ABSTRACT

Diagnosing symptoms of psychological distress can be challenging in migrants living with HIV (MLWH) living in Western Europe. We evaluated the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) as a screening tool for psychological distress. Additionally, the association between psychological distress and adherence to combination Antiretroviral Therapy (cART) was determined. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, psychosocial variables, and self-reported adherence to cART data were collected. 306/352 participants completed the HADS. A HADS+ (≥15, at risk for psychological distress) was found in 106/306. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) was completed by 60/106. The HADS was repeated in 58 participants as the time between the first HADS and the CIDI was more than three months. In 21/37 participants with a HADS+ (57%) within three months before the CIDI a diagnosis of depression or anxiety disorder based on the CIDI was found. Participants with a HADS+ were more likely to be non-adherent (71.3% vs. 43.6%). In a large group of MLWH in the Netherlands, 35% were at risk for symptoms of psychological distress. The HADS seems to be a suitable screening tool for MLWH.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Since the introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART), life expectancy of people living with HIV (PLWH) has greatly improved (May et al., Citation2014; Trickey et al. Citation2017). Subsequently, the focus of care for PLWH is not merely on their quantity of life years to gain, but more and more on their quality of life.

Mental health is an important issue. Symptoms of anxiety and depression are common among PLWH. In fact, 33% of a large sample of PLWH in Canada and Western Europe were screened positive for symptoms of anxiety (Robertson et al., Citation2014). Additionally, a recent meta-analysis showed prevalence’s of depressive symptoms in 12.8–78% of PLWH living in low, middle and high-income countries (Uthman, Magidson, Safren, & Nachega, Citation2014). Presence of symptoms of anxiety or depression (“psychological distress”) has been linked with decreased adherence to ART, poor HIV treatment outcomes, and mortality (Brandt et al., Citation2017; Campos, Guimaraes, & Remien, Citation2010; Gonzalez, Batchelder, Psaros, & Safren, Citation2011; Langebeek et al., Citation2014; Shacham, Nurutdinova, Satyanarayana, Stamm, & Overton, Citation2009; Todd et al., Citation2017; Uthman et al., Citation2014). PLWH with anxiety symptoms can have difficulty engaging in behaviors that are health promoting (Shacham et al., Citation2009). Depressive symptoms, such as loss of interest, diminished concentration, feelings of worthlessness, and recurrent thoughts of death can negatively influence the self-management activities required by HIV treatment (Gonzalez et al., Citation2011).

In the Netherlands, 41% of the people living with HIV are immigrants and most frequently originate from Sub Saharan Africa (36%) and Latin America (18%)(Van Sighem et al., Citation2013). This is a group of special attention as they, being immigrants and living with HIV, might be even more at risk of symptoms of anxiety and depression. In fact, previous studies have reported that immigrants (regardless of their HIV status) in Europe are more prone to certain psychiatric disorders due to the process of migration (Bhugra et al., Citation2014). This is also shown at a more local level in the Netherlands as immigrants have shown a higher prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders compared to the native Dutch population (de Wit et al., Citation2008). Among immigrant people living with HIV (MLWH) from outside of Western Europe, poorer treatment adherence, more virological failure, and poorer psychosocial outcomes compared to PLWH born in Western Europe have been found (Feuillet et al., Citation2017; Monge et al., Citation2013; Nellen et al., Citation2009; Staehelin et al., Citation2012; Sumari-de Boer, Sprangers, Prins, & Nieuwkerk, Citation2012). For example, one study reported symptoms of depression in 38% of the MLWH compared to 12% in Dutch PLWH (Sumari-de Boer et al., Citation2012). In this study, depressive symptoms were associated with viral load but not with adherence. However, to our knowledge no other studies have reported on the association between psychological distress and adherence to HIV-treatment in MLWH in Europe.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a screening tool that has been developed to measure symptoms of anxiety and depression in a general medical population in 1983 (Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983). It contains 14-items that focus on anxiety and depression. This tool can be self-administered and during the last decades it has been translated into multiple languages and validated within different populations around the world (Bjelland, Dahl, Haug, & Neckelmann, Citation2002; Herrmann, Citation1997). Diagnosing anxiety or depressive disorders or symptoms in a uniform matter can be challenging in MLWH living in Western Europe due to language and cultural barriers. The HADS might be a rapid screening tool that HIV care providers can administer during their consultations, or that can be self-administered. However, whether the HADS can be used among non-Western MLWH living in Western Europe has yet to be determined.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate whether the HADS can be used in standard care of MLWH to measure psychological distress. The HADS was compared with the Composite Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) which was used as a “gold standard” (WHO, Citation2017). Since the association between depressive disorders and treatment adherence in MLWH has not been extensively studied, the association between psychological distress and treatment adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) was determined.

