018) because the public tended to treat the stigmatized individuals and people related to them “as one” (Goffman, Citation1963). Both PLWHA and spouses reported consequences of stigma in their psychological and physical well-being (e.g., depression, poor physical health; Charles et al., Citation2012; Earnshaw, Smith, Chaudoir, Amico, & Copenhaver, Citation2013; Wight, Citation2000; Yu, Zhang, & Chan, Citation2016). Despite consistent evidence in maladaptive outcomes of stigma, mixed findings have been reported regarding the interaction between HIV-related stigma and protective factors on the well-being of PLWHA or caregiving spouses. For instance, some reported that stigma weakened the benefits of coping resources on well-being (Chaudoir et al., Citation2012; Earnshaw, Lang, Lippitt, Jin, & Chaudoir, Citation2015), whereas others found no significant moderating effect of stigma (Breet, Kagee, & Seedat, Citation2014; Logie, James, Tharao, & Loutfy, Citation2013). With few exceptions including ours (e.g., Yu, Citation2017), most stigma studies have investigated PLWHA or caregivers in separate samples rather than considering HIV discordant couples as a whole suffering from stigma.

As important contextual protective and risk factors, respectively, couple identity and HIV stigma may interact in the resilience process of HIV serodiscordant couples. Specifically, the protective effect of couple identity on the well-being may be suppressed by stigma experience because stigma devaluated the self-identity and humanity of the stigmatized individual (Crocker, Major, & Steele, Citation1998). A strong couple identity bound the two partners and thereby expanded such devaluation of a partner to the devaluation of the couple (Zang, Guida, Sun, & Liu, Citation2014). Thus, PLWHA is particularly distressful about bringing disgrace to the couple, and the seronegative spouses feel devalued because “we have HIV”, even if they are not infected. Previous qualitative studies showed that such process brought additional shame, guilt and isolation to discordant couples, exacerbating the negative consequences of stigma (Li et al., Citation2008; Siegel et al., Citation2018). We-ness entailed in couple identity may further facilitate the transmission of distress within the couple (Larson & Almeida, Citation1999). As the stigma experience became overwhelming, soothing and coping competence brought by the we-ness were compromised, thereby creating emotional distress and undermining physical health (Earnshaw et al., Citation2013; Yu et al., Citation2009).

In sum, the context-specific nature of resilience suggests that the resilience process of PLWHA and caregiving spouses need to consider contextual protective and risk factors as well as the dynamics that they take effects (Fergus & Zimmerman, Citation2005; Masten, Citation2007). It is not clear whether couple identity, the social-cognitive context of couples coping with HIV, could work as a protective factor for HIV serodiscordant couples. Moreover, as a prevalent contextual risk factor of HIV discordant couples, the potential moderating effect of stigma needs investigation. Using a sample of Chinese HIV discordant couples, the present study with a longitudinal design investigated the effect of couple identity on the psychological and physical well-being and the moderating role of stigma at the levels of both within and across couples. We hypothesized that (1) within the HIV serodiscordant couple, the member with stronger couple identity would have fewer depressive symptoms one year later (couple identity may not predict better self-rated physical health at the individual level because HIV serostatus leads to discrepant ratings of physical health between the patient and spouse); (2) across HIV serodiscordant couples, couples with a stronger couple identity would have lower levels of depressive symptoms and better self-rated physical health one year later; and (3) stigma will diminish the protective effect of couple identity on both psychological and physical well-being, within and across couples, respectively.

Materials and methods

Study design

Physical and psychological well-being of HIV serodiscordant couples may demonstrate contingent changes over time under the persistent and interacting influences of couple identity and stigma as contextual protective and risk factors, respectively (Miller & Blackwell, Citation2006; Pearlin, Aneshensel, & Leblanc, Citation1997). Therefore, we adopted the two-wave longitudinal design and examined the predictive value of couple identity and its interaction with stigma on well-being outcomes one year later. The baseline survey of this study was conducted from July to November 2015 (Time 1, T1) and the follow-up was conducted one year later (Time 2, T2). Both patients and their HIV discordant spouses completed all of these measures.

