ABSTRACT

Overlapping stigmas related to sexual minority-, race/ethnicity-, and HIV-status pose barriers to HIV prevention and care and the creation of supportive social networks for young, Black, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM). A risk-based approach to addressing the HIV epidemic focuses on what is lacking and reinforces negative stereotypes about already-marginalized populations. In contrast, a strengths-based approach builds on Black GBMSM’s existing strengths, recognizing the remarkable ways in which they are overcoming barriers to HIV prevention and care. HealthMpowerment (HMP) is an online, mobile phone optimized intervention that aimed to reduce condomless anal intercourse and foster community among young Black GBMSM (age 18–30). Applying a resilience framework, we analyzed 322 conversations contributed by 48 HMP participants (22/48 living with HIV) on the intervention website. These conversations provided a unique opportunity to observe and analyze dynamic, interpersonal resilience processes shared in response to stigma, discrimination, and life challenges experienced by young Black GBMSM. We utilized an existing framework with four resilience processes and identified new subthemes that were displayed in these online interactions: (1) Exchanging social support occurred through sharing emotional and informational support. (2) Engaging in health-promoting cognitive processes appeared as reframing, self-acceptance, endorsing a positive outlook, and agency and taking responsibility for outcomes. (3) Enacting healthy behavioral practices clustered into modeling sex-positive norms, reducing the risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV, and living well with HIV. (4) Finally, empowering other gay and bisexual youth occurred through role modeling, promoting self-advocacy, and providing encouragement. Future online interventions could advance strengths-based approaches within HIV prevention and care by intentionally building on Black GBMSM’s existing resilience processes. The accessibility and anonymity of online spaces may provide a particularly powerful intervention modality for amplifying resilience among young Black GBMSM.

Background

In the United States, young, Black, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) (ages 13 to 34) experience the highest burden of new Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) diagnoses and the largest disparity compared with White GBMSM in the same age group (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2016). Stigma, discrimination, and social isolation likely contribute to higher HIV incidence among Black GBMSM, who engage in similar or fewer sexual risk behaviors as their White counterparts (Arnold, Rebchook, & Kegeles, Citation2014; Magnus et al., Citation2010; Millett et al., Citation2012; Rosenberg, Sullivan, Dinenno, Salazar, & Sanchez, Citation2011; Van Sluytman et al., Citation2015). Overlapping stigmas related to sexual minority-, race/ethnicity-, and HIV-status pose barriers to engagement in HIV prevention and care as reflected in differential rates of HIV testing, PrEP uptake, HIV treatment, and viral suppression (Arnold et al., Citation2014; Calabrese, Earnshaw, Underhill, Hansen, & Dovidio, Citation2014; Hoots, Finlayson, Nerlander, & Paz-Bailey, Citation2016; Levy et al., Citation2014; Millett et al., Citation2012; Rowan, DeSousa, Randall, White, & Holley, Citation2014; Voisin, Bird, Shiu, & Krieger, Citation2013). Racism, a form of stigma, also contributes to environments that may limit options for Black GBMSM to build relationships and supportive networks (Bauermeister, Citation2012; Hatzenbuehler, O'Cleirigh, Mayer, Mimiaga, & Safren, Citation2011; LeGrand, Muessig, Pike, Baltierra, & Hightow-Weidman, Citation2014; Matthews, Smith, Brown, & Malebranche, Citation2016). Compared to White GBMSM, Black GBMSM are more likely to have Black partners and younger Black GBMSM are more likely to have older partners, with both factors increasing their likelihood of exposure to HIV (Newcomb & Mustanski, Citation2013; Sullivan et al., Citation2015). In summary, stigma contributes to HIV disparities as Black GBMSM are more likely to be exposed to a partner who has HIV and is not virally suppressed, and less likely to: be protected when exposed to HIV, know their HIV status, and receive care. In these contexts, individual-level risk-reduction interventions and improvements in health care services will be insufficient on their own to reverse the disparities in HIV incidence among young Black GBMSM. Indeed, based on 2015 surveillance data, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated a lifetime risk of HIV acquisition of one in two for Black GBMSM if current disease trends continue (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2017).

