ABSTRACT

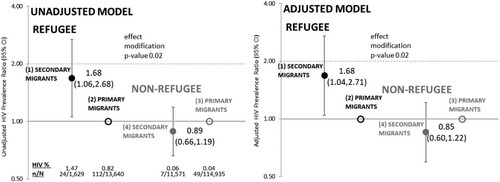

Forced migration and extended time spent migrating may lead to prolonged marginalization and increased risk of HIV. We conducted a population-based cohort study to examine whether secondary migration status, where secondary migrants resided in a transition country prior to arrival in Ontario, Canada and primary migrants arrived directly from their country of birth, modified the relationship between refugee status and HIV. Unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios (APR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using log-binomial regression. In sensitivity analysis, refugees with secondary migration were matched to the other three groups on country of birth, age and year of arrival (+/− 5 years) and analyzed using conditional logistic regression. Unmatched and matched models were adjusted for age and education. HIV prevalence among secondary and primary refugees and non-refugees was 1.47% (24/1629), 0.82% (112/13,640), 0.06% (7/11,571) and 0.04% (49/114,935), respectively. Secondary migration was a significant effect modifier (p-value = .02). Refugees with secondary migration were 68% more likely to have HIV than refugees with primary migration (PR = 1.68, 95% CI 1.06, 2.68; APR = 1.68, 95% 1.04, 2.71) with a stronger effect in the matched model. There was no difference among non-refugee immigrants. Secondary migration may amplify HIV risk among refugee but not non-refugee immigrant mothers.

Introduction

Research finds that the social, economic and political deprivation leading to migration can affect both risk factors for HIV exposure (i.e., number of partners) and factors that mediate infection (i.e., condom availability) (Haour-Knipe, de Zalduondo, Samuels, Molesworth, & Sehgal, Citation2014). Since refugees (also known as “forced migrants”), often experience extreme forms of marginalization, it is thought that they are particularly vulnerable to HIV (UNAIDS, Citation2007). A Dutch study found that asylum-seekers were 20 times more likely to have HIV compared to non-Western immigrants (Van Hanegem, Miltenburg, Zwart, Bloemenkamp, & Van Roosmalen, Citation2011). Prior to 2018 (Government of Canada, Citation2018), Canadian immigration policy allowed refugees, but not the majority of non-refugee immigrants, with HIV to be admitted on humanitarian grounds (Government of Canada, Citation2017). Consequently refugee mothers in Canada were 8 and 17 times more likely to have HIV compared to non-refugee immigrant and Canadian-born mothers, respectively (Wanigaratne et al., Citation2015). A study more directly controlling for country of birth demonstated that refugee mothers in Canada were twice as likely to have HIV compared to non-refugee mothers (Wanigaratne et al., Citation2018).

However, for refugees who initially seek asylum in a transition country before coming to Canada, a lack of adequate formal and/or informal social protection available in these countries (Long & Sabates-Wheeler, Citation2017) can contribute to similar or worse social circumstances than in their home countries and increased risk of contracting HIV. Specifically, this can occur if HIV prevalence is higher in a transition community (i.e., the community of initial asylum) compared to the refugee’s community, and if high-risk sexual interaction takes place between the two communities (Spiegel, Citation2004; UNAIDS, Citation2014). In such circumstances, high-risk interaction may result from increased sexual violence or forced sex work (Haour-Knipe et al., Citation2014; Spiegel, Citation2004). Given these possible circumstances in transition countries, HIV risk may be higher among those refugees who reside in such countries prior to arriving in Canada (i.e., secondary migrant) compared to refugees who arrive directly to Canada (i.e., primary migrant).

Voluntary migrants residing in a transition country before coming to Canada may also lack social protection; particulary if they are unskilled and employed in unregulated jobs with poor pay and no health benefits (Long & Sabates-Wheeler, Citation2017), also putting them at increased risk for sexual exploitation in transition countries (Haour-Knipe et al., Citation2014). For both refugees and some voluntary migrants, residence in a transition country may be an indicator for prolonged marginalization and higher HIV risk (Haour-Knipe et al., Citation2014).

