ABSTRACT

Mental illness is prevalent among people living with HIV (PLHIV) and hinders engagement in HIV care. While financial incentives are effective at improving mental health and retention in care, the specific effect of such incentives on the mental health of PLHIV lacks quantifiable evidence. We evaluated the impact of a three-arm randomized controlled trial of a financial incentive program on the mental health of adult antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiates in Tanzania. Participants were randomized 1:1:1 into one of two cash incentive (combined; provided monthly conditional on clinic attendance) or the control arm. We measured the prevalence of emotional distress, depression, and anxiety via a difference-in-differences model which quantifies changes in the outcomes by arm over time. Baseline prevalence of emotional distress, depression, and anxiety among the 530 participants (346 intervention, 184 control) was 23.8%, 26.6%, and 19.8%, respectively. The prevalence of these outcomes decreased substantially over the study period; additional benefit of the cash incentives was not detected. In conclusion, poor mental health was common although the prevalence declined rapidly during the first six months on ART. The cash incentives did not increase these improvements, however they may have indirect benefit by motivating early linkage to and retention in care.

Clinical Trial Number: NCT03341556

Introduction

Mental illness remains a leading cause of disability, affecting an estimated 10% of people worldwide (Global Burden of Disease, Citation2018), and is especially prominent among people living with HIV (PLHIV). A systematic review on the mental health of PLHIV in Sub-Saharan Africa found that across the majority of studies, roughly 20% of PLHIV suffered from mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety (Breuer et al., Citation2011), with the prevalence of mental illness ranging from 19% to 32% among PLHIV globally (Breuer et al., Citation2011; Gill et al., Citation2020; Niu et al., Citation2016; Shadloo et al., Citation2018).

Mental illness may be a substantial barrier to long-term engagement with care and is associated with decreased retention in HIV-related care (Byrd et al., Citation2020; Rooks-Peck et al., Citation2018; Yehia, Stewart, et al., Citation2015) and diminished capacity to achieve and maintain viral suppression. Studies have shown other mental illnesses to be negatively associated with viral suppression (Jain et al., Citation2020; Meffert et al., Citation2019; Yehia, Stephens-Shield, et al., Citation2015), with one study conducted in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania demonstrating the odds of viral suppression among PLHIV suffering from depressive symptoms to be 40% less than those without depressive symptoms (Meffert et al., Citation2019). A review by Remien et al. suggests the intersecting vulnerabilities faced by people living with both HIV and comorbid mental illness drive disengagement from HIV care. This “intersecting vulnerabilities’ framework suggests that the individual and structural barriers that predispose an individual to HIV and mental illness, including stigma, poverty, food insecurity, and violence, also complicate an individual’s capacity to remain engaged in care (Remien et al., Citation2019).

Recent studies with adult ART initiates in Tanzania have demonstrated that short-term cash incentive programs have the capacity to both bolster retention in care (Fahey et al., Citation2020; McCoy et al., Citation2017) and viral suppression (Fahey et al., Citation2020). A recent meta-analysis of 22 randomized controlled trials of financial incentives in the context of HIV concluded that financial incentives were associated with improved HIV testing, ART adherence, and retention in care (Krishnamoorthy et al., Citation2021). In regards to mental health, while the relationship between mental health and poverty is bidirectional (Lund, Citation2012), cash transfers can theoretically interrupt the role financial stress plays in the daily lives of impoverished individuals (McGuire et al., Citation2022). A qualitative study conducted among ART initiates in Tanzania revealed that beneficiaries of a conditional food and cash incentive program frequently reported a sense of reduced burden of mental illness (Czaicki et al., Citation2017) via addressing competing needs, stress alleviation related to being able to meet basic needs, and increasing motivation to attend clinic appointments. Further, several cash incentive programs implemented in low-and-middle income countries have reported unintended secondary benefits in the form of reduced depression, increased hopefulness, and improved physical health (Angeles et al., Citation2019; Kilburn et al., Citation2016; Ohrnberger, Anselmi et al., Citation2020, Ohrnberger, Ficheram, et al., Citation2020b). This study aimed to understand whether cash incentives that have been demonstrated to improve engagement in HIV care also bolster the mental health of newly initiated in care PLHIV.

