ABSTRACT

Men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately affected by HIV. Given that over 70% of MSM meet sexual partners via dating apps, such apps may be an effective platform for promoting HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use. We aimed to describe preferences among MSM for PrEP advertisements displayed on dating apps. We conducted individual in-depth interviews with 16 MSM recruited from a mobile sexual health unit in Boston, Massachusetts. Two focus groups were also held: one with mobile unit staff (N = 3) and one with mobile unit users (N = 3). Content analysis was used to identify themes related to advertisement content and integration with app use. Mean participant age was 28 (SD 6.8); 37% identified as White and 63% as Latinx. 21% of interviews were conducted in Spanish. Preferences were organized around four themes: (1) relevant and relatable advertisements, (2) expansion of target audiences to promote access, (3) concise and captivating advertisements, and (4) PrEP advertisements and services as options, not obligations. MSM are supportive of receiving information about PrEP on dating apps, but feel that existing advertisements require modification to better engage viewers. Dating apps may be an underutilized tool for increasing PrEP awareness and knowledge among MSM.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Sixty-seven percent of new HIV cases in the United States in 2021 occurred among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2023a). HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) prevents HIV acquisition and is available in oral and injectable formulations (Antoni et al., Citation2020; Grant et al., Citation2010; Landovitz et al., Citation2021). Black and Latinx MSM are disproportionately affected by HIV, yet rates of PrEP uptake are as low as 22% in some of these communities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Finlayson, Citation2019; Singh et al., Citation2018; Sun et al., Citation2022; Taggart et al., Citation2020). Moreover, in 2020, only 9% of Black individuals and 16% of Hispanic/Latinx individuals who could benefit from PrEP received a prescription (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2021c). PrEP uptake among diverse MSM must increase to reduce HIV incidence (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2021c; Garrison & Haberer, Citation2021).

Dating apps may be an effective platform for promoting PrEP, given that over 70% of MSM meet sexual partners via dating apps (Chow et al., Citation2016; Huang et al., Citation2016; Lampkin et al., Citation2016). Studies suggest MSM who use dating apps are more likely to engage in behaviors associated with sexually transmitted infection (STI) acquisition, including condomless anal intercourse, using recreational drugs before sex, or having greater than three sexual partners per year (Gibson et al., Citation2022). Others have shown that MSM using dating apps are more likely to test positive for STIs than peers not using such platforms (Hoenigl et al., Citation2020). When comparing PrEP advertisements on social media versus dating apps, dating apps have been shown to recruit MSM with higher HIV risk, (Bezerra et al., Citation2022) and dating app users are twice as likely to initiate PrEP compared to non-users (Hoenigl et al., Citation2020). Hence, PrEP advertisements on dating apps may reach MSM who are both higher risk for HIV acquisition and more likely to initiate PrEP (Goedel et al., Citation2016). For these reasons, advertisements for PrEP on dating apps and other platforms are of increasing interest to public health authorities, sexual health clinics, and health care providers (Ard et al., Citation2019; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2023b; Dehlin et al., Citation2019).

Sexual health messaging on dating apps is feasible and acceptable to MSM (Hecht et al., Citation2022). Amongst a group of young Black MSM in Baltimore, the majority discussed PrEP on dating apps but many did not have accurate information (Fields et al., Citation2021). Others have shown that advertising on dating apps can increase MSM attendance at sexual health clinics and can be used to distribute HIV self-testing kits (Rosengren et al., Citation2016; Ubrihien et al., Citation2020). In a survey of 457 MSM recruited via dating apps, 64% regarded apps as an acceptable source for sexual health information (Sun et al., Citation2015). Moreover, dating apps capture information about users’ geographic location, which could be harnessed to provide information about local sexual health resources (Card et al., Citation2018).

Effective PrEP-related messaging on apps must be appealing to viewers, yet preferences among MSM for such advertisements are not well described; existing descriptions have predominantly sampled English-speaking users. One study found that MSM prefer casual language rather than medical terms when receiving sexual health information on apps (Biello et al., Citation2021). Others have found that MSM desired sexual health information on dating apps that is engaging, positive in tone, not too clinical, focused on building social norms, and delivered by trusted organizations (Kesten et al., Citation2019). An online survey of MSM in Australia found preferences for PrEP advertisements with images of people, statistics about PrEP, rewards for seeking further information, and calls-to-action such as “Do it now!” (Fidler et al., Citation2023). We aimed to further describe preferences and desired content for PrEP advertisements displayed on dating apps among MSM. To our knowledge, this is the first of such studies to include Spanish speakers.

