ABSTRACT

Understanding the characteristics of people living with HIV who interrupt antiretroviral therapy (ART) is critical for designing client-centered services to ensure optimal outcomes. We assessed predictors of treatment interruption in 22 HIV clinics in Nigeria. We reviewed records of HIV-positive patients aged ≥15 years who started ART 1 January and 31 March 2019. We determined treatment status over 12 months as either active, or interrupted treatment (defined as interruption in treatment up to 28 days or longer). Potential predictors were assessed using Cox hazard regression models. Overall, 1185 patients were enrolled on ART, 829 (70%) were female, and median age was 32 years. Retention at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months was 85%, 80%, 76%, 72%, and 68%, respectively. Predictors of treatment interruption were post-secondary education (p = 0.04), diagnosis through voluntary counseling and testing (p < 0.001), receiving care at low-volume facilities (p < 0.001), lack of access to a peer counselor (p < 0.001), and residing outside the clinic catchment area (p = 0.03). Treatment interruption was common but can be improved by focusing on lower volume health facilities, providing peer support especially to those with higher education, and client-centered HIV services for those who live further from clinics..

Introduction

Increased access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) has resulted in declining mortality and improved quality of life for people living with HIV (PLHIV) (Folasire et al., Citation2012; Oguntibeju, Citation2012). However, the individual and public health benefits of ART can only be achieved if patients are retained in an HIV treatment program, adherent to ART, and achieve viral suppression (Stricker et al., Citation2014). These goals are threatened by treatment interruption.

Loss to follow-up (LTFU) or treatment interruption is influenced by many factors including sex (Asiimwe et al., Citation2015; Balogun et al., Citation2019; Oguntibeju, Citation2012; Onoka et al., Citation2012; Tadesse & Haile, Citation2014; Webb & Hartland, Citation2018), age (Asiimwe et al., Citation2015; Assemie et al., Citation2018; Berheto et al., Citation2014; Hønge et al., Citation2013; Meloni et al., Citation2014), educational status (Akilimali et al., Citation2017; Hønge et al., Citation2013), marital status (Alvarez-Uria et al., Citation2013; Bekolo et al., Citation2013; Meloni et al., Citation2014), occupation (Mberi et al., Citation2015; Tiruneh et al., Citation2016), disclosure status (Akilimali et al., Citation2017; Seifu et al., Citation2018), distance from health facilities (Bekolo et al., Citation2013), and support from caregivers (Agaba et al., Citation2017; Eshun-Wilson et al., Citation2019). In addition, clinical- and treatment-related factors such as baseline World Health Organization (WHO) stage (Meloni et al., Citation2014; Odafe et al., Citation2012), baseline CD4 count (Bekolo et al., Citation2013; Odafe et al., Citation2012; Tiruneh et al., Citation2016), prevalent opportunistic infections (OIs) (Asiimwe et al., Citation2015), baseline functional status (Ayele et al., Citation2015; Brinkhof et al., Citation2009; Eshun-Wilson et al., Citation2019; Mekonnen et al., Citation2019; Odafe et al., Citation2012), OI prophylaxis (Assemie et al., Citation2018; Bekolo et al., Citation2013; Berheto et al., Citation2014), and ART regimen type (Tadesse & Haile, Citation2014; Tiruneh et al., Citation2016) play a role.

Akwa Ibom, one of 36 states in Nigeria, and home to over 10% (188,562) of the estimated 1,832,266 PLHIV in the country (National Agency for the Control of AIDS [NACA], Citation2019) had initiated only. 120,000 (63.6%) individuals on ART by March 2020 (Nigeria country operational plan [COP], Citation2020). Yet even for those linked to ART, treatment interruption remains a persistent problem nationally and in Akwa Ibom (Data.FI, Palladium., Citation2020). The U. S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) therefore prioritized Akwa Ibom for an intensified HIV treatment surge activities from 2019 with a goal of achieving epidemic control by September 2020 (Nigeria country operational plan [COP], Citation2020). Surge activities have included index and targeted community testing, community initiation and maintenance of ART.