Using official Canadian immigration data, this study examined whether the relationship between HIV prevalence and refugee status was modified by secondary migration status. To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the effect of the combination of refugee status and secondary migration status on the prevalence of HIV among immigrants in a high-income country.

Methods

Population-based administrative databases were linked through encoded unique identifiers assigned to individuals eligible for universal healthcare coverage, and analyzed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences in Toronto, Ontario.

The Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada Permanent Resident Database (IRCC-PRD) contains official immigration records for individuals who received permanent residency in Canada (2002–2012) and is valid and complete (Chiu et al., Citation2016). Refugee and secondary migration status, country of birth (COB), refugee sponsorship status, country of last permanent residence (i.e., transit country), arrival year, and education at arrival were determined using the IRCC-PRD. The definition of a refugee was that used by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) – forced to flee because of persecution, war or violence; persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a social group. The comparator to refugees was economic and family class immigrants (i.e., voluntary migrants or non-refugees). Secondary migrants were those who resided in an intermediate/transit country for at least 6 months prior to arriving in Canada, as opposed to primary migrants who arrived to Canada directly from their COB. COB and last permanent residence were categorized using the UN regional classification system (United Nations Statistics Division, Citation2013).

In Ontario, HIV testing and counseling is widely available (Queen’s Printer for Ontario, Citation2019) but is only routinely offered to pregnant women. Between 2002 and 2010 the proportion of pregnant women in Ontario tested for HIV went up from 77% to 98% (Remis et al., Citation2012). Given the almost complete HIV testing coverage for pregnant women, we chose to focus our analyses on this sub-population of refugee and non-refugee immigrant rather than all refugee and non-refugee immigrants. Linkage between the Ontario HIV Database (1992–2014) and the The Canadian Institute for Health Information’s Discharge Abstract Database (2002–2014) was used to identify all mothers diagnosed with HIV prior todelivery in an Ontario hospital. An HIV diagnosis was based on three physician claims for an HIV diagnosis within 3 years (Antoniou, Zagorski, Loutfy, Strike, & Glazier, Citation2011) and all analyses were restricted to the first birth recorded in the hospitalization database for mothers aged 15–50 years old.

As a part of the descriptive analyses, HIV prevalence for refugees with primary and secondary migration were further stratified by sponsorship status since non-sponsored refugees (i.e., refugee claimants or asylum-seekers) lack formal support prior to immigration to Canada and may be more vulnerable to HIV exposure compared to sponsored refugees who are supported by the UNHCR prior to arrival.

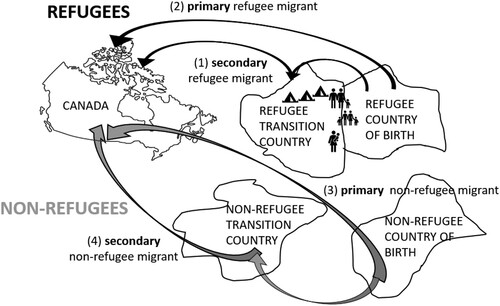

Multivariate log-binomial regression was used to estimate unadjusted (PR) and adjusted prevalence ratios (APR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The main effect was refugee status (refugee immigrant vs. non-refugee immigrant) and the effect modifier of interest was secondary migration status (secondary vs. primary migrant). Please see for an illustration describing the interaction of the main effect and effect modifier (groups specified here are numbered similarly in ). A p-value < .05 on the interaction term between refugee status and secondary migration status indicated that secondary migration status significantly modified the relationship between refugee status and HIV prevalence. Given that global HIV prevalence is much higher in specific countries (e.g., in Sub Saharan Africa) we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) to take into account the potential non-independence of HIV among mothers from the same country of birth. Models were adjusted for education at arrival (0–9 years, 10–12 years, 13+ years, trade certificate/non-university diploma, University degree) and maternal age at delivery (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40+ years). Individuals with missing data were excluded from analyses. Parity, marital status at arrival, residential neighborhood income quintile at birth were determined not to be confounders of the relationship between refugee status and HIV prevalence.

