ABSTRACT

Digital health technology interventions have shown promise in enhancing self-management practices among adolescents living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (ALHIV). The objective of this scoping review was to identify the preferences of ALHIV in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) concerning the use of digital health technology for the self-management of their chronic illness. Electronic databases, including PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (Plus with Full Text), Central (Cochrane Library), Epistemonikos, and Medline (EbscoHost), were searched. The review focused on English articles published before June 2023, that described a technology intervention for ALHIV specifically from LMIC. The screening and data extraction tool Covidence facilitated the scoping review process. Of the 413 studies identified, 10 were included in the review. Digital health technology interventions can offer enhanced support, education, and empowerment for ALHIV in LMICs. However, barriers like limited access, stigma, and privacy concerns must be addressed. Tailoring interventions to local contexts and integrating technology into healthcare systems can optimize their effectiveness.

Review registration: OSF REGISTRIES (https://archive.org/details/osf-registrations-eh3jz-v1)

Sustainable Development Goals:

Introduction

The burden of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) among adolescents in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is a pressing public health concern (Francis et al., Citation2023). The LMICs, are classified by the World Bank based on Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. According to this classification, low-income countries have a GNI per capita of $1,045 or less, such as Uganda, while middle-income countries have a GNI per capita between $1,046 and $12,695, such as Guatemala (Lencucha & Neupane, Citation2022; WorldBank, Citationn.d.). LMICs, particularly in the African region, contribute significantly to the global HIV epidemic, accounting for around 60% of new infections (WHO, Citation2023). Adolescents living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (ALHIV) in LMICs face formidable challenges, including limited access to healthcare, stigma, discrimination, lack of education, and inadequate support systems (Calabrese et al., Citation2023; Crowley et al., Citation2023; Kisesa & Chamla, Citation2016; The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, Citation2022). Unique structural hurdles, like the lack of electricity, technology, and affordable internet access, compound these challenges (Chory et al., Citation2022). Effective self-management is vital for these adolescents, involving tasks like adhering to antiretroviral therapy, monitoring viral load, attending medical check-ups, making lifestyle changes, and seeking psychosocial support (Abiodun et al., Citation2021; Crowley & Rohwer, Citation2021; O. Ivanova et al., Citation2019). With the rise of digital health technology, including mobile health apps, text messaging, and online platforms, new opportunities emerge to empower ALHIV in managing their condition (Butcher & Hussain, Citation2022; Goldstein et al., Citation2023). To address the unique preferences of ALHIV in LMICs towards digital health technology, understanding these preferences is crucial, shaped by factors like benefits, barriers, and facilitators (Dyer & Jai, Citation2013). A preliminary search on databases like MEDLINE and PubMed revealed no scoping or systematic reviews on this topic, highlighting the need for a comprehensive scoping review. A scoping review was chosen as the most suitable method to explore the preferences of ALHIV in LMICs regarding digital health technology for self-management. By systematically mapping existing literature, this review aims to provide insights into preferred digital health interventions, as well as the perceived benefits, barriers, and facilitators associated with their use. This research will fill a critical gap in our understanding of how digital health technology can better support ALHIV in LMICs.

Methods

The scoping review was conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for scoping reviews and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Peters et al., Citation2020; Tricco et al., Citation2018). The review was registered with OSF REGISTRIES (eh3jz-v1) on 25 June 2023.

Search strategy

For the main comprehensive search conducted on 27 June 2023 the databases included were PubMed, CINAHL (Plus with Full Text), Central (Cochrane Library), Epistemonikos, and Medline (EbscoHost). The search strategy, including all identified keywords and index terms, was adapted for each included database and information source. Key search terms were identified by Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and the search strings were developed to search the databases as indicated in Box 1. These search strategies were validated by an information specialist. The reference list of all included sources of evidence was screened for additional studies.