Methods

Study participants

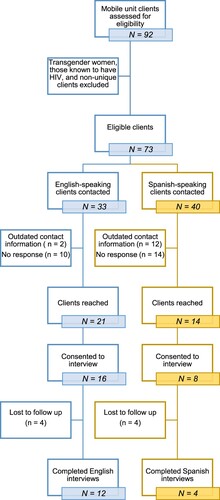

Methods are presented in accordance with COREQ guidelines (Appendix) (Tong et al., Citation2007). We recruited study participants from a mobile unit that offers sexual health services in Boston, Massachusetts (Chamberlin et al., Citation2023). This mobile unit holds clinics on weekend nights outside of LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, plus other sexual minority groups) venues including bars and clubs, or at community events (e.g., Pride celebrations) and offers sexual health services at no cost to patients. Participants were recruited from a convenience sample of mobile unit users who identified as MSM between January 2019 and February 2020. Two research assistants trained in qualitative methods contacted eligible individuals to explain the goals of the research and assess interest in participation. summarizes the enrollment process. Two focus groups were held: one with mobile unit staff (N = 3) and one with mobile unit users (N = 3). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and participant scheduling conflicts, we pivoted from additional focus groups to individual interviews of interested participants (N = 16).

Data collection

We developed semi-structured interview and focus group guides informed by existing literature on barriers to PrEP uptake and dating app use among MSM, investigators’ experiences providing PrEP and sexual health services, and domains derived from the Gelberg-Andersen Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (Andersen, Citation1995; Gelberg et al., Citation2000). This theoretical model was selected due to its multi-faceted representation of health behaviors and applicability to circumstances surrounding dating app and PrEP use, in addition to preferences for public health messaging. Its domains include pre-disposing, enabling, and need factors, which lead to health behaviors and outcomes. Within these domains, we considered variables including perceived barriers to sexual health care, community resources, health behaviors, health beliefs, and ability to navigate health services, given their relevance to understanding how non-facility-based resources (including dating apps) may support PrEP uptake. Open-ended questions focused on use of dating apps, attitudes toward PrEP promotion on dating apps, and preferences for content of PrEP advertisements on dating apps. Sample interview questions are shown in . Participants were also asked about barriers to accessing sexual health services and experiences using the mobile unit; those findings have been presented elsewhere (Chamberlin et al., Citation2023). Sociodemographic data were collected from mobile unit users but were not collected from mobile unit staff to protect confidentiality (). Participants received 20 dollars remuneration. Individual interviews lasted 30–60 min and were conducted online due to COVID-19. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish, depending on the participant's preferred language. Spanish language interviews were conducted by a fluent speaker. Focus groups lasted 1–2 h; the mobile unit staff focus group was conducted through an audio-only Zoom call and the mobile unit user focus group was conducted in person in a private conference room. Study procedures were approved by the Mass General Brigham Human Research Committee (Protocol 2019-P003021, Boston, MA) and are in accordance with the standards outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1. Interview topics and sample questions.

Table 2. Participant demographics (N = 19).

Analysis

Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded, transcribed, and translated when needed from Spanish to English. Using a content analysis method, we generated a codebook using an inductive and deductive approach; this codebook was then imported into Dedoose software (version 9.0.46). Two coders double-coded three (>10%) of the eighteen transcripts (sixteen individual interviews, two focus groups) and completed code application training tests in Dedoose to ensure inter-rater reliability (O’Connor & Joffe, Citation2020). During the training tests, one coder was presented with an excerpt of text coded by the opposite coder, but blinded to the codes previously applied. The coder completing the training test then applied codes to the excerpt. Areas of agreement and disagreement between coders were highlighted within Dedoose, which were then discussed by the two coders until agreement was reached. Categories and subcategories outlined in the codebook were continually reexamined to check for applicability and consistency in codebook interpretation. The remaining transcripts were then independently coded. Key themes were derived from the data and are presented below.

Results

Participant characteristics

Mean participant age was 28; 37% identified as White, 26% as mixed race, and 63% as Latinx. All identified as male. Twenty-six percent of participants were currently taking PrEP and an additional 47% had previously used PrEP. Half of participants were registered with dating apps at the time of interview and 94% had ever used dating apps. Sixty-three percent of participants had either an associate's or bachelor's degree. Twenty-one percent of interviews were conducted in Spanish.