Figure 1. Illustrating the interaction of refugee status (i.e., the main effect) with secondary migration status (i.e., the effect modifier) examined in this study. Primary refugee migrants arrive to Canada directly from their country of birth (often a country experiencing conflict/instability – group 1) while secondary refugee migrants typically reside in a neighboring transition country for a period of time prior to arriving in Canada (group 1). Primary non-refugee migrants arrive to Canada directly from their country of birth (group 3) while secondary non-refugee immigrants typically transition through a non-neighboring country (group 4) before arriving in Canada.

Figure 2. Unadjusted and adjusted HIV prevalence ratios and 95% CI for HIV in Ontario, Canada (2002–2014), according to refugee status (refugee vs. non-refugee immigrant) and stratified by secondary migration status (secondary vs. primary migrant). Note: Used generalized estimating equations to take into account similar HIV prevalence among mothers from the same country of birth. Adjusted for maternal age categories (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40+ years) and education at arrival categories (0–9 years, 10–12 years, 13+ years, trade certificate/non-university diploma, University degree).

To more effectively examine the potential influence of secondary migration, independent of country of birth and the calendar time and age an immigrant woman arrived to Canada, we conducted a sensitivity analysis where refugees with primary migration, non-refugees with primary migration and secondary migration were matched 1:1 to refugees with secondary migration on COB, age and year of arrival (+/− 5 years). This matched cohort was analysed using conditional logistic regression to take into account matching between secondary refugees and the other three groups. The main effect, effect modifier and confounders were the same as in the unmatched model described previously. Prevalence odds ratios (POR) and adjusted PORs (APOR) with 95% CI were estimated.

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and the research ethics board at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Canada (#13-289).

Results

Characteristics of the study population are summarized in . For non-refugees with primary (N = 114,935) and secondary migration (N = 11,571), HIV prevalence was 0.04% and 0.06%, respectively. HIV prevalence among refugees with primary (N = 13,640) and secondary (N = 1629) migration were higher, 0.82% and 1.47%, respectively. HIV prevalence was higher among non-sponsored compared to sponsored refugees (secondary migrants: 1.92% vs. 1.39%, respectively; primary migrants: 1.16% vs. 0.79%, respectively). Mothers born in Sub Saharan Africa constituted the largest group among all refugees (26%). Secondary refugees were more likely to transit through an intermediate country in the same region as their COB than their non-refugee counterparts, who mostly transited through Western and Central Asia/North Africa or Developed countries (data not shown).

Table 1 . Characteristics of first live births in Ontario (2002–2014) to refugees and non-refugees with secondary and primary migration (arriving to Ontario, 2002–2012). Percent of column (%) and count (n).

In unadjusted and adjusted regression analyses (), secondary migration status significantly modified the relationship between HIV prevalence and refugee status (p = .02). Refugees with secondary migration were 68% more likely to have HIV compared to refugees with primary migration (APR = 1.68, 95% CI 1.04, 2.71; PR = 1.68, 95% CI 1.06, 2.68), while HIV prevalence was similar for non-refugees with secondary and primary migration (APR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.60, 1.22; PR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.66, 1.19).

In the matched unadjusted and adjusted models (n = 1175 in each group), refugee status was also found to significantly modify the relationship between HIV prevalence and secondary migration status (p = .03 and p = .02, respectively). These results suggested similar findings to our main analysis however both estimates were non-significant; the POR for refugees with secondary migration compared to refugees with primary migration was 2.11 (95% CI 0.92, 4.86) and the APOR was 2.39 (95% CI 0.88, 6.48), while the POR for non-refugees with secondary migration compared to non-refugees with primary migration was 0.15 (95% CI 0.02, 1.31) and the APOR was 0.10 (95% CI 0.01, 1.19).

Discussion

We found that the relationship between refugee status and HIV prevalence was significantly modified by secondary migration status. Refugee mothers who resided in a transition country after leaving their country of birth but before arriving in Canada were twice as likely to have HIV compared to refugee mothers who arrived in Canada directly from their country of birth. However, we found no difference in HIV prevalence between non-refugee immigrant mothers who resided in a transition country and those who came directly to Canada. These findings were similar to a model where country of birth, age and year of migration were more directly controlled for (i.e., through matching of refugees with secondary migration to the three other groups).

