ABSTRACT

Economic insecurity and poverty present major barriers to HIV care for young people. We conducted a systematic review of the current evidence for the effect of economic interventions on HIV care outcomes among pediatric populations encompassing young children, adolescents, and youth (ages 0–24). We conducted a search of PubMed MEDLINE, Cochrane, Embase, Scopus, CINAHL, and Global Health databases on October 12, 2022 using a search strategy curated by a medical librarian. Studies included economic interventions targeting participants <25 years in age which measured clinical HIV outcomes. Study characteristics, care outcomes, and quality were independently assessed, and findings were synthesized. Title/abstract screening was performed for 1934 unique records. Thirteen studies met inclusion criteria, reporting on nine distinct interventions. Economic interventions included incentives (n = 5), savings and lending programs (n = 3), and government cash transfers (n = 1). Study designs included three randomized controlled trials, an observational cohort study, a matched retrospective cohort study, and pilot intervention studies. While evidence is very limited, some promising findings were observed supporting retention and viral suppression, particularly for those with suboptimal care engagement or with detectable viral load. There is a need to further study and optimize economic interventions for children and adolescents living with HIV.

PROSPERO Number:

Introduction

An estimated 2.8 million children and adolescents (ages 0–19) and 3.3 million youth (ages 15–24) are living with HIV globally, the majority of whom live in Africa (United Nations Children's Fund, Citation2021). Engagement in HIV care presents particular challenges for young people and their families (Enane et al., Citation2020; Enane et al., Citation2018). Children and adolescents with HIV face multilevel barriers to retention in care and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), including HIV stigma, socioeconomic factors, family-level challenges, and unmet mental health needs (Enane et al., Citation2018; Enane et al., Citation2018; Hall et al., Citation2017).

Given that children, adolescents, and youth are particularly influenced by the social determinants of health and have lower retention and HIV viral suppression compared to older age groups, increased household economic stability and empowerment may support their HIV care engagement and health outcomes. In qualitative work, adolescents living with HIV describe needs for economic interventions to potentially address multiple barriers to sustained HIV care engagement (Enane et al., Citation2020; Vreeman et al., Citation2021). Predominant socioeconomic barriers to HIV care for children and adolescents include costs of transportation and healthcare needs, lost time from school or work, food and housing insecurity, caregiver illness or disability, competing financial needs, and additional challenges and stressors (Enane et al., Citation2020; Enane et al., Citation2018; Myers et al., Citation2021). HIV stigma can further limit a caregiver’s ability to raise funds to support a child’s care (Enane et al., Citation2021; Enane et al., Citation2020). Pragmatic strategies successfully targeting socioeconomic barriers to HIV care for children and adolescents and improving care outcomes are urgently needed (Ssewamala et al., Citation2020).

Economic interventions, which have shown promise for alleviating severe poverty and HIV risk, may have a role in addressing socioeconomic barriers to HIV care engagement for young people (Kennedy et al., Citation2014; Mavegam et al., Citation2017; Nadkarni et al., Citation2019; Owusu-Addo et al., Citation2018). An expanding body of evidence from adults indicates a correlation between economic interventions like cash transfers and improved HIV outcomes such as ART adherence, retention in care and viral suppression (Arrivillaga et al., Citation2014; Brantley et al., Citation2018; Czaicki et al., Citation2018; El-Sadr et al., Citation2017; Nadkarni et al., Citation2019; Weiser et al., Citation2015). However, there have been comparably fewer studies among children and adolescents living with HIV, despite the unique barriers to care faced by this population (Haberer & Mellins, Citation2009; Nadkarni et al., Citation2019). This systematic review aims to evaluate current evidence for the effectiveness of economic interventions on HIV care outcomes among children and youth.

Methods

Search strategy and terms

The protocol for this systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020200360). The systematic search was performed by a medical librarian using the following databases: PubMed MEDLINE, Cochrane, Embase, Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Global Health. Searches for all databases were performed on October 12, 2022. The search strategy was composed of four concepts, each comprised of terms related to: HIV; economic interventions or financial skills training; HIV treatment or care engagement outcomes (including those related to HIV viral load, CD4 count, adherence, or retention); and pediatric, adolescent, and youth populations. The search strategies for each database are reported in detail (Supplementary Material 1). To ensure that relevant studies were captured, reference lists of all included articles were reviewed to identify any additional studies for screening. We followed PRISMA guidelines for reporting on this systematic review (Page et al., Citation2021).

Definitions

This review studied economic interventions targeting pediatric or adolescent populations, defined as young child (0–9 years), adolescent (10–19 years), and youth (15–24 years) age groups. Economic interventions were defined as any transfer of cash or cash equivalents, loans/micro-loans, specialized financial or entrepreneurial training (such as farming, micro-enterprise, or micro-finance), or incentivized savings accounts. Government cash transfers were defined as government-provided cash support programs, which may take the form of conditional or unconditional cash transfers (Cluver et al., Citation2016). Financial incentives were defined as transfer of cash or cash equivalents dependent on a clinical outcome or behavior. Solely nutritional interventions such as food supplementation and transfer programs were excluded.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Included in this review were peer-reviewed studies of economic interventions involving transfer of financial resources (cash, loan/micro-loans, or skills) to a person living with HIV (PLHIV) or to their caregiver or household. Studies using a range of research designs were included if they reported quantitative HIV outcome measures, including HIV clinic visit attendance, loss to follow-up, adherence to ART, and/or HIV viral suppression.

