ABSTRACT

An essentialist, ‘traditional', Maasai gender ideology that poorly reflects the day-to-day gender realities of residents is being reproduced and dominating in the modern schooling setting of a Maasai community in Southern Kenya. Through an ethnographic analysis based on long-term fieldwork and mixed-method approaches, this paper explores the construction of this gender ideology as reflected in schooling aspirations of parents, teachers, and students, in students’ own constructions of masculinity and femininity, and in school culture. This ideology functions to promote education as a means of cultural preservation and livelihood protection by drawing schooling into the Maasai's unique age-set system and warrior tradition, which is heavily imbued with particular gender constructions. While, arguably, maintaining this traditional ideology may conflict with broader goals of empowerment and social equity for Maasai women, it may serve to facilitate schooling for young girls, off-set increasing and burdensome responsibilities, and provide them with an attainable femininity.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The crowd, comprising primary school students, teachers, and a few international guests from a small non-profit organisation supporting educational programmes in this community, is quieted as a young Maasai girl and boy step forward into the clearing. In unison they introduce their play. ‘Welcome honourable guests, teachers, and fellow students. This is a Maasai play called “Early marriage”, performed to you by the AS club. Thank you.’ The actors begin to dramatise the story of a young Maasai girl, named Sampatita, who is taken out of school by her father to marry a man of his choice. She is rescued as her wedding approaches and sent to boarding school to complete her education. Her father and groom are sent to prison. Many years later they are brought into court and are surprised to find that the presiding judge is Sampatita herself. She sets them free and they all join the campaign in support of girls’ education.

The crowd applauds and the actors take a bow. In haste, they step back out of the clearing. In the distance you can already hear the faint grunts of a traditional male dance troupe approaching. A tall young school boy, dressed as a warrior with shining jewellery and a club in hand, steps forward to introduce the group. ‘Welcome honorable guests, teachers, and fellow students. This is a Maasai traditional dance called “The Cow I like Most”, performed for you by the AS club.’ A line of male dancers has entered the clearing; the presenter takes his place among them and with choreographed precision they move in and out of a variety of configurations, steadily bobbing up and down, revealing their uniforms underneath their traditional attire. The lead singer sings of the importance of cattle to the Maasai and how they need to be used to pay for education so that the Maasai can continue to fight to protect their land.

The drama depicts two strong rights-based social movements that play somewhat contradictory roles in the re-fashioning of gender norms in a changing society. The first, the drama of early marriage, illustrates the presence of a global women's rights movement, which aligns itself against the perceived traditional patriarchy of the Maasai social system, fighting for girls to be treated equitably. The second, the male traditional dance song within the modern school setting, illustrates the local presence of a global indigenous rights movement, which aligns itself with the free expression of cultural heritage and integrity and the protection of ‘traditional’ livelihoods. From a non-local perspective these may be perceived as forces that collide. A women's rights activist on-looker may be disconcerted with the thought that the girls’ dramatic pleas to a more gender-equitable Maasai society are followed by a ‘traditional’ male warrior dance that enacts a gendered social order in which young men (as warriors) are given the role and responsibility to protect the livestock economy. Such a ‘traditional’ representation, they may fear, might reinforce a patriarchal gender system where women's roles are primarily relegated to the domestic sphere and thus impact girls’ achievements and life opportunities.

Yet at the local level, these performances seem quite ‘natural’ together. They illustrate a process of human rights vernacularisation (Merry Citation1996), wherein global rights discourses enter local normative frameworks and conceptualisations of social justice and are negotiated, transformed, and redefined accordingly. This convergence of both global indigenous rights and women's rights discourses with local priorities around formal education, livelihood diversification and enhancement, and political and economic development has resulted in the (re)production of a dominant ‘traditional’ gender ideology in the school, one that not only associates girls and women to the domestic sphere and boys and men to the political and economic realm, but does so in a context where such an alignment poorly reflects contemporary gendered realities in the broader community.

Based on long-term ethnographic fieldwork in the community of Elangata Wuas in Southern Kenya, this article investigates how, why, and with what possible implications an essentialist ‘traditional', gender ideology is being emphasised and enacted in the school setting. It is argued that indigenous rights discourses have helped to realign formal schooling from antagonistic to Maasai culture to essential for cultural preservation. In doing so, schooling has been integrated into the Maasai's age-set system, as a necessary stage through which both young boys and girls must pass to achieve manhood and womanhood. Rather than challenging notions of Maasai masculinity and femininity, formal schooling is now perceived as an important institution through which the essential values and attributes associated with ‘traditional’ manhood and womanhood are cultivated. While this is most apparent in the case of young boys, as the popular slogan ‘school is the spear of today’ evidently replaces the traditional warriorhood institution with formal schooling, it is no less true for young girls, for whom schooling is popularly believed to bestow upon them the skills and dispositions to nurture and care for their families. The implications of this process are uncertain. While on the one hand, there is the risk that such constructions limit young girls’ capabilities and life choices, on the other hand, it may facilitate the entry of young rural Maasai girls into school and it may offer them a notion of femininity that is readily attainable. In this respect it may protect young girls from the frustrations that befall young Maasai boys who struggle to attain this form of ‘traditional’ masculinity, with its breadwinning and leadership roles that largely hinge on successful job market outcomes in an ultra-competitive economic environment. Furthermore, young schoolgirls may employ this essentialised construction of gender to lighten their loads, so to speak, by shifting back to men duties and responsibilities they find burdensome.

The social life of rights and gender identities in primary school

Within the growing sub-field of an anthropology of human rights, much attention has been placed on the need to understand ‘the social life of rights’ (Wilson Citation2006). Human rights are actively created as global rights discourses get channelled, mediated, and transformed while passing through transnational networks, state systems and institutions, civil society, local communities, and various social actors (Goodale and Merry Citation2007). Anthropological work has demonstrated the complex arena of negotiation as rights concepts articulate with a plurality of other normative repertoires found in, for example, statutory, customary, and religious laws or local social norms (Merry Citation2006). Commonplace strategies of forum shopping, combining and consolidating different elements from one set of claims or concepts to another, result in a hybrid and dynamic normative system (Goodale Citation2009). This approach provides an important framework for considering how educational rights, women's rights, and indigenous rights are being appropriated and enacted at the intersection of a rapid uptake in primary schooling and broader community concerns and predicaments around changing notions of development, modernity, livelihoods, poverty, marginality, and cultural integrity. It helps elucidate how through a process of vernacularisation a new gendered normative order is produced in an effort to both maintain cultural integrity and to advance education for both boys and girls.