Methods

We use data from a three-arm randomized controlled trial that was conducted at four clinics in Shinyanga, Tanzania from 2018 to 2019 and demonstrated that short-term cash incentives are an effective tool to promote retention in care and viral suppression at six months (Fahey et al., Citation2020). Methods have been previously described elsewhere in detail (Fahey et al., Citation2020). Participants were adult ART initiates who met the following criteria: (1) living with HIV, (2) ≥18 years of age, (3) initiated ART within the 30 days prior to enrollment in our study, and (4) were seeking care at one of the four study clinics. Participants were individually randomized 1:1:1 to a larger monthly cash incentive arm (∼$10.00 monthly for up to 6 months), a smaller monthly cash incentive arm (∼$4.50 monthly for up to 6 months), or a standard of care arm. Given that the three-arm trial was not powered for mental health outcomes, participants randomized to either of the cash incentive arms were combined and operationalized as one treatment group. All study procedures were approved by the UC Berkeley Institutional Review Board and the Tanzanian National Institute for Medical Research.

Eligible participants who provided informed consent were administered a questionnaire on mental health and sociodemographic characteristics through in-person interviews in Kiswahili at both baseline (pre-randomization) and at six-months. All participants received the standard HIV clinical services in accordance with Tanzanian guidelines (National AIDS Control Programme, Citation2017), including monthly clinic visits for at least their first six months in care (National AIDS Control Programme. National guidelines for the management of HIV and AIDS (sixth edn). Dar es Salaam: United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly, and Children, Citation2017, Citationn.d.). Study participants were asked to check-in with a tablet-based mHealth system during clinic visits, at which time cash incentives for eligible participants in the intervention arms were automatically disbursed via mobile banking (e.g., M-PESA), or, if unable to receive mobile payments, via cash in hand. In total, intervention participants could earn a maximum of six cash incentives (one monthly) conditional on visit attendance, totaling ∼$60 for the larger and ∼$27 for the smaller cash arm, respectively.

The outcomes of interest were three domains of mental health as measured by the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 25: emotional distress, depression, and anxiety (Derogatis et al., Citation1974). This 25-item scale assesses overall emotional distress and can be disaggregated into two subscales for depression and anxiety. For each item, participants rated how severely individual symptoms of depression and anxiety impact them, on a scale of 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”). Consistent with standard scoring algorithms of the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 25, we calculated the means for the subscales and created dichotomous variables for each using a cutoff of 1.75 to define symptoms of emotional distress, depression, and/or anxiety (Derogatis et al., Citation1974). This cutoff has been used and validated across global contexts, including among PLHIV in Sub-Saharan Africa (Ashaba et al., Citation2018; Hinton et al., Citation1994; Kaaya et al., Citation2002; Mollica et al., Citation1987). As a sensitivity analysis, a secondary cut-off of 1.14 was used given previous research showing the lower threshold was more reliable in a study of pregnant women living with HIV (Kaaya et al., Citation2002).

Statistical analysis

Univariate and bivariate descriptive statistics were used to examine the baseline characteristics of the overall study sample and by treatment arm. We then implemented a difference-in-difference analysis using a linear probability model to assess whether there were changes in mental health from baseline to six months in the study groups in the intent-to-treat sample (McCoy, Citation2017). We adjusted for site of recruitment to account for potential unobserved differences between the four clinics. Linear probability models can be used for data with binary outcomes, however given the linear nature of the model, can allow for predicted probabilities that are not constrained by 0 and 1 (Battey et al., Citation2019; Gomila, Citation2020). The main parameter of interest was the difference-in-differences between the intervention and control arms over time, representing the additional percentage point change, if any, in the prevalence of emotional distress, depression, and anxiety after the six-month study period in the cash arm over the standard of care arm.

