ABSTRACT

Malawi has one of the highest HIV prevalence rates (8.9%), and data suggest 27% pain prevalence among adolescents living with HIV (ALHIV) in Malawi. Pain among ALHIV is often under-reported and pain management is suboptimal. We aimed to explore stakeholders’ perspectives and experiences on pain self-management for ALHIV and chronic pain in Malawi. We conducted cross-sectional in-depth qualitative interviews with adolescents/caregiver dyads and healthcare professionals working in HIV clinics. Data were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and translated (where applicable) then imported into NVivo version 12 software for framework analysis. We identified three main themes: (1) Experiencing “total pain”: adolescents experienced physical, psychosocial, and spiritual pain which impacted their daily life activities. (2) Current self-management approaches: participants prefer group-based self-management approaches facilitated by healthcare professionals or peers at the clinic focussing on self-management of physical, psychosocial, and spiritual pain. (3) Current pain strategies: participants used prescribed drugs, traditional medicine, and non-pharmacological interventions, such as exercises to manage pain. A person-centred care approach to self-management of chronic pain among ALHIV is needed to mitigate the impact of pain on their daily activities. There is a need to integrate self-management approaches within the existing structures such as teen clubs in primary care.

Introduction

Global estimates show that young people aged 15–24-year-olds account for 27% of all new HIV infections (460,000/1,700,000) (UNICEF Data Dashboard, Citation2020). Malawi has one of the highest HIV prevalence rates in sub-Saharan Africa, with 9.2% of the adult population (aged 15–49) living with HIV (UNAIDS, Citation2020). In 2019, new HIV infections, among young people aged 15–24, accounted for 36% of all new HIV infections (12000/33000) in Malawi.

Evidence suggests that young people have poorer HIV treatment outcomes than adults, as they are more likely to be lost to follow up and less likely to be virally suppressed (Evans et al., Citation2013). Adolescence is an important time to lay foundations of good health and to self-manage chronic, in particular those with HIV. WHO argues that adolescents must participate in planning, monitoring and evaluating programmes relevant to them, not simply to be passive beneficiaries (WHO, Citation2014).

The Malawi HIV Impact Assessment shows a prevalence of 1.5% (2% females and 0.9% males) among 15–19-year-olds (Malawi Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment, Citation2016). A cross-sectional study of young people with HIV (aged four months to 16 years) referred to a palliative care clinic in Malawi reported that 27% experienced pain in the previous week (Lavy, Citation2007). Pain among adolescents is often undertreated, underreported, and unlikely to be routinely assessed (Robbins et al., Citation2013).

Pain and symptoms are associated with HIV infection due to the opportunistic infections and effects of treatment (Kourrouski & Lima, Citation2009), and are experienced throughout the disease trajectory (Peltzer & Phaswana-Mafuya, Citation2008). Pain and symptoms, among people living with HIV, have negative associations of both clinical and public health importance. Pain is associated with poor antiretroviral drug adherence (Harding et al., Citation2010; Hughes et al., Citation2004b; Sherr et al., Citation2008), and quality of life (Brechtl et al., Citation2001; Harding et al., Citation2012a; Holzemer et al., Citation2001; Hughes et al., Citation2004a), viral load rebound (Lampe et al., Citation2010), psychological distress (Marcus et al., Citation2000; Rosenfeld et al., Citation1996; Vogl et al., Citation1999), alcohol use, and intravenous drug use (Parker et al., Citation2014), psychiatric illness (Vranda & Mothi, Citation2013), sexual risk taking (Harding et al., Citation2012b), and suicidal ideation (Simms et al., Citation2011).

Patients spend only a few hours with medical personnel; most of their daily life is spent alone self-monitoring their condition, or with their family members (caregivers) who monitor the condition of the patient. Self-management interventions are thus a better strategy for improving patients’ outcomes (Mcgowan, Citation2012). Self-management intervention “includes the actions individuals take for themselves, their children and families to stay fit and maintain good physical and mental health, meet social and psychological needs and prevent illness and accidents, care for minor ailments and long-term conditions, and maintain health and well-being after an acute illness or discharge from hospital” (Department of Health, Citation2013).

HIV/AIDS is now managed using a chronic care model (Mitchell & Linsk, Citation2004; Schmitt & Stuckey, Citation2004), with the majority of care is offered outside formal health facilities (Swendeman et al., Citation2009). For adolescents, self-management support aims to assist and sustain the adolescent and their caregivers within their own life patterns and goals (Bodenheimer et al., Citation2002). Self-management interventions increase self-efficacy for self-care skills, enhance knowledge of management of chronic conditions, and improve communication between patients/carer and providers across various disease conditions (Lorig et al., Citation2006).

