ABSTRACT

To increase linkage to and retention in antiretroviral therapy (ART) care, we piloted a community-based, ART service delivery intervention for female sex workers (FSWs). At baseline, we recruited and collected data from 617 FSWs (intervention: 309; comparison: 308) who were HIV positive and not on ART. This paper presents (1) the description of the intervention model, and (2) key descriptive and bivariate-level findings of the baseline FSW cohort. The data showed more than half of FSWs had a non-paying sex partner, and less than one-third used a condom at last sex with paying and non-paying clients, which suggest potentially high levels of HIV transmission. In addition, there is a gap in HIV testing and treatment because one-third learned about their HIV-positive status only at study enrollment, and among FSWs who had known their status for more than a month, half had not registered in care. This substantiates the importance of timely HIV diagnosis and treatment. A community-based ART program may serve as an important strategy in closing the HIV care and treatment gap for FSWs.

Introduction

In Tanzania, the HIV prevalence among FSWs (28%) is about 4.5 times that of the general female population. (Kerrigan et al., Citation2017; Vu & Misra, Citation2017). A systematic review of ART uptake among HIV-positive FSWs, globally, estimated ART initiation at 36%; adherence at 76%; and viral suppression at 57% (Mountain et al., Citation2014). Meeting the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets requires programs and policies to look beyond HIV testing and counseling (HTC) in health facilities and consider approaches at all levels. A systematic review found that various populations – including FSWs – reached through community-based HTC had high rates of uptake and linkages to care and achieved high CD4 counts and viral suppression (Sharma, Ying, Tarr, & Barnabas, Citation2015). To make ART more accessible, acceptable, and effective for highly stigmatized populations, WHO recommends: clinical services located near places of sex work; flexible clinic hours; emergency drug pick-ups; patient-held records for those who may seek ART at different sites; and non-judgmental staff attitudes (WHO, Citation2016).

The Sauti project – a 5-year USAID-funded key population program led by Jhpiego – is providing HIV care and ART through clinicians in community-based HIV testing and counseling (CBHTC) mobile and home-based settings for FSWs in Tanzania. This paper presents the intervention model and implementation science research on the key descriptive and bivariate-level findings of the baseline FSW cohort.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a quasi-experimental prospective cohort study to examine differences in treatment outcomes between intervention and comparison sites, which entailed a baseline behavioral survey and 6- and 12-month follow-ups. The Population Council Institutional Review Board and the National Institute for Medical Research (Tanzania) approved the study. All participants provided written informed consent.

Study sites

The Njombe (intervention) and Mbeya (comparison) regions were selected as study sites. Njombe was selected because of its high HIV burden and status as a priority region for the donor, and Mbeya was selected due to its high HIV prevalence and because Sauti was operating its CBHTC program in the region similar to Njombe. Additionally, both regions are part of the “Southern Highlands transportation corridor” – a major trucking route – and host many mobile seasonal workers, making the sites ripe for a large sex work community.

Description of the intervention

The intervention was designed to facilitate ART initiation and retention by reducing barriers to ART access, including stigma, discrimination, long distance travel, and costs to clients for monthly clinic visits. It was also built upon the existing CBHTC Sauti model, which provides HTC, STI screening and treatment, referrals of HIV positive clients, condom distribution, family planning, referrals for cases of violence, tuberculosis screening, and cervical cancer screening for key populations.

ART delivery in intervention region

At intervention enrollment, FSWs received ART adherence counseling and a one-month supply of anti-retroviral drugs (ARVs) following the government of Tanzania’s test and start policy. After the first month, participants were given a 2-month ARV supply. Subsequently, stable participants were given a 3-month supply of ARVs per visit. “The CBHTC team included at least one nurse who had 2 years of general clinical training plus recent training in ART delivery, a lab technician, and several peer educators.”

Services offered in comparison region

FSWs were referred to public facilities for ART services, where they received a monthly supply of ARVs. FSWs were also eligible to receive all services offered by the Sauti project, as described above.

Study population

Women aged 18 and above, selling sex for money or goods at least once in the past 6 months, HIV positive and not currently on ART, and planning to reside in Njombe or Mbeya for the next 12 months were eligible. We estimated a sample size for detecting a difference of 20 percentage points in retention and viral suppression outcomes. The final sample size was estimated as 300 per region.

Baseline cohort recruitment and data collection

From July–August 2017, we recruited study participants by: (1) conducting community-based HTC in hotspots; and (2) contacting FSWs who were previously diagnosed through Sauti HTC services but not yet on treatment. Additionally, Sauti attracted FSWs to the study using brochures, health facility announcements, peer support groups, and HIV counseling sessions. If interested, FSWs returned to the CBHTC site for screening and enrollment.