Participants

The present study was conducted in five villages randomly selected from villages with HIV prevalence greater than 10% in Henan province, China. A large number of people there were infected with HIV via a commercial blood donation (Wu, Liu, & Detels, Citation1995). A total of 160 HIV serodiscordant couples were recruited to participate in this study. The inclusion criteria were (1) one member of the couple was infected with HIV while the other was not, and (2) being married for more than five years. Only two couples failed to follow up with the survey at T2, which made our valid sample 158 couples.

Procedure

Due to the low education levels of the participants, trained local health service providers conducted structural interviews face to face (separately with each member of the couple). The participants provided informed consents to participate and received compensation for their time spent on the survey (CNY60 for each participant, approximately equivalent to USD10). Ethical approval was obtained from the City University of Hong Kong.

Measures

We measured the participants’ demographic information (including gender, age, education, duration of marriage, annual family income) and the duration of diagnosis of HIV. We adhered to the original designs of the questionnaires so that the rating scale values were not consistent in the study measures. Such practice is helpful to decrease the possibility of common method biases (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003).

Couple identity was measured with two items that Acitelli, Rogers, and Knee (Citation1999) developed. Items were translated into Chinese following the translation-back translation procedure. Participants indicated the extent to which they view themselves as “being part of a couple” and how important “being part of a couple” is to their self-view on a five-Likert scale. This measure of couple identity showed good internal consistency at T1 (α = 0.91, average of the couple).

Stigma was measured using a nine-item measure that Wight and colleagues (Citation2006) developed. This measure was designed to assess the stigma experience of shame, rejection, and avoidance (e.g., “feel people avoid you”) in response to the patient’s HIV infection as being the patient himself/herself or as being the caregiving spouse. Participants rated each item on a four-point Likert scale. The English version went through the translation-back translation procedure to produce the Chinese version. The average internal consistency of patients and spouses at T1 was 0.84.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke & Spitzer, Citation2002). Based on the diagnosis criteria of the depressive disorder of DSM-IV, the PHQ-9 was developed to assess the severity of depression (e.g., “Little interest or pleasure in doing things”). Participants rated the items based on their feelings in the past two weeks on a four-point Likert scale. The Chinese version of the PHQ-9 was validated and showed good psychometric properties (Yu, Tam, Wong, Lam, & Stewart, Citation2012). The internal consistency values in the present study for the average of the couples at T1 and T2 were 0.93 and 0.92, respectively.

Self-rated physical health was measured using eight items from the brief version of the WHO Quality of Life instrument (WHOQLO-BREF). One item assesses general health satisfaction (“How satisfied are you with your health?”), and the other seven cover more detailed physical functions (e.g., “To what extent do you feel that physical pain prevents you from doing what you need to do?”). The Chinese version was validated with good psychometric properties (Leung, Wong, Tay, Chu, & Ng, Citation2005). Participants indicated their responses on a five-point Likert scale. This measure demonstrated good internal consistency at T1 (α = 0.89) and T2 (α = 0.88) as the average of the couples.

Data analysis

Due to the multilevel nature of data in the present study (Level 1 = individual, Level 2 = couple), we used Multilevel Modeling to test our hypotheses, a method which addresses the interdependence of both levels and specifies separate models for each level (Muthen & Satorra, Citation1995). Covariates including T1 dependent variables, demographic characteristics, HIV characteristics and HIV serostatus of participants were controlled in the analyses. Assessments of moderation and subsequent simple slope tests were conducted following previous recommendations of practices in the multilevel analysis (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, Citation2006; Preacher, Zhang, & Zyphur, Citation2016). The multilevel analyses were conducted with Mplus 7.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in . Most of the participants were middle aged (patients: 50.15 ± 7.49; spouses: 50.15 ± 7.49) with relatively long-term marriages (26.28 ± 7.00).

Table 1. Demographic and HIV-related characteristics of patients and spouses.

shows descriptive statistics of the studied variables and correlations at the couple level. Couple identity measured at T1 was significantly associated with depressive symptoms at T1 and T2, and self-rated physical health at T2, except for self-rated physical health at T1.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of the study variables at the couple level.

