ABSTRACT

Achieving the 95-95-95 UNAIDS targets requires meeting the needs of adolescents, however we lack evidenced-based approaches to improving adolescent adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), increasing viral suppression, and supporting general wellbeing. We developed Family Connections as a group intervention for adolescents and their adult caregivers and conducted a randomized controlled trial in Ndola, Zambia to test feasibility and acceptability. Fifty pairs (n = 100) of adolescents (15–19 years and on ART ≥ 6 months) and their caregivers were randomly assigned either to the intervention consisting of 10 group sessions over 6 months, or to a comparison group, which received the usual care. Each pair completed baseline and endline surveys, with adolescents also undergoing viral load testing. Of the 24-intervention adolescent/caregiver pairs, 88% attended at least eight group sessions. Most adolescents (96%) and all caregivers would recommend Family Connections to peers. Adolescent viral failure decreased but did not significantly differ by study group. Adolescents in the intervention group showed a greater reduction in HIV-related feelings of worthlessness and shame than the comparison group. The feasibility, acceptability, and the positive trend toward significantly reducing internalized stigma, generated by this Family Connections pilot study, contributes valuable data to support adolescent/caregiver approaches that use peer groups.

Introduction

The needs of adolescents must be met to achieve the 95-95-95 UNAIDS targets. We lack evidenced-based approaches to improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), increasing viral suppression, and supporting the overall health and wellbeing of adolescents living with HIV (ALHIV) (MacPherson et al., Citation2015; Reif et al., Citation2020; Ridgeway et al., Citation2018). Programs that do exist for ALHIV, such as the VUKA program in South Africa (Bhana et al., Citation2010), Families Matter in Kenya (Poulsen et al., Citation2010), and Community Adolescent Treatment Supports in Zimbabwe (Willis et al., Citation2019) focus on adolescents and children below the age of 15, and those that include older adolescents rarely involve their caregivers and families (Lightfoot et al., Citation2007; Parker et al., Citation2013).

Family processes influence young people’s HIV prevention and sexual and reproductive health behaviors (Brown et al., Citation2000; Pequegnat & Szapocznik, Citation2000; Pequegnat W, Citation2011; Perrino et al., Citation2000; Richter et al., Citation2010; Rotheram-Borus et al., Citation2011) through family communication, positive parent–child relationships, and parental monitoring (Perrino et al., Citation2000; Tinsley et al., Citation2004). Data from sub-Saharan Africa have also shown how family participation in ALHIV care can result in better health outcomes (Lowenthal et al., Citation2015). Our research from Zambia found that caregivers rarely disclose a youth’s HIV status outside the home, programs for older ALHIV emphasize individual and peers without family or caregiver involvement, and few clinic staff discussed the adolescent’s HIV care with an adult from their home (Denison et al., Citation2015; FHI360, Citation2013a). Thus, caregivers are isolated from community and clinic resources as they struggle to support their adolescents’ transition into adulthood. We also found that ALHIV had concerns about being different; 58% worried that their friends would no longer talk with them if they disclosed their HIV status and 54% reported internalized stigma – feeling of worthless, shame or guilt because they are HIV-positive (Denison et al., Citation2018; FHI360, Citation2013a). Almost all (93%) ALHIV said they wanted to attend group sessions with HIV-positive peers and 87% wanted caregiver group sessions to learn how to be a supportive caregiver (FHI360, Citation2013a). There are no data available, however, on the feasibility and acceptability of an adolescent/caregiver group approach for older ALHIV.

We developed Family Connections as a group intervention for ALHIV and their adult caregivers. Drawing upon positive youth development (Alvarado et al., Citation2017; Lerner et al., Citation2006; Lerner et al., Citation2009) and social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1991, Citation2001), Family Connections is designed to improved HIV-related health outcomes by reducing social isolation and stigma and providing accurate information in a context of peer and adult support. The primary purpose of this paper is to present the feasibility and acceptability results of the Family Connections pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) to determine if adolescents would invite, and caregivers would attend, group sessions twice a month over 5–6 months.