In the context of Akwa Ibom’s substantial HIV burden, challenges in delivery of HIV services, and less-than-ideal service access for PLHIV makes retaining patients more challenging, understanding the predictors of treatment interruption is critical. Identifying these predictors will help reduce AIDS-related deaths and new HIV infections and, ultimately, achieve epidemic control. Our study aimed to determine predictors of treatment interruption among patients enrolled at the beginning of the PEPFAR surge activities.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted in Akwa Ibom State, southern Nigeria. The state comprises 31 local government areas (LGAs), six of which border the Atlantic Ocean. Agriculture is the predominant economic activity for upland dwellers, whereas the riverine and coastal communities engage predominantly in fishing. In urban areas, petty trading, artisanship, and white-collar services are practiced. Many riverine and coastal communities are separated by marshes, ravines, creeks, and swamps making the terrain difficult and transportation costs prohibitive to access facility care.

HIV treatment services are implemented by Strengthening Integrated Delivery of HIV/AIDS Services (SIDHAS), a United States Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded project led by FHI 360, that supports the government of Nigeria to implement HIV services. In Akwa Ibom, SIDHAS supports 102 health facilities across 21 of the 31 LGAs. The 2016 Nigerian National Guidelines for HIV and AIDS Treatment, revised in 2018 (FMOH, Citation2016) recommended ART for all HIV-positive individuals, irrespective of CD4. Tenofovir, lamivudine, and efavirenz was initiated as 1st line. In 2018 eligible adults, adolescents, and older children were transitioned to tenofovir/lamivudine and dolutegravir with zidovudine as an alternative to tenofovir: and efavirenz as an alternative for dolutegravir for tuberculosis/HIV-coinfected patients.

Clinical evaluation and treatment

After diagnosis, clinical assessment, WHO clinical staging, and basic laboratory tests are conducted, ART is initiated on the same day or within 14 days of diagnosis. After ART initiation, patients are seen monthly for the first three–six months and once every three–six months thereafter if they are virally suppressed. At each visit, weight, WHO clinical stage, and OIs are assessed and recorded. Viral load testing is done at three, and six months after ART initiation and annually thereafter (FMOH, Citation2016). Patients are re-evaluated six months from ART initiation and if “stable” – that is viral load <1000 copies/mL, with no OIs, and good adherence to ART – they are enrolled in one of the appropriate differentiated service delivery (DSD) models i.e., community ART refill clubs (CARCs), community pharmacy ART refill points (CPARPs); and fast-track refill services, in which stable patients receive three or six months of ART refills (multi-month dispensing [MMD3 and MMD6]).

Selection criteria

All 22 health facilities supported by SIDHAS were included in the study. The total sample size was allocated proportionally among each hospital based on the number of patients on ART.

Data collection

Baseline and follow-up client data are routinely recorded on paper files and entered into the Lafiya Management Information System (LAMIS) – an electronic medical record system that houses most of Nigeria’s HIV treatment data. These primary records are routinely audited by the national AIDS program together with a built-in data quality assurance module for data accuracy. The study team abstracted de-identified LAMIS records for patients who initiated ART in the selected facilities between 1 January 2019 and 31 March 2019 and reviewed their clinic records to determine if they had interrupted treatment within the first 12 months of ART. Patients who were aged ≥15 years the time of HIV diagnosis were included. We excluded patients transferred into the facility with unknown ART initiation dates, and those who started ART outside the period of interest.

Baseline data retrieved from LAMIS included clients’ social demographics (sex, age, marital status, educational status, occupation, and residential distance from health facility), care entry point (e.g., facility outpatient, community outreach, prevention of mother-to-child transmission [PMTCT] clinic, etc.), clinical characteristics (recent OIs), and ART regimen.

Other information – such as client status at different time points, duration on ART, and residential categorization (defined as “within LGA” if address was within the designated catchment area of the health facility, otherwise “outside LGA”) – were gathered from patients’ paper records.

Data abstracted from either LAMIS or the patient charts were exported to a data collection sheet specifically designed for this study and cleaned using data management features in Microsoft Excel. Case managers – staff responsible for patient adherence within these health facilities – were trained on data collection and were responsible for abstracting client level data.