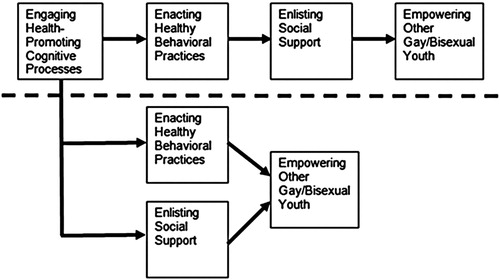

Yet, a risk or deficits-based approach to addressing the HIV epidemic focuses on what is lacking and carries the hazard of reinforcing negative stereotypes and misperceptions that fuel further stigma (Herrick et al., Citation2013; Rowan et al., Citation2014). In contrast, a strengths-based approach builds on young Black GBMSM’s existing individual and community-level strengths (regardless of HIV status), recognizing the remarkable ways in which they are facing and overcoming significant barriers to both HIV prevention and care (Aiyer, Zimmerman, Morrel-Samuels, & Reischl, Citation2015; DiFulvio, Citation2011; Herrick, Stall, Goldhammer, Egan, & Mayer, Citation2014; Hussen et al., Citation2017; Matthews et al., Citation2016). Specifically, resilience is a process through which individuals counter adversity (Masten, Best, & Garmezy, Citation1990) and reduce or avoid negative outcomes (Harper, Bruce, Hosek, Fernandez, & Rood, Citation2014; Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, Citation2000). Harper et al. identified four resilience processes employed by young Black and Latino GBMSM living with HIV (Harper et al., Citation2014). First, following their HIV diagnosis, men engaged in health-promoting cognitive processes including: re-evaluating their life goals, gaining a sense of control through seeking knowledge, and taking responsibility for health outcomes. Second, men enacted healthy behavioral practices to promote their physical health via increasing exercise and improving diet, decreasing drug and/or alcohol use, and practicing safer sex. Third, men enlisted social support from others, including health care providers and organizations, friends and peers, family members, and partners and ex-partners. Finally, having adjusted to living with HIV and developed a positive self-image, men educated and empowered other GBMSM about preventing HIV and living with HIV (Harper et al., Citation2014).

Most research on resilience utilizes static measurement (e.g., scales and surveys) or studies it from the perspective of an individual (e.g., in-depth interviews) (Herrick et al., Citation2014; Woodward, Banks, Marks, & Pantalone, Citation2017). Yet, as described above, resilience is not a static state or trait, but rather involves dynamic, context-specific, and relational processes (Harper et al., Citation2014). Exploring the interactions between Black GBMSM is important for understanding and promoting resilience due to the critical roles of social connectivity and collective identity in resilience processes (DiFulvio, Citation2011; Herrick et al., Citation2014). In a previous study, the anonymity of the internet and the opportunity to interact with other gay/bisexual people improved self-esteem and comfort with sexual orientation, and facilitated sexual orientation identity development and the coming out process of gay and bisexual male adolescents (Harper, Serrano, Bruce, & Bauermeister, Citation2016). Given that Black GBMSM may have restricted networks due to influences of racism and HIV stigma (Newcomb & Mustanski, Citation2013; Sullivan et al., Citation2015), it is important to explore interactions among them. Observing more organic resilience processes exchanged between Black GBMSM would provide insight into how these protective processes are fostered, enacted, and shared. HealthMpowerment.org (HMP) is an internet and mobile phone based intervention that consists of an anonymous online space created with and for young Black GBMSM regardless of HIV status (Hightow-Weidman et al., Citation2015; Muessig, Baltierra, Pike, LeGrand, & Hightow-Weidman, Citation2014). HMP includes forums where participants can react to pre-populated or staff-generated conversations around topics identified through formative research with young Black GBMSM (LeGrand et al., Citation2014; Muessig et al., Citation2013; Muessig et al., Citation2014) or start their own new conversation threads. We initially analyzed these conversations using Harper et al.’s resilience framework to understand how resilience processes were displayed among young Black GBMSM. We then expanded this framework based on the content and nature of the interactions between HMP participants. Ultimately, understanding how resilience processes are shared among young Black GBMSM could inform more strengths-based intervention approaches for improving both HIV prevention and care.

Methods

Parent study

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) of HMP was conducted from 2013 to 2016 in the southeastern U.S., enrolling 474 Black GBMSM aged 18-30 years old who reported condomless anal intercourse with a male partner in the past three months. Forty percent of participants also identified as another race/ethnicity and 42.0% self-reported an HIV-positive status at baseline. Participants were randomized to HMP or an information-only control website and completed follow-up surveys at 3, 6, and 12 months. At enrollment, HMP intervention participants created a log-in and anonymous username for privacy. Participants were asked to utilize HMP for the first 3 months of the study as an active intervention period (parent study primary endpoint). Particpants then had the option to continue using HMP for the remaining 9 months of the follow-up period. The primary outcome of interest in the main study (reported elsewhere) was reduced condomless anal intercourse (Hightow-Weidman et al., Citation2017).

Data sources

A dominant feature of the HMP intervention site was the provision of forums for Black GBMSM to connect and share life experiences and health information (Hightow-Weidman et al., Citation2015; LeGrand et al., Citation2014). Data for the current analysis draws from posts to two areas of the HMP site where RCT participants could interact with each other: The Forum and Getting Real. The Forum was a space where participants could read and contribute to existing conversation threads or start new threads. Getting Real was designed to be a creative space where participants could post and respond to topics with videos, poems, reflections, audio, and pictures. Site guidelines emphasized practicing mutual respect of different life experiences, beliefs, and opinions. Posts in The Forum and Getting Real displayed the HMP username of the poster. Content on the intervention site was also contributed by study staff (including a board-certified infectious disease physician) and site ambassadors (eight Black GBMSM who were paid a modest stipend to regularly contribute content to the site), however content analyzed for this sub-study was limited to RCT participants.

Analysis

During the course of the HMP trial, we observed that more than half of the posts shared by participants included discussion of stigma or discrimination primarily focused on HIV, race/ethnicity, and gender and sexual minority status, prompting a focused analysis of these data. All participant posts and their associated paradata (e.g., username, date stamp, site section) were analyzed using Dedoose online qualitative data software (Version 7, www.dedoose.com). Username was included so that we could analyze trends and themes within and between individual participants over time. We began with a phenomenological approach to analyze multiple forms of stigma and discrimination discussed by young Black GBMSM. Phenomenology focuses on describing commonalities among a given group of participants as they experience a particular phenomenon (Creswell, Citation2012; Patton, Citation2002). From this analysis, resilience emerged as a central theme.