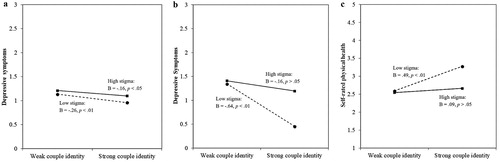

presents the results of Multilevel Modeling. Covariates were included in the analyses but omitted from the table due to space limit. To test Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2, couple identity was added to predict depressive symptoms in Model A and to predict self-rated physical health in Model C. At the within-couple level, couple identity significantly predicted fewer depressive symptoms but not self-rated physical health, which supports Hypothesis 1. At the between-couple level, couple identity significantly predicted fewer depressive symptoms and marginally significantly predicted better self-rated physical health, which supports Hypothesis 2. To test Hypothesis 3, couple identity, stigma, and the interaction term between them were added to predict depressive symptoms in Model B and to predict self-rated physical health in Model D. Results showed that the interaction term of stigma and couple identity significantly predicted depressive symptoms at both the within- and between-couple level, and significantly predicted self-rated physical health at the between-couple level. These results support Hypothesis 3, suggesting the moderating role of stigma in the association between-couple identity and depressive symptoms both within and across couples, and in the association between-couple identity and self-rated physical health across couples. We plotted interactions and conducted simple slope tests for Model A, B, and D.

Table 3. Multilevel estimates for depressive symptoms and self-rated physical health.

As shown in (a), within the HIV serodiscordant couple, depressive symptoms at T2 were attenuated as a function of couple identity when the individual experienced a low level of stigma. Such a protective effect was less strong when stigma experience was higher. (b,c) present the between-level interactions, showing that stronger couple identity of the couple significantly predicted fewer depressive symptoms and better self-rated physical health if the couple had a lower level of stigma experience; however, depressive symptoms and self-rated physical health were not significantly predicted by couple identity when the couple reported a higher level of stigma.

Discussion

Addressing on the context-specific nature of resilience (Fergus & Zimmerman, Citation2005; Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, Citation2000; Masten, Citation2007), this study examined the mechanism that contextual protective and risk factors impact the well-being of HIV serodiscordant couples. Using a longitudinal design with a dyadic approach, this study demonstrated the effects of couple identity on well-being outcomes and the moderating roles of stigma at levels of both within and across couples. Our findings demonstrated that HIV serodiscordant couples with stronger couple identity showed fewer depressive symptoms and better self-rated physical health one year later, and these protective effects were attenuated by stigma experience of the couples. When looking within the couple, the member who had a higher level of couple identity was less likely to be depressed, and the protective effect of couple identity was suppressed if one experienced strong stigma. This study provides evidence for social-cognitive notion that the method of conceptualizing relationship can have an impact on dyadic stress adjustment (Badr et al., Citation2007). It also expands such theoretical model to the HIV context by taking stigma into consideration. Our results highlight the importance of validating the role of resources with considering relevant contextual factors of specific at-risk populations.

The results of this study demonstrate the role of couple identity as a resource for Chinese HIV serodiscordant couples with HIV transmitted via commercial blood donation. It is in line with previous findings that supported the protective role of we-ness in other groups of HIV serodiscordant couples (e.g., heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples, homosexual HIV serodiscordant couples; Gamarel, Comfort, Wood, Neilands, & Johnson, Citation2016; Montgomery, Watts, & Pool, Citation2012; Wrubel, Stumbo, & Johnson, Citation2010). For example, Pomeroy and colleagues (Citation2002) found that an intervention entailing the component of we-oriented coping with HIV improved the mental health of American heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples. Our findings on the benefits of couple identity are also consistent with evidence in discordant couples living with other chronic diseases such as diabetes and cancer in other cultures that we-ness improved couple adjustment to illnesses (Badr et al., Citation2016; Helgeson, Jakubiak, Seltman, Hausmann, & Korytkowski, Citation2017; Zajdel et al., Citation2018). However, the contextual risk factor of stigma is not experienced by couples affected by chronic diseases such as cancer and heart diseases, highlighting the unique nature of HIV research. In line with previous studies that were dominantly conducted in Western cultures (Badr et al., Citation2016; Helgeson et al., Citation2017; Zajdel et al., Citation2018), our findings in Chinese HIV serodiscordant couples also demonstrate the protective role of couple identity. Moreover, the present study provides quantitative and longitudinal support for the long-existing clinical strategy of fostering couple identity to improve couple adjustment (Heinrichs et al., Citation2012; Montgomery et al., Citation2012; Reid, Dalton, Laderoute, Doell, & Nguyen, Citation2006) in the HIV context. It also has strong implications for promoting we-ness as a supplement for major therapeutic components of resilience interventions (e.g., emotion management, problem solving) in coping with HIV-related stress among these discordant couples. The underlying mechanism and process of how couple identity facilitates the resilience process in HIV discordant couples remain unclear. Three explanations exist to account for the protective role of couple identity. First, caregiver burden and care-receiver’s guilt may be relieved when both partners conceptualize themselves as being inseparable from each other (Badr et al., Citation2007). Second, increased cooperation in family life (e.g., household duties reassigning), as a result of strong couple identity (Garrido & Acitelli, Citation1999), may alleviate the disturbance created by diseases (Helgeson, Citation1993; Hodgson, Garcia, & Tyndall, Citation2004), thereby improving couples’ adjustment. Third, the mutuality of engaging both partners in shared activities entailed in couple identity can draw the couple together to cope with the disease even at the cost of sacrificing personal boundaries and freedom (Jordan, Citation1997; Kayser et al., Citation2007).