Methods

Study design and data collection

From April to December 2016, we conducted an RCT among ALHIV/caregiver pairs in two HIV clinics located in Ndola, Zambia. Eligible adolescents were between 15 and 19 years old, aware of their HIV status, and had been on ART for at least six months. Caregivers were nominated by the adolescents and were at least 20 years old, knew the adolescent was on ART and was someone who helps them with their HIV care. In addition, both adolescents and caregivers had to live within a 30-min drive from the study clinic, have no plans to move out of the area in the next six months, be willing to attend 10 group sessions over approximately five months, and be able to speak either Bemba or English.

We consecutively recruited ALHIV at the study clinics and asked them to return with a caregiver to enroll in the study. At enrollment, the adolescent and caregiver were consented and interviewed separately using tablets with audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) software (Questionnaire Design Studio 2.6.1). Survey questions appeared on the tablet screen in English with audio in Bemba. After they completed the baseline survey, the pairs were randomized to the intervention or comparison group using pre-labelled opaque envelopes randomly sequenced and numbered. Randomization sequences were generated using permuted blocks stratified by clinic for a 1:1 ratio between the intervention and control groups. Enrollment numbers per strata by sex were not pre-specified and extra envelopes were generated for each sex as HIV clinics serve more females than males. This process resulted in one extra pair being assigned to the control group at the time recruitment was completed.

Medication electronic monitoring system (MEMS) cap and bottle (Aardex, Switzerland) data were collected monthly to measure adolescents’ ART adherence by tracking the date and time the bottle is opened. Viral load was measured at baseline and endline using a CAP/CTM HIV-1 test version 2.0. We also collected medical chart data such as ART start date, pre-ART CD4 cell count and pre-ART World Health Organization (WHO) stage. Both adolescents and caregivers completed an endline survey using ACASI.

The study team used human-centred design principles of engaging users in all aspects of intervention design and adaptation (Design for Health), including sharing and discussing study findings in small groups during dissemination activities. This process generated feedback on participants’ experiences with Family Connections and their recommendations to refine the intervention. The trial was registered retrospectively at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04442399).

Family Connections: intervention arm

The intervention was based on the WHO-endorsed manual entitled Positive Connections: Leading Information and Support Groups for Adolescents Living with HIV, designed for adults to lead information and support groups for ALHIV in resource-poor settings (FHI360, Citation2013b). We developed a caregiver companion guide to create Family Connections. Healthcare providers at each clinic underwent a weeklong training and facilitated the 10 sessions held every other Saturday at their HIV clinic over a six-month period (). The pairs would arrive together and attended separate group sessions, sometimes participating in joint activities. After each group session, intervention participants completed a post-session survey using ACASI to assess the quality and usefulness of the session information, acceptability of the group context, and satisfaction with the facilitators. Study team members recorded intervention session attendance.

Table 1. Intervention sessions.

Comparison arm

Standard of care was offered to ALHIV in the comparison arm, which included regular clinic visits and the option of joining existing monthly youth group meetings. Adolescents met with study staff monthly to collect their MEMs adherence data. Caregivers in the comparison arm completed baseline and endline surveys only.

Analysis and measures

Primary outcomes

Feasibility: Our a-priori definition of feasibility was having at least two-thirds of the pairs attending 80% or more of the intervention sessions based on attendance logs.

Acceptability: We computed the proportion of participants who reported during the endline survey that they would recommend Family Connections to others. We also computed the proportion who felt the sessions helped them (adolescents) or gave them skills to support their adolescent (caregivers) to take their ART daily, cope with stigma, and have safer sex.

Secondary outcomes

In addition to the primary measures, we summarized the post-session survey responses. This study was not powered to test the impact on HIV-related outcomes, however, we explored differences between groups in terms of ART adherence, viral failure, and internalized stigma.

ART adherence: We analyzed ART adherence MEMS caps data. We generated one observation per day per participant over 6 months indicating if the youth took the full dosage prescribed with a binary variable. Each participant’s average daily adherence was determined by taking the mean of the observations. If a participant reported not using MEMs caps on certain days (e.g., travelled with pills but without the MEMS bottle), those dates were not included in the determination. We then performed a t-test to compare the mean average daily adherence between the two study arms.

