ABSTRACT

Few longitudinal studies have measured trends and effects of disclosure over ART scale-up in general-population samples. We investigated levels, determinants and outcomes of disclosure to relatives and partners in a large general-population cohort in Zimbabwe. Trends in disclosure levels from 2003 to 2013 were analysed, and multivariable logistic regression was used to identify determinants. Longitudinal analyses were conducted testing associations between disclosure and prevention/treatment-related outcomes. Disclosure to anyone increased from 79% to 100% in men and from 63% to 98% in women from 2003 to 2008; but declined to 89% in both sexes in 2012–2013. More women than men disclosed to relatives (67.8% versus 44.4%; p < 0.001) but fewer women disclosed to partners (85.3% versus 95.0%; p < 0.001). In 2012–2013,secondary/higher education, being single, and experience of stigma were associated with disclosure to relatives in both sexes. Partner characteristics and HIV-group attendance were associated with disclosure to partners for women. Reactions to disclosure were generally supportive but less so for females than males disclosing to partners (92.0% versus 97.4%). Partner disclosure was weakly associated (p < 0.08) with having had a CD4 count or taken ART at follow-up in females. To conclude, this study shows disclosure is vital to HIV prevention and treatment, and programmes to facilitate disclosure should be re-invigorated.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Disclosure of HIV-infected status is vital for prevention and treatment, with benefits seen for individuals and public health. For individuals, disclosure allows access to support and can improve psychological well-being and facilitate treatment. Obermeyer et al. found that, for most, disclosure to partners, friends and relatives elicit supportive reactions (Obermeyer et al., Citation2011), and disclosure to partners (Kiene et al., Citation2018; Rodriguez et al., Citation2018) and loved-ones (Tesfaye & Bune, Citation2014) often correlates with reduced anxiety and depression. For those not disclosing, fear that others will learn their status and lack of support act as barriers to treatment-seeking and adherence (Madiba & Letsoalo, Citation2013; Stinson & Myer, Citation2012). Disclosure is closely linked to good ART adherence (Omonaiye et al., Citation2018) which is important for HIV prevention, and the well-being of people living with HIV (PLHIV). Negative reactions may be rare but seem to disproportionately affect women, ranging from blame and stigma to physical abuse (Obermeyer et al., Citation2011). For public health, disclosure to those who have been exposed encourages them to be tested and treated (Bhatia et al., Citation2017); and disclosure to partners can prevent transmission by encouraging partner reduction and condom use (Booysen et al., Citation2017; Vu et al., Citation2012).

It is crucial therefore to identify where and why there are gaps in disclosure so that these can be addressed (UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), Citation2000). Multiple determinants of disclosure have been identified including socio-demographic and HIV testing and counselling factors. Determinants and experiences of disclosure often differ between men and women in ways that depend heavily on the social context (Anglewicz & Chintsanya, Citation2011; Brown et al., Citation2019). Disclosure is often higher in more educated individuals (Bott & Obermeyer, Citation2013) but the roles of age (Abdool et al., Citation2015; Vu et al., Citation2012), employment (Obermeyer et al., Citation2011), and socio-economic status (Brittain et al., Citation2018; Patel et al., Citation2012) vary. Socio-cultural factors such as damaging media representations (Muparamoto & Chiweshe, Citation2015) and negative societal beliefs about PLHIV can be barriers to disclosure (O’Brien & Broom, Citation2013). Experience of living with HIV and of testing and counselling are also important (Obermeyer et al., Citation2011). Disclosure is more likely in those experiencing symptoms (Ssali et al., Citation2010; Wong et al., Citation2009), at more advanced illness (Dageid et al., Citation2012), and on ART (Abdool et al., Citation2015; Vu et al., Citation2012). Women tested in voluntary facilities are more likely to disclose than those tested at antenatal clinics (Erku et al., Citation2012). Prior discussion of testing with partners (Makin et al., Citation2008) and undergoing tests as a couple (Spangler et al., Citation2018) facilitate disclosure, as does counselling and attending support groups (Erku et al., Citation2012).

In investigating disclosure determinants, studies frequently look at disclosure “to anyone” as a single outcome (Preau et al., Citation2015). This is problematic because there can be important differences in the consequences for prevention and treatment between disclosure to a sexual partner and disclosure to a relative (Ssali et al., Citation2010). Also, determinants of, and reactions to, disclosure can differ depending on who the disclosure is to (Brittain et al., Citation2018; Spangler et al., Citation2018). Obermeyer et al.’s review found that disclosure is more often to family than friends and that patterns of disclosure to partners vary greatly from those to other targets (Obermeyer et al., Citation2011). Partner (Tam et al., Citation2015) and partnership characteristics affect disclosure: being married, living with a partner (Trinh et al., Citation2016), and being in a regular (versus casual) (Abdool et al., Citation2015) or a monogamous (versus polygamous) relationship (Udigwe et al., Citation2013) can all increase disclosure to partners.