Additionally, given that exposure to the full six-month intervention, i.e., clinic attendance and subsequent receipt of the cash incentive, was heterogeneous given different patterns of retention in care, we conducted an instrumental variable analysis to assess differential effects of the intervention among people who received all possible incentives (n = 6; “maximally exposed”) compared to those who had one or more missed visits (and therefore had less intervention “exposure” by virtue of receiving fewer incentives). The instrumental variable analysis approximates the effect of the actual treatment experience which presents the source for intervention efficacy, yet does not suffer from the biases of classical “as-treated” or “per-protocol” analyses, primarily being the lack of preservation of random assignment (Greenland, Citation2000). We operationalized the randomized treatment arm as the instrument, and the instrumented variable was the number of cash incentives received, corresponding to the number of clinic visits attended (out of a maximum of six). The resulting target parameter, the difference-in-difference coefficient, can be interpreted as the effect of “treatment on the treated” (Sussman & Hayward, Citation2010). We confirmed the assumptions necessary for an instrumental variable analysis, specifically marginal exchangeability, relevance, and the exclusion restriction, before proceeding with a two-stage least-squared model (Davies et al., Citation2013). The instrument (treatment assignment) was highly associated with intervention exposure (F-Statistic: < 0.001); further, there were no reported instances of a control participant receiving the intervention (i.e., contamination). A secondary analysis using a less stringent cutoff for maximal exposure (four of six cash incentives or 66% of exposure received) was also conducted.

Overall, 10.6% of participants were missing outcome data. In order to reduce potential bias due to loss to follow-up, we used multiple imputation to estimate missing outcomes (Sterne et al., Citation2009). We present the following two models: the intent to treat analysis and the instrumental variable analysis, both using imputed outcome data. Results from the complete case analysis and the secondary instrumental variable analysis are presented as supplementary material. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 16 (Version 16, StataCorp LLC., College Station, TX).

Results

Descriptive analysis

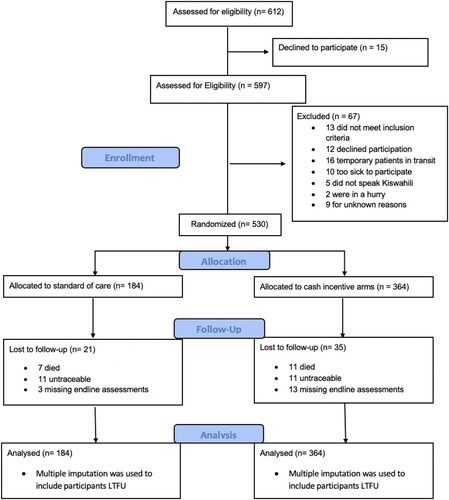

A total of 612 individuals were recruited of whom 597 were assessed for eligibility and 541 were eligible for study inclusion. A total of 530 participants (98% of eligible sample) were enrolled (184 standard of care, 346 to one of the two cash incentive arms; ).

Characteristics were balanced at baseline (). The majority of participants were female (62%), married or partnered (54%), were the head or joint head of household (76%), and had at least some formal schooling (79%). Cumulative attendance at HIV care visits over the study period was higher in the intervention arm (results not shown) and nearly half (46%) of individuals in the cash incentive groups were maximally exposed to the intervention (i.e., received six out of six possible cash transfers); 91% received at least four transfers.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of adult antiretroviral treatment initiates in Tanzania; 2018–2019.

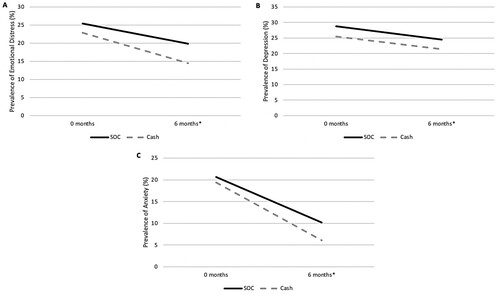

Mental health was balanced by arm at baseline; 23.8% of participants reported experiencing emotional distress, 26.6% experiencing depression, and 19.8% experiencing anxiety. The prevalence of participants experiencing emotional distress, depression, and anxiety at six months respectively decreased to 14.60%, 20.30%, and 5.50% in the imputed sample ().