Studies were excluded if: published prior to 1996; not available in English; not including PLHIV; not targeting a pediatric, adolescent, or youth population; not reporting any quantitative HIV outcomes; or focused exclusively on nutritional support or supplementation. Studies related to testing, linkage to care, and/or prevention alone without evaluation of HIV treatment outcomes were excluded, as were editorials, commentaries, conference abstracts, and reviews.

Screening

Title and abstract screening for relevance was conducted by two independent reviewers using the online platform Covidence (Veritas Health Information, Melbourne, Australia). Differing determinations between reviewers prompted in-depth review by the lead author to make a final determination. All relevant full-text articles were reviewed by two independent reviewers. Articles were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine final included studies.

Data extraction and analysis

Study characteristics and findings were abstracted from included studies, including study design, population, and setting; sample size; intervention characteristics; and reported quantitative HIV care outcomes and their definitions. Two reviewers independently extracted data which were subsequently independently checked for accuracy by both reviewers. Each study was reviewed in-depth, and findings were assessed and synthesized among the study team. Findings for outcomes of HIV viral suppression, retention in care, ART adherence, and CD4 count were synthesized with attention to study designs and quality; characteristics of study populations; characteristics of economic interventions studied; strength of evidence and magnitude of any intervention effects; and the state of evidence and current research gaps.

Quality assessment

The quality of the evidence and potential risk of bias was assessed using the Study Quality Assessment Tools developed by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), alongside study durations of observation and study attrition () (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Citation2023). The NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools were utilized due to the inclusion of heterogeneous study designs in this review, and the feasibility of using tailored tools according to study design. These tools have been utilized for previous systematic reviews, including in the field of adolescent health (Alsarrani et al., Citation2022; Musshafen et al., Citation2021; Schönfeld et al., Citation2021). The appropriate Study Quality Assessment Tool was selected and applied by two reviewers independently, and discrepancies in rating were resolved through discussion. Overall ratings and limitations to study quality were assessed.

Results

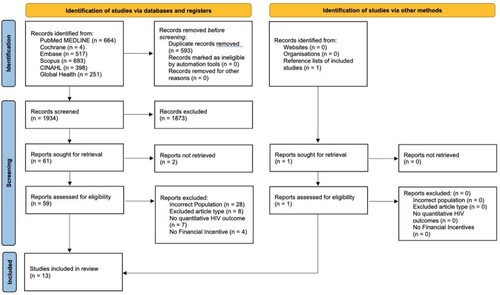

Our systematic search generated a total of 2,527 records (). Duplicates (n = 593) were removed. One additional article was identified from review of reference lists of included studies. In total, the full text was reviewed for 60 records. Thirteen studies met inclusion criteria, reporting on nine distinct interventions (). A cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating incentivized matched savings accounts was described by three manuscripts which are reviewed together (Bermudez et al., Citation2018; Brathwaite et al., Citation2022; Ssewamala et al., Citation2020). Similarly, a retrospective cohort study conducted in Rwanda and a cluster RCT conducted in Nigeria were each described by two manuscripts (Barnhart et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2018; Ekwunife et al., Citation2021; Nshimyumuremyi et al., Citation2022).

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

Table 2. Interventions and outcomes in included studies.

Table 3. Narrative summary of included economic interventions.

Quality assessment

Studies were evaluated for quality of evidence using the NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools, with each study evaluated using the appropriate tool (). Completed quality assessments are presented (Supplementary Material 2).

Table 4. Validity characteristics.

Only four randomized intervention studies are included in this review. Of these, one did not report the methods of the trial, and one studied HIV care outcomes as secondary outcomes only (MacCarthy et al., Citation2019; Mebrahtu et al., Citation2019). Of the two remaining RCTs, one faced limitations due to significant dissimilarities in baseline viral suppression between control and intervention populations, not meeting planned sample size, and ART regimen changes occurring unequally between groups during the intervention (Ekwunife et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2021). The remaining trial, the Suubi + Adherence intervention, provided the only randomized study focused primarily on HIV treatment outcomes that met intended sample size and did not face important validity challenges (Bermudez et al., Citation2018; Brathwaite et al., Citation2022; Ssewamala et al., Citation2020).

Two additional studies utilized observational or retrospective cohort designs with large sample sizes. An observational cohort study evaluating government cash transfers among other hypothesized development accelerators, faced no major limitations to internal validity, but conclusions from this study are limited by its observational nature (Cluver et al., Citation2019). A retrospective cohort study evaluating the implementation and outcomes of a programmatic intervention faced challenges in assessing its “real-world” implementation and effectiveness, including issues from inaccurate or missing data as well as changes and inconsistencies in the intervention approach (Barnhart et al., Citation2022; Nshimyumuremyi et al., Citation2022). Finally, among the included pilot studies, quality of evidence was limited by small sample sizes, relatively short observation periods, and lack of comparison groups (Foster et al., Citation2014; Galárraga et al., Citation2020; Wohl et al., Citation2011).