An important limitation in the current literature, particularly for Zimbabwe (Mccoy et al., Citation2015; Patel et al., Citation2012; Shamu et al., Citation2014), is a predominance of small-scale cross-sectional clinical studies (Kangwende et al., Citation2009; Marembo et al., Citation2014; Mucheto et al., Citation2011; Patel et al., Citation2012; Tarwirey, Citation2005), with few studying men (Kangwende et al., Citation2009; Tarwirey, Citation2005) or quantifying disclosure outcomes (Patel et al., Citation2012; Shamu et al., Citation2014). Few studies have examined whether the gaps identified in clinical settings represent those in the general-population (Abdool et al., Citation2015; Anglewicz & Chintsanya, Citation2011; Doherty et al., Citation2016; Simbayi et al., Citation2017), and few studies have measured trends in levels, determinants and effects of disclosure over time (Haberlen et al., Citation2015); particularly in response to ART scale-up. This is important because changes such as increases in early diagnosis and reduced emphasis on pre- and post-test counselling could have altered levels and patterns of disclosure. Longitudinal cohort studies are needed to provide information on causal associations, and more data are needed on disclosure by HIV-positive men (Kangwende et al., Citation2009; Tarwirey, Citation2005).

This study aims to help fill these literature gaps using data from a large (N∼10,000) general-population open-cohort HIV sero-survey to investigate the following for PLHIV in Zimbabwe:

Whether levels of disclosure changed over the scale-up of ART services;

How disclosure levels to family (2a) and to partners (2b) vary by socio-demographic characteristics and HIV testing and counselling (HTC) factors; and

Individual (3a) and social outcomes (3b) of disclosure.

Methods

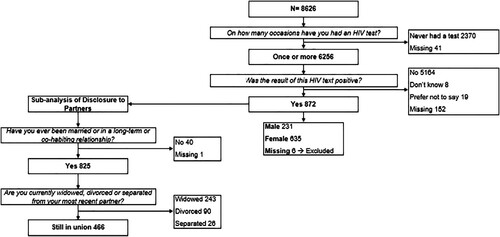

The Manicaland cohort was established to provide data on HIV prevalence, incidence, risk behaviours and consequences, in a population suffering a generalised HIV epidemic. Six rounds of data collection (questionnaires) were conducted from 1998 to 2013 with adults aged 15–54 years (Gregson et al., Citation2017; “Manicaland HIV Project,” Citation2019). Questionnaires were checked for accuracy and completeness by supervisors in the field, data-processing tools and data-cleaning at completion (see Gregson et al., Citation2017 for full details including participation rates and cohort demographics/epidemiology). Self-reported HIV-positive survey participants were eligible for the current study (see for round 6 details and exclusion criteria and Appendix 1 for other rounds). Disclosure questions were included from round three of the survey (2003–2005), when HTC and ART services were scaled-up in Zimbabwe, and so analysis of disclosure trends was restricted to 2003–2013.

Figure 1. Procedure for identifying HIV-positive participants and those with partners for the sub-analysis of disclosure to partners, including exclusion criteria, round 6, 2012–2013.

Disclosure is defined here as sharing of an HIV-positive status (since only those self-reported as HIV-positive were included), and the nature of the disclosure (voluntary or involuntary) was not studied. Disclosure data were extracted from the question “With whom have you shared your test results?”. Composite variables for “disclosure to anyone” and “disclosure to family” were created by grouping responses (see Appendix 2). For disclosure to partners, only those with current partners were included. Chi-squared tests were used to test for differences in proportions of PLHIV disclosing to disclosure targets between survey rounds. Logistic regression was used to test for differences in disclosure to different parties between genders in each round.

Cross-sectional analysis using multivariable logistic regression was conducted to test for associations between determinants of disclosure and disclosure to family and to a partner using data from round six. Hypothesised determinants were identified a priori, and tested for significance in univariate logistic regression (adjusted only for age). Those significant at p < 0.1 were included in the fully adjusted model. Separate models were created for “disclosure to family” and for “disclosure to partner”.

Grouped variables were created for religion (using church groupings by Manzou et al. (Citation2014)), alcohol use, and “experiencing symptoms” (Appendix 2). Of note, the “experienced stigma” variable could be a determinant or outcome of disclosure in this cross-sectional analysis. Some hypothesised determinants including socio-economic status and location of HIV testing could not be analysed from the data. Missing data on disclosure to family/partners was <10% of responses and evenly distributed across sub-categories of independent variables studied, and so was assumed to be missing completely at random.

