ABSTRACT

Young perinatally-infected women living with HIV in Zambia grew up alongside antiretroviral therapy (ART) roll-out and expanding prevention programmes. We used Bonnington’s temporal framework to understand how HIV impacted the experiences of these women over time. Data were drawn from two sequential studies with a cohort of young women living with HIV: a qualitative study in 2014–16 and an ethnographic study in 2017–18. Data from workshops, in-depth interviews, participant observation and diaries were analysed thematically, guided by three temporalities within the framework: everyday, biographical and epochal time. In everyday time, repetitive daily treatment-taking reminded young women of their HIV status, affecting relationships and leading to secrecy with ART. In biographical time, past events including HIV disclosure, experiences of illness, and loss shaped present experiences and future aspirations. Lastly, in epochal time, the women’s HIV infection and their survival were intimately interlinked with the history of ART availability. The epochal temporal understanding leads us to extend Reynolds Whyte’s notion of “biogeneration” to conceptualise these women, whose experiences of living with HIV are enmeshed with their biosocial environment. Support groups for young women living with HIV should help them to process biographical events, as well as supporting their everyday needs.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Young people living with HIV are viewed as a focal population in the HIV response (World Health Organization, Citation2018). However, our understandings of their lives are often drawn from cross-sectional studies or research with limited follow-up periods (Salam, Das, Lassi, & Bhutta, Citation2016). This is despite adolescence being characterised as a period of ongoing physical, cognitive, emotional, and social changes (Patton et al., Citation2016). A deeper understanding of their experiences over time as they grow up with HIV is needed to ensure that interventions are well targeted to young people as they develop.

In Zambia, where an estimated 65,000 young people (aged 15–24) are living with HIV (UNICEF, Citation2019), the epidemic has “touched the lives of all Zambians” (Simpson & Bond, Citation2014, p. 1067). HIV was first identified in Zambia in the 1980s, and by the 1990s the epidemic had escalated, leaving the country grappling with affected families, HIV care, and education programming in the absence of effective treatment (Simpson & Bond, Citation2014). In 2004, antiretroviral therapy (ART) became available in public health facilities, enabling transformations for some people living with HIV from ill-health to relative wellness (Simpson & Bond, Citation2014). Those who were saved by the introduction of ART have been described as constituting a “biogeneration”, due to their shared relationship to ART when this biotechnology became widely accessible (Reynolds Whyte, Citation2014, p. 11).

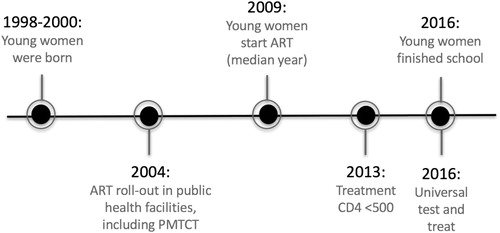

Young people currently aged 15–24 years were born in the period where HIV had escalated, but before widespread availability of treatment. They grew up through changing HIV policies and treatment availability (). These include the national policy change to using ART to prevent mother-to-child transmission from 2004 (World Health Organization, Citation2004), expanding treatment availability to CD4 counts below 500 after World Health Organization recommendations in 2013 (World Health Organization, Citation2013), and universal test and treat in 2016 (National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council, Citation2016). Young people’s lived experiences of growing up with HIV are intertwined with this shifting context as it changes over time.

Figure 1. Timeline of the developments of the young women in the study, mapped against changes in HIV treatment policy in Zambia.

Although time is an “inescapable dimension of all aspects of social experience and practice” (Munn, Citation1992, p. 93), HIV experiences have often been understood within a singular view of time (eg. Before or after testing, or after an intervention), rather than one where overlapping temporalities affect the contexts and concerns of people living with HIV (Bonnington et al., Citation2017). Illness can cause a “biographical disruption”, radically disrupting one’s day-to-day arrangements and understandings of oneself, and one’s past, present and future (Bury, Citation1982). Bonnington’s concept of overlapping temporalities – everyday, biographical and epochal time – was used to examine the manifestation of stigma for people living with HIV at stages of the HIV care continuum (Bonnington et al., Citation2017). Although a growing body of research has looked at the experience of health and disease through a temporal lens (Beynon-Jones, Citation2017; Golander, Citation1995; Reddy, Dourish, & Pratt, Citation2006; Seeley, Citation2015), few researchers have considered the experiences of young people living with HIV in terms of their past and present lives, in the particular era within which they were born.