Populations and study settings

Of the included studies, only one examined HIV treatment outcomes in a young child age group, as secondary outcomes (Mebrahtu et al., Citation2019). The remaining studies either included adolescents only (Bermudez et al., Citation2018; Brathwaite et al., Citation2022; Cluver et al., Citation2019; Ekwunife et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2021; Galárraga et al., Citation2020; Ssewamala et al., Citation2020) or adolescents and youth (Barnhart et al., Citation2022; Foster et al., Citation2014; MacCarthy et al., Citation2019; Nshimyumuremyi et al., Citation2022; Wohl et al., Citation2011). Study settings were diverse in terms of geography, healthcare models and resources. Seven studied interventions were conducted in African countries; and one each was in the United States and in the United Kingdom (). Four reported on single-center studies (Foster et al., Citation2014; Galárraga et al., Citation2020; MacCarthy et al., Citation2019; Wohl et al., Citation2011). Others involved multiple clinical sites across a region (Barnhart et al., Citation2022; Bermudez et al., Citation2018; Brathwaite et al., Citation2022; Cluver et al., Citation2019; Ekwunife et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2021; Mebrahtu et al., Citation2019; Nshimyumuremyi et al., Citation2022; Ssewamala et al., Citation2020). Multiple studies specifically examined populations (or sub-populations) with intermittent adherence or engagement, viral non-suppression, and/or advanced immunosuppression (Foster et al., Citation2014; Ssewamala et al., Citation2020; Wohl et al., Citation2011).

Interventions

Studied economic interventions broadly included: a government cash transfer program (Cluver et al., Citation2019); financial incentives (Barnhart et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2021; Foster et al., Citation2014; Galárraga et al., Citation2020; MacCarthy et al., Citation2019; Nshimyumuremyi et al., Citation2022; Wohl et al., Citation2011); and internal savings and lending programs (Bermudez et al., Citation2018; Brathwaite et al., Citation2022; Mebrahtu et al., Citation2019; Ssewamala et al., Citation2020). The effect of receiving government cash transfers was evaluated in a single study, an observational cohort in South Africa, alongside other hypothesized development accelerators for improving adolescent outcomes (Cluver et al., Citation2019). Multiple studies evaluated financial incentives conditioned on individual health behaviors (Ekwunife et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2021; Foster et al., Citation2014; Wohl et al., Citation2011), group performance measures, (Barnhart et al., Citation2022; Galárraga et al., Citation2020; Nshimyumuremyi et al., Citation2022), and an incentive for entry in a drawing for mobile airtime (MacCarthy et al., Citation2019). Financial incentives were evaluated in two RCTs, a retrospective cohort study, and multiple pilot studies evaluating feasibility (). Finally, studies of internal savings plans established savings accounts either for individual families or for groups of study participants. Two of these plans offered additional financial incentives in addition to the savings account; one by matching savings contributions and one through cash incentives for health behaviors (Mebrahtu et al., Citation2019; Ssewamala et al., Citation2020).

Feasibility and targets

Challenges to intervention feasibility reported by included studies were broad, and included caregiver factors, stigma, laboratory challenges, acceptability of the intervention, and implementation challenges (Barnhart et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2021; Nshimyumuremyi et al., Citation2022). In Uganda, following a trial of randomized prize drawing, focus group participants noted significant demotivation when meeting behavior targets but drawing zero incentive (MacCarthy et al., Citation2019). Among three studies which included group incentives or group savings accounts, two noted challenges with group engagement (Mebrahtu et al., Citation2019; Nshimyumuremyi et al., Citation2022) while one reported overall high acceptability (Galárraga et al., Citation2020). Timing of receipt of the financial intervention is not explicitly reported for many studies; others specifically reported either cumulative payouts or delivery at clinic visits (Barnhart et al., Citation2022; Galárraga et al., Citation2020; Nshimyumuremyi et al., Citation2022; Wohl et al., Citation2011). Likewise, efforts to engage caregivers are not explicitly reported in most studies. Exceptions include explicitly stated designs of the RCTs conducted in Uganda and Zimbabwe (Brathwaite et al., Citation2022; Mebrahtu et al., Citation2019); and the inclusion of parenting support alongside cash transfers and safe schools in models of development accelerators in the observational cohort (Cluver et al., Citation2019). Notably in the RCT conducted in Uganda the matched savings account was structured to be used for care needs of the adolescent such as education and healthcare expenses (Brathwaite et al., Citation2022).

Outcomes

Studied economic interventions evaluated four domains of HIV outcomes: HIV viral suppression, retention/engagement, CD4 count, and adherence (). Findings related to each type of outcome are presented in order of highest quality of evidence.

