ABSTRACT

HIV prevention for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) and transgender women (TGW) is critical to reducing health disparities and population HIV prevalence. To understand if different types of stigma impact engagement with HIV prevention services, we assessed associations between stigmas and use of HIV prevention services offered through an HIV prevention intervention. This analysis included 201 GBMSM and TGW enrolled in a prospective cohort offering a package of HIV prevention interventions. Participants completed a baseline survey that included four domains of sexual identity/behavior stigma, HIV-related stigma, and healthcare stigma. Impact of stigma on PrEP uptake and the number of drop-in visits was assessed. No domain of stigma was associated with PrEP uptake. In bivariate analysis, increased enacted sexual identity stigma increased number of drop-in visits. In a logistic regression analysis constrained to sexual identity stigma, enacted stigma was associated with increased drop-in visits (aIRR = 1.30, [95% CI: 1.02, 1.65]). Participants reporting higher enacted stigma were modestly more likely to attend additional services and have contact with the study clinics and staff. GBMSM and TGW with higher levels of enacted stigma may seek out sensitized care after negative experiences in their communities or other healthcare settings.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) and transgender women (TGW) are globally disproportionately affected by HIV (Beyrer et al., Citation2012; Stannah et al., Citation2019) with HIV prevalence consistently higher among GBMSM and TGW than other adults across international settings (Beyrer et al., Citation2013; Stannah et al., Citation2019). While relatively fewer studies have reported HIV outcomes at later stages of the HIV treatment cascade, a meta-analysis of data after 2011 found the pooled proportion of GBMSM in Africa that were aware of their positive HIV status was low (18.5%)(Stannah et al., Citation2019). HIV prevention for GBMSM and TGW is critical to reducing health disparities experienced by GBMSM and TGW and for decreasing overall population HIV prevalence. This is particularly relevant in settings like South Africa, where HIV prevalence is 19% among the adult population and estimated to be as high as 22–48% among GBMSM (AVERT, Citation2017).

Several proven prevention methods aimed at behavioral change and biomedical intervention, such as condoms, pre-exposure prophylaxis, and treatment as prevention, are core components of HIV prevention strategies; however, mathematical models demonstrate that under realistic scenarios of scale-up, no single one of these method alone is sufficient to reduce incident HIV infections to a level that would bring an end to the epidemic (Bekker et al., Citation2012; Sullivan et al., Citation2012). Therefore, researchers and practitioners have become increasingly interested in measuring and reducing the impact of social determinants that increase vulnerability to HIV, such as stigma, poverty, and human rights violations, which could facilitate uptake of each of these interventions (Auerbach et al., Citation2011; Sullivan et al., Citation2012; Verboom et al., Citation2018). Stigma occurs when an individual or group of individuals possess a socially devalued identity (Brewis et al., Citation2020; Crocker et al., Citation1998) For GBMSM and TGW who often identify with one or multiple stigmatized identities, the consequences of stigma can have physical and mental health implications (Beyrer et al., Citation2013; Fay et al., Citation2011). Researchers have called for more robust evidence on intersectional stigma and methods for stigma reduction among people living with HIV and key populations (Andersson et al., Citation2020).

Uptake of HIV prevention services and care is often low among GBMSM and TGW in settings where same-sex behavior is strongly rejected by traditional, cultural, and community values (Sullivan et al., Citation2012). Despite strong legal protections in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa for expressing one’s sexual and gender identity, GBMSM and transgender women in South Africa still report experiences of homophobia (sexual identity stigma) and discrimination (Hassan et al., Citation2018; Tucker et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, many GBMSM and TGW experience intersectional stigmas, or the convergence of multiple stigmatized identities, which can have greater than additive negative effects on health and wellbeing (Crenshaw, Citation1991; Fitzgerald-Husek et al., Citation2017; Turan et al., Citation2019). Particularly, due to both the higher prevalence of HIV among GBMSM and TGW and negative social attitudes and assumptions regarding GBMSM in South Africa, many GBMSM and TGW often also face HIV-related stigma (Cloete et al., Citation2008). A study of GBMSM living with HIV in Cape Town found that overall this cohort of men experienced more discrimination than their non-GBMSM counterparts living with HIV (Cloete et al., Citation2008; Peltzer & Pengpid, Citation2019), demonstrating how devalued identities can intersect, heightening risk for negative outcomes (Earnshaw et al., Citation2013). HIV-related stigma and sexual identity and/or behavior stigma have both been shown to decrease engagement with HIV treatment and prevention services, ultimately restricting progress towards reductions in HIV disparities and outcomes (Earnshaw & Chaudoir, Citation2009; Parker & Aggleton, Citation2003; Reinius et al., Citation2017; Schwartz et al., Citation2015).

To understand the potential influence of stigma on HIV prevention engagement, this study aimed to determine the associations between stigmas (sexual identity/behavior and HIV-related) at baseline and subsequent engagement with HIV prevention services (PrEP uptake and prevention visits attended) offered during the HIV prevention project’s 12-month implementation period. This pilot study will help elucidate how stigma may act as a barrier to HIV prevention engagement and importantly, the directionality of the associations for specific domains of stigma. This understanding will ultimately inform targeted, domain-specific stigma reduction strategies to improve engagement with HIV services and decrease disparities in HIV among GBMSM and TGW.