The contributive role of couple identity in resilience deserves further validation across social-economic and generational contexts. First, as mutual reliance is pivotal for couples with poor economic statuses and limited access to health care service (Walsh, Citation2015), couple identity may be particularly important in this population. Future studies can consider validating the effects of couple identity in couples with more health service resources. Second, despite substantial evolutions in marriage and family (e.g., declined marriage rates, increased marriage age, low fertility rate, rising divorce rate) in Eastern Asian societies in the past few decades (Ji, Citation2015), marital values of the younger generations had remained relatively conventional (e.g., considering marriage as a must; Kim & Cheung, Citation2015; Yeung & Hu, Citation2016). It is possible that couple identity remains significant and still serves as a resource in younger generations of Eastern cultures, and future studies are warranted to replicate our findings.

As expected, our findings suggest that stigma suppressed the protective effect of couple identity on both the psychological and physical well-being in HIV serodiscordant couples with HIV transmitted via commercial blood donation. To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the interaction between couples’ we-ness and stigma experience in HIV serodiscordant couples. Our findings are consistent with the experience of PLWHA and seronegative spouses reported in previous qualitative studies (Rispel, Cloete, & Metcalf, Citation2015; Siegel et al., Citation2018). For instance, a concern of bringing stigma to spouses led to enormous distress and even suicidal attempts in PLWHA who were injection drug users (Salter et al., Citation2010). These findings support the context-specific nature of resilience (Fergus & Zimmerman, Citation2005), demonstrating the interaction between contextual resources and risks in the resilience process of HIV discordant couples. It is consistent with previous findings that the same protective factors such as optimism and parental monitoring could lead to different outcomes in face of different contextual risks (Crosnoe, Erickson, & Dornbusch, Citation2002; Gutman, Sameroff, & Eccles, Citation2002; Wright et al., Citation2013). Instead of being treated as universally protective, resources should be validated with related contextual factors of the specific at-risk population. Unlike most previous studies that focused only on the stigma experience of patients or caregiving spouses, we addressed on the relational context of HIV serodiscordant couples, including both members to better depict the dynamics of impacts of stigma in HIV serodiscordant couples. This study provides extending evidence that the consequence of stigma may be transmitted and exacerbated within the couple via couple identity. As for clinical consideration, this study also highlights the importance of considering contextual factors in resilience interventions. For example, service providers are advised to be sensitive to the contextual HIV stigma against both patients and spouses and take into account such negative experiences in intervention strategies. In support of such implication, previous evidence has suggested that family intervention programs addressing stigma issues showed good efficacy (Hoffman et al., Citation2005; Sanders, Citation1999). In addition, as the stigma is widespread in various diseases, such as dementia and physical disability (Goldstein & Johnson, Citation1997; Liu, Hinton, Tran, Hinton, & Barker, Citation2008), the interaction between stigma and resources merits replications in the context of other stigmatized diseases.

