ABSTRACT

We investigated the feasibility and acceptability of integrating early childhood development into Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) services in Malawi.

We recruited mothers living with HIV in the PMTCT programs who had an infant ≤8 weeks of age. Group ECD sessions were delivered while mothers waited for HIV consultations. Follow up was conducted at 9 months postnatal. A sub-sample of mothers completed in-depth interviews which were translated, transcribed, and analyzed.

197 mothers were recruited for the integrated program: 147/197 (75%) enrolled, 114/147 (78%) completed follow up, and 62/114 (54%) completed interviews. Acceptability of the program was high, with reports of improved self-confidence and parenting capacity, increased father involvement and improved relationships with healthcare providers. Participants reported that the program made PMTCT visits more enjoyable and supportive, and reduced time and effort required for HIV care. Mothers also believed stigma within healthcare settings was reduced.

The integration of ECD into PMTCT is feasible and acceptable in a low-resource setting like Malawi. Findings indicate that the integration has potential to increase satisfaction and potential retention in HIV care programs. Additional research is required to test the effects of integrated programs on child health and development, maternal health and adherence.

Key messages

Benefits for mothers and children can be achieved through the successful integration of an early childhood development programme into PMTCT Option B+ services in Malawi.

Our study based on in-depth interviews with 62 mothers indicated that such an approach is feasible and acceptable.

Participating mothers reported that the integration of the early childhood development component

improved their confidence and they believed it improved their parenting;

led to improved relationships with health care providers;

increased the engagement of fathers and support from others in the family;

helped mothers build a new social network and support system through the peer engagement components;

reduced the risk of stigmatization in the health care setting.

Introduction

Integration is key to all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG3 – healthy lives and promoting wellbeing for all at all ages. While integration serves different purposes, an important aim is to ensure synergies and efficiencies in the delivery of services to achieve maximum impacts, such as for mothers and children (DiGirolamo et al., Citation2014). The 2017 Lancet Series, Advancing Early Childhood Development: From Science to Scale, suggested that the multiple contacts health services have with pregnant women, parents and families could be used successfully to support and improve early childhood development through simple but effective programmes to reinforce parenting commitment and skills (Chang et al., Citation2015; Richter et al., Citation2017). However, integration in the form of paired or packaged interventions does not inevitably improve outcomes and may not be acceptable hence the need to carefully evaluate before large-scale implementation (Briggs & Garner, Citation2006).

There is increasing interest in using HIV platforms in highly affected countries (Rochat et al., Citation2011) – in particular the prevention of vertical transmission from mother to child – in which considerable effort has been made to eliminate HIV and to simultaneously promote the development of exposed but uninfected children (Rochat, Netsi, et al., Citation2017). An integrated approach takes advantage of health contacts and has the added benefit of addressing multiple vulnerabilities for the mother and the child. First, exposed uninfected children have been found to be at higher risk for mortality and developmental challenges than non-exposed children (Powis et al., Citation2017). Second, women living with HIV who have young children have substantial needs for support with both their own challenges and those of an infant, often under resource-poor conditions (Paudel & Baral, Citation2015; Rochat, Netsi, et al., Citation2017). Third, strategies must be found to improve women’s long-term retention in HIV treatment (Gourlay et al., Citation2013), and to expand access to and use of related services, including family planning (Mkwanazi et al., Citation2015; Schwartz et al., Citation2012).

Lastly, early childhood development has been identified as the foundation of human capital across the life course, and postnatal interventions, especially for vulnerable children, are an important investment in equity (Daelmans et al., Citation2015) and have been shown to have long-term benefits in HIV prevalent regions (Rochat, Houle, Stein, Pearson, and Bland, Citation2018).