Methods

Cohort sampling and design

Study data come from a 12-month prospective cohort of GBMSM and TGW in South Africa, the Sibanye Health Project (SHP), which has been previously described (McNaghten et al., Citation2014). Briefly, 185 GBMSM and 16 TGW were enrolled at baseline and offered a package of HIV prevention interventions at each study visit and during optional drop-in visits in between including condom choices with an assortment of styles, sizes, and features; condom-compatible lubricant choices, including water- and silicone-based types, HIV prevention counseling, couples HIV testing and counseling (CHTC), and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for eligible men and TGW. The package also included community-level interventions to improve health literacy and uptake of prevention services by GBMSM and TGW. This included training of health care providers and clinic staff on providing care sensitive to the needs of LGBT populations, including provision of sexual health services and risk-reduction counseling to GBMSM. The baseline survey completed by participants also included a stigma questionnaire, which included multiple domains of sexual identity and behavior stigma (enacted, orientation concealment, anticipated, and internalized) and HIV-related stigma. Participants completed regular study visits at baseline, month three, month six, and conclusion of the study (12 months). Eligible men were male at birth, aged 18 years and older, self-reported that they had anal intercourse with a man in the past year, were current residents of the study sites of Cape Town or Port Elizabeth, were willing to provide contact information, and had a phone for purposes of study follow-up. Participants were recruited at community events and venues, online, and by participant referral. Most (83%) of the cohort was HIV negative at baseline. By design the study recruited at baseline 20% HIV positive participants, so that HIV status could not be inferred by study participation.

Study measures

All participants completed a baseline survey that included the Multidimensional Sexual Identity Stigma (MSIS) Scale (Brown et al., Citation2021). The MSIS was validated for use with GBMSM and TGW (Appendix A) and included four domains of sexual identity/behavior stigma (enacted, concealment orientation, anticipated, and internalized). The stigma assessment also included HIV-related stigma (an HIV attitudes and discrimination scale administered to HIV negative participants) and a healthcare stigma domain (Bunn et al., Citation2007; Earnshaw & Chaudoir, Citation2009; Visser et al., Citation2008). Summary scores for all four domains of sexual identity stigma and the healthcare stigma domain were created by taking an average response of all items included in a domain, similar methods have been used elsewhere (Lysaker et al., Citation2007; Williams et al., Citation2020). Additionally, summary scores were generated by converting the sum of Likert values for all variables in a domain into percent of maximum possible (POMP) score (Cohen et al., Citation1999). If participants did not answer more than 25% of variables in a domain, the overall POMP score for that domain was reported as missing because individual item missingness can cause substantial challenges with study power (Mazza et al., Citation2015). We performed a sensitivity analysis, relative to including all study data, and found that this study design choice did not substantially alter study results. POMP scores were calculated using the maximum possible score per domain. POMP scores were used in graphics comparing the four domains to standardize the scales, the range of which were different between some of the domains due to structuring of the Likert scales. HIV-related stigma was calculated as the mean Likert value of five questions about negative attitudes held towards people living with HIV. The two primary outcomes for this study were metrics assessing the degree of engagement with the intervention: PrEP uptake and the number of drop-in visits completed. PrEP uptake was measured dichotomously as either being on PrEP at study completion (12-months) or not (yes, no), which was self-reported to study staff at last study visit. A second outcome regarding PrEP uptake was measured as ever started PrEP during the study period (yes, no). PrEP was offered at multiple study visits to eligible participants. Additionally, optional drop-in visits were available at any time for participants to receive counseling, HIV or STI testing, condoms, and lube. The more participants attended optional drop-in visits (coded as a count of drop-in visits attended) the more they had the ability to access additional prevention services and goods, but also spent more time engaging with culturally competent clinic staff.

Analytic methods

Descriptive analyses assessed participant demographics and average value of stigma for all domains as a measure of central tendency. A correlation matrix including the four sexual identity/behavior domains created. To assess the association of baseline stigma with PrEP uptake, two models were used. Model 1 estimated the association of baseline sexual identity stigma and HIV-related stigma with being on PrEP at the end of the study (yes = 1; no = 0) using a logistic regression, and Model 2 examined the association of baseline sexual identity stigma and HIV-related stigma with ever starting PrEP during the study (yes = 1; no = 0) using a logistic regression. Two different PrEP outcome models were analyzed because some participants may have started and stopped due to side effects or other barriers but still had the protection provided by PrEP during part of the intervention period. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR, aOR) for two measurements of PrEP uptake by baseline sexual identity stigma and HIV-related stigma domains (Models 1 and 2) were analyzed using logistic regression using Stata/SE 14.2 (College Station, TX). Potential confounders were factors established in the literature to be associated with stigma and HIV prevention engagement including: any drug use in the past 6 months (Flickinger et al., Citation2013; Tobias et al., Citation2007), outness to a healthcare provider (Axelrad et al., Citation2013; Ayala et al., Citation2014, Citation2013; Lyons et al., Citation2019), pre-intervention involvement with an LGBT community organization (Ayala et al., Citation2014, Citation2013), and baseline likeliness to start PrEP (likely associated with actual PrEP uptake and those with higher stigma may be less willing to access service such as PrEP). Model selection was done using a backwards change in estimate approach whereby covariates were excluded one at a time if removing them from the model did not change the exposure estimates by more than 10% in either direction, and the model was constrained to retain the four exposure domains of sexual identity stigma (enacted, orientation concealment, anticipated, and internalized) and the HIV-related stigma exposure. Pearson’s goodness of fit statistics were used as a secondary assessment of model fit.