The current study featured some limitations. First, due to the difficulty of recruiting both PLWHA and their serodiscordant spouses, we managed to recruit only 158 couples to participate in this study. The relatively small sample size may undermine the reliability and robustness of the results given that previous studies on patient-caregiver dyads affected by HIV involved caregivers, combining the spouses, parents, and siblings of patients (e.g., Casale & Wild, Citation2013; Mitchell & Knowlton, Citation2009; Wight, Aneshensel, Murphy, Miller-Martinez, & Beals, Citation2006). Our study provides new evidence on how patient-spouse dyads cope with HIV and related stress. Second, unlike most PLWHA, the sample of this study was infected during the process of commercial blood donation, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to PLWHA who were infected via injection drug use or sexual behaviors. Third, this study used structural interviews instead of a self-administered survey due to the low education levels of the participants. However, although all interviewers were trained, this may have led to risks of social desirability or the reluctance of disclosure, especially when the survey involved sensitive issues, such as stigma. Fourth, this study had difficulty to collect HIV-related health information of PLWHA (e.g., CD4, virus load) as outcomes because of the limited health service accessibility and the lack of regular tests in our sample.

Despite limitations, the present study provides new knowledge regarding the resilience process in HIV discordant couples, by addressing on their social-cognitive context of couple interdependence in face of stigma. With a longitudinal design, this study identified the role of couple identity as a resource for HIV serodiscordant couples. It also found that such protective effect was compromised by a high level of stigma experience. Expanding the dyadic approach to HIV serodiscordant couples, this study contributes to knowledge about how spouses’ understanding of the couple as a whole interacts with contextual stigma experience in the resilience process. These findings support fostering couple identity as a clinical strategy for improving the well-being of couples affected by chronic diseases. They also call for actions against consequences of stigma in both members of HIV serodiscordant couples.

Acknowledgments

The sponsor had no further role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Nancy Xiaonan Yu http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6371-2684

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acitelli, L. K., Rogers, S., & Knee, C. R. (1999). The role of identity in the link between relationship thinking and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 16, 591–618. doi: 10.1177/0265407599165003

- Ahn, H. Y., Park, J. S., & Haley, E. (2014). Consumers’ optimism bias and responses to risk disclosures in direct-to-consumer (DTC) prescription drug advertising: The moderating role of subjective health literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 48, 175–194. doi: 10.1111/joca.12028

- Badr, H., & Acitelli, L. K. (2017). Re-thinking dyadic coping in the context of chronic illness. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.001

- Badr, H., Acitelli, L. K., & Carmack Taylor, C. L. (2007). Does couple identity mediate the stress experienced by caregiving spouses? Psychology and Health, 22, 211–229. doi: 10.1080/14768320600843077

- Badr, H., Milbury, K., Majeed, N., Carmack, C. L., Ahmad, Z., & Gritz, E. R. (2016). Natural language use and couples’ adjustment to head and neck cancer. Health Psychology, 35, 1069–1080. doi: 10.1037/hea0000377

- Breet, E., Kagee, A., & Seedat, S. (2014). HIV-related stigma and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in HIV-infected individuals: Does social support play a mediating or moderating role? AIDS Care, 26, 947–951. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.901486

- Casale, M., & Wild, L. (2013). Effects and processes linking social support to caregiver health among HIV/AIDS-affected carer-child dyads: A critical review of the empirical evidence. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 1591–1611. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0275-1

- Cauce, A. M., Stewart, A., Rodriquez, M. D., Cochran, B., & Ginzler, J. (2003). Overcoming the odds. In S. S. Luthar (Ed.), Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in The context of childhood adversities (pp. 343–363). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Charles, B., Jeyaseelan, L., Pandian, A. K., Sam, A. E., Thenmozhi, M., & Jayaseelan, V. (2012). Association between stigma, depression and quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) in south India: A community based cross sectional study. BMC Public Health, 12, 463–473. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-463

- Chaudoir, S. R., Norton, W. E., Earnshaw, V. A., Moneyham, L., Mugavero, M. J., & Hiers, K. M. (2012). Coping with HIV stigma: Do proactive coping and spiritual peace buffer the effect of stigma on depression? AIDS and Behavior, 16, 2382–2391. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0039-3

