ABSTRACT

The word ‘care’ has been removed from Norway’s most recent framework for early childhood teacher education. According to ECEC practice policy, care is foundational in ECEC and teachers are expected to care, yet caring is not mentioned in the Framework’s description of ECEC, nor is it included as a knowledge or skill goal. Why does care occupy a secondary position to education in ECEC policy development? This article uses Cathrine Malabou’s concept of plasticity and the image of the concubine to stretch conceptions of care in ECEC. Tronto’s care-ethics and the image of a concubine, who bears children for a man, but does not enjoy a legal status in society act as a catalyst for thinking differently about how care is positioned and used politically, domestically and professionally.

Introduction

Because the work and reproductive capabilities of concubines were central to the vitality of the state, the institution of concubinage was important as an effective means of controlling them. (Mack Citation2006, 219)

The role of care in early childhood education and care (ECEC) is increasingly marginalized in policy and practice as the field moves toward academization and professionalization (Ailwood Citation2020). Some associate these developments with what has been termed the global education reform movement (GERM), in which education sectors borrow from each other and align with market values and concerns such as efficiency and accountability (Ringsmose Citation2017). In response, there is also increased scholarly interest in defining and re-defining what care is or can be in ECEC policy and practice (Ailwood Citation2020; Langford Citation2019; Myers, Hostler, and Hughes Citation2017). The recent endeavor to redefine care has included explorations of care in relation to power and politics. The concept isoften extended with posthuman perspectives that emphasize the interdependencies of the human and nonhuman environment. Joan Tronto’s (Citation1993, Citation1998) development of feminist care-ethics has informed work on care in relation to politics and power, while posthuman perspectives often draw on Maria Puig de la Bellacasa’s (Citation2017) speculative work on care as both a human and nonhuman practice that underlies material and social relations. This work is part of a movement to ‘save’ the care in ECEC through re-defining it. In this article, I build further on these strands, but rather than reconceptualise care as a concept, I want to work speculatively, and explore the place of care from the perspective of care itself, using the figure of a ‘concubine’.

The care that occurs in ECEC is part of the global web of paid, unpaid and nonprofit care-work that provides the glue to society (Lynch Citation2007; Baines etal. Citation2020) and that is overwhelmingly performed by women (Folbre and Nelson Citation2000; Suh and Folbre Citation2016). Care-work provides and enables daily functioning. For anything anywhere to function, relationships of care, both human and nonhuman, are necessary (Puig de la Bellacasa Citation2017). Care is a foundational element in ECEC, though the ‘care’ element is often weakly conceptualized, or not conceptualized at all (Moss, Boddy, and Cameron Citation2006).

In my doctoral work (Aslanian Citation2020), I described how little by little and almost unintentionally during the policy making process, policy makers removed the word ‘care’ from Norway’s most recent Framework for Early Childhood Teacher Education (ECTE) (Ministry of Education and Research (MER) Citation2012). Policy makers explained the gradual removal of care as the byproduct of an effort to professionalize the field and align it with the education sector, after years of belonging to the Ministry of Children and Families (Aslanian Citation2020). Each removal of the word was intentional, but it was not their premeditated intention to remove the word completely from the policy text. The effective erasure of care from ECTE policy occurred simultaneously with the governmental push to modernize the sector (Aasland Citation2010) amid the marked increase in infant and toddler participation in ECEC centers from 37% in 2000 to 80% in 2012 (Statistics Norway Citation2020).

Paradoxically, the concept of care figured and continues to figure strongly in practice policy, often in relation to children’s rights (MER Citation2009, Citation2011; NOU Citation2007). ECEC educators are expected to care, though the subject of care is not included as knowledge, skill or competency goal in the ECTE Framework (2012). Though absent from formal policy, the subject of care is present in National Guidelines for ECTE (MER Citation2012), which are ‘professional recommendations on how the academic content of the kindergarten teacher education shall be developed’. The guidelines are ‘not set by the Ministry’ but, ‘important guidelines, prepared by the academic communities themselves, to assist the institutions in preparing their program plans and subject plans’ (MER Citation2017). The subject of care continues to be taught in ECTE by an overwhelmingly female workforce of ECTE educators, within the subject area entitled ‘Children’s development, play and learning’, despite the lack of formal regulations ensuring it be taught.

The modernization of ECTE was followed up in 2017 with a revised framework for practice that increased demands on ECEC centers on documentation and progression (UDIR, 2017) without additional funding to implement changes. The demands and the lack of funding delegated to implement them resulted in what many professionals continue to experience as unacceptable working conditions at ECEC centers. A so-called ‘kindergarten revolt’ grew out of a partnership between academia and the practice field in which preschool staff across Norway share their personal stories of not being able to provide adequate care to children due to inadequate staffing conditions (Løvås Citation2018) in an aptly titled movement #unjustifiable. By far, the majority of stories are told by women.