Sites were categorized as tier 1‒3 based on the number of patients receiving ART: Tier 1 ≥ 1500 clients; Tier 2, 500‒1499 clients; and Tier 3 having < 500 clients.

Ethical approval

Permission to analyze program data was obtained from the Akwa Ibom State Health Research Ethics Committee (HREC) and the FHI 360 Office of International Research Ethics. Patient informed consent was not required because only routine, anonymous, operational monitoring data were collected and analyzed.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome of interest was treatment interruption – defined as not picking up ART refill for 28 days or longer from the last expected refill appointment – within 12 months of ART initiation.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 20. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to determine the probability of retention at 1st, 3rd, 6th, 9th, and 12th months after ART initiation. Time to treatment interruption was calculated as the time between the date of ART initiation and the date of treatment interruption. Potential predictors of treatment interruption were assessed using risks regression model in SPSS. Cox hazards regression models were used to estimate crude and adjusted hazard ratios (AHRs) and 95% confidence interval for covariates of interest. We adjusted for the effects of selected baseline characteristics in our multivariable regression models. The variables included in the regression model were those previously reported to be associated with either attrition, treatment interruption, or mortality in other studies (Brinkhof et al., Citation2009/ 2008; Dalhatu et al., Citation2016; Akilimali et al., Citation2017). Explanatory variables that had more than 5% missing value were excluded from the final analysis.

Results

Sociodemographic and baseline characteristics of PLHIV

Between January and March 2019, 1185 PLHIV initiated ART across 22 sites. The median age at enrollment in HIV care was 32 years (IQR: 24‒40). Of the total, 829 (70%) were female, 603 (60%), were married; and 529 (45%) had completed postsecondary education ().

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of HIV-positive patients initiated on ART at 22 facilities, Akwa Ibom, Nigeria, January–March 2019.

With regard to entry point into HIV care, 504 (43%) were identified through outpatient departments, 153 (13%) through community outreach, and 406 (34%) through voluntary counseling and testing (VCT).

Only 440 (44%) were known to have disclosed their HIV-positive status to a partner, family member, or friend. Also, 450 (38%) had named a treatment supporter, and 988 (83%) reported being assigned a peer counselor immediately after ART initiation for adherence support. The majority, 964 (81%), accessed ART services in facilities located within communities where they lived (within LGA), while 221 (19%) received ART outside their residential locations.

At baseline, 534 (45%) patients were on tenofovir, lamivudine, and dolutegravir; 641 (54%) were on tenofovir and efavirenz; and 1% were on an alternative first-line regimen. Also, at baseline, 573 (48%) had a documented OI ().

Follow-up

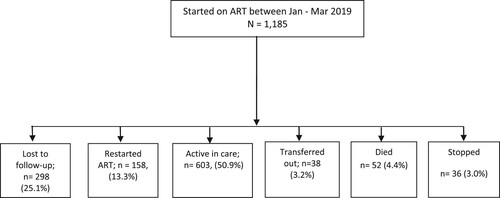

Of 1186 clients enrolled, 603 (50.9%) remained active till end of the 12th month, while 38 (3.2%) transferred to continue care at other facilities as seen in .

above also shows that client continuity in treatment differed by age (p = 0.001); marital status (p = 0.001); education (p = 0.006); HIV care and treatment entry point (p <0.001); residential distance from clinic (p = 0.016); and ART site category (p <0.001).

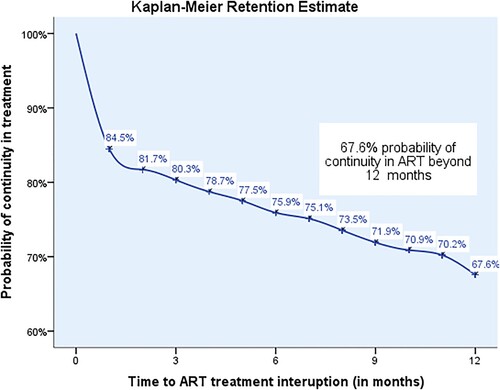

The Kaplan-Meier plot in shows the breakdown of the survival status at month 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 after ART initiation. The Kaplan-Meier probability of clients retained on ART at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after ART initiation was 85%, 80%, 76%, 72%, and 68%, respectively ().