(((("Adolescent" OR "adolescence" OR "young people" OR "youth" OR "young adults" OR "teen" OR "teenager") AND ("Human Immunodeficiency Virus" OR "AIDS Virus" OR "AIDS" OR "HIV")) AND ("Developing Countries" OR "LMICs" OR "Third-World Countries" OR "Low income countries" OR "Middle income countries")) AND ("Information and Communications Technology" OR "ICT" OR "Technology" OR "Technology Enabled" OR "Technology based" OR "gaming" OR "social media" OR "eHealth" OR "mHealth" OR "WhatsApp" OR "SMS" OR "mobile" OR "internet" OR "text message" OR "telemedicine")) AND ("self-Management" OR "self-care" OR "self-regulation" OR "self-monitoring" OR "self-directed care" OR "self-efficacy" OR "treatment adherence" OR "treatment-taking behaviour" OR "medication adherence" OR "risk behaviour" OR "adherence behaviour" OR "adherence")

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

This scoping review included the population of ALHIV, whose ages range from 10 to 24 years (Sawyer et al., Citation2018). The primary objective was to examine the landscape of digital interventions designed for the purpose of self-management among this demographic. The review encompassed studies conducted within LMICs, involving participants from these regions. The scope of the review included a variety of research methodologies, including qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies, to comprehensively address the topic. To ensure the feasibility of analysis, only studies with full-text availability in the English language were considered within the scope of this review. The eligibility criteria are depicted in .

Table 1. Eligibility criteria.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that solely examined the perspectives of family members or healthcare professionals were excluded, as the aim is to capture the experiences of ALHIV themselves. Additionally, studies that do not address self-management or the use of digital technology were excluded, as they are not directly relevant to the research question. Systematic reviews that included articles on ALHIV and technology-related interventions were not included.

Study selection

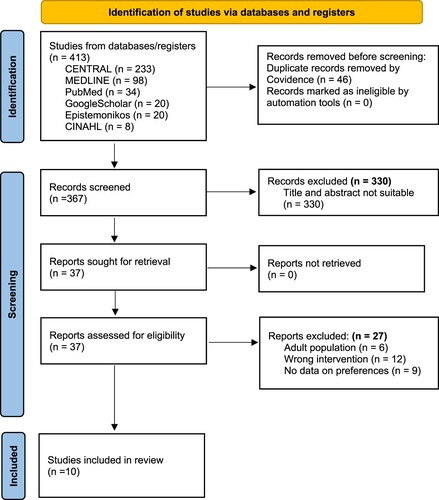

After the search, all identified citations was collated and uploaded into Covidence and the duplicates were removed. A total of 367 studies were screened by two independent reviewers for assessment against the inclusion criteria for the review. All disagreements that arose between the reviewers at each stage of the selection process were resolved through discussion. From this process a PRISMA diagram was developed, see .

Data extraction

For this scoping review, data was extracted by one reviewer from the 10 included papers using a data extraction tool in Covidence developed and piloted by that reviewer and another reviewer. The extracted data included participant details, the investigated concept, study context, research methods, and key findings. The findings were extracted according to the benefits, barriers, facilitators, and preferences. The data extraction template is provided (see Appendices 1 and 2).

Data analysis and presentation

The data analysis and presentation for this scoping review involves a narrative summary of the findings, ensuring alignment with the review objective and question (Mak & Thomas, Citation2022; Peters et al., Citation2015; Peters et al., Citation2021). In addition to the narrative, tables were utilized to demonstrate the key findings and patterns identified in the literature.

Results

The search results, as evidenced in the PRISMA diagram (), yielded 413 articles. After title and abstract screening, 10 articles were considered for full text review. See below for the completed PRISMA diagram.

Study characteristics

The included studies, totalling 10, encompassed a range of LMICs (). The preponderance of these studies, specifically nine out of 10, was concentrated in Africa, namely Uganda, Kenya, South Africa and Nigeria, and one in Central America namely Guatemala. The study designs comprised five randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and five non-randomized controlled trials, with both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods employed. In total, 1223 participants participated in the reviewed studies.

Table 2. Study characteristics.

Technology types used by ALHIV for self-management in LMIC

Studies were conducted over the span of 2015–2021, employing diverse digital technologies such as Short Message Service (SMS), WhatsApp and similar messaging applications, web-based platforms, and Facebook.