The baseline survey covered demographics, HIV-related risk behaviors, HIV testing history, health status, sexual abuse, self-stigma (for those who had been diagnosed HIV-positive for at least a month), and ART enrollment (for those who have known their positive status for at least a month). HIV self-stigma was measured using a validated 6-item scale assessing participants’ feelings of shame and guilt from living with HIV (Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, Citation2001).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were analyzed using Stata Software (Version 14.1, College Station, Texas). Baseline characteristics, HIV-related risk, and linkages to HIV care of the study population in the two sites were compared using Chi-square and t-tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Results

presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the study population at baseline. Participants in the comparison group were slightly older (median: 32 vs. 29) and less educated (secondary education or more: 7% vs. 20%) compared to intervention group.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population in the intervention and comparison regions (N = 617).

About half of the participants were never married and a third (34%) were divorced, widowed, or separated. Most participants (83%) reported having at least one living child. Over one-third reported that more than half of their income came from sex work in the past six months. Over one-third of FSWs (35%) in the intervention group reported traveling out of the region to sell sex in the past six months, which was significantly higher than the comparison group (10%).

describes HIV-related characteristics of participants in the two sites. The median age FSWs started selling sex was 20 years. Those in the intervention were significantly more likely to report having more than one non-paying sex partner in the past month compared to the comparison group (32% vs. 12%). Most participants in both groups reported not using a condom during their last sexual intercourse with a paying client (59%) and a non-paying sex partner (75%). Among participants diagnosed with HIV for more than a month, 60% did not disclose their status to a sex partner. Nearly one-fifth (19%) of FSWs were drunk during their last sexual encounter with a paying client. A similar proportion of FSWs (20%) reported being sexually abused (raped, forced, or threatened to have sex) at least once in the past 6 months.

Table 2. HIV vulnerability and related characteristics of participants in the intervention and comparison regions (N = 617).

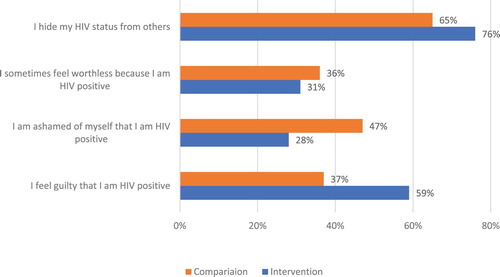

shows high levels of self-stigma, such as feeling worthless because of living with HIV (77% in intervention and 67% in comparison) or feeling guilty because of having HIV (59% and 38%, respectively), and nearly one-third felt ashamed living with HIV (28% and 47%, respectively).

Figure 1. Self-stigma (N = 97; those who have known their HIV-positive status for at least a month).

presents HIV testing history, STI testing uptake, and enrollment in care at baseline. The intervention region had a significantly lower proportion of participants who were diagnosed as HIV-positive the day they were interviewed (18% vs. 45%).

Table 3. HIV testing, STI testing uptake, and enrollment in HIV care and treatment among participants in the intervention and comparison regions.

Among those who knew of their status for more than a month, a significantly higher proportion in the intervention had been registered in HIV care than the comparison (72% vs. 50%). The main reasons for not registering were that they felt healthy (53%) and feared stigma (27%). Those in the comparison group were significantly more likely to have had an STI checkup than the intervention (40% vs. 20%).

Discussion

To improve ART outcomes among FSWs, we designed and are piloting an innovative, community-based ART delivery model built on an existing community-based mobile HTC platform. This ART model is the first to be implemented among FSWs in Tanzania combining both aspects of service integration and decentralization (bringing services to the community level and incorporating treatment into testing services). This could reduce barriers in accessing care and increase linkage to and retention in care and viral suppression. We recruited a cohort of 617 FSWs not on ART into the study. Initial baseline findings suggest there are gaps in reaching the 90-90-90 targets. This is illustrated by the fact that one-third of FSWs were diagnosed on the date of the survey, suggesting many participants are first time testers, recently infected, or unaware of their positive status.

Among those who knew their positive diagnosis for at least a month, only 41% had registered in HIV care, demonstrating a gap in access to care and treatment services. The findings that nearly half of FSWs had a non-paying sex partner and only about one-third used a condom at last sex with paying and non-paying clients are of concern, considering the significant prevention efforts targeting FSWs in Tanzania and the free distribution of condoms to FSWs for more than a decade through major social marketing initiatives (Sweat, Denison, Kennedy, Tedrow, & O'Reilly, Citation2012). Combined with the lack of awareness of HIV status, low condom use could potentially escalate HIV transmission to the general population, as FSWs play a critical role in HIV transmission (Chen et al., Citation2007; Côté et al., Citation2004; Lowndes et al., Citation2003). This further supports the importance of early HIV treatment and the potential impact of the community-based ART model.