Chi-squared tests were used to test for differences in supportive reactions from different disclosure targets. Prospective longitudinal analyses, using logistic regression, were conducted to test for associations between disclosure prior to 2009/11 and between 2009/11 and 2012/13 versus never-disclosure at 2012/13 and outcome variables of disclosure consequences at 2012/13. Only those followed-up between the last two rounds of the survey therefore were included in this analysis (overall follow-up was 77% between rounds 5 and 6) (Gregson et al., Citation2017). Outcome variables were again identified a priori. Regressions were adjusted for age and outcomes at baseline (2009/11). Missing data for disclosure consequences were minimal.

All data were anonymised in the cohort database. Ethical approval for the cohort was provided by Imperial College London Research Ethics Committee (ICREC_9_3_13) and Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ/A/681).

Results

Objective 1 – disclosure trends, 2003–2013

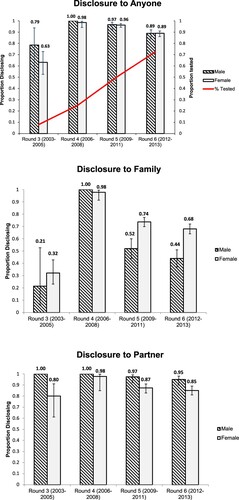

The percentage of adults in Manicaland tested for HIV increased steadily (from 8% to 73%). The proportion disclosing to anyone increased from 79% to 100% (p = 0.09) in men and from 63% to 98% (p = <0.001) in women from 2003 to 2008; but declined to 89% in both sexes (p = 0.3; p = <0.001) in 2012–2013 (). Trends in proportions disclosing to family and partners were similar, but proportions disclosing to family were lower than to partners (). Disclosure to family was generally higher for women than men, whilst the opposite was true for disclosure to partners. These differences in disclosure by gender were statistically significant adjusted for age and settlement type in 2009/11 and 2012/13 (p < 0.001 throughout).

Objective 2 – disclosure determinants, 2012/13

Disclosure to family

Socio-demographic characteristics

Women and men with a current spouse/partner were less likely to have disclosed their HIV-positive status to family than those without (). For women, this association persisted in the fully adjusted model (AOR = 0.44; p < 0.01). For men, there was collinearity between relationship status and age; however, after excluding age from the model the association remained (AOR = 0.37, 95% CI, 0.16–0.87; p = 0.02).

Table 1. Determinants of disclosure of status by HIV-infected men and women to family members, Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 2012–2013.

No associations with age were found for women, but younger men (15–29 years) were more likely to disclose to family than older men (≥30 years) in age-adjusted and fully adjusted models (). Greater education had higher odds of disclosure for both sexes. Women with a recent pregnancy (<3 years ago) were statistically significantly less likely to have disclosed in age-, but not fully adjusted models. Women in more urban settlements (towns and roadside settlements) and women working informally – but not formally – had lower odds of disclosing to family than those living in subsistence farming areas or who were unemployed, respectively, in age- and fully adjusted models. For men, no associations with disclosure were found for settlement type or employment status.

Experience of stigma was positively associated with disclosure to family for both sexes, with the association persisting in fully adjusted models (men: AOR = 3.13; p = 0.03; women: AOR = 3.17; p = 0.01).

HIV testing and counselling factors

For women, in the age-adjusted models, those receiving longer post-test counselling (>45 min versus ≤15 min) and those with a single follow-up counselling session (versus none) had lower odds of family disclosure. Those attending an HIV group, tested 1–4 years and 4–5 years ago (versus <6 months ago), and those with symptoms were more likely to have disclosed. In fully adjusted models, women with longer post-test counselling sessions continued to have lower odds of disclosure (OR = 0.37; p = 0.01) and those tested longer ago (4–5 years) (OR = 2.46; p = 0.02) and those with symptoms still had higher odds of disclosure (OR = 2.99; p < 0.01).

For men, in the age-adjusted models, those tested 7–12 months ago – but not those tested >12 months previously – had higher odds of disclosure to family than those tested <6 months ago (AOR = 2.80; p = 0.01); as did men receiving multiple follow-up counselling sessions (versus none) (AOR = 2.38; p = 0.02). Men told or persuaded to get tested (versus choosing to test) and those tested in a couple had borderline significant (p < 0.1) greater odds of disclosing. In fully adjusted models, men tested 7–12 months ago still had higher odds of disclosing (OR = 2.81; p = 0.02).

Disclosure to partners

Socio-demographic characteristics

Of the 54% of participants with partner’s, relationships between socio-demographic and HTC factors and disclosure to partners differed from those with disclosure to family (). Older women (≥50 years) were less likely to disclose to partners than young women (<30 years) in the fully adjusted model (AOR = 0.04; p = 0.03) but no associations with age were found for men.