Malawi was an early adopter of PMTCT B+ (WHO, Citation2014) in 2011. B+ offers all HIV-positive pregnant and breastfeeding women with life-long ART as soon as they test positive regardless of their CD4 count or clinical disease stage (Ahmed et al., Citation2013). With a population of 18 million people, Malawi has an estimated 1 million people living with HIV and 36,000 new infections per year (UNAIDS, Citation2016). B+ in Malawi resulted in greater than 95% of pregnant women accepting testing and very high numbers of HIV-positive pregnant women on ART medication (by 2016 84% vs. 66% in 2011) (Chimbwandira et al., Citation2013; UNAIDS, Citation2016).

To sustain engagement in treatment and adherence, and to expand opportunities presented by regular contacts for B+, efforts are underway to explore the feasibility and effectiveness of the integration of related health interventions into PMTCT (Myer et al., Citation2018). In this paper, we report on a qualitative study to investigate the feasibility and acceptability of integrating an early childhood development programme into PMTCT B+ in Malawi.

Methods

The study was conducted at two large district hospitals in central Malawi (Nkhotakota and Kasungu). Both districts are primarily rural (85%), with high disease burden, and well-established Option B+ programmes.

Ethics

The study was approved by the National Health Sciences Research Committee, a Department of the Ministry of Health in Malawi (Reference: Protocol 15/11/1503).

Intervention

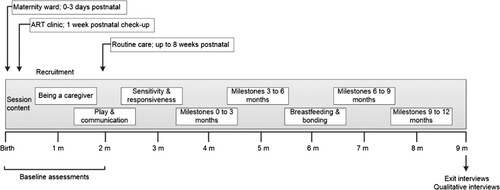

The WHO/UNICEF Care for Child Development (CCD) package has proven successful in supporting parenting, including in low-resource contexts (Lucas et al., Citation2018; Richter et al., Citation2017). Through demonstration and guidance, CCD aims to sensitise mothers to the developing cognitive, emotional and communication needs of their infants, and to reinforce caregiving sensitivity and responsivity through support and simple play activities. For example, to notice when their infant begins to reach for objects, around 3–5 months of age, and to respond by putting objects within the baby’s reach, helping them to hold the object and turning the interaction into a mutually enjoyable game. We adapted the CCD principles to local conditions and integrated it into regular HIV treatment clinic visits. Mothers on Option B+ with an infant aged 1–8 weeks were recruited after screening in antenatal, maternity and ART clinics. Enrolled mothers and their infants participated in the intervention through 45 min to 1-hour CCD group sessions held outside the ART clinic with the full cooperation of the clinic staff. Two trained lay counsellors, without prior medical or health practice experience, co-facilitated group sessions, conducting a maximum of two groups per week. The sessions also included other relevant health-related topics such as breastfeeding and bonding, nutrition for a growing child and adherence to treatment. Groups consisted of 4–10 women whose treatment visits coincided. Mothers were invited to attend 8 monthly group sessions delivered over 9 months. Each session included facilitated demonstrations and discussions about early childhood development and child milestones, time for questions, and time to observe mothers play and interact with their infants (see ).

Of 197 mother–infant pairs approached to participate in the intervention. 147 (75%) enrolled and were assigned to groups based on their monthly HIV treatment visit date. A total of 114 (78%) participants graduated the program. Attendance rate was 89%, with a range between 65% and 97%. Of these 114, 56 women completed all 8 sessions.

Follow-up interviews

A random selection of women who participated in at least six intervention sessions were invited to the health facility for a follow-up in-depth interview. Interviews were conducted immediately following graduation from the programme.

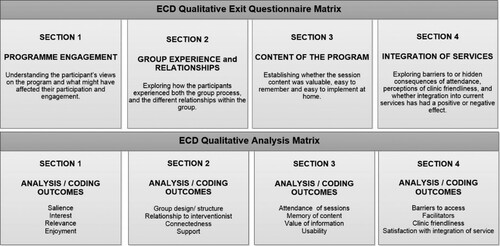

The interview guide and analysis were constructed from a conceptual matrix (). The interview guide was piloted with seven women and adjusted accordingly to achieve the aims. The final interview guide was translated into Chichewa and back-translated into English to ensure meaning equivalence.