Materials and methods

Study population

Between November 2012 and July 2013, a total of 352 patients from the outpatient clinics of the two Rotterdam HIV treatment centers (Erasmus University Medical Center and Maasstad Hospital) were included in the ROtterdam ADherence (ROAD) Project. This study was set up to investigate risk factors for non-adherence to HIV treatment in MLWH (Been et al., Citation2016). Eligible participants had to be first or second generation immigrants, aged 18 years or older, diagnosed with HIV, and had to be sufficiently fluent in one of the following languages: Dutch, English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese.

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus University Medical Center. Written informed consent was provided by all participants prior to participation.

Data collection

Sociodemographic and psychosocial data was collected through both the medical chart and an interviewer administered questionnaire (Been et al., Citation2016). Characteristics of all participants in the ROAD-project have been presented previously (Been et al., Citation2016). In short, the eight-item Medical Outcomes Study Socials Support Survey (mMOS-SS) was used to assess experienced social support (Moser, Stuck, Silliman, Ganz, & Clough-Gorr, Citation2012). To assess the amount of internalized HIV-related stigma experienced, the six-item Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale was used (Kalichman et al., Citation2009). HIV-treatment adherence self-efficacy was assessed through the 12-item HIV Treatment Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale (HIV-ASES) (Johnson et al., Citation2007). The 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) was used to determine physical and mental quality of life (Ware Jr., Kosinski, & Keller, Citation1996). Self-reported adherence to cART was measured through a four-item measure developed from adherence questions used in previous studies (Been et al., Citation2016). Data on HIV-RNA, CD4 cell count, and cART use were collected from the ATHENA national observational HIV cohort database (the Dutch national HIV registry of HIV treatment centers). When incomplete, data were cross-checked with medical records.

Symptoms of anxiety or depression were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983). In this 14-item questionnaire focusing on feelings in the past seven days, seven items focus on anxiety (HADS-A; e.g., “I get a sort of frightened feeling as if something awful is about to happen”) and seven items on depression (HADS-D; e.g., “I feel cheerful”). It can be self-administered and it takes about five minutes to complete the questionnaire (Stern, Citation2014). Each item can be answered on a four-point Likert scale and therefore the possible score range for each subscale is 0–21. Both scores can be combined to produce one scale that can be used to screen for general psychological distress, the total HADS score. As the total HADS score, rather than the score on the depression subscale, was shown to have the highest positive predicting value in detecting an psychiatric disorder in a previous study, we choose to focus on the total HADS score (Spinhoven et al., Citation1997). A higher score indicates higher levels of psychological distress and a HADS score ≥15 indicates psychological distress (Ibbotson, Maguire, Selby, Priestman, & Wallace, Citation1994; Kugaya et al., Citation2000; Roth et al., Citation1998). The HADS was offered to all 352 HIV+ migrants in Dutch, English, French, and Spanish. Similar to the general questionnaire, the HADS was interviewer administered. Due to logistical challenges, in 51 participants the HADS was completed >100 days after the general questionnaire.

Participants with a HADS score ≥15 (HADS+) were invited for an appointment to take the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). The CIDI is a structured interview designed to be used by trained lay interviewers for the assessment of mental disorders according to the definitions and criteria of ICD-10 and DSM-IV (Booth, Kirchner, Hamilton, Harrell, & Smith, Citation1998; Michigan, Citation2017; Robins et al., Citation1988; WHO, Citation2017). It has been used as a “gold standard” in previous studies. The CIDI lifetime version 2.1 was used to confirm the indication of psychological distress as a result from the screening with the HADS (Penninx et al., Citation2008). This version focusses on Dysthymia, Major Depressive Disorder, General Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, Social Phobia, and Agoraphobia. The CIDI could only be administered in Dutch or English. We aimed to administer the CIDI within three months after the HADS was completed. This was not possible in almost all participants and therefore the HADS was completed again just before the CIDI was administered. Regardless of the results from the second HADS the CIDI was administered in all participants with an initial HADS+. The interviewers who administered the CIDI had received a formal training (GGZ inGeest, VU University Medical Center). When the results from the CIDI were indicative for depression or anxiety disorder, participants were offered a consultation with a psychiatrist (care as usual) and their treating HIV physician was informed.