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier 12-month retention probabilities for PLHIV initiated on ART January to March 2019.

Factors significantly associated with treatment interruption on multivariable analysis included having postsecondary education [aHR 1.7 (p-value = 0.04; 95% CI:1.02–2.71)] and enrolling through VCT [aHR 1.8 (p-value < 0.001; 95% CI: 1.41–2.35)]. In addition, PLHIV in low-client-volume sites (Tier 3) had higher risk of treatment interruption [aHR 0.57 (p-value < 0.001; 95% CI: 0.42–0.77] compared to those in Tier 2 and Tier 1. Clients who had not been assigned peer counselors [aHR 1.7 (p-value < 0.001; 95% CI: 1.35–2.09] and those residing outside LGAs [aHR 1.265 (p-value < 0.03; 95% CI: 1.03–1.56] also had higher risk of treatment interruption ().

Table 2. Analysis of factors associated with treatment interruption in HIV-positive patients on ART in Akwa Ibom January–March 2019.

Discussion

The 12-month retention rate of 68% in the PLHIV cohort in Nigeria was substantially lower than the 98% retention benchmark set by PEPFAR Nigeria (Nigeria country operational plan [COP], Citation2020) and highlights the challenges of continuity of HIV treatment in Akwa Ibom. In addition, this is lower than the 12-month retention of 81.2% previously reported from a nationally representative sample (Dalhatu et al., Citation2016), and an average of 80% across 39 cohorts in sub-Saharan Africa (Fox & Rosen, Citation2010), and calls for supportive retention interventions (Penn et al., Citation2018).

Similar to other studies that have reported highest drop-off in the first month of ART initiation (Aliyu et al., Citation2019; Alvarez-Uria et al., Citation2013; Brinkhof et al., Citation2009), our study finding shows up to 16% of treatment interruptions occurred within the first month of ART initiation; signifying that these months are critical to maintaining patients in care. Although we did not investigate reasons for treatment interruption in our study population within their first month of ART initiation, up to 48.9% of the study cohort presented with opportunistic infection after ART initiation. Poor baseline clinical and immunological status are associated with increased mortality among PLHIV (Rubaihayo et al., Citation2015). However, accounting for all deaths in low-income countries is challenging as mortality reporting is mostly passive, and deaths not reported to health facilities may be misclassified as LTFU. The mortality rate in our study was 4.4%, lower than in other Nigerian studies (Eguzo et al., Citation2014) possibly because some patients reported as having interrupted treatment may have actually died (Asiimwe et al., Citation2015; Harries et al., Citation2010).

Our study did not show any significant difference in treatment interruption rates between PLHIV started on ART with dolutegravir-based regimens compared to those on the efavirenz-based or other regimens. Other studies citing adverse events with efavirenz-based regimens have reported more discontinuations on that regimen than on dolutegravir-based ones (Nabitaka et al., Citation2020). Further analysis could be done with a larger cohort and with longer follow-up to determine if dolutegravir-based regimens have retention benefits.

Our analysis also showed no difference in risk of treatment interruption by sex unlike studies that showed higher rates among males (Brinkhof et al., Citation2009; Dalhatu et al., Citation2016; Tadesse & Haile, Citation2014).

We observed twice the treatment interruption rates among those who had completed postsecondary education when compared to those with no formal education. In contrast, other studies in similar settings where treatment interruption among those without formal education was higher (Charurat et al., Citation2010). This observation calls for strategies that address the unique care needs of those with higher education.

Treatment interruption was twice as high among patients who were diagnosed through VCT. It has been reported elsewhere that patients diagnosed through VCT have less advanced disease and may not perceive themselves as requiring medical care nor appreciate the importance of remaining in HIV care (Babatunde et al., Citation2015, Oct 14). Promoting adherence is key in retaining PLHIV especially early following initiation of ART. Some studies have highlighted successes in interventions such as Short Message Service (SMS) reminders, phone calls, and home visits (Shah et al., Citation2019; Amankwaa et al., Citation2018) in addition to implementation of treatment support systems.