SMS interventions

Five studies (Abiodun et al., Citation2021; Hacking et al., Citation2019; MacCarthy et al., Citation2020; Rana et al., Citation2015; Sánchez et al., Citation2021) employed SMS interventions. SMS facilitates text messaging between devices without the need for the internet (Ashraf, Citation2019). Some studies combined SMS with electronic medication monitoring systems, like the Wisepill device (MacCarthy et al., Citation2020), to enhance medication adherence, but challenges in device maintenance and charging were noted.

Messenger applications

Three studies (Chory et al., Citation2022; Hacking et al., Citation2019; Henwood et al., Citation2016) used messenger applications, which require internet access and offer group communication functionality (Galip, Citation2022).

Web-based platforms

One study (Ivanova et al., Citation2019) employed a web-based platform that provided health information and interactions but was not primarily a social media platform.

Two studies (Dulli et al., Citation2018, Citation2020) used secret Facebook groups for intervention, accessible only through direct invitation and requiring internet access and compatible devices.

Perceived barriers to technology use in self-management

All ten studies provided examples of barriers that the participants encountered while engaging with the various digital health interventions. These barriers were grouped into the four broad categories: stigma and disclosure concerns, device accessibility, digital literacy and competing obligations. Some of these barriers influence each other and where they overlap they were listed under all relevant categories.

Stigma and disclosure concerns

Seven studies highlighted the significance of stigma and the fear of disclosure among ALHIV, a key concern raised by participants in Rana et al. (Citation2015) was that participants may be pressured by other people in their life to share the password to their health app or any coded messages (Abiodun et al., Citation2021; Chory et al., Citation2022; Dulli et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Hacking et al., Citation2019; MacCarthy et al., Citation2020; Rana et al., Citation2015).

Device accessibility

Eight studies cited accessibility as a barrier, including limited access to devices, cost of airtime and data, structural obstacles, and device sharing (Chory et al., Citation2022; Dulli et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Henwood et al., Citation2016; Ivanova et al., Citation2019; MacCarthy et al., Citation2020; Rana et al., Citation2015; Sánchez et al., Citation2021).

Digital literacy

Six studies noted the negative impact of participants’ weak digital literacy on interventions, including but not limited to lack of knowledge of how to reset passwords (Abiodun et al., Citation2021; Dulli et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Henwood et al., Citation2016; Ivanova et al., Citation2019; Sánchez et al., Citation2021).

Competing obligations

Three studies mentioned that participants’ other obligations, such as schoolwork and family responsibilities, hindered their engagement (Chory et al., Citation2022; Dulli et al., Citation2020; Sánchez et al., Citation2021).

Perceived facilitators of technology use in self-management

This section outlines the key facilitators, from the ten studies reviewed, of the participants’ engagement with digital health interventions. Facilitators are grouped into the four following categories: Overcoming Stigma and Disclosure Concerns, Device Accessibility, Digital Literacy, and Preferential Features.

Overcoming stigma and disclosure concerns

Four studies suggested techniques to mitigate stigma and disclosure concerns, such as secret Facebook groups, pseudonyms, and customizable notifications (Abiodun et al., Citation2021; Chory et al., Citation2022; Dulli et al., Citation2018, Citation2020).

Device accessibility

Nine studies proposed solutions to enhance accessibility, including low-cost options like SMS and social media, designing interventions for mobile devices, and addressing cost barriers (Abiodun et al., Citation2021; Chory et al., Citation2022; Dulli et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Hacking et al., Citation2019; Henwood et al., Citation2016; Ivanova et al., Citation2019; MacCarthy et al., Citation2020; Rana et al., Citation2015; Sánchez et al., Citation2021).

Digital literacy

One study recommended minimizing literacy requirements to facilitate participation (Henwood et al., Citation2016).

Preferential features

Participants in several studies appreciated coded messaging, engaging and varied content, two-way interaction, customizable notification timing and source of notifications, and virtual access to healthcare professionals (Abiodun et al., Citation2021; Chory et al., Citation2022; Dulli et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Hacking et al., Citation2019; Henwood et al., Citation2016; Ivanova et al., Citation2019; MacCarthy et al., Citation2020; Rana et al., Citation2015).

Perceived benefits of technology use in self-management

It is widely accepted by all ten studies reviewed that utilisation of technology has many benefits for the ALHIV participating in an intervention. This section summarises the key benefits identified in the studies reviewed.