This study also draws from an expansive and rich literature on the complexity of gender constructions and identities in the early and primary school setting (i.e. Blaise Citation2005; Martin Citation2011; Paechter Citation2007; Renold Citation2005; Skelton and Francis Citation2003). In particular, it builds on several key findings; that young children in school navigate a complex and sometimes even contradictory repertoire of gendered identities, including multiple gendered identities (Allan Citation2009; Renold Citation2004), that young students can and will strategically employ multiple identities, sometimes simultaneously and other times enacting different identities for different contexts or at different times (Paechter and Clark Citation2015), and that it is crucial to understand what such identities mean for the children who enact them, particularly if one is interested in the broader implications of this on identity politics and gendered norms (Paechter Citation2012). Paechter (Citation2012) voices an important caution against presuming that certain typical, ‘dominant’ forms of masculinity are necessarily hegemonic in that they work to subordinate girls and women. She calls on future studies to scrutinise the forms, meanings, and the operation of dominant, subordinate, resistant, transgressive, or altogether different forms of masculine and feminine identities. Advancing this call, this study provokes important questions on the implications of these newly constructed gender norms. Is the (re)production of a ‘traditional’ gender ideology in Maasai classrooms, one that appears to reflect a seemingly patriarchal social order, in practice hegemonic? Is it internalised by schoolgirls in such a way that it limits or undermines their ambitions, choices, and achievements? Or, alternatively, might it be strategically invoked to lessen the social pressure of unattainable femininities or to resist the on-set of burdensome responsibilities that belong, they could argue, to the boys?

Setting and methods

Elangata Wuas, the predominantly Maasai community which features as the central site of this study, is a former group ranch that stretches over 200,000 acres in the southern district of Kajiado and is home to approximately 10,500 residents. It is ecologically typical of a semi-arid rangeland. Low altitudes, variable and little rainfall, and poor soils combine to produce an environment with little agricultural potential. Consequently, the community depends largely on livestock husbandry as their primary economic activity but, like other Maasai communities, supplements animal husbandry with a wide range of other income-generating pursuits (Homewood, Kristjanson, and Trench Citation2009).

The recent privatisation of Elangata Wuas, from communal management to individual freehold titles, has produced considerable changes in livestock holdings and grazing strategies as well as opening up new types of income-generating opportunities for residents, including renting and selling grass and other natural resources held in private holdings. It has also supported a rapid increase in school participation. There is little infrastructure in water provision, no electricity, and no paved roads in Elangata Wuas but the growing commercial centre of Mile 46 has a recently erected mobile phone network, dozens of new small businesses, churches, residential homes, and nursery schools, as well as an expanded health centre and a new library, which has been recently equipped with the first computer lab and internet facility in the region.

This study follows from long-term ethnographic engagement in the community of Elangata Wuas, starting in 2003 when the author first pursued two years of doctoral fieldwork on the topic of education, gender, and social change. Multiple methods were employed, including extensive participant observation in the community and as a volunteer English teacher in one of the local primary schools. Through this role, students were regularly assigned essay assignments on various topics. During this period of research more than 60 interviews were conducted among teachers, parents, students, and non-schooling members of the community on a wide range of topics with a specific focus on issues around the role of education, gender, and social change. In 2005 a household survey of 135 families was administered. This survey collected a series of basic socio- economic and demographic characteristics along with a focus on education and attitudes towards schooling.

This period of doctoral fieldwork was followed by an eight-year inter-disciplinary research programme investigating the causes and consequences of tenure change in nine communities, including Elangata Wuas, across the Maasai rangelands of Southern Kenya. This programme was initiated in 2007 and is still on-going. This research programme has illuminated fascinating dynamics related to changes in gender roles and responsibilities related to changing tenure and livelihood strategies. In 2008–2009 a second round of longitudinal household survey was conducted, tracking and interviewing families that were part of the 2005 survey.

A third research initiative in Elangata Wuas, initiated in 2011 and still on-going, looks specifically at gender dimensions of tenure transformation and incorporates a wide variety of methods, mostly semi-structured interviewing and 14 in-depth family case studies. As part of this research programme extensive interviewing is on-going in preparation of a monograph on gender and development in Elangata Wuas. Apart from drawing new insights on the subject, I have also been using this opportunity to verify and ensure that insights used here from earlier data collection efforts are still relevant today.

‘We now know the benefits of education’: a schooling transition

Decades ago formal education was, and for some still is, believed to be wholly transformative of Maasai culture. For this reason, amongst others, Maasai parents were very reluctant to send their children to school (Holland Citation1998; Saitoti Citation1986; Sena Citation1986). Boys were to grow to become the new leaders of the community. Sending boys to school led to their forsaking their training as warriors, a training that would teach them the important qualities of manhood: self-discipline, courage, strength, and cooperation, apart from the enormous responsibility of protecting and replenishing livestock. Schoolboys, it was believed, would grow to know nothing about cattle and would even lose their love for cattle. They would find employment elsewhere and forget their homes and their communities, their traditions and responsibilities. As such, colonial authorities thought school was a critical institution for developing the Maasai and boarding schools could be used to quell the threat emanating from the Maasai's military culture (King Citation1972; Sena Citation1986). Officials with the assistance of local chiefs periodically raided homes forcing families to send at least one boy to school. These boys became social outcasts, as school was not the activity of a ‘real’ Maasai man. Older generations of schooled men retell stories about how they were constantly teased and called names by their brothers and age mates for going to school.

School to the Maasai was a bad thing, a place where children were taught alien ideas incompatible with Maasai values, a place where people were indoctrinated and got lost, and misbehaved like irmeek, as we called them. Irmeek were all who were not Maasai, strangers who were despised by our people. (Saitoti Citation1986, 53)

Parents also retell how the worst children, those who were not good at herding, were the ones to be sent to school and how parents took their schooling children to diviners to erase their classroom learning and school experiences from their memory. Parents reflect back on this amusingly, as if it was far in the past. ‘We didn't know the benefit of education.’