Statistical analyses

Reliability analysis of the HADS was performed by measuring the internal consistency using Cronbach’s α for both the subscales of the HADS and the total scale. Categorical data between groups was compared using Chi2 and Fisher-Freeman-Halton-Exact tests. To compare continuous data, T-tests and the Mann–Whitney tests were used when appropriate. Patients were defined as cART experienced when they used cART >6 months prior to inclusion. An undetectable viral load was defined as HIV1-RNA or HIV-2 RNA <50 copies/ml. Participants who had missing data on the HADS were excluded.

The association between the HADS and CIDI was determined using the Chi2 test.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

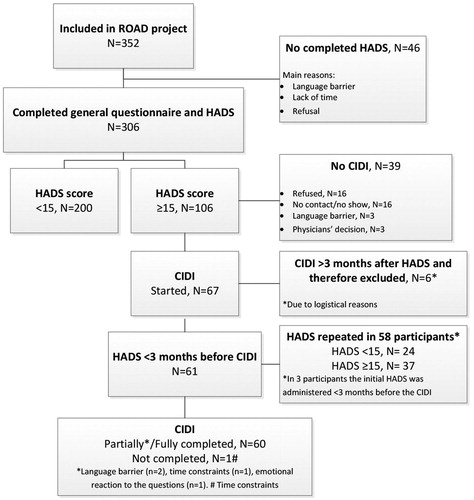

The HADS was completed by 306 patients: 240 in Dutch, 49 in English, 10 in French, and 7 in Spanish (). Mean age of all participants was 41.7 years (sd, 10.5) and the majority were men (57%). Most originated from Sub Saharan Africa (38.2%), followed by Latin America (23.5%), the Caribbean (19.9%), and then regions categorized as “other” (18.3%) (). These patients were not statistically significantly different in baseline characteristics when compared to the 46 patients that did not complete the HADS (data not shown). Reasons for not completing the HADS were mainly: having a language barrier, lack of time after completing the general questionnaire, and refusal. A total of 106/306 of the participants (34.6%) had a HADS+ (score of ≥15) ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics and psychosocial variables.

In 51 participants, the HADS was completed >100 days after the general questionnaire. When comparing this group with the participants that completed the HADS <100 days after the general questionnaire, they were older (45 years vs. 41 years, p <0.01), and more frequently received cART > 6 months prior to inclusion (98% vs. 83.1%, p < 0.05).

In terms of demographic characteristics, participants with a HADS+ were less likely to have paid employment (29.2% vs. 51%, P < 0.001) ().

Participants with a HADS+ had a lower median social support score (62.5 vs. 79.7, P < 0.001), higher median internalized HIV-related stigma score (17 vs. 14, P < 0.001), lower median treatment adherence self-efficacy score (99 vs. 109, P < 0.001), lower median physical quality of life score (46.0 vs. 53.8, P0.001), and a lower median mental quality of life score (35.9 vs. 53.6, P < 0.001) ().

A total of 259 patients who completed the HADS were defined as cART experienced. Detectable HIV-RNA was found in 12.6% of the participants with a HADS+ compared to 9.3% in the HADS− group. (P0.41). Participants with a HADS+ were more likely to be self-reported non-adherent to cART (71.3% vs. 43.6%, ) (OR = 3.17; 95%CI: 1.82–5.52).

Internal consistency

The HADS Cronbach’s α for anxiety was 0.79, for depression 0.76, and for the total HADS 0.87 ().

Table 2. Summary statistics of the HADS-A, HADS-D, and HADS-T.

CIDI in MLWH

The CIDI was administered to 67/106 (63%) participants with a HADS+ (). However, in six participants the time between the HADS and the CIDI was more than three months while the HADS was not repeated. These participants were excluded from analyses. Of the remaining 61 participants, the HADS was repeated in 58. All participants had a HADS+ during the first assessment and 24/61 (39%) were found to have a HADS− in the second HADS. Differences in HADS scores ranged from 1 to 21.