We then conducted a secondary analysis guided by the resilience framework developed by Harper et al., Citation2014 (described above; ) to understand how resilience processes were displayed and fostered through exchanges between young Black GBMSM in this anonymous online space. We completed a second round of coding using Harper et al.’s four primary resilience processes (engaging health-promoting cognitive processes, enacting healthy behavioral practices, enlisting social support, and empowering other gay and bisexual youth) and then reviewed these coded conversations to identify subthemes within each of the four resilience processes and describe the relationships between the processes. Early in the coding process we expanded the code of “enlisting social support” to “exchanging social support” because of the interactive nature of the site, in which participants were both soliciting and providing social support.

Figure 1. Differential progression of resilience among young gay and bisexual men living with HIV as conceptualized in Harper et al Citation2014. Note: Figure reprinted with permission. This figure originally appeared in AIDS Care, published by Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., New Rochelle, NY.

There are a few distinctions of note between Harper et al.’s sample and the online HMP sample. HMP is focused on Black GBMSM (though 35% of those who posted also identify as other race/ethnicities), includes HIV-negative and status unknown MSM, and includes an older age range (18 to 30 years old vs. 17 to 24 years old). In the Harper et al., Citation2014 sample, Black and Latino GBMSM discussed resilience in response to HIV infection, while in the HMP sample we explored the resilience processes of Black GBMSM coping with overlapping stigmas related to sexual minority-, race/ethnicity-, and HIV- status. Based on the contexts described in the Background above, we hypothesized that young Black GBMSM would face many of the same challenges to optimal HIV prevention and care, and that similar resilience processes would be relevant, regardless of HIV status. Another important distinction is that the HMP data were generated in the context of an online intervention setting through anonymous discussions and posts over the course of the two years that the intervention study was open. In contrast, Harper et al.’s model emerges from one-on-one interviews and focuses on describing resilience processes from the perspective of the individual. Adaptation of this framework for the HMP intervention reflects how these resilience processes operated in the context of exchanges between two or more individuals over time.

Results

Demographics

Forty-eight intervention-arm participants, with an average age of 24.3 years, posted stigma-relevant content to HMP. Forty-six percent (22/48) of these participants were living with HIV at baseline, and just over a third (17/48) reported another race or ethnicity in addition to Black/African American. The majority of stigma posters had at least a high school degree (41/48) and were currently employed (32/48), although less than a third reported an annual income at or above a living wage for their state (13/48) (Glasmeier, Citation2017).

Resilience processes in the HMP online community

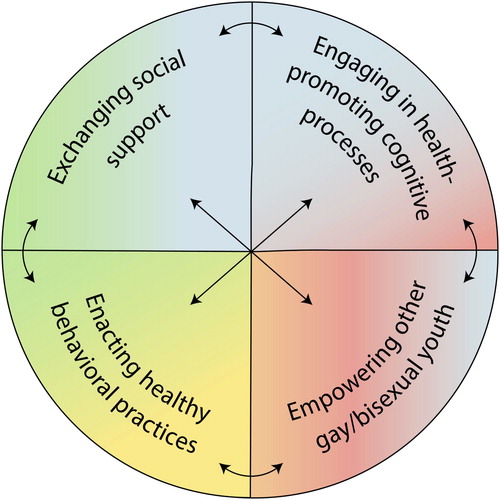

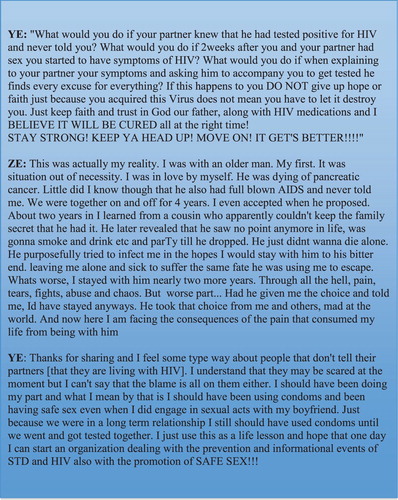

Results are organized by the four primary resilience processes described above: exchanging social support, engaging in health-promoting cognitive processes, enacting healthy behavioral practices, and empowering others. These four processes and their subthemes are presented individually below, however the majority of conversations, and even individual posts, were coded with multiple resilience processes and subthemes. Reflecting this, our reconceptualization of the original framework by Harper et al. is presented in . We chose to set aside the sequential aspect of the Harper et al. model to reflect how the processes interacted as displayed in these conversations. The bidirectional arrows throughout the circle indicate how the resilience processes exchanged among participants appeared to build on and reinforce one another. The blended colors indicate the overlap of resilience processes as they frequently occurred together and were at times challenging to distinguish. Demonstrating this overlap, presents an excerpt from a conversation that features all four resilience processes and illustrates how multiple processes are integrated within a single post and conversation. We refer to the conversation in throughout the Results section for additional examples of themes and subthemes.

Exchanging social support

Across conversations on the HMP intervention, exchanging various forms of social support was the most common resilience process. Prominent subthemes within this resilience process included exchanging: a) emotional support and b) informational support.