Survey data on schooling in Elangata Wuas shows a dramatic and relatively recent increase in school participation within the community. The 2008 survey data indicate that 85% of boys and 87% of girls between the ages of 7 and 14 were currently schooling at the time of the surveyFootnote1. In the age group above them, those aged 15–24 years at the time of the survey, 77% of boys and 54% of girls had ever attended school. As the cohorts get older fewer people have ever attended school. What has also changed remarkably is the gender distribution of schooling children. For the first time gender parity has been reached among the youngest generation of children. In fact, at those ages girls even outnumber boys in schooling. In all other cohorts the percentage of men who have attended at least one year of primary school far out-numbers the percentage of women.

The change in school participation has been brought about by numerous factors, which have been explored in more detail elsewhere. Of critical importance has been the increased integration of Maasai into the Kenyan state, with demographic and economic implications that have contributed to an overwhelming sense that Maasai are becoming increasingly marginalised, neglected, and that the viability of their pastoral livelihoods, a central marker of Maasai identity, for future generations is rapidly diminishing. Simultaneously, Maasai have also been integrated into global networks and civil society movements focused on women, children, and indigenous rights. These forces have converged, implicating education and gender in interesting ways at the local level. As demonstrated below, education has been re-aligned with cultural rights, no longer to be viewed as antagonistic to Maasai culture but rather viewed as one of the only ways in which Maasai can protect their livelihoods, and by extension their identity and culture, from further encroachment. This has been a gendered process, as the unique age-set system of the Maasai, which is heavily embedded with particular gender constructions, has become one of the main socio-cultural institutions used metaphorically to draw connections between the role of education and Maasai livelihood security and cultural rights.

‘The pen is the spear of today’: education for cultural preservation

Education is widely viewed as critical in personal and social development, the provision of freedom, and the fostering of life choices. Formal schooling is believed to be a central mechanism through which the poor can escape poverty and tradition as it is associated with greater economic development, significant health improvements, and increases in peace and security (Cremin and Nakabugo Citation2012; Switzer Citation2013; UNESCO Citation2010). The Kenyan government strongly emphasises the role of education in fostering a sense of nationhood and preparing all Kenyan citizens for industrial take-off and modernisation (Republic of Kenya Citation1999). Female education, more specifically, is believed to enhance women's empowerment by broadening their horizons of possibility and giving them more decision-making control to take up opportunities outside of the domains traditionally mandated to them (Ames Citation2013; Kabeer Citation2005; Tembon and Lucia Citation2008). It follows from these perspectives that education offers young Maasai men and women an escape from their ‘traditional’ pastoral livelihoods and ‘traditional’ culture.

Interestingly, local discourses produced by Maasai NGOs and educated elites shift the global framework from escapism to survival, as they emphasise the role that education will play in Maasai's livelihood protection and cultural preservation. Maasai need to educate their children in order to save themselves as a community. Educated Maasai will take up positions of influence in government so as to ensure that the Maasai have voice and support for their interests. According to Sena (Citation1986), such a shift in discourse among local leaders was already taking shape shortly after independence. He writes that, at that time, a key issue among local leaders was to stress the importance of formal education and other development initiatives ‘which were seen as a means of protecting the Maasai against agriculture and administrative encroachment and to better defend Maasai prerogatives within the national socio-political and economic system’ (Sena Citation1986, 72). However, it is likely that this discourse was importantly popularised by the unprecedented growth of non-governmental organisations in Africa in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and specifically a flourishing Maasai-run civil society (Igoe Citation2003).

The message is strongly relayed, in meetings and workshops, and on other occasions, that the Maasai need to take a stand and to make leaders of their men. In the past, as an informant explained to me, leadership was not dependent on formal education. Village leaders, spokesmen of age-sets, and other traditional leaders were chosen based on their success in family life, their physical appearances, and their skills at oration. But today, in the words of an informant, ‘to be a real leader you must have education'. As Maasai feel increasingly integrated into the nation state, the urgency of having intermediaries that are literate in the discourse of politics and government becomes essential. Most Maasai NGOs take this position, arguing that they can better achieve what they need as a community when they have a voice among the political and economic elite.

The prominent Maasai author, Kulet (Citation1971), writes that it is not only possible but also imperative that the new generation of Maasai holds the spear in one hand and the pen in the other. ‘The pen is the spear and the book is the shield of today’ is a popular expression used in various contexts to remind young people that education is the new warriorhood and the only effective way to secure Maasai pastoral livelihoods and preserve Maasai culture. By drawing the metaphor of protection to the pen through the spear, the book through the shield, this discourse of education as self-protection appeals to the Maasai's unique age-set system and warrior tradition, which is heavily imbued with particular gender constructions.

‘Women are growing horns’: gender dynamics

Among the Maasai, gender roles and expectations are importantly framed in relation to maturation and position within the life course. For men, the Maasai age-set system organises men into cohorts of age-mates who pass through various stages of their lives together through ritual promotion beginning with circumcision. Prior to entering their age-set, young boys are given responsibilities to herd and look after livestock. Once they are deemed ready for manhood, they are circumcised with other fellow age-mates and become murrans (warriors), traditionally entrusted as protectors of the community. In the past, murrans defended the community from attacks, accumulated livestock through raiding, learned the art of governing, and helped with herding. They would live apart from their families, in large settlements (emanyatta) with their age-mates and would have to follow strict dietary, sexual, and social restrictions aimed at fostering discipline, self-denial, and community consciousness. After a period of approximately seven years, murrans are ritually promoted to junior elders, at which point they should marry, start a family, and provide for them economically. Their command over community political leadership augments as they become full elders and firestick elders, ritually responsible for a new age-set. Lastly, they retire into the venerable state of ancient elders. The ritual cycle of new age-sets occurs approximately every 15 years although recently the cycles have shifted considerably.

