ABSTRACT

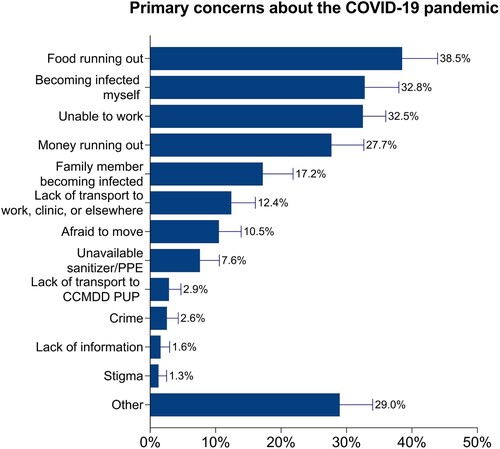

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions could adversely affect long-term HIV care. We evaluated the experiences of people receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) through a decentralized delivery program in South Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic. We telephoned a random subsample of participants enrolled in a prospective cohort study in KwaZulu-Natal in April and May 2020 and administered a semi-structured telephone interview to consenting participants. We completed interviews with 303 of 638 contacted participants (47%); 66% were female, with median age 36y. The most common concerns regarding the COVID-19 pandemic were food running out (121, 40%), fear of becoming infected with COVID-19 (103, 34%), and being unable to work/losing employment or income (102, 34%). Twenty-five (8%) participants had delayed ART pick-up due to the pandemic, while 212 (70%) had new concerns about ART access going forward. Mental health scores were worse during the pandemic compared to baseline (median score 65.0 vs 80.0, p < 0.001). Decentralized ART distribution systems have the potential to support patients outside of health facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic, but economic concerns and mental health impacts related to the pandemic must also be recognized and addressed.

Introduction

Concerns regarding potential impacts of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and associated restrictions on the HIV care continuum have been widespread. Disruptions in HIV testing (Lagat et al., Citation2020; Ponticiello et al., Citation2020), decreased rates of timely antiretroviral therapy (ART) collection (Kalichman et al., Citation2020; Pierre et al., Citation2020), and increased risk of ART discontinuation (Jiang et al., Citation2020) were reported worldwide early in the pandemic. During the initial national lockdown in South Africa, one province reported a 19.6% decrease in ART collection (Gauteng Province Department of Health, Citation2020). For South Africa, which has the largest population of people living with HIV (PLWH) and largest ART program in the world (UNAIDS, Citation2019), such interruptions in HIV care could be particularly detrimental. We hypothesized that the COVID-19 pandemic could have structural, economic, and psychosocial effects on PLWH engaged in care, contributing to interruptions in ART access. We evaluated the experiences of PLWH in a decentralized ART program in South Africa during the early COVID-19 pandemic, with a focus on concerns regarding COVID-19, ART access, and mental health.

Methods

Study population

We contacted a random subsample selected from 2,097 participants enrolled in an observational cohort study evaluating the Central Chronic Medicines Dispensing and Distribution (CCMDD) program in KwaZulu-Natal province (Bassett et al., Citation2022). CCMDD allows stable PLWH (not pregnant, on ART for ≥1 year, virologically suppressed) to collect ART at community-based pick-up points (e.g., private pharmacies, churches) (Steel, Citation2014). PLWH, age ≥18 years, meeting clinical criteria for CCMDD were eligible to enroll. Participants completed a baseline questionnaire at parent study enrollment. During the early COVID-19 pandemic, a telephonic questionnaire was administered to consenting participants. Interviews were conducted 28 April – 22 May 2020.

Parent study baseline data collection

The baseline questionnaire assessed demographic data, HIV care history, barriers to healthcare and competing needs in the preceding six months (Craw et al., Citation2008; Cunningham et al., Citation1999), mental health with the 5-item Mental Health Inventory test (higher scores indicating better mental health) (Berwick et al., Citation1991; Holmes, Citation1998) and social support with the 13-item Social Support Index (SSI) (McInerney et al., Citation2008; Sherbourne & Stewart, Citation1991).

