ABSTRACT

HIV status disclosure rates to sexual partners are low in Tanzania, despite the benefits it confers to both partners. This qualitative study drew on the Disclosure Decision Model to explore the decision by people living with HIV (PLHIV) to disclose, or not, their HIV status to their partner. Six focus group discussions and thirty in-depth interviews were conducted in Mwanza, Tanzania in 2019 with PLHIV. Topics covered decision-making around disclosure and disclosure experiences. Thematic content analysis was conducted. Most respondents reported having disclosed their status to their partners. Disclosure was reported to facilitate or hinder the attainment of social goals including having intimate relationships, raising a family, relief from distress and accessing social support. Decisions made by PLHIV about whether to disclose their status were made after weighing up the perceived benefits and risks. The sense of liberty from a guilty conscious, and not “living a lie” were perceived as benefits of disclosure, while fears of stigma, family break-up or abandonment were perceived as risks. Many participants found disclosure was beneficial in promoting their adherence to treatment and clinic appointments. Interventions to support PLHIV with disclosure should include enhanced counselling, strengthening HIV support groups and enhanced assisted partner notification services.

Background

The East and Southern African region bears the highest burden of HIV globally, accounting for 54% of people living with HIV (PLHIV) (UNAIDS, Citation2019). Despite antiretroviral therapy (ART) scale-up, including “Test and Treat” since 2016, epidemic control has not been reached, with 800,000 new infections in 2018 alone, 9% of which were in the United Republic of Tanzania (UNAIDS, Citation2019). With 75% of new infections occurring in heterosexual partnerships, interventions that prevent HIV transmission within couples need strengthening (UNAIDS, Citation2019).

Disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners, a goal emphasized by the World Health Organization (WHO), is key for HIV prevention (World Health Organization, Citation2004). Disclosure can benefit sexual partners by promoting discussion of HIV risks and a desire to access HIV testing and prevention services, including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) (Evangeli & Wroe, Citation2017; Yonah et al., Citation2014). Disclosure within couples also provides an opportunity to discuss and implement risk-reduction strategies and undertake family planning (Conserve et al., Citation2016; Hallberg et al., Citation2019).

Disclosure may also motivate PLHIV to seek treatment, thus reducing HIV-related morbidity risks, with studies showing that disclosure is associated with timely linkage to care and adherence to treatment (Lemin et al., Citation2018; Sanga et al., Citation2017). Conversely, an inability to disclose can result in a lack of moral, financial and physical support, leading to poorer outcomes and increased HIV transmission risks (Evangeli & Wroe, Citation2017; Kadowa & Nuwaha, Citation2009; Lugalla et al., Citation2012).

WHO recommends assisted partner notification to be offered to PLHIV following their diagnosis. This process involves a trained health worker supporting PLHIV to inform their partner about their HIV status and encourage them to undergo HIV testing, or, with the consent of the client, to communicate their HIV status and propose testing (Plotkin et al., Citation2018; World Health Organization, Citation2016). In line with this guidance, the 2019 Tanzanian national guidelines on HIV testing encourage couple testing and mutual disclosure of results, whilst emphasising that counsellors respect the confidentiality and privacy of the patient and act to protect patient safety (NACP, Citation2019). However, despite the favourable policy environment, the practice is still not widespread among diagnosed PLHIV in Tanzania, with disclosure rates to sexual partners between 28% and 66% within 12 months of diagnosis (Damian et al., Citation2019; Hallberg et al., Citation2019; Idindili et al., Citation2015; Knettel et al., Citation2019).

Studies from African settings investigating determinants of HIV status disclosure have shown that close relationships with a sexual partner, needing help, and being on ART promoted disclosure, while fear of stigma or abandonment were barriers to disclosure (Ebuenyi et al., Citation2014; Obermeyer et al., Citation2011; Yonah et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, disclosure patterns and experiences are often gendered, with women more vulnerable to intimate partner violence, accusations of infidelity and divorce, due to social norms and women’s frequent economic and social dependence on male partners (Evangeli & Wroe, Citation2017; Katz et al., Citation2013; Kiula et al., 2013; Knettel et al., Citation2019).