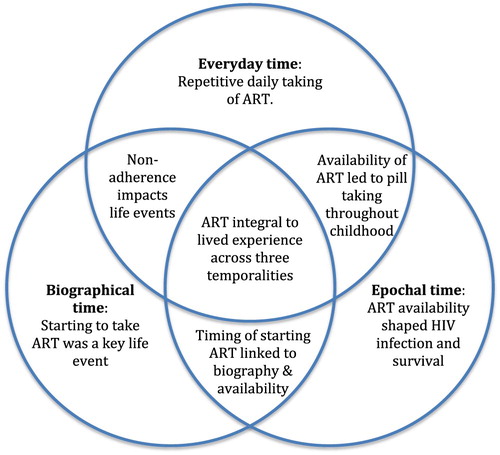

In this paper, we use Bonnington’s temporal framework (Citation2017) to understand the impact of HIV on the experiences of young women living with HIV through three temporalities: everyday, biographical and epochal. In this analysis, everyday time involves the immediacy and repetition of daily experiences of HIV. Biographical time concerns the link between past, present and future events and processes related to HIV. Lastly, epochal time encapsulates the historical shifts, including how global, national and local developments in responses to the HIV epidemic, including treatment availability, influenced the experiences of this generation of young Zambian women living with HIV.

Methods

This analysis draws on two sequential studies: a qualitative study and an ethnographic study, both undertaken with young women living with HIV in Lusaka, Zambia. The qualitative study ran from 2014 to 2015 with 24 young women living with HIV aged 15–18 years, and aimed to understand the challenges they faced and their support needs. Participants were recruited from two health facilities (), and data collection included four participatory workshops and 34 in-depth interviews (IDI). Details of the methods used for this study have been presented elsewhere (Mackworth-Young et al., Citation2017). In 2015-16, after the close of the study, support groups were established at each health facility, and were held monthly over a period of a year; in total 20 meetings were held.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

In 2017-18, middle-income young women from this qualitative research study were purposefully selected and asked to participate in an ethnographic study. The selection criterion of being middle-income was principally chosen because, although middle-income populations are rapidly growing in Zambia and have a high HIV prevalence in Zambia (Central Statistical Office & MoH., Citation2014), they have been under-represented in research (Long & Deane, Citation2015). Additionally, the middle-income young women spoke English, which enabled the researcher to conduct the ethnographic study without the need for a translator. The seven young women who consented to participate were then aged 17–19 years (). Data were generated through participant observation over 12 months in participants’ homes, workplaces, colleges, recreational spaces, health facilities and churches in dozens of locations across Lusaka. The research began and ended with participatory workshops to gather their experiences collectively and receive their input into the research design and analysis. The introductory workshop included discussions with participants to gather their input into the research design, focus and objectives, and establish how best to present the research to others. Discussions also included participants’ views and preferences with regards to different research methods, for example choice of methods for keeping diaries. The closing workshop included discussing initial results with the participants, and undertaking participatory activities to develop and refine some key findings. Additionally, participants created visual collages to represent themselves, and wrote in diaries about their activities, experiences and feelings. Details of the data collection of the ethnographic study have been presented elsewhere (Mackworth-Young et al., Citation2019).

Data from the two studies were analysed together, focusing on the sub-group of young women who participated in the ethnography (the second study). In conducting analysis, attention was paid to the longitudinal nature of the data and changes to participants’ lives over the four years during which data were collected. Workshop notes, IDI transcripts, notes from support group meetings, participant observation notes, transcripts of the diaries and the visual collages were manually coded analysed using Bonnington’s temporality framework (2017). Sub-themes emerged inductively, and data on each sub-theme were collated and analysed together. For example, under biographical time, the sub-themes included HIV’s impact on past, present and future moments: i) HIV disclosure; ii) experiences of illness and loss; and iii) future aspirations.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Zambia Humanities Research Ethics Committee, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the International Centre for Research on Women. Ethical issues that emerged have been discussed separately (Mackworth-Young et al., Citation2019).