- Collins, P. Y., Holman, A. R., Freeman, M. C., & Patel, V. (2006). What is the relevance of mental health to HIV/AIDS care and treatment programs in developing countries? A systematic review. AIDS (London, England), 20, 1571–1582. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238402.70379.d4

- Crocker, J., Major, B., & Steele, C. (1998). Social stigma. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 504–553). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Crosnoe, R., Erickson, K. G., & Dornbusch, S. M. (2002). Protective functions of family relationships and school factors on the deviant behavior of adolescent boys and girls: Reducing the impact of risky friendships. Youth & Society, 33, 515–544. doi: 10.1177/0044118X02033004002

- Deeks, S. G., Lewin, S. R., & Havlir, D. V. (2013). The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. The Lancet, 382, 1525–1533. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61809-7

- Earnshaw, V. A., Lang, S. M., Lippitt, M., Jin, H., & Chaudoir, S. R. (2015). HIV stigma and physical health symptoms: Do social support, adaptive coping, and/or identity centrality act as resilience resources? AIDS and Behavior, 19, 41–49. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0758-3

- Earnshaw, V. A., Smith, L. R., Chaudoir, S. R., Amico, K. R., & Copenhaver, M. M. (2013). HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: A test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 1785–1795. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9

- Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357

- Fincham, F. D., Stanley, S. M., & Beach, S. R. (2007). Transformative processes in marriage: An analysis of emerging trends. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 275–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00362.x

- Gamarel, K. E., Comfort, M., Wood, T., Neilands, T. B., & Johnson, M. O. (2016). A qualitative analysis of male couples’ coping with HIV: Disentangling the “we.”. Journal of Health Psychology, 21, 2125–2137. doi: 10.1177/1359105315571975

- Garrido, E. F., & Acitelli, L. K. (1999). Relational identity and the division of household labor. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 16, 619–637. doi: 10.1177/0265407599165004

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Goldstein, S. B., & Johnson, V. A. (1997). Stigma by association: Perceptions of the dating partners of college students with physical disabilities. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 19, 495–504. doi: 10.1207/s15324834basp1904_6

- Gutman, L. M., Sameroff, A. J., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). The academic achievement of African American students during early adolescence: An examination of multiple risk, promotive, and protective factors. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 367–99. doi: 10.1023/A:1015389103911

- Heinrichs, N., Zimmermann, T., Huber, B., Herschbach, P., Russell, D. W., & Baucom, D. H. (2012). Cancer distress reduction with a couple-based skills training: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 43, 239–252. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9314-9

- Helgeson, V. S. (1993). The onset of chronic illness: Its effect on the patient-spouse relationship. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 12, 406–428. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1993.12.4.406

- Helgeson, V. S., Jakubiak, B., Seltman, H., Hausmann, L., & Korytkowski, M. (2017). Implicit and explicit communal coping in couples with recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34, 1099–1121. doi: 10.1177/0265407516669604

- Helgeson, V. S., Jakubiak, B., Van Vleet, M., & Zajdel, M. (2018). Communal coping and adjustment to chronic illness: Theory update and evidence. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22, 170–195. doi: 10.1177/1088868317735767

- Ho, C. Y., & Mak, W. W. (2013). HIV-related stigma across cultures: Adding family into the equation. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Stigma, discrimination and living with HIV/AIDS (pp. 53–69). London: Springer.

- Hodgson, J. H., Garcia, K., & Tyndall, L. (2004). Parkinson’s disease and the couple relationship: A qualitative analysis. Families, Systems & Health, 22, 101–119. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.22.1.101

- Hoffman, P. D., Fruzzetti, A. E., Buteau, E., Neiditch, E. R., Penney, D., Bruce, M. L., … Struening, E. (2005). Family connections: A program for relatives of persons with borderline personality disorder. Family Process, 44, 217–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00055.x

- Ji, Y. (2015). Asian families at the crossroads: A meeting of east, west, tradition, modernity, and gender. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 1031–1038. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12223

- Jordan, J. V. (1997). Women’s growth in diversity: More writings from The Stone Center. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Kayser, K., Watson, L. E., & Andrade, J. T. (2007). Cancer as a “we-disease”: examining the process of coping from a relational perspective. Families, Systems, & Health, 25, 404–418. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.25.4.404