In all 61 patients with either HADS+ or HADS− more than 3 months after the initial HADS+ (second assessment), the CIDI was performed (). The CIDI was partially or fully completed by 60/61. Of the participants with a HADS+, 21/37 (57%) had a diagnosis of depression or anxiety disorder based on the CIDI and 4/23 (17%) of the participants with a HADS− were diagnosed with a depressive or anxiety disorder based on the CIDI as well (P < 0.01).

Table 3. Association between HADS and CIDI.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed whether the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) can be used in standard of care of MLWH to measure psychological distress. The results demonstrated that the HADS can be easily administered in MLWH from different origins. In addition, we assessed the association between psychological distress and treatment adherence to cART. This association was found, indicating that the HADS may be a valuable addition in clinical care for MLWH. When symptoms of psychological distress have been determined, HIV care providers need to be aware about the risk of non-adherence to treatment.

One-third of the MLWH had a HADS score of ≥15 (HADS+), indicating psychological distress. This percentage is in line with studies in non-migrant PLWH (Ibbotson et al., Citation1994; Kugaya et al., Citation2000). In addition, participants with a HADS+ less often received paid employment and were on sick leave more often compared to participants with a HADS−. A recent study showed that entering paid employment for ≥12 hours per week resulted in better mental health in people with mental health problems (Schuring, Robroek, & Burdorf, Citation2017). These results indicate that supporting patients with mental health problems in starting (part time) jobs with paid employment might improve their mental health status. However, it is possible that participants experienced psychological distress due to losing paid employment or being unable to work due to psychological distress. Future research should take the reasons for unemployment into account to determine appropriate interventions. Furthermore, worse results on psychosocial outcomes (like higher internalized HIV-related stigma, less experienced social support, less treatment adherence self-efficacy, and lower quality of life) were found in participants with a HADS+ compared to participants with a HADS−. These results are in line with previous studies on the association between symptoms of psychological distress and various psychosocial outcomes in patients with chronical illness (Betancur, Lins, Oliveira, & Brites, Citation2017; Eller et al., Citation2014; Rendina, Millar, & Parsons, Citation2018; Wu et al., Citation2013). In line with a meta-analysis (Uthman et al., Citation2014), our data indicate that participants with a HADS+ were more likely to be non-adherent to cART.

The HADS showed good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s α of 0.87 for the HADS-T, 0.79 for the HADS-A, and 0.76 for the HADS-D. The results from the subscales are slightly lower than the α’s in a study where 747 papers were reviewed (Bjelland et al., Citation2002). Mean α’s of 0.83 for the HADS-A 0.83 and 0.82 for the HADS-D were reported. The α of the HADS-T is in line with the α reported in a validation study of the HADS in different Dutch populations, which ranged from 0.82 to 0.90 (Spinhoven et al., Citation1997). In addition, in 21/37 (57%) a diagnosis of depression or anxiety disorder based on the CIDI and 4/23 (17%) of the participants with a HADS− were diagnosed with a depressive or anxiety disorder based on the CIDI as well (P < 0.01). However, the HADS seemed to be only a snapshot of the participants’ symptoms of psychological distress since the score changed from a HADS+ to a HADS− in 39% of the participants that were retested after a more than 3 month time period. Previous studies have shown variable test-retest reliability scores ranging from 0.91 for the HADS-T with a maximum of three weeks between administrations, 0.46 and 0.43 for the HADS-A and HADS-D with a maximum of 90 days between administrations (McPherson & Martin, Citation2011; Spinhoven et al., Citation1997). However, lower scores have been found with less time between the tests as well (McPherson & Martin, Citation2011). Therefore, results from the HADS should not be seen as a given for a longer period of time. It should be repeated, even after several weeks have passed.

A strength of our study was that the HADS was completed by 87% (306/352) in a multicultural, multilingual population. Therefore, it has shown that the use of this screening tool in a difficult to reach and diagnose population is possible based on the use of translated versions of the HADS. However, as the language may not be a large problem in cross cultural study populations, the interpretation of the resulted may be. Maters, Sanderman, Kim, and Coyne (Citation2013) reported that very few validation studies report about challenges in cross-cultural use of the HADS (Maters et al., Citation2013). Additionally, several interviewers reported participants having difficulties in interpreting some of the questions, e.g., the interpretation of the phrase “butterflies in the stomach”. Therefore, validations studies of translations of the HADS should always take the cultural background of its participants into consideration. Lastly, we found that a large proportion of the participants (78%) completed the HADS in Dutch. This might be explained by the fact that about 30% of the participants originate from former Dutch colonies in the Caribbean and Surinam where Dutch is (one of the) main language(s). In addition, about 90% of the participants have lived in the Netherlands for ≥5 years at the time of inclusion.