To assess the association of baseline sexual stigma and HIV-related stigma with the number of drop-in visits completed, a third model was used. Unadjusted and adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR, aIRR) completed with the four domains of sexual identity stigma and HIV-related stigma as exposure variables were calculated using negative binomial regression, with number of drop-in visits as the outcome. Negative binomial regression can provide incidence rate ratio output due to the difference between the log of expected counts being equal to the log of their quotient; as all participants had equal follow-up time, this measure indicates the “rate” of drop-in visits over 12 months, contributing to the incidence rate ratio. All participants were eligible for drop-in visits during the same 12-month intervention period. A likelihood ratio test indicated significant over dispersion, indicating negative binomial regression to be favorable over Poisson regression. The potential confounders were the same as used for Models 1 and 2. Model selection was done using a backwards change in estimate approach, constraining the model to retain the four exposure domains of sexual identity stigma (enacted, orientation concealment, anticipated, and internalized).

Ethics

Institutional review board approval was obtained by Emory University, Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation (DTHF), the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), and the National Health Laboratory Service prior to implementation of study activities. The project was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (1R01A1094575), with supplemental funding provided by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U23GGH000258). Approval from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, Division of AIDS, Prevention Sciences Review Committee was obtained prior to initiation of study procedures.

Results

Study demographics and covariates are described in . Participants were predominantly Black African (81.9%), homosexual (58.4%) or bisexual (32.5%), male-identifying (91.8%), and not married (95.4%). Most participants were unemployed (67.0%) and reported no annual income (52.7%).

Table 1. Baseline participant demographics of 201 participants in SHP cohort, Cape Town and Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 2015–2016.

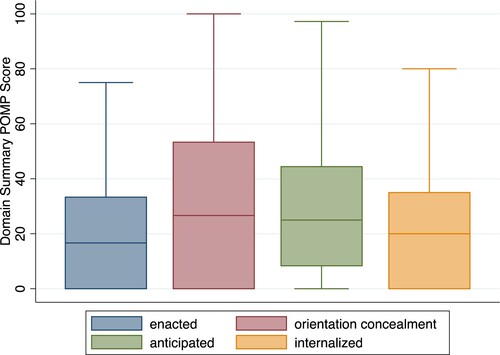

Baseline sexual identity stigma is shown summarized in . Sexual identity stigma scores were fairly similar across domains, with orientation concealment being the highest percent of maximum possible score.

Figure 1. Box plots of baseline sexual identity/behavior stigma domains of 201 men who have sex with men and transgender women, Cape Town and Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 2015–2016.

All four domains of sexual identity stigma were positively correlated with one another except for enacted stigma and orientation concealment, however pairwise correlation between domains did not exceeded 0.34 for any two domains ().

Table 2. Correlation matrix and pvalues for baseline sexual identity stigma domains among 201 men who have sex with men and transgender women, Cape Town and Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 2015–2016

Compared to gay-identifying participants, bisexual GBMSM reported lower levels of enacted stigma (OR = 0.42, [95% CI: 0.24, 0.72]), higher orientation concealment (OR = 3.37 [95% CI: 2.35, 4.85]), and higher internalized stigma (OR = 1.54, [95% CI: 1.12, 2.14]) in bivariate analyses. Relatively few participants identified as a transgender woman (n = 7) or female (n = 9).

Sexual identity stigma and HIV-related stigma on PrEP uptake

None of the potential confounding variables were retained in the models after the change in estimate model selection approach was conducted, because none of the variables when removed led to a greater than 10% change in estimate of any stigma domain. A sub-analysis constraining PrEP likeliness to remain in the model due to likely importance of this factor on actual PrEP uptake yielded similar results. No domain of stigma was associated with PrEP uptake measured either as being on PrEP at the end of the study (Model 1) or ever enrolling on PrEP during the study (Model 2); see .

Table 3. Associations of baseline sexual identity stigma domains and HIV-related stigma on PrEP uptake among 201 men who have sex with men and transgender women, Cape Town and Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 2015–2016.

Sexual identity stigma and HIV-related stigma on drop-in visits completed

After backwards change in estimate approach was completed, no confounders remained in Model 3 (with four sexual identity stigma domains and HIV-related stigma). None of the domains of sexual identity stigma or HIV-related stigma was associated with the number of drop-in visits completed at the alpha = 0.05 level, however a positive correlation was seen for enacted stigma. (). In bivariate analysis, increased enacted sexual identity stigma slightly increased number of drop-in visits. Additionally, in a sub-analysis where the model was constrained to only the sexual identity stigma domains (HIV-related stigma was dropped from the model), enacted stigma was associated with an increased number of drop-in visits (aIRR = 1.30, [95% CI: 1.02, 1.65]). This indicates that a one-point increase of average enacted stigma variable response on the Likert scale was associated with a modest increase in the number of drop-in visits.