Our previous work among adults with HIV in Malawi showed that a brief pain self-management intervention reduced-intensity pain (Nkhoma et al., Citation2013; Nkhoma et al., Citation2015). The biopsychosocial model (Engel, Citation1977) guided the development of the intervention in targeting adequate and effective use of analgesia (biological), providing support and information to minimise distress associated with pain (psychological), and targeting the intervention at the level of the patient/carer dyad (social)(Nkhoma et al., Citation2013). HIV-specific pain intervention is needed as evidence suggests barriers to pain presentation and management for adults living with HIV (Baker et al., Citation2021).

It is unclear how they currently self-manage the effects of pain, and how it may be best improved. We, therefore, conducted a qualitative study to explore stakeholders’ pain self-management experiences for adolescents living with HIV (ALHIV) in Malawi and explore key components of a comprehensive and appropriate pain self-management approach that subsequently inform the design of an intervention on pain self-management. To our knowledge, this is the first study on pain self-management among ALHIV in Malawi, and the findings offer the potential to improve quality of life for ALHIV within limited health resources.

Aims and objectives

We aimed to explore stakeholders’ experiences on pain self-management practices and approaches for ALHIV in Malawi to inform future design of an intervention on pain self-management. The objectives were to identify appropriate elements of the self-management approaches from the perspective of ALHIV, their families/caregivers, and health professionals and to describe the acceptable model of self-management of pain suitable for ALHIV and their families.

Methods

Study design

We conducted cross-sectional qualitative in-depth interviews with adolescents, family caregivers, and health professionals.

Study participants

Participants were “patient-caregiver dyads” (i.e., ALHIV and their family primary caregivers) and health professionals working with ALHIV in primary care.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for adolescents

Inclusion criteria were adolescents were aged between 10 and 17 years, aware of their diagnosis and attending an HIV primary care clinic. This was based on WHO definition of “adolescents” as individuals in the 10–19 years age group (World Health Organisation, Citation2014). We did not include those who were at least 18 years of age because our previous research already established models of self-management of pain among adults living with HIV in Malawi (Nkhoma et al., Citation2015). Adolescents were able to provide informed assent, including the ability to communicate in English or Chichewa (the local language in Malawi). Furthermore, we recruited adolescents, who were experiencing chronic pain for at least three months, in line with Merlin’s definition of chronic pain defined as a constantly and persistently occurring phenomenon despite treatment or medication (Merlin et al., Citation2013; Merlin et al., Citation2014), beyond the period of normal tissue healing (three months) and may be more related to nervous system changes than to actual tissue injury (Chou et al., Citation2009; International Association for the Study of Pain, Citation1986).

We excluded adolescents who were housebound and unable to attend primary care, those less than 10 years and above 17 years of age, those who were not aware of their HIV status, and those with acute pain.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for caregivers

Primary caregivers were identified by the patient, and were involved in daily provision of care to ALHIV in line with the definition of caregiver “unpaid, informal providers of one or more physical, social, practical and emotional tasks. In terms of their relationship to the patient, they may be a sibling, parent, aunt, uncle or other blood or non-blood relative”(Harding, Citation2013). Caregivers were at least 18 years of age, able to give informed consent and parental consent for the adolescent participant must have disclosed HIV status to the adolescent participant and were able to communicate in English or Chichewa.

We excluded young caregivers less than 18 years of age and those who were not involved in caring for the adolescents on a daily basis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for health professionals

Health professionals (i.e., Nurses, clinical officers, social workers, and counsellors) with at least 6-month working experience at the HIV clinic/facility, and willing to give informed consent were included.

Setting

Participants were recruited at Lighthouse and Nathenje health centres in Lilongwe city, the central region of Malawi. Lighthouse is a specialised hospital with a primary care clinic, while Nathenje health centre is a primary health care facility.

Recruitment and ethical considerations

Potential adolescent and caregiver participants were identified and approached by clinic staff. We used the following sampling frame: experience of pain for at least three months, age, knowledge of HIV status, and being a primary caregiver. Clinic staff checked adolescents’ clinical records to identify potential eligible participants guided by the eligibility criteria. They then explained the study and provided information sheets to adolescents and caregivers, requesting them to contact research assistants if they would be willing to get more details and/or participate in the study. Research assistants also confirmed with the adolescents if they experienced chronic pain before proceeding with recruitment procedures. Information sheets were read aloud to the adolescent and caregiver participants.

Health care professionals were identified by the facility manager who introduced the study to them using the following sampling frame: professional cadre and period working at the facility. Potential participants were given an information sheet containing details about the study.

Potential participants thereafter communicated with research assistants who arranged a meeting to provide further details about the study and agreed on date and time to conduct the interview for willing participants.

Informed assent and consent were obtained from adolescents and caregivers, respectively.

For adolescents, primary consent was obtained from caregivers although the consent of the adolescent himself/herself was ultimately what informed continued participation in the study. All participants signed (or gave an ink thumb print) on the consent form. All participants were given a copy of the consent form to keep. Participants were given a drink and snack during the interview and transport reimbursements (approximately 10 USD). Ethics approval was obtained from King’s College London (HR-17/18-7122) and Malawi National Health Sciences Research Committee (18/07/2097).