Six studies evaluated the effect of economic interventions on viral suppression. Given the sample size, trial design, and quality of implementation, the strongest evidence related to viral suppression is provided by the matched savings program conducted in Uganda (Ssewamala et al., Citation2020). While this study did not find significant differences in viral suppression between intervention and control groups, it did observe an effect in the subset of adolescents with detectable viral load at baseline, with the intervention resulting in 1.5 times greater viral suppression in this group at 48 months (Ssewamala et al., Citation2020). Another RCT, conducted in Nigeria, did not find an effect on viral suppression with cash incentives; but was limited by significant group differences in baseline viral suppression (higher in the control group at baseline) and by the roll-out of dolutegravir-based regimens during the study (Ekwunife et al., Citation2022). A retrospective study of a programmatic intervention in Rwanda similarly did not identify an effect on viral suppression; however, implementation challenges and inaccurate or missing data undermined study validity (Barnhart et al., Citation2022; Nshimyumuremyi et al., Citation2022). The remaining interventions either examined viral suppression as a secondary outcome (in a small number of children with confirmed HIV infection) or were small pilot interventions, which provided preliminary evidence only.

Five studies evaluated engagement or retention in care. The previously described RCT in Nigeria and retrospective cohort study in Rwanda found no improvement in retention or engagement but have validity limitations noted above (Barnhart et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2022). By contrast, a large observational cohort in South Africa found that receipt of government transfers was associated with an increase in HIV care retention by 13% (95% CI 3–23%); combining cash transfers with parenting support and safe schools was associated with an increase in HIV care retention by 22% (95% CI 9–34%) (Cluver et al., Citation2019). Of the remaining pre–post intervention studies, one conducted in California did find improvement in retention specifically in a sub-analysis of patients who had attended less than two visits in the previous six months of care (Wohl et al., Citation2011).

Five studies evaluated ART adherence, including three RCTs, the observational cohort study, and a pilot study (Brathwaite et al., Citation2022; Cluver et al., Citation2019; Ekwunife et al., Citation2022; Galárraga et al., Citation2020; MacCarthy et al., Citation2019). Most of these measured self-reported adherence, while the RCT in Nigeria used a pill count measure (). Only the small pilot intervention noted a statistically significant improvement specifically in the change in missing ART doses from baseline to 9 months into the intervention (coefficient −0.19, 95% CI −0.38 to −0.03) (Galárraga et al., Citation2020).

Three studies evaluated CD4 count, all which were studies of financial incentives (Ekwunife et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2021; Foster et al., Citation2014; Galárraga et al., Citation2020). The RCT conducted in Nigeria did not observe effects on CD4 count; two pilot studies assessed CD4 count but were limited by very small sample sizes (Foster et al., Citation2014; Galárraga et al., Citation2020).

Discussion

This review identified studies evaluating a range of economic interventions dedicated to children, adolescents, or youth living with HIV. We found that there is very limited high-quality evidence evaluating the effect of economic interventions on pediatric HIV outcomes, which is limited to the adolescent and youth age group, and that this is an area where further high-quality studies are needed. Nevertheless, there are insights that emerge from the included studies which may inform further research and programs. Some promising findings were observed for effects on retention – with the greatest effect found in an observational study in South Africa evaluating receipt of government cash transfers (Cluver et al., Citation2019). Further, positive effects on retention and viral suppression were noted among adolescents with suboptimal care engagement or with detectable viral load, respectively. We discuss considerations related to target population, economic intervention characteristics, and HIV care outcome of interest, which may underlie differences in potential effects of economic interventions for young people with HIV.

Studies among adults living with HIV have observed benefits of economic interventions on viral suppression, adherence, and engagement in care, including studies performed in African countries and in the United States (Arrivillaga et al., Citation2014; Brantley et al., Citation2018; Czaicki et al., Citation2018; El-Sadr et al., Citation2017; Farber et al., Citation2013; Weiser et al., Citation2015). A large study of financial incentives conducted in Louisiana among individuals ages 13 through adulthood – not included in this review as it was not dedicated to a pediatric age group – observed the greatest increase in viral suppression among participants aged 13–29 – the group which also had lowest viral suppression at baseline (Brantley et al., Citation2018).

Evidence is much more limited in pediatric/adolescent populations. Most included studies were conducted in African countries, reflecting both the prevalence of pediatric HIV and what can be profound economic barriers to HIV care in these settings. Of the six included RCTs and large cohort studies, only two reached the highest quality of evidence: the incentivized matched savings intervention of Suubi + Adherence, and the analysis of government cash transfers in the observational cohort (Cluver et al., Citation2019; Ssewamala et al., Citation2020). Further, only the CHIDO trial included data for infants and young children with HIV, with limited numbers precluding meaningful assessment (Mebrahtu et al., Citation2019). Given the poor outcomes in pediatric HIV care for young children and the remarkable evidence gap, there is an urgent need for further research on economic interventions for infants and children with HIV and their families.