Viral failure: Defined as having 1,000 or more RNA copies per mL, we created a dichotomous variable of viral failure (≥1,000 copies/mL) versus not viral failure (<1,000 copies/mL). We compared changes in the proportion of adolescents with viral failure between groups using a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model with a logit link, accounting for repeated within subject measures.

Adolescent internalized stigma: We used three agree/disagree statements from the Internalized AIDS Stigma Scale (IA-RSS) as adapted previously in Zambia (Denison et al., Citation2018) that measures if you feel guilty, ashamed or worthless because you are HIV positive (Kalichman et al., Citation2009). Using baseline ALHIV data, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.55, so each of the three items were examined as separate indicators comparing baseline to endline changes between study groups, using similar GEE models as described above.

Ethical considerations

This study was reviewed and approved by the Eres Converge Institutional Review Board in Zambia, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board, FHI 360’s Protection of Human Subjects Committee, and the Zambia Ministry of Health. We obtained written consent. Adolescents ages 15–17 gave assent and their parent or guardian provided parental permission. Participants received 75 Kwacha (about US$8) for study-related time and travel and 25 Kwacha at the end of the study (about US$3) if they returned their MEMS cap. Intervention participants were provided lunch and snacks.

Results

Participants

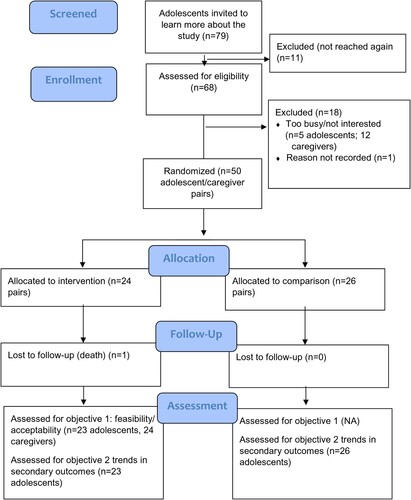

A total of 79 potentially eligible adolescents were invited to learn more about the study (). Of these 79,11 were unreachable after initial contact. Out of the remaining 68 potentially eligible adolescents, five were too busy or not interested in participating, 12 had caregivers who were too busy or not interested, and the reason for declining was not recorded for one. In total, 50 adolescent and caregiver pairs (100 individuals) were enrolled in the study between April 30 and May 20, 2016.

More than half of participants were female (62%), had completed primary school (74%) () and were on average 17 years of age. Sixty-two percent self-reported acquiring HIV from their parents. Most adolescents (66%) had been on ART for three or more years.

Table 2. Baseline socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of adolescent and caregiver participants.

The average age of caregivers was 45 years and 76% were female. More than half of caregivers were mothers or aunts (56%); fathers accounted for only 12%. Three-quarters of caregivers had known their adolescent since the youth’s birth, but less than half had lived with the adolescent for the youth’s entire life. Ninety percent had ever attended school and 40% worked outside the home. Most caregivers reported knowing their HIV status (82%), with 42% self-reporting that they were HIV-positive.

Intervention feasibility and acceptability

Out of 24 adolescent/caregiver pairs assigned to the intervention group, 87.5% attended eight or more of the 10 intervention sessions together (). Adolescents who did not attend intervention sessions reported feeling sick, being out of town, or attending other events (i.e., church, school). Reasons caregivers did not attend intervention sessions were because of work, attending other events, caring for someone who was sick (mainly the enrolled adolescent) or being out of town (data not shown). Some caregivers, after enrolling in the study, found they could no longer attend the intervention. In these cases, the original caregiver would have a proxy family member attend on his or her behalf. Five proxy caregivers for four different youth attended a total of 14 sessions during the intervention.

Table 3. Intervention feasibility and acceptability.