Data collection

Semi-structured topic/interview guides were developed and iteratively refined. For adolescents and their families, interviews examined the perceptions of pain, tolerability, and attribution, past or current treatment for pain (pharmacological and non-pharmacological), preferred self-management interventions and outcomes in line with the biopsychosocial model (Engel, Citation1977), components, content, timing, delivery, duration, and implementation of self-management of pain. Health professional topic guides addressed usual practice, perceived patient and family needs, and optimal model of pain self-management in terms of goals, content, frequency and preferred outcomes.

Adolescents were interviewed separately from their caregivers to enable them to share information freely. All interviews were conducted within the clinic facility and audio-recorded, then uploaded into a password-protected computer kept at Kamuzu College of Nursing. Transcripts were pseudonymised.

Data analysis

Participants’ interviews were transcribed verbatim and translated into English (where necessary) before being imported into NVivo version 12 for thematic framework analysis (Gale et al., Citation2013b). This is the appropriate method to analyse qualitative data to compare within and across different groups within a study which seeks to examine prior health or policy concerns (Gale et al., Citation2013a). We developed a coding frame inductively on a subset of transcripts. KN developed an initial coding frame from patient transcripts (n = 2), caregiver transcripts (n = 2), health and professional transcripts (n = 2). This coding frame was shared with GM who also coded a similar number of transcripts. The study team reviewed the coding frame and differences were resolved through discussion. The final frame was agreed and KN coded all the remaining transcripts. A model of the coding frame was developed, with each theme and sub-themes clearly defined to ensure the internal consistency of each code. We have reported illustrative quotes for each theme, alongside study participant ID number to demonstrate reporting from across the sample breadth.

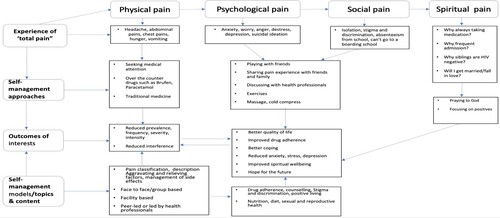

Following the framework analysis, we adopted a thematic analysis approach (Attride-Stirling, Citation2001) to generate a schematic depicting how main themes and patterns that emerged in the analysis aligned with the original questions. KN and GM developed an initial thematic network which was then adapted through iterations of feedback with the whole team. The final thematic network is presented in .

Results

Characteristics of study participants

presents the characteristics of all the study participants. We recruited n = 21 adolescents, n = 20 caregivers, and n = 22 health professionals. We recruited the same number of adolescents in terms of gender and education. Participants had an age range of 10–17 years, 52% percent were male. Participants had a mean age of 6.2 years on HIV treatment.

Table 1. Characteristics of study participants.

The majority of caregivers were female (n = 16; 80%), mostly mothers of the adolescent participants (n = 11; 55%). Most caregivers relied on farming as a source of income to support their households.

The majority of health professionals were male (n = 14; 63.6%). We recruited the number of nurses and counsellors (n = 8; 36.4% per group). Health professionals had almost 10 years of work experience and almost five years working at the facility where they were recruited.

Main findings

We identified the three main themes: (1) Experiencing physical, psychosocial, and spiritual pain: under this theme, we identified two sub-themes: pain impacting social and daily life and experiencing multiple losses. (2) Self-management approaches for pain and symptoms: under this theme, we identified seven sub-themes: understanding self-management, discussing self-management, benefits of self-management, preferred model of self-management, preferred topics and content, preferred site of delivery and preferred outcomes. (3) Current pain strategies among adolescents, we identified three sub-themes here: Discussing pain management, using drugs and traditional medicines to manage pain, and using non-pharmacological interventions to manage pain. These themes and sub-themes are further explored next. summarises these themes and highlights the overall findings of this study in line with the biopsychosocial model of pain. presents quotes supporting the themes and sub-themes.

Table 2: Summary of main themes and quotes from study participants

Experiencing physical, psychological, social, and spiritual pain

Adolescents reported experiencing elements of “total pain” that is physical, psychological, emotional, social, and existential (spiritual) suffering. They reported experiencing pain and physical symptoms such as chest pain, abdominal pains, coughing, headache, numbness, body weakness, diarrhoea, hunger, discharge from the ears, and sores in the mouth. Adolescents described pain as burning, pricking and clumping. Caregivers also echoed similar experiences (Quotes, 1,2, and3).

Some adolescents experienced psychological pain because of their HIV status, and thought that they would not enter into an intimate relationship or marry. Adolescents reported becoming depressed, worried, anxious, stressed, angry and always fearing for their lives (Quotes 4).

Health professionals attested that some adolescents were keen to understand if they will have their own family due to their HIV (Quote 5). Some had suicidal thoughts due to this distress (Quote 6).