While females are not ritually promoted through the age-set system, many of their social relationships are defined through this system and they too experience shifting gender roles as they go through the life cycle. Young girls also herd and care for livestock as well as assisting mothers with a whole series of household-based chores, including sweeping, cooking, fetching water and firewood, washing clothes, milking, cleaning gourds, beading, constructing houses, and caring for younger siblings. Initiation into womanhood is traditionally recognised through female circumcision, followed soon after by marriage. Young women's responsibilities and leadership in matters of the home and community shift in relation to the growth of their family. These are marked by their own set of titles that confer their authority and status; entito for young and uncircumcised girls, esiankiki for those circumcised, entomoni for those married with young children, enkitok for adult women, and koko for old grandmothers.

Seeing gender roles and expectations through this ‘traditional’ institution of the age-set/life course system harkens back to a long contested public/private gendered dichotomy (Moore Citation1988; Rosaldo Citation1980; Rosaldo and Lamphere Citation1974) and a critique of the pervasive view of the ‘pastoral patriarch’ (Hodgson Citation2000). Not only is the distinction between a female-private and male-public dichotomy questioned (Rasmussen Citation2000; Talle Citation1988) but in contexts where it appears to structure traditional gender ideology and divisions of labour, like the Maasai, it is argued that it is a recent phenomenon, a product of particular historical circumstances, and not inherent to pastoralism (Hodgson Citation1999, Citation2000). Among the Maasai there is a literature, already decades ago, on the ways in which Maasai men and women's roles and relationships have changed over time, suggesting that in the post-colonial period Maasai women have lost considerable control in multiple domains of social, political, economic, and spiritual life (Hodgson Citation1999, Citation2000, Citation2001; Kipuri Citation1989; von Mitzlaff Citation1988; Talle Citation1988).

If seeking to understand gender roles and responsibilities from the actions of men and women on the ground in Elangata Wuas, you would find little support for this popular ‘traditional’ representation. Today, in light of the dramatic increases in school participation that have brought children who were previously herding the family livestock into the classroom, wives find themselves to be among the principal persons responsible for herding livestock (Archambault Citation2014). This has also been facilitated by changes in land tenure, from communal holdings to the privatisation of individual parcels, which has reduced the mobility of animals and provided women with the ‘opportunity’ of herding livestock close to the home while still fulfilling their many household duties. Women have also taken up a great variety of income-generating activities, some of which have become possible due to land privatisation (charcoal production, selling of grass, small cultivation, and selling of produce). Very recent data collected in March 2013 reveal that women run an overwhelming majority of small business enterprises in the towns of Elangata Wuas (Prossomariti Citation2013). These businesses include shops, restaurants, pubs, salons, and money transfer stations (Mpesa Points), among others. As families and households diversify, women are playing an active role as critical breadwinners in the family. In a similar vein, women are heavily involved in community and national politics, organising campaigns and demonstrations over different political issues. They are very active in civil society, in various social, political, and religious groups, and in the women's and indigenous rights movements. For example, as explored within a series of 16 recent (2015) and lengthy interviews (each on average 2.5 hours in length) in preparation for the book, women in ELW have organised protests against alcohol consumption in Elangata Wuas town centres and have mobilised and evicted (by force and on foot) hundreds of Somali camels and their herders from Elangata Wuas land. Young women from the community, particularly those who have undertaken secondary studies, have also become quite politically active on social media in efforts to safeguard natural resources and to advocate for women's rights more generally (Archambault Citation2015). While some women are keen to be taking on these additional roles in livestock husbandry, entrepreneurship, or political activism, many express concern that they are overworked and taking on the responsibilities that husbands should bear. One could go as far as to say that there is a growing concern in Elangata Wuas of emasculation and the plight of Maasai men, with high levels of unemployment and alcoholism. In discussing how women were becoming very active in what is often considered traditional male domains, one middle-aged male research assistant exclaimed: ‘Women are growing horns!’

If indeed such a segregation of spheres is a relatively new and recent construction of gender roles and further such a construction does not resonate with current roles and responsibilities in daily life in Elangata Wuas, it is all the more alluring to find this essentialised, ‘traditional’ gender ideology being re-enacted and re-produced in the school setting.

‘Rain, rain, go away. This is mother's washing day’: gender in the school

Based on years of informal discussions and observations I have had with parents, teachers, and students, it appears that the discourse on the role of education in Maasai livelihood and cultural preservation indeed resonates locally and carries with it certain gendered expectations. In a series of more formal interviews I conducted in 2006 among 35 parents, I asked why they were sending their children to school. One of the most common justifications was that educated children could get jobs that would be helpful to their communities and their families. In line with the ‘traditional’ gendered implications of such narratives, when asked more specifically why it was important to educate boys, parents in Elangata Wuas commonly explained that education would provide boys with jobs, which were valued for obtaining positions of leadership. When asked about girls the emphasis shifted to a girl's ability to support her family and her parents. ‘They can do marvelous things for their parents after getting a good job.' The narratives around female education are especially noteworthy because in the past one of the main reasons parents claim to have not invested in girls’ education was because it was seen as a ‘lost’ investment, as the benefits would be accrued, in a patrilocal system, to her husband's family. It was remarkable to hear how often parents (of all different backgrounds) insisted that girls take much better care of their parents than boys and used this rationale to justify sending girls to school. ‘Girls remember to help their parents more than boys.’ ‘Girls [are more helpful] because boys end up drinking alcohol or doing drugs and going with prostitutes after getting good money.’ ‘Girls might help their parents as they love their parents more than boys.’ Such attitudes have also been found elsewhere in Kenya (Mungai Citation2002). Despite prevalent rights-based discourses around female education circulating in Elangata Wuas and within the school setting specifically, very few parents (only 3 out of 35 interviewed) employed an explicit rights discourse when justifying their reasons for sending their girls to school. Instead they relied on well-recognised and culturally accepted gendered normative frameworks integrated with indigenous rights discourse to effectively reach the same ends.