A number of Black GBMSM shared difficult experiences from their lives that ranged from major life events to daily experiences of stigma and discrimination. As seen in the sample dialogue () and the excerpt below, in response, participants exchanged emotional support, advice, and encouragement.

Two weeks after my 24th Bday the man I thought was my father asked for a DNA test. The test showed that we are not related. She [my mother] finally admits to me that im a product of rape. Im already having a hard time dealin with being Hiv+, and having several different mental health issues. I really don’t know how to deal with this … I need some advice.

You have people that care about you. The best way to get through something that has you down is to talk to someone professional about it or to talk to someone or people that are close to you. If you feel as though you are alone then you have to find strength in yourself to push forward whether it be mentally, physically, or spiritually, you’ll get through it! (Forum 140)

Participants also posed direct questions to the HMP community seeking specific informational support. These conversations often reflected participants’ experiences and challenges as young Black GBMSM and ranged from advice for finding LGBTQ-friendly health care services to life decisions such as what college to attend.

I have my prescription for PrEP finally … Dunno how much it will be after everything is put in place so I will wait till I get paid just in case.

I’m looking [for a PrEP provider] but no luck

@MA are you having trouble finding a provider that’s in your area? And MK, if you have insurance plus the Gilead card you may not have to pay anything … .

I have insurance, my concerns are: what are some general side effects [of PrEP] and are they anything that will keep me out of work or restrict the normal day to day operation of a working male? (Forum 258)

What are the advantages and disadvantages of attending a Predominately White Institution [PWI] vs. Historically Black College & University [HBCU] as a member of the glbt community?

To answer this question I feel like you’d really have to narrow it down to the specific schools … but I’ll just mention a few things based on my personal experience … HBCUs are rooted in the history of protecting and taking care of its students since Blacks weren’t allowed at PWIs back in the day … PWI or HBCU, I’m just a proponent of going to college at all … (Getting Real 31)

As seen in the passages above and the sample dialogue in , across exchanges of emotional and informational social support, participants’ responses employed multiple strategies including offering advice, non-directive support, reassurance, understanding, empathy, and encouragement. These supportive posts also expressed solidarity (as seen in Forum 140) and reflected aspects of shared identity as Black GBMSM (as seen in Getting Real 31).

Engaging in health-promoting cognitive processes

Health-promoting cognitive processes were commonly displayed in participants’ posts and could be grouped into four primary types: a) reframing; b) self-acceptance; c) endorsing a positive outlook; and d) agency and taking responsibility for outcomes. Often, multiple resilience cognitive processes were displayed within a single post or conversation.

A central theme within health-promoting cognitive processes focused on cognitive reappraisal and reframing of circumstances and thought processes in order to change one’s emotional response (Gross, Citation1998). In these conversations individuals shared how they applied reframing in their own lives, and also actively practiced reframing of life situations shared by other participants. Examples of reframing included thinking about HIV as a chronic health condition versus a death sentence, and viewing relationship troubles in a new light:

I went through the same thing [intractable depression] when I received my [HIV] diagnosis … It gets better just surrounding yourself with positive people … I filled my mind with information about what I was fighting with. Keep your head up smile.

I was finally diagnosed July 2013 … It sent me into the deepest depression I've ever been in … You've got to first make peace with what is … Poz or not, You do not live with HIV, hiv lives with You … it's only a chronic health condition. Nothing more. You have alot of life ahead of you. The choice is yours how you wanna spend it luv. (Forum 33)

If he does not show interest, dont waste your time … let him be, and you live on … as you continue to grow and love yourself like you deserve to be loved. Then you will have a knowledge of how your supposed to be treated based on your experiences with guys like this one … He's not a bad guy for not wanting you. He is really doing you a favor, just simply not the one for YOU … (Forum 5)

Discussions also demonstrated participants’ expressions of resilience through self-acceptance and rejecting the need for approval from others. In some cases this process was part of reframing and reappraisal. Self-acceptance was particularly apparent as participants grappled with experiences of stigma and discrimination from family, partners, and broader society, including related to their sexual identity:

Do you feel bad being gay because it is unnatural and has huge risk for incurable diseases? I always felt bad for being gay and it isn’t fulfilling because I want children and respect from my family and community. It feels like I am a waste being gay.

Well I feel like myself, this is who I really am inside I'm a gay African American male and I love who I am I'm a unique human (Forum 88)

I hate feeling like my own family does not want me around … this is me so take it or leave it. Be Proud of Who You Are!

Before I told my dad I was gay, we was very close we did everything together. Whenever I came out that I was gay, everything stopped … we went from seeing each other everyday to now I've not seen or heard from my dad in about 3 years. I feel as though he is not worried about my happiness however worried about what people may say about him. But I've accepted myself and I love me, so I feel that my dad is missing out on my life because of who I choose to love. (Getting Real 23)

As displayed within the example excerpts for the first two subthemes, participants also displayed cognitive resilience through explicitly endorsing a positive outlook, including emphasizing the good in their lives, hoping and planning for continued improvement, and expressing optimism about the future even in the face of current struggles.