A possible limitation of our study is that although 106 participants were eligible to complete the CIDI, the administration of the CIDI proved to be challenging in this population. The CIDI was initiated in 61 (57.5%) and completed by 60. In this study, it was possible to administer the CIDI in Dutch and English. Licenses for translations in French and Spanish were not available, which excluded several participants from the CIDI. In addition, a large proportion of the participants that did not initiate the CIDI 32/39 (82%) refused to participate, could not be reached to make an appointment, or did not show up at their appointment. Furthermore, when the CIDI was started, the time spend to complete the CIDI varied between 15 minutes to several hours and language barriers were common reasons for the delay in completion. Another limitation is that the properties of the CIDI as a diagnostic test were based on the results of the participants with an initial a HADS+. The ideal procedure would have been to have offered the CIDI to participants with an initial HADS− as well. However, we believe that this would not have been feasible because of the expected additional burden (time investment) for the 200 participants. A final limitation might be that by using the HADS-T to determine symptoms of psychological distress, some participants who had a higher score on only one of the two subscales may have been “missed”. Previous studies have used cut-off scores of ≥8 or ≥11 for the individual subscales (Bjelland et al., Citation2002). In our study, 33 participants had a HADS-A or HADS-D score of ≥8 and did not have a HADS-T of ≥15 and four participants had a HADS-A or HADS-D score of ≥11 and did not have a HADS-T of ≥15.

In conclusion, in a large group of MLWH in the Netherlands, more than 34% were at risk for psychological distress (HADS+). In 57% of the participants, a HADS+ indicated a diagnosis of depression or anxiety disorder based on the CIDI. However, the HADS score seems to be only a snapshot of symptoms of psychological distress and should be repeated after several weeks. In MLWH, screening for symptoms of anxiety and depression should be part of their treatment given the association with self-reported non-adherence. The HADS seems to be suitable for MPLWH from different cultural backgrounds. When administering the HADS and interpreting its results, the cultural background of its participants should be taken into consideration.

Study registration number

Netherlands Trial Registry Number (NTR) – NTR4941.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, S.K. Been, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating patients for their time and willingness to contribute to this study. We also thank the physicians and nurses at Erasmus University Medical Center and Maasstad Hospital, and the members of the interview team, for their efforts. This work was supported by an unrestricted scientific grant by the Dutch Aids Fonds.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

S.K. Been http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5755-3306

Additional information

Funding

References

- Been, S. K., van de Vijver, D. A., Nieuwkerk, P. T., Brito, I., Stutterheim, S. E., Bos, A. E., … Verbon, A. (2016). Risk factors for non-adherence to cART in immigrants with HIV living in the Netherlands: Results from the ROtterdam ADherence (ROAD) project. PLoS One, 11(10), e0162800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162800

- Betancur, M. N., Lins, L., Oliveira, I. R., & Brites, C. (2017). Quality of life, anxiety and depression in patients with HIV/AIDS who present poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A cross-sectional study in Salvador, Brazil. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 21(5), 507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2017.04.004

- Bhugra, D., Gupta, S., Schouler-Ocak, M., Graeff-Calliess, I., Deakin, N. A., Qureshi, A., … European Psychiatric, A. (2014). EPA guidance mental health care of migrants. European Psychiatry, 29(2), 107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.01.003

- Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T., & Neckelmann, D. (2002). The validity of the Hospital anxiety and depression Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52(2), 69–77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3

- Booth, B. M., Kirchner, J. E., Hamilton, G., Harrell, R., & Smith, G. R. (1998). Diagnosing depression in the medically ill: Validity of a lay-administered structured diagnostic interview. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 32(6), 353–360. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3956(98)00031-4

- Brandt, C., Zvolensky, M. J., Woods, S. P., Gonzalez, A., Safren, S. A., & O’Cleirigh, C. M. (2017). Anxiety symptoms and disorders among adults living with HIV and AIDS: A critical review and integrative synthesis of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 164–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.11.005

- Campos, L. N., Guimaraes, M. D., & Remien, R. H. (2010). Anxiety and depression symptoms as risk factors for non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Brazil. Aids and Behavior, 14(2), 289–299. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9435-8