Qualitative results

While thematic saturation was not reviewed in real time, we assessed the likelihood of saturation using principles described by Guest et al. and found that thematic saturation was achieved after seven interviews (Guest et al., Citation2020). We identified four themes that exemplify the preferences for PrEP advertisements on dating apps among this sample of MSM: (1) relevant and relatable advertisements, (2) expansion of target audiences to promote access, (3) concise and captivating advertisements, and (4) PrEP advertisements and services as options, not obligations. A summary of these themes is presented in .

Table 3. Themes, definitions, and representative quotes.

Relevant and relatable advertisements

Participants desired PrEP advertisements that were tailored to them as individuals, as opposed to generic advertisements that did not feel relatable. In the words of one participant, “The ads that I see, I’m just not drawn to them because they just look so general. There's nothing that catches my eye” (Participant 1, age 23, White, not Latinx). Participants suggested that different users should be shown different advertisements, consistent with their age, race, gender, and geographic location. One participant highlighted that when creating advertisements intended to be viewed across genders and sexual orientations, the advertisements must reflect this: “When you’re including everybody, your focus words would be different … like, ‘This one is made for men looking for men. This one's made for men and women looking for the opposite sex’” (Participant 6, age 28, mixed race, not Latinx).

The potential impact of location-specific advertisements was also commonly cited. With regards to desired information about local sexual health resources, one participant stated, “‘If you need condoms, if you need information, we’ll be here at these times’ … I think that would be super helpful” (Participant 9, age 30, mixed race, Latinx). Another participant noted that geolocation data could be harnessed to present viewers with sexual health resources that are relevant to their current location:

Dating apps really make sense because with the location-based aspect of it, that way you’re targeting your advertising outreach to people who are physically close by, who are much more likely to show up than doing other types of advertising where you don't necessarily know the geographic group that you’re targeting. (Mobile unit staff focus group participant)

Expansion of target audiences to promote access

While those interviewed felt that MSM on dating apps would benefit from PrEP advertisements, they also hoped that such advertisements would be shown to a broader audience of individuals at risk for HIV. As expressed by one participant, “People think [PrEP] is only for gay men, so I think it would be good to like put women, trans, trans women, trans men, everyone like in one photo” (Participant 16, age 27, White, Latinx). Expansion to specifically include heterosexual individuals was also frequently mentioned. One participant hoped that advertisements on apps could specifically focus on people of color, stating,

I feel like because people who are Black and Brown are very distrusting of a lot of health services. Just to be able to have more accurate information instead of going by what your friend says would be a little bit more helpful. (Participant 10, age 33, mixed race, Latinx)

Others thought advertisements should reach MSM who do not consider themselves part of the LGBTQIA+ community, as such individuals may use dating apps to discreetly find sexual partners:

Men who don't necessarily identify with the LGBT community or as gay … are harder to reach and we’re not going to find them necessarily out and about at [gay] venues, but they have also missed out on all of the education around safe sex that people who identify as gay or LGBT – that's kind of baked in to the culture. (Mobile unit staff focus group participant)

Concise and captivating advertisements

For PrEP advertisements to be effective, they must be appealing to viewers, clear, concise, and should not promote distrust or stigma. When asked about desired formatting for PrEP advertisements, the most common preference was for simple, bullet-point style advertisements. In the words of one individual, “I want to see single-word answers to my questions. I want to see four bullet points: free, safe, accessible, start tomorrow” (Participant 5, age 30, White, not Latinx). Another participant said “Queer people are very blunt. We’ll take the numbers just in an ad. It doesn't have to be so designed and fabricated” (Participant 7, age 23, White, not Latinx).

Participants had a broad range of preferences for PrEP advertisement content. Desired content included the purpose of taking PrEP, medication safety and side effects, next steps for obtaining a prescription, lists of local providers who prescribe PrEP, and lists of local HIV testing sites and hours. There was a clear preference to avoid overly-sexualized content. For example, one participant commented,

I think a lot of companies go down the road of using either shirtless models or men or pictures … They probably think it's a smart marketing move to grab your attention … but I think it probably leads to a decline in trust or engagement with the company. It seems almost like a cheap marketing trick. (Participant 2, age 25, White, not Latinx)

PrEP advertisements and services as options, not obligations

While participants were supportive of PrEP being advertised on dating apps, they wanted to avoid feeling forced to engage with advertisements or take PrEP. One participant noted,

I always felt like I was kind of pushed to get [PrEP] or something … Every ad that I’ve seen, or a lot of them, they talk about just being on PrEP as kind of like being a social obligation to society. I don't see it as a social obligation or a social necessity … it's personal. (Participant 3, age 28, “other” race, Latinx)