All adolescents except one (95.7%) reported that they would recommend the intervention to another ALHIV and that the intervention helped them take their ART daily and gave them the skills to cope with stigma and to have safer sex (). All caregivers reported they would recommend the intervention to another caregiver of an ALHIV. Most caregivers (91.7%) felt that the intervention helped them support their adolescent take their ART daily, gave them skills to cope with stigma, and 87.5% reported that the intervention helped them talk about sex with their adolescent. About two-thirds of adolescents and most of the caregivers (83.3%) thought the duration of approximately six months was just right, with only one caregiver participant reporting that six months was too long. Most adolescents and caregivers (87%) reported that the frequency of meeting twice a month was just right.

Secondary outcomes

Post-session survey responses

The 24 adolescents who attended the intervention sessions completed 204 post-session surveys (). Another 26 caregivers (including three proxy caregivers) completed 200 post-session surveys. Adolescent and caregiver responses to the post-session questions were similar across clinics unless otherwise noted below. On average, more than 95% of adolescents and caregivers found the group context acceptable, and they felt that the information shared was generally clear. About one-third of participants also said that the information they received in sessions was completely new, especially for topics on stigma and discrimination, communication, and sexual health and positive prevention (data not shown).

Most participants on average (95%) reported that facilitators listened carefully, and that everyone had an opportunity to talk. When asked if the facilitator was not judgemental, on average most participants agreed across sessions (82% of adolescents; 79% of caregivers). ALHIV reported more facilitator judgement in the sessions on sex and positive prevention (data not shown). Among caregivers, some reported facilitator judgement on the nutrition session (70%), and in one site, on the sessions on disclosure, communication, and handling discrimination (67%).

HIV-related outcomes

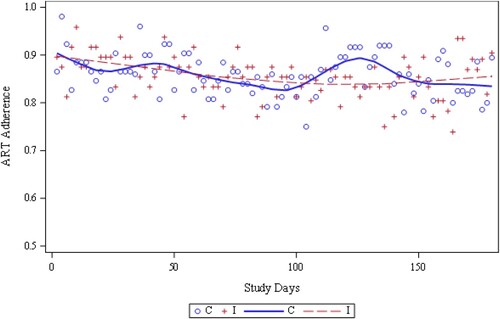

For adolescents, the mean ART adherence (86%) did not differ by study group (, ).

Figure 2. ART Adherence throughout the study period of 180 days (two-day averages).

Note: The proportion of adolescents who took 100% of their ART was computed for each study day and averaged over every two days for smoothing purposes.

Table 4. Trends in secondary outcomes among adolescents.

Adolescent viral failure decreased but the changes did not significantly differ by group (I: 38% to 30% vs. C: 28% to 23%, p = 0.97) (). We observed a trend towards a greater reduction in HIV-related feelings of worthlessness (I: 54% to 22% vs. C:38% to 35%, p = 0.06) and shame (I: 58% to 30% vs. C:54% to 58%, p = 0.07) in the intervention group as compared to the comparison group, but this change did not reach statistical significance.

Discussion

Family Connections is an acceptable and feasible adolescent/caregiver group intervention. We have demonstrated the willingness of older ALHIV and their caregivers to attend a joint program with other families offering a concrete strategy that moves beyond the individual focus of most HIV clinics. This pilot data reinforced the importance of the Family Connections content with one-third of participants learning completely new information. Almost all participants also reported having learned skills related to ART adherence, coping with stigma and having safer sex. These are critical skills adolescents need to develop, and caregivers need to support, as youth transition into adulthood (Mburu et al., Citation2013; McCarraher et al., Citation2018).