These findings occur against a backdrop of Canadian immigration policy which permitted refugees to overcome health-based exclusion policies more often than other immigrants for humanitarian reasons (Wanigaratne et al., Citation2015) which likely explains the higher HIV prevalence among refugees compared to non-refugee immigrant mothers in this study. However, there is no known policy which permits even greater numbers of HIV+ refugees with secondary migration. These findings suggest social, economic and political marginalization experienced during secondary migration may increase refugee women’s risk of contracting HIV. Refugees who reside in transition countries before coming to Canada may face additional challenges and be exposed to these challenges for longer periods of time than refugees who arrive directly to Canada. Deteriorating social structures and inadequate security may have led to sexual violence; and precarious legal status may have caused financial vulnerability, forcing women to resort to sex work or to trade sex in order to meet basic needs (Haour-Knipe et al., Citation2014; Spiegel, Citation2004). Limited access to HIV services may have further compounded the risk (The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, Citation2016). Higher HIV prevalence among non-sponsored compared to sponsored refugees also suggests the former may be more likely to have these experiences. That we found no difference between non-refugee immigrants with secondary and primary migration likely speaks to the fact that the majority of Canada’s voluntary migrants are highly skilled and educated (or spousal dependents of these immigrants) and therefore less likely to be marginalized and more likely to be given or be able to afford social protections and health care in transition countries before arriving in Canada.

In a cohort of HIV positive women living in three provinces in Canada (n = 1330), legal status (i.e., permanent residents, asylum-seekers and Canadian citizen) was significantly associated with acquiring HIV through forced vs. consensual sex (p < .001) (Logie et al., Citation2017). Permanent residents (n = 120) and asylum seekers (i.e., refugees who are not yet permanent residents) (n = 42) had more than two (adjusted OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.12, 3.54) and almost four (adjusted OR 3.62, 95% CI 1.63, 8.04) times greater odds, respectively, of aqcuiring HIV through forced sex compared to their Canadian citizen counterparts (n = 715) (Logie et al., Citation2017). This suggests that forced sex is an important factor in HIV acquisition among refugees with primary migration and a likely even stronger factor among refugees with secondary migration given the much higher prevalence of HIV. Logie et al. (Citation2017) also found that women who acquired HIV through forced sex had 3 times greater odds of having a history of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared to women who acquired HIV through consensual sex (adjusted OR 3.00, 95% CI 1.68, 5.38). Since the history of PTSD could not be accurately captured in the administrative data used in this study, we were not able to examine this. However, given the potential that HIV was acquired through forced sex combined with the association with PTSD, health care professionals should pay special to the mental health needs of HIV + refugee women with primary, and particularly secondary migration to ensure access to appropriate counseling.

It is also important that health care providers are sensitive to the intersecting forms of stigma and discrimination particular groups of HIV+ women face in Canada when seeking out and receiving treatment, care and support for HIV. Approximately 80% of HIV+ immigrant women in our study were born in African or Carribean countries. The Canadian HIV/AIDS Black, African & Caribbean Network describes a continuum of health services that are required for a person living with HIV to achieve optimal health, starting from HIV testing and diagnosis to support while on anti-retroviral therapy (Canadian HIV/AIDS Black, African & Caribbean Network, Citationn.d.a). HIV-related stigma (Loutfy et al., Citation2012) and discrimination, uncertainty around immigration status and anti-black racism in the health care system are all barriers to achieving optimal health for those living with HIV which disproportionately affect women from African and Caribbean countries (Canadian HIV/AIDS Black, African & Caribbean Network, Citationn.d.b). There are numerous ways that health service providers can help overcome these barriers; such as helping to address the social determinants of health which prevents access to care and providing or linking individuals to HIV care that is comprehensive, respectful and sensitive (Canadian HIV/AIDS Black, African & Caribbean Network, Citationn.d.c).