COVID-19 pandemic data collection

The COVID-19 interview asked about concerns regarding COVID-19, missed or delayed ART pick-up, and perceived impacts on ART access. We re-assessed mental health and social support using a shortened, 4-item version of the mental health assessment and a condensed social support scale (Moser et al., Citation2012). For analysis, we combined several concerns regarding the COVID-19 pandemic into “economic” and “infection/illness” categories, and we combined several concerns regarding future ART pick-up into “infection” or “concrete barriers” categories.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to report baseline and COVID-era information. We used a Wilcoxon Signed Rank test to compare baseline and COVID-era mental health scores. The Wilcoxon Rank Sum and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for comparisons between groups. We used univariate logistic regression models to screen variables. Variables with p < 0.2 (two-sided) were included in multivariable logistic regression to assess predictors of concerns about ART access and of COVID-era mental health; age and sex were pre-specified in all models. All reported p-values were two-tailed.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Council of the University of KwaZulu-Natal and by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board (protocol 2017P001690).

Results

Participant characteristics

We contacted 638 enrollees, of whom 324 (51%) were unable to be reached, 11 (2%) declined the interview, and 303 (47%) completed the interview. A comparison of non-responders (not reached or declined) and responders is provided in Supplemental Table 1. Full participant demographics are shown in .

Table 1. Participant demographics. N = 303 unless otherwise stated.

Concerns regarding the COVID-19 pandemic

illustrates the most frequent concerns regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. Concerns about food running out (121, 40%) were most common.

New and anticipated barriers to ART access

Twenty-five participants (8%) had delayed ART pick-up due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 76 (25%) experienced a change in the ART pick-up process, and 212 (70%) identified new concerns about ART access going forward (). In adjusted analyses, participants enrolled in CCMDD for >12 months were less concerned about infection risk associated with ART pick-up, while participants with higher social support scores were more concerned about infection risk (). Participants who traveled >30 km to their ART pick-up points were more likely to be concerned about concrete barriers to ART access ().

Table 2. Barriers to ART access during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 3. Correlates of concerns about future ART access.

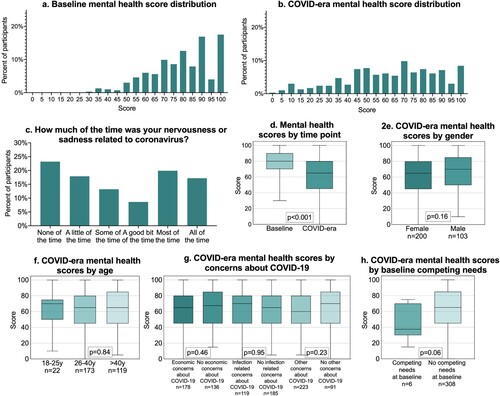

Mental health and social support

The median adapted mental health score worsened from 80.0 (IQR 70.0-90.0) at baseline to 65.0 (IQR 45.0–80.0) during the COVID-19 pandemic (p < 0.001) ((a, b, d)). Nearly half (45.7%) reported their nervousness or sadness was related to COVID-19 at least “a good bit of the time” (c). Mental health during COVID-19 did not differ by age, gender, concerns about COVID-19, or baseline competing needs ((e–h)). Median social support scores were 100 (maximum) at baseline and during the pandemic (data not shown).

Figure 2. Mental health at baseline and during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2a-2b. Distribution of scores on an adapted 4-item mental health instrument at enrollment into the parent study (baseline) and during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2c. Percentage of participants attributing feelings of nervousness or sadness to the COVID-19 pandemic. 2d. Comparison of median mental health scores at baseline and during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2e-2 h. Median mental health scores during the COVID-19 pandemic compared by subgroup.

Discussion

During the early COVID-19 pandemic period in South Africa, PLWH accessing ART through a decentralized program reported concerns about food and income security, fear of acquiring COVID-19 infection, and ART access going forward. Mental health scores were worse during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Food insecurity was the most common concern related to the pandemic. Food insecurity is common worldwide among PLWH (Anema et al., Citation2009), is associated with HIV care interruptions and decreased viral suppression (Aibibula et al., Citation2017), and has been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic (McLinden et al., Citation2020). Our results are consistent with a national survey in South Africa that identified high levels of food insecurity and concern about loss of income due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Human Sciences Research Council, Citation2020).

Relatively few participants delayed ART pick-up in the first months of the pandemic. Impacts on ART access may be attenuated in this cohort, who may have personal or social factors enabling ART adherence. In fact, social support, which has been associated with improved ART adherence (Kelly et al., Citation2014), was high in this cohort. The decentralized CCMDD program may also support ART continuity despite lockdown restrictions, as delayed ART pick-up in our cohort was lower than elsewhere in South Africa (Gauteng Province Department of Health, Citation2020) or Rwanda (Pierre et al., Citation2020) during a similar time-period. Nevertheless, most participants had concerns about ART access going forward, suggesting that, without additional support, the risk of missing ART could increase over the course of the pandemic.