Interviews lasted approximately 45 minutes, were tape recorded, and conducted in Chichewa by an independent research assistant. Interview data were transcribed verbatim and then translated from Chichewa into English. Transcripts and interview recordings were compared by two research assistants independently for quality assurance measures.

Two authors (SR, TR) coded transcripts using Microsoft Excel and a code book developed from the interview guide. Data were organized into matrix tables, grouping data for each question and containing the responses of all women for that specific question. The code book was designed to be exhaustive based on the frequency and the salience of the responses as well as those uncommon responses that offered a unique point of view. Data were coded using constant comparison methods (Glaser, Citation1965) through repeated readings. Codes were reviewed and discrepancies resolved. Finalized codes were systematically analysed for content.

Results

Sixty-two mothers completed an in-depth interview. presents the characteristics of women included in the analysis. The majority of mothers were married, in their 30s and with an average of 3 children. Most were Christian and almost half had not completed primary education. The category “secondary education” refers to attendance of any secondary education and not necessarily completion of secondary education. There were no educational or other differences between women who agreed to participate in the interviews and those who did not.

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

Participants found the CCD integration valuable and worthwhile, and many women reported direct and tangible benefits from participation. The primary benefits reported across participants were: (1) improved child-care practices; (2) increased partner involvement; (3) increased social support; and (4) improved quality of HIV services (Briggs & Garner, Citation2006).

Improved child-care practices

The vast majority of the mothers reported positive changes in their caregiving practices and attitudes as a result of the addition of CCD. They felt that the program changed the way that they raised their children, especially with regard to prioritizing play with their children and being physically near their children in order to be able to respond to their needs. When asked which aspects of the program were most important, women reported that topics on play and communication were most helpful, with many highlighting that it made them realise their children’s ability to interact with them, and the importance of play.

I was one of those people who saw playing with children as a waste of time as well, but now I have a suitcase of playing materials [that I use]. (Kasungu, 29 years old, 4 children)

[My interactions] have changed. I have learnt to be close to my child, to play with him, to take good care of him so my child is growing in a different way unlike my other children. (Kasungu, 32 years old, 5 children)

Mothers also reported greater self-confidence in parenting their current and any future children. In structured questions about the session content and the ability to practice CCD at home, mothers reported that the program reduced their anxieties about not being able to provide for all their children’s material needs.

I will continue taking care of my child using the same information I was taught [even] though I have graduated from the program. This will help my child to continue developing as well. (Kasungu, 26 years old, 2 children)

From what I have learnt I will be able to help my child develop well. Even if I decide to have another child, I will manage everything. (Kasungu, 29 years old, 4 children)

Increased partner involvement

An added benefit reported by the majority of respondents was increased father involvement. Even though the program did not directly engage fathers, women shared the ECD information and caregiving strategies with their male partners. The majority of women reported that fathers accepted and supported the ECD program, believing it was critical for the well-being of their children.

Most of the times when I am back from the lessons, I was explaining to the husband that this is what we have learnt … When he is with the child, he should also be able to do the things that I learnt. (Nkhotakota, 30 years old, 4 children)

Some fathers began committing financial resources into the program, ensuring that mothers were able to attend every session.

He (my husband) told me he didn’t want me to disappoint the counsellors. This meant that he also accepted and was happy with the program. He knew it was important because he was seeing how our child was growing. (Nkhotakota, 34 years old, 4 children)

My husband made sure that if there is no transport, he borrowed from friends and gave me … He made sure I never missed a session of the program because it was important. (Nkhotakota, 36 years old, 4 children)

Almost all participants reported that their partner had been supportive of her attendance, and many reported that the father spent more time with the child, and began playing games and making toys with the child.