It was uncommon for participants to support “pop-up” or other types of advertisements which require viewers to interact with the advertisement to continue using the app. Some individuals feared such advertisements might dissuade users from continuing to use dating aps: “If you don't want to see it, you’re not going to use the app anymore. It's not going to work” (Mobile unit user focus group participant). Similarly, another participant shared that on apps geared toward arranging sexual encounters, people are “not wasting time reading ads” and “get mad” when advertisements pop up (Participant 13, age 33, mixed race, Latinx). Hence, PrEP advertisements on dating may be best executed through opt-in and invitation-based approaches rather than compulsory viewing.

Discussion

In our sample of MSM in Boston, participants had largely positive attitudes toward continuing to develop PrEP advertisements for dating apps. This support was evident across races and ethnicities, suggesting that apps may be an avenue for continuing to promote PrEP awareness and uptake among diverse groups of MSM. For advertisements to be effective, participants suggested that they must be relevant and relatable, targeted toward broad audiences, concise and captivating, and present services as options, not obligations.

The importance of dating apps as an avenue for public health messaging toward LGBTQIA+ individuals is underscored by the decline in physical spaces for this community. For example, between 2007 and 2019 in the United States, the number of gay bars is estimated to have declined by 59.3% and lesbian bars by 51.6% (Mattson, Citation2019). This trend will likely be exacerbated by new anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation in recent years and has been further potentiated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Choi et al., Citation2022; Goller et al., Citation2022; Human Rights Campaign, Citation2023; Powell & Powell, Citation2022). Hence, online spaces such as dating apps may become an increasingly effective means of raising awareness about PrEP and HIV prevention strategies as physical venues to disseminate such information continue to decline in number.

Participants also suggested creating advertisement content with specific demographics of viewers in mind to increase relatability. Increased relatability of advertisements may not only augment PrEP awareness, but also willingness to take PrEP, given that viewers may be more able see themselves in those portrayed in the advertisements and better understand the information presented (Goedel et al., Citation2016; Ma et al., Citation2024; Torres et al., Citation2018, Citation2019). Location-specific content was commonly cited as a way to increase relevancy to viewers. Others have shown that location-specific advertisements on dating apps can increase rates of attendance and HIV testing at local sexual health clinics, and hence may hold promise for increasing rates of PrEP prescriptions at local health centers (Ubrihien et al., Citation2020). Moreover, geographically-based content could improve dissemination of PrEP information in rural areas, which have historically received less PrEP-related messaging compared to metropolitan parts of the United States (Owens et al., Citation2020).

Participants frequently stated that PrEP advertisements on dating apps should be tailored to a wider audience, as they perceived MSM to be the sole audience for most advertisements. This is supported by a recent content review of 60 dating apps in which only 15% contained any sexual health information and only 3% contained information intended for non-MSM audiences. There is a paucity of sexual health information on dating apps and what does exist is not broadly applicable to all who may be at risk for STIs and HIV. Additionally, participants supported expansion of racial and ethnic diversity in PrEP advertisements and creation of advertisements in multiple languages. Similar preferences have been demonstrated among LGBTQ+ adolescents and adults who work with or parent LGBTQ+ adolescents (Ma et al., Citation2024; Macapagal et al., Citation2022).

Those interviewed felt that existing PrEP advertisements could be made more appealing to viewers. For example, they preferred less sexualized advertisement content. Others have shown that Black sexual minority men and LGBTQ+ youth prefer less sexualized PrEP advertisement content; sexually explicit advertisements may reinforce stigma of PrEP users as promiscuous (Calabrese et al., Citation2023; Macapagal et al., Citation2022). Interviewees also emphasized the importance of concise and practical content. In agreement with our findings, others have shown a preference for PrEP visual advertisements with increased slogan simplicity and more normalizing language about PrEP (Kalwicz et al., Citation2023; Macapagal et al., Citation2022).