The subject of care in ECEC is a meeting point between feminist issues and children’s issues (Burman Citation2008). This meeting point involves children’s need for care and women’s traditional role as carers, women’s demand for child-care and the experiences and demands loving and caring (Osgood Citation2012) places on the overwhelmingly female workforce of carers.

Feminist theory posits that the distribution of power within our society is patriarchal, thus favoring and representing values and interests stemming from the experiences of males, while oppressing and excluding the values and interests stemming from the experiences of the female half of the population (Haslanger, Tuana, and O'Connor Citation2015). Knowledge distributed through education can therefore also be said to respond to interests and values relating to the experiences of the male population while excluding interests that are associated with female experiences (Grasswick Citation2016). Through the knowledge transmitted through curriculum frameworks, politicians as representatives for the State define what knowledge has relevance and legitimacy for the field. In the case of Norway, the sector’s growth was spearheaded by Minister of Research and Education Kristin Halvorsen and her personal campaign promise to ensure universal ECEC for children between the ages of one and five years in an effort to secure equal opportunities for women in the workplace. The simultaneous effort to secure equal opportunity for women, while also downplaying the role of care in ECEC and women’s work in ECEC presents one of many paradoxes that appear in the crossroads of feminist issues and children’s issues.

It can be said that the feminist demand for equal opportunity found a willing partner in the Norwegian government, who understood the economic ramifications of supporting women in the workplace. Universal ECEC has been an economic success for Norway and led to the unintended consequence of what might be called neoliberal colonization of the feminist agenda (Fraser Citation2013). The government estimated that one crown invested in ECEC gives three crowns return (Aslanian Citation2020). The growth of the ECEC sector in Norway can thus be understood as both a feminist project, driven by the quest for equal opportunity to choose what type of work women wanted to perform and what kind of labor they chose to contribute to society, and a neoliberal project, driven by the drive for economic growth. I draw on the figure of a concubine to loosen up this knot of feminist and neoliberal interests, children’s interests and the fundamental need all life forms have for care.

Methodology

To explore care speculatively, I use the figure of the concubine to activate a ‘plastic reading’ (Malabou Citation2007; Citation2010; Ulmer Citation2015) of the concept. The concept of plasticity draws attention to the inherent mutability of being, whether in the form of texts, ideas, concepts or issues. The concept of plasticity directs attention to the hidden potential and possibilities latent in all things, and insists on a responsible attitude toward how one contributes to the shaping of one’s self and the ideas and issues that shape the world (Malabou Citation2008). Malabou draws on a number of theorists, including Hegel’s concept of the plastic subject (Malabou Citation2005), recent discoveries pointing toward biological and neuronal plasticity within the field of neuroscience (Malabou Citation2008) and Heidegger’s concept of change as characteristic of being (Malabou Citation2011). Applying plasticity to text, Malabou (Citation2007, 439) extends Derrida’s de-construction to activate the ‘something other than writing in writing’, that can transform a given text into a new shape, as a new environment will produce a different phenome, the expression of a genome that changes in subtle and consequential ways. The concept of plasticity emphasizes text as an aspect of being and being as pregnant with possibility and always able to be read otherwise, and to become otherwise (Malabou Citation2011).

A plastic reading, therefore, tries to read a text or concept in a new way, but by way of what is already present in the concept. Malabou re-read Hegel through the concept of plasticity, as well as Heidegger’s concepts of change, mutability and transformation. Each time, Malabou expanded the ideas in new directions through her activation of plasticity. In my activation of a plastic reading of care in ECEC, I read the concept of care through the figure of the concubine and White Papers, media and historical research on care, including Tronto’s care-ethics (Fisher and Tronto Citation1990; Tronto Citation1993; Citation2015a) to activate aspects of the subject matter that are latent, but unexplored and that otherwise could remain dormant. Peering into the paradox of the absence of care in policy and its assumed presence in practice, I find the image of the concubine. Embracing plasticity, in this article the concubine acts as a figure over and through which to stretch the concept of care and the primacy and invisibility of care labor in ECEC.

The concubine figure

The image of the concubine rouses certain unarticulated and ambiguous aspects of care and care-workers, such as servitude/ vicarious power, compulsion/exclusion and invisibility/intimacy. Care-work involves unacknowledged proximity that affects children, families and politicians in equal measure. Someone, somewhere in order for anything in the home or society to be accomplished, must do care-work (Puig de la Bellacasa Citation2017). The primacy of care renders it the most powerful force in our society- and care-workers the most necessary.