While interviewed parents unanimously claimed that girls and boys should both reach ‘the end of education', in-depth interviews with parents and teachers and students’ own essays on ‘My Future’ revealed gendered aspirations around occupations. For boys, consistent with the notion that men occupy roles of political leadership, good jobs included teachers, doctors, government officers, commissioners, and Presidents. For girls, consistent with a view that women are nurturing, they included teachers, nurses, and secretaries. During an NGO-sponsored prayer ceremony at an all-girls Maasai boarding school, the soon-to-be graduates were asked to share their career goals. When one young graduate declared she wished to be a politician, thunderous laughter from the audience ensued. Later in the staff room a heated discussion took place. ‘A politician! What was she thinking?’ one of the female teachers exclaimed. They all shook their heads in agreement, puzzled that the girl would pick such an inappropriate job for a Maasai lady. Elsewhere, in Western Kenya, Milligan (Citation2014) observes how teachers' attitudes and behaviours are gendered and can be quite derogatory for female students in secondary school.

Consistent with the ‘traditional’ gender ideology, schooling was talked about as a process that increased girls’ nurturing capacities. When asked if it is easier or more difficult for a primary educated girl to find a husband, a male schoolteacher answered, ‘It is easier … . Men think that those girls are more caring … ' Even more remarkable, when men and women were asked in a series of interviews on female education, what was the most important skill girls could be taught at school, they almost always listed practical domestic skills: ‘cooking, needlework, laundry work, first aid, “mother-craft”, care of the home, nutrition, child bearing, environment, agriculture, self-discipline, and respect.’ Only one elder man included ‘leadership qualities’ as an important skill for girls to learn in school.

Students themselves also seem to reproduce gender roles and responsibilities consistent with this ‘traditional’ gender ideology. In an effort to contribute children's own point of view on gender and sexuality (Myers and Raymond Citation2010), male and female students in grade 6, 7, and 8 were asked to write essays on ‘Maasai Women’ and ‘Maasai men'. Footnote2 Analysing these essays it became clear that there was an overwhelming consensus, between male and female students, on their gendered roles, responsibilities, and natures, even among this young and educated generation. As ‘second leaders in their homes', women were perceived as responsible for the home and care of the children. Responsibilities mentioned in essays included: building houses, feeding the family, looking after the children, carrying them, clothing them, changing them, watching them, looking after livestock, herding, milking, cooking, serving, cleaning, washing clothes and utensils, fetching water and firewood, helping pregnant mothers, preparing celebrations and running small businesses for income (marketing, charcoal burning, crafts, among others). ‘A family without a woman is like food without salt,’ one student wrote. ‘Without women there is no life,’ another offered. Women were presented as important, valued, and respected but often over-worked, mistreated, and abused by their husbands. Among all the essays there was not a single one in which women were cast in a negative light. The adjectives used to describe women included: beautiful, smart, sweet, respectful, clean, obedient, and disciplined. Their roles included: creator, supporter, provider, mid-wife, and healer. Any problems women had were almost always related to the irresponsibility or cruelty of men.

On the other hand, there was much more ambiguity regarding the nature of men. There was a sense of cruelty and greed in male representations, but at the same time a respect for their strength, bravery, and hard work. Not in a single essay were men described in affectionate terms. Many of the essays explicitly emphasised that men do not do domestic work. Apart from fencing around the compound, it was repeatedly claimed that men stay far away from the duties of women and spend little time in the home. Within the family they are considered the ‘house heads’, making all the decisions and not accepting to be challenged. Within the community, men were presented as providing security and peace, forming alliances through marriage arrangements, and mitigating conflicts between family and community members. Repeatedly, men were described as those who protect the land and community from strangers. Day-to-day activities of men included the herding of livestock, the watering of animals, digging wells, and spraying livestock with vaccines. Most of the essays mentioned that it was a man's exclusive right to sell livestock at the market. The money from livestock sales was supposed to be used to provide for all the family's needs. Men are expected to provide clothes, food, uniforms, and school fees. To fulfil these responsibilities men must look for work. Men's roles included: warriors, peacemakers, leaders, family heads, problem solvers, and providers.

The generic representations of men and women in Kenyan textbooks, as also recently observed by Foulds (Citation2013, Citation2014), also help to reinforce the association of men and women with their respective political and private domains. The Jomo Kenyatta Foundation series of textbooks offer grade one students a lesson about the roles of family members:Footnote3

What Father does. A father is the head of the house. Father is a tailor. Father is a fisherman. What mother does. Some mothers are housewives. Housewives do most of the work at home. Mothers care for the family. They also work outside the home. Mother is a doctor. Mother is a shop keeper. (Jomo Kenyatta Foundation Citation2003, 23–24)

Roles and Responsibilities of Family Members: Father: He is supposed to provide the following: (a) security, (b) food, (c) clothing, (d) shelter, (e) love. Mother: She is supposed to do the following: (a) Support the father in the provision of necessary commodities like food, clothing, health care and education. (b) Guide and counsel the children on good morals. This enables the children to become, well behaved, respectful, and good citizens. (c) She should show love to both her children and husband. This creates a good environment at home for the better growth of children. (Jomo Kenyatta Foundation Citation2005a, 193 emphasis added)

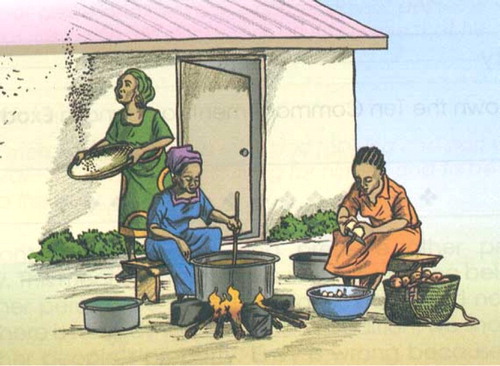

In both passages fathers are emphasised as providers, mothers as nurturing supporters. In textbook drawings, fathers are rarely depicted in the house or interacting with their children. They are disproportionately presented in professional occupations away from the home and rarely pictured doing ‘female’ household chores. Likewise, women in textbook images are disproportionately presented in the home, caring for children, cleaning the house, and cooking ( and ).