2013 was definitely the most difficult I've had thus far. Between my status change, moving states, enrolling in school, and changing social circles there were a lot of ups and downs. This year I'm gonna try and focus on the positive- my family who supports me through my status change, my health that's unwavering, and my future that's gonna be bright as long as I focus. (Forum 42)

I believe that when we start to think about trust as something unique to every relationship and connection in our lives it becomes easier to trust. I look at it like each relationship I hold, be it friend, family, intimate, etc. is a new trust just like planting a new tree. You have to work at it and cultivate it, but just because one tree gets uprooted doesn’t mean another can’t flourish. (Forum 34)

Finally, Black GBMSM described beliefs, actions, and intentions that reflected personal agency in taking responsibility for circumstances or outcomes in their lives. This cognitive process was commonly visible in descriptions of structural problems such as poverty, homelessness, and stereotypes about Black GBMSM, but was also reflected in more day-to-day actions such as discussing health goals and how to achieve them. This theme also appears in the sample conversation in .

I'm getting a job and actually budgeting and saving my money. I'm never going to experience poverty and homelessness again. But I'm going to start exploring my more artistic side and working on being myself with boldness. (Forum 48)

Enacting healthy behavioral practices

Participants shared and encouraged a range of healthy behavioral practices on HMP. While these discussions touched on all areas of their lives, the majority of conversations could be grouped into three sub-themes: a) modeling sex-positive norms; b) reducing the risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV; and c) living well with HIV.

Discussions around sex and sexuality modeled sex-positive norms, covering a variety of topics including keeping sex exciting in long-term relationships, sharing sexual fantasies, and exploring how one’s current and ideal sex life differed. The two examples below highlight participants’ comfort in having open discussions about sex and sexuality.

I don't see anything wrong with travelling for sex. I was a student at [university redacted] and had a room to myself, so I've had people travel to me from all over the state. (Forum 293)

Most of these are great ways to spice things up a bit. Im an exhibitionist and im also a voyeur. Watching porn together is good … but watching someone have sex practically in front of you is a whole other thing. (Forum 13)

A number of conversations discussed norms about sex and strategies for protecting one’s health including encouraging regular HIV testing, HIV status discussions, condom use, and PrEP use:

You two are the first people EVER IN MY LIFE that said, no condom … ok oral [sex] it is

There's a lot of people out here with stds and HIV that won't come out and say it up front, so if you want to stay clean and safe you just have to make sure you have the maturity to speak up and say, “you got a condom?” (Forum 195)

Before having a sexual encounter … do you disclose your status or talk about getting tested? … For me I go through the whole process of asking/telling as well … what are some of your methods for disclosure?

I find it easier to have a conversation about testing/status when I am dating someone … I like to bring it up as a way to indicate that I’m ready to get down to business … I put the last date I was tested on my A4A [Adam4Adam] profile, and I am more apt to talk to a guy who also has his last testing date listed. (Forum 111)

Health behavior discussions also revealed reflections on living well with HIV across physical, social, and emotional health. These conversations included participants of all HIV statuses and considered both personal experiences as well as people, events, and trends outside of HMP.

I am not fond of the HIV Equal theme. A better representation would be if we were to be depicting ourselves as equals, but being HIV - and HIV + are two very different things … if you continue to preach that there is an HIV =, people will take it that way. “The disease don't mean anything” could become the primary thought … I wouldn't consider myself HIV = to anything. I'm proud of my status because it let's me know that I can handle anything that is thrown my way. (Forum 268)

I've been diagnosed for a year now and I have found that people that are educated about HIV are more accepting than those who are even a tad bit ignorant about their health period. The guy Im dating now is ok with taking a preventive Medicine to keep us both safe and we still practice safe sex. (Forum 32)

Empowering other gay and bisexual youth

As young Black GBMSM on HMP exchanged social support, engaged in health-promoting cognitive processes, and enacted healthy behavioral practices, they not only empowered each other, but also extended these processes outside of the intervention. In examining posts and conversations that featured language around empowering others, three types of subthemes emerged: a) role modeling, b) promoting self-advocacy, and c) providing encouragement.

Participants’ intersectional identities as Black GBMSM and the multi-layer stigma and discrimination they experienced was often discussed in the context of a scarcity of gay role models – especially Black, gay role models – in their communities and the media. Conversations included sharing personal role model stories, countering stereotypes, and celebrating the emerging visibility of Black gay love.

We do not know of any lasting gay relationships. All of our gay friends have all had failing relationships. Men women even celebrities that get married in the lifestyle seem to get divorces. I don't want to live my life alone or believing that I will never find my soulmate. Does anyone believe that gay relationships can last?

Gay relationships can last, it just depends on the work you put into it and if both are being honest and communicate properly. Me and my bf have been together for 6yrs now, will be 7 in May, our mutual friend has been in a relationship with his bf for about 5 + yrs … If you want to talk about celebrities: Neil Patrick Harris and David Burka have been together for over a decade … it takes time and patience … don't give up on relationships. (Forum 144)

I love this show [Empire]. I’m so glad Jamal has a black boyfriend now, because … it’s so rare to see black gay couples on television. It seems like the only way they can put black gay men on tv is if they have this white lover. I’m all for interracial relationships, but it’s nice to see black love sometimes. (Forum 163)

A second subtheme within the resilience process of empowering others focused on promoting self-advocacy. These conversations centered around encounters with authority figures (e.g., health providers, police), as well as with peers (e.g., insisting on condom use, standing up to discrimination based on race or sexual orientation).