Similar to other studies, our analysis indicated that assigning patients to peer counselors was associated with less treatment interruption. Peer supporters – PLHIV who have been trained to provide basic adherence counseling and psychosocial support – have been shown to improve outcomes among PLHIV (Monroe et al., Citation2017).

As expected, patients who went to health facilities outside the geographical area where they resided had higher treatment interruption rates. This is not surprising because transportation across the vast Akwa Ibom State increases the cost of accessing care. Some studies show that clinic visits are easier to keep when transport distances are shorter, reducing the time and expense required to keep appointments (Bilinski et al., Citation2017; Kolawole et al., Citation2017). However, with the introduction of differentiated service delivery to shift service settings from hospital-based clinics to communities (FMOH, Citation2016), better retention outcomes can be achieved (Faturiyele et al., Citation2018; PEPFAR Solutions, Citation2018).

Health workforce constraint at low volume sites could be a limiting factor for achieving better outcomes for PLHIV (Dalhatu et al., Citation2016). The introduction of the task-shifting and task-sharing policy in Nigeria (Federal Ministry of Health, Citation2014) was aimed at reducing gaps in services provision across these sites. However, our study reported significant variation in retention by sites’ patient volume with high- and medium-volume sites generally having better retention rates. Some studies have recommended a combination of significant training, support and other interventions where task shifting is implemented, for equivalent outcomes irrespective of site type (Emdin et al., Citation2013).

This study had some limitations. First, because we used routine program records, data were missing for some demographic, clinical, and laboratory variables, including but not limited to those assessed in the study, that might help predict treatment interruption. We recruited a cohort of individuals who started ART in the first quarter of 2019. This cohort may not be typical of patients who seek care the rest of the year. Lastly, these data are from a unique state in Nigeria and may not be generalizable to other states. Nonetheless, the analysis shows important predictors of treatment interruption – such as post-secondary education, diagnosis through VCT, seeking care outside the geographic catchment area – which, when addressed, might improve program outcomes.

Conclusion

Almost half of PLHIV in our cohort were found to have interrupted ART. We also identified important predictors of LTFU, a finding that provides programs with opportunities to improve retention. Specific interventions are required to support patients with higher educational status and those diagnosed through VCT. Continued work is needed to improve care at low-volume and potentially understaffed facilities. Ongoing efforts also are required to reduce stigma that limits disclosure and may prompt patients to seek care far from where they live.

Acknowledgements

We thank PEPFAR through USAID for providing the resources to carry out this study. We also thank all staff members of FHI 360 Akwa Ibom State Office and the health facilities in Akwa Ibom State that participated in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agaba, P. A., Meloni, S. T., Sule, H. M., Agbaji, O. O., Sagay, A. S., Okonkwo, P., Idoko, J. A., & Kanki, P. J. (2017). Treatment outcomes among older human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in Nigeria. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 4(2), ofx031. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofx031

- Akilimali, P. Z., Musumari, P. M., Kashala-Abotnes, E., Kayembe, P. K., Lepira, F. B., Mutombo, P. B., Tylleskar, T., Ali, M. M., & Faragher, E. B. (2017). Disclosure of HIV status and its impact on the loss in the follow-up of HIV-infected patients on potent anti-retroviral therapy programs in a (post-) conflict setting: A retrospective cohort study from Goma, democratic Republic of Congo. PLOS ONE, 12(2), e0171407. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171407

- Aliyu, A., Adelekan, B., Andrew, N., Ekong, E., Dapiap, S., Murtala-Ibrahim, F., Nta, I., Ndembi, N., Mensah, C., & Dakum, P. (2019). Predictors of loss to follow-up in art experienced patients in Nigeria: A 13-year review (2004–2017). AIDS Research and Therapy, 16(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-019-0241-3

- Alvarez-Uria, G., Naik, P. K., Pakam, R., & Midde, M. (2013). Factors associated with attrition, mortality, and loss to follow up after antiretroviral therapy initiation: Data from an HIV cohort study in India. Global Health Action, 6(1), 21682. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v6i0.21682

- Amankwaa, I., Boateng, D., Quansah, D. Y., Akuoko, C. P., & Evans, C. (2018). Effectiveness of short message services and voice call interventions for antiretroviral therapy adherence and other outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 13(9), e0204091. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204091. PMID: 30240417; PMCID: PMC6150661.