Table 4. Associations of baseline sexual identity stigma domains and HIV-related stigma on number of drop-in visits completed in Sibanye Health Project among 201 men who have sex with men and transgender women, Cape Town and Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 2015–2016.

Discussion

Within the context of a study providing a package of HIV prevention interventions to GBMSM and TGW in South Africa, we sought to identify the associations of multiple types of baseline stigmas on engagement with HIV prevention services. In this study none of the measured domains of sexual identity stigma or HIV-related stigma were associated with PrEP uptake; the decision of whether or not to start and continue PrEP is likely the result of a larger set of social and contextual factors. Similarly, neither HIV-related stigma nor most of the sexual identity stigma domains was associated with the number of drop-in visits.

Our results indicating that stigma was not associated with PrEP uptake were unexpected. Stigma, particularly HIV-related stigma (e.g., Fear that sexual partners or family/friends will think they are living with HIV due to PrEP use), has been described by others as a barrier to PrEP uptake (Biello et al., Citation2017; Franks et al., Citation2018; Goparaju et al., Citation2017; Haire, Citation2015; Irungu & Baeten, Citation2020). In this setting, as in others, there are likely a multitude of factors influencing PrEP uptake and use (Sullivan et al., Citation2019), the influence of which may outweigh the impact of stigma. Additionally, other forms of stigma such as PrEP-stigma that were not measured here may be more of an influence and should be investigated on future research (Siegler et al., Citation2020). Negative HIV-related attitudes were not associated with PrEP uptake. However, the HIV-attitudes domain captured the participant’s beliefs relating to HIV rather than measuring broader community and societal beliefs on HIV, which may be the driving factor as has been found in other settings (Dubov et al., Citation2018; Franks et al., Citation2018). Additionally, GBMSM with the highest degree of stigma are likely missing from this and all data due to difficulty recruiting those with high levels of orientation concealment. Those with the highest degree of orientation concealment are less likely engaged in GBMSM-specific care at all (Lorway et al., Citation2014; Taegtmeyer et al., Citation2013), and therefore would likely not have been enrolled in this study. This finding may also indicate that repeated offers of PrEP could be overcoming the negative effects of stigma, but future research would be needed to further understand this hypothesized relationship.

Enacted stigma was the only domain associated with a higher number of drop-in visits. In this study, participants reporting higher enacted stigma were modestly more likely to attend additional services and have contact with the study clinics and staff. This finding highlights the importance of spaces and providers offering culturally competent care, because GBMSM and TGW with higher levels of enacted stigma may seek out sensitized care after negative experiences in their communities or other healthcare settings. Non-sensitized healthcare providers can increase the risk of a patient experiencing enacted stigma in healthcare settings and therefore spaces with culturally competent staff should be expanded, easily accessible, and can be leveraged to provide services to LGBTQ people experiencing stigma. These spaces can offer stigma reduction and HIV services and may be critical points of contact for hard to reach populations. The null findings for the other domains of stigma and drop-in visits could be because the men and TGW in this study already had greater social involvement with LGBT organizations and spaces before the study (e.g., Selection bias); GBMSM who were not engaged with culturally competent care might have been more impacted by experiences of stigma as higher levels of health agency, connectedness with community groups, and social capital have been reported to decrease the impact of some types of stigma on engagement with care (Campbell et al., Citation2013; Cange et al., Citation2015; Zhang et al., Citation2017) and our study participants may represent those who are more connected to LGBT community spaces. This hypothesis is supported by their recruitment from events, venues, and study clinics. Future research should include, as much as possible, the most marginalized GBMSM and TGW to understand barriers to HIV prevention and care engagement and to link them with culturally competent care. Potential ways to identify and enroll marginalized GBMSM and TGW include sampling techniques like respondent-driven sampling and through recruitment at GBMSM and TGW hotspots.

Orientation concealment was the most commonly reported sexual identity stigma, and stigma in the domains of enacted, anticipated, and internalized was similar across participants. Orientation concealment was more common for bisexual men than those identifying as gay; this is a logical association because relationships with women could decrease visibility of their sexual identity. These data are consistent with other literature showing higher concealment among bisexual individuals (Chan et al., Citation2020; Schrimshaw et al., Citation2018). Orientation concealment has been found to be associated with lower life satisfaction (Pachankis & Bränström, Citation2018), depressive symptoms (Ding et al., Citation2019), lower self-worth (Camacho et al., Citation2020; Frable et al., Citation1998), higher levels of stress biomarkers (Huebner & Davis, Citation2005). Additionally, previous literature shows that bisexual men may avoid sexual orientation disclosure as a stigma management strategy (Schrimshaw et al., Citation2018). Due to the negative effects of orientation concealment, it is important to consider differences in identity among GBMSM in stigma research, because bisexual men have different experiences of stigma than gay men and other men who have sex with men. Future stigma reduction interventions should consider tailoring specific services to bisexual men to reduce the negative impacts of binegativity and to address differences in sexual risk behaviors been bisexual men versus gay and other MSM (Torres et al., Citation2019). In addition, although the number of transgender women in this sample was relatively small (n = 16 combining those who identified as transgender and as female; the study only enrolled individuals who reported male sex at birth), the stigma experiences of these women were higher in all domains except for orientation concealment. These data and other data from sub-Saharan Africa have shown that transgender women are often more visible in society compared to gender conforming men, which can increase their susceptibility to discrimination, stigma, and abuse (Lyons et al., Citation2019; Scheim et al., Citation2019). Again, this highlights the importance of tailoring interventions not only to GBMSM but also to transgender women due to differences in stigma and discrimination and the need for targeted stigma reduction interventions for these women.