Accessibility

According to five studies, the use of digital technology to roll out a health intervention expands the potential reach of the intervention to participants who may not have access to conventional interventions (Abiodun et al., Citation2021; Dulli et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Rana et al., Citation2015; Sánchez et al., Citation2021). The technology intervention can be tailored to minimize costs for the participants and thus improve accessibility through affordability according to four studies (Chory et al., Citation2022; Henwood et al., Citation2016; Ivanova et al., Citation2019; Rana et al., Citation2015).

Confidentiality

Seven studies illustrated that technology allows for customization to meet the privacy needs of the intervention participant, such as coding of the sender’s details and information received (Abiodun et al., Citation2021; Chory et al., Citation2022; Dulli et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Hacking et al., Citation2019; MacCarthy et al., Citation2020; Rana et al., Citation2015).

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to explore the preferences of ALHIV in LMIC regarding the use of digital health technology for self-management of their chronic illness. As there are no existing studies on this specific topic these “preferences” had to be extracted, interpreted and inferred from existing studies that indirectly touched on this topic. This analysis was done by examining ten different interventions through the lens of the four sub-questions types of technology utilized, barriers, facilitators and benefits identified by the participants and researchers. These findings have revealed several preferences, their foundation and examples for their potential implementation.

Medication reminders, such as SMSs or notifications through this review emerged as a preferred feature. This preference is rooted in its ability to help ALHIV adhere to treatment regimens and improve health outcomes (MacCarthy et al., Citation2020; Rana et al., Citation2015). These notifications and messages should be customizable, ensuring relevant information and reminders tailored to their specific needs (Abiodun et al., Citation2021).

Educational content about HIV management as a preference stems from enhancing their knowledge and empowerment to make informed decisions (Hacking et al., Citation2019; Henwood et al., Citation2016; Ivanova et al., Citation2019; Rana et al., Citation2015). Educational material should be varied and engaging, including multimedia and video elements, as it keeps them motivated and active in their self-management (Chory et al., Citation2022; Henwood et al., Citation2016; Ivanova et al., Citation2019; Rana et al., Citation2015).

Privacy settings as a core feature are preferred as these settings allow them to control who accesses their health-related information, protecting their confidentiality and reducing potential stigma (Abiodun et al., Citation2021; Chory et al., Citation2022; Dulli et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Hacking et al., Citation2019; MacCarthy et al., Citation2020; Rana et al., Citation2015). This feature can be implemented through pseudonyms or nicknames and coding the information that is provided through notifications. This includes but is not limited to the sender’s details and the content (Chory et al., Citation2022; Dulli et al., Citation2018, Citation2020). It is strongly recommended not to implement password protection for the digital application. Password-protected information may raise suspicions for parents, teachers or partners, potentially leading to unintended consequences. Moreover, considering the limited digital literacy among ALHIV, password protection can become a significant obstacle. In situations where ALHIV forget their password, this security measure could hinder their ability to access the intervention. Therefore, to facilitate accessibility and privacy, avoiding password protection is advised (Rana et al., Citation2015).

ALHIV highly value interactive features such as discussion forums and live chats with healthcare professionals. These features enable them to seek guidance, engage in peer support, and enhance their sense of community (Abiodun et al., Citation2021; Chory et al., Citation2022; Dulli et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Hacking et al., Citation2019; Henwood et al., Citation2016; Ivanova et al., Citation2019; MacCarthy et al., Citation2020; Rana et al., Citation2015).

Lastly, clear and simple user interfaces are essential for ease of use, particularly for ALHIV with limited digital literacy (Henwood et al., Citation2016).

These preferences underscore the importance of aligning digital interventions with the diverse needs and expectations of ALHIV in LMICs to enhance their health and well-being. Although the included studies were from LMICs, the perceived barriers and facilitators can likely be generalised to other countries. Understanding and incorporating these preferences can lead to more effective and user-friendly digital health solutions for this vulnerable population. Starting digital health programs for ALHIV requires customization, privacy measures, interactive features, user-friendly design and continuous evaluation to enhance adherence, empower users, ensure confidentiality and support self-management (Canali et al., Citation2022; Lazard et al., Citation2021).