Our study has limitations. We did not have information on where HIV was contracted, however it is likely that HIV was contracted abroad since: HIV+ refugees are more likely to be admitted to Canada than other immigrants (as per immigration policy); 85% of refugees were diagnosed with HIV in Ontario within 6 months of becoming a permanent resident; and analyses were restricted to the first birth in Canada. We had no data describing the pre-migration experiences of refugees which may shed light on what circumstances confer greater risk for HIV among refugees with secondary migration. However, sensitivity analyses matching on COB, age and year of arrival allowed us to create a reasonable counterfactual for secondary refugees, suggesting that between two refugee women with similar risk of HIV, the chances of contracting HIV doubles for the refugee who is forced to reside in a transition country prior to coming to Canada. We acknowledge that this sensitivity analysis was underpowered, which likely explains why the prevalence ratio approached, but did not reach, statistical significance. None-the-less, in both unmatched and matched models, the effect size was large (∼2) and relevant to public health. We also estimated that 44% of HIV infections among refugees with secondary migration could be attributed to residing in a transition country before arriving in Canada.

Conclusions

Secondary migration is an important determinant of health for refugee women – we found HIV prevalence was almost twice as high if a refugee resided in a transit country prior to arriving in Canada. Research is needed to examine whether other sexually transmitted infections show a similar pattern. In Canada, guidelines recommend HIV screening of immigrants if they were born in a country where HIV prevalence is ≥1% (Pottie et al., Citation2011). It would be beneficial to expand these screening criteria to include refugee status. Health care professionals may need to pay special attention to the mental health needs of refugees with secondary migration and should also be aware of and help overcome barriers to HIV treatment, care and support stemming from HIV-related stigma and discrimination faced by racialized women. From an international perspective, considering the numerous new and continued refugee crises worldwide, including the 800,000 Rohingya who fled Myanmar for Bangladesh (International Organization for Migration, Citation2017), we echo calls to improve reproductive health services (IAWG, Citation2016) and the financial and personal security of refugee women (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Citation2003) in conflict settings.

Disclaimer statement

The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by IC/ES or the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and information compilied and provided by CIHI. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the author, and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Antoniou, T., Zagorski, B., Loutfy, M. R., Strike, C., & Glazier, R. H. (2011). Validation of case-finding algorithms derived from administrative data for identifying adults living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection. PLoS ONE, 6(6), e21748. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021748

- Canadian HIV/AIDS Black, African & Caribbean Network. (n.d.a). HIV stigma in African, Caribbean and Black communities. Retrieved from http://www.icad-cisd.com/pdf/CHABAC/Publications-Presentations/CHABAC_Stigma-fact-sheet_FINAL_EN.pdf

- Canadian HIV/AIDS Black, African & Caribbean Network. (n.d.b). INFO SHEET #1: The HIV engagement cascade and African, Caribbean & Black communities. Retrieved from http://www.icad-cisd.com/pdf/CHABAC/Info-Sheet-1-HIV-Engagement-Cascade-ACB-Communities-EN.pdf

- Canadian HIV/AIDS Black, African & Caribbean Network. (n.d.c). INFO SHEET #2: Interventions along the HIV engagement cascade for African, Caribbean & Black communities. Retrieved from http://www.icad-cisd.com/pdf/CHABAC/Info-Sheet-2-HIV-Engagement-Cascade-ACB-Communities-EN.pdf

- Chiu, M., Lebenbaum, M., Lam, K., Chong, N., Azimaee, M., Iron, K., … Guttmann, A. (2016). Describing the linkages of the immigration, refugees and citizenship Canada permanent resident data and vital statistics death registry to Ontario’s administrative health database. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 16(1). doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0375-3

- Government of Canada. (2017, August 23). Procedure for HIV-positive cases. Retrieved December 21, 2017, from https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/publications-manuals/operational-bulletins-manuals/standard-requirements/medical-requirements/surveillance-notifications/procedure-hiv-positive-cases.html

- Government of Canada. (2018, December 21). Excessive demand: Calculation of the cost threshold, 2018. Retrieved April 14, 2019, from https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/publications-manuals/excessive-demand.html