- de Wit, M. A., Tuinebreijer, W. C., Dekker, J., Beekman, A. J., Gorissen, W. H., Schrier, A. C., … Verhoeff, A. P. (2008). Depressive and anxiety disorders in different ethnic groups. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(11), 905–912. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0382-5

- Eller, L. S., Rivero-Mendez, M., Voss, J., Chen, W. T., Chaiphibalsarisdi, P., Iipinge, S., … Brion, J. M. (2014). Depressive symptoms, self-esteem, HIV symptom management self-efficacy and self-compassion in people living with HIV. AIDS Care, 26(7), 795–803. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.841842

- Feuillet, P., Lert, F., Tron, L., Aubriere, C., Spire, B., Dray-Spira, R., & Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le Sida et les Hepatites Virales, V. I. H. E. s. l. p. a. S. G. (2017). Prevalence of and factors associated with depression among people living with HIV in France. HIV Medicine, 18(6), 383–394. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12438

- Gonzalez, J. S., Batchelder, A. W., Psaros, C., & Safren, S. A. (2011). Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: A review and meta-analysis. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 58(2), 181–187. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0B013E31822D490A

- Herrmann, C. (1997). International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – A review of validation data and clinical results. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 42(1), 17–41. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00216-4

- Ibbotson, T., Maguire, P., Selby, P., Priestman, T., & Wallace, L. (1994). Screening for anxiety and depression in cancer patients: The effects of disease and treatment. European Journal of Cancer, 30(1), 37–40. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(05)80015-2

- Johnson, M. O., Neilands, T. B., Dilworth, S. E., Morin, S. F., Remien, R. H., & Chesney, M. A. (2007). The role of self-efficacy in HIV treatment adherence: Validation of the HIV Treatment Adherence Self-efficacy Scale (HIV-ASES). Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30(5), 359–370. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9118-3

- Kalichman, S. C., Simbayi, L. C., Cloete, A., Mthembu, P. P., Mkhonta, R. N., & Ginindza, T. (2009). Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: The Internalized AIDS-related Stigma Scale. AIDS Care, 21(1), 87–93. doi:906575058 [pii] 10.1080/09540120802032627

- Kugaya, A., Akechi, T., Okuyama, T., Nakano, T., Mikami, I., Okamura, H., & Uchitomi, Y. (2000). Prevalence, predictive factors, and screening for psychologic distress in patients with newly diagnosed head and neck cancer. Cancer, 88(12), 2817–2823. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000615)88:12<2817::AID-CNCR22>3.0.CO;2-N

- Langebeek, N., Gisolf, E. H., Reiss, P., Vervoort, S. C., Hafsteinsdottir, T. B., Richter, C., … Nieuwkerk, P. T. (2014). Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: A meta-analysis. BMC Medicine, 12(142).

- Maters, G. A., Sanderman, R., Kim, A. Y., & Coyne, J. C. (2013). Problems in cross-cultural use of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: “no butterflies in the desert”. PLoS One, 8(8), e70975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070975

- May, M. T., Gompels, M., Delpech, V., Porter, K., Orkin, C., Kegg, S., … Study, U. K. C. H. C. (2014). Impact on life expectancy of HIV-1 positive individuals of CD4+ cell count and viral load response to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS (London, England), 28(8), 1193–1202. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000243

- McPherson, A., & Martin, C. R. (2011). Is the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) an appropriate screening tool for use in an alcohol-dependent population? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(11–12), 1507–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03514.x

- Michigan, U. o. (2017). The World Health Organization World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WHO WMH-CIDI). Retrieved from https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmhcidi/

- Monge, S., Alejos, B., Dronda, F., Del Romero, J., Iribarren, J. A., Pulido, F., … CoRis. (2013). Inequalities in HIV disease management and progression in migrants from Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa living in Spain. HIV Medicine, 14(5), 273–283. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12001

- Moser, A., Stuck, A. E., Silliman, R. A., Ganz, P. A., & Clough-Gorr, K. M. (2012). The eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey: Psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 65(10), 1107–1116. doi:S0895-4356(12)00116-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.04.007

- Nellen, J. F. J. B., Nieuwkerk, P. T., Burger, D. M., Wibaut, M., Gras, L. A., & Prins, J. M. (2009). Which method of adherence measurement is most suitable for daily use to predict virological failure among immigrant and non-immigrant HIV-1 infected patients? Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/Hiv, 21(7), 842–850. doi: 10.1080/09540120802612816