When I am coming (home) he took part to ask me saying “What have you learnt my wife?”(Kasungu, 31 years old, 4 children)

My husband helped me with making some of the playing materials like a car, ball, and after he came back from work he played with him [the child] as well. (Kasungu, 29 years old, 4 children)

I shared with her father so that we can help each other doing what I learnt. Helping the child know things like showing her this is a bible, this is a spoon or plate. (Kasungu, 26 years old, 3 children)

Increased social support

Mothers also reported building a new social network and support system through the peer engagement components of the program. Mothers met monthly with the same 4–10 mothers who had children of similar ages. They were able to learn and practice positive child development strategies together. In addition, mothers had experienced similar challenges with their HIV status, motherhood, and home-life. During the CCD programme, mothers were able to build the trust needed to give advice and support to one another. Some mothers felt they had made friends with other mothers, and that they could help one another, and support one another.

There were others who have been affected for a long time and they were able to encourage us and we were able to discuss a lot of things about our health on the group. (Nkhotakota, 33 years old, 5 children)

Sometimes HIV positive mothers live with worries, when they have small children they think maybe the child will not live longer so by going to the hospital and learning together with fellow HIV positive mothers it was an important thing for me and my child. (Kasungu, 29 years old, 2 children)

Some mothers also reported increased support from their family members who saw positive outcomes from their participation in the program.

The whole family was happy. They were allowing me to spend the whole day (at the hospital) and to not miss sessions. (Nkhotakota, 35 years old, 1 living child)

Improved quality of HIV services

Participants reported that the quality of HIV services received improved after they joined the CCD program. They reported that the combined CCD-Option B+ services were provided faster and women felt more respected by health care providers. The program’s effect on the healthcare provider relationship was important to participants. Prior to the introduction of CCD, women were uncomfortable sharing information with the Option B+ health care providers because they felt providers were rude and judgmental. Upon enrolling in the CCD program and meeting regularly with their CCD counsellor, they felt their relationship with health providers improved, and that providers began to understand them and respond with kindness. This made them believe that providers were invested in both them as women and their children, and gave better quality services as a result. Some mothers also felt the pairing of the interventions was beneficial to their ART programme.

Before we enrolled in the program when going to the hospital we had a lot of difficulties as we could feel uncomfortable with the health caregivers. After we enrolled in the programme everything changed … We felt very comfortable getting the services at the hospital. (Kasungu, 31 years old, 4 children)

Things are much better than they were before. This time I receive the [HIV] services without problems. Before it was like we are in prison, but now they [providers] treat us well. (Kasungu, 35 years old, 4 children)

Sometimes we could forget about ART days, so these sessions acted as reminders as well. (Nkhotakota, 37 years old, 4 children)

Facilitators and barriers

Perceived facilitators and barriers to participating in the CCD programme were grouped into three categories: transport, time and stigma. Participants reported that they liked the opportunity to do two things at once — have their ART appointment and also engage in the CCD activities. They also felt that the CCD counsellors were accepting and non-judgmental, and that there was no HIV stigmatization of themselves or their children.

It was good because we did not spend much transport because we did two things at a time. (Kasungu, 26 years old, 2 children)

It was a good thing to me and I had no problem with it. We did two things at a time, getting treatment and attending session but both of these things happened within a short time. (Nkhotakota, 34 years old, 6 children)

In the past we were not comfortable. We were shy and we were stigmatizing ourselves … For example, I was feeling shy to get to that place [ART clinic] but since that time it is like we have been liberated. (Kasungu, 26 years old, 3 children)

When participants missed sessions, it was reportedly because they had difficulty finding transport to the hospital.

I missed these sessions because I did not have transport money. (Kasungu, 24 years old, 3 children)

Discussion

Our qualitative study found that the integration of an early childhood development intervention with ART delivery for women in Option B+ was acceptable and feasible and could lead to improved childhood development, which is especially important for exposed but uninfected infants, as well as for the health and wellbeing of HIV positive mothers (Nachega et al., Citation2012; Rochat, Netsi, et al., Citation2017). The mothers’ positive reports suggested that an integrated program may have a role to play in supporting treatment maintenance and adherence to ART.