Difference-in-Difference analysis

Emotional distress decreased by 5.7 percentage points over the six-month study period in the SOC arm (95% confidence interval [CI]: −14.3, 3.0; ; ), and 8.4 percentage points in the cash arm (95% CI: −14.4, −2.4). The difference-in-difference interaction term revealed an additional 2.7 percentage point, non-significant decline in emotional distress in the cash intervention arm (95% CI: −13.2, 7.7). Results using a complete case approach were similar (Supplementary Table 1). Receiving maximal intervention exposure (six out of six transfers) demonstrated an impact on emotional distress approximately two times greater than the magnitude of the intent-to-treat estimate (−6.6; 95% CI: −31.8, 18.6) although it was not statistically significant at the 5% threshold (). Results using a lower threshold for compliance were similar to those when using a higher threshold for maximal exposure (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2. Effects of time and cash incentive assignment on mental health outcomes, stratified by treatment arm; Shinyanga, Tanzania, 2018–2019.

Table 3. Estimates of the impact of maximum intervention exposure (receipt of 6/6 cash transfers) on mental health outcome using an instrumental variable approach and the imputed outcomes; Shinyanga, Tanzania, 2018–2019.

There was a 4.3 percentage point reduction in depression over the six-month study period in the standard of care arm (95% CI: −13.6, 4.9) and a 4.0 percentage point reduction in the cash arm (95% CI: −10.6, 2.6). The difference-in-difference term suggests a negligible additional change in prevalence of depression in the cash arm over the standard of care arm (−0.36; 95% CI: −11.1, 11.8). Results using a complete case approach were similar (supplementary Table 1). Receiving maximal intervention exposure also demonstrated a negligible difference-in-difference in the prevalence of depression in the cash arm over the standard of care arm (0.87; 95% CI: −26.7, 28.5).

There was a 10.4 percentage point reduction in the prevalence of anxiety over the six-month study period among the standard of care arm (95% CI: −17.8, −3.1) and a 13.3 percentage point reduction in the cash arm (95% CI: −18.2, −8.4.) The difference-in-difference interaction term suggests an additional, non-significant reduction among the cash arm, with the prevalence of anxiety lowering by an additional 2.9 percentage points over the SOC arm by the end of the study period (95% CI: −11.7, 6.0.) Results using a complete case approach were similar (supplementary Table 1). Receiving maximal intervention exposure was associated with statistically significant declines in anxiety among both arms over time, with the additional decline in the maximally exposed cash group approximately two times greater than the magnitude of the intent-to-treat estimate, although the difference-in-difference parameter was not statistically significant (−6.9; 95%).

Discussion

This study demonstrated a substantial reduction in the prevalence of emotional distress, depression, and anxiety in the first six months after ART initiation in Tanzania, with small to no additional effects of the cash incentive program on various mental health outcomes over time. Further, this study confirms the disproportionate burden of poor mental health among PLHIV in Tanzania. While estimates among the general population in Tanzania suggest a national prevalence of 3.6% (Dattani et al., Citation2018) for depression and anxiety independent of HIV status, roughly one-in-four study participants had symptoms consistent with depression and/or anxiety at ART initiation (baseline), highlighting the disproportionate burden of poor mental health among PLHIV and the need for action. The considerable reduction in poor mental health over time strongly suggests that time in HIV care may be a greater driver of mental health improvements among PLHIV than the potentially stress-alleviating effects of cash transfers, particularly as it pertains to symptoms of anxiety. Further, while this study detected small to no additional effects of the cash incentive program on mental health, retention in care was higher in the intervention arm (Fahey et al., Citation2020), and the cash incentives did not have any negative impacts on the participants’ mental health status.