Family Connections also showed a promising reduction in internalized stigma. At baseline around half of the adolescents felt ashamed or worthless because of their HIV status. These are strong emotions during a phase in life when adolescents are “developing and consolidating their sense of self” (WHO, Citation2014). An emerging body of literature is exploring identity among adolescents with chronic illness diagnoses and how developmental stage and abilities (e.g., cognitive processes) may affect and be influenced by self-identity (Kirk & Hinton, Citation2019; Monaghan & Gabe, Citation2018; Pantelic et al., Citation2019; Wicks et al., Citation2019). At the same time, all forms of stigma (e.g., perceived, experienced) are recognized as factors that impede many desired HIV-related health behaviors and outcomes (Denison et al., Citation2015, Citation2018; Sengupta et al., Citation2011). Despite the potential importance of stigma, few interventions exist to address internalized stigma among ALHIV. For example, a systematic review of stigma-reduction interventions in low- and middle-income countries found only one study that focused solely on youth (Pantelic et al., Citation2019; Rongkavilit et al., Citation2015). While not reaching statistical significance, the large reduction in internalized stigma experienced by the Family Connections recipients indicate a potential pathway for addressing adolescent HIV-clinical outcomes and should be tested further.

Another key finding in this study is the participants’ reports of how providers handled session topics, with most participants reporting a non-judgmental approach. A marked deviation from this overall assessment were the sessions on sexual and reproductive health where only 78% of adolescent participants reported that the provider was non-judgmental. Cultural and sometimes religious norms restrict discussions of sexual and reproductive health, particularly for unmarried youth (McCarraher et al., Citation2018). These data illustrate the need to directly discuss norms and values in the health care provider training that may influence delivery of non-judgmental, factual sexual and reproductive health information. Similarly, only 70% of caregivers reported the provider was non-judgmental in the sessions on nutrition and disclosure. During the dissemination meeting caregivers discussed in small groups how some topics, including nutrition and HIV status disclosure, were sensitive. This critical feedback will be incorporated into future facilitator trainings for Family Connections.

Limitations and strengths

The individual randomization of participants within the two clinics led to cross-contamination, the extent of which was not measured. During dissemination activities, some of the caregivers informed the study team that they were sharing information with caregivers in the comparison group. The comparison group members also felt they were in an intervention that they named the “MEMS program” and adolescents would compete monthly to achieve good adherence levels. This may have impacted their viral status.

Also, about one-fifth of youth eligible to enroll did not have a caregiver interested or able to participate. While we achieved high levels of participation and retention among those adolescent/caregiver pairs who did enroll, an adolescent/caregiver approach may not be feasible for all ALHIV. This fact highlights the need to explore the Family Connections approaches outside of the clinic setting to make it more accessible. This finding also indicates that while Family Connections is feasible with engaged caregivers, we need to explore ways to incorporate adult presence and role modelling, as described in positive youth development (Alvarado et al., Citation2017; Lerner et al., Citation2006; Lerner et al., Citation2009) for adolescents whose caregivers may not be able to or may not wish to participate in Family Connections.

A strength of this study was youth and caregiver engagement during the formative research processes that defined the Family Connections intervention and during the dissemination that supported the interpretation of the findings and further ways to refine the intervention. Family Connections also achieved extremely high levels of retention and successfully worked with proxy caregivers when the originally enrolled caregiver was no longer able to attend meetings. Family and work opportunities may change over the course of a six-month program and sending a proxy caregiver indicates the importance of the program to the initially enrolled caregiver and the youth’s family. As youth may have multiple caregivers and their ability to attend a program may change, an adolescent/caregiver approach needs to be flexible to maintain continuity and involvement of caring adults in these young people’s lives.

Conclusions

ALHIV need effective interventions to support their healthy transition into adulthood and to self-manage their HIV. We found Family Connections to be acceptable and feasible to adolescents and their caregivers and recommend that it is further evaluated for impact in a randomized controlled trial at a facility level to mitigate contamination and to account for facility related effects.

Geolocation information

This study was conducted in Ndola, Zambia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

We did not obtain assent/consent from participants to make their data available to a third party, therefore we are not able to make the data publicly available. Rather our consent forms specified the following “the study research team will have access to your data. This team includes the study investigators, research assistants and data analysts. All data collected from you will be destroyed in 3 years after the end of the study”.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alvarado, G., Skinner, M., Plaut, D., Moss, C., Kapungu, C., & Reavley, N. (2017). A systematic review of positive youth development programs in low-and middle-income countries. Youth Power Learning, Making Cents International.