This study has some limitations. Because this was a pilot study that was not powered for the stigma scales, the sample size is relatively small for assessment of stigma outcomes, and future large-scale longitudinal stigma research should be powered to confirm or refute these findings. Although this study enrolled 16 participants who identified as either transgender or female, this analysis did not explicitly measure stigma relating to gender identity. The study design of the Sibanye Health Project also limits some of the interpretation of findings, particularly for PrEP uptake: all study participants came for regular study visits every three months, and were offered PrEP if they had not already enrolled in PrEP. In a different setting without regular receipt of care and offers of PrEP, sexual identity stigma might have been associated with PrEP uptake. Research in cohorts with less structured care offerings is needed to assess this possibility. Additionally, stigma and other social drivers have been difficult to map onto biological HIV outcomes (Auerbach et al., Citation2011), and mediating factors such as mental health and substance use are necessary to full characterize the pathways through which stigma impacts health. However, in the Sibanye Health Project pilot study, the only mental health indicator was a question asking if participants had received mental health services in the past 12 months. Only three participants had received some sort of mental health service, which likely is a manifestation of low availability of and access to these services in their local communities rather than an assessment of needs for mental health services. Future research should include more detailed data on mental health, stress, and social support, as these likely play an important role in mediating the effects of stigma onto biological outcomes (Pachankis & Bränström, Citation2018; Rodriguez-Hart et al., Citation2017; Wei et al., Citation2016). Indeed, one study of GBMSM in Cape Town conducted a path analysis and found depression and self-efficacy may mediate the effect of homophobic stigma on unprotected anal intercourse (Tucker et al., Citation2014). The collection of such data is therefore an important step in fully characterizing these causal pathways. Additionally, those with highest levels of stigma may not be included in this study, because these GBMSM are likely harder to access and recruit.

Despite these limitations, these data present important findings about sexual identity stigma and HIV-related stigma among GBMSM and transgender women in South Africa. Safe spaces offering culturally competent care for LGBTQ people can be used as important points of connection for those facing stigma, and stigma reduction strategies should be specially targeted to the diverse groups they aim to serve. Additionally, this research outlines important next steps in the field of stigma research, and the need for robust measurement of potential mediating factors of the impact of stigma on HIV prevention engagement. By increasing the engagement of GBMSM and TGW with HIV prevention services and access to non-stigmatizing clinics and community spaces, improvements in HIV care, outcomes, and disparities for GBMSM and transgender women can be realized.

summarizes baseline percentage of maximum possible scores for enacted stigma (25th percentile = 0.0, 50th percentile = 16.7, 75th percentile = 33.3), orientation concealment (25th percentile = 0.0, 50th percentile = 26.7, 75th percentile = 53.3), anticipated stigma (25th percentile = 8.3, 50th percentile = 25.0, 75th percentile = 44.4), and internalized stigma (25th percentile = 0.0, 50th percentile = 20.0, 75th percentile = 35.0).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andersson, G. Z., Reinius, M., Eriksson, L. E., Svedhem, V., Esfahani, F. M., Deuba, K., Rao, D., Lyatuu, G. W., Giovenco, D., & Ekström, A. M. (2020). Stigma reduction interventions in people living with HIV to improve health-related quality of life. The Lancet HIV, 7(2), e129–e140. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30343-1

- Auerbach, J. D., Parkhurst, J. O., & Cáceres, C. F. (2011). Addressing social drivers of HIV/AIDS for the long-term response: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Global Public Health, 6(SUPPL. 3), S293–S309. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2011.594451

- AVERT. (2017). HIV and AIDS in South Africa | AVERT. Retrieved April 12, 2017, from https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/south-africa

- Axelrad, J. E., Mimiaga, M. J., Grasso, C., & Mayer, K. H. (2013). Trends in the spectrum of engagement in HIV care and subsequent clinical outcomes among men who have sex with men (MSM) at a Boston community health center. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 27(5), 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2012.0471

- Ayala, G., Makofane, K., Santos, G.-M., Arreola, S., Herbert, P., Thomann, M., Wilson, P., Beck, J., & Do, T. (2014). HIV treatment cascades that leak: Correlates of drop-off from the HIV care continuum among men who have sex with men worldwide. AIDS & Clinical Research, 5(8), https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6113.1000331

- Ayala, G., Makofane, K., Santos, G.-M., Beck, J., Do, T., Hebert, P., Wilson, P. A., Pyun, T., & Arreola, S. (2013). Access to basic HIV-related services and PrEP acceptabilityamong men who have sex with men worldwide: Barriers,facilitators, and implications for combination prevention. Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/953123