This study was a secondary analysis of a recent randomized controlled trial that demonstrated the efficacy of conditional cash incentives as a tool to bolster engagement and promote viral suppression among ART initiates in Tanzania (Fahey et al., Citation2020). While the parent study revealed significant effects of the cash incentive program on viral suppression, potential secondary unintended benefits of this intervention, including those on the mental health, had not been previously investigated. Other studies (Dutra et al., Citation2019; McCoy et al., Citation2009) have found that the act of engaging with HIV care and treatment can give recently diagnosed and individuals newly initiated on ART a sense of control over their mental and physical health, regardless of cash incentives. Specifically, retention in the early stages of ART treatment to be associated with improved physical and mental health, as well as overall quality of life, as individuals acclimate to their diagnosis and experience the benefits of treatment (Dutra et al., Citation2019). These findings are consistent with the current study’s demonstration of a strong reduction in the prevalence of symptoms of mental illness in the standard of care arm over the six-month study period, which ranged from a 4.9 percentage point reduction in depression, to a statistically significant 11.0 percentage point reduction in anxiety. These prior studies contextualize and substantiate the improvements seen in this study, as individuals starting ART come to terms with their diagnosis and treatment plan during the early stages of their ART regimen.

While the parent study theorized and demonstrated that incentives would improve both retention in care and viral suppression, qualitative research from the pilot study revealed that improvements in mental health were an unexpected benefit of the intervention (Czaicki et al., Citation2017), justifying a more formal assessment of the intervention’s direct impact on mental health. Indeed, PLHIV often have to make tradeoffs between actions conducive to HIV treatment and care (e.g., attending clinic visits) and basic needs (Palar et al., Citation2018), and this balance can be tipped by small incentives which also alleviate stress and anxiety (Czaicki et al., Citation2017). At the same time, retention in care has a documented bidirectional relationship with mental health status among PLHIV (Byrd et al., Citation2020; Yehia, Stewart, et al., Citation2015). Thus it stands to reason that even though we did not detect statistically significant benefits of the cash incentives on mental health above and beyond the temporal reductions in poor mental health, our findings may have been mediated by retention in care. While the study was not powered to conduct this mediation analysis, the instrumental variable analysis presents another method for isolating and identifying the path (s) through which receipt of the cash incentives might affect mental health. Specifically, the instrumental variable approach permits analysis of the effect of “treatment on the treated”, which is of particular interest in settings where there is non-compliance in regards to the exposure (Ye et al., Citation2014). Although the study did not detect significant benefits (nor harms) associated with the cash incentives on mental health over time in the instrumental variable analysis, effect sizes were in the hypothesized, beneficial direction. The consistency in direction and increase in magnitude of effect compared to the primary intent to treat analysis further supports the hypothesis that the cash incentives do no harm and may in fact confer an additional, albeit small, benefit, especially for anxiety, in a study with more statistical power to detect small effect sizes. Further, examining a lower cutoff for intervention exposure in the secondary instrumental variable analysis yielded results consistent with the higher cutoff, indicating that if there was a benefit of the intervention on mental health, the same potential might be achieved with fewer cash incentives. This theory could be tested in future iterations of the intervention. Taken together, the instrumental variable analysis’ consistency with the primary results may strengthen the hypothesis that the cash incentives may improve mental health, and provides future programmatic insight on the quantity of incentives to achieve improvements in mental health.