Beyond the relative paucity of high-quality evidence, multiple factors may contribute to the proportion of negative findings in this review. Concurrent interventions and observer effect may have clouded possible improvements in outcomes; as noted by the Suubi + Adherence team, both intervention and control groups in this RCT received “boosted” standard of care and had improvements in viral suppression over the course of the study. Additionally, timing and type of interventions may not meet family needs to address barriers to care. While most included studies did not clearly define when the financial incentive is distributed, delayed or inadequate incentives could fail to meet immediate barriers to retention, such as transportation costs, as noted by the investigator team in Rwanda (Nshimyumuremyi et al., Citation2022). Finally, while statistically significant differences in direct HIV outcomes may not be observed, it is important to recognize other important effects of economic interventions, and assess how economic stability might influence other positive health behaviors or outcomes (Brathwaite et al., Citation2022; Cluver et al., Citation2019).

This review found some positive effects of economic interventions on retention in HIV care. We consider the possibility that engagement or retention in HIV care may have greater potential for mitigation by economic interventions than other care outcomes. Important barriers to retention, including economic and food insecurity, transportation costs, inability for caregivers to take leave from work, or competing priorities, may be directly mitigated through financial support (Enane et al., Citation2020). By contrast, ART adherence may be a comparatively more complex health behavior, and while economic and food insecurity are important barriers, it is possible that there is a less direct effect of economic support on daily medication-taking.

It is notable, however, that effects on retention and adherence were observed in studies evaluating these in particularly vulnerable sub-cohorts of adolescents or youth with HIV. An RCT and a pilot intervention identified a significant improvement in outcomes for high-risk populations that were not present in the wider cohort analysis (Ssewamala et al., Citation2020; Wohl et al., Citation2011). Studies of adults have similarly found that economic incentives may have the greatest impact on groups at risk of care disengagement (El-Sadr et al., Citation2017). Young people with gaps in care or detectable viral load may have the most to gain from economic interventions, including by targeting unmet financial needs that contribute to care challenges. Further work is needed to elucidate mechanisms for economic interventions impacting pediatric HIV care outcomes, and to consider the design of interventions to potentially target or prioritize highly vulnerable young people.

Further consideration should also be given to the design of economic interventions, and to their combination with other holistic care supports. Caregiver and family resources to support pediatric/adolescent HIV care are important yet under-studied; effective interventions are needed to support caregiver needs and strengthen family supports for care (Myers et al., Citation2021). In this review, high-quality interventions with positive outcomes involved components of caregiver engagement: through an incentivized matched savings account and through modeled combined effects of cash transfer, parenting support, and safe schools (Bermudez et al., Citation2018; Cluver et al., Citation2019; Ssewamala et al., Citation2020). Caregiver engagement is further highlighted in a feasibility analysis informing the RCT in Nigeria, in which healthcare personnel noted the significant role of caregivers in relationships, transportation, and navigating stigma (Ekwunife et al., Citation2022; Ekwunife et al., Citation2021).

Other characteristics of economic interventions are likely to be important to their effectiveness, though conclusions cannot be drawn from the limited evidence. Potentially greater economic support may be provided by government cash transfers as opposed to clinic-based incentive programs. While most interventions in this review utilized some form of behavior-based financial transfer, both the Suubi + Adherence RCT in Uganda and the observational cohort study in South Africa examined economic interventions not conditioned on health outcomes, with positive results (Cluver et al., Citation2019; Ssewamala et al., Citation2020). Cash transfer programs are increasingly implemented, including in several African countries (Owusu-Addo et al., Citation2018) and studied outcomes have included those related to infectious diseases, particularly tuberculosis (Boccia et al., Citation2011) and HIV (Mills et al., Citation2018). Such interventions have potentially significant impact for many child and adolescent health outcomes, including those not specifically measured in this review.

Group savings and lending programs have also been utilized in African settings, though their impact on child health and outcomes is unclear (Orr, Citation2019). In Kenya, community health volunteer-led group-based health lessons during pregnancy paired with optional saving groups were associated with lower rates of at-risk development in infants (McHenry et al., Citation2021). A study in Zambia of women who had given birth in the past year found no correlation of group savings on healthcare utilization (Lee et al., Citation2022). The studies included in this review note mixed acceptability of group interventions and unclear effect on HIV outcomes. This may possibly relate in part to the effects of HIV stigma, decreased participant engagement when sharing a group benefit, and delayed access to funds among group members.

This review has several limitations. Study interventions and designs were highly heterogeneous, and both RCTs and pilot interventions encountered implementation challenges. This heterogeneity resulted in difficulty comparing study findings and quality. Economic interventions were typically packaged with psychosocial or case management support, limiting conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the economic component. Few studies were designed to establish a causal relationship between economic interventions and HIV care outcomes. This review did not examine evidence for prevention (of perinatal or sexual transmission of HIV), or for other child health or development outcomes, which are outside its scope. This review also did not evaluate interventions solely providing nutritional supplementation. By limiting articles to those available in English and excluding conference abstracts, relevant studies may have been excluded. Finally, by focusing on the economic intervention components and HIV care outcomes within the identified studies, this review may fail to fully highlight other important findings related to other study objectives or outcomes.