- Asiimwe, S. B., Kanyesigye, M., Bwana, B., Okello, S., & Muyindike, W. (2015). Predictors of dropout from care among HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy at a public sector HIV treatment clinic in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Infectious Diseases, 16(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1392-7

- Assemie, M. A., Muchie, K. F., & Ayele, T. A. (2018). Incidence and predictors of loss to follow up among HIV-infected adults at Pawi general hospital, northwest Ethiopia: Competing risk regression model. BMC Research Notes, 11(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3407-5

- Ayele, W., Mulugeta, A., Desta, A., & Rabito, F. A. (2015). Treatment outcomes and their determinants in HIV patients on anti-retroviral treatment program in selected health facilities of Kembata and Hadiya zones, southern nations, nationalities and peoples region, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 826. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2176-5

- Babatunde, O., Ojo, O. J., Atoyebi, O. A., Ekpo, D. S., Ogundana, A. O., Olaniyan, T. O., & Owoade, J. A. (2015 Oct 14). Seven-year review of retention in HIV care and treatment in federal medical centre Ido-ekiti. Pan African Medical Journal, 22(139), 139. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2015.22.139.4981

- Balogun, M., Meloni, S. T., Igwilo, U. U., Roberts, A., Okafor, I., Sekoni, A., Ogunsola, F., Kanki, P. J., & Akanmu, S. (2019). Status of HIV-infected patients classified as lost to follow up from a large antiretroviral program in southwest Nigeria. PloS One, 14(7), e0219903. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219903

- Bekolo, C. E., Webster, J., Bateganya, M., Sume, G. E., & Kollo, B. (2013). Trends in mortality and loss to follow-up in HIV care at the Nkongsamba regional hospital, Cameroon. BMC Research Notes, 6(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-6-512

- Berheto, T. M., Haile, D. B., & Mohammed, S. (2014). Predictors of loss to follow-up in patients living with HIV/AIDS after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. North American Journal of Medical Sciences, 6(9), 453–459. https://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.141636

- Bilinski, A., Birru, E., Peckarsky, M., Herce, M., Kalanga, N., et al. (2017). Distance to care, enrollment and loss to follow-up of HIV patients during decentralization of antiretroviral therapy in Neno district, Malawi: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One, 12(10), e0185699.

- Brinkhof, M. W., Pujades-Rodriguez, M., & Egger, M. (2009). Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 4(6), e5790. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005790

- Charurat, M., Oyegunle, M., Benjamin, R., Habib, A., Eze, E., Ele, P., Ibanga, I., Ajayi, S., Eng, M., Mondal, P., Gebi, U., Iwu, E., Etiebet, M-A., Abimiku, A., Dakum, P., Farley, J., Blattner, W., & Myer, L. (2010). Patient retention, and adherence to antiretrovirals in a large antiretroviral therapy program in Nigeria: A longitudinal analysis for risk factors. PLoS One, 5(5), e10584. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010584

- Dalhatu, I., Onotu, D., Odafe, S., Abiri, O., Debem, H., Agolory, S., Shiraishi, R.W., Auld, A. F., Swaminathan, M., Dokubo, K., Ngige, E., Asadu, C., Abatta, E., Ellerbrock, T. V., & Anglewicz, P. (2016). Outcomes of Nigeria’s HIV/AIDS treatment program for patients initiated on antiretroviral treatment between 2004–2012. PLoS One, 11(11), e0165528. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165528

- Data.FI. (2020). Improving patient retention on antiretroviral treatment through high frequency reporting in Akwa Ibom state. Data.FI, Palladium.