- Kim, E. H. W., & Cheung, A. K. L. (2015). Women’s attitudes toward family formation and life stage transitions: A longitudinal study in Korea. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 1074–1090. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12222

- Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32, 509–515. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06

- Larson, R. W., & Almeida, D. M. (1999). Emotional transmission in the daily lives of families: A new paradigm for studying family process. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 5–20. doi: 10.2307/353879

- Leung, K., Wong, W., Tay, M., Chu, M., & Ng, S. (2005). Development and validation of the interview version of the Hong Kong Chinese WHOQOL-BREF. Quality of Life Research, 14, 1413–1419. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-4772-1

- Li, L., Wu, Z., Wu, S., Jia, M., Lieber, E., & Lu, Y. (2008). Impacts of HIV/AIDS stigma on family identity and interactions in China. Families, Systems, & Health, 26, 431–442. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.26.4.431

- Liamputtong, P. (2013). Stigma, discrimination, and HIV/AIDS: An introduction. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Stigma, discrimination and living with HIV/AIDS (pp. 53–69). London: Springer.

- Liu, D., Hinton, L., Tran, C., Hinton, D., & Barker, J. C. (2008). Reexamining the relationships among dementia, stigma, and aging in immigrant Chinese and Vietnamese family caregivers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 23, 283–299. doi: 10.1007/s10823-008-9075-5

- Logie, C., James, L., Tharao, W., & Loutfy, M. (2013). Associations between HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, gender discrimination, and depression among HIV-positive African, Caribbean, and Black women in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 27, 114–122. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0296

- Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71, 543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164

- Mak, W. W., Poon, C. Y., Pun, L. Y., & Cheung, S. F. (2007). Meta-analysis of stigma and mental health. Social Science & Medicine, 65, 245–261. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.015

- Masten, A. S. (2007). Resilience in developing systems: Progress and promise as the fourth wave rises. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 921–930. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000442

- Miller, G. E., & Blackwell, E. (2006). Turning up the heat: Inflammation as a mechanism linking chronic stress, depression, and heart disease. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 269–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00450.x

- Mitchell, M. M., & Knowlton, A. (2009). Stigma, disclosure, and depressive symptoms among informal caregivers of people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23, 611–617. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0279

- Montgomery, C. M., Watts, C., & Pool, R. (2012). HIV and dyadic intervention: An interdependence and communal coping analysis. PLOS ONE, 7: e40661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040661

- Muthen, B. O., & Satorra, A. (1995). Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociological Methodology, 25, 267–316. doi: 10.2307/271070

- Pearlin, L. I., Aneshensel, C. S., & Leblanc, A. J. (1997). The forms and mechanisms of stress proliferation: The case of AIDS caregivers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 223–236. doi: 10.2307/2955368

- Persson, A. (2008). Sero-silence and sero-sharing: Managing HIV in serodiscordant heterosexual relationships. AIDS Care, 20, 503–506. doi: 10.1080/09540120701787487

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Pomeroy, E. C., Green, D. L., & Van Laningham, L. (2002). Couples who care: The effectiveness of a psychoeducational group intervention for HIV serodiscordant couples. Research on Social Work Practice, 12, 238–252. doi: 10.1177/104973150201200203

- Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31, 437–448. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437

- Preacher, K. J., Zhang, Z., & Zyphur, M. J. (2016). Multilevel structural equation models for assessing moderation within and across levels of analysis. Psychological Methods, 21, 189–205. doi: 10.1037/met0000052

- Reid, D. W., Dalton, E. J., Laderoute, K., Doell, F. K., & Nguyen, T. (2006). Therapeutically induced changes in couple identity: The role of we-ness and interpersonal processing in relationship satisfaction. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 132, 241–284. doi: 10.3200/MONO.132.3.241-288

- Rispel, L. C., Cloete, A., & Metcalf, C. A. (2015). “We keep her status to ourselves”: Experiences of stigma and discrimination among HIV-discordant couples in South Africa, Tanzania and Ukraine. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 12, 10–17. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2015.1014403

- Rispel, L. C., Cloete, A., Metcalf, C. A., Moody, K., & Caswell, G. (2012). “It [HIV] is part of the relationship”: Exploring communication among HIV-serodiscordant couples in South Africa and Tanzania. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14, 257–268. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.621448