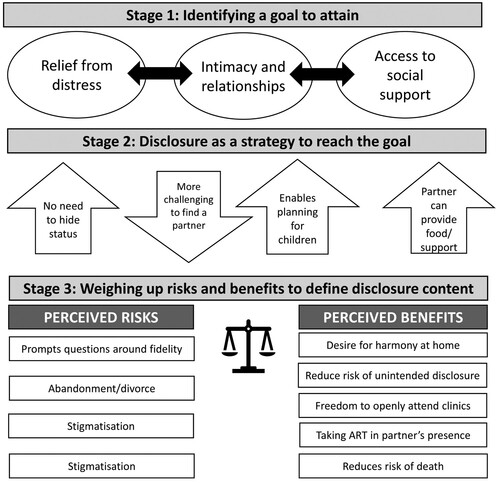

Despite these findings, few studies have explored the decision-making processes behind disclosure for PLHIV on ART, particularly in the Tanzanian context, despite the need for this evidence to inform interventions to encourage disclosure and thus promote HIV care engagement and prevention. A large body of psychological work has concerned the development of self-disclosure, including those aiming to understand drivers of decision-making in relation to social goals (Chaudoir & Fisher, Citation2010; Omarzu, Citation2000). Among these, the Disclosure Decision Model (DDM) proposes three stages that define the disclosure process. In the first stage, the disclosure decision process is activated by the possibility of accessing a social reward or “disclosure goal” such as social approval, intimacy, relief of distress, social control or identity clarification. The second stage of the DDM involves identifying to whom disclosure will occur, deciding whether disclosure is an appropriate approach to achieve the goal, and decisions around the strategies that may be adopted to achieve it. The third stage of the DDM concerns the decisions regarding the content and scope of the disclosure, which are based on weighing up the perceived risks and benefits of the disclosure event (Omarzu, Citation2000). In this analysis, we aimed to draw on the DDM to explore decision-making around disclosure to sexual partners among PLHIV on ART in North-Western, Tanzania.

Study methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in Mwanza city in North-Western Tanzania, with a population of over 700,000 inhabitants and HIV prevalence of 7.2% (NBS, Citation2017).

Recruitment and sampling

This qualitative study was nested in the Chronic Infections, Co-morbidities and Diabetes in Africa (CICADA) study, a cohort study investigating the burden of and risk factors for diabetes among adults living with and without HIV in Mwanza. It was conducted between January and October 2019 among participants living with HIV aged ≥18 years, currently married or in a sexual partnership and attending ART clinics for up to two years in Sekou-Toure and Nyamagana hospitals as identified through the patient records. Patients on ART for more than two years were excluded as people’s recollections of disclosure decisions and experiences longer ago may have faded with time. Participants were purposively sampled from the CICADA cohort, ensuring diversity in terms of age, sex, ART clinic, duration on ART and disclosure status.

Data generation

We drew on the underlying concepts of Omarzu’s Disclosure Decision Model (DDM) to inform the topic guides for data collection, including exploring the social goals that PLHIV sought to obtain through disclosure, the extent to which disclosure was used as a strategy to obtain the goal, and the perceived risks and benefits that they weighed up when deciding how and when to disclose their HIV status (Omarzu, Citation2000).

FGDs were chosen as a data generation method as they enable prevalent views among a group of people with shared characteristics, in this case, living with HIV and being in a sexual relationship to be explored.

IDIs were chosen to explore personal accounts that participants may not want to discuss in group settings, given the sensitive nature of the topic.

The lead investigator (ES), assisted by three trained research assistants, conducted the interviews. Interviews and FGD guides were piloted and instruments adjusted accordingly. Participants were provided with an information sheet before being asked for informed consent. Interviews and discussions were conducted in a private room at the clinic to ensure confidentiality and privacy and were audio-recorded. Recordings were transcribed verbatim in Swahili and before translation into English. Data were coded inductively and thematic content analysis was undertaken (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994) supported by Nvivo12.