- Bekker, L. G., Beyrer, C., & Quinn, T. C. (2012). Behavioral and biomedical combination strategies for HIV prevention. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 2(8), a007435–a007435. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a007435

- Beyrer, C., Baral, S. D., van Griensven, F., Goodreau, S. M., Chariyalertsak, S., Wirtz, A. L., & Brookmeyer, R. (2012). Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. The Lancet, 380(9839), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6

- Beyrer, C., Sullivan, P., Sanchez, J., Baral, S. D., Collins, C., Wirtz, A. L., Altman, D., Trapence, G., & Mayer, K. (2013). The increase in global HIV epidemics in MSM. AIDS, 27(17), 2665–2678. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000432449.30239.fe

- Biello, K. B., Oldenburg, C. E., Mitty, J. A., Closson, E. F., Mayer, K. H., Safren, S. A., & Mimiaga, M. J. (2017). The “Safe Sex” conundrum: Anticipated stigma from sexual partners as a barrier to PrEP use among substance using MSM engaging in transactional sex. AIDS and Behavior, 21(1), 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1466-y

- Brewis, A., Wutich, A., & Mahdavi, P. (2020). Stigma, pandemics, and human biology: Looking back, looking forward. American Journal of Human Biology, 32(5), e23480. https://doi.org/10.1002/AJHB.23480

- Brown, C. A., Sullivan, P. S., Stephenson, R., Baral, S. D., Bekker, L.-G., Phaswana-Mafuya, N. R., Simbayi, L. C., Sanchez, T., Valencia, R. K., Zahn, R. J., & Siegler, A. J. (2021). Developing and validating the multidimensional sexual identity stigma scale among men who have sex with men in South Africa. Stigma and Health, 6(3), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000294

- Bunn, J. Y., Solomon, S. E., Miller, C., & Forehand, R. (2007). Measurement of stigma in people with HIV: A reexamination of the HIV stigma scale. AIDS Education and Prevention, 19(3), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2007.19.3.198

- Camacho, G., Reinka, M. A., & Quinn, D. M. (2020). Disclosure and concealment of stigmatized identities. Current Opinion in Psychology, 31, 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.031

- Campbell, C., Scott, K., Nhamo, M., Nyamukapa, C., Madanhire, C., Skovdal, M., Sherr, L., & Gregson, S. (2013). Social capital and HIV competent communities: The role of community groups in managing HIV/AIDS in rural Zimbabwe. AIDS Care, 25(SUPPL.1), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2012.748170

- Cange, C., LeBreton, M., Billong, S., Saylors, K., Tamoufe, U., Papworth, E., Yomb, Y., & Baral, S. (2015). Influence of stigma and homophobia on mental health and on the uptake of HIV/sexually transmissible infection services for Cameroonian men who have sex with. Sexual Health, 12(4), 315–321. http://www.publish.csiro.au/sh/SH15001 https://doi.org/10.1071/SH15001

- Chan, R. C. H., Operario, D., & Mak, W. W. S. (2020). Bisexual individuals are at greater risk of poor mental health than lesbians and gay men: The mediating role of sexual identity stress at multiple levels. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.020

- Cloete, A., Simbayi, L. C., Kalichman, S. C., Strebel, A., & Henda, N. (2008). Stigma and discrimination experiences of HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care, 20(9), 1105–1110. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120701842720

- Cohen, P., Cohen, J., Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1999). The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 34(3), 315–346. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327906MBR3403_2

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Crocker, J., Major, B., Steele, C., Gilbert, D. T., Fiske, S. T., & Lindzey, G. (1998). The handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2). https://books.google.com/books?hl = en&lr = &id = -4InWCsra7IC&oi = fnd&pg = PR13&dq = The+Handbook+of+Social+Psychology:+2-Volume+Set&ots = h9qHZRZlsa&sig = Kez-jnLiTOPYz_mv_F2Ir9Ii6Zw#v = onepage&q&f = false

- Ding, C., Chen, X., Wang, W., Yu, B., Yang, H., Li, X., Deng, S., Yan, H., & Li, S. (2019). Sexual minority stigma, sexual orientation concealment, social support and depressive symptoms among men who have sex with men in China: A moderated mediation modeling analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 260, 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02713-3

- Dubov, A., Galbo, P., Altice, F. L., & Fraenkel, L. (2018). Stigma and shame experiences by MSM Who take PrEP for HIV prevention: A qualitative study. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(6), 1843–1854. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988318797437

- Earnshaw, V. A., & Chaudoir, S. R. (2009). From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: A review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS and Behavior, 13(6), 1160–1177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3

- Earnshaw, V. A., Smith, L. R., Chaudoir, S. R., Amico, K. R., & Copenhaver, M. M. (2013). HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: A testof the HIV stigma framework. AIDS and Behavior, 17(5), 1785–1795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9

- Fay, H., Baral, S. D., Trapence, G., Motimedi, F., Umar, E., Iipinge, S., Dausab, F., Wirtz, A., & Beyrer, C. (2011). Stigma, health care access, and HIV knowledge among men who have sex with men in Malawi, Namibia, and Botswana. AIDS and Behavior, 15(6), 1088–1097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9861-2