Unique to this study is the theme of PrEP advertisements and services as options, not obligations. With scale-up of public health messaging surrounding PrEP, it is conceivable that dating app users viewing such advertisements may experience social pressures to initiate PrEP. This social pressure may be compounded by forced-engagement advertising strategies in which app users are required to view or interact with PrEP advertisements to resume app use. This work highlights the potential detrimental impact of these strategies, including alienating viewers and fostering negative attitudes toward PrEP. Our findings favor opt-in approaches in which those ready and interested are able to engage with PrEP advertisements. Opt-in strategies have proven effective in other public health efforts. For example, opt-in advertisements and campaigns have been shown to reduce alcohol consumption and increase uptake of HIV testing (Baisley et al., Citation2012; Brennan et al., Citation2020). Moreover, while opt-out approaches reach larger audiences, the ability to opt-in to certain marketing messages may increase viewer engagement and preserve positive perception of these messages (Ghiloni, Citation2018; Kumar et al., Citation2014; Ligaraba et al., Citation2023; Soh et al., Citation2022).

This study has several strengths. The qualitative methods allowed for in-depth characterization of participants’ preferences, compared to a survey-based approach. Recruitment of participants from a mobile sexual health unit outside of LGBTQIA+ venues allowed for inclusion of individuals that may not have been reached by clinic-based recruitment methods. We recruited a greater proportion of Spanish speaking and non-White participants compared to prior studies with similar aims. Moreover, the use of focus groups with mobile unit users and staff complemented individual interviews and facilitated inclusion of diverse perspectives.

A limitation of this study is that interview transcripts were not analyzed while participants were still being recruited; however, this was mitigated by assessing the likelihood of reaching thematic saturation after interviews were completed (Guest et al., Citation2020). This study is also subject to sampling bias, as those who agreed to participate may differ from other MSM who declined to be interviewed. Additionally, the findings in this study only capture the perspectives of cisgender MSM and had few Black MSM. Future studies may benefit from greater inclusion of transgender individuals and Black MSM. The participants in this study are also highly educated, with 47% having received a bachelor's degree, while the United States national average is 34% (Mittleman, Citation2022). Several participants mentioned the need to advertise PrEP beyond the MSM community. Future studies could assess the acceptability and preferences for PrEP advertisements tailored to heterosexually active adults and people who inject drugs.

This qualitative research represents one of the few attempts to characterize the preferences for PrEP advertisements on dating apps among MSM and uniquely includes Spanish speaking individuals. MSM are supportive of receiving information about PrEP on dating apps, but feel that existing advertisements require modification. The preferences described here highlight the importance of continuing to calibrate PrEP public health messaging to optimize acceptability, expand viewership, and achieve maximum impact. Dating apps may be an underutilized tool for increasing PrEP awareness and knowledge among MSM.

caic-2023-07-0136-File006

Download MS Word (16.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Health Innovations, Inc. for their 25-year history of providing expert and innovative care to LGBTQIA+ community members in Massachusetts and for their collaborative efforts in recruitment of participants for this study. We also thank the Infectious Disease Division administrative staff at Massachusetts General Hospital for supporting this project. Finally, we thank the study participants for their thoughtful contributions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data sets generated and analyzed during this study are not publicly available to protect the confidentiality of our study participants. However, datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and contingent upon institutional review board approval for data sharing.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andersen, R. M. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137284

- Antoni, G., Tremblay, C., Delaugerre, C., Charreau, I., Cua, E., Rojas Castro, D., Raffi, F., Chas, J., Huleux, T., Spire, B., Capitant, C., Cotte, L., Meyer, L., Molina, J.-M., & ANRS IPERGAY Study Group. (2020). On-demand pre-exposure prophylaxis with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate plus emtricitabine among men who have sex with men with less frequent sexual intercourse: A post-hoc analysis of the ANRS IPERGAY trial. The Lancet HIV, 7(2), e113–e120. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30341-8

- Ard, K. L., Edelstein, Z. R., Bolduc, P., Daskalakis, D., Gandhi, A. D., Krakower, D. S., Myers, J. E., & Keuroghlian, A. S. (2019). Public health detailing for human immunodeficiency virus pre-exposure prophylaxis. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 68(5), 860–864. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy573

- Baisley, K., Doyle, A. M., Changalucha, J., Maganja, K., Watson-Jones, D., Hayes, R., & Ross, D. (2012). Uptake of voluntary counselling and testing among young people participating in an HIV prevention trial: Comparison of opt-out and opt-in strategies. PLoS One, 7(7), e42108. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042108

- Bezerra, D. R. B., Jalil, C. M., Jalil, E. M., Coelho, L. E., Netto, E. C., Freitas, J., Monteiro, L., Santos, T., Souza, C., Hoagland, B., Veloso, V. G., Grinsztejn, B., Cardoso, S. W., & Torres, T. S. (2022). Comparing web-based venues to recruit gay, bisexual, and other cisgender men who have sex with men to a large HIV prevention service in Brazil: Evaluation study. JMIR Formative Research, 6(8), e33309. https://doi.org/10.2196/33309