- Haour-Knipe, M., de Zalduondo, B., Samuels, F., Molesworth, K., & Sehgal, S. (2014). HIV and “people on the Move”: Six Strategies to Reduce risk and vulnerability during the migration Process. International Migration, 52(4), 9–25. doi: 10.1111/imig.12063

- IAWG. (2016). Interagency working group on Reproductive Health in crises. Retrieved December 14, 2016, from http://iawg.net/

- International Organization for Migration. (2017, October 27). Two months on from outbreak of violence, number of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh reaches 817,000. Retrieved from https://www.iom.int/news/two-months-outbreak-violence-number-rohingya-refugees-bangladesh-reaches-817000

- Logie, C. H., Kaida, A., de Pokomandy, A., O’Brien, N., O’Campo, P., MacGillivray, J., … Jabbari, S. (2017). Prevalence and correlates of forced sex as a self-reported mode of HIV acquisition among a cohort of women living with HIV in Canada. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi: 10.1177/0886260517718832

- Long, K., & Sabates-Wheeler, R. (2017). Migration, forced displacement and social protection [GSDRC Rapid Literature Review]. Retrieved from University of Birmingham website: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=2ahUKEwi0mpeG_d7cAhUJo4MKHf6EAzMQFjAAegQIABAC&url=http://www.gsdrc.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2017%2F06%2FMigration-Forced-Displacement-and-Social-Protection-2017-06-20-BL.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0ZLUzywGsyJTYn-N4GWi9w

- Loutfy, M. R., Logie, C. H., Zhang, Y., Blitz, S. L., Margolese, S. L., Tharao, W. E., … Raboud, J. M. (2012). Gender and ethnicity differences in HIV-related stigma experienced by people living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE, 7(12), e48168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048168

- Pottie, K., Greenaway, C., Feightner, J., Welch, V., Swinkels, H., Rashid, M., … coauthors of the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health. (2011). Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de L’Association Medicale Canadienne, 183(12), E824–E925. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090313

- Queen’s Printer for Ontario. (2019, March 25). HIV/AIDS tests and treatment. Retrieved April 14, 2019, from http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/hivaids/hiv_testing.aspx

- Remis, R. S., Merid, M. F., Palmer, R. W. H., Whittingham, E., King, S. M., Danson, N. S., … Major, C. (2012). High uptake of HIV testing in pregnant women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE, 7(11), e48077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048077

- Spiegel, P. B. (2004). HIV/AIDS among conflict-affected and displaced populations: Dispelling myths and taking action. Disasters, 28(3), 322–339. doi: 10.1111/j.0361-3666.2004.00261.x

- The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. (2016). 2014-2015 UBRAF thematic report. Addressing HIV in humanitarian emergencies. Retrieved from https://results.unaids.org/sites/default/files/documents/Addressing_HIV_in_humanitarian_emergencies_Jun2016.pdf

- UNAIDS. (2007, February 23). HIV and refugees. Retrieved September 1, 2017, from http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2007/february/20070223hivandrefugees

- UNAIDS. (2014). The Gap Report. Retrieved from UNAIDS website: http://files.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2003). Sexual and gender-based violence against refugees, returnees and internally displaced persons – Guidelines for prevention and response. Retrieved from United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees website: https://www.unicef.org/emerg/files/gl_sgbv03.pdf

- United Nations Statistics Division. (2013, October 31). Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groups. Retrieved from http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm

- Van Hanegem, N., Miltenburg, A. S., Zwart, J. J., Bloemenkamp, K. W. M., & Van Roosmalen, J. (2011). Severe acute maternal morbidity in asylum seekers: A two-year nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 90(9), 1010–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01140.x

- Wanigaratne, S., Cole, D. C., Bassil, K., Hyman, I., Moineddin, R., & Urquia, M. L. (2015). Contribution of HIV to maternal morbidity among refugee women in Canada. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), 2449–2456. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302886

- Wanigaratne, S., Shakya, Y., Gagnon, A. J., Cole, D. C., Rashid, M., Blake, J., & Uquia, M. L. (2018). Refugee maternal and perinatal health in Ontario, Canada: A retrospective population-based study. BMJ Open, 8(4), e108979. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018979