Table 2. Determinants of disclosure of status by HIV-infected men and women to sexual partners, Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 2012–2013.

Women with greater education had lower odds of disclosure to partners in the fully adjusted model (AOR = 0.16; p = 0.04). Men with greater education were more likely to disclose their status to their partners but the difference was not statistically significant (AOR = 3.24; p = 0.17). For women, in the age-adjusted model, Apostolic church membership (versus Christian church), working – or having a partner working – in the informal sector (versus unemployed), living in a town (versus subsistence farming area), and having a less-educated partner (p = 0.08) were associated with less disclosure. The associations for partner’s employment and urban residence remained in the fully adjusted model. For men, in the age-adjusted model, having no religion (versus Christian church membership) and formal employment (versus unemployed) were associated with reduced odds of disclosure to partners but neither effect was statistically significant in the fully adjusted model.

HIV testing and counselling factors

For women, in the age-adjusted models, those receiving longer post-test counselling (>45 min versus ≤15 min) had lower odds of disclosure to partners. Women who knew their last partner’s HIV status and those who attended an HIV group were more likely to have disclosed. In the fully adjusted model, the effects of longer post-test counselling (AOR = 0.01; p < 0.001) and attending HIV groups (AOR = 5.11; p = 0.02) remained statistically significant.

For men, in the age-adjusted models, those with symptoms disclosed less to partners, and those who attended post-test counselling with their partner had a borderline statistically significant positive association with disclosure. In the fully adjusted model, the association with the experience of symptoms strengthened (AOR = 0.04; p = 0.01).

Objective 3 – disclosure outcomes, 2009–2013

Individual outcomes

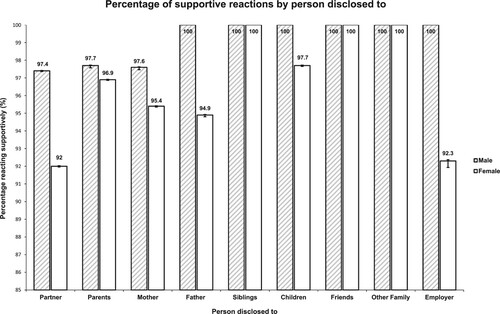

shows how different people reacted to disclosure. Overall, most were supportive with 100% of those disclosing to siblings, friends and other family members in 2012/13 reporting supportive reactions. Fewer women than men reported supportive reactions from partners, parents, children and employers. However, proportions of supportive reactions were still high in these groups; being lowest for women disclosing to partners (92%).

The results for other individual and social outcomes are shown in . For women who disclosed to their families, no differences in outcomes at follow-up (2012/13) were found between those who had disclosed before baseline (2009/11) and those who had still to disclose at follow-up. Women who disclosed between baseline and follow-up were more likely to feel socially supported (88.6% versus 69.6%; AOR = 3.51; p = 0.03) but also to report having experienced violence (14.3% versus 2.3%; AOR = 8.1; p = 0.06). There were non-significant trends for other negative consequences: poor mental health, experiencing stigma, and finding the community discriminatory. For men, no statistically significant associations were found. For those who disclosed during the inter-survey period (2009–2013), there was a positive association with feeling socially supported but negative associations (AOR>2) for poor mental health, stigma, and finding the community discriminatory. No clear trends were apparent in the health-care seeking outcomes.

Table 3. Individual and social outcomes of disclosure of HIV infection status to family and sexual partners, Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 2009–2013.

For women’s disclosure to partners, reference group (never disclosed) numbers were small but there was weak evidence for less poor mental health at follow-up (2012/13) in women who had already disclosed to partners at baseline (2009/11) (AOR = 0.35; p = 0.09); and for less self-stigma at follow-up in those who disclosed between baseline and follow-up (AOR = 0.11; p = 0.09). There was weak evidence for an association between disclosure to partners at baseline and having had a CD4 count and having taken ART at follow-up (p = 0.08 for both).

Social outcomes

Women who had disclosed to partners at baseline were less likely than those who had never disclosed to report having reduced their numbers of partners after testing at follow-up (5.7% versus 23.1%; AOR = 0.14; p = 0.03). However, there were higher odds of increasing condom use (OR = 14.81; p = 0.04) and of taking HIV prevention steps (OR = 6.3; p = 0.07), in those disclosing between baseline and follow-up compared to those who never disclosed. Sample sizes were too small for analysis in men.