- Biello, K. B., Hill-Rorie, J., Valente, P. K., Futterman, D., Sullivan, P. S., Hightow-Weidman, L., Muessig, K., Dormitzer, J., Mimiaga, M. J., & Mayer, K. H. (2021). Development and evaluation of a mobile app designed to increase HIV testing and pre-exposure prophylaxis use among young men who have sex with men in the United States: Open pilot trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(3), e25107. https://doi.org/10.2196/25107

- Brennan, E., Schoenaker, D. A. J. M., Durkin, S. J., Dunstone, K., Dixon, H. G., Slater, M. D., Pettigrew, S., & Wakefield, M. A. (2020). Comparing responses to public health and industry-funded alcohol harm reduction advertisements: An experimental study. BMJ Open, 10(9), e035569. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035569

- Calabrese, S. K., Kalwicz, D. A., Dovidio, J. F., Rao, S., Modrakovic, D. X., Boone, C. A., Magnus, M., Kharfen, M., Patel, V. V., & Zea, M. C. (2023). Targeted social marketing of PrEP and the stigmatization of black sexual minority men. PLoS One, 18(5), e0285329. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285329

- Card, K. G., Gibbs, J., Lachowsky, N. J., Hawkins, B. W., Compton, M., Edward, J., Salway, T., Gislason, M. K., & Hogg, R. S. (2018). Using geosocial networking apps to understand the spatial distribution of gay and bisexual men: Pilot study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 4(3), e61. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.8931

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a). Volume 26, Number 1: Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2015–2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b). Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data United States and 6 dependent areas, 2019: Special focus profiles. Retrieved May 25, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-26-no-2/content/special-focus-profiles.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021c). PrEP for HIV prevention in the U.S. Retrieved November 23, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/fact-sheets/hiv/PrEP-for-hiv-prevention-in-the-US-factsheet.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023a). HIV surveillance report. Retrieved May 19, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-34/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023b). Conversation starters. Start Talking. Stop HIV. Retrieved June 30, 2023, from http://www.cdc.gov/actagainstaids/campaigns/starttalking/convo.html

- Chamberlin, G., Lopes, M. D., Iyer, S., Psaros, C., Basset, I. V., O’Connor, C., & Ard, K. L. (2023). “That was our afterparty”: A qualitative study of mobile, venue-based PrEP for MSM. BMC Health Services Research, 23, Article 504.

- Choi, E. P. H., Hui, B. P. H., Kwok, J. Y. Y., & Chow, E. P. F. (2022). Intimacy during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online survey examining the impact of COVID-19 on the sexual practices and dating app usage of people living in Hong Kong. Sexual Health, 19(6), 574–579. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH22058

- Chow, E. P. F., Cornelisse, V. J., Read, T. R. H., Hocking, J. S., Walker, S., Chen, M. Y., Bradshaw, C. S., & Fairley, C. K. (2016). Risk practices in the era of smartphone apps for meeting partners: A cross-sectional study among men who have sex with men in Melbourne, Australia. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 30(4), 151–154. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2015.0344

- Dehlin, J. M., Stillwagon, R., Pickett, J., Keene, L., & Schneider, J. A. (2019). #PrEP4Love: An evaluation of a sex-positive HIV prevention campaign. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 5(2), e12822. https://doi.org/10.2196/12822

- Fidler, N., Vlaev, I., Schmidtke, K. A., Chow, E. P. F., Lee, D., Read, D., & Ong, J. J. (2023). Efficacy and acceptability of ‘nudges’ aimed at promoting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use: A survey of overseas born men who have sex with men. Sexual Health, 20(2), 173–176. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH22113

- Fields, E. L., Thornton, N., Long, A., Morgan, A., Uzzi, M., Sanders, R. A., & Jennings, J. M. (2021). Young black MSM’s exposures to and discussions about PrEP while navigating geosocial networking apps. Journal of LGBT Youth, 18(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2019.1700205

- Finlayson, T. (2019). Changes in HIV preexposure prophylaxis awareness and use among men who have sex with men — 20 urban areas, 2014 and 2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(27), 597–603. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6827a1

- Garrison, L. E., & Haberer, J. E. (2021). Pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake, adherence, and persistence: A narrative review of interventions in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 61(5), S73–S86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.04.036

- Gelberg, L., Andersen, R. M., & Leake, B. D. (2000). The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: Application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research, 34(6), 1273–1302.