I am always honest with my health providers about my sexual habits. I don't take any chances with my health. While I haven't faced any out and out discrimination, I did have an uncomfortable incident the last time I went to get a physical. I told the nurse that I was not in a monogamous relationship, have sex with men, that I always used condoms, and that I get tested regularly. But I noticed that in the summary of the visit, she still put me down as “engaging in high risk sexual behavior.” I felt like that was more in response to the people I sleep with than anything else I said. To be honest, as long their judgment doesn’t get in the way of my receiving services, I could care less what they think. (Forum 81)

Sadly, all the circumstances involve white cops killing blacks and the cops getting off with no repercussions. The black community already across the country have a thing against cops since before the Rodney King incident … I think the communities need to have sit downs with law enforcement and come up with some kind of relationship otherwise these incidents will become more frequent in the future. (Forum 125)

Finally, participants’ posts and conversations overwhelmingly featured words of encouragement directed toward specific individuals or the broader site membership. This encouragement included affirmations, concrete advice for action, and motivational language.

I have been trying to find the right guy for me, and I have not been successful at all. For some reason, all I seem to attract is the “Mr. Right Now” type of guy. I am not wanting to give up, [but] it is really becoming an option. No one wants to be in a relationship anymore, but that's all I really want. Where do I go other than dating sites and apps to talk to guys?

It's hard to trust people now a days even when they want a relationship back as well … It's a tough life to be honest, but it's all about taking risks and hoping that's it's the right decision and trusting your gut. Definitely don't limit yourself to just your living area. Another city, county or state even. Broaden your horizons and try to make sure they're honest from the beginning (Forum 137)

Discussion

We analyzed conversations among young Black GBMSM enrolled in the HMP online intervention to understand how resilience processes were displayed, shared, and encouraged between participants. Our findings affirm the overarching resilience framework put forth by Harper et al. and also extend it by illustrating the breadth of roles peer-level support played in fostering resilience. We also identified new subthemes that emerged from examining these between-person interactions. Within the cognitive resilience process, we identified self-acceptance as a central theme in Black GBMSM’s interactions. This finding aligns with work by DiFulvio (Citation2011), who emphasize the importance of affiliation and finding similar others for self-affirmation. As participants were able to connect with similar others through HMP, they shared self-affirmation and encouraged each other in rejecting judgmental or stigmatizing views. Within enacting health-promoting behaviors, we identified modeling sex-positive norms as a core subtheme of resilience. The tone and anonymity offered by HMP might have facilitated the expression of sex-positive norms and generated more candid questions and discussions than might have been provided in-person. This aspect of resilience seemed particularly important for the young Black GBMSM in this study who had limited access to people or spaces where they could discuss sex and sexuality candidly and without judgement (Harper et al., Citation2016). As seen in the HMP conversation excerpts, we found multiple components of resilience processes organically integrated within many of participants’ posts. Our findings extend the theoretical literature on resilience and could inform future quantitative studies to develop and test hypothesized relationships between constructs in these resilience processes, including their relative contributions and directionality.

Observing the resilience processes displayed in conversations on the HMP site has important implications for intervention. This and other studies have found that resilience processes help buffer the impact of stigmatizing contexts on Black, GBMSM health (Hussen et al., Citation2017). Interventions that create spaces where communities can connect and support one another could leverage resilience processes by intentionally including program objectives that foster exchanging social support, engaging in health promoting cognitive processes, enacting healthy behavioral practices, and empowering others. Interventions should also measure these resilience processes as part of evaluation, both to assess efficacy and to investigate how resilience processes are best facilitated by interventions. The discussion topics and content generated through HMP’s forums also highlight salient issues that could be included in the design of HIV prevention and care programs for Black GBMSM. The use of these participant-generated data might complement researcher-led formative methods (e.g., focus groups, in-depth interviews) by reflecting what Black GBMSM actually discussed when provided a platform with the flexibility (and anonymity) to choose how and what they contributed.

The strengths of this study stem from the nature of the HMP data and the subthemes we identified within the resilience processes. First, observing resilience processes as they are displayed within an interactive forum facilitated viewing the social, dynamic nature of resilience and suggests ways in which this form of social support may strengthen individual and interpersonal resilience (Herrick et al., Citation2014; Meyer, Citation2010). Increasingly, community engagement and interpersonal interactions take place online, particularly among stigmatized groups like Black GBMSM who may have diminished access to affirming identity-bound communities in their geographic area (Harper et al., Citation2016; LeGrand et al., Citation2014). Witnessing and analyzing Black GBMSM’s resilience processes provides unique insight into how these processes may buffer the effects of stigma and discrimination. Second, our results provide examples of intersectional resilience among sexual and racial/ethnic minorities experiencing HIV stigma. Observing these resilience processes on the HMP site allowed us to see how young Black GBMSM adapt resilience practices of both the Black and gay community for their intersectional identities. Third, our adapted model built on the concept of resilience processes as a continuum (Harper et al., Citation2014). The flexibility of the HMP intervention design allowed participants at different places along a resilience continuum to interact and learn from each other. Conversations around HIV status and diagnoses provide particularly salient examples of this as the intervention site includes youth regardless of HIV status (living with HIV, not living with HIV, status unknown) or length of time living with HIV.