- Eguzo, K. N., Lawal, A. K., Eseigbe, C. E., & Umezurike, C. (2014, August 6). Determinants of mortality among adult HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in a rural hospital in southeastern Nigeria: A 5-year cohort study. AIDS Research and Treatment, 2014, Article ID 867827. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/867827

- Emdin, C., Chong, N. J., & Millson, P. E. (2013). Non-physician clinician provided HIV treatment results in equivalent outcomes as physician-provided care: A meta-analysis. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16, 18445.

- Eshun-Wilson, I., Rohwer, A., Hendricks, L., Oliver, S., Garner, P., & Isaakidis, P. (2019). Being HIV positive and staying on antiretroviral therapy in Africa: A qualitative systematic review and theoretical model. PLoS One, 14(1), e0210408–30. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210408

- Faturiyele, I. O., Appolinare, T., Ngorima-Mabhena, N., Fatti G., Tshabalala I., Tukei V. J., & Pisa P. T. (2018). Outcomes of community-based differentiated models of multi-month dispensing of antiretroviral medication among stable HIV-infected patients in Lesotho: A cluster randomised non-inferiority trial protocol. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1069. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5961-0

- Federal Ministry of Health. (2014). Task-shifting and task sharing policy for essential health care services in Nigeria.

- Federal Ministry of Health. (2016). National Guidelines for HIV prevention treatment and care. National AIDS and STIs Control programme. https://naca.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/NATIONAL-HIV-AND-AIDS-STRATEGIC-FRAMEWORK-1.pdf

- Folasire, O. F., Irabor, A. E., & Folasire, A. M. (2012). Quality of life of people living with HIV and AIDS attending the antiretroviral clinic, University college hospital, Nigeria. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 4(1), 294. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v4i1.294

- Fox, M. P., & Rosen, S. (2010). Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007–2009: A systematic review. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 15(Suppl 1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02508.x

- Harries, A. D., Zachariah, R., Lawn, S. D., & Rosen, S. (2010). Strategies to improve patient retention on antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 15(Suppl 1), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02506.x

- Hønge, B. L., Jespersen, S., Nordentoft, P. B., Medina, C., da Silva, D., da Silva, Z. J., Østergaard, L., Laursen, A. L., & Wejse, C. (2013). Loss to follow-up occurs at all stages in the diagnostic and follow-up period among HIV-infected patients in Guinea-Bissau: A 7-year retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open, 3(10), e003499–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003499

- Kolawole, G. A., Gilbert, H. N., Dadem, N. Y., Genberg, B. L., Agaba, P. A., et al. (2017). Patient experiences of decentralized HIV treatment and care in plateau state, North central Nigeria: A qualitative study. Aids Research and Treatment, 2017, 2838059. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2838059

- Mberi, M. N., Kuonza, L. R., Dube, N. M., Nattey, C., Manda, S., & Summers, R. (2015). Determinants of loss to follow-up in patients on antiretroviral treatment, South Africa, 2004-2012: A cohort study. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0912-2

- Mekonnen, N., Abdulkadir, M., Shumetie, E., Baraki, A. G., & Yenit, M. K. (2019). Incidence and predictors of loss to follow-up among HIV infected adults after initiation of first line anti-retroviral therapy at University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital northwest Ethiopia, 2018: Retrospective follow up study. BMC Research Notes, 12(1), 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4154-y

- Meloni, S. T., Chang, C., Chaplin, B., Rawizza, H., Jolayemi, O., Banigbe, B., Okonkwo, P., & Kanki, P. (2014). Time-Dependent predictors of loss to follow-Up in a large HIV treatment cohort in Nigeria. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 1(2), ofu055. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofu055

- Monroe, A., Nakigozi, G., Ddaaki, W., Bazaale, J. M., Gray, R. H., Wawer, M. J., Reynolds, S. J., Kennedy, C. E., & Chang, L. W. (2017). Qualitative insights into implementation, processes, and outcomes of a randomized trial on peer support and HIV care engagement in Rakai, Uganda. BMC Infectious Diseases, 17(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-2156-0