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

- Bhana, A., McKay, M. M., Mellins, C., Petersen, I., & Bell, C. (2010). Family-based HIV prevention and intervention services for youth living in poverty-affected contexts: The CHAMP model of collaborative, evidence-informed programme development. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 13(Suppl 2), S8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2652-13-S2-S8

- Brown, L. K., Lourie, K. J., & Pao, M. (2000). Children and adolescents living with HIV and AIDS: A review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021963099004977

- Denison, J., Banda, H., Dennis, A., Packer, C., Nyambe, N., Stalter, R., Mwansa, J., Katayamoyo, P., & McCarraher, D. (2015). “The sky is the limit”: Adhering to antiretroviral therapy and HIV self-management from the perspectives of adolescents living with HIV and their adult caregivers. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18(1), 19358. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.18.1.19358

- Denison, J., Packer, C., Stalter, R., Banda, H., Mercer, S., Nyambe, N., Katayamoyo, P., Mwansa, J., & McCarraher, D. (2018). Factors related to incomplete adherence to antiretroviral therapy among adolescents attending three HIV clinics in the Copperbelt, Zambia. AIDS and Behavior, 22(3), 996–1005. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1944-x

- Design for Health. Design for health: Glossary of design terms. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and USAID Center for Innovation and Impact. Retrieved January 12, 2021 from https://www.designforhealth.org/resources/glossary-of-design-terms

- FHI360. (2013a). Adolescents living with HIV in Zambia: An examination of HIV care and treatment and family planning. Retrieved June 23, from https://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/zambia-adolescents-living-hiv-integration-family-planning.pdf

- FHI360. (2013b). Positive Connections: Leading information and support groups for adolescents living with HIV. Retrieved September 1, from https://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/positive-connections-2013.pdf

- Kalichman, S. C., Simbayi, L. C., Cloete, A., Mthembu, P. P., Mkhonta, R. N., & Ginindza, T. (2009). Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: The internalized AIDS-related stigma scale. AIDS Care, 21(1), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120802032627

- Kirk, S., & Hinton, D. (2019). “I’m not what I used to be”: A qualitative study exploring how young people experience being diagnosed with a chronic illness. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45(2), 216–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12638

- Lerner, R. M., Abo-Zena, M., Bebiroglu, N., Brittian, A., & Lynch, A. (2009). Positive youth development. In S. J. DiClemente R, R. Crosby, & J. Bass (Eds.), Adolescent health: Understanding and preventing risk behaviors (pp. 115–128). Wiley.

- Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Almerigi, J., Theokas, C., Phelps, E., Naudeau, S., & Von Eye, A. (2006). Towards a new vision and vocabulary about adolescence: Theoretical, empirical, and applied bases of a “positive youth development” perspective. In L. Balter & C. S. Tamis-LeMonda (Eds.). Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues (pp. 445–469). Psychology Press.

- Lightfoot, M. A., Kasirye, R., Comulada, W. S., & Rotheram-Borus, M. J. (2007). Efficacy of a culturally adapted intervention for youth living with HIV in Uganda. Prevention Science, 8(4), 271–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-007-0074-5

- Lowenthal, E. D., Marukutira, T., Tshume, O., Chapman, J., Nachega, J. B., Anabwani, G., & Gross, R. (2015). Parental absence from clinic predicts human immunodeficiency virus treatment failure in adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(5), 498–500. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3785

- MacPherson, P., Munthali, C., Ferguson, J., Armstrong, A., Kranzer, K., Ferrand, R. A., & Ross, D. A. (2015). Service delivery interventions to improve adolescents’ linkage, retention and adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV care. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 20(8), 1015–1032. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12517

- Mburu, G., Hodgson, I., Teltschik, A., Ram, M., Haamujompa, C., Bajpai, D., & Mutali, B. (2013). Rights-based services for adolescents living with HIV: Adolescent self-efficacy and implications for health systems in Zambia. Reproductive Health Matters, 21(41), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41701-9

- McCarraher, D. R., Packer, C., Mercer, S., Dennis, A., Banda, H., Nyambe, N., Stalter, R. M., Mwansa, J. K., Katayamoyo, P., & Denison, J. A. (2018). Adolescents living with HIV in the Copperbelt province of Zambia: Their reproductive health needs and experiences. PLoS One, 13(6), e0197853. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197853

- Monaghan, L. F., & Gabe, J. (2018). Managing stigma: Young people, asthma, and the politics of chronic illness. Qualitative Health Research, 29(13), 1877–1889. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318808521.