Discussion

This research aimed to understand HIV disclosure in Zimbabwe, through an investigation of its levels, determinants and outcomes in a general-population sample. Overall, disclosure of HIV-positive status was found to be complex and nuanced, echoing existing literature. In 2003–2005, before HIV testing and treatment services became widely available, disclosure to partners was already quite high but disclosure to family was low. From 2005 to 2008, uptake of HIV testing began to increase and disclosure to both partners and family became almost universal; but, in the following years, reductions in disclosure occurred particularly in disclosure to family. This finding differs from the only previously published longitudinal analysis in a sub-Saharan African population where disclosure increased in both pre- and post-ART periods (Haberlen et al., Citation2015). Trends in disclosure within the post-ART era are not well researched, but possible explanations for declines include reduced emphasis on counselling in testing services (Church et al., Citation2015), which previously stressed the importance of support from loved-ones (and hence of disclosure) (Bohle et al., Citation2014), and fewer symptoms due to earlier diagnosis and treatment (Klitzman et al., Citation2004).

Levels of disclosure to anyone were similar for both sexes in 2012/13. The proportion of women disclosing their HIV status to anyone in the general-population in Manicaland was higher than in clinical settings in Zimbabwe at a similar time (Marembo et al., Citation2014; Mccoy et al., Citation2015; Mucheto et al., Citation2011). As elsewhere in Africa (Evans et al., Citation2016; Tam et al., Citation2015), for both sexes, disclosure to partners was more common than disclosure to family; probably motivated by desire to prevent transmission (Bhatia et al., Citation2017; Erku et al., Citation2012; Ssali et al., Citation2010; Tshweneagae et al., Citation2015). Similar to South Africa (Abdool et al., Citation2015), more men than women disclosed to partners, likely reflecting well-documented gender imbalances in relationships (Hardon et al., Citation2012; Madiba & Letsoalo, Citation2013; Maman et al., Citation2001; Ssali et al., Citation2010; Tumwine et al., Citation2012); and more women than men disclosed to family. In both sexes, those with partners were less likely to disclose to family.

Generally, associations between socio-demographic factors and disclosure differed by person disclosed to and between women and men, highlighting that disclosure differs greatly by gender (Bhagwanjee et al., Citation2011; Bhatia et al., Citation2017; Bott & Obermeyer, Citation2013; Brown et al., Citation2019; Ssali et al., Citation2010). For women, those with greater education were more likely to disclose to family and less likely to disclose to partners; and, for men, those with symptoms were non-significantly more likely to disclose to family but less likely to disclose to partners. Women and men had contrasting determinants of disclosure: greater education (Bott & Obermeyer, Citation2013) and longer times since diagnosis (Bachanas et al., Citation2013; Kangwende et al., Citation2009) increased disclosure to family in both sexes; but disclosure to partners varied for women – but not for men – by age, education, settlement, employment, length of post-test counselling, and partner’s characteristics (Makin et al., Citation2008).

The findings that PLHIV disclosing to family receive supportive reactions (Patel et al., Citation2012) and feel socially supported, and that those disclosing to partners increase condom use are important for treatment and prevention, respectively. However, in the cross-sectional analysis, for both sexes, disclosure to family was associated with experiences of stigma. Caution is needed in interpreting the longitudinal results due to small sample sizes but it is concerning that negative outcomes appear to be common. Unlike an earlier study in Zimbabwe (Shamu et al., Citation2014), women’s disclosure to male partners did not increase domestic violence but worryingly there was some evidence that disclosure to family may be linked to violence and women received significantly less supportive reactions from their partners.

This study is the first evaluation of disclosure in a longitudinal general-population sample in Zimbabwe and is unusual in providing analyses that compare the determinants and effects of disclosure to family and partners for women and men. However, limitations include small sample sizes for some analyses and lack of a qualitative component. The results may be subject to social desirability bias and selection bias due to loss-to-follow-up.

Subject to these limitations, the study findings highlight the importance of disclosure for prevention and treatment, the need to re-invigorate programmes to re-establish universal disclosure to both families and partners, and the important roles of couple testing / knowledge of partners status, counselling including follow-up counselling (De Rosa & Marks, Citation1998; Erku et al., Citation2012; Maman et al., Citation2001; Norman et al., Citation2007), and HIV support groups in bringing about disclosure and supporting those who disclose. It may not be a coincidence that disclosure levels declined when counselling in HIV testing services was downplayed in the drive to increase treatment coverage.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the study participants for providing the data needed for this study and to the Manicaland Centre team for conducting the data collection and processing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdool, Q., Della, R., Bearnot, B., Werner, L., Frohlich, J. A., Kharsany, A. B. M., & Abdool, S. S. (2015). HIV-positive status disclosure in patients in care in rural South Africa: Implications for scaling up treatment and prevention interventions. AIDS and Behavior, 19(1), 322–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0951-4

- Anglewicz, P., & Chintsanya, J. (2011). Disclosure of HIV status between spouses in rural Malawi. Aids Care, 23(8), 998–1005. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2010.542130