This study also has several limitations. First, it can be difficult to interpret the tone and intention of online data. To improve our ability to understand each participant's posting habits in greater context, we read data grouped by conversation and also grouped by participant. Second, resilience processes identified in this dataset may not be representative of other Black GBMSM as HMP participants could be unique given their interest in participating in the trial and actively contributing posts on the site. However, even if the HMP contributors are unique – these types of individuals could serve as thought leaders in their communities and their strengths could be utilized in prevention and care interventions (online and otherwise) as resilience champions. Third, it is unclear how the resilience processes we observed connect to users’ actual health behaviors. In other words, someone who talks about feeling empowered to use condoms may not actually do so. Fourth, we considered but ultimately chose not to separately analyze conversations by who initiated them (i.e., HMP program staff, pre-populated, participants). We do not think this would significantly change our findings as the staff topics and pre-populated conversations all drew directly from earlier formative and HMP pilot work with young Black GBMSM. Furthermore, participants regularly took staff-initiated conversations in new directions or referenced other HMP conversations when posting. Future studies could compare how the level and nature of structure provided within this kind of online space impacts the content and evolution of participant contributions (Blackburn et al., Citation2017).

Even as we emphasize the resilience processes displayed in this intervention, we also echo Matthews et al. who state: “resiliency in the face of adversity is important, but it also places undue burden on those negatively affected by those very adversities” (Matthews et al., Citation2016, p. 812). Indeed, the conversations of HMP participants displayed both resilience processes and significant social and structural adversities (past, present, and future) that need to be addressed in order to make progress in reducing disparities in HIV prevention and care for young Black GBMSM. As resilience gains ground within the field, it is critical that the research, provider, and public health communities continue to work toward dismantling social and structural stigma and discrimination.

Acknowledgements

We thank the investigators, advisory board, study participants, staff, and site ambassadors of the healthMpowerment intervention for their engagement in creating the HMP community. Karina Soni created graphics for this manuscript. Karina Soni and Seul Ki Choi assisted with data management. This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH093275, PI Hightow-Weidman; and R21MH105292, PIs Muessig and Bauermeister). The views expressed herein are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the stance of the funding agency.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aiyer, S. M., Zimmerman, M. A., Morrel-Samuels, S., & Reischl, T. M. (2015). From broken windows to busy streets: A community empowerment perspective. Health Education & Behavior, 42(2), 137–147. doi: 10.1177/1090198114558590

- Arnold, E. A., Rebchook, G. M., & Kegeles, S. M. (2014). ‘Triply cursed': Racism, homophobia and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence and disclosure among young black gay men. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 16(6), 710–722. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.905706

- Bauermeister, J. A. (2012). Romantic ideation, partner-seeking, and HIV risk among young gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(2), 431–440. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9747-z

- Blackburn, N., Dong, W., LeGrand, S., Sallabank, G., Hightow-Weidman, L.B., Barry, M., Pulley, D., & Muessig, K.E. (2017). Structure and agency in an online space: A theoretical approach to online community in an HIV intervention among young black men who have sex with men. APHA 2017, November 4–8, 2017. Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

- Calabrese, S. K., Earnshaw, V. A., Underhill, K., Hansen, N. B., & Dovidio, J. F. (2014). The impact of patient race on clinical decisions related to prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): Assumptions about sexual risk compensation and implications for access. AIDS and Behavior, 18(2), 226–40. doi:10.1007/s10461-013-0675-x

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). HIV surveillance report, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2015-vol-27.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). CDC Fact Sheet: HIV among African Americans. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/cdc-hiv-aa-508.pdf

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- DiFulvio, G. T. (2011). Sexual minority youth, social connection and resilience: From personal struggle to collective identity. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 72(10), 1611–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.045

- Glasmeier, A. K., & Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (2017). Living wage calculator. Retrieved from http://livingwage.mit.edu/

- Gross, J. J. (1998). Antecedent and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 224–237. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.224

- Harper, G. W., Bruce, D., Hosek, S. G., Fernandez, M. I., & Rood, B. A. (2014). Resilience processes demonstrated by young gay and bisexual men living with HIV: Implications for intervention. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 28(12), 666–676. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0330

- Harper, G. W., Serrano, P. A., Bruce, D., & Bauermeister, J. A. (2016). The internet's multiple roles in facilitating the sexual orientation identity development of gay and bisexual male adolescents. American Journal of Men's Health, 10(5), 359–376. doi: 10.1177/1557988314566227

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., O'Cleirigh, C., Mayer, K. H., Mimiaga, M. J., & Safren, S. A. (2011). Prospective associations between HIV-related stigma, transmission risk behaviors, and adverse mental health outcomes in men who have sex with men. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 42(2), 227–234. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9275-z

- Herrick, A. L., Stall, R., Chmiel, J. S., Guadamuz, T. E., Penniman, T., Shoptaw, S., … Plankey, M. W. (2013). It gets better: Resolution of internalized homophobia over time and associations with positive health outcomes among MSM. AIDS and Behavior, 17(4), 1423–1430. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0392-x

- Herrick, A. L., Stall, R., Goldhammer, H., Egan, J. E., & Mayer, K. H. (2014). Resilience as a research framework and as a cornerstone of prevention research for gay and bisexual men: Theory and evidence. AIDS and Behavior, 18(1), 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0384-x

- Hightow-Weidman, L. B., LeGrand, S., Simmons, R., Egger, J., Choi, S. K., & Muessig, K. E. (2017). Healthmpowerment: Effects of a mobile phone-optimized, internet-based intervention on condomless anal intercourse among young black men who have sex with men and transgender women. #WEPEC1001. 9th ias conference on HIV science (IAS 2017), Paris, France. July, 2017.