This study is not without limitations. The parent study was powered on the primary aim of retention in care and viral suppression, not mental health. As such, our study was not powered to detect small effects of the cash incentive program on mental health above and beyond the dramatic reductions in symptoms of mental illness we observed over time across both treatment arms. This inherently impacts both the primary analysis reported in this paper as well as the secondary instrumental variable analysis. Future studies aiming to improve both engagement in care and mental health could be tailored specifically to PLHIV who meet criteria for at least one adverse mental health outcome to ensure sufficient power for a primary mental health outcome and to meet the unique needs of individuals dealing with these comorbidities throughout the course of their treatment. Further, the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 25 has not been validated specifically for adults living with HIV in Tanzania. One validation study suggested that the most appropriate Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 25 cutoff among pregnant woman living with HIV in Tanzania to be 1.14, as opposed to the traditional 1.75 (Kaaya et al., Citation2002). Supplemental analyses using this lower cutoff revealed an expected increase in the prevalence of mental illness and increased reduction over time (results not shown); however the impact of the financial incentives remained negligible. Given this finding, our estimates of mental health prevalence using the traditional cutoff are potentially conservative and may underestimate the burden of mental illness among newly diagnosed Tanzanian PLHIV. While limited by concerns on participant burden due to survey length, the use of multiple different measures of mental health could have aided in a more comprehensive assessment of mental health. At the same time, the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 25 assesses three distinct and important dimensions of mental health symptomology – emotional distress, depression, and anxiety – which allowed our study to assess potential intervention impacts on these unique yet related domains. Further, while study retention was high, 10.6% of study participants either passed away, were missing assessments, or were lost to follow up (). Relying on a complete case analysis of available data could introduce selection bias; the use of structured tracing procedures and multiple imputation are rigorous methods we employed to reduce this potential bias.

Despite these limitations, this study has a number of key strengths. First, targeting and intervening on PLHIV initiating ART as achieved in this study has the potential to set a trajectory for optimal HIV, mental, and physical health. We found substantial decreases in mental illnesses over the study period, which could be explained by the intensive, monthly visits as part of the standard of care for ART initiates in Tanzania. Second, the consistency of results between the complete case, imputed, and instrumental variable analysis lends credibility to the potential of the intervention to alleviate mental health disorders among initiates of ART.

In conclusion, this study is among the first to investigate the effect of cash incentive programs on mental health among PLHIV. Our findings confirm the disproportionate burden of mental illness among adults ART initiates in rural Tanzania, as well as highlight dramatic reductions in the prevalence of mental illness, particularly anxiety, during the first six months in care. The addition of small cash incentives did not substantially add to these improvements, however they may have indirect benefit by providing additional motivation for early linkage to and retention in ART services. While future studies should investigate these effects specifically among PLHIV diagnosed with a psychiatric comorbidity, this analysis suggests promise for the potential of joint improvements as it pertains to both viral suppression and mental health.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Angeles, G., de Hoop, J., Handa, S., Kilburn, K., Milazzo, A., & Peterman, A. (2019). Government of Malawi’s unconditional cash transfer improves youth mental health. Social Science & Medicine 1982, 225, 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.037

- Ashaba, S., Kakuhikire, B., Vořechovská, D., Perkins, J. M., Cooper-Vince, C. E., Maling, S., Bangsberg, D. R., & Tsai, A. C. (2018). Reliability, validity, and factor structure of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25: population-based study of persons living with HIV in rural Uganda. AIDS and Behavior, 22(5), 1467–1474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1843-1

- Battey, H. S., Cox, D. R., & Jackson, M. V. (2019). On the linear in probability model for binary data. Royal Society Open Science, 6(5), 190067. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.190067

- Breuer, E., Myer, L., Struthers, H., & Joska, J. A. (2011). HIV/AIDS and mental health research in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. African Journal of AIDS Research, 10(2), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2011.593373

- Byrd, K. K., Hardnett, F., Hou, J. G., Clay, P. G., Suzuki, S., Camp, N. M., Shankle, M. D., Weidle, P. J., & Taitel, M. S. (2020). Improvements in retention in care and HIV viral suppression among persons with HIV and comorbid mental health conditions: patient-centered HIV care model. AIDS and Behavior, 24(12), 3522–3532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02913-2

- Czaicki, N. L., Mnyippembe, A., Blodgett, M., Njau, P., & McCoy, S. I. (2017). It helps me live, sends my children to school, and feeds me: A qualitative study of how food and cash incentives may improve adherence to treatment and care among adults living with HIV in Tanzania. AIDS Care, 29(7), 876–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2017.1287340

- Dattani, S., Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2018). Mental health. Our world in data. Retrieved Oct, 7, 2019.