The program also brought about a seeming shift in the quality of relationships between healthcare providers and mothers living with HIV, a feature that is common to other integrated interventions such as infant feeding (Mkwanazi et al., Citation2015; Rochat, Netsi, et al., Citation2017; Rochat et al., Citation2016). The participating mothers reported a definite improvement in providers’ attitudes, and they felt more accepted and comfortable in the clinic settings, a finding which is common to integrated programs focused on disclosure in later parenting (Mkwanazi et al., Citation2013; Rochat, Stein, et al., Citation2017). The integrated program showed potential in terms of the feasibility of task shifting and in decreasing stigma around clinic visits. Some mothers felt the integrated program could be improved if it was delivered by the same person at the same time.

Mothers living with HIV particularly liked learning about parenting and child development. Women felt empowered and more confident in their own capacity to parent, and evidence in the literature suggests this, in turn, can improve coping in the parenting role and reduce parenting stress (Rochat et al., Citation2011). A good early start, and support for nutrition and health care has been shown to improve not only maternal mental health in the longer term (Rochat, Houle, Stein, Pearson, Newell, et al., Citation2018) but also children’s cognitive development and their own mental health (Rochat et al., Citation2016; Rochat, Houle, Stein, Pearson, & Bland, Citation2018).

Some mothers reported increased engagement of fathers and support from others in the family. This is important as male involvement has been shown to be a substantial barrier in Manjate Cuco et al. (Citation2015). This occurred as a consequence of mothers sharing knowledge of childhood development and care with fathers, which they felt increased sharing and co-parenting engagement by the father, reducing child care burden, and creating a larger circle of care around the child. Importantly, responses illustrate the investment of fathers in the program and the sacrifices some made so that women could attend their sessions. This suggests that focusing on the child may provide an opening to engaging men in HIV and health care.

It is well established that HIV+ mothers struggle with depression or hopelessness (Sowa et al., Citation2015) and that the adjustment to parenting in parallel with HIV infection can be challenging (Rochat, Houle, Stein, Pearson, Newell, et al., Citation2018; Rochat, Stein, et al., Citation2017).

Given the strong evidence that maternal self-esteem and mental health can affect HIV adherence and compliance (Nachega et al., Citation2012), the positive empowering experience women reported from participation in this program could potentially have a spill-over effect to improved health care engagement and HIV treatment compliance, although this is still to be tested. Many women referenced the additional support gained from being part of a group of HIV positive mothers. This type of support has been shown to contribute to improved HIV, maternal mental health and child outcomes (Richter et al., Citation2014; Richter & Mofenson, Citation2014; Sherr et al., Citation2014).

The issue of transport cost and availability was raised as a barrier by many participants. Malawi is working hard to decentralize services to reduce logistical barriers to receiving ART by bringing services to the village level. It should be possible, at the same time, to integrate ECD and other services into decentralized ART distribution and this should be a priority given how the participants liked and enjoyed these sessions.

Integration of related services, including PMTCT with other sexual and reproductive services, child health and child development, could have multiple benefits. It streamlines client contact with the health system and reduces transport costs and time (Richter et al., Citation2014). In addition, a more holistic focus on the woman, her wellbeing, and her child may increase her motivation to stay in Option B+ and, by sharing information of human interest, such as on early childhood development, may help garner more support from her partner and her family (Richter, Citation2006). Women themselves, their partners and their families may be more willing to divert scarce resources to transport for clinic visits and tolerate a women’s absence from work in the home on clinic days, when the purpose of the visits extend beyond the mother and the family feel that they are gaining new information and skills that seems evidently to benefit a young child.