- Nabitaka, V. M., Nawaggi, P., Campbell, J., Conroy, J., Harwell, J., Magambo, K., Middlecote, C., Caldwell, B., Katureebe, C., Namuwenge, N., Atugonza, R., Musoke, A., Musinguzi, J., & Torpey, K. (2020). High acceptability, and viral suppression of patients on dolutegravir-based first-line regimens in pilot sites in Uganda: A mixed-methods prospective cohort study. PLoS One, 15(5), e0232419. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232419

- National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA). (2019). Nigeria HIV/AIDS indicator and impact survey (NAIIS) south zone summary sheet. NACA. https://naca.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/NAIIS-SOUTH-SOUTH-ZONE-FACTSHEET_V0.9_030719-edits.pdf

- Nigeria Government. Nigeria country operational plan (COP). (2020). 2020 strategic direction summary. Abuja (Nigeria): Nigeria Government; 2020. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/COP-2020-Nigeria-SDS-Final-.pdf

- Odafe, S., Idoko, O., Badru, T., Aiyenigba, B., Suzuki, C., Khamofu, H., Onyekwena, O., Okechukwu, E., Torpey, K., & Chabikuli, O. N. (2012). Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics and level of care associated with lost to follow-up and mortality in adult patients on first-line ART in Nigerian hospitals. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 15(2), 17424. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.15.2.17424

- Oguntibeju, O. O. (2012). Quality of life of people living with HIV and AIDS and antiretroviral therapy. HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care, 4(4), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S32321

- Onoka, C. A., Uzochukwu, B. S., Onwujekwe, O. E., Chukwuka, C., Ilozumba, J., Onyedum, C., Nwobi, E. A., & Onwasigwe, C. (2012). Retention and loss to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in southeast Nigeria. Pathogens and Global Health, 106(1), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047773211Y.0000000018

- Penn, A. W., Azman, H., Horvath, H., Taylor, K. D., Hickey, M. D., Rajan, J., Negussie, E. K., Doherty, M., & Rutherford, G. W. (2018, December 14). Supportive interventions to improve retention on ART in people with HIV in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLoS One, 13(12), e0208814. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208814

- Pepfar Solutions Platform. (2018). Improving patient antiretroviral therapy retention through Community Adherence Groups in Zambia. https://www.pepfarsolutions.org/solutions/2018/1/16/decongesting-art-clinics-in-zambia-and-improving-patients-retention-through-community-adherence-groups-mrbtk

- Rubaihayo, J., Tumwesigye, N. M., & Konde-Lule, J. (2015). Trends in prevalence of selected opportunistic infections associated with HIV/AIDS in Uganda. BMC Infectious Diseases, 15(1), 187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0927-7

- Seifu, W., Ali, W., & Meresa, B. (2018). Predictors of loss to follow up among adult clients attending antiretroviral treatment at Karamara general hospital, Jigjiga town, Eastern Ethiopia, 2015: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Infectious Diseases, 18(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2892-9

- Shah, R., Watson, J., & Free, C. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis in the effectiveness of mobile phone interventions used to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV infection. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 915. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6899-6. PMID: 31288772; PMCID: PMC6617638.

- Stricker, S. M., Fox, K. A., Baggaley, R., Negussie, E., de Pee, S., Grede, N., & Bloem, M. W. (2014). Retention in care and adherence to ART are critical elements of HIV care interventions. AIDS and Behavior, 18(S5), 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0598-6

- Tadesse, K., & Haile, F. (2014). Predictors of loss to follow up of patients enrolled on antiretroviral therapy: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 5(5), 393. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6113.1000393

- Tiruneh, Y. M., Galárraga, O., Genberg, B., Wilson, I. B., & Thorne, C. (2016). Retention in care among HIV-infected adults in Ethiopia, 2005–2011: A mixed-methods study. PLoS One, 11(6), e0156619–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156619

- Webb, S., & Hartland, J. (2018). A retrospective notes-based review of patients lost to follow-up from anti-retroviral therapy at Mulanje mission hospital, Malawi. Malawi Medical Journal, 30(2), 73–78. https://doi.org/10.4314/mmj.v30i2.4