Participants enrolled in CCMDD for >12 months were less likely to be concerned about infection risk impacting ART access, possibly reflecting greater trust in their ART pick-up points. Those with higher social support were more concerned about infection risk, which may reflect concern about infecting support networks or becoming a burden to others if they fall ill. Participants who travel >30 km to their pick-up points were more likely to report anticipated logistical barriers to ART access. This may indicate selection of a distant site close to a daily activity (e.g., workplace) that was restricted during the pandemic, and highlights vulnerabilities in existing patterns of HIV care access that can be disrupted during catastrophic events, such as severe shocks to the public health system.

Mental health scores in this cohort were worse during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychosocial effects of the pandemic on healthcare workers, patients, and the public have been widely documented, likely driven by a number of factors, including anxiety about infection, economic concerns, social isolation (Marziali et al., Citation2020), and increased interpersonal violence (Joska et al., Citation2020). There is an urgent need for innovations to ensure mental health and psychosocial support for PLWH in the case of future disruptions to the public health system.

Our results suggest that impacts on PLWH during the COVID-19 pandemic are multifactorial, including concerns about acquiring COVID-19 at points of care delivery, logistical barriers, mental health impacts, and competing needs such as food insecurity. Several strategies have been proposed to address these barriers. Differentiated HIV care delivery models (Wilkinson & Grimsrud, Citation2020), like CCMDD, have the potential to overcome transport barriers and safety concerns. Similarly, extended ART prescriptions could enable patients to avoid clinics for longer periods. Several of these strategies were employed or expanded during the pandemic (Grimsrud & Wilkinson, Citation2021), and detailed study of long-term effects on ART access and HIV outcomes will be critical to understand their impact.

This study was conducted during a one-month period spanning two levels of national lockdown in South Africa. We were unable to reach a significant proportion of participants, highlighting the challenges of transitioning to remotely administered research. Due to the short time-frame between institution of national lockdown and study start, some participants may not have been due for ART refills prior to the interview. The study was conducted among CCMDD participants; thus, the results cannot be generalized to PLWH not enrolled in a decentralized ART program, those not stable on ART, or to people without HIV. Further study of the long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on PLWH in South Africa as the pandemic progresses and levels of restrictions change is needed.

Meetings

This work was presented in part at the 2020 International AIDS Society Conference, July 6-10, 2020.

Sources of funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under grant number R01 MH114997 (IVB), K24 AI141036 (IVB), T32AI007433 (JJ), and by the Weissman Family MGH Research Scholar Award (IVB). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Research.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the dedication and efforts of the research team in Durban operating under difficult circumstances.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aibibula, W., Cox, J., Hamelin, A.-M., McLinden, T., Klein, M. B., & Brassard, P. (2017). Association between food insecurity and HIV viral suppression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 21(3), 754–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1605-5

- Anema, A., Vogenthaler, N., Frongillo, E. A., Kadiyala, S., & Weiser, S. D. (2009). Food insecurity and HIV/AIDS: Current knowledge, gaps, and research priorities. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 6(4), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-009-0030-z

- Bassett, I. V., Yan, J., Govere, S., Khumalo, A., Ngobese, N., Shazi, Z., Nzuza, M., Bunda, B. A., Wara, N. J., Stuckwisch, A., Zionts, D., Dube, N., Tshabalala, S., Bogart, L. M., & Parker, R. A. (2022). Uptake of community- versus clinic-based antiretroviral therapy dispensing in the central chronic medication dispensing and distribution program in South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 25(1), e25877. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25877

- Berwick, D. M., Murphy, J. M., Goldman, P. A., Ware, J. E., Barsky, A. J., & Weinstein, M. C. (1991). Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Medical Care, 29(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008

- Craw, J. A., Gardner, L. I., Marks, G., Rapp, R. C., Bosshart, J., Duffus, W. A., Rossman, A., Coughlin, S. L., Gruber, D., Safford, L. A., Overton, J., & Schmitt, K. (2008). Brief strengths-based case management promotes entry into HIV medical care: Results of the antiretroviral treatment access study-II. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 47(5), 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181684c51

- Cunningham, W., Anderson, R., Katz, M., Stein, M., Turner, B., Crystal, S., Zierler, S., Kuromiya, K., Morton, S., Clair, P., Bozzette, S., & Shapiro, M. (1999). The impact of competing subsistence needs and barriers on access to medical care for persons with human immunodeficiency virus receiving care in the United States. Medical Care, 37(12), 1270–1281. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199912000-00010

- Gauteng Province Department of Health. (2020). COVID-19 impacts on health services in Gauteng. https://www.gauteng.gov.za/Publications/9EF45838-3F76-45B4-880C-4948A04141A2.