Findings

HIV experiences in everyday time

HIV impacted the young women in everyday time through repetitive daily experiences. The daily act of taking ART was the clearest reminder of HIV in their lives. While the young women were able to follow the daily routine of treatment-taking, it protected their health and largely prevented any bodily signs of HIV. This allowed the young women to “feel comfortable”, “look healthy” (Rhoda, participant observation, 2016) and to enjoy everyday activities with their peers, including going to school and college, shopping, studying, and daily chores. However, it was often an unwelcome reminder of HIV in their lives:

I didn’t like having to take them every day, every day being reminded that I have this thing. (Rose, participant observation, 2016)

HIV also impacted the young women’s daily experiences through the effect on their friendships and their familial and sexual relationships. For close family and friends who knew their HIV status, this shared knowledge of their HIV status fostered a closeness and support, “filled with love” (Natasha, diary, 2018). For some, this closeness was manifested daily through family and friends being protective of the young women. Sometimes this was experienced as over-protective: “My sister is always worried when I go out” (Mavis, participant observation, 2017). Knowledge of their HIV status also engendered support, including being reminded to take their medicines by close family: “Usually she reminds me: ‘have you been taking your medicine’?” (Rhoda, IDI, 2015).

However, the young women’s wider family, friends and sexual partners did not know their HIV status. This led to fears of involuntary disclosure, clouding relationships and making the daily taking of ART a social risk. The young women went to great lengths to hide their ART and the daily pill taking, with some collecting their ARVs before the allocated time and keeping it on their person to avoid anyone noticing them going to the storage place at the same time each day. To maintain relationships with family, friends and partners, the young women had to carefully plan their everyday activities, particularly those related to obtaining and taking their treatment, in order to protect their HIV status. These findings were similar for the young women regardless of mode of HIV infection.

HIV experiences in biographical time

HIV influenced the young women’s lives at key moments across their past, present and future aspirations, and in turn the past influenced present and future experiences and aspirations.

The most significant past moment when HIV impacted the young women’s lives was when they found out about their HIV status. Those who had been perinatally infected with HIV were mostly unaware of their HIV status during their childhood, and were told that they were living with HIV when they were around 10–14 years old, usually by their parent or guardian, or, for one participant, by a health professional. Many saw this as a pivotal moment that shaped their biography:

I’m kind of seeing my life changed, because I don’t have the freedom that I used to have before. (Thandi, IDI, 2015)

Even if people say things about me, or anyone could discriminate against me, it doesn't matter, because I now have so much confidence in myself. (Sophie, participant observation, 2018)

To be made an orphan, a double orphan, is really worrying. Who would look after me?. (Mary, participant observation, 2017)

My father died, then my mother two years later. I still remember my mother in hospital. I don’t really talk about it. It’s so hard, but I will manage. I just have to do the best for my young sisters. (Sophie, participant observation, 2017)

I would want to go to school and study, either Clinical Medicine, Nursing or Midwifery. I pray that I get a scholarship from any sponsoring organisation. (Rhoda, diary, 2018)

HIV experiences in epochal time

HIV influenced the young women’s experience within the biosocial epoch in which they grew up. All but one of the participants were born with HIV. For those perinatally infected with HIV, both their HIV infection and their survival to adulthood were intimately interlinked with the socio-historical availability of ART. They largely understood that they had been infected in this way because their mothers had not had access to, or had not taken ART, during pregnancy. Most of their mothers would not have known their HIV status at the time, their pregnancies being prior to the introduction of routine antenatal HIV testing.

And did your mother also have HIV?

Yes. (pause) And she told me I contracted the virus from her.

Ok. And did she have more children after you?

Yes, she’s got two … Both are girls.

Both are girls. And do you know if they have HIV?