Some adolescents reported feeling spiritual pain and did not see the purpose of living. This led some adolescents to lose hope in life. Their caregivers and health professionals also confirmed the terrible spiritual pain these young people were experiencing as they believed death was imminent (Quotes 7 and 8).

Effects of pain experience

All participants reported that experience of pain led to poor drug adherence. This was mainly due to the side effects of ART such as abdominal pain, vomiting, and peripheral neuropathy. Some adolescents, therefore, stopped taking treatment. This is common among adolescents who did not have a guardian to supervise them (such as those who lost their parents) or due to poor or lack of supervision from available guardians to monitor if they are taking drugs as prescribed (Quote 9).

Pain had effects on education following poor school attendance, absenteeism, lack of concentration, and poor performance. Some were even unable to attend boarding school because they needed supervision and monitoring by parents or close relations in taking medications, also because of fear of stigma as they did not want their friends to know that they are taking medication (Quotes 10 and 11).

Adolescents also reported feeling hunger, experiencing sleeping difficulties, and felt that life was worthless. These problems and concerns also affected their caregivers in their daily activities such as work (Quote 12).

Some health professionals reported that pain had severe negative effects among adolescents, for instance, some of them had suicidal ideation, and engagement in sex work due to unresolved psychological and physical pain. Others were engaged in drugs and alcohol abuse. These problems eventually had effects on the entire family (Quotes 13 and 14).

Caregivers were affected by adolescents’ pain. They either reported late for work or missed work shifts because they had to look after the sick child. Pain also affected siblings of the sick adolescents who were concerned because of constant illness. (Quote 15).

Pain experience among adolescents also caused negative effects among health professionals who were providing care to the adolescents (Quote 16).

Experiencing multiple losses

Adolescents reported experiencing multiple losses due to long-lasting pain. This included loss of friends and the associated playing because of limited socialisation opportunities, intellectual loss leading to lack of concentration in class, and loss of hope in life and life being worthlessness. Caregivers reported that some adolescents were called by names by their friends because they have hearing problems which eventually affected both the patient and the caregiver psychologically. Another caregiver was concerned about the hearing problem of his son in terms of his social life and education (Quotes 17 and 18).

Self-management approaches for pain and symptoms

Understanding of self-management

While most health professionals could ably define the term self-management, most adolescents and family caregivers could not describe or explain the concept. Adolescents explained it as taking care of self, managing signs and symptoms, and taking medication when in pain (Quotes 19, 20, 21).

Discussing self-management at the health facilities

It was evident from the adolescents’ accounts that self-management was rarely discussed at their care, with a few exceptions of it being discussed during teen clubs (Quote 22). Some health professionals stated that they discuss self-management with adolescents at the facility (Quote 23).

Benefits of self-management

Health professionals stated that self-management would be beneficial for them and their patients. In particular, staff felt it would assist the heavy workload that included with minor issues which could easily be managed at home with the support of family members. It could also be helpful to save transport and other costs since most of the patients live far away from the clinic. Moreover, adolescents will be able to take care of themselves at school where they are always alone without parents (Quotes 24 and 25).

Preferred mode of delivery for self-management

Some adolescents and caregivers preferred information leaflets, seminars, and group sessions to learn about self-management, with health care professionals or peers as facilitators. This was endorsed by health professionals who would prefer to facilitate group-based sessions. The majority felt they could learn better at the health facility in groups as a morale booster and to benefit from views expressed by others, particularly if the existing structures or approaches of teen club meetings could be adopted.

However, a minority of adolescents and family caregivers reported that they preferred individual face-to-face or one-to-one session delivered by health professionals (Quote 26).

Preferred topics/topics of interest

All participants mentioned that topics should focus on drug adherence, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual management of pain (Quotes 27 and 28). However, adolescents mentioned diverse topics that they preferred to be included in self-management training that were not directly linked to pain management for example nutrition/diet, social interaction, hygiene, communication skills, self-esteem, and life skills training (Quote 29). This was echoed by health professionals who want adolescents to learn about anger management, sexual relationships, reproductive health and teenage pregnancies (Quote 30).

For psychosocial pain, health professionals thought that young people should also learn about positive living, accepting their status, dealing with stigma because often they experience psychological problems (Quote 31).

Caregivers reported that they need information about how to support their children at home when they are experiencing pain (Quote 32).

Preferred site of self-management provision

Participants stated that self-management should be delivered either at the facility or at the community centre or at home. Most participants did not prefer home model because they will be seen by neighbours or other family members who don't know about the status of the adolescent being visited (Quotes 33, 34, and 35). Some caregivers preferred to receive the services at home so that they can receive the service together with the sick adolescent (Quote 36).

Preferred outcomes

For physical pain, participants wanted to experience reduced prevalence and burden of pain, pain interference with activities such as sleep, work, schooling, play, and improved drug adherence.

On psychological outcomes participants reported that they want to be free from stress, worry, anxiety and depression (Quotes 37 and 38). On social pain, adolescents reported that they want to concentrate in class and perform well during exams (Quote 39).