- Pantelic, M., Steinert, J. I., Park, J., Mellors, S., & Murau, F. (2019). “Management of a spoiled identity”: Systematic review of interventions to address self-stigma among people living with and affected by HIV. BMJ Global Health, 4(2), e001285. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001285

- Parker, L., Maman, S., Pettifor, A., Chalachala, J. L., Edmonds, A., Golin, C. E., Moracco, K., & Behets, F. (2013). Adaptation of a U.S. evidence-based positive prevention intervention for youth living with HIV/AIDS in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Evaluation and Program Planning, 36(1), 124–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.09.002

- Pequegnat, W., & Szapocznik, J. (2000). Working with families in the era of HIV/AIDS. Sage.

- Pequegnat W, B. C. (2011). Family and HIV/AIDS: Cultural and contextual issues in prevention and treatment. Springer.

- Perrino, T., González-Soldevilla, A., Pantin, H., & Szapocznik, J. (2000). The role of families in adolescent HIV prevention: A review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 3(2), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009571518900

- Poulsen, M. N., Vandenhoudt, H., Wyckoff, S. C., Obong’o, C. O., Ochura, J., Njika, G., Otwoma, N. J., & Miller, K. S. (2010). Cultural adaptation of a U.S. evidence-based parenting intervention for rural western Kenya: From parents matter! To families matter!. AIDS Education and Prevention, 22(4), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2010.22.4.273

- Reif, L. K., Abrams, E. J., Arpadi, S., Elul, B., McNairy, M. L., Fitzgerald, D. W., & Kuhn, L. (2020). Interventions to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among adolescents and youth in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review 2015–2019. AIDS and Behavior, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02822-4

- Richter, L., Beyrer, C., Kippax, S., & Heidari, S. (2010). Visioning services for children affected by HIV and AIDS through a family lens. BioMed Central.

- Ridgeway, K., Dulli, L. S., Murray, K. R., Silverstein, H., Dal Santo, L., Olsen, P., de Mora, D. D., & McCarraher, D. R. (2018). Interventions to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among adolescents in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189770

- Rongkavilit, C., Wang, B., Naar-King, S., Bunupuradah, T., Parsons, J. T., Panthong, A., Koken, J. A., Saengcharnchai, P., & Phanuphak, P. (2015). Motivational interviewing targeting risky sex in HIV-positive young Thai men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(2), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0274-6

- Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Swendeman, D., Lee, S.-J., Li, L., Amani, B., & Nartey, M. (2011). Interventions for families affected by HIV. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 1(2), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-011-0043-1

- Sengupta, S., Banks, B., Jonas, D., Miles, M. S., & Smith, G. C. (2011). HIV interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 15(6), 1075–1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9847-0

- Tinsley, B. J., Lees, N. B., & Sumartojo, E. (2004). Child and adolescent HIV risk: Familial and cultural perspectives. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(1), 208. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.208

- WHO. (2014). Health for the world’s adolescents: A second chance in the second decade. Retrieved June 23, from http://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section2/page5/adolescence-psychological-and-social-changes.html

- Wicks, S., Berger, Z., & Camic, P. M. (2019). It’s how I am … it’s what I am … it’s a part of who I am: A narrative exploration of the impact of adolescent-onset chronic illness on identity formation in young people. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104518818868

- Willis, N., Milanzi, A., Mawodzeke, M., Dziwa, C., Armstrong, A., Yekeye, I., Mtshali, P., & James, V. (2019). Effectiveness of community adolescent treatment supporters (CATS) interventions in improving linkage and retention in care, adherence to ART and psychosocial well-being: A randomised trial among adolescents living with HIV in rural Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6447-4