- Davies, N. M., Smith, G. D., Windmeijer, F., & Martin, R. M. (2013). Brief report: Issues in the reporting and conduct of instrumental variable studies: A systematic review. Epidemiology, 24(3), 363–369. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828abafb

- Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickels, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H., & Covi, L. (1974). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL). A measure of primary symptom dimensions. Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry, 7, 79–110. https://doi.org/10.1159/000395070

- Dutra, B. S., Lédo, A. P., Lins-Kusterer, L., Luz, E., Prieto, I. R., & Brites, C. (2019). Changes health-related quality of life in HIV-infected patients following initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a longitudinal study. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 23, 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2019.06.005

- Fahey, C. A., Njau, P. F., Katabaro, E., Mfaume, R. S., Ulenga, N., Mwenda, N., Bradshaw, P. T., Dow, W. H., Padian, N. S., Jewell, N. P., & McCoy, S. I. (2020). Financial incentives to promote retention in care and viral suppression in adults with HIV initiating antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania: a three-arm randomised controlled trial. The Lancet HIV, 7(11), e762–e771. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30230-7

- Gill, A., Ranasinghe, A., Sumathipala, A., & Fernando, K. A. (2020). Prevalence of mental health conditions amongst people living with human immunodeficiency virus in one of the most deprived localities in England. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 31(7), 619–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462420904299

- Global Burden of Disease. (2018). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.

- Gomila, R. (2020). Logistic or linear? Estimating causal effects of experimental treatments on binary outcomes using regression analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 150(4), 700–709. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000920

- Greenland, S. (2000). An introduction to instrumental variables for epidemiologists. International Journal of Epidemiology, 29(6), 1102. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.ije.a019909

- Hinton, W. L., Du, N., Chen, Y. C., Tran, C. G., Newman, T. B., & Lu, F. G. (1994). Screening for major depression in Vietnamese refugees: a validation and comparison of two instruments in a health screening population. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 9(4), 202–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02600124

- Jain, M. K., Li, X., Adams-Huet, B., Tiruneh, Y. M., Luque, A. E., Duarte, P., Trombello, J. M., & Nijhawan, A. E. (2020). The risk of depression among racially diverse people living with HIV: the impact of HIV viral suppression. AIDS Care, 33(5), 645–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1815167

- Kaaya, S. F., Fawzi, M. C. S., Mbwambo, J. K., Lee, B., Msamanga, G. I., & Fawzi, W. (2002). Validity of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 amongst HIV-positive pregnant women in Tanzania. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 106(1), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01205.x

- Kilburn, K., Thirumurthy, H., Halpern, C. T., Pettifor, A., & Handa, S. (2016). Effects of a large-scale unconditional cash transfer program on mental health outcomes of young people in Kenya. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(2), 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.023

- Krishnamoorthy, Y., Rehman, T., & Sakthivel, M. (2021). Effectiveness of financial incentives in achieving UNAID fast-track 90-90-90 and 95-95-95 target of HIV care continuum: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. AIDS and Behavior, 25(3), 814–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03038-2

- Lund, C. (2012). Poverty and mental health: a review of practice and policies. Neuropsychiatry, 2(3), 213–219. https://doi.org/10.2217/npy.12.24

- McCoy, C. E. (2017). Understanding the intention-to-treat principle in randomized controlled trials. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18(6), 1075–1078. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2017.8.35985

- McCoy, S. I., Miller, W. C., MacDonald, P. D. M., Hurt, C. B., Leone, P. A., Eron, J. J., & Strauss, R. P. (2009). Barriers and facilitators to HIV testing and linkage to primary care: narratives of people with advanced HIV in the Southeast. AIDS Care, 21(10), 1313–1320. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120902803174

- McCoy, S. I., Njau, P. F., Fahey, C., Kapologwe, N., Kadiyala, S., Jewell, N. P., Dow, W. H., & Padian, N. S. (2017). Cash vs. food assistance to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults in Tanzania. Aids (london, England), 31(6), 815–825. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001406