No, they are not. She was taking medicines when she was pregnant with them. Since I think they now always do that for the women who are HIV positive. (Sophie, IDI, 2015)

So how am I supposed to take this if my brother isn’t positive and I am?. (Thandi, IDI, 2015)

But when time goes on you pass by it, you see, it’s not like your life will be different (because of your status). It will be just the same. (Thandi, participant observation, 2018)

Most people who are on treatment are successful on treatment, just like those who are healthy. (Thandi, workshop, 2015)

Interlinking across temporalities

The experiences of the young women were not distinct within each temporality but were enmeshed and overlapping, as exemplified by their experiences around ART (). The historical availability of ART changed their experience of HIV from one of illness to survival:

I was feeling weak, and I started losing blood, everything was just bad. They took me to hospital … That’s when I started taking my medicine … And that changed my life. (Thandi, IDI, 2015)

The availability for the young women to start treatment during their childhood not only shaped their biography, but also their daily experiences. Further, the daily pill-taking, when disrupted, could impact major biographical moments and processes, such as their education:

My mum always asks “Are you managing to take them (ARVs) every day?” I always say yes because if I ever say no, mum will stop me from going to college. (Mary, participant observation, 2018)

Discussion

Through the lens of everyday, biographical and epochal time, we provide an understanding of the impact of HIV on this generation of young women. We provide evidence that their experiences go beyond the social management of day-to-day pill-taking, to the impacts of past disclosure, illness and death on their current lives and future familial aspirations, bounded by the time in which they were born and now live. As noted by Bonnington et al. (Citation2017), these temporalities interlinked, as the young women’s daily experiences influenced experiences in biographical and epochal time. For instance, daily adherence to ART could threaten not only young people’s relationships (Bernays, Paparini, Seeley, & Rhodes, Citation2017), but also valued aspects of their biographical lives, such as college attendance for these middle-income young women. “Disruptive events” (Bury, Citation1982) such as HIV disclosure impacted the young women’s biography, emotionally and socially. The impact changed over time, through increased self-confidence, and even over-confidence for some that they felt they were healthy enough to stop taking their daily ART.

The young women who were perinatally infected with HIV recognised that they were born at a very particular time in history, where ART was not yet widely available to prevent mother-to-child transmission, but was available during their childhood, which enabled them to survive. We build on Reynolds Whyte’s term “biogeneration”, which she uses to describe the previous generation of adults who were expected to die from AIDS in the 1990s and survived due to medical intervention in the early 2000s (Reynolds Whyte, Citation2014). We here expand it to refer to this generation of young people perinatally infected with HIV. For the young women in this study who were perinatally infected, both their HIV infection and their survival are fundamentally interlinked with the historical, social, political and biomedical environment. This links to Foucauldian notions of biopolitics, of how the bodies of young women living with HIV are themselves the site of biomedicine and politics (Foucault, Citation1997). If further connects to Fassin’s exploration of the impact of politics on individual’s bodies, deeply situated in the social history of the South African HIV epidemic (Fassin, Citation2007). This research builds on Fassin’s work to demonstrate how the impact of HIV on young women is necessarily placed in the context of local and global politics. Their bodies, their illness and their health are inextricably tied to their close family histories as well as wider bio-medical developments. By viewing young women living with HIV as a particular “biogeneration”, we acknowledge their lives and HIV infection to be deeply situated in political bio-medical and social history, including ART availability and family history of HIV infection.

As optimum interventions are being developed to support this “biogeneration” of young people living with HIV (for example, Cluver et al., Citation2018; Graves et al., Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2017; Mavhu et al., Citation2017), our data aid understanding of their experiences, providing valuable evidence as to how to provide comprehensive support. Increasingly support groups are being established to support young people living with HIV (Bateganya, Amanyeiwe, Roxo, & Dong, Citation2015; Cowan et al., Citation2019; Mavhu et al., Citation2017). However, some have been critiqued for focusing too heavily on adherence, with little room for discussion about other critical topics including the multitude of challenges they face related to HIV and more broadly, or openness about the practical and emotional challenges and strategies to manage daily adherence (Bernays et al., Citation2017; Bernays, Paparini, Gibb, & Seeley, Citation2016). Our findings suggest that support for young women living with HIV should acknowledge the fundamental biographical moments that have shaped, or will shape, their lives, including illness, death, learning about their HIV status, and decision-making around having children. Including topics such as “loss and grief” and “disclosure” in support group curriculums has been shown to be effective at enabling young people living with HIV to process challenging moments in their biography together with others who have had similar experiences (Clay et al., Citation2018; Stangl et al., Citation2018). Further, discussing future aspirations that these middle-income young women held, including around education and employment, supports them to consider future opportunities regardless of their HIV status. Providing information on treatment as prevention and PMTCT is key to ameliorate fears about having healthy families in the future, and support aspirations of young women living with HIV to have children (Bernays et al., Citation2019; Clay et al., Citation2018).