Quality assurance

To enhance the credibility, dependability and confirmability of the study (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985; Shenton, Citation2004), we triangulated information gathered through the IDI and FGD. Furthermore, discussions were recapped with participants to ensure they agreed with the content. Dependability was addressed by training and supervision of the research assistants and ensuring transcripts were professionally translated and checked by the bilingual first author. The study followed the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines for reporting qualitative research (Tong et al., Citation2007).

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was received from the Lake Zone Institutional Review Board at the National Institute for Medical Research in Mwanza, Tanzania.

Results

Six FGDs were held, each with 8–12 participants, as well as thirty IDIs ( and ). Four participants participated in both an IDI and FGD. Most participants reported disclosing to their sexual partners, while seven reported planning to disclose in the future, and four had not decided whether to disclose. Most respondents had completed primary education, were self-employed and some were small-scale farmers.

Table 1. Age and sex of participants in FGDs.

Table 2. Characteristics of IDI participants.

Our findings illustrate the three stages of the DDM in relation to how PLHIV on ART decided whether or not to disclose their HIV status, identifying (i) social rewards and goals sought through the disclosure process; (ii) disclosure as a strategy to achieve these goals, and (iii) perceived risks and benefits that influenced the content and scope of the disclosure ().

Figure 1. The Disclosure Decision Model in the context of HIV status disclosure to intimate partners. Adapted from (Omarzu, Citation2000).

Stage one: social rewards and goals influenced by disclosure decisions

The most commonly articulated goal that PLHIV sought through disclosure to their partners was relief from the distress of “living a lie”. Several participants reported that sharing their HIV results with their sexual partner was a liberating experience:

The advantage of sharing with your spouse, first the marriage is being at peace, you live with freedom … you will not have any fear in your heart. [FGD-Male]

… To be honest … I have no peace … my partner doesn’t know … I think maybe he will hate me if he finds out [IDI-Female 40 years]

… I have not yet shared my status with her … it is very difficult to share with someone just straight away, maybe until you stay together for a longer period and get used to each other … You might share … she panics … it will be spread among community members [IDI-Male 27]

… if she discloses her status by her age, she'll not get married … she won’t be able to get a partner … since she is still young [IDI-Female 50 years]

Stage two: Disclosure as a strategy to achieve social goals

The act of disclosing their HIV status was evoked by some women as a strategy for facilitating planning for the future, including discussions around safe childbearing desires or contraceptive needs:

..It helps to arrange safe reproduction methods … whether we should continue giving birth or end … . [FGD-Female]

It is a dangerous situation … if your children are still young or you don’t have children yet, you realize that the generation will perish or the next generation will be worthless … it is somehow better for us we had stopped bearing children [IDI-Female 50 years]

… some time you may be lacking money to buy needs like fruits. Perhaps your spouse may have money to give you since he knows the importance … so if he doesn’t know it is a disadvantage [IDI –Female 40 years]

… You will take your medicines freely without hiding … also when you are required to go to the clinic and you are sick, he can go and collect your medicines … .[FGD-female]

I had to lie to him that I was going to see my relative … so I can go to the clinic to pick my medicines … sometimes … I had to postpone … . [IDI- Female 40 years]

Some participants requested additional assistance from HIV counsellors to implement the strategy of informing their partner in cases where disclosure was a challenge, while others felt that it would be facilitated by more community-level efforts and stigma-reduction interventions to encourage HIV testing and disclosure:

… You may have a difficult man, you can even give his number to a doctor so that he can advise him so that he can check his status. [FGD-Female]

Stage three: Perceived benefits and risks of disclosure shaping disclosure decisions

The reported anticipated and experienced benefits of disclosing included the desire for harmony at home, freedom to attend HIV clinic visits and being able to take medication in their partner’s presence, as one man explained:

… If I hide (my HIV status) … I will not have the freedom of using medicine in her presence … someone can even dare to go toilet to drink medicine (laughter). [FGD – both genders]