Next steps in exploring the benefits of integrating an early childhood development intervention into PMTCT Option B+ are to subject an integrated programme to empirical comparison with Option B+ delivered on its own, and to examine retention, adherence, maternal mental health, father engagement and childhood development outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed, S., Kim, M. H., & Abrams, E. J. (2013). Risks and benefits of lifelong antiretroviral treatment for pregnant and breastfeeding women: A review of the evidence for the Option B+ approach. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, 8(5), 474–489. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/COH.0b013e328363a8f2

- Briggs, C. J., & Garner, P. (2006). Strategies for integrating primary health services in middle-and low-income countries at the point of delivery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003318.pub2.

- Chang, S. M., Grantham-McGregor, S. M., Powell, C. A., Vera-Hernández, M., Lopez-Boo, F., Baker-Henningham, H., & Walker, S. P. (2015). Integrating a parenting intervention with routine primary health care: A cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics, 136(2), 272–280. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-0119.

- Chimbwandira, F., Mhango, E., Makombe, S., Midiani, D., Mwansambo, C., Njala, J., Chirwa, Z., Jahn, A., Schouten, E., & Phelps, B. R. (2013). Impact of an innovative approach to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV-Malawi, July 2011-September 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62(8), 148–151.

- Daelmans, B., Black, M. M., Lombardi, J., Lucas, J., Richter, L., Silver, K., Britto, P., Yoshikawa, H., Perez-Escamilla, R., MacMillan, H., Dua, T., Bouhouch, R. R., Bhutta, Z., Darmstadt, G. L., & Rao, N. (2015). Effective interventions and strategies for improving early child development. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 351, h4029. https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/351/bmj.h4029.full.pdf https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4029

- DiGirolamo, A. M., Stansbery, P., & Lung'aho, M. (2014). Advantages and challenges of integration: Opportunities for integrating early childhood development and nutrition programming. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1308(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12323

- Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/798843

- Gourlay, A., Birdthistle, I., Mburu, G., Iorpenda, K., & Wringe, A. (2013). Barriers and facilitating factors to the uptake of antiretroviral drugs for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in sub-saharan Africa: A systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16(1), 18588. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.16.1.18588

- Lucas, J. E., Richter, L. M., & Daelmans, B. (2018). Care for child development: An intervention in support of responsive caregiving and early child development. Child: Care, Health and Development, 44(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12544

- Manjate Cuco, R. M., Munguambe, K., Bique Osman, N., Degomme, O., Temmerman, M., & & Sidat, M. M. (2015). Male partners’ involvement in prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 12(1), 87–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17290376.2015.1123643

- Mkwanazi, N. B., Rochat, T. J., & Bland, R. M. (2015). Living with HIV, disclosure patterns and partnerships a decade after the introduction of HIV programmes in rural South Africa. AIDS Care, 27(sup1), 65–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2015.1028881

- Mkwanazi, N. B., Rochat, T. J., Coetzee, B., & Bland, R. (2013). Mothers’ and health workers’ perceptions of participation in a child-friendly health initiative in rural South Africa. Health, 05(12), 2137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4236/health.2013.512291

- Myer, L., Phillips, T. K., Zerbe, A., Brittain, K., Lesosky, M., Hsiao, N.-Y., Remien, R. H., Mellins, C. A., McIntyre, J. A., & Abrams, E. J. (2018). Integration of postpartum healthcare services for HIV-infected women and their infants in South Africa: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS Medicine, 15(3), e1002547. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002547

- Nachega, J. B., Uthman, O. A., Anderson, J., Peltzer, K., Wampold, S., Cotton, M. F., Mills, E. J., Ho, Y.-H., Stringer, J. S. A., & McIntyre, J. A. (2012). Adherence to antiretroviral therapy during and after pregnancy in low-, middle and high income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aids (london, England), 26(16), 2039. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359590f

- Paudel, V., & Baral, K. P. (2015). Women living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA), battling stigma, discrimination and denial and the role of support groups as a coping strategy: A review of literature. Reproductive Health, 12(1), 53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-015-0032-9

- Powis, K. M., Slogrove, A. L., & Mofenson, L. (2017). Protecting the health of our AIDS free generation–beyond prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission. Aids (London, England), 31(2), 315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001315

- Richter, L. M. (2006). The role of the health sector in strengthening systems to support children's healthy development in communities affected by HIV/AIDS: A review. World Health Organization.