Baseline data also demonstrates a high prevalence of sexual violence, which has been found to undermine HIV prevention efforts and increase FSW vulnerability to HIV transmission (Decker et al., Citation2015; Nyblade, Stangl, Weiss, & Ashburn, Citation2009). The continuation of Sauti’s interventions, such as sex-worker education on rights, community mobilization to respond to violence, and policy advocacy to promote human rights of sex workers are critical (Moore et al., Citation2014; Weller & Davis-Beaty, Citation2002). Furthermore, nearly one-fifth of participants reported being drunk at last sex with a client. High levels of drinking coupled with misinformation has be shown to negatively affect ART adherence (Lancaster et al., Citation2017; Mbonye, Rutakumwa, Weiss, & Seeley, Citation2014).

The finding that under one-third of FSWs had an STI checkup during the past 3 months and nearly 21% were told by a doctor that they had syphilis or gonorrhea is in line with the most recent IBBS data that over 10% had active syphilis, suggesting the need for periodic presumptive treatment of curable STIs, as recommended by WHO (Kaul et al., Citation2004; Kaul et al., Citation2007). Internalized stigma was also high, which is consistent with past research and indicates the need for stigma reduction interventions (Cornish, Citation2006; Donastorg, Barrington, Perez, & Kerrigan, Citation2014; Logie, James, Tharao, & Loutfy, Citation2011). Evidence indicates that empowerment programs, education on rights, and provider training can help mitigate external and internal stigma (Aggleton, Wood, Malcolm, & Parker, Citation2005; Kerrigan et al., Citation2015; Nyblade et al., Citation2009).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, most outcomes were self-reported, including HIV testing history and key risk factors. Many risk factors may be underestimated due to participant reluctance to report sex work. Second, finding a suitable comparison group proved difficult since the intervention site was selected for being the region with the highest burden of HIV. Baseline data showed that participants are not comparable on several factors, including condom use, violence, stigma, and STI testing. We will investigate how these differences affect key outcomes and perform adjustments during midline and end-line data analyses.

Conclusions

Findings from the baseline data showed gaps in reaching the HIV care and treatment targets, and a potentially high level of HIV transmission from FSWs to their paying clients and non-paying sexual partners. National HIV responses should expand their strategies to effectively identify HIV-positive FSWs and provide them with ART services immediately upon HIV diagnosis. A community-based ART program like the Sauti CBHTC model being tested may serve as an important strategy in closing these gaps.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to specially thank Hally Mahler (FHI360) for her contribution to the development of the study concept, and Albert Komba (Jhpiego) for his contribution to the study concept and strong support during implementation. This study would not have been possible without the NIMR research team, including John Changalucha, Catherine Bunga, Erick Mgina, and Charles Mangya. We greatly appreciate the work of our Jhpiego colleagues who assisted with the implementation of the ART model, and all the nurses, counselors, peer educators and study participants.LV and WT conceived the research design. LV, WT, CC, NM, EM conceived the intervention design (ART model). CC, LA, LV and WT refined the intervention design. LV and WT conducted data analysis and drafted the manuscript. LA oversaw fieldwork and managed M&E data. LA and DM monitored data collection. CC drafted the intervention description. ST contributed to literature review and drafted the introduction and result. All authors provided critical review and comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aggleton, P., Wood, K., Malcolm, A., & Parker, R. (2005). HIV-related stigma discrimination and human rights violations: case studies of successful programmes.

- Berger, B. E., Ferrans, C. E., & Lashley, F. R. (2001). Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing & Health, 24(6), 518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011

- Chen, L., Jha, P., Stirling, B., Sgaier, S. K., Daid, T., Kaul, R., … Investigators, I. S. o. H. A. (2007). Sexual risk factors for HIV infection in early and advanced HIV epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic overview of 68 epidemiological studies. PLoS One, 2(10), e1001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001001

- Cornish, F. (2006). Challenging the stigma of sex work in India: Material context and symbolic change. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 16(6), 462–471. doi: 10.1002/casp.894

- Côté, A.-M., Sobela, F., Dzokoto, A., Nzambi, K., Asamoah-Adu, C., Labbé, A.-C., … Pépin, J. (2004). Transactional sex is the driving force in the dynamics of HIV in Accra, Ghana. Aids (london, England), 18(6), 917–925. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200404090-00009

- Decker, M. R., Crago, A. L., Chu, S. K., Sherman, S. G., Seshu, M. S., Buthelezi, K., … Beyrer, C. (2015). Human rights violations against sex workers: Burden and effect on HIV. Lancet, 385(9963), 186–199. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60800-X

