ABSTRACT

This paper gives an account of a series of three Zoom zine-making workshops run between March and July 2020 that were themed the political, the personal and the practical. A micro-reading of the zines is offered as data that mirror the aims of the workshops, to queer time by slowing down and creating a pause. The process of zine-making as feminist praxis is examined, and the zines themselves are discussed as data that reflect specific moments in time during the early phases of the pandemic. By inviting everyday feminist academic workers, from PhD candidates to professors to participate in a collective act of zine-making, this paper argues that a type of feminist work exists between academia and activism that subverts institutional definitions of productivity, collaboration and output.

Introduction

Feminist Educators Against Sexism (#FEAS) is an Australian-based, global feminist collective who develops arts-based interventions into sexisms in the academy. By challenging sexisms through humour, irreverence and collective action, #FEAS aims to highlight the inequalities, absurdities and dreary everydayness of sexisms in the academy. We deliberately refer to ‘sexisms’ in order to acknowledge intersectionality and gender discrimination that ‘Not only affects people identifying with the category of woman, but to identities within that category in different ways’ (Gray, Knight, and Blaise Citation2018, emphasis added, 589). Employing feminist arts-based research enables us to creatively interrupt dominant academic narratives by prioritising collective and embodied methods. These creative methods owe much to the activist artists, protest movements and ‘happenings’ of the 1960s (Leavy and Harris Citation2019) and understand art as a generative way of provoking thinking and action ‘where intensities proliferate, where forces are expressed for their own sake, where sensation lives and experiments, where the future is affectively and perceptually anticipated’ (Grosz Citation2008, 78).

Project P: was one of the #FEAS responses to the COVID-19 global pandemic. Like most global crises, the pandemic had gendered effects. Women globally were more likely to be in professions deemed ‘frontline work’, unpaid care work as well as volunteer community work (McLaren et al. Citation2020; Swan Citation2020). The closure of childcare centres and schools during periods of lockdown meant that working mothers in heterosexual relationships did the majority of home-schooling (Alon et al. Citation2020; Del Boca et al. Citation2020). The accompanying global recession meant that businesses adversely affected by social distancing, such as retail, meaning that women-dominated sectors were impacted disproportionately (Alon et al. Citation2020). As Elaine Swan (Citation2020, no page) demonstrates, feminist work shows us that the impacts of COVID-19 upon paid work and domestic labour were raced and classed as well as gendered, and ‘that it became visible that women, especially women of colour in paid and domestic carework and key worker roles were keeping the system running’.

The impact of COVID-19 on university workers was enormous, and within the sector, workers who were not stood down or furloughed were forced to make their home their workplace, meaning that women university workers’ domestic labour increased in quantity yet remained devalued and unrecognised (McLaren et al. Citation2020; Swan Citation2020). Research conducted by Cui, Ding, and Zhu (Citation2020) shows the disproportionate impact that lockdowns have had on research productivity for women in the social sciences. These combined effects were compounded by many Higher Education institutions adopting a ‘business as usual’ approach to quantifying research outputs and assessing teaching quality. At the same time, university workers reported higher levels of stress, anxiety and depression that mirrored those experienced by population writ large (Salari, Hosseinian-Far, and Jalali Citation2020). The inequalities perpetuated by the neoliberal business model that dominates Higher Education in the west were both exacerbated and spotlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

As a response to the increase in formal and informal academic labour, the gendered impacts of the pandemic and growing anxiety around job security, #FEAS developed a series of three zine-making workshops under the creative umbrella of Project P:. Each workshop engaged with a different aspect of pandemic living for academics. Project P: has a colon because we wanted to focus upon emergence and to encourage participants to make their own contribution to the beyond as new ways of being surfaced from pandemic living. The workshops brought together a total of 45 feminist academics from around the globe to co-create and make zines over Zoom. The workshops were our method for working together whilst being apart. Following the workshops, participants were invited to post their zines to Perth, Australia. In total, we received 20 zines from Australia and Canada. A zine return from Japan was thwarted by restricted postal service at the time.

The remainder of this paper locates Project P: within feminist work on zines, the need for feminist spaces within the neoliberal academy and finally offers an analysis of one zine from each of the Project P: workshops, demonstrating that how Project P: opened up participatory spaces through which participants were able to reflect upon ‘community, society, and feminist activism and politics’ (Zobl, Citation2009, 8) and to locate activism and advocacy within the political, the personal and the practical.

Zines as feminist praxis

Zines are understood to have emerged during three cultural moments. First, the ‘fanzine’ was a means through which science fiction fans in the 1930s shared stories and homage to their favourite texts (Radway Citation2011; Zobl Citation2009). Second, zines were a feature of 1970s punk subcultures, used as a way for fans to share news of events, new recordings as well as the political agenda of punk (Atton Citation2010; Watson and Bennett Citation2020). Punk zines had a deliberate ‘anti-design’ aesthetic that expressed the subcultural values of DIY, subversion, political consciousness and community (Way Citation2020). Zines re-emerged as part of the Riot Grrrl music scene of the 1990s, a feminist punk movement that started life in the USA’s Pacific Northwest. Riot Grrrl embodied the DIY spirit of punk and brought with it a feminist message from bands that were often not trained or professional musicians in order to explore radically different ways of being women musicians (Downes Citation2012).

Zines became an integral part of Riot Grrrl and, like the punk zines of the 1970s, were not just about gigs or bands but also about the politics of Riot Grrrl, of telling previously unacknowledged stories and tearing down the social institutions that had silenced them. The DIY aesthetic of these zines reflected the graphic language of punk in that they were deliberately handwritten and/or stencilled, photocopied and distributed within fan communities for a minimal cost (Triggs Citation2009). Zines have a continued presence within feminist activism that goes beyond Riot Grrrl, and zine-making now has a place in feminist history and practice and remains a means of active participation in feminist dialogue, activism and politics (Zobl, Citation2009).

Increased online political participation has led to a resurgence in zine-making amongst a new generation of feminists (Clark-Parsons Citation2017). Rather than there being a paper/online divide, contemporary feminist zines can be understood as ‘practices within the same repertoire of contemporary feminist media activism’ and that zine-making in contemporary times is part of a ‘digitally networked feminist practice’ (Clark-Parsons Citation2017, 558). Contemporary feminist zines are particularly important to feminists outside of the mainstream, especially queer, body-positive and anti-racist feminists (Nijesten Citation2017).

Whilst there are growing calls to include collections of zines, including feminist zines, into university libraries (Gabai Citation2016), zine production does not fall within the traditional scope of work that ‘counts’ as academic output. It is this intersection that Project P: focussed upon and that shapes the remainder of this paper. The #FEAS Project P: zine-making workshops brought feminist activist politics, DIY creativity and a vital interruption to institutional notions of ‘productivity’ during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Project P: and the need for feminist spaces within the neoliberal university

Contemporary universities are complex spaces. The neoliberalisation of Higher Education has reduced students to human capital, consumers who participate in a system that perpetuates western cultural elitism and to whom engaged and active citizenship is largely an irrelevance (Anderson, Gatwiri, and Townsend-Cross Citation2020; Brown Citation2015; Moreton-Robinson Citation2004). University staff and students are increasingly dissatisfied with contemporary Higher Education precisely because universities have the potential to be ‘radical and transformational spaces’ within which to challenge dominant ways of thinking, knowing and doing (Anderson, Gatwiri, and Townsend-Cross Citation2020, 1). Many university workers entered the academy because they wanted to work in radical, transformational and socially just spaces that operate for the public good, rather than as corporations that run mostly to contribute to the economic prosperity of a particular nation (Anderson, Gatwiri, and Townsend-Cross Citation2020; Mountz et al. Citation2015).

The neoliberal university is fast-paced, demanding and hierarchical (Gannon et al. Citation2019; Mountz et al. Citation2015), and it is concerned with measuring the productivity of individuals that work within it, meaning that it is designed to allow certain workers to succeed and others to fail. Within this framework, the neoliberal subject remains unnamed, and it is void of identity, meaning that it reflects the successful and is therefore white, male, middle-class, heterosexual and able-bodied. As Lipton (Citation2020) demonstrates:

Neoliberal economic rationality claims to be ‘neutral’ on gender, race and sexuality, when in fact what belies such neutrality is a masculinist, white, heteronormative logic that privileges autonomy and competition that individualises responsibility for success or failure. (5)

Even in the midst of neoliberal hierarchies […] subtle shifts in atmosphere may occur and, in those moments, different energies are released, different attunements made possible. (Gannon et al. Citation2019, 45)

Project P: the political, the personal and the practical

Methodologically, Project P: drew upon notions of queer use, creativity and queer feminism. Theoretically, Project P: was oriented to queer theory for two key reasons. First, we identify as queer politically and personally and consider ourselves as academic misfits. The queer theory therefore offers us ways to think through our lives as activists, artists and academics and opens us up to radical possibilities of private and professional personhoods. Second, thinking with the queer theory enabled us to design a project that queered neoliberal notions of usefulness and time and allowed us to subvert the ways in which time and productivity are framed within the contemporary western university.

In order to do this, we drew from two key texts, Sara Ahmed’s What’s the Use? (Citation2019) and Jack Halberstam’s In a Queer Time and Space (2005). In What’s the Use? (2019), Ahmed offers an exploration of use, including the relationship between people, things and use, and the use of people by other people. Ahmed’s work is use full as an analytical framing for Project P: because, in multiple ways, it engages with use and queered notions of ‘usefulness’ within academic life. First, Ahmed writes about things that are ‘used up’ as encompassing waste, energy and exhaustion and how ‘to consider using up is to reflect on use as a system: when efficiency is something that is valued, it becomes a value system’ (55). Overwhelming demands on time, a lack of care, and a disregard for the quirky and creative mean that those who sit outside of neoliberal subjecthood within the academy often find themselves exhausted, out of time and feeling literally used up by the neoliberal academic machine (Ahmed Citation2019; Gannon et al. Citation2019; Halberstam Citation2011; Mountz et al. Citation2015). By subverting notions of productivity and what it means to produce something in a timely manner, Project P: enabled a moment of pause, time to reflect on the political, personal and practical and feminist relationships to the pandemic.

In order to think with time, we turned to Halberstam’s work on queer times and queer places. This was particularly useful to Project P: because most participants were experiencing some form of lockdown when the workshops took place. COVID-19 lockdowns precipitated new ways of living-working and can be thought of as liminal spaces (Rinelli Citation2020). Here, we understand liminality as an in-between space where ‘positions and relations are uncertain and floating’ (Danielsson and Kemani Citation2021, no page), and we also recognise liminality as a generative space within which to challenge norms (ibid.). In a Queer Time and Place, Halberstam demonstrates the many creative ways in which notions of time, space and subjectivity can be subverted and how ‘queer uses of time and space develop … according to other logics of location, movement, and identification’ (Citation2005, 1). The Zoom platform used for our workshops was itself a liminal space, and as zine makers and workshop participants, we were simultaneously alone and together, embodied and disembodied. Project P: invited participants to use time queerly by inviting academic workers of all career stages, nationalities, identities and ethnicities to come together and to create a zine of their own that engaged with the political, the personal and the practical. Project P: therefore repurposed time and flattened the hierarchies inherent within the neoliberal academy. Most participants had never made a zine before, and those had tended to be queer, BIPOC and/or early career academics who then taught those in senior positions about zine-ing. The DIY nature of Project P: zine-making meant that it also literally re-used and repurposed used-up items such as old newspapers, magazines, post-it notes, stickers and business cards. Such ‘improper’ use of objects and time thus contributed to the queering of use precipitated by Project P:.

A key aim of Project P: was to create moments of pause during a globally anxious time, and because participants were joining us from international locations, it was always part of the working day of some of our participants, offering a deliberate interruption to the ‘business enterprise of academic life [and] a work rhythm that is rushed, riddled with anxiety and pressure to be ever present’ (Mountz et al. Citation2015, 1244). We had a deliberate strategy for creating such moments. Each session lasted for 2 h, meaning that participants had to take a break from their regular activities in order to engage in the workshops. Although participation depended upon the use of an electronic device, the zine-making itself was true to the DIY ethos of #FEAS and zine-making and participants used pens, paper, glue, cut-up pieces of magazines and paper to create their zines. We asked participants, where possible, to angle their laptops so that we saw each other’s hands, making, when we looked up at the screen. This performative moment created a sense of togetherness, of a collective endeavour, even though most of us were in a state of lockdown that enhanced the notion of the individual academic. We also talked whilst making, and these conversations were deliberately not recorded in order to preserve the zines themselves as the sole data for the project ().

The making and the conversations amongst feminists co-created a space that slowed down time, amplified voices that are not white, straight, male and/or able-bodied and created moments of joy and pleasure within the panic of the pandemic.

The decision to ask participants to send their zines by post, rather than to scan and email them, was a deliberate decision that lent weight to the idea of slowing things down and creating space for pause. This enabled participants to continue working on their zines once the workshop was over and also ensured that we, as participant researchers, remained connected to the materiality of zine-making practice and that the zines remained distinct from digital media (Clark-Parsons Citation2017). The posting process generated a physical pause in the project, as the researchers waited for mail to arrive and to ceremoniously ‘unbox’ them as a performance (see https://www.thesociologicalreview.com/feas-performing-project-p-the-official-unboxing-of-political-personal-and-practical-zines/).

We chose to focus upon the themes the political, the personal and the practical for several reasons. The personal and the political are deeply connected to feminist history, and we wanted to acknowledge our feminist roots as well as paying attention to the intersections of race, social class and queerness that are a vital part of contemporary feminisms. The pandemic was also used politically by populist leaders such as Modi in India and Trump in the USA, as Arundhati Roy illustrates in her 2020 essay The Pandemic is a Portal. It also shrunk our spheres of existence to the personal space of home: at the times that the workshops were run all participants were conducting their work from home and we acknowledged this through our use of the personal theme.

The practical theme addressed two issues. As the pandemic took hold and many locations went into full or partial lockdown and university workers conducted their daily lives from home, there were calls from our institutions to conduct ‘business as usual’, to remain productive and to organise our days so that we could balance the pressures of family and work. In response, the practical zine workshops used listing as a mechanism through which to explore this aspect of pandemic living-working. The practical theme also had the intention of acknowledging feminist activism, praxis and the DIY ethos of zine-making.

Each Zoom workshop began with specific embodied practices that were designed to bring people together in a collective experience of feminist activity. These introductory responsive practices of hand to page mark-making, breathing, drawing, writing, listening and responding helped to generate a collective sense of embodied attention through shared ‘success’ of simple tasks. This relaxed state made way for the second instructional part of the workshop, which saw participants making a series of specific folds in the now hand-marked piece of A4 paper to create their zine template. Whilst a simple activity in itself, the video platform added a layer of complexity to the process of transferring haptic instructions of precise folding, creasing and unfolding which caused much hilarity, several ‘failures’ and ensuing discussion about pressure and productivity. Time here was given precedent and the failures made room for lively and generative exchange in an atmosphere that disrupted academic hierarchies and valued vulnerability. Transforming this single A4 page into an artefact of use, already imbued with their creative mark-making from the embodied response practices, enabled each participant to continue their zine-making with confidence and creative licence to respond to the political, the personal and the practical themes of the workshops.

The political workshop involved each participant receiving a postal pack ahead of the event that included zine-making materials and instructions. The delay in post during COVID-19 restrictions generated an enforced pause before we could run the workshop, whilst we waited for participants to receive the packs. The postal pack also included a letter-sized piece of paper with the proliferation of P words. Participants were asked to choose one of the P words that were significant to them and which provided a key provocation for their zine. Participants were asked to cross out words on the page of ‘P’ words to create a micro-poem using a technique of erasure poetry (Ruefle Citation2006; Kleon Citation2010; Citation2012) useful in re-making texts to create new meanings. This process of active subtraction was useful in attending to a creative critique on the pressure of productivity, and it also gave participants an opportunity to think with the theme and to generate content to be cut up or integrated into their zine.

The personal workshop drew participants from a post on #FEAS Facebook group that had asked members to reflect upon their feminist origin stories. The volume and richness of responses from this post encouraged us to continue Project P: by asking contributors to take part in a personal themed online zine workshop. Whilst we are aware of the ways in which western white feminism and the notion of ‘origin’ have been critiqued (Hemmings Citation2005), we were motivated by feminist work that aims to capture t experience beyond the confines of the academy and that takes place within oral history, shared experience and storytelling (Wånggren Citation2016). The creative practice for this workshop was breath, and participants were guided through a breathing exercise whilst the origin stories of their fellow workshop participants were read aloud. Drawing breath was used here because it physicalises breathing in a process that brings attention to the whole body, sensations of rhythm, time and listening through marks made with pencil to paper. It is a practice used to ‘heighten awareness and become more open to deeply responding … to become curious, to linger, to develop a deeper interest, and to feel’ (Blue Citation2018, no page). The resulting page of drawn breath served as background for the zines and the personal origin stories that emerged. These origin stories were read out as a single long monologue, and participants were invited to write down words they heard or responded to in an improvised accumulation of responsive editing in the moment (Pollitt Citation2017). This created new entangled stories, mixing fact with fiction and provoked the basis of many of the personal zines created. The pressure of attending to one’s ‘personal’ story was diffused in the collective listening with permission given to assume another participant’ story to creatively reconfigure and attend to old experiences.

The practical workshop focussed on the concept of lists and list-making and saw participants arrive with their own lists that were written on the back of receipts, in journals, on envelopes or scraps. Reading them out loud in a round Zoom robin prompted shared sighs, agreements and in some cases more tasks or reminders to add to their own list. In the process of zine-ing queer economies of exchange emerged: for example, the gift via of half an hour of time was passed on to one participant by another for a specific task. The pandemic made it difficult to focus on goals and keep productive, and some participants were spending ‘all day’ talking in virtual meetings and saying nothing, achieving nothing and crossing nothing off their list. We harnessed this sense of frustration by working with the lists in a timed series of creative writing experiments that were used to actively expand and respond to the concept of list-making. These experiments formed the content for the zines and the practical application of ‘pausing’ was amplified in the deliberation of each list item that ranged from the banal and everyday to manifesto-style statements.

We now offer an analysis of three zines, one from each of the Project P: workshops. The analysis is slow, deliberate and represents an unfolding and a slow, reflective and theoretical reading of each of the three zines. In this way, we deliberately bring to the paper a moment of pause, a time to reflect and a deep engagement with how each of the zine makers represents themselves and the intersections of gender, race, sexuality and social class that encompass feminist engagement with the pandemic.

The zines: pausing and reading slowly

Analysing one zine from each of the three workshops demonstrates how feminist spaces for activism and advocacy were opened up within the workshops, how the zines produced represented specific moments in time during the pandemic as well as how each of the zine makers imprinted their identities onto their creations (). The analysis is deliberately slow and invites the reader to pause with us as we examine each page of the zines, make links between them and demonstrate how zines can (co)create meaning, value, knowledge and, most importantly, challenge the academic personhood most valued by the neoliberal university through creative expression ().

The political

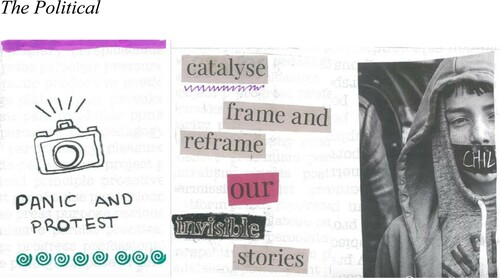

As the previous section outlined, participants in this workshop were provided with a series of ‘P’ words from which to choose. The maker of this zine chose ‘panic’ and ‘protest’ to represent feminist advocacy, the politics of identity as well as Black Lives Matter and queer political activism through the words and pictures they use in their zine. The front cover of the zine displays the phrase ‘panic and protest’ and includes a hand-drawn image of a camera. The camera is active, the flash is going off signifying the visual capturing of a moment in time. The zine maker focuses specifically upon silenced voices and plays with this idea in several ways. First, there is the use of a quote from Roy (Citation2004) which reads, ‘There's really no such thing as the “voiceless”. There are only the deliberately silenced, or the preferably unheard.’ By using Roy’s words in the zine, the author reminds us of the importance of listening to subaltern voices and of including those voices within feminist politics, activism and academia.

The zine’s theme of silenced voices continues throughout its pages and is represented by a statement made from words cut from elsewhere and which reads

catalyse

frame and

reframe

our

invisible

stories

The theme continues and is represented visually by a photograph of a child with tape across their mouth. Children are often silenced within Political debate but are also a vital political force, seen, for example, in the School Strikes for Climate and various global protest movements including Freedom for Hong Kong and Black Lives Matter. The zine continues its exploration of silence through its inclusion of a poem written by the author entitled Unravel (Reprise) that reads

unravel a woman

peel back

the layers she shows

take each woven word

from her lips;

letters and sounds,

knotted ends

too many colours

unravel until you are left

with just her

The poem reminds us of Roy’s words by its phrase ‘take each woven word from her lips’, which suggests a deliberate silencing. The poem is also an example of queer use, it is a reprise, suggesting it has another, it is a continuation. It has also been literally cut and pasted onto the page of the zine from another source, and its origin is unknown. It is therefore re-used. Ahmed (Citation2019) writes about queer life as ‘how we get in touch with things at the very point at which they, or we, are worn or worn down’ (197) and the unravelling that the poem implies is a wearing down, but one that it both purposeful and empowering, and that leaves the subject of the poem, and the poem itself in a liminal space.

The political zine also contained a secret pocket within its pages, and the pocket held a series of images of protest, for example, a silent vigil held following the Pulse nightclub shooting in Florida, 2016, a group of African American protesters holding a sign that reads ‘hands up, don’t shoot’ at a rally in 2016, and an image of a Muslim woman wearing a hijab and holding a #BlackLivesMatter (#BLM) protest placard. The latter image is accompanied by text that has been highlighted in key places and which talks about being an activist photographer, and that one of the unexpected outcomes is to ‘expose the humanity, the people behind the protest’ and which asks the question, ‘How do we stand in solidarity with people whose voices are silenced?’ This question is something that we grapple with as feminist activists and academics, and who hears is as important a question to consider as who speaks. As a movement against state violence, #BLM was co-founded by two black queer women who subvert ‘the notion of who a political leader should be’ (Cohen and Jackson Citation2016, 777). Dernikos (Citation2016) writes about how #BLM has a ‘populist-vibe’ that invites anyone to ‘consider themselves a leader’, but also about the complicated ways in which the queerness of the movement’s founders plays out through the erasure. The political zine, with its inclusion of #BLM and the Pulse nightclub shooting, forces us to see the invisible and to hear the silenced: children, women, queer people, people of colour and all of their intersections, and how #BLM and protests that seek to address issues of social justice are important contributions to the democratic process (Jackson Citation2020). That this zine was created by an academic university worker, which reminds us that the academy is itself a site of oppression and erasure and that ‘black feminists occupy an in-between’ community and academy space that is enabling, though this is often disregarded’ (ibid. 778). Within the Australian context, the Aboriginal sociologist Moreton-Robinson (Citation2000) speaks of a similar in-betweenness and of an abstraction from the embodied experience of racism afforded to white middle-class feminists who dominate ‘women’s places’ in the academy. The Project P: Political zine discussed here shows the hidden, the faint and the often undetected and offers an engaged and intersectional politics throughout its pages. The Project P: Political workshop was held on 25 April 2020, almost a month to the day before the murder of George Floyd by the Minneapolis police on 30 May 2020.

The personal

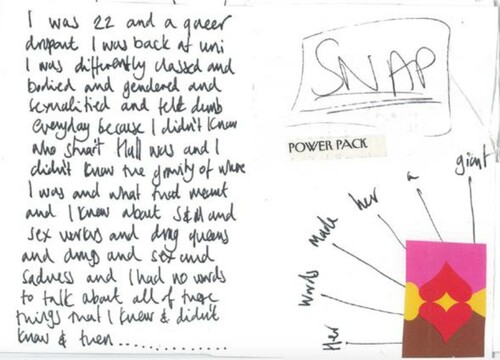

We now turn to discuss and analyse an example from the personal zine workshop (). As outlined earlier, the motivation for this workshop was a post we had made on the #FEAS Facebook group that asked members to share their feminist origin stories. Those that had shared their stories were invited to attend the workshop. The zine we have chosen to focus upon here tells a queer, working-class origin story. It is a story of both not fitting in and of finding a place within the academy. The front cover features a cut and pasted statement that reads, ‘Now is the time to start listening’, and the author has handwritten ‘ORIGIN STORIES how you become a feminist’ as an accompaniment. On the first page, the author shares the following story:

I was 22 and a queer dropout I was back at uni I was differently classed and bodied and gendered and sexualitied and felt dumb everyday because I didn’t know who Stuart Hall was and I didn’t know the gravity of where I was and what that meant and I knew about S&M and sex workers and drag queens and drugs and sex and sadness and I had no words to talk about all of these things that I knew and didn’t know and then …

The reflection continues, ‘And my hair, and my politics and my body and my lovers and my laughter make me who I am’. Gone is the melancholia of the first part of the reflection, and the author here expresses righteousness, pride and joy in her queer self which again brings us back to Halberstam’s work on queerness and failure and the notion that, ‘gender failure often means being relieved of the pressure to measure up to patriarchal ideals, not succeeding at womanhood can offer unexpected pleasures’ (Citation2011, 4). Through the reflection on her feminist origin story, the author seems to find her place within the academy in real-time, taking us from a place of weariness to one of joy.

The practical

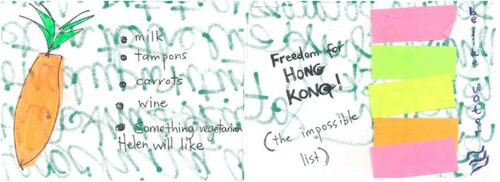

Finally, we turn to the practical zine (). We have chosen to focus upon this zine, as it demonstrates well the juxtaposition of the mundane and the consequential. The zine is almost entirely handwritten and uses everyday office supplies like post-it notes and highlighter pens, uses that illustrate the notion of the practical. The listing that shaped the score for this workshop provides both a background and the substantive content of this zine, for example, the maker provides us with a shopping list that includes the item ‘something vegetarian Helen will like’. Helen is unknown to the reader, she could be a friend, sibling, child or partner and the inclusion of Helen on the list reminds us of how intertwined our work and home lives became during the pandemic, especially when we see another note that states ‘BUY NOTEBOOKS to write more lists’. This blurring of the private and the professional acts to challenge the notion of ‘business as usual’ during the pandemic by making the contrasting lists appear strange to one another. The practical zine maker also reflects upon the practical process of the zine-making and asks ‘Hmmm … .do I understand what Jo is asking???’ A hand-drawn caricature answers ‘Not sure’.

The practical zine demonstrates the possibilities of forcing open feminist spaces such as Project P: within the neoliberal academy. Mountz et al. write about how ‘care full scholarship’ should be about engaging different publics and ‘engaging in activism and advocacy’ (Citation2015, 1245). Such an engagement is not always possible within the chaotic, individualised and quantified notions of productivity that the neoliberal academy thrives upon. However, in a moment of pause, the practical zine maker draws our attention to Hong Kong. Since February 2019 until the COVID-19 pandemic arrived, Hong Kong had been in an almost constant state of protest (Laikwan Citation2020). Starting with opposition to a proposed extradition bill that would see those accused of ‘serious crimes’ potentially being extradited to mainland China for trial, the protests became about five demands: the removal of the extradition bill; an investigation into police brutality during the protests; the release without charge of arrested protestors; the retraction of the labelling of protestors as ‘rioters’ and the resignation of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam. During the protests, hands raised with finger’s spread came to signify the five demands. In addition, during the protest period, many ‘Lennon Walls’ were created around Hong Kong and protestors used colourful post-it notes to post messages of support to the protest movement. On 30 June 2020, the Standing Committee of the People’s Republic of China enacted a Security Law which (amongst other things) outlawed protest slogans, including Lennon Walls and the five demands hand gesture (Buckley, Bradsher, and May Citation2020). News reports from the time suggested that protesters would hold blank pieces of paper and create Lennon Walls made up of blank post-it notes. In an act of both activism and advocacy, the practical zine maker writes ‘Freedom for HONG KONG! (the impossible list)’, along with five, differently coloured blank post-it notes and the phrase ‘be like water’, a slogan first uttered by Hong Kong film star Bruce Lee that became a protest strategy during 2019 where protesters would appear and then disappear, ‘like water’ (Holbig Citation2020; Ting Citation2020).

By contrasting the banality of a shopping list including ‘something for Helen’, the need to buy notebooks for work and the five demands of the Hong Kong protesters, the zine maker shows us that life-work during the pandemic meant that all of these things were simultaneously part of her lived reality. The practical zine also links to the themes of the hidden, faint and often undetected traces of mundane frustrations and activist work that we do everyday. The Hong Kong protests may be changed, but our practical zine author follows their trace and does not allow us to forget them in an act of feminist advocacy and activism.

Whilst these zines are directly illustrative of the workshop themes, other zines included more abstract and open-ended responses suggestive of other speculative and affective impacts of the political, the personal and the practical. For example, one zine, created by an artist, was filled entirely with repeated graphite marks with the single word ‘pause’ pencilled on both the front and back covers; another housed a cut-out window with a miniature bunch of coloured flowers stuck in the paper ‘windowsill’; another contained nonsensical images and fragmented words; and another was a mini feminist cookbook containing a recipe to ‘Mix this Bitches’. All of the zines were suggestive of ongoing pressure, repetitive reminders of self-care and politics, and foreground an expanded range of creative responses and ‘usefulness’ that this kind of feminist work, exchange and activism in the academy, ignites.

Conclusion

This paper has offered an account of Project P:, three online feminist zine-making workshops that were carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. We have linked our work to the scholarship of zines and to the importance of forcing open creative, feminist spaces of activism within the neoliberal academy. We have also offered a deliberately slow and detailed analysis of one zine from each of the three workshops, illustrating the nuances brought to zine-making by each of their creators, as well as showing that how all three engage with the hidden, faint and undetected traces of non-normative subjectivities within contemporary Higher Education.

Our zines therefore contribute to scholarship that positions zine-making as feminist autobiographical acts

which can help map interpersonal lives and […] demonstrate the affects and effects of feminist cultural production on individuals […] the norm of citing your own situational knowledges and experiences provides rich data for scholars looking to map individual lives and community scenes. (Chidgey Citation2013, 667)

Project P: created a space for generative pause, a liminal space where participants were alone and together at the same time, an activist space, a space of reflection and a chance to slow down for a moment and create something both useless and meaningful. We have demonstrated throughout our paper the necessity for alternative spaces within the neoliberal academy, during the pandemic these spaces became even more vital as work-home-life pressures mounted and seemed insurmountable for many. In turning back to Ahmed, we see again how collective, creative spaces enable the telling of different stories and how

we have to create our own support systems, queer handles - how we hold on, how life can go on - when we are shattered, because we are shattered. No wonder then: the stories of exhaustion of inhabiting worlds that do not accommodate us, the stories of the weary and the worn, the teary and the torn are the same stories of inventiveness, of creating something, of making something. (Ahmed Citation2019, 219)

Acknowledgements

The authors of the paper acknowledge that our work was carried out on the unceded lands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across the lands and waters of Australia. Emily lives and works in Naarm (Melbourne) on the stolen lands of the Wurundjeri People of the Kulin Nation. Jo and Mindy live and work in In Whadjuk Noongar boodja (Perth) on the stolen lands of the Noongar people. We respectfully acknowledge Elders past, present and emerging and acknowledge that a treaty is yet to be signed. Ethical approval for this research was granted by the Edith Cowan Human Research Ethics Committee, approval number 2020-01285-ECU.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emily M. Gray

Emily M. Gray, originally from Walsall, UK, is a Senior Lecturer in Education Studies at RMIT’s School of Education. Her interests within both research and teaching are interdisciplinary and include sociology, cultural studies and education. Her key research interests lie with questions related to gender, social justice, student and teacher identity work within educational policy and practice and with wider social justice issues within educational discourse and practice. She also researches popular culture, public pedagogies and audience studies, particularly online ‘fandom’ and media and popular culture as pedagogical tools. Emily is co-founder, with Mindy Blaise and Linda Knight of Feminist Educators Against Sexism #FEAS, an international feminist collective committed to developing arts-based interventions into sexism in the academy.

Joanna Pollitt

Joanna Pollitt is an interdisciplinary artist and Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Edith Cowan University. Her work is grounded in a twenty-year practice of working with improvisation as methodology across multiple performed, choreographic and publishing platforms. Jo's practice-led scholarship is centred in research translation through feminist, anti-colonial, embodied and interdisciplinary methods. She is co-founder of The Ediths, artist-researcher with #FEAS-Feminist Educators Against Sexism, co-founder of BIG Kids Magazine and lectures in dance improvisation at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts. Her debut novella The dancer in your hands < > was released by UWA Publishing in 2020.

Mindy Blaise

Professor Mindy Blaise is a Vice Chancellor's Professorial Research Fellow and Co-Director of the Centre for People, Place & Planet, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Western Australia. She is also co-founder of several research collectives, such as #FEAS, Feminist Educators Against Sexism; the Common Worlds Research Collective; and The Ediths. Her interest in feminist and 'post‘ theories, creative methodologies, and her identity as a white settler woman influences how she approaches research.

Feminist Educators Against Sexism #FEAS is an international feminist collective committed to developing interventions into sexism in the academy and other educational spaces. We use a mix of humour, irreverence, arts practices as well as collective action to interrupt and disarm both everyday and institutional sexism within Higher Education and other spaces: www.feministeducatorsagainstsexism.com

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2019. What’s the Use: On the Uses of Use. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2020. “Complaint and Survival.” Feminist Killjoys. https://feministkilljoys.com/2020/03/23/complaint-and-survival/

- Alon, Titan M., Matthias Doepke, Jane Olmstead-Rumsey, and Michele Tertilt. 2020. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality.” NBER Working Paper No. 26947. April 2020.

- Anderson, Leticia, Kathani Gatwiri, and Marcelle Townsend-Cross. 2020. “Battling the ‘Headwinds’: The Experiences of Minoritised Academics in the Neoliberal Australian University.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 33 (9): 939–953.

- Atton, Chris. 2010. “Popular Music Fanzines: Genre, Aesthetics and the ‘Democratic Conversation’.” Popular Music and Society 33 (4): 517–531.

- Blue, Lily. 2018. Drawing Breath; Visual Response Journal. Perth: Art Gallery of Western Australia. https://artgallery.wa.gov.au/learn/drawing-breath.

- Brown, Wendy. 2015. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. New York: Zone Books.

- Buckley, Chris, Keith Bradsher, and Tiffany May. 2020. “New Security Law Gives China Sweeping Powers Over Hong Kong”. The New York Times, June 29. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/29/world/asia/china-hong-kong-security-law-rules.html.

- Chidgey, Red. 2013. “Reassess Your Weapons: The Making of Feminist Memory in Young Women’s Zine.” Women’s History Review 22 (4): 658–672.

- Clark-Parsons, Rosemary. 2017. “Feminist Ephemera in a Digital World: Theorizing Zines as Networked Feminist Practice.” Communication, Culture and Critique 10: 557–573.

- Cohen, Cathy J., and Sarah J Jackson. 2016. “Ask a Feminist: A Conversation with Cathy J. Cohen on Black Lives Matter, Feminism and Contemporary Activism.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 41 (4): 775–792.

- Cui, Ruomeng, Hao Ding, and Feng Zhu. 2020. “Gender Inequality in Research Productivity During the COVID-19 Pandemic”. Harvard Business School: Working Paper.

- Danielsson, Magnus, and Mike Kemani. 2021. “When Saga Norén Meets Neurotypicality: A Liminal Encounter Along The Bridge.” In Normalizing Mental Illness and Neurodiversity in Entertainment Media, edited by Maylandia Johnson, and Christopher J. Olson. New York: Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Normalizing-Mental-Illness-and-Neurodiversity-in-Entertainment-Media-Quieting/Johnson-Olson/p/book/9780367820527.

- Del Boca, Daniela, Noemi Oggero, Paola Profeta, and Maria Cristina Rossi. 2020. “Women's Work, Housework and Childcare, before and during Covid-19”. CESifo Working Paper, No. 8403, Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich.

- Dernikos, Bessie P. 2016. “Queering #BlackLives Matter: Unpredictable Intimacies and Political Affects.” Juomen Queer-tutkimusken Seurum Lehti 1–2: 46–56.

- Downes, Julia. 2012. “The Expansion of Punk Rock: Riot Grrrl Challenges to Gender Power Relations in British Indie Music Subcultures.” Women's Studies 41 (2): 204–237.

- Gabai, Sara. 2016. “Teaching Authorship, Gender and Identity Through Grrrl Zines Production.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 18 (1): 20–32.

- Gannon, Susanne, Carol Taylor, Gill Adams, Helen Donaghue, Stephanie Hannam Swain, Jean Harris-Evans, Joan Healy, and Patricia Moore. 2019. “‘Working on a Rocky Shore’: Micro-Moments of Positive Affect in Academic Work.” Emotion, Space and Society 31: 48–55.

- Gray, Emily M., Linda Knight, and Mindy Blaise. 2018. “Wearing, Speaking and Shouting About Sexism: Developing Arts-Based Interventions Into Sexism in the Academy.” The Australian Educational Researcher 45: 585–601.

- Gray, Emily M., and Lucy Nicholas. 2019. “You’re Actually the Problem’’: Manifestations of Populist Masculinist Anxieties in Australian Higher Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 40 (2): 269–286.

- Grosz, Elizabeth. 2008. Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Halberstam, Jack. 2005. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. New York: New York University Press.

- Halberstam, Jack. 2011. The Queer Art of Failure. London: Duke University Press.

- Hemmings, C. 2005. “Telling Feminist Stories.” Feminist Theory 6 (2): 115–139.

- Holbig, Heike. 2020. “Be Water, My Friend: Hong Kong’s 2019 Anti-Extradition Protests.” International Journal of Sociology 50 (4): 325–337.

- Jackson, Sarah J. 2020. “Backlash, Intersectionality and Trumpism.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 45 (2): 295–302.

- Kleon, A. 2010. Newspaper Blackout. New York: Harper Perennial.

- Kleon, A. 2012. Steal Like An Artist. New York: Workman Publishing.

- Laikwan, Pang. 2020. “Identity Politics and Democracy in Hong Kong’s Social Unrest.” Feminist Studies 46 (1): 206–215.

- Leavy, Patricia, and Anne Harris. 2019. Contemporary Feminist Research from Theory to Practice. New York, London: The Guilford Press.

- Lipton, Briony. 2020. Academic Women in Neoliberal Times. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Malisch, Jessica L., Breanna N. Harris, Shennen M. Sherrer, Kristy A. Lewis, et al. 2020. “In the Wake of COVID-19.” Academis Needs New Solutions to Ensure Gender Equality. PNAS 117 (27): 15378–15381.

- Marginson, Simon. 2009. “Is Australia Overdependent on International Students?” International Higher Education 54 (Winter): 10–12.

- McLaren, Helen J., Karen R. Wong, Kieu Nga Nguyen, and Komalee Nadeeka Damayanthi Mahamadachchi. 2020. “Covid-19 and Women’s Triple Burden: Vignettes from Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Vietnam and Australia.” Social Sciences 87 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9050087.

- Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. 2000. Talkin’ Up to the White Woman: Indigenous Women and Feminism. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press.

- Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. 2004. “Whiteness, Epistemology and Indigenous Representation.” In Whitening Race: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism, edited by Aileen Moreton-Robinson, 75–88. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Mountz, Alison, Anne Bonds, Becky Lloyd Mansfield, Hyndman Senna, Walton Roberts Jennifer, Basu Margaret, Whitson Rani, et al. 2015. “For Slow Scholarship: A Feminist Politics of Resistance Through Collective Action in the Neoliberal University.” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 14 (4): 1235–1259.

- Nijesten, Nina. 2017. “Unruly Booklets: Resisting Body Norms with Zine Authors.” DiGest: Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies 4 (2): 75–88.

- Oleschuck, Merin. 2020. “Gender Equity Considerations for Tenure and Promotion During COVID-19.” Canadian Sociological Association. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12295.

- Pollitt, Jo. 2017. “She Writes Like she Dances: Response and Radical Impermanence in Writing as Dancing.” Choreographic Practices 8 (2): 199–218.

- Radway, Janice. 2011. “Zines, Half Lives and Afterlives: On the Temporalities of Social and Political Change.” PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 126 (1): 140–150.

- Rinelli, Lorenzo. 2020. “Andante Adagio: Exposed Life and Liminality in Times of Covid-19 in Italy.” Theory and Event 23 (4): 30–40.

- Roy, Arundhati. 2004. “Peace and the New Corporation Theology”. The 2004 Sydney Peace Prize Lecture. https://www.sydney.edu.au/news/84.html?newsstoryid=279.

- Ruefle, Mary. 2006. Little White Shadow. Washington: Wave books.

- Salari, N., A. Hosseinian-Far, R. Jalali, et al. 2020. “Prevalence of Stress, Anxiety, Depression among the General Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Globalization and Health 16 (57), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w.

- Swan, Elaine. 2020. “COVID-19 Foodwork, Race, Gender, Class and Food Justice: An Intersectional Feminist Analysis.” Gender in Management 36 (7-8), https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-08-2020-0257.

- Thornton, Margaret. 2013. “The Mirage of Merit.” Australian Feminist Studies 28 (76): 127–143.

- Ting, Tin-yuet. 2020. “From ‘Be Water’ to ‘Be Fire’: Nascent Smart Mob and Networked Protests in Hong Kong.” Social Movement Studies 19 (3): 362–368.

- Triggs, Teal. 2009. ‘Do It Yourself’ Girl Revolution: Ladyfest, Performance and Fanzine Culture. London: London College of Communication.

- Wånggren, Lena. 2016. “Our Stories Matter: Storytelling and Social Justice in the Hollaback! Movement.” Gender and Education 28 (3): 401–415.

- Watson, Ash, and Andy Bennett. 2020. “The Felt Value of Reading Zines.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41290-020-00108-9.

- Way, Laura. 2020. “Punk Is Just a State of Mind: Exploring What Punk Means to Older Punk Women.” The Sociological Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120946666.

- Zobl, Elke. 2009. “Cultural Production, Transnational Networking, and Critical Reflection in Feminist Zines.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 35 (1): 1–12.