In the English textbook for grade one there is a telling song that pupils learn to sing: ‘Rain, Rain, Go Away. This is Mother's Washing Day. Come Again Another Day' (Jomo Kenyatta Foundation Citation2004, 54). When women do appear in professional capacities there is a fairly consistent range of female professions. Secretary, nurse/doctor, and policewoman are among the most common. The secretary is the typical female occupation. The nurse, doctor, and policewoman occupations are appropriate careers for women who are viewed as natural caretakers and moral authorities.

As has been shown in other African contexts (i.e. Dunne Citation2007), schools in Elangata Wuas are distinctly gendered in their management structures, in the use of space, in school relationships, and in student roles and responsibilities. In brief, male teachers hold most of the senior positions within schools, although this appears to be changing with a noticeable increase of headmistresses and female assistant head teachers. Student prefects, responsible for monitoring the behaviour of their fellow classmates, are usually positions occupied by senior boys.

In Elangata Wuas schools, boys and girls often play and socialise in separate spaces, as they do at home. They prefer to play games in sex-separated company and prefer to sit apart in the classroom if given the chance. Boys also tend to socially adhere to their age-set status among their schooling peers. Young circumcised men in the upper grades of primary school will usually only fraternise with their fellow age-mates. They tend to abide by some aspects of traditional food restrictions and only eat in the company of their mates and outside the view of female students. Some will also take advantage of their authority over the uncircumcised boys by making demands, teasing, or even bullying this younger generation.

With regard to teacher student gendered interactions, boys and girls have more intimate relationships with teachers of the same sex and try to practice mild avoidance with teachers of the opposite sex. They are punished differently and almost exclusively by teachers of the same sex.

Most obviously, the ‘traditional’ gender domains are reinforced through quite explicit sexually segregated roles and responsibilities in the school environment. These can be observed both from the distribution of chores within the school and the representation of gender roles in the standardised curriculum. Roles and responsibilities, with a few exceptions, largely coincide with the expectations that girls be in charge of the domestic domain and boys the political. Girls are primarily responsible for cooking for the school-feeding programme. Everyday, the cook, who is a volunteer mother from the community, is assisted by several female students with the preparation of the meal. These girls also assist in distributing the food to the long lines of students. Meanwhile, they also deliver plates of food to each of the members of the teaching staff. If anything is needed from the kitchen, girls are requested to go and fetch it. They also pick up the bowls and pots from the staff room and return them to the kitchen where they help clean up. Girls are also most commonly the ones taking care of the smaller children at school. When the nursery day has ended, small children seek the company of bigger girls, and when school is over, girls will often walk their younger siblings home.

It is difficult in the school setting, where most of the chores are of a domestic kind, to avoid boys’ involvement in ‘traditionally’ girls’ duties. As much as they can, boys’ duties often involve tasks of a manual nature. They will be asked to carry things. They will also be sent to the nearby town to purchase or deliver a request. They will be in charge of watering the plants on the compound and often, though a girls’ duty is in the home, of fetching water from the deep wells. The only food preparation process that male students participate in is the collection of firewood, which is a female chore within the home setting. They also monitor the feeding lines, maintaining the order of younger students. Alongside girls, boys are also expected to clean the compound, another duty that is normally considered out of their sphere and in a subtle way challenges the construction of the dominant ‘traditional’ gender ideology.

Conclusion: the functions and implications of gender essentialisms

This paper has explored how an essentialist, ‘traditional', Maasai gender ideology, which casts women as inherently nurturing and therefore primarily responsible for the domestic care of the family and home, and men as inherently rational and thus entrusted with political authority, economic production, and community leadership, is being reproduced in the modern, contemporary, school setting. This is reflected in parents’ gendered justifications for sending their daughters and sons to school, in students’ own gendered aspirations and representations of Maasai femininity and masculinity, and in the school culture of gendered interactions, roles, and responsibilities. Such a phenomenon is intriguing in a community context where gender roles and responsibilities have been dramatically changing, making evident that such ‘traditional’ representations do not reflect actual day-to-day gendered realities.

Then why is it that such an essentialist and misleading ideology is reproduced in the schooling context? It has been argued that the presence of this dominant ideology is the product of a convergence between a number of powerful and sometimes contradictory forces with local priorities. In Elangata Wuas, as in other Maasai communities in Kenya, population pressure, climatic instability, state neglect, encroachment by neighbouring groups, and the privatisation of land, among other forces, have threatened the viability of pastoral livelihoods for the young and future generations. Residents feel increasingly marginalised and impoverished as pastoralism plays a central role in economic security and socio-cultural identity. Under pressure, parents are turning to formal education for their young as a key tool in facilitating the pursuit of diversified livelihoods. Simultaneously parents feel pressure from the various rights-based social movements that have taken root through the growth of Maasai civil society organisations, various development interventions, and through state institutional channels such as the school. For example, the women's rights discourses advocate for equitable opportunities for the girl child, central of which is the plea for equal access to education. Amidst these pressures, and through strong influence from Maasai indigenous rights discourses, formal education for the Maasai has been recast not as a threat to Maasai culture, as it has historically been perceived, but rather as a central tool for its preservation. The popular slogan ‘the pen is the spear of today’ encapsulates both how education promises to politically and economically empower Maasai to fight for their rights and resources but also how education can be subsumed within a gendered socio-cultural order. School is the new institution through which young boys and girls can become men and women, and through which essential values and attributes of a ‘traditional’ masculinity and femininity can be respected, embraced, and cultivated rather than discarded. The accommodation of ‘traditional’ gender norms in Elangata Wuas primary schools has been importantly facilitated by Kenya's self-help, community-based education policy, which has locally embedded schools within their communities and which has supported school staffing by local teachers. That the majority of teachers in Elangata Wuas primary schools are Maasai is key to maintaining cultural consistency and familiarity. Maasai teachers speak Maa, the local mother tongue. They are themselves part of the age-set system and understand and respect the roles derived from this system. Importantly, they are also among the staunchest advocates for the need to educate the young generation in order to protect livelihoods and preserve Maasai identity.