- Ghiloni, B. W. (2018). Got to get you into my life: A qualitative investigation into opt-in text marketing. Transnational Marketing Journal, 6(1), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.33182/tmj.v6i1.378

- Gibson, L. P., Kramer, E. B., & Bryan, A. D. (2022). Geosocial networking app use associated with sexual risk behavior and pre-exposure prophylaxis use among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men: Cross-sectional web-based survey. JMIR Formative Research, 6(6), e35548. https://doi.org/10.2196/35548

- Goedel, W. C., Halkitis, P. N., Greene, R. E., & Duncan, D. T. (2016). Correlates of awareness of and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men who use geosocial-networking smartphone applications in New York City. AIDS and Behavior, 20(7), 1435–1442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1353-6

- Goller, J. L., Bittleston, H., Kong, F. Y. S., Bourchier, L., Williams, H., Malta, S., Vaisey, A., Lau, A., Hocking, J. S., & Coombe, J. (2022). Sexual behaviour during COVID-19: A repeated cross-sectional survey in Victoria, Australia. Sexual Health, 19(2), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH21235

- Grant, R. M., Lama, J. R., Anderson, P. L., McMahan, V., Liu, A. Y., Vargas, L., Goicochea, P., Casapía, M., Guanira-Carranza, J. V., Ramirez-Cardich, M. E., Montoya-Herrera, O., Fernández, T., Veloso, V. G., Buchbinder, S. P., Chariyalertsak, S., Schechter, M., Bekker, L.-G., Mayer, K. H., Kallás, E. G., … iPrEx Study Team. (2010). Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(27), 2587–2599. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1011205

- Guest, G., Namey, E., & Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS One, 15(5), e0232076. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

- Hecht, J., Zlotorzynska, M., Sanchez, T. H., & Wohlfeiler, D. (2022). Gay dating app users support and utilize sexual health features on apps. AIDS and Behavior, 26(6), 2081–2090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03554-9

- Hoenigl, M., Little, S. J., Grelotti, D., Skaathun, B., Wagner, G. A., Weibel, N., Stockman, J. K., & Smith, D. M. (2020). Grindr users take more risks, but are more open to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pre-exposure prophylaxis: Could this dating app provide a platform for HIV prevention outreach? Clinical Infectious Diseases, 71(7), e135–e140. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz1093

- Huang, E. T.-Y., Williams, H., Hocking, J. S., & Lim, M. S. (2016). Safe sex messages within dating and entertainment smartphone apps: A review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(4), e124. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.5760

- Human Rights Campaign. (2023). Weekly roundup of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation advancing in states across the country. Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.hrc.org/press-releases/weekly-roundup-of-anti-lgbtq-legislation-advancing-in-states-across-the-country-3

- Kalwicz, D. A., Rao, S., Modrakovic, D. X., Zea, M. C., Dovidio, J. F., Magnus, M., Kharfen, M., Patel, V. V., & Calabrese, S. K. (2023). ‘There are people like me who will see that, and it will just wash over them’: Black sexual minority men’s perspectives on messaging in PrEP visual advertisements. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 25(10), 1371–1386. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2022.2157491

- Kesten, J. M., Dias, K., Burns, F., Crook, P., Howarth, A., Mercer, C. H., Rodger, A., Simms, I., Oliver, I., Hickman, M., Hughes, G., & Weatherburn, P. (2019). Acceptability and potential impact of delivering sexual health promotion information through social media and dating apps to MSM in England: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7558-7

- Kumar, V., Zhang, X., & Luo, A. (2014). Modeling customer opt-in and opt-out in a permission-based marketing context. Journal of Marketing Research, 51(4), 403–419. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.13.0169

- Lampkin, D., Crawley, A., Lopez, T. P., Mejia, C. M., Yuen, W., & Levy, V. (2016). Reaching suburban men who have sex with men for STD and HIV services through online social networking outreach: A public health approach. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 72(1), 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000930

- Landovitz, R. J., Donnell, D., Clement, M. E., Hanscom, B., Cottle, L., Coelho, L., Cabello, R., Chariyalertsak, S., Dunne, E. F., Frank, I., Gallardo-Cartagena, J. A., Gaur, A. H., Gonzales, P., Tran, H. V., Hinojosa, J. C., Kallas, E. G., Kelley, C. F., Losso, M. H., Madruga, J. V., … HPTN 083 Study Team. (2021). Cabotegravir for HIV prevention in cisgender men and transgender women. New England Journal of Medicine, 385(7), 595–608. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2101016