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights the potential preferences ALHIV have for digital health interventions. Nevertheless, challenges like technology access, stigma, and privacy hamper wide adoption. Tailored interventions mitigating ALHIV's unique challenges are crucial. Enhancing digital literacy, affordability, and healthcare system integration is essential. Continuous evidence-based evaluation and adaptation are key to bolstering technology's role in ALHIV self-management, necessitating further research to optimize its impact.

Acknowledgements

This scoping review was done towards a master’s in nursing degree by L.W.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abiodun, O., Ladi-Akinyemi, B., Olu-Abiodun, O., Sotunsa, J., Bamidele, F., Adepoju, A., David, N., Adekunle, M., Ogunnubi, A., Imhonopi, G., Yinusa, I., Erinle, C., Soetan, O., Arifalo, G., Adeyanju, O., Alawode, O., & Omodunbi, T. (2021). A single-blind, parallel design RCT to assess the effectiveness of SMS reminders in improving ART adherence among adolescents living with HIV (STARTA Trial). Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(4), 728–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.11.016

- Ashraf, F. (2019). The impact of texting (SMS) on students academic writing. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications (IJSRP), 9(3), 8710. https://doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.9.03.2019.p8710

- Butcher, C. J. T., & Hussain, W. (2022). Digital healthcare: The future. Future Healthcare Journal, 9(2), 113–117. https://doi.org/10.7861/fhj.2022-0046

- Calabrese, S., Perkins, M., Lee, S., Allison, S., Brown, G., Jean-Philippe, P., Chakhtoura, N., Moye, J., & Kapogiannis, B. G. (2023). Adolescent and young adult research across the HIV prevention and care continua: An international programme analysis and targeted review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 26(3), e26065. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.26065

- Canali, S., Schiaffonati, V., & Aliverti, A. (2022). Challenges and recommendations for wearable devices in digital health: Data quality, interoperability, health equity, fairness. PLOS Digital Health, 1(10), e0000104. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000104

- Chory, A., Callen, G., Nyandiko, W., Njoroge, T., Ashimosi, C., Aluoch, J., Scanlon, M., McAteer, C., Apondi, E., & Vreeman, R. (2022). A pilot study of a mobile intervention to support mental health and adherence among adolescents living with HIV in Western Kenya. AIDS and Behavior, 26(1), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03376-9

- Crowley, T., Petinger, C., Nchendia, A. I., & van Wyk, B. (2023). Effectiveness, acceptability and feasibility of technology-enabled health interventions for adolescents living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032464

- Crowley, T., & Rohwer, A. (2021). Self-management interventions for adolescents living with HIV: A systematic review. BMC Infectious Diseases, 21(1), 431. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06072-0

- Dulli, L., Ridgeway, K., Packer, C., Murray, K. R., Mumuni, T., Plourde, K. F., Chen, M., Olumide, A., Ojengbede, O., & McCarraher, D. R. (2020). A social media–based support group for youth living with HIV in Nigeria (SMART connections): Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e18343. https://doi.org/10.2196/18343

- Dulli, L., Ridgeway, K., Packer, C., Plourde, K. F., Mumuni, T., Idaboh, T., Olumide, A., Ojengbede, O., & McCarraher, D. R. (2018). An Online support group intervention for adolescents living with HIV in Nigeria: A pre-post test study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 4(4), e12397. https://doi.org/10.2196/12397

- Dyer, J. S., & Jai, J. (2013). Preference theory. In S. I. Gass, & M. C. Fu (Eds.), Encyclopedia of operations research and management science. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1153-7_787

- Francis, F., Robertson, R. C., Bwakura-Dangarembizi, M., Prendergast, A. J., & Manges, A. R. (2023). Antibiotic use and resistance in children with severe acute malnutrition and human immunodeficiency virus infection. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 61(1), 106690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2022.106690

- Galip, K. (2022). What’s up with WhatsApp? A critical analysis of mobile instant messaging research in language learning. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 6(2), 352–365. https://doi.org/10.33200/ijcer.599138