- Richter, L. M., Daelmans, B., Lombardi, J., Heymann, J., Boo, F. L., Behrman, J. R., Lu, C., Lucas, J. E., Perez-Escamilla, R., & Dua, T. (2017). Investing in the foundation of sustainable development: Pathways to scale up for early childhood development. The Lancet, 389(10064), 103–118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31698-1

- Richter, L. M., & Mofenson, L. M. (2014). Children born into families affected by HIV. Aids (London, England), 28(Supplement 3), S241–S244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000361

- Richter, L. M., Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Van Heerden, A., Stein, A., Tomlinson, M., Harwood, J. M., Rochat, T., Van Rooyen, H., Comulada, W. S., & Tang, Z. (2014). Pregnant women living with HIV (WLH) supported at clinics by peer WLH: A cluster randomized controlled trial. AIDS and Behavior, 18(4), 706–715. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0694-2

- Rochat, T. J., Bland, R., Coovadia, H., Stein, A., & Newell, M.-L. (2011). Towards a family-centered approach to HIV treatment and care for HIV-exposed children, their mothers and their families in poorly resourced settings. Future Virology, 6(6), 687–696. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2217/fvl.11.45

- Rochat, T. J., Houle, B., Stein, A., Coovadia, H., Coutsoudis, A., Desmond, C., Newell, M.-L., & Bland, R. M. (2016). Exclusive breastfeeding and cognition, executive function, and behavioural disorders in primary school-aged children in rural South Africa: A cohort analysis. PLoS Medicine, 13(6), e1002044. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002044

- Rochat, T. J., Houle, B., Stein, A., Pearson, R. M., & Bland, R. M. (2018). Prevalence and risk factors for child mental disorders in a population-based cohort of HIV-exposed and unexposed African children aged 7–11 years. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(12), 1607–1620. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1146-8

- Rochat, T. J., Houle, B., Stein, A., Pearson, R. M., Newell, M.-L., & Bland, R. M. (2018). Psychological morbidity and parenting stress in mothers of primary school children by timing of acquisition of HIV infection: A longitudinal cohort study in rural South Africa. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, 9(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S204017441700068X

- Rochat, T. J., Netsi, E., Redinger, S., & Stein, A. (2017). Parenting and HIV. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 155–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.019

- Rochat, T. J., Stein, A., Cortina-Borja, M., Tanser, F., & Bland, R. M. (2017). The Amagugu intervention for disclosure of maternal HIV to uninfected primary school-aged children in South Africa: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet HIV, 4(12), e566–e576. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30133-9

- Schwartz, S. R., Rees, H., Mehta, S., Venter, W. D. F., Taha, T. E., & Black, V. (2012). High incidence of unplanned pregnancy after antiretroviral therapy initiation: Findings from a prospective cohort study in South Africa. PLoS one, 7(4), e36039. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036039

- Sherr, L., Cluver, L. D., Betancourt, T. S., Kellerman, S. E., Richter, L. M., & Desmond, C. (2014). Evidence of impact: Health, psychological and social effects of adult HIV on children. Aids (London, England), 28(Supplement 3), S251–S259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000327

- Sowa, N. A., Cholera, R., Pence, B. W., & Gaynes, B. N. (2015). Perinatal depression in HIV-infected African women: A systematic review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(10), 1385–1396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14r09186

- UNAIDS. (2016). Country Factsheet: Malawi | HIV/ AIDS estimates.

- WHO. (2014). Implementation of Option B+ for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: the Malawi experience.