- Bachanas, P., Medley, A., Pals, S., Antelman, G., Benech, I., Deluca, N., Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha, H., Muhenje, O., Cherutich, P., Kariuki, P., & Katuta, F. (2013). Disclosure, knowledge of partner status, and condom. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 27(7). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2012.0388

- Bhagwanjee, A., Govender, K., Akintola, O., Petersen, I., George, G., Johnstone, L., & Naidoo, K. (2011). Patterns of disclosure and antiretroviral treatment adherence in a South African mining workplace programme and implications for HIV prevention. African Journal of AIDS Research, 10(1), 357–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2011.637737

- Bhatia, D. S., Wilson, I. B., Role, T., & Harrison, A. D. (2017). The role of relationship dynamics and gender inequalities as barriers to HIV-serostatus disclosure: Qualitative study among women and men living with HIV in Durban, South Africa. Frontiers in Public Health, 5(188), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00188

- Bohle, L. F., Dilger, H., & Groß, U. (2014). HIV-serostatus disclosure in the context of free antiretroviral therapy and socio-economic dependency: Experiences among women living with HIV in Tanzania. African Journal of AIDS Research, 13(3), 215–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2014.952646

- Booysen, R., Wouters, E., Walque, D., & Over, M. (2017). Mutual HIV status disclosure is associated with consistent condom use in public sector ART clients in free state province, South Africa : A short report. AIDS Care, 29(11), 1386–1390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2017.1290210

- Bott, S., & Obermeyer, C. M. (2013). The social and gender context of HIV disclosure in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of policies and practices. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 10(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2012.755319

- Brittain, K., Mellins, C. A., Remien, R. H., Phillips, T., Zerbe, A., Abrams, E. J., & Myer, L. (2018). Patterns and predictors of HIV-status disclosure among pregnant women in South Africa: Dimensions of disclosure and influence of social and economic circumstances. AIDS and Behavior, 22(12), 3933–3944. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2263-6

- Brown, L., Getahun, M., Ayieko, J., Kwarisiima, D., Owaraganise, A., Atukunda, M., Olilo, W., Clark, T., Bukusi, E.A., Cohen, C.R. and Kamya, M.R., & Id, C. S. C. (2019). Factors predictive of successful retention in care among HIV-infected men in a universal test-and-treat setting in Uganda and Kenya : A mixed methods analysis. PLoS ONE, 1, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210126

- Church, K., Kiweewa, F., Dasgupta, A., Mwangome, M., Mpandaguta, E., Gómez-olivé, F. X., Oti, S., Todd, J., Wringe, A., Geubbels, E., Crampin, A., Nakiyingi-Miiro, J., Hayashi, C., Njage, M., Wagner, R. G., Ario, A. R., Makombe, S. D., Mugurungi, O., & Zaba, B. (2015). A comparative analysis of national HIV policies in six African countries with generalized epidemics. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 93(9), 457–467. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.14.147215

- Dageid, W., Govender, K., & Gordon, S. F. (2012). Masculinity and HIV disclosure among heterosexual South African men: Implications for HIV / AIDS intervention. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 14(8), 925–940. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.710337

- De Rosa, C. J., & Marks, G. (1998). Preventive counseling of HIV-positive men and self-disclosure of serostatus to sex partners: New opportunities for prevention. Health Psychology, 17(3), 224–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.17.3.224

- Doherty, I. A., Myers, B., Zule, W. A., Minnis, A. M., Kline, T. L., Parry, C. D., El-Bassel, N., & Wechsberg, W. M.(2016). Seek, test and disclose : knowledge of HIV testing and serostatus among high-risk couples in a South African township. 5–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2014-051882

- Erku, T., Megabiaw, B., & Wubshet, M. (2012). Predictors of HIV status disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia. Pan African Medical Journal, 87(13), 1–12.

- Evans, H., Hewson, D., & Pappas, Y. (2016). Factors influencing HIV disclosure among people living with HIV / AIDS in Nigeria : A systematic review using narrative synthesis and. Public Health, 136, 13–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.02.021

- Gregson, S., Mugurungi, O., Eaton, J., Takaruza, A., Rhead, R., Maswera, R., Rufurwokuda, M. J., Mayini, J., Skovdal, M., Schaefer, R., Hallett, T., Sherr, L., Munyati, S., Mason, P., Campbell, C., Garnett, G. P., & Nyamukapa, C. A. (2017). Documenting and explaining the HIV decline in east Zimbabwe : The Manicaland General population cohort. BMJ Open, 7(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015898

- Haberlen, S. A., Nakigozi, G., Gray, R. H., Brahmbhatt, H., Ssekasanvu, J., Serwadda, D., Nalugoda, F., Kagaayi, J., & Wawer, M. J. (2015). Antiretroviral therapy availability and HIV disclosure to spouse in Rakai, Uganda : A longitudinal population-based study. Epidemiology and Prevention, 69(2), 241–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000600