Temporal analyses provide a breadth of understanding of young women’s experiences of HIV, beyond one snapshot in time. By means of analysis through epochal time, we suggest reframing this cohort as a specific “biogeneration”: a generation whose lives and experience of HIV is intimately interlinked to the history of ART availability in Zambia. We thereby understand some of their experiences as being particular to their generation, and our response to support them should be targeted and adaptive as this cohort grows up with HIV. We recommend support groups with a focus on collectively talking about significant biographical challenges as well as day-to-day issues that young women living with HIV face within this specific epochal time, to provide holistic support for them now and as they grow up with HIV.

Acknowledgements

Primarily we would like to thank the young women who participated in the studies for sharing their stories, time and lives with us. We also thank the clinic staff and volunteers who assisted with the initial recruitment of participants. Many thanks to Katongo Konumya, Sue Clay, Chipo Chiiya, and Mwangala Mwale who were involved in the data collection and workshop facilitation. We are grateful to Rokaya Ginwalla and Mohammed Limbada for providing advice on the history of HIV and ART in Zambia. Many thanks to Peter Godfrey-Faussett for kindly reading a draft of the manuscript and for his comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bateganya, M. H., Amanyeiwe, U., Roxo, U., & Dong, M. (2015). Impact of support groups for people living with HIV on clinical outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 68(Suppl 3), S368–S374. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000000519

- Bernays, S., Paparini, S., Gibb, D., & Seeley, J. (2016). When information does not suffice: Young people living with HIV and communication about ART adherence in the clinic. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 11(1), 60–68. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2015.1128581

- Bernays, S., Paparini, S., Seeley, J., & Rhodes, T. (2017). ‘Not taking it will just be like a Sin': Young people living with HIV and the stigmatization of less-than-perfect adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Medical Anthropology, doi: 10.1080/01459740.2017.1306856

- Bernays, S., Tshuma, M., Mvududu, K., Chikeya, A., Willis, N., Cowan, F., & Mahvu, W. (2019). Scaling the mountain: what it takes to achieve an undetectable viral load for adolescents living with HIV. Qualitative findings from the Zvandiri trial. Paper presented at the AIDS Impact, London, UK.

- Beynon-Jones, S. M. (2017). Gestating times: Women's accounts of the temporalities of pregnancies that end in abortion in England. Sociology of Health and Illness, 39(6), 832–846. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12522

- Bonnington, O., Wamoyi, J., Ddaaki, W., Bukenya, D., Ondenge, K., Skovdal, M., … Wringe, A. (2017). Changing forms of HIV-related stigma along the HIV care and treatment continuum in sub-Saharan Africa: A temporal analysis. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 93(3). doi:10.1136/sextrans-2016-052975.

- Bury, M. (1982). Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociology of Health and Illness, 4(2), 167–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939

- Central Statistical Office, & MoH. (2014). Zambia demographic and health survey 2013–14. Retrieved from Rockville, Maryland, USA: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr304/fr304.pdf

- Clay, S., Chonta, M., Chiiya, C., Mackworth-Young, C., Bond, V., & Stangl, A. (2018). Tikambisane ‘Let’s talk to each other’: a 6-session support group curriculum for adolescent girls living with HIV in Zambia. Retrieved from Washington, DC. https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/ICRW_Tikambisane_Curriculum_v7.pdf

- Cluver, L., Pantelic, M., Toska, E., Orkin, M., Casale, M., Bungane, N., & Sherr, L. (2018). STACKing the odds for adolescent survival: Health service factors associated with full retention in care and adherence amongst adolescents living with HIV in South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 21(9), e25176. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25176

- Cowan, F., Mavhu, W., Willis, N., Bernays, S., Weiss, H., Apollo, T., & Tshuma, M. (2019). Differentiated service delivery for adolescents living with HIV in Zimbabwe – the Zvandiri cluster randomized trial. Paper presented at the AIDS Impact, London, UK.

- Fassin, D. (2007). When bodies remember: Experiences and politics of AIDS in South Africa. Calnifornia, USA: University of Calnifornia Press.