I just thought … when I come home with my medicines “where I am going to hide them”? She could see them (ARTs) by accident it will be a bigger problem and thus I had to share with her. [IDI- Male 41 years]

… I just feared she might panic … you know that is difficult … the problem is breakage of the family … I'm thinking of how will I live with (take care of) children if she decides to leave? [IDI-Male 48 years]

… You find a man having many side chicks, so it is difficult to share with your spouse while you are aware that you are not faithful … [IDI- Male 57 years]

If she becomes sick and dies … this is bad for me and my family because if I had told her she could have used medicine and got well [IDI-Male 40 years]

Discussion

This study drew on Omarzu’s Disclosure Decision Model to explore the social rewards and goals sought by PLHIV on ART through the status disclosure process to their partners, the way in which disclosure (or not) could be used as a strategy to achieve these goals and the perceived risks and benefits that influenced the content and scope of the disclosure.

In our study, goals which underlay disclosure decisions were intimacy, relief of distress and access to social support. Most participants reported having disclosed, citing the sense of liberty, freedom from a guilty conscious and not having to “live a lie” as key perceived benefits that drove their decision. Having disclosed to their partners, many participants also reported practical advantages. Firstly, and in alignment with other studies in this area, we found that participants found it easier to adhere to clinic visits and treatment-taking once disclosure had occurred (Gultie et al., Citation2017; Maeri et al., Citation2016). Moral and financial support were mentioned as benefits of disclosure in line with findings other African settings (Gultie et al., Citation2017; Maeri et al., Citation2016; Yaya et al., Citation2015).

These findings emphasize the value of interventions that support PLHIV on ART to disclose to their partners as a means to improve adherence and thereby increase viral suppression rates, an outcome which is of critical importance to ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 (UNAIDS, Citation2014). Such interventions include ongoing and enhanced counselling. Whilst disclosure counselling often happens immediately following an HIV diagnosis, our findings suggest that it also needs to be provided to people who have initiated ART and not yet disclosed their status. Furthermore, given the complexity of the disclosure process, it is important that care providers working with PLHIV have appropriate skills to assess the potential outcomes in relation to each client’s circumstances and provide tailored counselling and strategies for when and how to disclose (Damian et al., Citation2019). Finally, counselling sessions may need to be repeated for some patients, as they work through the decision-making process, with a focus on the likely benefits. Sharing positive experiences of disclosure through attendance at support groups for PLHIV is also likely to encourage and motivate those who are hesitant to share their status with their partners.

In addition, our findings point to the importance of implementing WHO recommendations on strengthening assisted partner notification (WHO, Citation2016). Most of the cited risks of disclosure related to fears of being rejected or abandoned, with many participants explicitly calling for greater support in discussing their HIV status with their partner. Counsellors should impart communication and negotiation skills for disclosure to help PLHIV share their HIV status, as well as assist with partner notification, but only when consent is given by the client. Assisted partner notification can reduce stress associated with disclosure as well as leading to high positivity rates among tested partners of PLHIV (Arrey et al., Citation2015; Kababu et al., Citation2018).

There are limitations to this study. Firstly, social desirability may have influenced participants’ responses, particularly with regards to whether they had disclosed to a partner. However, using IDI as well as FGD for data collection, and using well-trained interviewers reduced this risk. Secondly, we recruited individuals on ART for up to two years, and disclosure experiences may differ before ART initiation and for PLHIV on treatment for longer durations. Finally, our participants were recruited from a cohort study and may not represent the broader population in this setting.