- Penninx, B. W., Beekman, A. T., Smit, J. H., Zitman, F. G., Nolen, W. A., Spinhoven, P., … Consortium, N. R. (2008). The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA): Rationale, objectives and methods. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 17(3), 121–140. doi: 10.1002/mpr.256

- Rendina, H. J., Millar, B. M., & Parsons, J. T. (2018). The critical role of internalized HIV-related stigma in the daily negative affective experiences of HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.005

- Robertson, K., Bayon, C., Molina, J. M., McNamara, P., Resch, C., Munoz-Moreno, J. A., … van Wyk, J. (2014). Screening for neurocognitive impairment, depression, and anxiety in HIV-infected patients in Western Europe and Canada. AIDS Care, 26(12), 1555–1561. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.936813

- Robins, L. N., Wing, J., Wittchen, H. U., Helzer, J. E., Babor, T. F., Burke, J., … Regier, D. A. (1988). The composite international diagnostic interview. Archives of General Psychiatry, 45(12), 1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003

- Roth, A. J., Kornblith, A. B., Batel-Copel, L., Peabody, E., Scher, H. I., & Holland, J. C. (1998). Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma. Cancer, 82(10), 1904–1908. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1904::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-X

- Schuring, M., Robroek, S. J., & Burdorf, A. (2017). The benefits of paid employment among persons with common mental health problems: Evidence for the selection and causation mechanism. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment & Health, 43(6), 540–549.

- Shacham, E., Nurutdinova, D., Satyanarayana, V., Stamm, K., & Overton, E. T. (2009). Routine screening for depression: Identifying a challenge for successful HIV care. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23(11), 949–955. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0064

- Spinhoven, P., Ormel, J., Sloekers, P. P., Kempen, G. I., Speckens, A. E., & Van Hemert, A. M. (1997). A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychological Medicine, 27(2), 363–370. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004382

- Staehelin, C., Keiser, O., Calmy, A., Weber, R., Elzi, L., Cavassini, M., … Swiss, H. I. V. C. S. (2012). Longer term clinical and virological outcome of sub-Saharan African participants on antiretroviral treatment in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 59(1), 79–85. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318236be70

- Stern, A. (2014). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Occupational Medicine, 64, 393–394. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu024

- Sumari-de Boer, I. M., Sprangers, M. A., Prins, J. M., & Nieuwkerk, P. T. (2012). HIV stigma and depressive symptoms are related to adherence and virological response to antiretroviral treatment among immigrant and indigenous HIV infected patients. AIDS and Behavior, 16(6), 1681–1689. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0112-y

- Todd, J. V., Cole, S. R., Pence, B. W., Lesko, C. R., Bacchetti, P., Cohen, M. H., … Adimora, A. A. (2017). Effects of antiretroviral therapy and depressive symptoms on all-cause mortality among HIV-infected women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 185(10), 869–878. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww192

- Trickey, A., May, M. T., Vehreschild, J.-J., Obel, N., Gill, M. J., Crane, H. M., … Sterne, J. A. C. 2017. Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: A collaborative analysis of cohort studies. The Lancet HIV, 4(8), e349–e356. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3018(17)30066-8

- Uthman, O. A., Magidson, J. F., Safren, S. A., & Nachega, J. B. (2014). Depression and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low-, middle- and high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 11(3), 291–307. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0220-1

- Van Sighem, A., Gras, L., K, A., Smit, C. E., Stolte, E., & Reiss, I. (2013). Monitoring Report 2013: Humaan Immunodeficiancy Virus (HIV) Infection in the Netherlands. Retrieved from Amsterdam, The Netherlands. https://www.hiv-monitoring.nl/application/files/7715/3312/9974/SHM_MonitoringReport2013.pdf

- Ware Jr., J., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S. D. (1996). A 12-item short-Form health Survey. Medical Care, 34(3), 220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003

- WHO. (2017, n.a.). The World Health Organization World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WHO WMH-CIDI). Retrieved from https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmhcidi/

- Wu, S. F., Young, L. S., Yeh, F. C., Jian, Y. M., Cheng, K. C., & Lee, M. C. (2013). Correlations among social support, depression, and anxiety in patients with type-2 diabetes. Journal of Nursing Research, 21(2), 129–138. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0b013e3182921fe1

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x