Current pain strategies among adolescents

Discussing pain management

While all participants experienced pain, a minority reported having discussed pain management during teen clubs with doctors and nurses. However, they were quick to indicate that whenever they get to clinics, the clinicians ask them if they have any problem and were being given medications depending on the problem presented. Some adolescents also alluded to the fact that teen clubs helped to relieve their psychological problems (Quotes 40, 41, and 42).

A caregiver reported that her daughter usually attends the clinic alone most of the time and she encourages her to discuss pain issues with health professionals (Quote 43).

Health professionals reported that in most cases they do ask about pain experience although their questions focused on the general health of the adolescents as a trigger to pain questions (Quote 44).

Using western and traditional medicines to relieve pain

The majority of adolescents reported the use of medicines obtained from health facilities or purchased from shops to relieve pain depending on the affected body part. These medicines included panadol, hedax, brufen, and aspirin for headaches, liniment for leg pains and Tumbocid for abdominal pain, piriton and topical lotions for the itching rash and pyridoxine for numbness of the legs. It was interesting that the use of traditional medicines in the form of soot (a by-product of burning fossil fuels) given by the grandmother was also reported to work in the management of pain. The minority felt that medical interventions were more effective than non-medical interventions (Quotes 45 and 46).

Using non-medical interventions

The adolescents reported several non-medical interventions for pain. These included walking, doing exercises/jogging, reading magazine, using cold water either drinking or washing the painful body part, playing or charting/talking/sharing experienced problem with friends, parents or health personnel, and watching TV (Quotes 47, 48, 49, and 50).

Discussion

ALHIV and pain report a high burden of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual pain challenges. This was reported by health professionals, caregivers, and adolescents. Pain was reported to have negative effects on their lives, interfering with their daily activities such as playing with friends, schooling, performance in class, and concentration in class. Participants also reported feelings of anger, depression, stress, and worry about the future. Some adolescents felt life is not worth living and had suicidal thoughts.

Pain also affected their family members (parents and guardians) who missed their work schedule or were unable to carry out other activities at home. This also affected other children in the family who were always anxious to see their siblings in constant pain.

In a cross-sectional study among young people who acquired HIV perinatally and HIV- children conducted in the USA and Puerto Rico, the prevalence of pain and psychiatric symptoms were evaluated. The study reported a higher prevalence of pain among HIV+ adolescents compared with their HIV− counterparts in the last two months (41% vs. 32%, p = .04), last two weeks (28% vs. 19%, p = .02), and lasting more than one week (20% vs. 11%, p = .03). Pain was also associated with worse psychological outcomes among the HIV+ cohort (Serchuck et al., Citation2010)..

In our study, adolescents missed some class sessions and were unable to concentrate during class sessions due to pain. This affected their performance in class and during examinations. This is consistent with other findings as a recent systematic review reported that HIV+ status had effects on educational attainments among adolescents. They missed classes because of medical appointments (Zinyemba et al., Citation2020). Thus, there is a need to formulate policies that adequately improve schooling outcomes.

Young people also experienced psychosocial pain related to stigma. They were unable to attend boarding school because they feared their friends will become suspicious when they see those taking ARVs and this would affect treatment adherence and ultimately the quality of life. The assertions by ALHIV in this study are consistent with evidence elsewhere including from studies in Rwanda and Nigeria that found that stigma and lack of privacy in settings like boarding schools were among key factors that negatively affected treatment adherence (Madiba & Josiah, Citation2019; Mutwa et al., Citation2013). Apart from pain, hunger was also reported to affect adolescents. This can be related to lack of food availability and due to the effects of ARVs. Food insecurity has also been reported to lead to poor drug adherence (Young et al., Citation2014). We, therefore, need interventions to address food insecurity which may improve drug adherence for ALHIV. Integrating nutrition and HIV treatment programmes, through interventions like providing nutritional support to people living with HIV, has been implemented albeit at a small scale in Malawi and not specifically targeted to ALHIV. There is, therefore, a need to integrate much broader food security interventions into HIV/AIDS treatment programmes to promote drug adherence among ALHIV.

Self-management was rarely discussed with adolescents during clinic visits. Many of them were not able to explain what the concept meant and how exactly to take care of themselves.

Inability of adolescents to define or describe or understand the term “self-management” signified that adolescents were not prepared to be independent which could be attributed to dependence syndrome and “handholding” culture and behaviours rendered even at adolescent clinics.

Self-management education among adolescents, during their clinic visits, is needed to empower young people. This will enable them to learn how to look after themselves to prevent experiencing pain or properly responding to it as it occurs. In our study adolescents and health workers cited teen clubs as an important platform to deliver a range of psychosocial support interventions for ALHIV. In Malawi, the Ministry of Health and partners have been scaling up teen clubs. Introducing education on self-management of pain as part of the package of care for teen clubs, therefore, presents an opportunity to improve the quality of life for ALHIV.