- McGuire, J., Kaiser, C., & Bach-Mortensen, A. M. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of cash transfers on subjective well-being and mental health in low-and middle-income countries. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(3), 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01252-z

- Meffert, S. M., Neylan, T. C., McCulloch, C. E., Maganga, L., Adamu, Y., Kiweewa, F., Maswai, J., Owuoth, J., Polyak, C. S., Ake, J. A., & Valcour, V. G. (2019). East African HIV care: depression and HIV outcomes. Global Mental Health, 6, e9. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2019.6

- Mollica, R. F., Wyshak, G., de Marneffe, D., Khuon, F., & Lavelle, J. (1987). Indochinese versions of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25: a screening instrument for the psychiatric care of refugees. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(4), 497–500. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.144.4.497

- National AIDS Control Programme. (2017). National Guidelines for the Management of HIV and AIDS (No. Sixth Edition). National AIDS Control Programme, Tanzania.

- National AIDS Control Programme. (n.d.). National guidelines for the management of HIV and AIDS (sixth edn). Dar es Salaam: United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly, and Children, 2017.

- Niu, L., Luo, D., Liu, Y., Silenzio, V. M. B., & Xiao, S. (2016). The mental health of people living with HIV in China, 1998-2014: A systematic review. PloS One, 11, e0153489. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153489

- Ohrnberger, J., Anselmi, L., Fichera, E., & Sutton, M. (2020). The effect of cash transfers on mental health: Opening the black box – A study from South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 260, 113181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113181

- Ohrnberger, J., Fichera, E., Sutton, M., & Anselmi, L. (2020). The effect of cash transfers on mental health - new evidence from South Africa. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 436. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08596-7

- Palar, K., Wong, M. D., & Cunningham, W. E. (2018). Competing subsistence needs are associated with retention in care and detectable viral load among people living with HIV. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services, 17(3), 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/15381501.2017.1407732

- Remien, R. H., Stirratt, M. J., Nguyen, N., Robbins, R. N., Pala, A. N., & Mellins, C. A. (2019). Mental health and HIV/AIDS: the need for an integrated response. Aids (london, England), 33(9), 1411–1420. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002227

- Rooks-Peck, C. R., Adegbite, A. H., Wichser, M. E., Ramshaw, R., Mullins, M. M., Higa, D., & Sipe, T. A. (2018). The prevention research synthesis project. Mental health and retention in HIV care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 37, 574–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000606

- Shadloo, B., Amin-Esmaeili, M., Motevalian, A., Mohraz, M., Sedaghat, A., Gouya, M. M., & Rahimi-Movaghar, A. (2018). Psychiatric disorders among people living with HIV/AIDS in IRAN: Prevalence, severity, service utilization and unmet mental health needs. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 110, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.04.012

- Sterne, J. A. C., White, I. R., Carlin, J. B., Spratt, M., Royston, P., Kenward, M. G., Wood, A. M., & Carpenter, J. R. (2009). Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ, 338(jun29 1), b2393–b2393. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2393

- Sussman, J. B., & Hayward, R. A. (2010). An IV for the RCT: using instrumental variables to adjust for treatment contamination in randomised controlled trials. BMJ, 340(may04 2), c2073–c2073. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c2073

- Ye, C., Beyene, J., Browne, G., & Thabane, L. (2014). Estimating treatment effects in randomised controlled trials with non-compliance: A simulation study. BMJ Open, 4, e005362. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005362

- Yehia, B. R., Stephens-Shield, A. J., Momplaisir, F., Taylor, L., Gross, R., Dubé, B., Glanz, K., & Brady, K. A. (2015). Health outcomes of HIV-infected people with mental illness. AIDS and Behavior, 19(8), 1491–1500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1080-4

- Yehia, B. R., Stewart, L., Momplaisir, F., Mody, A., Holtzman, C. W., Jacobs, L. M., Hines, J., Mounzer, K., Glanz, K., & Metlay, J. P. (2015). Barriers and facilitators to patient retention in HIV care. BMC Infectious Diseases, 15(1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-0990-0