What are the implications of reproducing such a ‘traditional’ gender ideology that is not only inaccurate to contemporary gender realities but appears to reflect a patriarchal social order? In this case, the dynamic and complex nature of ideologies themselves is revealed, as the ‘traditional’ gendered construction is incorporated into new ‘modern’ social settings such as the school and may actually help facilitate processes of education that are deemed inherently empowering to women by many. While the same ideological constructions in the past may have held children back, relegating girls to the home in pursuit of their domestic duties and consigning boys to warrior training, they are used today to send children to school, to perfect girls’ skills as mothers and daughters, and to make modern day warriors of young men. Instead of advocating for education through an explicit human rights or women's rights framework, the claims to schooling for both girls and boys are made within the register of indigenous group rights and livelihood and cultural protection. By enrobing education within a familiar socio-cultural gendered framework, parents’ fears of state indoctrination, assimilation, and ultimately the loss of culture and identity are appeased. The young generation gains both the rights to schooling and the rights to indigenous identity.

But does this come at a loss for the women's rights agenda? Some may still argue that, while the contemporary interpretation of the ideology may help girls (and boys) get into school, its persistence within the schooling environment will ultimately limit girls’ capabilities. A key question here, and one which needs further research attention, is to what extent are students influenced by this gender ideology (Paechter Citation2012)? Are girls actually internalising their socialisation into housewives, mothers, and secondary income-generators and boys their roles as family heads, primary bread-winners, and political leaders? The school environment is full of alternative performative acts that may bring about significant changes in gender norms; the girls’ leadership roles in the prefect system, the boys’ domestic labour around the school compound, and a new ‘Christian man’ narrative subtly rising from religious education (Jomo Kenyatta Foundation Citation2005b).

One might even consider the possibilities that this ‘traditional’ gender ideology may help young girls cope with the pressures of contemporary society. Today in Elangata Wuas it has become exceedingly difficult to translate schooling, for both boys and girls, into good employment. In some sense young women may be protected from the disappointments that befall young men, who find themselves unable to live up to such masculine ideals. As has been found in other African primary school contexts (i.e. Morojele Citation2011), unattainable masculinities can lead young men to withdraw from their families, refuse non-educated livelihoods, and take up alcohol in consolidation. In addition, girls and young women may strategically invoke this traditional discourse in order to help off-set the growing sets of responsibilities that are falling on women today and to encourage men to carry their weight. In this light, it becomes evident how the drama and the dance described in the opening vignette, seemingly contradictory performances, can so ‘naturally’ co-exist.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a doctoral fellowship from the Population Council and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council pursued at the Department of Anthropology at McGill University. The writing of this research was further supported by a VENI research grant from the Dutch Academy of Sciences (NWO). I would like to acknowledge my appreciation to the many research assistants and members of the Elangata Wuas community who supported this research.

Notes

1. Other sources of data, mainly trends in my earlier 2005 household survey, school enrollment data, and observational data of households corroborate these high rates of school participation.

2. During the period in which I volunteered as an English teacher in one of the primary schools in Elangata Wuas, I assigned my students this essay exercise. This was a closed textbook, free writing exercise for which I refrained from giving any further directions or examples beyond simply stating the topic. This way, I tried to ensure as much as possible that the ideas in the texts were their own. I received 181 compositions in total, 93 on Maasai women and 88 on Maasai men.

3. The textbook analysis for this paper uses the Jomo Kenyatta Foundation series of primary school textbooks because these are the series used in the local primary schools in Elangata Wuas at the time of the research. It is quite possible that other publishers frame gender differently to what is being presented here.

References

- Allan, A. J. 2009. “The Importance of Being a ‘Lady’: Hyper-Femininity and Heterosexuality in the Private, Single-Sex Primary School.” Gender and Education 21 (2): 145–158. doi: 10.1080/09540250802213172

- Ames, P. 2013. “Constructing New Identities? The Role of Gender and Education in Rural Girls’ Life Aspirations in Peru.” Gender and Education 25 (3): 267–283. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2012.740448

- Archambault, C. 2014. “Young Perspectives on Pastoral Rangeland Privatization: Intimate Exclusions at the Intersection of Youth Identities.” European Journal of Development Research 26 (2): 204–218. doi: 10.1057/ejdr.2013.59

- Archambault, C. 2015. “Facebook Feminism: Engendering Political Advocacy for Land and Natural Resource Rights through Social Media in Kenya.” Presented at the World Bank Land and Poverty Annual Conference, Washington DC, USA, March 23–27.

- Blaise, M. 2005. Playing it Straight: Uncovering Gender Discourses in the Early. New York: Routledge.

- Cremin, P., and M. G. Nakabugo. 2012. “Education, Development and Poverty Reduction: A Literature Critique.” International Journal of Educational Development 32: 499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.02.015

- Dunne, M. 2007. “Gender, Sexuality and Schooling: Everyday Life in Junior Secondary Schools in Botswana and Ghana.” International Journal of Educational Development 27 (5): 499–511. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2006.10.009

- Foulds, K. 2013. “The Continua of Identities in Postcolonial Curricula: Kenyan Students’ Perceptions of Gender in School Textbooks.” International Journal of Educational Development 33 (2): 165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.03.005

- Foulds, K. 2014. “Buzzwords at Play: Gender, Education, and Political Participation in Kenya.” Gender and Education 26 (6): 653–671. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2014.933190

- Goodale, M. 2009. Surrendering to Utopia: An Anthropology of Human Rights. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Goodale, M., and S. E. Merry, eds. 2007. The Practice of Human Rights: Tracking Law Between the Global and the Local. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hodgson, D. 1999. “Pastoralism, Patriarchy and History: Changing Gender Relations among Maasai in Tanganyika, 1890–1940.” The Journal of African History 40: 41–65. doi: 10.1017/S0021853798007397

- Hodgson, Dorothy, ed. 2000. Rethinking Pastoralism in Africa: Gender, Culture, and the Myth of the Pastoral Patriarch. Oxford: James Currey.

- Hodgson, Dorothy. 2001. Once Intrepid Warriors: Gender, Ethnicity, and the Cultural Politics of Maasai Development. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Holland, Killian. 1998. The Maasai on the Horns of a Dilemma: Development and Education. Nairobi: Gideon S. Were Press.

- Homewood, Katherine, Patti Kristjanson, and Pippa C Trench, eds. 2009. Staying Maasai? Livelihoods, Conservation and Development in East African Rangelands. New York: Springer.