Data from this study show that ALHIV experienced “total pain”, reflecting the biopsychosocial model (Engel, Citation1977) that informed topics used to interview study participants. Although the biopsychosocial model is criticised for the weighting of contributing variables (Ghaemi, Citation2009) it is useful in a complex construct such as pain in HIV to explore appropriate and effective interventions (Nkhoma et al., Citation2015). Future design, testing and evaluation of self-management interventions should consider using person-centred care model which includes all the components of the biopsychosocial model including the spiritual aspect of care (International Alliance of Patients Organisations, Citation2007).

With respect to potential intervention design and delivery, participants reported that they are happy to have pain and self-management discussions during clinic visits and that non-pharmacological approaches are often appropriate. Participants reported that they would like to learn holistic management of pain that focuses on the management of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual pain. Effective self-management interventions for pain management among adults living with HIV may be delivered either online, face-to-face, or group-based consisting of booklet, leaflet, or manuals (Nkhoma et al., Citation2018). Our findings suggest that these approaches may also be appropriate if developed in adolescent-friendly formats. Adaptation of existing interventions offers great potential. Workshop-based psychoeducational interventions among adolescents and their families with chronic pain showed the potential to improve psychosocial outcomes (Coakley et al., Citation2018). One aspect to be noted in intervention design is that adolescents in our study wanted to avoid home activities to avoid stigma. It should also be noted that adolescents reported a desire to form intimate relationships but feared that this would not happen. They also noted that families would be highly critical of relationships. Person-centred care should ensure it supports this aspect of psychological and sexual development.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to explore views from ALHIV and chronic pain, their caregivers, and health care providers in sub-Saharan Africa. The collection of these stakeholders’ views gives important data for feasible and acceptable intervention studies. We designed the study, developed topic guides and analysed data using a well-established model of pain management in patients with chronic illness.

This work has some limitations. We relied on staff being aware of clients’ pain to enable recruitment, and the evidence suggests that awareness may be low. We also cannot generalise from Malawi to other African countries or regions. There may have been selection bias in those children with severe pain who drop out of care may not have been approached for recruitment.

Conclusion

This work presents the initial data needed to understand and better manage the dimensions of pain among adolescents with chronic pain and HIV. Through adolescents, caregivers, and health professional engagement, we identified suitable self-management interventions in terms of design, practical and contextual challenges and opportunities to optimise the potential for success.

We identified needs and preferences for self-management approaches from our participants to be taken into consideration when planning and designing feasible and appropriate self-management interventions for ALHIV. There is a need to test the effectiveness of self-management interventions for ALHIV using robust study designs. This will also inform subsequent integration, implementation, and rollout of self-management approaches in Malawi within the existing structures such as teen clubs in primary care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joe Gumulira, Richard Bwanali, Happy Chipeta, and Owen Gangata for collecting data, conducting transcription and translation of the interviews, and for ensuring proper management of the data. The authors thank adolescents living with HIV, their caregivers, and health professionals for their enthusiasm to participate in this study. The authors also thank the management and staff at Light House and Nathenje health centre for allowing us to recruit at these facilities and for providing private space for data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307

- Baker, V., Nkhoma, K., Trevelion, R., Roach, A., Winston, A., Sabin, C., Bristowe, K., & Harding, R. (2021). I have failed to separate my HIV from this pain": The challenge of managing chronic pain among people with HIV. AIDS Care, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1869148

- Bodenheimer, T., Lorig, K., Holman, H., & Grumbach, K. (2002). Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA, 288(19), 2469–2475. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.19.2469

- Brechtl, J. R., Breitbart, W., Galietta, M., Krivo, S., & Rosenfeld, B. (2001). The use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in patients With advanced HIV infection: Impact on medical, palliative care, and quality of life outcomes. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 21(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(00)00245-1

- Chou, R., Fanciullo, G. J., Fine, P. G., Adler, J. A., Ballantyne, J. C., Davies, P., Donovan, M. I., Fishbain, D. A., Foley, K. M., Fudin, J., Gilson, A. M., Kelter, A., Mauskop, A., O'connor, P. G., Passik, S. D., Pasternak, G. W., Portenoy, R. K., Rich, B. A., Roberts, R. G., … Miaskowski, C. (2009). Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. The Journal of Pain, 10(2), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.008

- Coakley, R., Wihak, T., Kossowsky, J., Iversen, C., & Donado, C. (2018). The comfort ability pain management workshop: A preliminary, nonrandomized investigation of a brief, cognitive, biobehavioral, and parent training intervention for pediatric chronic pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 43(3), 252–265. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsx112

- Department of Health. (2013). Self Care- A Real Choice, Self Care Support – A Practical Option. In: NHS (ed.).

- Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

- Evans, D., Menezes, C., Mahomed, K., Macdonald, P., Untiedt, S., Levin, L., Jaffray, I., Bhana, N., Firnhaber, C., & Maskew, M. (2013). Treatment outcomes of HIV-infected adolescents attending public-sector HIV clinics across Gauteng and Mpumalanga, South Africa. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 29(6), 892–900. https://doi.org/10.1089/aid.2012.0215

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013a). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013b). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Ghaemi, S. N. (2009). The rise and fall of the biopsychosocial model. British Journal of Psychiatry, 195(1), 3–4. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.063859

- Harding, R. (2013). Informal caregivers in home palliative care. Progress in Palliative Care, 21(4), 229–231. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743291X13Y.0000000056

- Harding, R., Clucas, C., Lampe, F. C., Leake Date, H., Fisher, M., Johnson, M., Edwards, S., Anderson, J., & Sherr, L. (2012a). What factors are associated with patient self-reported health status among HIV outpatients? A multi-centre UK study of biomedical and psychosocial factors. AIDS Care, 24(8), 963–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2012.668175

- Harding, R., Clucas, C., Lampe, F. C., Norwood, S., Leake Date, H., Fisher, M., Johnson, M., Edwards, S., Anderson, J., & Sherr, L. (2012b). Behavioral surveillance study: Sexual risk taking behaviour in UK HIV outpatient attendees. AIDS and Behavior, 16(6), 1708–1715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0023-y

- Harding, R., Lampe, F. C., Norwood, S., Date, H. L., Clucas, C., fisher, M., Johnson, M., Edwards, S., Anderson, J., & Sherr, L. (2010). Symptoms are highly prevalent among HIV outpatients and associated with poor adherence and unprotected sexual intercourse. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 86(7), 520–524. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2009.038505

- Holzemer, W., Hudson, A., Kirksey, K., Hamilton, M., & Bakken, S. (2001). The revised sign and symptom check-list for HIV (SSC-HIVrev). Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 12(5), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60263-X

- Hughes, J., Jelsma, J., Maclean, E., Darder, M., & Tinise, X. (2004a). The health-related quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS. Disability and Rehabilitation, 26(6), 371–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280410001662932

- Hughes, J., Jelsma, J., Maclean, E., Darder, M., & Tinise, X. (2004b). The health-related quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS. Disability and Rehabilitation, 26(6), 371–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280410001662932

- International Alliance of Patients Organisations. (2007). What is patient-centred healthcare? A review of definitions and principles. Available from: http://iapo.org.uk/sites/default/files/files/IAPO%20Patient-Centred%20Healthcare%20Review%202nd%20edition.pdf. Accessed 15/09/2020

- International Association For The Study Of Pain. (1986). Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, subcommittee on taxonomy. Pain. Supplement, 3, S1–226.

- Kourrouski, M. F. C., & Lima, R. A. G. D. (2009). Treatment adherence: The experience of adolescents with HIV/AIDS. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 17(6), 947–952. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692009000600004

- Lampe, F. C., Harding, R., Smith, C. J., Phillips, A. N., Johnson, M., & Sherr, L. (2010). Physical and psychological symptoms and risk of virologic rebound among patients with virologic suppression on antiretroviral therapy. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 54(5), 500–505. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ce6afe

- Lavy, V. (2007). Presenting symptoms and signs in children referred for palliative care in Malawi. Palliative Medicine, 21(4), 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216307077689

- Lorig, K. R., Ritter, P. L., Laurent, D. D., & Plant, K. (2006). Internet-based chronic disease self-management: A randomized trial. Medical Care, 44(11), 964–971. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000233678.80203.c1

- Madiba, S., & Josiah, U. (2019). Perceived stigma and fear of unintended disclosure are barriers in medication adherence in adolescents with perinatal HIV in Botswana: A qualitative study. BioMed Research International, 2019, 9623159. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9623159

- Malawi Population-Based Hiv Impact Assessment. (2016). Malawi population-based HIV impact assessment. http://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/MALAWI-Factsheet.FIN_.pdf#:~:text=The%20Malawi%20Population-Based%20HIV%20Impact%20Assessment%20%28MPHIA%29%2C%20a,information%20about%20uptake%20of%20care%20and%20treatment%20services. In: HIV/AIDS (ed.). Lilongwe: MOH

- Marcus, K. S., Kerns, R. D., Rosenfeld, B., & Breitbart, W. (2000). HIV/AIDS-related pain as a chronic pain condition: Implications of a biopsychosocial model for comprehensive assessment and effective management. Pain Medicine, 1(3), 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4637.2000.00033.x

- Mcgowan, P. T. (2012). Self-management education and support in chronic disease management. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, 39(2), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2012.03.005

- Merlin, J. S., Childers, J., & Arnold, R. M. (2013). Chronic pain in the outpatient palliative care clinic. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 30(2), 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909112443587

- Merlin, J. S., Zinski, A., Norton, W. E., Ritchie, C. S., Saag, M. S., Mugavero, M. J., Treisman, G., & Hooten, W. M. (2014). A conceptual framework for understanding chronic pain in patients with HIV. Pain Practice, 14(3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.12052