Conclusions

While evidence for the effect of economic interventions on pediatric HIV outcomes is very limited, some quality evidence exists for the potential impact of economic interventions for improving pediatric HIV outcomes, particularly for adolescents with gaps in care engagement or with detectable viral load. There is a need for high-quality studies to optimize economic interventions for pediatric and adolescent populations with HIV, to further evaluate their effectiveness, and to elucidate mechanisms and priority groups for these interventions. Given the critical need to improve HIV care outcomes of children, adolescents, and youth globally, economic interventions to address difficult socioeconomic barriers to care should be urgently investigated and implemented.

Author contributions

CBB and LAE designed the systematic review in conjunction with EF, who created the search strategy and identified appropriate databases. Title and abstract screening was conducted by CBB and MJA. CBB and JJT conducted the full text review, with supervisory contributions by LAE. CBB, JJT, and LAE reviewed all included studies and conducted data abstraction and synthesis of the evidence. CBB and LAE conducted the quality assessment. CBB drafted the initial manuscript. LAE and MSM provided significant revisions to the manuscript in structure and content. All authors participated in the revision of the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Morris Green Physician Scientist Development Program, and the Pediatrics Department of the Indiana University School of Medicine, for supporting resident-directed research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alsarrani, A., Hunter, R. F., Dunne, L., & Garcia, L. (2022). Association between friendship quality and subjective wellbeing among adolescents: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 2420. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14776-4

- Arrivillaga, M., Salcedo, J. P., & Pérez, M. (2014). The IMEA project: an intervention based on microfinance, entrepreneurship, and adherence to treatment for women with HIV/AIDS living in poverty. AIDS Education and Prevention, 26(5), 398–410. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2014.26.5.398

- Barnhart, D. A., Uwamariya, J., Nshimyumuremyi, J. N., Mukesharurema, G., Anderson, T., Ndahimana, J. d. A., Cubaka, V. K., & Hedt-Gauthier, B. (2022). Receipt of a combined economic and peer support intervention and clinical outcomes among HIV-positive youth in rural Rwanda: A retrospective cohort. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(6), e0000492. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000492

- Bermudez, L. G., Ssewamala, F. M., Neilands, T. B., Lu, L., Jennings, L., Nakigozi, G., Mellins, C. A., McKay, M., & Mukasa, M. (2018). Does economic strengthening improve viral suppression among adolescents living with HIV? Results from a cluster randomized trial in Uganda. AIDS and Behavior, 22(11), 3763–3772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2173-7

- Boccia, D., Hargreaves, J., Lönnroth, K., Jaramillo, E., Weiss, J., Uplekar, M., Porter, J. D. H., & Evans, C. A. (2011). Cash transfer and microfinance interventions for tuberculosis control: Review of the impact evidence and policy implications. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 15(Suppl 2), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.10.0438

- Brantley, A. D., Burgess, S., Bickham, J., Wendell, D., & Gruber, D. (2018). Using financial incentives to improve rates of viral suppression and engagement in care of patients receiving HIV care at 3 health clinics in Louisiana: The health models program, 2013-2016. Public Health Reports, 133(2_suppl), 75S–86S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354918793096

- Brathwaite, R., Ssewamala, F. M., Mutumba, M., Neilands, T. B., Byansi, W., Namuwonge, F., Damulira, C., Nabunya, P., Nakigozi, G., Makumbi, F., Mellins, C. A., McKay, M. M., & Team, S. A. F. (2022). The long-term (5-year) impact of a family economic empowerment intervention on adolescents living with HIV in Uganda: Analysis of longitudinal data from a cluster randomized controlled trial from the suubi+adherence study (2012–2018). AIDS and Behavior, 26(10), 3337–3344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03637-1

- Cluver, L. D., Orkin, F. M., Campeau, L., Toska, E., Webb, D., Carlqvist, A., & Sherr, L. (2019). Improving lives by accelerating progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals for adolescents living with HIV: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 3(4), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30033-1

- Cluver, L. D., Orkin, F. M., Meinck, F., Boyes, M. E., Yakubovich, A. R., & Sherr, L. (2016). Can social protection improve sustainable development goals for adolescent health? PLoS One, 11(10), e0164808. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164808

- Czaicki, N. L., Dow, W. H., Njau, P. F., & McCoy, S. I. (2018). Do incentives undermine intrinsic motivation? Increases in intrinsic motivation within an incentive-based intervention for people living with HIV in Tanzania. PLoS One, 13(6), e0196616. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196616

- Ekwunife, O. I., Anetoh, M. U., Kalu, S. O., Ele, P. U., Egbewale, B. E., & Eleje, G. U. (2022). Impact of conditional economic incentives and motivational interviewing on health outcomes of adolescents living with HIV in Anambra State, Nigeria: A cluster-randomised trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 30, 100997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2022.100997

- Ekwunife, O. I., Anetoh, M. U., Kalu, S. O., Ele, P. U., & Eleje, G. U. (2018). Conditional economic incentives and motivational interviewing to improve adolescents’ retention in HIV care and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Southeast Nigeria: study protocol for a cluster randomised trial. Trials, 19(1), 710. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-3095-4