- Foucault, M. (1997). The birth of biopolitics. In P. Rabinow & J. Faubion (Eds.), Ethics, subjectivity and truth (pp. 73–79). New York: New Press.

- Golander, H. (1995). Rituals of temporality: The social construction of time in a nursing ward. Journal of Aging Studies, 9(2), 119–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0890-4065(95)90007-1

- Graves, J. C., Elyanu, P., Schellack, C. J., Asire, B., Prust, M. L., Prescott, M. R., … Moberley, S. A. (2018). Impact of a family clinic day intervention on paediatric and adolescent appointment adherence and retention in antiretroviral therapy: A cluster randomized controlled trial in Uganda. PloS One, 13(3), e0192068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192068

- Li, X., Harrison, S. E., Fairchild, A. J., Chi, P., Zhao, J., & Zhao, G. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of a resilience-based intervention on psychosocial well-being of children affected by HIV/AIDS: Effects at 6- and 12-month follow-up. Social Science and Medicine, 190, 256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.007

- Long, D., & Deane, K. (2015). Wealthy and healthy? New evidence on the relationship between wealth and HIV vulnerability in Tanzania. Review of African Political Economy, 42(145), 376–393. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2015.1064817

- Mackworth-Young, CRS., Bond, V., Wringe, A., Konayuma, K., Clay, S., Chiiya, C., … Stangl, AL. (2017). “My mother told me that I should not”: A qualitative study exploring the restrictions placed on adolescent girls living with HIV in Zambia.

- Mackworth-Young, C. R.S., Schneiders, M. L., Wringe, A., Simwinga, M., & Bond, V. (2019). Navigating ‘ethics in practice’: An ethnographic case study with young women living with HIV in Zambia. Global Public Health, 14(12), 1689–1702. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1616799

- Mavhu, W., Willis, N., Mufuka, J., Mangenah, C., Mvududu, K., Bernays, S., … Cowan, F. M. (2017). Evaluating a multi-component, community-based program to improve adherence and retention in care among adolescents living with HIV in Zimbabwe: Study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials, 18(1), 478. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2198-7

- Munn, N. D. (1992). The cultural anthropology of time: A critical essay. Annual Review of Anthropology, 21, 93–123. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2155982 doi: 10.1146/annurev.an.21.100192.000521

- National HIV/AIDS/STI/TB Council. (2016). Zambia consolidated guidelines for treatment and prevention of HIV Infection. Retrieved from.

- Patton, G., Sawyer, S., Santelli, J., Ross, D., Afifi, R., Allen, N. B., … Viner, R. M. (2016). Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. The Lancet, 387(10036), 2423–2478. doi:http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1

- Reddy, M. C., Dourish, P., & Pratt, W. (2006). Temporality in medical work: Time also matters. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 15(1), 29–53. doi: 10.1007/s10606-005-9010-z

- Reynolds Whyte, S. (2014). Second chances: Surviving AIDS in Uganda. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Salam, R. A., Das, J. K., Lassi, Z. S., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016). Adolescent health interventions: Conclusions, evidence gaps, and research priorities. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(4), S88–S92. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.05.006

- Seeley, J. (2015). HIV and East Africa: 30 years in the Shadow of an epidemic. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Simpson, A., & Bond, V. (2014). Narratives of nationhood and HIV/AIDS: Reflections on multidisciplinary research on the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Zambia over the last 30 years. Journal of Southern African Studies, 40(5), Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/citedby/10.1080/03057070.2014.946222?scroll=top&needAccess=true

- Stangl, A., Mwale, M., Sebany, M., Mackworth-Young, C., Chiiya, C., Chonto, M., … Bond, V. (2018). ‘Let’s talk to each other’ (Tikambisane): the development, feasibility and acceptability of a support group intervention for adolescent girls living with HIV in Zambia. Retrieved from.

- UNICEF. (2019). Zambia country profile, HIV/ AIDS. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/zambia/hivaids

- World Health Organization. (2004). Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: Guidelines on care, treatment and support for women living with HIV/ AIDS and their children in resource-constrained settings. Retrieved from Geneva:.

- World Health Organization. (2013). Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/download/en/

- World Health Organization. (2018). WHO recommendations on adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights. Retrieved from Geneva, Switzerland: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275374/9789241514606-eng.pdf?ua=1