- Hardon, A., Vernooij, E., Bongololo-mbera, G., Cherutich, P., Desclaux, A., Kyaddondo, D., Ky-Zerbo, O., Neuman, M., Wanyenze, R., & Obermeyer, C. (2012). Women’s views on consent, counseling and confidentiality in PMTCT: A mixed-methods study in four African countries. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-26

- Kangwende, R., Chirenda, J., & Mudyiradima, R. (2009). HIV status disclosure among people living with HIV/AIDS at FASO, Mutare, Zimbabwe. The Central African Journal of Medicine, 55(4), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4314/cajm.v55i1-4.63632

- Kiene, S. M., Dove, M., & Wanyenze, R. K. (2018). Depressive symptoms, disclosure, HIV-related stigma, and coping following HIV testing among outpatients in Uganda: A daily process analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 22(5), 1639–1651. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1953-9

- Klitzman, R. L., Kirshenbaum, S. B., Dodge, B., Remien, R. H., Ehrhardt, A. A., Johnson, M. O., Kittel, L. E., Daya, S., Morin, S. F., Kelly, J., Lightfoot, M., & Rotheram-borus, M. J. (2004). Intricacies and inter-relationships between HIV disclosure and HAART: A qualitative study. AIDS Care, 16(5), 628–640. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120410001716423

- Madiba, S., & Letsoalo, R. (2013). HIV disclosure to partners and family among women enrolled in prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV program: Implications for infant feeding in poor resourced Communities in South Africa. Global Journal of Health Science, 5(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v5n4p1

- Makin, J. D., Forsyth, B. W. C., Visser, M. J., Sikkema, K. J., Ph, D., Neufeld, S., Jeffery, B., & Mmed, O. (2008). Factors affecting disclosure in South African HIV-positive pregnant women. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 22(11), 907–917. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2007.0194

- Maman, S., Mbwambo, J., Hogan, N. M., Kilonzo, G. P., & Sweat, M. (2001). Women’s barriers to HIV-1 testing and disclosure: Challenges for HIV-1 voluntary counselling and testing. AIDS Care, 13(5), 595–603. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120120063223

- Manicaland HIV Project. (2019, May 5). http://www.manicalandhivproject.org/

- Manzou, R., Schumacher, C., & Gregson, S. (2014). Temporal dynamics of religion as a determinant of HIV infection in east Zimbabwe: A serial cross-sectional analysis. PLoS ONE, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086060

- Marembo, J., Zvinavashe, M., Nyamakura, R., Shaibu, S., & Mogobe, K. D. (2014). Factors influencing infant-feeding choices selected by HIV-infected mothers: Perspectives from Zimbabwe. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 11(1), 259–267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12027

- Mccoy, S. I., Buzdugan, R., Padian, N. S., Musarandega, R., Engelsmann, B., Martz, T. E., Mushavi, A., Mahomva, A., & Cowan, F. M. (2015). Uptake of services and behaviors in the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission cascade in Zimbabwe. Implementation and Operational Research: Epidemiology and Prevention, 69(2), 74–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000597

- Mucheto, P., Chadambuka, A., Shambira, G., Tshimanga, M., Notion, G., & Nyamayaro, W. (2011). Determinants of nondisclosure of HIV status among women attending the prevention of mother to child transmission programme, Makonde district, Zimbabwe, 2009. Pan African Medical Journal, 51(8), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4314/pamj.v8i1.71169

- Muparamoto, N., & Chiweshe, M. K. (2015). “Managing identities” and parental disclosure of HIV sero-status in Zimbabwe. African Journal of AIDS Research, 14(2), 145–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2015.1040804

- Norman, A., Chopra, M., & Kadiyala, S. (2007). Factors related to HIV disclosure in 2 South African communities. American Journal of Public Health, 97(10), 1775–1781. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.082511

- Obermeyer, C. M., Baijal, P., & Pegurri, E. (2011). Facilitating HIV disclosure facilitating HIV disclosure across diverse settings : A review. Health Policy and Ethics, 101(6), 1011–1023. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300102

- O’Brien, S., & Broom, A. (2013). Gender, culture and changing attitudes: Experiences of HIV in Zimbabwe. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 15(5), 583–597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2013.776111

- Omonaiye, O., Kusljic, S., Nicholson, P., & Manias, E. (2018). Medication adherence in pregnant women with human immunodeficiency virus receiving antiretroviral therapy in sub- Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 805–825. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5651-y

- Patel, R., Ratner, J., Gore-felton, C., Kadzirange, G., Katzenstein, D., Patel, R., Ratner, J., Gore-Felton, C., Kadzirange, G., Woelk, G., & Katzenstein, D. (2012). HIV disclosure patterns, predictors, and psychosocial correlates among HIV positive women in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care, 24(3), 358–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2011.608786