In conclusion, we found that relief from the stress of secrecy, greater intimacy and social support as the main social goals that they sought through disclosure. The reported benefits of disclosure were multiple and included reducing stress, accessing financial and moral support, improved adherence to treatment and a better ability to make plans for their future. PLHIV weighed up the risks and benefits of disclosure before deciding whether to share their HIV status with their spouse or partner. To enable more PLHIV to achieve the benefits of achieving their disclosure goals and to identify more undiagnosed partners, interventions should focus on improved disclosure counselling, strengthening HIV support groups, assisted partner notification services and improving community education to reduce the stigmatisation that often undermines HIV status disclosure.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very thankful to all study participants and staff from CICADA project and the management of NIMR-Mwanza Research Centre for their support. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of AAS, NEPAD Agency, Wellcome Trust, the UK government or Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. None of the funders had any role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish results or preparation of the manuscript. We also thank the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology (COSTECH) for providing training on writing scientific papers in 2020.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available after the data sharing request is approved by the Medical Research Coordinating Committee at NIMR.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arrey, A. E., Bilsen, J., Lacor, P., & Deschepper, R. (2015). “It’s My secret” : Fear of disclosure among Sub-saharan African migrant women living with HIV / AIDS in Belgium. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0119653. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119653

- Chaudoir, S., & Fisher, J. D. (2010). The disclosure processes model. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 236–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018193

- Conserve, D. F., Hill, C., Groves, A. K., Maman, S., & Hill, C. (2016). Effectiveness of interventions promoting HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 19(10), 1763–1772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1006-1

- Damian, D. J., Ngahatilwa, D., Fadhili, H., Mkiza, J. G., Mahande, M. J., Ngocho, J. S., & Msuya, S. E. (2019). Factors associated with HIV status disclosure to partners and its outcomes among HIV-positive women attending care and treatment clinics at Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. PLoS ONE, 14(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211921

- Ebuenyi, I. D., Ogoina, D., Ikuabe, P. O., Harry, T. C., Inatimi, O., & Chukwueke, O. U. (2014). Prevalence pattern and determinants of disclosure of HIV status in an anti retroviral therapy clinic in the Niger delta region of Nigeria. African Journal of Infectious Diseases, 8(2), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajid.v8i2.2

- Evangeli, M., & Wroe, A. L. (2017). HIV disclosure anxiety: A systematic review and theoretical synthesis. AIDS and Behavior, 21(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1453-3

- Gultie, T., Genet, M., & Sebsibie, G. (2017). Disclosure of HIV-positive status to sexual partner and associated factors among ART users in Mekelle hospital. HIV/AIDS – Research and Palliative Care, 7, 209–214. https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S84341

- Hallberg, D., Kimario, T. D., Mtuya, C., Msuya, M., & Björling, G. (2019). Factors affecting HIV disclosure among partners in Morongo, Tanzania. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 10(January), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2019.01.006

- Idindili, B., Selemani, M., Bakar, F., Thawer, S. G., Gumi, A., Mrisho, M., Kahwa, A. M., & Massaga, J. J. (2015). Enhancing HIV status disclosure and partners’ testing through counselling in Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Health Research, 17(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4314/thrb.v17i3.4

- Kababu, M., Sakwa, E., Karuga, R., Ikahu, A., Njeri, I., Kyongo, J., Khamali, C., & Mukoma, W. (2018). Use of a counsellor supported disclosure model to improve the uptake of couple HIV testing and counselling in Kenya: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5495-5

- Kadowa, I., & Nuwaha, F. (2009). Factors influencing disclosure of HIV status in Mityana district of Uganda. African Health Sciences, 9(1), 26–33.

- Katz, I. T., Ryu, A. E., Onuegbu, A. G., Psaros, C., Weiser, S. D., Bangsberg, D. R., & Tsai, A. C. (2013). Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: Systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16(3 Suppl 2), https://doi.org/10.7448/ias.16.3.18640

- Knettel, B. A., Minja, L., Chumba, L. N., Oshosen, M., Cichowitz, C., Mmbaga, B. T., & Watt, M. H. (2019). Serostatus disclosure among a cohort of HIV-infected pregnant women enrolled in HIV care in Moshi, Tanzania: A mixed-methods study. SSM – Population Health, 7(October 2018), 100323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.11.007

- Lemin, A. S., Rahman, M. M., & Pangarah, C. A. (2018). Factors affecting intention to disclose HIV status among adult population in Sarawak, Malaysia. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2194791