- Fitzgerald-Husek, A., Van Wert, M. J., Ewing, W. F., Grosso, A. L., Holland, C. E., Katterl, R., Rosman, L., Agarwal, A., & Baral, S. D. (2017). Measuring stigma affecting sex workers (SW) and men who have sex with men (MSM): A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 12(11), https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0188393

- Flickinger, T. E., Saha, S., Moore, R. D., & Beach, M. C. (2013). Higher quality communication and relationships are associated with improved patient engagement in HIV care. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 63(3), 362–366. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e318295b86a

- Frable, D. E. S., Platt, L., & Hoey, S. (1998). Concealable stigmas and positive self-perceptions: Feeling better around similar others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(4), 909–922. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.4.909

- Franks, J., Hirsch-Moverman, Y., Loquere, A. S., Amico, K. R., Grant, R. M., Dye, B. J., Rivera, Y., Gamboa, R., & Mannheimer, S. B. (2018). Sex, PrEP, and stigma: Experiences with HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among New York city MSM participating in the HPTN 067/ADAPT study. AIDS and Behavior, 22(4), 1139–1149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1964-6

- Goparaju, L., Praschan, N. C., Jeanpiere, L. W., Experton, L. S., Young, M. A., & Kassaye, S. (2017). Stigma, partners, providers and costs: Potential barriers to PrEP uptake among US women. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 08(09), 730. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6113.1000730

- Haire, B. G. (2015, October 13). Preexposure prophylaxis-related stigma: Strategies to improve uptake and adherence –a narrative review. HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care. Dove Medical Press Ltd. https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S72419

- Hassan, N. R., Swartz, L., Kagee, A., De Wet, A., Lesch, A., Kafaar, Z., & Newman, P. A. (2018). “There is not a safe space where they can find themselves to be free”: (Un)safe spaces and the promotion of queer visibilities among township males who have sex with males (MSM) in Cape Town, South Africa. Health & Place, 49, 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.11.010

- Huebner, D. M., & Davis, M. C. (2005). Gay and bisexual men who disclose their sexual orientations in the workplace have higher workday levels of salivary cortisol and negative affect. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 30(3), 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3003_10

- Irungu, E. M., & Baeten, J. M. (2020). PrEP rollout in Africa: Status and opportunity. Nature Medicine, 26(5), 655–664. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-0872-x https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0872-x

- Lorway, R., Thompson, L. H., Lazarus, L., du Plessis, E., Pasha, A., Fathima Mary, P., Khan, S., & Reza-Paul, S. (2014). Going beyond the clinic: Confronting stigma and discrimination among men who have sex with men in Mysore through community-based participatory research. Critical Public Health, 24(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2013.791386

- Lyons, C., Stahlman, S., Holland, C., Ketende, S., Van Lith, L., Kochelani, D., Mavimbela, M., Sithole, B., Maloney, L., Maziya, S., & Baral, S. (2019). Stigma and outness about sexual behaviors among cisgender men who have sex with men and transgender women in eswatini: A latent class analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases, 19(211), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3711-2

- Lysaker, P. H., Davis, L. W., Warman, D. M., Strasburger, A., & Beattie, N. (2007). Stigma, social function and symptoms in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: Associations across 6 months. Psychiatry Research, 149(1–3), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2006.03.007

- Mazza, G. L., Enders, C. K., & Ruehlman, L. S. (2015). Addressing item-level missing data: A comparison of proration and full information maximum likelihood estimation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(5), 519. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2015.1068157

- McNaghten, A., Kearns, R., Siegler, A. J., Phaswana-Mafuya, N., Bekker, L.-G., Stephenson, R., Baral, S. D., Brookmeyer, R., Yah, C. S., Lambert, A. J., & Sullivan, P. S. (2014). Sibanye methods for prevention packages program project protocol: Pilot study of HIV prevention interventions for men who have sex with men in South Africa. JMIR Research Protocols, 3(4), e55. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.3737

- Pachankis, J. E., & Bränström, R. (2018). Hidden from happiness: Structural stigma, sexual orientation concealment, and life satisfaction across 28 countries. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(5), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000299

- Parker, R., & Aggleton, P. (2003). HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine, 57(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00304-0

- Peltzer, K., & Pengpid, S. (2019). Prevalence and associated factors of enacted, internalized and anticipated stigma among people living with HIV in South Africa: Results of the first national survey. HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care, 11, 275–285. https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S229285

- Reinius, M., Wettergren, L., Wiklander, M., Svedhem, V., Ekström, A. M., & Eriksson, L. E. (2017). Development of a 12-item short version of the HIV stigma scale. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12955-017-0691-Z

- Rodriguez-Hart, C., Nowak, R. G., Musci, R., German, D., Orazulike, I., Kayode, B., Hongjie, L. I., Gureje, O., Crowell, T. A., Baral, S., & Charurat, M. (2017). Pathways from sexual stigma to incident HIV and sexually transmitted infections among Nigerian MSM. Aids (london, England), 31(17), 2415–2420. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001637