- Donastorg, Y., Barrington, C., Perez, M., & Kerrigan, D. (2014). Abriendo Puertas: Baseline findings from an integrated intervention to promote prevention, treatment and care among FSW living with HIV in the Dominican Republic. PLoS One, 9(2), e88157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088157

- Kaul, R., Kimani, J., Nagelkerke, N. J., Fonck, K., Ngugi, E. N., Keli, F., … Kibera, H. I. V. S. G. (2004). Monthly antibiotic chemoprophylaxis and incidence of sexually transmitted infections and HIV-1 infection in Kenyan sex workers: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 291(21), 2555–2562. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2555

- Kaul, R., Nagelkerke, N. J., Kimani, J., Ngugi, E., Bwayo, J. J., Macdonald, K. S., … Kibera, H. I. V. S. G. (2007). Prevalent herpes simplex virus type 2 infection is associated with altered vaginal flora and an increased susceptibility to multiple sexually transmitted infections. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 196(11), 1692–1697. doi: 10.1086/522006

- Kerrigan, D., Kennedy, C. E., Morgan-Thomas, R., Reza-Paul, S., Mwangi, P., Win, K. T., … Butler, J. (2015). A community empowerment approach to the HIV response among sex workers: Effectiveness, challenges, and considerations for implementation and scale-up. The Lancet, 385(9963), 172–185. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60973-9

- Kerrigan, D., Mbwambo, J., Likindikoki, S., Beckham, S., Mwampashi, A., Shembilu, C., … Galai, N. (2017). Project Shikamana: Baseline findings from a community empowerment–based Combination HIV prevention trial among female sex workers in Iringa, Tanzania. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 74(Suppl 1), S60. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001203

- Lancaster, K. E., Lungu, T., Mmodzi, P., Hosseinipour, M. C., Chadwick, K., Powers, K. A., … Miller, W. C. (2017). The association between substance use and sub-optimal HIV treatment engagement among HIV-infected female sex workers in Lilongwe, Malawi. AIDS Care, 29(2), 197–203. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1211244

- Logie, C. H., James, L., Tharao, W., & Loutfy, M. R. (2011). HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work: A qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Medicine, 8(11), e1001124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001124

- Lowndes, C., Alary, M., Labbe, A., Gnintoungbe, C., Belleau, M., & Mukenge-Tshibaka, L. (2003). Male clients of female sex workers in Cotonou, Benin (West Africa): contribution to the HIV epidemic and effect of targeted interventions. Paper presented at the 15th Biennial Congress of the International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research, Ottawa.

- Mbonye, M., Rutakumwa, R., Weiss, H., & Seeley, J. (2014). Alcohol consumption and high risk sexual behaviour among female sex workers in Uganda. African Journal of AIDS Research, 13(2), 145–151. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2014.927779

- Moore, L., Chersich, M. F., Steen, R., Reza-Paul, S., Dhana, A., Vuylsteke, B., … Scorgie, F. (2014). Community empowerment and involvement of female sex workers in targeted sexual and reproductive health interventions in Africa: A systematic review. Globalization and Health, 10, 47. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-10-47

- Mountain, E., Mishra, S., Vickerman, P., Pickles, M., Gilks, C., & Boily, M.-C. (2014). Antiretroviral therapy uptake, attrition, adherence and outcomes among HIV-infected female sex workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 9(9), e105645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105645

- Nyblade, L., Stangl, A., Weiss, E., & Ashburn, K. (2009). Combating HIV stigma in health care settings: What works? Journal of the International AIDS Society, 12(1), 15. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-15

- Sharma, M., Ying, R., Tarr, G., & Barnabas, R. (2015). Systematic review and meta-analysis of community and facility-based HIV testing to address linkage to care gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature, 528(7580), S77–S85. doi: 10.1038/nature16044

- Sweat, M. D., Denison, J., Kennedy, C., Tedrow, V., & O'Reilly, K. (2012). Effects of condom social marketing on condom use in developing countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis, 1990-2010. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(8), 613–622. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.094268

- Vu, L., & Misra, K. (2017). High burden of HIV, syphilis and HSV-2 and factors associated with HIV infection among female sex workers in Tanzania: Implications for early treatment of HIV and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). AIDS and Behavior, Apr;22(4):1113–1121. doi:10.1007/s10461-017-1992-2

- Weller, S. C., & Davis-Beaty, K. (2002). Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. The Cochrane Library, Cochrane Database Syst Rev., 2002;(1):CD003255.

- WHO. (2016). Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Recommendations for a public health approach - 2nd ed.