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry (1st ed). Sage Publications. https://books.google.co.za/books?hl=en&lr=&id=2oA9aWlNeooC&oi=fnd&pg=PA5&sig=GoKaBo0eIoPy4qeqRyuozZo1CqM&dq=naturalistic+inquiry&prev=http://scholar.google.com/scholar%3Fq%3Dnaturalistic%2Binquiry%26num%3D100%26hl%3Den%26lr%3D&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=natu

- Lugalla, J., Yoder, S., Sigalla, H., & Madihi, C. (2012). Social context of disclosing HIV test results in Tanzania. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 14(SUPPL. 1), S53–S66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2011.615413

- Maeri, I., Ayadi, A. E., Getahun, M., Charlebois, E., Tumwebaze, D., Itiakorit, H., Owino, L., Kwarisiima, D., Ssemmondo, E., Sang, N., Kabami, J., Clark, T. D., Petersen, M., Cohen, C. R., Bukusi, E. A., Havlir, D., Camlin, C. S., Collaboration, S., Maeri, I., … Camlin, C. S. (2016). How can I tell ?” Consequences of HIV status disclosure among couples in eastern African communities in the context of an ongoing HIV “test-and-treat” trial. AIDS Care, 28(Suppl 3), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1168917

- Miles, M., & Huberman, M. (1994). An expanded source book: Qualitative data analysis. Sage Publications.

- NACP. (2019). National comprehesive guidelines on HIV testing services. Guideline, 53(Issue 9), 1689–1699. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- NBS. (2017). Tanzania HIV Impact survey (THIS) 2016-2017. Report, 1(December 2017), 6. https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Tanzania_SummarySheet_A4.English.v19.pdf

- Obermeyer, C. M., Baijal, P., & Pegurri, E. (2011). Facilitating HIV disclosure across diverse settings: A review. American Journal of Public Health, 101(6), 1011–1023. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300102

- Omarzu, J. (2000). A disclosure decision model: Determining how and when individuals will self-disclose. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(2), 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_05

- Plotkin, M., Kahabuka, C., Christensen, A., Ochola, D., Betron, M., Njozi, M., Maokola, W., Kisendy, R., Mlanga, E., Curran, K., Drake, M., Kessy, E., & Wong, V. (2018). Outcomes and experiences of men and women with partner notification for HIV testing in Tanzania: Results from a mixed method study. AIDS and Behavior, 22(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1936-x

- Sanga, E. S., Lerebo, W., Mushi, A. K., Clowes, P., Olomi, W., Maboko, L., & Zarowsky, C. (2017). Linkage into care among newly diagnosed HIV-positive individuals tested through outreach and facility-based HIV testing models in Mbeya, Tanzania: A prospective mixed-method cohort study. BMJ Open, 7(4), e013733. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013733

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/452e/3393e3ecc34f913e8c49d8faf19b9f89b75d.pdf https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-2004-22201

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criterio for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32- item checklist for interviews and focus group. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- UNAIDS. (2014). FAST-TRACK ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2686_WAD2014report_en.pdf

- United Nations Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2019). UNAIDS data 2019. 476. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019-UNAIDS-data_en.pdf_aidsinfo.unaids.org

- WHO. (2016). HIV testing services HIV self-testing and partner notification. Suppliment, December.

- World Health Organization. (2004, December). Guidelines on HIV self-testing and partner notification. Supllement to Consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services.104. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/251655/

- Yaya, I., Saka, B., Landoh, D. E., Patchali, P. M., Patassi, AAÈ, Aboubakari, A. S., Makawa, M. S., N’Dri, M. K., Senanou, S., Lamboni, B., Idrissou, D., Salaka, K. T., & Pitché, P. (2015). HIV status disclosure to sexual partners, among people living with HIV and AIDS on antiretroviral therapy at Sokodé regional hospital, Togo. PLoS ONE, 10(2), e0118157–9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118157

- Yonah, G., Fredrick, F., & Leyna, G. (2014). HIV serostatus disclosure among people living with HIV/AIDS in mwanza, Tanzania. AIDS Research and Therapy, 11(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-6405-11-5