- Scheim, A., Lyons, C., Ezouatchi, R., Liestman, B., Drame, F., Diouf, D., Ba, I., Bamba, A., Kouame, A., & Baral, S. (2019). Sexual behavior stigma and depression among transgender women and cisgender men who have sex with men in Côte d’Ivoire. Annals of Epidemiology, 33, 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.03.002

- Schrimshaw, E. W., Downing, M. J., & Cohn, D. J. (2018). Reasons for non-disclosure of sexual orientation among behaviorally bisexual men: Non-disclosure as stigma management. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(1), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0762-y

- Schwartz, S. R., Nowak, R. G., Orazulike, I., Keshinro, B., Ake, J., Kennedy, S.,Njoku, O., Blattner, W. A., Charurat, M. E., & Baral, S. D. (2015). The immediate effect of the same-Sex marriage prohibition act on stigma, discrimination, and engagement on HIV prevention and treatment services in men who have sex with men in Nigeria: Analysis of prospective data from the TRUST cohort. The Lancet HIV, 2(7), e299–e306. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-3018(15)00078-8

- Siegler, A. J., Wiatrek, S., Mouhanna, F., Amico, K. R., Dominguez, K., Jones, J., Patel, R. R., Mena, L. A., & Mayer, K. H. (2020). Validation of the HIV Pre-exposure prophylaxis stigma scale: Performance of Likert and semantic differential scale versions. AIDS and Behavior, 24(9), 2637–2649. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10461-020-02820-6

- Stannah, J., Dale, E., Elmes, J., Staunton, R., Beyrer, C., Mitchell, K. M., & Boily, M. C. (2019). HIV testing and engagement with the HIV treatment cascade among men who have sex with men in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet HIV, 6(11), e769–e787. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30239-5

- Sullivan, P. S., Carballo-Diéguez, A., Coates, T., Goodreau, S. M., McGowan, I., Sanders, E. J., Smith, A., Goswami, P., & Sanchez, J. (2012). Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. The Lancet. Lancet Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60955-6

- Sullivan, P. S., Mena, L., Elopre, L., & Siegler, A. J. (2019). Implementation strategies to increase PrEP uptake in the south. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 16(4), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11904-019-00447-4

- Taegtmeyer, M., Davies, A., Mwangome, M., van der Elst, E. M., Graham, S. M., Price, M. A., & Sanders, E. J. (2013). Challenges in providing counselling to MSM in highly stigmatized contexts: Results of a qualitative study from Kenya. PLoS ONE, 8(6), e64527. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064527

- Tobias, C. R., Cunningham, W., Cabral, H. D., Cunningham, C. O., Eldred, L., Naar-King, S., Bradford, J., Sohler, N. L., Wong, M. D., & Drainoni, M. L. (2007). Living with HIV but without medical care: Barriers to engagement. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 21(6), 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2006.0138

- Torres, T. S., Marins, L. M. S., Veloso, V. G., Grinsztejn, B., & Luz, P. M. (2019). How heterogeneous are MSM from Brazilian cities? An analysis of sexual behavior and perceived risk and a description of trends in awareness and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis. BMC Infectious Diseases, 19(1), 1067. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12879-019-4704-X

- Tucker, A., Liht, J., de Swardt, G., Jobson, G., Rebe, K., McIntyre, J., & Struthers, H. (2014). Homophobic stigma, depression, self-efficacy and unprotected anal intercourse for peri-urbantownship men who have sex with men in CapeTown, South Africa: A cross-sectional associationmodel. AIDS Care, 26(7), 882–889. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.859652

- Turan, J. M., Elafros, M. A., Logie, C. H., Banik, S., Turan, B., Crockett, K. B., Pescosolido, B., & Murray, S. M. (2019). Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Medicine, 17(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1246-9

- Verboom, B., Melendez-Torres, G., & Bonell, C. P. (2018). Combination methods for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men (MSM). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(4), https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010939.pub2

- Visser, M. J., Kershaw, T., Makin, J. D., & Forsyth, B. W. C. (2008). Development of parallel scales to measure HIV-related stigma. AIDS and Behavior, 12(5), 759–771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9363-7

- Wei, C., Cheung, D. H., Yan, H., Li, J., Shi, L.-E., & Raymond, H. F. (2016). The impact of homophobia and HIV stigma on HIV testing uptake among Chinese men who have sex with men. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 71(1), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0000000000000815

- Williams, R., Cook, R., Brumback, B., Cook, C., Ezenwa, M., Spencer, E., & Lucero, R. (2020). The relationship between individual characteristics and HIV-related stigma in adults living with HIV: Medical monitoring project, Florida, 2015–2016. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-020-08891-3/TABLES/4

- Zhang, T. P., Liu, C., Han, L., Tang, W., Mao, J., Wong, T., Zhang, Y., Tang, S., Yang, B., Wei, C., & Tucker, J. D. (2017). Community engagement in sexual health and uptake of HIV testing and syphilis testing among MSM in China: A cross-sectional online survey. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 20(1), 21372. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.20.01/21372

Appendix A:

SHP Sexual Identity Stigma Questions

*Variables written in gray indicate variables that were dropped after factor analysis.