- Igoe, J. 2003. “Scaling up Civil Society: Donor Money, NGOs, and the Pastoralist Land Rights Movement in Tanzania.” Development and Change 34 (5): 863–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2003.00332.x

- Jomo Kenyatta Foundation. 2003. Social Studies: Pupils’ Book for Standard one. Nairobi: Jomo Kenyatta Foundation.

- Jomo Kenyatta Foundation. 2004. New Primary English: Pupils’ Book one. Nairobi: Jomo Kenyatta Foundation.

- Jomo Kenyatta Foundation. 2005a. Social Studies: Pupils’ Book for Standard Four. Nairobi: Jomo Kenyatta Foundation.

- Jomo Kenyatta Foundation. 2005b. Primary Christian Religious Education: One in Christ: Pupils’ Book for Standard Eight. Nairobi: Jomo Kenyatta Foundation.

- Kabeer, N. 2005. “Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment: A Critical Analysis of the Third Millennium Development Goal 1.” Gender and Development 13 (1): 13–24. doi: 10.1080/13552070512331332273

- King, K. 1972. “Development and Education in the Narok District of Kenya: The Pastoral Maasai and Their Neighbours.” African Affairs 71 (285): 389–407. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a096281

- Kipuri, Naomi. 1989. “Maasai Women in Transition: Class and Gender in the Transformation of a Pastoral Society.” PhD diss., Department of Anthropology, Temple University.

- Kulet, Henry R. 1971. Is It Possible? Nairobi: Longhorn.

- Martin, B. 2011. Children at Play: Learning Gender in the Early Years. London: Trentham Books Ltd.

- Merry, S. E. 1996. “Legal Vernacularization and Ka Ho'okolokolonui Kanaka Maoli, The People's International Tribunal, Hawai'i 1993.” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 19 (1): 67–82. doi: 10.1525/plar.1996.19.1.67

- Milligan, L. 2014. “‘They Are Not Serious Like the Boys’: Gender Norms and Contradictions for Girls in Rural Kenya.” Gender and Education 26 (5): 465–476. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2014.927837

- von Mitzlaff, Ulrike. 1988. Maasai Women: Life in a Patriarchal Society. Dar Es Saalam: Tanzania Publishing House.

- Merry, S. E. 2006. “Transnational Human Rights and Local Activism: Mapping the Middle.” American Anthropologist 108 (1): 38–51.

- Moore, Henrietta L. 1988. Feminism and Anthropology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Morojele, P. 2011. What Does It Mean to Be a boy? Implications for Girls’ and Boys’ Schooling Experiences in Lesotho Rural Schools. Gender and Education 23 (6): 677–693. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2010.527828

- Mungai, Anne. 2002. Growing up in Kenya: Rural Schooling and Girls. New York: Peter Lang.

- Myers, K., and L. Raymond. 2010. Elementary School Girls and Heteronormativity: The Girl Project.” Gender & Society 24 (2): 167–188. doi: 10.1177/0891243209358579

- Paechter, C. 2007. Being Boys; Being Girls: Learning Masculinities And Femininities: Learning Masculinities and Femininities. Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Paechter, C. 2012. “Bodies, Identities and Performances: Reconfiguring the Language of Gender and Schooling.” Gender and Education 24 (2): 229–241. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2011.606210

- Paechter, C., and S. Clark. 2015. “Being ‘Nice’ or Being ‘Normal’: Girls Resisting Discourses of ‘Coolness’.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education: 1–15 doi:10.1080/01596306.2015.1061979.

- Prossomariti, V. 2013. “The Economic, Social, and Institutional Constraints on Women's Micro-enterprise Development: A Case Study of Jewelery Production among the Maasai of Kenya.” MA thesis, Utrecht University.

- Rasmussen, S. J. 2000. “Exalted Mothers: Gender, Aging & Post-childbearing Eexperience in a Tuareg Community.” In Rethinking Pastoralism in Africa: Gender, Culture, and the Myth of the Pastoral Patriarch, edited by D. Hodgson, 186–205. Oxford: James Currey.

- Renold, E. 2004. “‘Other'boys: Negotiating non-Hegemonic Masculinities in the Primary School.” Gender and Education 16 (2): 247–265. doi: 10.1080/09540250310001690609

- Renold, E. 2005. Girls, Boys, and Junior Sexualities: Exploring Children's Gender and Sexual Relations in the Primary School. Abingdon: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Republic of Kenya. 1999. Kenya Commission of Inquiry Into the Education System of Kenya: Integrated Quality Education and Training, TIQET: The Koech Report. Nairobi: Government Printer.

- Rosaldo, M. 1980. “The use and Abuse of Anthropology: Reflections on Feminism and Cross-Cultural Understanding.” Signs 5 (3): 389–417. doi: 10.1086/493727

- Rosaldo, Michelle and Louise Lamphere, eds. 1974. Women, Culture, and Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Saitoti, Tepelit ole. 1986. The Worlds of a Maasai Warrior: An Autobiography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Sena, Sarone ole. 1986. “Pastoralists and Education: School Participation and Social Change among the Maasai.” PhD diss., Department of Anthropology, McGill University.

- Skelton, C., and B. Francis. 2003. Boys and Girls in the Primary Classroom. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Switzer, H. 2013. “(Post) Feminist Development Fables: The Girl Effect and the Production of Sexual Subjects.” Feminist Theory 14 (3): 345–360. doi: 10.1177/1464700113499855

- Talle, Aud. 1988. “Women at a Loss: Changes in Maasai Pastoralism and Their Effects on Gender Relations.” PhD diss., Department of Anthropology, University of Stockholm.

- Tembon, Mercy and Lucia Fort, eds. 2008. Girls’ Education in the 21st Century: Gender Equality, Empowerment, and Economic Growth. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- UNESCO. 2010. The Central Role of Education in the Millennium Development Goals. Paris: UNESCO.

- Wilson, R. A. 2006. “Afterword to ‘Anthropology and Human Rights in a New Key': The Social Life of Human Rights.” American Anthropologist 108 (1): 77–83. doi: 10.1525/aa.2006.108.1.77