- Ligaraba, N., Chuchu, T., & Nyagadza, B. (2023). Opt-in e-mail marketing influence on consumer behaviour: A stimuli–organism–response (S–O–R) theory perspective. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2184244. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2184244

- Ma, J., Owens, C., Valadez-Tapia, S., Brooks, J. J., Pickett, J., Walter, N., & Macapagal, K. (2024). Adult stakeholders’ perspectives on the content, design, and dissemination of sexual and gender minority adolescent-centered PrEP campaigns. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 21(1), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00826-y

- Macapagal, K., Ma, J., Owens, C., Valadez-Tapia, S., Kraus, A., Walter, N., & Pickett, J. (2022). 64. #PrEP4Teens: LGBTQ+ adolescent perspectives on content and implementation of a teen-centered PrEP social marketing campaign. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(4), S34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.01.024

- Mattson, G. (2019). Are gay bars closing? Using business listings to infer rates of gay bar closure in the United States, 1977–2019. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 5, 237802311989483. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119894832

- Mittleman, J. (2022). Intersecting the academic gender gap: The education of lesbian, gay, and bisexual America. American Sociological Review, 87(2), 303–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031224221075776

- O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 160940691989922. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

- Owens, C., Hubach, R. D., Williams, D., Voorheis, E., Lester, J., Reece, M., & Dodge, B. (2020). Facilitators and barriers of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake among rural men who have sex with men living in the Midwestern U.S. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(6), 2179–2191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01654-6

- Powell, L., & Powell, V. (2022). Queer dating during social distancing using a text-based app. SN Social Sciences, 2(6), 78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00345-4

- Rosengren, A. L., Huang, E., Daniels, J., Young, S. D., Marlin, R. W., & Klausner, J. D. (2016). Feasibility of using GrindrTM to distribute HIV self-test kits to men who have sex with men in Los Angeles, California. Sexual Health, 13(4), 389. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH15236

- Singh, S., Song, R., Johnson, A. S., McCray, E., & Hall, H. I. (2018). HIV incidence, prevalence, and undiagnosed infections in U.S. men who have sex with men. Annals of Internal Medicine, 168(10), 685–694. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-2082

- Soh, Q. R., Oh, L. Y. J., Chow, E. P. F., Johnson, C. C., Jamil, M. S., & Ong, J. J. (2022). HIV testing uptake according to opt-in, opt-out or risk-based testing approaches: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 19(5), 375–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-022-00614-0

- Sun, C. J., Stowers, J., Miller, C., Bachmann, L. H., & Rhodes, S. D. (2015). Acceptability and feasibility of using established geosocial and sexual networking mobile applications to promote HIV and STD testing among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 19(3), 543–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0942-5

- Sun, Z., Gu, Q., Dai, Y., Zou, H., Agins, B., Chen, Q., Li, P., Shen, J., Yang, Y., & Jiang, H. (2022). Increasing awareness of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and willingness to use HIV PrEP among men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis of global data. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 25(3), e25883. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25883

- Taggart, T., Liang, Y., Pina, P., & Albritton, T. (2020). Awareness of and willingness to use PrEP among Black and Latinx adolescents residing in higher prevalence areas in the United States. PLoS One, 15(7), e0234821. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234821

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Torres, T. S., De Boni, R. B., de Vasconcellos, M. T., Luz, P. M., Hoagland, B., Moreira, R. I., Veloso, V. G., & Grinsztejn, B. (2018). Awareness of prevention strategies and willingness to use preexposure prophylaxis in Brazilian men who have sex with men using apps for sexual encounters: Online cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 4(1), e11. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.8997

- Torres, T. S., Konda, K. A., Vega-Ramirez, E. H., Elorreaga, O. A., Diaz-Sosa, D., Hoagland, B., Diaz, S., Pimenta, C., Bennedeti, M., Lopez-Gatell, H., Robles-Garcia, R., Grinsztejn, B., Caceres, C., Veloso, V. G., & ImPrEP Study Group. (2019). Factors associated with willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis in Brazil, Mexico, and Peru: Web-based survey among men who have sex with men. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 5(2), e13771. https://doi.org/10.2196/13771

- Ubrihien, A., Stone, A. C., Byth, K., & Davies, S. C. (2020). The impact of Grindr advertising on attendance and HIV testing by men who have sex with men at a sexual health clinic in Northern Sydney. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 31(10), 989–995. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462420927815

Appendix

Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ): 32-item checklist.