- Goldstein, M., Archary, M., Adong, J., Haberer, J. E., Kuhns, L. M., Kurth, A., Ronen, K., Lightfoot, M., Inwani, I., John-Stewart, G., Garofalo, R., & Zanoni, B. C. (2023). Systematic review of mHealth interventions for adolescent and young adult HIV prevention and the adolescent HIV continuum of care in low to middle income countries. AIDS and Behavior, 27(S1), 94–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03840-0

- Hacking, D., Mgengwana-Mbakaza, Z., Cassidy, T., Runeyi, P., Duran, L. T., Mathys, R. H., & Boulle, A. (2019). Peer mentorship via mobile phones for newly diagnosed HIV-positive youths in clinic care in Khayelitsha, South Africa: Mixed methods study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(12), e14012–e14012. https://doi.org/10.2196/14012

- Henwood, R., Patten, G., Barnett, W., Hwang, B., Metcalf, C., Hacking, D., & Wilkinson, L. (2016). Acceptability and use of a virtual support group for HIV-positive youth in Khayelitsha, Cape Town using the MXit social networking platform. AIDS Care, 28(7), 898–903. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1173638

- Ivanova, O., Wambua, S., Mwaisaka, J., Bossier, T., Thiongo, M., Michielsen, K., & Gichangi, P. (2019). Evaluation of the ELIMIKA Pilot Project: Improving ART adherence among HIV positive youth using an eHealth intervention in Mombasa, Kenya. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 23(1), 100–110. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2019/v23i1.10

- Kisesa, A., & Chamla, D. (2016). Getting to 90-90-90 targets for children and adolescents HIV in low and concentrated epidemics: Bottlenecks, opportunities, and solutions. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, 11(Suppl 1), S1–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/COH.0000000000000264

- Lazard, A. J., Babwah Brennen, J. S., & Belina, S. P. (2021). App designs and interactive features to increase mHealth adoption: User expectation survey and experiment. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(11), e29815. https://doi.org/10.2196/29815

- Lencucha, R., & Neupane, S. (2022). The use, misuse and overuse of the ‘low-income and middle-income countries’ category. BMJ Global Health, 7(6), e009067. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009067

- MacCarthy, S., Wagner, Z., Mendoza-Graf, A., Gutierrez, C. I., Samba, C., Birungi, J., Okoboi, S., & Linnemayr, S. (2020). A randomized controlled trial study of the acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary impact of SITA (SMS as an Incentive To Adhere): A mobile technology-based intervention informed by behavioral economics to improve ART adherence among youth in Uganda. BMC Infectious Diseases, 20(1), 173–173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-4896-0

- Mak, S., & Thomas, A. (2022). Steps for conducting a scoping review. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 14(5), 565–567. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-22-00621.1

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In E. Aromataris, & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Colquhoun, H., Garritty, C. M., Hempel, S., Horsley, T., Langlois, E. V., Lillie, E., O'Brien, K. K., Tuncalp, Ö, Wilson, M. G., Zarin, W., & Tricco, A. C. (2021). Scoping reviews: Reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

- Rana, Y., Haberer, J., Huang, H., Kambugu, A., Mukasa, B., Thirumurthy, H., Wabukala, P., Wagner, G. J., & Linnemayr, S. (2015). Short message service (SMS)-based intervention to improve treatment adherence among HIV-positive youth in Uganda: Focus group findings. PLoS One, 10(4), e0125187. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125187

- Sánchez, S. A., Ramay, B. M., Zook, J., de Leon, O., Peralta, R., Juarez, J., & Cocohoba, J. (2021). Toward improved adherence: A text message intervention in an human immunodeficiency virus pediatric clinic in Guatemala City. Medicine, 100(10), e24867–e24867. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000024867

- Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(3), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- UNAIDS. (2022). IN DANGER: UNAIDS global AIDS update 2022. J. U. N. P. o. HIV/AIDS. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2022-global-aids-update_en.pdf

- WHO. (2023). Data on the size of the HIV epidemic. Retrieved June 17, from https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/data-on-the-size-of-the-hiv-aids-epidemic?lang=en

- WorldBank. (n.d.). World Bank country and lending groups. Retrieved July 4, from https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups