ABSTRACT

Project Re•Vision uses disability arts to disrupt stereotypical understandings of disability and difference that create barriers to healthcare. In this paper, we examine how digital stories produced through Re•Vision disrupt biopedagogies by working as body-becoming pedagogies to create non-didactic possibilities for living in/with difference. We engage in meaning making about eight stories made by women and trans people living with disabilities and differences, with our interpretations guided by the following considerations: what these stories ‘teach’ about new ways of living with disability; how these stories resist neoliberalism through their production of new possibilities for living; how digital stories wrestle with representing disability in a culture in which disabled bodies are on display or hidden away; how vulnerability and receptivity become ‘conditions of possibility’ for the embodiments represented in digital stories; and how curatorial practice allows disability-identified artists to explore possibilities of ‘looking back’ at ableist gazes.

Introduction

Art is how the body senses most directly, with, ironically, the least representational mediation, for art is of the body, for it is only art that draws the body into sensations never experienced before, perhaps not capable of being experienced in any other way.

(Grosz Citation2008, 73)

The theoretical and artistic work we examine in this paper is derived from Project Re•Vision, an arts-based research project that puts on digital storytelling and drama workshops in which women and trans* people living with disabilities and healthcare providers create new and multiple representations of embodied difference (Rice et al. Citation2015). Our project explores the possibilities of the creation and curation of disability art to disrupt stereotypical understandings that create barriers to healthcare and inclusion in society. In Re•Vision’s first two years, 2012–2014, we ran 14 digital storytelling workshops; of which three allowed all researchers and students involved to make their own digital stories, and two enabled some of us to receive facilitator training. Our workshops enable participants to create digital stories, which are two to three minute-long videos pairing audio recordings of personal narratives with visuals (photographs, videos, and artwork). The aim is to create spaces where people unpack and ‘talk back’ to received representations and make new meanings. To date, we have generated an archive of over 200 digital stories.

This research methodology reflects our belief that art can be pedagogical without being didactic or teleologically oriented. Extending from that belief, our paper is animated by a central question: How can art teach? Specifically, how does the art produced within Re•Vision workshops teach? We are confident that art can teach; our research is based on the belief that art made by differently embodied people provokes healthcare providers to understand disability in new and different ways. In this paper, we present two sets of curated digital stories produced through Re•Vision workshops, and rather than asking what this work teaches, we think through the complexities of how this work might teach in non-didactic ways to indeterminate ends. Our desired pedagogical audience spans inside and outside the classroom, as we imagine these artworks to promote ‘becoming pedagogies’ that change the way we understand embodied difference. These artworks teach in a way that is not corrective, replacing ‘bad’ representations with ‘good’ ones, but expansive, offering a multiplicity of representations. For the becoming possibilities of these stories, we include ourselves, a group of cisgender women and genderqueer femmes with varied personal experiences and histories of living with mind/body difference.

We begin by describing our self-reflexive and community-oriented approach to interpreting people’s stories, which we understand to be contextual, collaborative, and essential to our curatorial practice. We reflect on biopedagogies – instructions for living ubiquitous in our individualising, biomedicalising, homogenising culture (Rice Citation2014). We follow by thinking through how artistic works, specifically Re•Vision films, are pedagogical in ways consistent with body-becoming orientations that offer not normalising and moralising instructions for life, nor a fixed understanding of what ‘being human’ is, but rather, open up new, non-didactic possibilities for living in and with difference. We talk about the experience of being in our workshops as artist-storytellers and reflect on how creating new representations enabled us to not only ‘talk back’ to dominant representations but to deepen our own understandings. Analysing stories created in these workshops, we assert that they engender post-humanistic becoming pedagogies, productively disrupting the idea of the human as autonomous, ‘able’ and ‘useful’ (under neoliberalism), and instead expanding possibilities for what a body can do and become. Finally, we frame the work of Re•Vision as an unfolding of new disability ontologies in/through art. Returning to the questions of how art teaches in ways that resist neoliberal, utilitarian understandings and to the broader relationships between pedagogy and research, we think through how the stories might affect audiences, while resisting the demand of art and artists that they must be useful according to neoliberal logics (Dávila Citation2012).

Disability digital storytelling and curatorial practice

Digital storytelling is a multimedia narrative form that developed in the 1990s as a digital adaption of the live theatre and radio genres of auto/biographical monologue (Benmayor Citation2008). It has since evolved into an arts-based research and pedagogical tool for enabling critical and creative theorising and storytelling through self-representation. What may distinguish digital storytelling from other arts-based methods is that it allows participants to voice unspoken – or perhaps unheard or unrecognised – experiences and to re-engage with those experiences, writing narrative, creating images, and capturing sound to clarify and layer their intended meanings. In this iterative, generative process, storytellers ‘voice another storyline’ (Golden Citation1996, 330), constructing preferred meanings of experiences, coming out from under existing stories by speaking back to culturally dominant images/narratives (Rice and Chandler Citation2016). In our accelerated, truncated, and neo-liberalised culture where many people are time-starved, we see the genre as enabling an economy of expression through the layering of meanings using narrative, image, and sound, resulting in an art form that can convey depth within a highly compressed timeframe. The distillation and densification of experience that this genre allows has emerged as particularly powerful both for Re•Vision filmmakers and audience members who have responded to the work.

We situate Re•Vision work in the methodological traditions of critical arts-based (Conquergood Citation2002) and participatory action research (Kemmis, McTaggart, and Nixon Citation2014) and consider these traditions as complementary insofar as they each endorse postmodern, participatory, political, and process-oriented principles/approaches. Although digital storytelling methods have been employed in various research projects and for educational purposes, we think that the Re•Vision methodology is distinctive for the way it brings together disability-identified artists/activists with researchers, health providers and disabled people (not mutually exclusive groups) to speak back to tropic representations of disability by re-storying embodied difference. As such, our project features an original curriculum delivered in a four- or five-day workshop series that includes the following elements: an interactive presentation on the existing representational field and how disability-identified artists/activists have intervened in it; experiential tutorials on storytelling, photographic literacy, image composition, and sound, image and video editing that are geared to participants’ skill levels; open studio with a one-to-one ratio of artists/technical experts and non-artists who work collaboratively to generate the work; and screening sessions where filmmakers present and interpretive communities reflect on the work shared. This methodology is distinctive among digital storytelling research projects in the ways it brings together critical social science theory and research concerns with a genuine engagement with cultural theory and the values and approaches of the humanities.

Our methodology also draws from and contributes to a set of emergent approaches in the arts referred to as disability arts practice (Cameron Citation2009) and understands such art not only as a tool for social change, but as of inherent aesthetic interest and value (Raphael Citation2013). We are also guided in our work by activist art traditions, which Marit Dewhurst describes as those involving art created ‘with an expressed intention to challenge and change conditions of inequality or injustice’ (Citation2010, 10). In our work we draw from aesthetic theory and engage intensively with disability-identified artists, making our processes and outputs more than manifestations of creativity, or a means of therapy – as disability art has often been conceptualised – but disability artistic and activist processes and ‘disart’ creations in themselves.

As with workshop processes, Re•Vision’s analytic processes are highly collaborative, countering traditional knowledge production processes by privileging the filmmakers’ own reflections on, and sometimes theorising of, their work. Through dialogue, these reflections and analyses are augmented with interpretations offered by other storytellers, academics, and audience members whose insights layer and nuance those initially put on offer. We also intentionally frame the stories created, providing interpretation and contextualisation of each, not to ignore curatorial tradition but to deliver on an ethic of disability curatorial practice. The traditionalist streak in us wants the art to be made meaningful on its own: when we create art, we commit to releasing it into the world, freed from our intention or interpretation as artists, with a desire to spark or continue a dialogue. However, a disability art and curatorial ethic recognises that when we who embody difference make artwork that represents ourselves, we release these re/images into a culture rich with representations of difference. This is because disability art that attempts to re-present, refigure and reinterpret embodied difference contends with the ableist logics through which these re/images are read; contends with an art history full of tropic representations; and contends with an ongoing history of being on display in freak shows, examining rooms and on reality TV (Garland-Thomson Citation2009). Further, this contention is risky – losing re/images of difference is risky. Mediating this risk requires us to intentionally disrupt traditional curatorial practices by offering a framing of the artwork that has been generated through this research, some of which we embed in this paper.

Pushing against humanist biopedagogies

In order to consider the pedagogical possibilities of digital stories produced through Re•Vision, we define the relationship of this project to the concept of pedagogy. Our work is informed by Basil Bernstein’s revelation that we inhabit a ‘totally pedagogised society’ (Citation2001, 365) in which individuals are shaped as hyperflexible learners, capable of continuous re-formation and adaptation to the sped-up and intensified precariousness of life under neoliberal capitalism (Gewirtz Citation2008). The totally pedagogised society’s ‘systems of control from instruction’ (MacNeill and Rail Citation2010, 179) mediate all aspects of contemporary social life. According to Singh (Citation2015), the concept of the totally pedagogised society is interpreted as ‘dystopian’ by many critical theorists (364). Singh proposes an alternative reading, wherein the ‘socially empty’ self (Bernstein Citation2001, 366) Bernstein describes as resulting from processes of pedagogisation does ‘not simply [internalise] the message of neoliberal economic performativity’ (Singh Citation2015, 375), but may instead become ‘an ambivalent, uncertain self, torn between the desire for more knowledge and the paradoxical emptiness and uncertainty that such longing brings’ (378). Singh’s analysis of Bernstein’s comments concerning the post-humanist transformational potential of ‘human and non-human interaction’ (375) through technology is particularly relevant to Re•Vision’s work in developing ‘becoming pedagogies’, that make interventions into fields determined by dominant pedagogies.

As Elizabeth Ellsworth (Citation1997) writes, pedagogy is a ‘social relationship [that] is very close in. It gets right in there in your brain, your body, your heart, your sense of self, of the world, of others, and of possibilities and impossibilities in all those realms’ (6; quoted in Leahy Citation2009, 177). In the current context of individual responsibilisation and retrenchment, pedagogies concerning bodies are pervasive. These have been conceptualised in the critical literature as ‘biopedagogies’. By biopedagogies, we mean the loose collection of moralised information, advice, and instruction about bodies, minds, and health that works to control people by using praise and shame alongside ‘expert knowledge’ to urge conformity to physical and mental norms (Rice Citation2014, Citation2015). These ‘assemblages’, as Leahy (Citation2009, 177) describes them, of instructions and directions about how to live, how to be embodied, and what to do to be ‘healthy’ and happy and avoid ‘risk’, are transmitted in formal educational contexts, healthcare institutions, and everyday interactions (Harwood Citation2009).

Biopedagogies, derived from the concept of ‘biopower’, emerge in organised systems of modern power (Foucault Citation1979). In its original conceptualisation in the work of Michel Foucault, biopower is enacted in state arrangements to discipline a citizenry to the point of docility and economic efficiency. Normative rules found in expert advice, public health standards, and interpersonal judgement direct persons into being a specific sort of citizen, one whose body is through repeated disciplinary practices divested of its power (Foucault Citation1979). According to Debra Gimlin, ‘cultural rules are not only revealed through the body; they also shape the way the body performs and appears’ (Citation2002, 3), meaning, upon our bodies rules of governance are inscribed and through our bodies those rules are enacted.

Negotiations with biopedagogical scripts that create/constrain bodies have bearing on identities like gender and disability insofar as these are understood as constructed, performative artefacts. For Judith Butler, ‘performativity’, a citational practice ‘by which discourse produces the effects that it names’ (Citation2014, 16), explains how gender is a doing, enacted through a set of iterative and expected activities. Each iteration sediments a particular gender construct, and within a hegemonic frame some genders available for enactment are associated with the abject, meaning that through the process of being rendered legible these embodiments are marked as wrong. It is here that feminist and disability theory find solidarity, for the idea of the abject body – found lacking or excessive compared to idealised imaginings of embodiment – applies as readily to disability as it does to gender. Perhaps more than solidarity, a merging of the theories has for Hall (Citation2011) the power to ‘reimagin[e] gender’ (1), for how gender is rehearsed, and how that rehearsal is theorised – in relation to sexuality, medicalisation, and social status – is contingent on connections and collisions with disability. Thus, feminist disability analysis is not merely additive but instead posits that re-theorising disability necessarily implicates gender and transforms gender’s meanings and markers.

In our image-oriented culture, visual representations of bodily differences often function as biopedagogies. This is because representations tend to carry (often implicit) instructions for how we should live in our bodies and to establish a set of mind/body norms to which we all must conform. For example, the familiar stories about disability (coded in ferocious monsters, Christmas miracles, cautionary tales, and operatic tragedies) limit our understandings by fitting mind/body differences into tidy, tiny boxes. Through representations functioning as biopedagogies, we are taught that disabled bodies are frightening/fascinating objects to stare at. Acts of staring at bodies on display are also pedagogical: they teach us what kinds of bodies/behaviours are ‘abnormal’. The non-conforming body/mind itself thus serves as a biopedagogy as it gives us a sense of what a normal embodiment is and can do. While differences deemed correctable (for instance fatness, or learning difficultiesFootnote2 such as dyslexia) are most often targeted for normalisation, biopedagogies may apply other kinds of instructions to those currently categorised as unchangeable and intractable (such as physical impairments like blindness and spinal cord injury, and certain mental health diagnoses). These types of instructions set different, lower standards for the body or mind marked as deficient in order to embed in that embodiment responsibility for ‘failure’ so as to maintain ableist standards of normalcy (van Amsterdam et al. Citation2012; Chandler and Rice Citation2013). That the cultural imagination for disability is found so wanting leaves us at Re•Vision hungry for the experiences that are not being storied, a hunger which set the impetus for Author A’s creation of this research project. We believe that storying untold stories is part of the work of artists.

Post-humanistic becoming pedagogies

As a community of artists, researchers, and educators engaged in creating and interpreting art outputs on this project, we have begun to think about biopedagogies in the context of feminist scholar Rosi Braidotti’s work on the post-human. Braidotti (Citation2013) suggests that ‘humanity is very much a male of the species: it is a he. Moreover, he is white, European, handsome and able-bodied … an ideal of bodily perfection’ (13), who ‘speak[s] a standard language, [and is] heterosexually inscribed in a reproductive unit and a full citizen of a recognised polity’ (65), as well as ‘a rational animal endowed with language’ (141). According to Goodley and Runswick-Cole (Citation2014), this vision of the human has at its core Eurocentric and imperialist tendencies, ‘meaning that many of those outside of Europe (including in the colonies) become known as less than human or inhuman’ (2). This framing of the human ensures that some of us are more human than others, and that many are excluded from the category. Fitting with Braidotti’s critique of the (humanist) human, we suggest that biopedagogies’ resolutely didactic scripts serve to produce the archetypal (masculine, cisgender, white, non-disabled, middle class, straight) citizen and autonomous human subject under neoliberal capitalism. Those considered other to this limited conceptualisation of humanity are positioned to fail, never fully enacting the bodily selves of biopedagogical scripts.

Rather than teaching people to adopt normative understandings of the human or to accept that those of us with body/mind differences must live marginal lives, how do we create the cultural and material conditions that will enable us to imagine other, more expansive possibilities for our embodiments, possibilities that anticipate difference and frame it as something other than failure? In contrast to biopedagogies, ‘becoming pedagogies’ (Rice Citation2014) would move away from practices of enforcing norms towards more creative endeavours of exploring abilities and possibilities unique to different embodiments. The ‘becoming’ of this sort of pedagogy derives from body-becoming theory (Rice Citation2014, 277), which is attenuated to the emergent and agential properties that keep embodied subjectivities from being fixed, contained, or tamed within discursive regulatory frames. Far from docile, these subjectivities are rooted in embodiments that are ever materialising in provisional configurations that interact and are entwined with, but are also defiant of thematic structure (Barad Citation2007; Grosz Citation2010).

Subjectivities who through their becomings are defiant of expectation can be found in feminist theory. For example, Ahmed (Citation2010) asks us to consider (anti-feminist) acts of naming in response to noncompliant women such as the feminist ‘kill-joy’ who offends for being ‘an affect alien: she might even kill joy because she refuses to share an orientation towards certain things as being good’ (39). So too with the angry black woman trope taken up by Lorde (Citation1984) and hooks (Citation2000), Ahmed argues that those who oppose hegemonic constructions of gender and race may be thought catalysts of displeasure, when their defiance works to identify and dismantle discursive and material violence. To embrace the kill-joy is to position one’s subject formation against biopedagogic frames. Along similar lines, Mintz (Citation2011) suggests that narratives written by disabled women carry with them ‘an act of defiant self-recreation’ (72) to the extent that these sorts of narratives conjure, but in so doing disrupt, regulatory representations of disabled, gendered subjectivity. Self-recreation is at once agential, resistant, and new.

How becoming pedagogies might guide representations of and responses to disability is an open question, but they invite us to think about the discursive and material effects of meanings we give to mental/physical differences. They ask us to consider how much agency we lose by imposing certain expectations onto body/minds and how much possibility we miss in attempting to regulate human diversity. We see arts-based approaches produced by Re•Vision in spaces of alterity as becoming pedagogies, alternatives to biopedagogies that enable the doing and undoing of bodily subjectivities. Rather than being outcomes- or ideals-driven, becoming pedagogies are presence- and process-oriented, and interested in improvising the properties and potentialities of all embodiments.

Digital storytelling: facilitating the becoming of post-humanist subjectivities

We frame our first set of digital stories using Braidotti’s characterisation of the post-human condition, which ‘urges us to think critically and creatively about who and what we are actually in the process of becoming’ (Citation2013, 12). Braidotti’s work conceptualises a self in flux, positioned at the limin between nature and nurture, no longer bound by skin but extending into techno-cultural relations. We suggest that Re•Vision’s technological tools produce the post-human condition, by providing the means by which filmmakers might explore, develop and come to terms with their embodied subjectivities. The subjectivities discovered or created are inextricably tied to the digital media that makes them possible. Thus, even through the process of filmmaking, participants are enacting a self in-becoming.

One illustration of how artist-storytellers confront and represent their becoming selves through digital media is found in a story made by genderqueer disabled artist, filmmaker and Re•Vision facilitator, jes sachse.Footnote3 In their piece Body Language (to screen this video go to http://projectrevision.ca/videos/ and following the prompt, type in the password ‘unruly’), sachse explores the complexities of ‘looking relations’ for people with disabilities in a representational history of disabled people that can largely be characterised as one of being put on display or sequestered away.

In this video, we see many different photographs of sachse, from childhood to adulthood, laughing with friends, creating in the art studio, and standing by train tracks. Towards the end of the video, we see photographs of sachse, nude, stretching their limbs (), and standing in front of sun-filled windows. By daring viewers to look at their body and imagine how it feels to look like them, sachse subverts the typically voyeuristic, dominating practices of looking that structure encounters with difference – practices that Garland-Thomson (Citation2009) unpacks in relation to both gender and disability – and provokes us to consider the complex ways that intense looking can remake viewers’ perceptions. Insofar as sachse created their video out of a desire to discover what everyone is staring at when they stare at sachse, their video is less about us, the audience, than it is about them, the artist, exploring their unique embodiment. Through their interrogation of the mirror’s image, which both invites us as viewers to look and incites us to question our urge to stare, sachse challenges audiences to acknowledge our responses to their differences (sex, bodily difference) and our relationships with our own. Through this refraction, they refocus our collective gaze onto societal views of difference and illuminate the myriad ways we may share the experience of what it is to be vulnerable, flawed, and in other ways embodying of ‘difference’, especially in relation to the culturally normalised masculinist, straight, non-disabled, and neo-liberalised mode of embodiment – independent, self-contained and under control (Shildrick Citation1997). Sachse created this video in 2007, towards the beginning of their artistic practice, in response to the dearth of representations of bodily difference. Sachse has continued to develop their artistic practice, and we feature a more recent video by the artist later in this article to illustrate the trajectory of this aspect of their work.

Figure 1. Still frame showing a black and white photograph of sachse lying on their back with their legs raised against a backdrop. A caption reads ‘Hard, long, frame after frame’. From Body Language by jes sachse.Footnote4

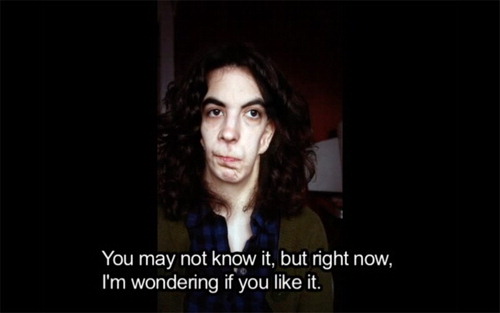

The second digital story we discuss was created by Lindsay Fisher, a visual artist and Re•Vision workshop storyteller-facilitator (to screen her video go to http://projectrevision.ca/videos/, and following the prompt, type in the password ‘unruly’). In First Impressions, Fisher does more than grant people permission to look intently at her. In her search to discover what onlookers see when fixing their eyes on her, she asks audiences to look beyond first impressions to find value in difference. This video features hundreds of photographs, in which Fisher is making different facial expressions that accentuate her difference, flashing rapidly on the screen ().

Figure 2. Still frame showing a colour photograph of Fisher looking past the camera and pursing her lips. A caption reads, ‘You may not know it, but right now, I’m wondering if you like it’. From First Impressions by Lindsay Fisher.

Fisher describes beginning her story-making process by recollecting moments in her life when she was most of aware of being different. While she aimed to tell a counter-story that disrupted the typical disability pity narrative, she also wanted to discover something about her difference that would surprise her when she saw it – something that she, herself, did not know was there. What emerges from her technique of taking and editing into a short video over 300 photographs of herself ‘making faces’ is a provocative exploration of a complex embodiment from inside her skin – fluid, dynamic, continuously shifting – which she contrasts with the view from outside it, the ways that responses to difference are thought to be already socially ‘made’. Layering and opening from this insight, she offers us a delightful meditation on the pleasures and sensualities of her embodied experiences. By subverting the usual ways that gendered bodily difference is either de-sexualised or fetishised in normative image culture, she discovers and claims her facial difference as a site of sensuality that is charged with erotic possibility.

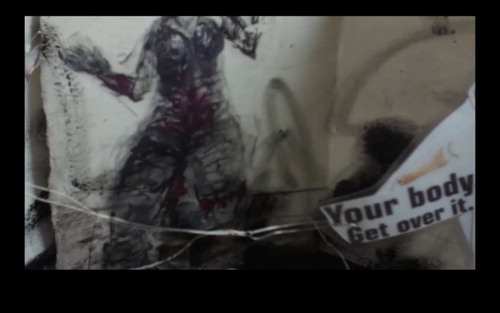

The third story in this set, slide/cascade, was created by disability artist Elaine Stewart (to screen this video go to http://projectrevision.ca/videos/, and following the prompt, type in the password ‘unruly’). In this piece, Stewart pairs her poetry with her art, and through this pairing, we receive a story that could, perhaps, only emerge through a digital storytelling method. Historian Caroline Walker Bynum asserts, ‘Shape or body is crucial, not incidental, to a story. It carries story: it makes story visible; in a sense it is story’ (quoted in Garland-Thomson Citation2007, 113–114). ‘Situations of ecstatic strife’, the first line of Stewart’s video, is accompanied by a figure, rendered out of charcoal, seated in a wheelchair. This figure is placed beside the words, ‘Your body. Get over it’ (). The figure’s placement beside these words could evoke the feeling of being placed in the midst of a cacophony of messages that tell us disability is a problem to be overcome, we should desire to roll away from disability, get over our bodies, in order to be freed from the cultural scripts of lack and deficiency that disability attaches to our bodies.

Figure 3. Still frame depicting a drawing of a figure seated in a wheelchair placed beside the words, ‘Your body. Get over it’. From slide/cascade by Elaine Stewart.

As disability studies scholars, we often think and teach about how problematic representations of disability inform cultural understandings and, thus, experiences of disability, but in the opening moment of Stewart’s video, we can feel theory on our bodies, akin to what Benmayor (Citation2008) describes as ‘theoriz[ing] from the flesh’ (198). Stewart’s video might permit us to feel ecstasy and strife in our bodies at the same time. It could even permit us to feel ecstasy in the strife of the materiality of our bodies. This opening scene teaches something about our bodies and how they could become. When we think about the cyclical relationship of how representations inform understandings of particular kinds of people, and how such understandings inform how we treat people, we see the power of the arts in effecting change. Creating new representations of gendered bodily difference can transform understanding of difference, which will change how people are treated. And so, it may be straightforward to create a representation of disability that effectively contradicts a dominant representation (i.e. disability is a represented as a site of pain, so we render disability as a site of pleasure), but the task is more complicated when an experience of disability matches its dominant representation. Stewart’s video offers a nuanced, possibly risky story of disability representing it as ‘strife’. However, through Stewart’s rendering of her strife as ecstatic, we arrive at a new understanding of disability that does not overwrite the materiality of the body.

We end this first set of stories with Me & You, a video by disability studies scholar and Re•Vision participant Kirsty Liddiard. Telling her story for the first time, Liddiard reflects upon the fears, pleasures, vulnerabilities, and sensualities which encompass her disability experience. Identifying as a proud disabled woman, she also complicates the counter-story of disability pride found in disability rights movements. In her video, Liddiard applies affirmative politics which ‘combine critique with creativity in the pursuit of alternative visions and subjects’ (Braidotti Citation2013, 54) in order to re-contextualise her self-perceived vulnerability, frailty and future. She juxtaposes rapid, flickering imagery of her happiness, her loved ones and the ‘adventures’ upon which her body has taken her () with more serene monochromatic images during which the video slows down to emphasise the uncertainty and multiplicity of the identities, embodiments and labours she lives.

Figure 4. Still frame depicting a colour photograph of a calm body of water from the rocky shore to the horizon, under a blue sky with a few clouds. A caption reads ‘But we’re in this together, me and you’, from Me & You by Kirsty Liddiard.

Rather than ‘speaking back’ (as we often say in Re•Vision), she was ‘speaking to’ herself in ways that did not seek to simplify the intricacies of her being. She says of her story:

As my story implies, I am an activist who sometimes feels shamed by the oppressions I stand against. I am an academic who critiques the Academy. I am a disabled woman who worries about motherhood even though I am knowledgeable of the oppressive intersections of ableism and parenting. I am a disabled person who experiences pain and (sometimes) suffering, yet I love my body and the lessons it teaches me. I am a partner who fears future impairment even though I have a life partner who never denies my disabled self, but loves me for it. I am a lover who worries if she’s ‘good enough,’ even though I write about the sexual possibilities of disability. Since the video was made, I’ve become a permanent family foster carer – another liminal space, whereby I have committed my life to bringing up a child, without becoming/being a parent. Making my story didn’t remove these contradictions, but enabled me to understand them as part of my body, self, and life. The boundaries of lover, partner, self, (future) mother, carer, aunt, scholar, activist, daughter, disabled woman – I have come to realise – are never tidy or discrete but fractured, duplicitous, unpredictable, paradoxical and fleshy. Creating a digital story has enabled, I would argue, an appreciation and even celebration of these contradictions: it has revealed, for me, what I imagine Braidotti’s notion of becoming-posthuman to be. (Liddiard Citation2015)

Digital storytelling in community: becoming together

Re•Vision engages a methodology that is arts-informed, recognising that embodied arts-informed research practices need to be ‘active, interpretive, and relational [such that] aesthetic processes have a corporeality that produces and carries meaning’ (Halifax Citation2004, 176). We work with such a methodology because we find affective work can reach and convey difficult knowledges and truths that do not at all or at least easily fit into linguistic and conceptual confines. The implication, however, is that the open-ended nature of artistic interpretation – the ways in which art moves people, invoking sensation and memory alongside thought – means it is difficult to fix our analysis. The intentions motivating and the context surrounding each story cannot fully frame the meaning that story contains. Not that we want it to, but this means that just as the author is ‘born simultaneously with [her] text’ (Barthes Citation1977, 4), and just as the filmmaker’s subjectivity is developed within the process and medium of filmmaking, so too are the digital stories reborn into each endeavour to disseminate, for they become something different for every audience that receives them.

In Re•Vision workshops, we work to create the conditions for postconventional possibilities: we purposely set up our workshops to be spaces of radical relationality, community, accessibility and accountability, and to be intimate, nourishing and safe(r) spaces to tell our stories. With a dialogical emphasis and polyvocal approach, workshops offer rich spaces in which storytellers’ stories are listened to in new ways. Such spaces both require and create community in vital ways. This coming together – or becoming-together – serves to embody and enrich individual stories since according to Benmayor (Citation2008), ‘without … community, [stories] would not be as deep and powerful as they are’ (198).

We welcome in filmmakers who are routinely culturally disavowed, those offered only a subhuman status in the context of the (humanist) human: women, disabled, D/deaf, and Mad people, people with addictions, Fat people, queer, genderqueer, and trans* people, racialised people and Indigenous peoples. The workshop serves as a space which (inadvertently) enables the post-human subject, who for Braidotti (Citation2013), exists

within an eco-philosophy of multiple belongings, as a relational subject constituted in and by multiplicity, that is to say a subject that works across differences and is also internally differentiated, but still grounded and accountable. Posthuman subjectivity expresses an embodied and embedded and hence partial form of accountability, based on a strong sense of collectivity, relationality, and hence community building. (49)

Our second set of digital stories animate themes of ‘becoming’ and ‘post-humanism’ in disability community. In Leaving Eustachian, artist jes sachse reveals the possibilities that arise from hearing impairment, which enables them to navigate the world differently by turning on and off the surrounding world (to screen this video go to http://projectrevision.ca/videos/, following the prompt, type in the password ‘unruly’). We feature sachse’s second video to demonstrate how people live with multiple experiences of disability, and thus stories, within those experiences.

Offering an intricate, intimate soundscape of the subway, sachse playfully contests hearing as an able-bodied privilege. The harshness of subway sound – the roar of the entering/exiting train, the aimless footsteps, the chatter, shouting, and laughing () – is discarded by sachse, as they provide the audience with an aural engagement that enables a questioning of the idea of hearing as privilege. Thinking in provocative ways about the relationship between body and world, sachse reveals the ways that they ‘become’ in interactions with their surrounding environments.

Figure 5. A still frame showing an empty subway station platform as a train leaves the station, with a caption reading ‘[Voices, laughter]’ appearing at the bottom of the frame. From Leaving Eustachian by jes sachse.

![Figure 5. A still frame showing an empty subway station platform as a train leaves the station, with a caption reading ‘[Voices, laughter]’ appearing at the bottom of the frame. From Leaving Eustachian by jes sachse.](/cms/asset/c6274b86-f576-4505-affa-cace278c1f19/cgee_a_1247947_f0005_c.jpg)

To explore how digital stories created in Re•Vision workshops can open up new ways of perceiving disability with indeterminate ends, we feature video by Jan Derbyshire (to screen this video go to http://projectrevision.ca/videos/, following the prompt, type in the password ‘unruly’). Derbyshire is a disability artist who identifies as having lived experience with hearing voices. Her video, entitled Mrs Green, features a close-up image of Derbyshire playing with, tapping, and shaking a set of old pill bottles that had once contained prescriptions for a Mrs Green, but became a thrift store find for Derbyshire. Derbyshire’s video presents new possibilities for knowing difference, and ways of thinking that could help make the world more interesting and beautiful. Mrs Green’s story is revealed to Derbyshire through her ability to hear stories from objects in her environment, and she shares it with the audience as she shows that the prescription bottles have been repurposed to hold colourful sequins. Multiple possibilities for these objects and their meaning are explored, with the bottles becoming impromptu instruments as Derbyshire shakes them in time with a song she sings (). When the lyrics ask, ‘Doctor, is there something I can take?/Doctor, to relieve the pain?’ the glittering contents of the pill bottles shake out a response, a radical, yet playful, intervention in to the medicalisation of difference and distress.

Figure 6. Still frame of Derbyshire shaking a sequin-filled pill bottle, with a caption reading ‘(Shake, shake.)’ From Mrs. Green by Jan Derbyshire.

Through her video, Derbyshire presents us with another way of orienting to hearing voices. In this alterity, experiencing perceptual differences are not met with responses aimed at cure, containment, or control as dominant narratives claim are desirable and necessary. Instead, Derbyshire suggests that when we allow ourselves to live with difference and attend to what life with difference teaches, we might arrive at a ‘more beautiful place’ (Chandler and Rice Citation2013, 14).

In the next story we discuss, scholar Jen Rinaldi gives us an insider account of practices of self-starvation, describing the inner biopedagogical voices that fuel them as her Litany of White Noise, which is also her video’s title (to screen this video go to http://projectrevision.ca/videos/, and following the prompt, type in the password ‘unruly’). Because of its emphasis on the subversive force of an inner voice, this film is organised around its script, such that the visuals employed – floating orbs of light that swell, contract, and alternate colours – have a synaesthetic effect ().

Figure 7. Still frame of multi-coloured bursts of light against a black background, with a caption reading ‘And yet, buried under my clothing’, describing inner biopedagogies used to maintain self-starvation. From Litany of White Noise by Jen Rinaldi.

Rinaldi ran an audio synthesiser and held a camera up to a desktop screen, a technique that introduces an unsteady hand to the production, and in fleeting moments catches her reflection staring back at her audience. These imperfections presence the filmmaker without unveiling her body, a visual that might have invited objectification. Rather than satisfying the audience’s hunger to see her abject or normalised body, Rinaldi resists becoming the object of our gaze, telescoping us back into her embodied experience by choosing to represent her story using a rhythmic dance of colours choreographed by her voice. In so doing she maintains a subject position in the storytelling, avoiding placement in traditional psychiatric recovery narratives told by someone other than the person under diagnosis and resisting conventional eating disorder recovery stories that typically feature the ‘feminine grotesque hysterical body’ (Lupton Citation1996, 110). A counter-narrative such as Rinaldi’s is not as easy to pin down to a particular imaged being, where body markers might confirm whether she is fat or thin, healthy or sick. So her film animates a dilemma with which Saukko (Citation2008) wrestles: ‘Maybe anorexics need an explanation in order to recover – a healing story. Maybe not. A story to satisfy our vigorous craving for final explanations’ (29). The rhythm of Rinaldi’s digital narrative indicates there may be little by way of finality in recovery, no end to the interiorised experience of difference, no simple overcoming trajectory, and no single, fully satisfying account to encompass a person’s becomings.

The final video discussed is created by Potowatami and Lenape Aboriginal artist Vanessa Dion Fletcher (to screen this video go to http://projectrevision.ca/videos/, and following the prompt, type in the password ‘unruly’). In WORDS, Dion Fletcher uses homophones to juxtapose her first-person experiences of a learning difficulty with the objectifying language of diagnostic tests. This narrative features a blank piece of white paper on which the viewer sees a hand write out words, homophones, and sentences from a psychologist’s diagnostic report ().

Figure 8. Still frame showing a hand writing out words from a diagnostic report from WORDS by Vanessa Dion Fletcher. A caption reads ‘relitive strenths [sic] in flued information, spatial resoning’.

![Figure 8. Still frame showing a hand writing out words from a diagnostic report from WORDS by Vanessa Dion Fletcher. A caption reads ‘relitive strenths [sic] in flued information, spatial resoning’.](/cms/asset/2e3ff922-32c2-4af7-bdcd-8f542e23fa5f/cgee_a_1247947_f0008_c.jpg)

The soundtrack consists of Fletcher’s playing with different meanings of homophones. Her sounding out of consonants and vowels of written language brings us into the experience of being a child with a learning difficulty struggling to decode and sound text. Fletcher describes herself as spelling in non-normative ways due to differences in storing and retrieving written information. Using words that sound alike but which have different spellings and meanings, she opens audiences to consider how her own unique ways of spelling, typically read as mistakes, can instead be understood as her creation of new meaning through written language. She asks us to consider how the language of deficiency limits children but how the magic of words also might open up other possibilities for being and becoming. Her piece resonates with recent scholarly work on the over-representation of racialised and Indigenous students among those diagnosed with a learning difficulty/disability (Harwood and Allan Citation2014), and can be understood as an act of resistance against the objectifying and possibility-negating construction of students labelled as having learning difficulties as deficient within Eurocentric education’s limited paradigm (Urrieta Jr. Citation2015). Her creative response exemplifies the unpredictable possibilities that open when we welcome disability in.

Unfolding new disability ontologies in/through art

What can thinking outside of/past the (humanist) human offer arts-informed methodologies? How does Re•Vision, through its becoming pedagogies, foster the post-human? What are the required relationships between research and pedagogy to meet this end? The work of Gilles Deleuze, who wrote extensively on the power of art to dislodge sensation, perception and affect from their expected associations (in this case of gender and disability with incapacity, abjection, the subhuman), offers rich insight into the ways that art might disrupt our pre-reflective, gut-level reactions and provoke new visceral responses to things (Colebrook Citation2006). In her reading of Deleuze, Grosz (Citation2008) reflects on the power of art to create and proliferate unexpected perceptions by magnifying or intensifying previously unrecognised properties and qualities of phenomena. She writes,

Art is not frivolous, an indulgence or luxury, an embellishment of what is most central: it is the most vital and direct form of impact on and through the body, the generation of vibratory waves, rhythms that traverse the body and make of the body a link with forces it cannot otherwise perceive and act upon. (59)

Grosz suggests that artistic representations operate at a different register from scientific ones by opening up emergent, unpredictable alternatives for sensing and knowing difference. Thinking with Grosz and Deleuze, Re•Vision’s interventions may function pre-reflectively as becoming pedagogies that offer non-didactic, indeterminate and post-human possibilities for living in/with differences. While intensifying qualities of disability (asymmetry, leakiness, imperfection) through art and aesthetics may bring something new into the world, this ushering in of the unpredictable and non-prescriptive is risky – what it generates cannot be foreseen. Art interventions as becoming pedagogies are necessarily non-didactic and non-normalising, but they are still instructive and productive insofar as they produce new possibilities for living. By reflecting on the work of Re•Vision, we hope to make space for pedagogies that expand openings for improvisation, creativity, sensory pain, pleasure, and the yet-to-be recognised range of affects, precepts, and experiences in and of difference, and hence, for remaking the once-abject into radically becoming subjectivities.

Our project raises an important methodological question about the relationship between pedagogy and research and what Re•Vision’s art explorations might offer to both. We see our research as inherently pedagogical, both intentionally and unintentionally. Our ‘outputs’ are pedagogical in that they are intended to share with audiences of policy makers, practitioners and others, following the belief that art can teach in non-didactic ways to indeterminate ends. Audience engagement is often profound, as the emotionality of the films blurs the boundaries between self and other, while the specificity of the stories told registers each storyteller as a self who can only ever be partially known (thus keeping the category of the human open). Audiences are drawn in and, as they have told us, locate themselves in others’ stories even as they think about their own positionality in relation to and implicated in the conditions of those others. This ‘imaginal knowing’ (Leonard and Willis Citation2008, 1) ‘moves the heart, holds the imagination, finds the fit between self-stories, public myths, and the content of cultural knowledge’. Imaginal knowing is not fantasy; rather it evokes the deeply personal way that humans envisage and come to know their worlds. In the liminal space between representation and reality, new understandings of disability are produced, learned and taught. In addition, since the process of creating a self-reflexive artwork is often one of self-discovery, new meanings of the self and flesh emerge as artist-storytellers interrogate how to live with/in disability and marginality. Along with alternative views of self that come into play, storytellers have opportunities to re-learn (or unlearn) negative ontologies of disability. That their self-learnings are inextricably connected to the teachings they offer audiences makes it extraordinarily difficult, if not impossible, to fully disentangle research from pedagogical processes in our work. In the arts-based work described here, pedagogies necessarily overlap and enmesh with research processes, and carry the potential to instantiate post-human becomings for artists and audiences alike.

This brings us to our animating question which is, given that art teaches, but does so on a different register than a scientific one, how might we conceive of the pedagogical possibilities of these videos as in keeping with a body-becoming, post-humanist convention? We believe that Re•Vision workshops, the videos/art that emanate from them, and the ways in which these are curated, facilitate an acceptance or emergence of post-human subjectivities. Our readings of the videos made through Re•Vision suggest that teaching new ways of living with disability through disability and digital arts practices can offer filmmakers and audiences multiplicitous and emancipatory possibilities for living. At the same time, the stories created, through wrestling with the tension of representing disability in a culture where bodies of difference are always on display, both feature and disappear such differences in ways that disrupt tropic representations of disability in conventional art, documentary photography, medical textbooks, and freak show culture. Re•Vision’s approaches to curatorial practice offer interpretations of the artworks informed by the ethics, artistic practices, politics and theoretical provocations of critical disability studies. By centralising the artistic and community concern about how, to whom, and in what context we reveal these stories, we curate/contextualise videos in ways that we hope affect and enlarge the audiences’ emotional, intellectual, material, and other engagements with them. In this way, digital storytelling, by facilitating the becoming of post-humanist subjectivities and the becoming together of communities of artistic-storytellers, begins to unfold new disability ontologies in/through art.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Go to http://projectrevision.ca/videos/. Click on ‘Pedagogical Possibilities for Unruly Bodies,’ and when prompted type in the password ‘unruly.’ Please note: videos are intended for readers only and are not for public screening.

2. We use the North American terminology of ‘learning difficulties’ to signify difficulties/differences that affect information processing and recall, such as dyslexia. In the United Kingdom, these are sometimes also referred to as ‘specific learning difficulties’.

3. As part of Re•Vision’s protocol, storytellers own their stories, decide whether they wish to use their name/identifying information in their work, and retain control over the type of audience to which their story is shown.

4. As video files themselves cannot be text embedded, a still frame from each has been included, to enable readers to more easily refer between text and story. The stills are intended to provide a sample image from each story so as to better connect readers to the corresponding video, not to represent stories in their entirety. Captions are provided for accessibility.

References

- Ahmed, S. 2010. “Happy objects.” In The Affect Theory Reader, edited by M. Gregg and G.J. Seigworth, 29–51. Durham: Duke University Press.

- van Amsterdam, N., A. Knoppers, I. Claringbould and M. Jongmans. 2012. “‘It's Just the Way it is … ’ or not? How Physical Education Teachers Categorise and Normalise Differences.” Gender and Education 24 (7): 783–798.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Barthes, R. 1977. Image/Music/Text. Translated by S. Heath. New York: Hill and Wang.