- Ekwunife, O. I., Ofomata, C. J., Okafor, C. E., Anetoh, M. U., Kalu, S. O., Ele, P. U., & Eleje, G. U. (2021). Cost-effectiveness and feasibility of conditional economic incentives and motivational interviewing to improve HIV health outcomes of adolescents living with HIV in Anambra State, Nigeria. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 685. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06718-4

- El-Sadr, W. M., Donnell, D., Beauchamp, G., Hall, H. I., Torian, L. V., Zingman, B., Lum, G., Kharfen, M., Elion, R., Leider, J., Gordin, F. M., Elharrar, V., Burns, D., Zerbe, A., Gamble, T., & Branson, B. (2017). Financial incentives for linkage to care and viral suppression Among HIV-positive patients. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(8), 1083–1092. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2158

- Enane, L. A., Apondi, E., Omollo, M., Toromo, J. J., Bakari, S., Aluoch, J., Morris, C., Kantor, R., Braitstein, P., Fortenberry, J. D., Nyandiko, W. M., Wools-Kaloustian, K., Elul, B., & Vreeman, R. C. (2021). “I just keep quiet about it and act as if everything is alright” – The cascade from trauma to disengagement among adolescents living with HIV in western Kenya. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 24(4), e25695. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25695

- Enane, L. A., Apondi, E., Toromo, J., Bosma, C., Ngeresa, A., Nyandiko, W., & Vreeman, R. C. (2020). “A problem shared is half solved” – a qualitative assessment of barriers and facilitators to adolescent retention in HIV care in western Kenya. AIDS Care, 32(1), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2019.1668530

- Enane, L. A., Davies, M. A., Leroy, V., Edmonds, A., Apondi, E., Adedimeji, A., & Vreeman, R. C. (2018). Traversing the cascade: Urgent research priorities for implementing the ‘treat all’ strategy for children and adolescents living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Virus Eradication, 4(Suppl 2), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30344-7

- Enane, L. A., Vreeman, R. C., & Foster, C. (2018). Retention and adherence: Global challenges for the long-term care of adolescents and young adults living with HIV. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, 13(3), 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1097/COH.0000000000000459

- Farber, S., Tate, J., Frank, C., Ardito, D., Kozal, M., Justice, A. C., & Scott Braithwaite, R. (2013). A study of financial incentives to reduce plasma HIV RNA among patients in care. AIDS and Behavior, 17(7), 2293–2300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0416-1

- Foster, C., McDonald, S., Frize, G., Ayers, S., & Fidler, S. (2014). “Payment by results”—financial incentives and motivational interviewing, adherence interventions in young adults with perinatally acquired HIV-1 infection: A pilot program. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 28(1), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2013.0262

- Galárraga, O., Enimil, A., Bosomtwe, D., Cao, W., & Barker, D. H. (2020). Group-based economic incentives to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among youth living with HIV: Safety and preliminary efficacy from a pilot trial. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 15(3), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2019.1709678

- Haberer, J., & Mellins, C. (2009). Pediatric adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 6(4), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-009-0026-8

- Hall, B. J., Sou, K. L., Beanland, R., Lacky, M., Tso, L. S., Ma, Q., Doherty, M., & Tucker, J. D. (2017). Barriers and facilitators to interventions improving retention in HIV care: A qualitative evidence meta-synthesis. AIDS and Behavior, 21(6), 1755–1767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1537-0

- Kennedy, C. E., Fonner, V. A., O'Reilly, K. R., & Sweat, M. D. (2014). A systematic review of income generation interventions, including microfinance and vocational skills training, for HIV prevention. AIDS Care, 26(6), 659–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.845287

- Lee, H. E., Veliz, P. T., Maffioli, E. M., Munro-Kramer, M. L., Sakala, I., Chiboola, N. M., Ngoma, T., Kaiser, J. L., Rockers, P. C., Scott, N. A., & Lori, J. R. (2022). The role of Savings and Internal Lending Communities (SILCs) in improving community-level household wealth, financial preparedness for birth, and utilization of reproductive health services in rural Zambia: A secondary analysis. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1724. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14121-9

- MacCarthy, S., Mendoza-Graf, A., Huang, H., Mukasa, B., & Linnemayr, S. (2019). Supporting Adolescents to Adhere (SATA): Lessons learned from an intervention to achieve medication adherence targets among youth living with HIV in Uganda. Children and Youth Services Review, 102, 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.04.007

- Mavegam, B. O., Pharr, J. R., Cruz, P., & Ezeanolue, E. E. (2017). Effective interventions to improve young adults’ linkage to HIV care in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. AIDS Care, 29(10), 1198–1204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2017.1306637

- McHenry, M. S., Maldonado, L. Y., Yang, Z., Anusu, G., Kaluhi, E., Christoffersen-Deb, A., Songok, J. J., & Ruhl, L. J. (2021). Participation in a community-based women's health education program and at-risk child development in rural Kenya: Developmental screening questionnaire results analysis. Global Health: Science and Practice, 9(4), 818–831. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00349