- Mitchell, C. G., & Linsk, N. L. (2004). A multidimensional conceptual framework for understanding HIV/AIDS as a chronic long-term illness. Social Work, 49(3), 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/49.3.469

- Mutwa, P. R., Van Nuil, J. I., Asiimwe-Kateera, B., Kestelyn, E., Vyankandondera, J., Pool, R., Ruhirimbura, J., Kanakuze, C., Reiss, P., Geelen, S., Van de wijgert, J., & Boer, K. R. (2013). Living situation affects adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adolescents in Rwanda: A qualitative study. PLoS One, 8(4), e60073. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060073

- Nkhoma, K., Norton, C., Sabin, C., Winston, A., Merlin, J., & Harding, R. (2018). Self-management interventions for pain and physical symptoms among people living with HIV: A systematic review of the evidence. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 79(2), 206–225. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001785

- Nkhoma, K., Seymour, J., & Arthur, A. (2013). An educational intervention to reduce pain and improve pain management for Malawian people living with HIV/AIDS and their family carers: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 14(1), 216. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-216

- Nkhoma, K., Seymour, J., & Arthur, A. (2015). An educational intervention to reduce pain and improve pain management for Malawian people living with HIV/AIDS and their family carers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 50(1), 80–90. e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.01.011

- Parker, R., Stein, D. J., & Jelsma, J. (2014). Pain in people living with HIV/AIDS: A systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17(1), 18719. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.17.1.18719

- Peltzer, K., & Phaswana-Mafuya, N. (2008). The symptom experience of people living with HIV and AIDS in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-271

- Robbins, N. M., Chaiklang, K., & Supparatpinyo, K. (2013). Undertreatment of pain in human immunodeficiency virus positive adults in Thailand. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 45(6), 1061–1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.06.010

- Rosenfeld, B., Breitbart, W., Mcdonald, M. V., Passik, S. D., Thaler, H., & Portenoy, R. K. (1996). Pain in ambulatory AIDS patients. II. Impact of pain on psychological functioning and quality of life. Pain, 68(2), 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03220-4

- Schmitt, J. K., & Stuckey, C. P. (2004). AIDS–no longer a death sentence, still a challenge. Southern Medical Journal, 97(4), 329–331. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.SMJ.0000118132.01508.F0

- Serchuck, L. K., Williams, P. L., Nachman, S., Gadow, K. D., Chernoff, M., & Schwartz, L. (2010). Prevalence of pain and association with psychiatric symptom severity in perinatally HIV-infected children as compared to controls living in HIV-affected households. AIDS Care, 22(5), 640–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120903280919

- Sherr, L., Lampe, F., Norwood, S., Leake Date, H., Harding, R., Johnson, M., Edwards, S., Fisher, M., Arthur, G., Zetler, S., & Anderson, J. (2008). Adherence to antiretroviral treatment in patients with HIV in the UK: A study of complexity. AIDS Care, 20(4), 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120701867032

- Simms, V., Higginson, I. J., & Harding, R. (2011). What palliative care-related problems do patients experience at HIV diagnosis? A systematic review of the evidence. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 42(5), 734–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.02.014

- Swendeman, D., Ingram, B. L., & Rotheram-borus, M. J. (2009). Common elements in self-management of HIV and other chronic illnesses: An integrative framework. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 21(10), 1321–1334. doi:10.1080/09540120902803158

- UNAIDS. (2020). UNAIDS ‘AIDSinfo’ (accessed April 2021) [Online]. [Accessed].

- Unicef Data Dashboard. (2020). Key HIV epidemiology indicators for children and adolescents and young people. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/topic/hivaids/adolescents-young-people/July 2020 ed.: UNICEF

- Vogl, D., Rosenfeld, B., Breitbart, W., Thaler, H., Passik, S., Mcdonald, M., & Portenoy, R. K. (1999). Symptom prevalence, characteristics, and distress in AIDS outpatients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 18(4), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00066-4

- Vranda, M. N., & Mothi, S. N. (2013). Psychosocial issues of children infected with HIV/AIDS. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine,, 35(1), 19–22. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.112195

- WHO. (2014). Health for the World’s adolescents: A second chance in the second de. WHO.

- World Health Organisation. (2014). Health for the World’s adolescent’s: A second chance in the second decade [online]. WHO. [Accessed 12/07/2018 2020].

- Young, S., Wheeler, A. C., Mccoy, S. I., & Weiser, S. D. (2014). A review of the role of food insecurity in adherence to care and treatment among adult and pediatric populations living with HIV and AIDS. AIDS and Behavior, 18(Suppl 5), S505–S515. doi:10.1007/s10461-013-0547-4

- Zinyemba, T. P., Pavlova, M., & Groot, W. (2020). Effects of HIV/AIDS on children's educational attainment: a systematic literature review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 34(1), 35–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12345