- Salter, M. L., Go, V. F., Minh, N. L., Gregowski, A., Ha, T. V., Rudolph, A., … Quan, V. M. (2010). Influence of perceived secondary stigma and family on the response to HIV infection among injection drug users in Vietnam. AIDS Education and Prevention, 22, 558–570. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.6.558

- Sanders, M. R. (1999). Triple P-positive parenting program: Towards an empirically validated multilevel parenting and family support strategy for the prevention of behavior and emotional problems in children. Clinical Child and Family Ppsychology Review, 2, 71–90. doi: 10.1023/A:1021843613840

- Siegel, K., Meunier, É, & Lekas, H. M. (2018). The experience and management of HIV stigma among HIV-negative adults in heterosexual serodiscordant relationships in New York City. AIDS Care, 30, 871–878. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1441971

- Surra, C., & Bartell, D. (2001). Attributions, communication, and the development of a marital identity. In V. Manusov & J. H. Harvey (Eds.), Attribution, communication behavior, and close relationships (pp. 93–114). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Walsh, F. (2015). Strengthening family resilience. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

- Wight, R. G. (2000). Precursive depression among HIV infected AIDS caregivers over time. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 759–770. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00007-1

- Wight, R. G., Aneshensel, C. S., Murphy, D. A., Miller-Martinez, D., & Beals, K. P. (2006). Perceived HIV stigma in AIDS caregiving dyads. Social Science & Medicine, 62, 444–456. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.004

- Wright, M. O., Masten, A. S., & Narayan, A. J. (2013). Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In S. Goldstein, & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 15–37). New York: Springer.

- Wrubel, J., Stumbo, S., & Johnson, M. O. (2010). Male same-sex couple dynamics and received social support for HIV medication adherence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27, 553–572. doi: 10.1177/0265407510364870

- Wu, Z., Liu, Z., & Detels, R. (1995). HIV-1 infection in commercial plasma donors in China. The Lancet, 346, 61–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92698-4

- Yates, T. M., & Masten, A. S. (2004). Fostering the future: Resilience theory and the practice of positive psychology. In P. A. Linley, & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 521–539). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Yeung, W. J. J., & Hu, S. (2016). Paradox in marriage values and behavior in contemporary China. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 2, 447–476. doi: 10.1177/2057150X16659019

- Yu, N. X. (2017). The effects of beliefs about AIDS-related death on quality of life in Chinese married couples with both husband and wife infected with HIV: Examining congruence using the actor-partner interdependence model. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15, 127–131. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0703-z

- Yu, N. X., Chan, C. L., & Zhang, J. (2016). Dyadic effects of stigma and discrimination on distress in Chinese HIV discordant couples. AIDS Education and Prevention, 28, 277–286. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2016.28.4.277

- Yu, N. X., Lau, J., Mak, W., Cheng, Y., Lv, Y., & Zhang, J. (2009). Risk and protective factors in association with mental health problems among people living with HIV who were former plasma/blood donors in rural China. AIDS Care, 21, 645–654. doi: 10.1080/09540120802459770

- Yu, N. X., Tam, W. W., Wong, P. T., Lam, T. H., & Stewart, S. M. (2012). The patient health questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms among the general population in Hong Kong. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53, 95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.11.002

- Yu, N. X., Zhang, J., & Chan, C. L. (2016). Health care neglect, perceived discrimination, and dignity-related distress among Chinese patients with HIV. AIDS Education and Prevention, 28, 90–102. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2016.28.1.90

- Yu, N. X., Zhang, J., Chow, A. Y., Chan, C. H., & Chan, C. L. (2016). Fate control and well-being in Chinese rural people living with HIV: Mediation effect of resilience. AIDS Care, 29, 86–90. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1198749

- Zajdel, M., Helgeson, V. S., Seltman, H. J., Korytkowski, M. T., & Hausmann, L. R. M. (2018). Daily communal coping in couples with type 2 diabetes: Links to mood and self-care. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52, 228–238. doi: 10.1093/abm/kax047

- Zang, C., Guida, J., Sun, Y., & Liu, H. (2014). Collectivism culture, HIV stigma and social network support in Anhui, China: A path analytic model. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 28, 452–458. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0015