- Grimsrud, A., & Wilkinson, L. (2021). Acceleration of differentiated service delivery for HIV treatment in sub-Saharan Africa during COVID-19. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 24(6), e25704. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25704

- Holmes, W. C. (1998). A short, psychiatric, case-finding measure for HIV seropositive outpatients: performance characteristics of the 5-Item mental health subscale of the SF-20 in a male, seropositive sample. MEDICAL CARE, 36(2), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199802000-00012

- Human Sciences Research Council. (2020). HSRC responds to the COVID-19 outbreak. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/11529/COVID-19%20MASTER%20SLIDES%2026%20APRIL%202020%20FOR%20MEDIA%20BRIEFING%20FINAL.pdf.

- Jiang, H., Zhou, Y., & Tang, W. (2020). Maintaining HIV care during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet HIV, 7(5), e308–e309. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30105-3

- Joska, J. A., Andersen, L., Rabie, S., Marais, A., Ndwandwa, E.-S., Wilson, P., King, A., & Sikkema, K. J. (2020). COVID-19: Increased risk to the mental health and safety of women living with HIV in South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 24(10), 2751–2753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02897-z

- Kalichman, S. C., Eaton, L. A., Berman, M., Kalichman, M. O., Katner, H., Sam, S. S., & Caliendo, A. M. (2020). Intersecting pandemics: Impact of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) protective behaviors on people living with HIV, Atlanta, Georgia. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 85(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002414

- Kelly, J. D., Hartman, C., Graham, J., Kallen, M. A., & Giordano, T. P. (2014). Social support as a predictor of early diagnosis, linkage, retention, and adherence to HIV care: Results from the steps study. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care : JANAC, 25(5), 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2013.12.002

- Lagat, H., Sharma, M., Kariithi, E., Otieno, G., Katz, D., Masyuko, S., Mugambi, M., Wamuti, B., Weiner, B., & Farquhar, C. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV testing and assisted partner notification services, Western Kenya. AIDS and Behavior, 24(11), 3010–3013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02938-7

- Marziali, M. E., Card, K. G., McLinden, T., Wang, L., Trigg, J., & Hogg, R. S. (2020). Physical distancing in COVID-19 may exacerbate experiences of social isolation among people living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 24(8), 2250–2252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02872-8

- McInerney, P. A., Ncama, B. P., Wantland, D., Bhengu, B. R., McGibbon, C., Davis, S. M., Corless, I. B., & Nicholas, P. K. (2008). Quality of life and physical functioning in HIV-infected individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Nursing & Health Sciences, 10(4), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2008.00410.x

- McLinden, T., Stover, S., & Hogg, R. S. (2020). HIV and food insecurity: A syndemic amid the COVID-19 pandemic. AIDS and Behavior, 24(10), 2766–2769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02904-3

- Moser, A., Stuck, A. E., Silliman, R. A., Ganz, P. A., & Clough-Gorr, K. M. (2012). The eight-item modified medical outcomes study social support survey: Psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 65(10), 1107–1116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.04.007

- Pierre, G., Uwineza, A., & Dzinamarira, T. (2020). Attendance to HIV antiretroviral collection clinic appointments during COVID-19 lockdown. A single center study in Kigali, Rwanda. AIDS and Behavior, 24(12), 3299–3301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02956-5

- Ponticiello, M., Mwanga-Amumpaire, J., Tushemereirwe, P., Nuwagaba, G., King, R., & Sundararajan, R. (2020). “Everything is a mess”: How COVID-19 is impacting engagement with HIV testing services in rural southwestern Uganda. AIDS and Behavior, 24(11), 3006–3009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02935-w

- Sherbourne, C. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine, 32(6), 705–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B

- Steel, G. (2014, April 14). Alternative chronic medicine access programme for public sector patients. Civil society stakeholder meeting. https://www.differentiatedcare.org/Portals/0/adam/Content/5zkRswkhdUCwztOtMVmPKg/File/DOH_CCMDD%20civil%20society%20presentation_20140512_TO%20MSF.pdf.

- UNAIDS. (2019). UNAIDS data 2019: South Africa. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica.

- Wilkinson, L., & Grimsrud, A. (2020). The time is now: Expedited HIV differentiated service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23(5), e25503. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25503