- Hightow-Weidman, L. B., Muessig, K. E., Pike, E. C., LeGrand, S., Baltierra, N., Rucker, A. J., & Wilson, P. (2015). Healthmpowerment.org: Building community through a mobile-optimized, online health promotion intervention. Health Education & Behavior, 42(4), 493–499. doi: 10.1177/1090198114562043

- Hoots, B. E., Finlayson, T., Nerlander, L., & Paz-Bailey, G. & National HIV Behavioral Surveillance Study Group. (2016). Willingness to take, use of, and indications for pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men-20 US cities, 2014. Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 63(5), 672–7. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw367

- Hussen, S. A., Harper, G. W., Rodgers, C. R. R., van den Berg, J. J., Dowshen, N., & Hightow-Weidman, L. B., on behalf of the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2017). Cognitive and behavioral resilience among young gay and bisexual men living with HIV. LGBT Health, 4(4), 275–282. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2016.0135

- LeGrand, S., Muessig, K. E., Pike, E. C., Baltierra, N., & Hightow-Weidman, L. B. (2014). If you build it will they come? Addressing social isolation within a technology-based HIV intervention for young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Care, 26(9), 1194–1200. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.894608

- Levy, M. E., Wilton, L., Phillips, G., Glick, S. N., Kuo, I., Brewer, R. A., … Magnus, M. (2014). Understanding structural barriers to accessing HIV testing and prevention services among black men who have sex with men (BMSM) in the United States. AIDS and Behavior, 18(5), 972–996. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0719-x

- Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164

- Magnus, M., Kuo, I., Phillips, G., Shelley, K., Rawls, A., Montanez, L., … Greenberg, A. E. (2010). Elevated HIV prevalence despite lower rates of sexual risk behaviors among black men in the district of Columbia who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 24(10), 615–622. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0111

- Masten, A. S., Best, K. M., & Garmezy, N. (1990). Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology, 2(4), 425–444. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400005812

- Matthews, D. D., Smith, J. C., Brown, A. L., & Malebranche, D. J. (2016). Reconciling epidemiology and social justice in the public health discourse around the sexual networks of black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 106(5), 808–814. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.303031

- Meyer, I. H. (2010). Identity, stress, and resilience in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals of color. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(3), 442–454. doi: 10.1177/0011000009351601

- Millett, G. A., Peterson, J. L., Flores, S. A., Hart, T. A., Jeffries, W. L. t., Wilson, P. A., … Remis, R. S. (2012). Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: A meta-analysis. Lancet, 380(9839), 341–348. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60899-x

- Muessig, K. E., Baltierra, N. B., Pike, E. C., LeGrand, S., & Hightow-Weidman, L. B. (2014). Achieving HIV risk reduction through HealthMpowerment.org, a user-driven eHealth intervention for young black men who have sex with men and transgender women who have sex with men. Digital Culture & Education, 6(3), 164–182. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25593616

- Muessig, K. E., Pike, E. C., Fowler, B., Legrand, S., Parsons, J. T., Bull, S. S. … Hightow-Weidman, L. B. (2013). Putting prevention in their pockets: Developing mobile phone-based HIV interventions for Black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 27(4), 211–222. doi:10.1089/apc.2012.0404

- Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2013). Racial differences in same-race partnering and the effects of sexual partnership characteristics on HIV risk in MSM: A prospective sexual diary study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 62(3), 329–33. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e5f8c

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Rosenberg, E. S., Sullivan, P. S., Dinenno, E. A., Salazar, L. F., & Sanchez, T. H. (2011). Number of casual male sexual partners and associated factors among men who have sex with men: Results from the national HIV behavioral surveillance system. BMC Public Health, 11, 189. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-189

- Rowan, D., DeSousa, M., Randall, E. M., White, C., & Holley, L. (2014). "We're just targeted as the flock that has HIV": Health care experiences of members of the house/ball culture. Social Work in Health Care, 53(5), 460–477. doi:10.1080/00981389.2014.896847

- Sullivan, P. S., Rosenberg, E. S., Sanchez, T. H., Kelley, C. F., Luisi, N., Cooper, H. L., … Peterson, J. L. (2015). Explaining racial disparities in HIV incidence in black and white men who have sex with men in atlanta, GA: A prospective observational cohort study. Annals of Epidemiology, 25(6), 445–54. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.006

- Van Sluytman, L., Spikes, P., Nandi, V., Van Tieu, H., Frye, V., Patterson, J., & Koblin, B. (2015). Ties that bind: Community attachment and the experience of discrimination among black men who have sex with men. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 17(7), 859–872. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1004762

- Voisin, D. R., Bird, J. D., Shiu, C. S., & Krieger, C. (2013). "It's crazy being a Black, gay youth.” Getting information about HIV prevention: A pilot study. Journal of Adolescence, 36(1), 111–119. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.09.009

- Woodward, E. N., Banks, R. J., Marks, A. K., & Pantalone, D. W. (2017). Identifying resilience resources for HIV prevention among sexual minority men: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 21(10), 2860–2873. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1608-2