- Mebrahtu, H., Simms, V., Mupambireyi, Z., Rehman, A. M., Chingono, R., Matsikire, E., Malaba, R., Weiss, H. A., Ndlovu, P., Cowan, F. M., & Sherr, L. (2019). Effects of parenting classes and economic strengthening for caregivers on the cognition of HIV-exposed infants: A pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial in rural Zimbabwe. BMJ Global Health, 4(5), e001651. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001651

- Mills, E. J., Adhvaryu, A., Jakiela, P., Birungi, J., Okoboi, S., Chimulwa, T. N. W., Wanganisi, J., Achilla, T., Popoff, E., Golchi, S., & Karlan, D. (2018). Unconditional cash transfers for clinical and economic outcomes among HIV-affected Ugandan households. Aids (london, England), 32(14), 2023–2031. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001899

- Musshafen, L. A., Tyrone, R. S., Abdelaziz, A., Sims-Gomillia, C. E., Pongetti, L. S., Teng, F., Fletcher, L. M., & Reneker, J. C. (2021). Associations between sleep and academic performance in US adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine, 83, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.04.015

- Myers, C., Apondi, E., Toromo, J. J., Omollo, M., Bakari, S., Aluoch, J., Morris, Z., Kantor, R., Braitstein, P., Nyandiko, W. M., Wools-Kaloustian, K., Elul, B., Vreeman, R. C., & Enane, L. A. (2021, July 18-21). “Who am I going to stay with? Who will accept me?” - A qualitative study of family-level factors underlying disengagement from HIV care among Kenyan adolescents. 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2021), Berlin/Virtual.

- Nadkarni, S., Genberg, B., & Galárraga, O. (2019). Microfinance interventions and HIV treatment outcomes: A synthesizing conceptual framework and systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 23(9), 2238–2252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02443-6

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. (2023). Study quality assessment tools. NIH. Retrieved 6/5/2023 from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools.

- Nshimyumuremyi, J. N., Mukesharurema, G., Uwamariya, J., Mutunge, E., Goodman, A. S., Ndahimana, J. D., & Barnhart, D. A. (2022). Implementation and adaptation of a combined economic empowerment and peer support program among youth living with HIV in rural Rwanda. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC), 21, 232595822110640. https://doi.org/10.1177/23259582211064038

- Okonji, E. F., Mukumbang, F. C., Orth, Z., Vickerman-Delport, S. A., & Van Wyk, B. (2020). Psychosocial support interventions for improved adherence and retention in ART care for young people living with HIV (10-24 years): A scoping review. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1841. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09717-y

- Orr, T. B. M., Carmichael, J., Lasway, C., & Chen, M. (2019). Savings groups plus: A review of the evidence. United States Agency for International Development. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00W5V7.pdf.

- Owusu-Addo, E., Renzaho, A. M. N., & Smith, B. J. (2018). Evaluation of cash transfer programs in sub-Saharan Africa: A methodological review. Evaluation and Program Planning, 68, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2018.02.010

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

- Schönfeld, M. S., Pfisterer-Heise, S., & Bergelt, C. (2021). Self-reported health literacy and medication adherence in older adults: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 11(12), e056307. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056307

- Ssewamala, F. M., Dvalishvili, D., Mellins, C. A., Geng, E. H., Makumbi, F., Neilands, T. B., McKay, M., Damulira, C., Nabunya, P., Sensoy Bahar, O., Nakigozi, G., Kigozi, G., Byansi, W., Mukasa, M., & Namuwonge, F. (2020). The long-term effects of a family based economic empowerment intervention (Suubi+Adherence) on suppression of HIV viral loads among adolescents living with HIV in southern Uganda: Findings from 5-year cluster randomized trial. PLoS One, 15(2), e0228370. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228370

- Troller-Renfree, S. V., Costanzo, M. A., Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K., Gennetian, L. A., Yoshikawa, H., Halpern-Meekin, S., Fox, N. A., & Noble, K. G. (2022). The impact of a poverty reduction intervention on infant brain activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(5), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2115649119

- United Nations Children's Fund. (2021). HIV Statistics - Global and regional trends. United Nations Children's Fund. https://data.unicef.org/topic/hivaids/global-regional-trends/.

- Vreeman, R. C., Rakhmanina, N. Y., Nyandiko, W. M., Puthanakit, T., & Kantor, R. (2021). Are we there yet? 40 years of successes and challenges for children and adolescents living with HIV. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 24(6), e25759. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25759

- Weiser, S. D., Bukusi, E. A., Steinfeld, R. L., Frongillo, E. A., Weke, E., Dworkin, S. L., Pusateri, K., Shiboski, S., Scow, K., Butler, L. M., & Cohen, C. R. (2015). Shamba Maisha: Randomized controlled trial of an agricultural and finance intervention to improve HIV health outcomes. Aids (london, England), 29(14), 1889–1894. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000781

- Wohl, A. R., Garland, W. H., Wu, J., Au, C. W., Boger, A., Dierst-Davies, R., Carter, J., Carpio, F., & Jordan, W. (2011). A youth-focused case management intervention to engage and retain young gay men of color in HIV care. AIDS Care, 23(8), 988–997. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2010.542125