- Preau, M., Beaulieu-pr, D., Henry, E., Bernier, A., Pr, M., Veillette-bourbeau, L., & Otis, J. (2015). HIV serostatus disclosure: Development and validation of indicators considering target and modality. Results from a community-based research in 5 countries. Social Science & Medicine, 146(1), 137–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.034

- Rodriguez, V. J., Mandell, L. N., Babayigit, S., Manohar, R. R., Weiss, S. M., & Jones, D. L. (2018). Correlates of suicidal ideation during pregnancy and postpartum Among women living with HIV in Rural South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 22(10), 3188–3197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2153-y

- Shamu, S., Zarowsky, C., Shefer, T., Temmerman, M., & Abrahams, N. (2014). Intimate partner violence after Disclosure of HIV test results among pregnant women in Harare, Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE, 9(10), 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109447

- Simbayi, L. C., Zungu, N., & Evans, M. (2017). HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among sexually active people living with HIV in South Africa: Results from the 2012 national population-based household survey. AIDS and Behavior, 21(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1278-5

- Spangler, S. A., Abuogi, L. L., Akama, E., Bukusi, E. A., Musoke, P., Nalwa, W. Z., Odeny, T. A., Onono, M., Wanga, I., & Turan, J. M. (2018). From ‘half-dead to being ‘free’: Resistance to HIV stigma, self-disclosure and support for PMTCT / HIV care among couples living with HIV in Kenya. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 20(5), 489–503. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1359338

- Ssali, S., Atuyambe, L., Tumwine, C., Segujja, E., Nekesa, N., Nannugi, A., Ryan, G., & Wagner, G. (2010). Reasons for disclosure of HIV status by people living with HIV/AIDS and in HIV Care in Uganda: An exploratory study. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 24(10), 675–681. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2010.0062

- Stinson, K., & Myer, L. (2012). Barriers to initiating antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy: A qualitative study of women attending services in Cape Town, South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research, 11(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2012.671263

- Tam, M., Amzel, A., & Phelps, B. R. (2015). Disclosure of HIV serostatus among pregnant and postpartum women in sub-Saharan Africa : a systematic review. AIDS Care, 27(4), 436–450. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2014.997662

- Tarwirey, F. (2005). Stigma and discrimination: Coping behaviours of people living with HIV and AIDS in an urban community of Mabvuku and Tafara, Harare, Zimbabwe. Central African Journal of Medicine, 51(7), 71–75.

- Tesfaye, S., & Bune, G. (2014). Generalized psychological distress among HIV- infected patients enrolled in antiretroviral treatment in Dilla University Hospital, Gedeo Zone, Ethiopia. Global Health Action, 7(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23882

- Trinh, T. T., Yatich, N., Ngomoa, R., Mcgrath, C. J., Richardson, A., Sakr, S. R., Langat, A., John-Stewart, G. C., Chung, M. H., & Shankar, E. M. (2016). Partner disclosure and early CD4 response among HIV-infected adults initiating antiretroviral treatment in Nairobi Kenya. PLoS ONE, 1(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163594

- Tshweneagae, G. T., Oss, V. M., Mgutshini, T., Africa, S., Tshweneagae, G., Africa, S., & Attribution, C. (2015). Disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners by people living with HIV. Curationis, 38(1), 1174–1180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v38i1.1174

- Tumwine, J. K., Rujumba, J., Neema, S., Byamugisha, R., Tylleska, T., & Heggenhougen, H. K. (2012). ‘“Telling my husband I have HIV is too heavy to come out of my mouth”’: Pregnant women’s disclosure experiences and support needs following antenatal HIV testing in eastern Uganda. Journal of International AIDS Society, 15(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.15.2.17429

- Udigwe, G. O., Mbachu, I. I., & Oguaka, V. N. (2013). Pattern and predictors of partner disclosure of HIV status among HIV positive pregnant women in Nnewi Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Medicine, 22(4), 336–340.

- UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2000). Opening up the HIV/AIDS epidemic disclosure, ethical partner counselling.

- Vu, L., Andrinopoulos, K., Kendall, C., & Eisele, T. P. (2012). Disclosure of HIV status to sex partners among HIV-infected men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 16(1), 132–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9873-y

- Wong, L. H., Van Rooyen, H., Modiba, P., Richter, L., Gray, G., Sa, F., McIntyre, J. A., Schetter, C. D., & Coates, T. (2009). Test and tell: Correlates and consequences of testing and disclosure of HIV status in South Africa (HPTN 043 Project accept). Epidemiology and Social Science, 50(2), 12–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181900172

Appendices

Appendix 1

Round 3

Round 4

Round 5

Appendix 2