- Benmayor, R. 2008. “Digital Storytelling as a Signature Pedagogy for the New Humanities.” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 7 (2): 188–204.

- Bernstein, B. 2001. “From Pedagogies to Knowledges.” In Towards a Sociology of Pedagogy: The Contribution of Basil Bernstein to Research, edited by A. Morais, I. Neves, B. Davies and H. Daniels, 363–368. New York: Peter Lang.

- Braidotti, R. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Butler, J. 2014. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”. New York: Routledge.

- Cameron, C. 2009. “Whose Problem? Disability Narratives and Available Identities.” Community Development Journal 42 (4): 501–511.

- Chandler, E., and C. Rice. 2013. “Alterity in/of Happiness: Reflecting on the Radical Possibilities of Unruly Bodies.” Health, Culture and Society 5 (1): 230–248.

- Colebrook, C. 2006. “Introduction to Feminist Theory Special Issue ‘On Beauty’.” Feminist Theory 7 (2): 131–142.

- Conquergood, D. 2002. “Performance Studies: Interventions and Radical Research1.” TDR/The Drama Review, 46 (2): 145–156.

- Dávila, A. M. 2012. Culture Works: Space, Value, and Mobility Across the Neoliberal Americas. New York: NYU Press.

- Dewhurst, M. 2010. “An Inevitable Question: Exploring the Defining Features of Social Justice Art Education.” Art Education 63 (5): 6–13.

- Ellsworth, E. 1997. Teaching Positions: Difference, Pedagogy, and the Power of Address. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Foucault, M. 1979. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Garland-Thomson, R. 2007. “Shape Structures Story: Fresh and Feisty Stories about Disability.” Narrative 15 (1): 113–123.

- Garland-Thomson, R. 2009. Staring: How We Look. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.

- Gewirtz, S. 2008. “Give us a Break! A Sceptical Review of Contemporary Discourses of Lifelong Learning.” European Educational Research Journal 7 (4): 414–424.

- Gimlin, D. L. 2002. Body Work: Beauty and Self-Image in American Culture. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Golden, J. 1996. “Critical Imagination: Serious Play with Narrative and Gender.” Gender and Education 8 (3): 323–336.

- Goodley, D., and K. Runswick-Cole. 2014. “Becoming Dis/Human: Thinking About the Human Through Disability.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 29 (2): 239–255.

- Grosz, E. A. 2010. Volatile Bodies. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Grosz, E. A. 2008. Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Halifax, N. V. D. 2004. “Imagination, Walking – In/Forming Theory.” In Provoked by Art: Theorizing Arts-Informed Research, edited by A. L. Cole, L. Neilsen, J. G. Knowles and T. C. Luciani, 174–187. Halifax: Backalong Books & Centre for Arts-Informed Research.

- Hall, K. Q. 2011. “An Introduction.” In Feminist Disability Studies, edited by K. Q. Hall, 1–10. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Harwood, V. 2009. Theorizing Biopedagogies. In Biopolitics and the “Obesity Epidemic”: Governing Bodies, edited by J. Wright and V. Harwood, 16–30. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Harwood, V. and Allan, J. 2014. Psychopathology at School: Theorizing Mental Disorders in Education. London: Routledge.

- hooks, b. 2000. Feminist Theory: From Margins to Center. London: Pluto Press.

- Kemmis, S., R. McTaggart and R. Nixon. 2014. The Action Research Planner. Singapore: Springer.

- Leahy, D. 2009. “Disgusting pedagogies.” In Biopolitics and the “Obesity Epidemic”: Governing Bodies, edited by J. Wright and V. Harwood, 172–182. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Leonard, T. and Willis, P. 2008. Pedagogies of the Imagination. New York, NY: Springer Science.

- Liddiard, K. 2015. “Theorising Posthuman Vulnerabilities.” Presentation at Theorising Dis/Ability, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, March 24.

- Lorde, A. 1984. Sister Outsider. Trumansburg: The Books.

- Lupton, D. 1996. Food, the Body and the Self. London: Sage.

- MacNeill, M. and G. Rail. 2010. “The Visions, Voices and Moves of Young ‘Canadians’: Exploring Diversity, Subjectivity and Cultural Constructions of Fitness and Health.” In Young People, Physical Activity and the Everyday, edited by J. Wright and D. Macdonald, 175–193. London: Routledge.

- Mintz, S. B. 2011. “Invisible Disability: Georgina Kleege’s Sight Unseen.” In Feminist Disability Studies, edited by K. Q. Hall, 69–90. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Raphael, R. 2013. “Art and Activism: A Conversation with Liz Crow.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 12 (3): 329–344.

- Rice, C. 2014. Becoming Women: The Embodied Self in Image Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Rice, C. 2015. “Re-thinking Fat: From Bio- to Body Becoming Pedagogies.” Cultural Studies<=>Critical Methodologies. 15 (5): 387–397.

- Rice, C. and E. Chandler. 2016, forthcoming. Project Re•Vision: Storytelling for Social Change. Guelph: Revisioning Differences Media Arts Centre (REDLAB), University of Guelph.

- Rice, C., E. Chandler, E. Harrison, M. Ferrari, and K. Liddiard. 2015. “Project Re•Vision: Disability at the Edges of Representation.” Disability & Society 30 (4): 513–527.

- Roets, G., R. Reinaart, M. Adams and G. Van Hove. 2008. “Looking at Lived Experiences of Self-Advocacy Through Gendered Eyes: Becoming Femme Fatale with/out ‘Learning Difficulties’.” Gender and Education 20 (1): 15–29.

- Saukko, P. 2008. The Anorexic Self. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Shildrick, M. 1997. Leaky Bodies and Boundaries: Feminism, Postmodernism and (bio)ethics. London: Routledge.

- Singh, P. 2015. “Performativity and Pedagogising Knowledge: Globalising Educational Policy Formation, Dissemination and Enactment.” Journal of Education Policy 30 (3): 363–384.

- Urrieta Jr., L. 2015. “Learning by Observing and Pitching in and the Connections to Native and Indigenous Knowledge Systems.” In Children Learn by Observing and Contributing to Family and Community Endeavors: A Cultural Paradigm, edited by M. Correa-Chàvez, M. Mejía-Arauz and B. Rogoff, 357–380. Waltham: Elsevier.