In calling upon the image of a concubine, I draw on the concubine as a producer of the valuable commodity of care, secluded from society and unacknowledged for their contributions. The concubine also contributes to reproduction, and thus supplies the need to continue caring. Over 90% of the workforce of ECEC centres are women, so that the women who care for children, have also birthed the children, though they usually do not care for their own children during ‘business hours’. Concubines throughout history have participated in the households and the economies of families and states, having great but unrecognized and only vicarious power (Mack Citation2006). I recognize that concubines have been and are actual people whose bodily experiences and lives are far more complex and reach far beyond those aspects I draw on in this paper. I humbly draw upon their labor in this article to discuss the unrecognized and far-reaching power of care and care-workers.

I will now consider Tronto’s (Citation1993, Citation1998, Citation2015b) feminist perspective on care with the image of a concubine – as a secured, but not explicitly valued commodity in society, before exploring the secluded positioning of care in ECTE policy development through the image of the concubine. Finally, I consider how through stretching the boundaries of care we can begin to explore how the figure of the concubine sheds new light on care in ECTE.

Care-ethics and moral boundaries of care

Disenfranchised by virtue of their slave status (…) concubines used the system in the only way they could, by working within their immediate environment for the betterment of a larger social order in which they could thrive vicariously. (Mack Citation2006, 219)

Internationally, the field of ECEC is in an unprecedented period of growth, fueled by changing socio-economic patterns that encourage both parents to engage in paid work, and supported by a growing body of evidence from the field of neuroscience about the vital role of love in the early years for children’s development (UNICEF Citation2008). Most children in Norway between one and five years old spend their days in ECEC centers, and those under three account for a third of the ECEC population. Though men are actively recruited to work in ECEC centers in Norway, women in Norway along with their international counterparts (Van Laere etal. Citation2014) continue to account for over 90 percent of all ECEC personnel (Statistics Norway Citation2020).

Women have long been understood as ‘natural’ caretakers (Ailwood Citation2007), making the question of what care is or can be a non-issue in ECTE (Aslanian Citation2020). In order to expand on the traditional and conceptually limiting mother–child model, Fisher and Tronto (Citation1990) put forth a feminist theory of caring that approaches care as a situated process rather than particular types of acts carried out by particular types of people. Fisher and Tronto (Citation1990) describe care as a species activity that includes the human and other-than-human environment and actions performed outside of subject-object care relations, viewing care as ‘a species activity that includes everything we do to maintain, continue, and repair our “world” so that we can live in it as well as possible’ (Fisher and Tronto Citation1990, 40). Fisher and Tronto’s (Citation1990) model underlines the contextually situated nature of professional caring practices in ECEC centers. Care practices include dyadic relationships that are a part of a specific material environment – a professional, institutional and pedagogic environment. From this perspective, caring dyadic relationships in ECEC are not the same as those that occur in homes but include other actors and agents beyond dyadic care relationships, such as local and national politics, institutional materiality and the families of children who attend ECEC. Care in ECEC also involves the decisions made and acts performed beyond the dyadic relationship of child- caregiver. Such practices can include the teachers’ planning and cooperation with coworkers, the attention to the organization of the center and pedagogic activities. Additionally, laws and regulations are part of a caring practice when they protect the material necessities of a caring practice, such as ensuring enough, qualified teachers, enough space, enough materials, enough freedom or enough time (Fisher and Tronto Citation1990; Tronto Citation1998). From this perspective on care, all stakeholders share in the responsibility to care, including politicians, rather than care being something assumed and left to ‘others’ to do ‘naturally’.

Researchers are increasingly calling on a care-ethics approach to ECEC that emphasizes the centrality of compassion and relationships, and a relational rather than justice-oriented ethics (Archer Citation2017; Taggart Citation2016). Justice-oriented ethics are built on rendering universal particular views of right and wrong, and applying them to individuals in a variety of situations and relations, whereas relational ethics are built on taking account of specific ethical relationships in varied situations (Botes Citation2000). Fisher and Tronto (Citation1990) use the example of a mother who puts dinner in the oven and leaves her children alone in a house while she works a second job to keep a roof over the family’s head. A justice-oriented ethics could argue that the mother was neglectful, leaving children alone with an oven on, while relational ethics could argue that in the family’s situation, the mother acted ethically, providing food and shelter for herself and her children. The political and philosophical are important aspects of relational ethics as care-ethics, and key to my argument for care as a concubine. A central aspect of Tronto’s (Citation1993) care-ethics, is that care is erroneously understood as distinct from the political realm in part because of traditional ideas about women and the professional realm that act as intellectual boundaries. Perceived moral boundaries act as obstacles to connecting care to the political realm and professionalism, and can provide some explanation for the positioning of care in (or, out of) ECTE policy and what I suggest is a kind of concubinage of care in ECTE.

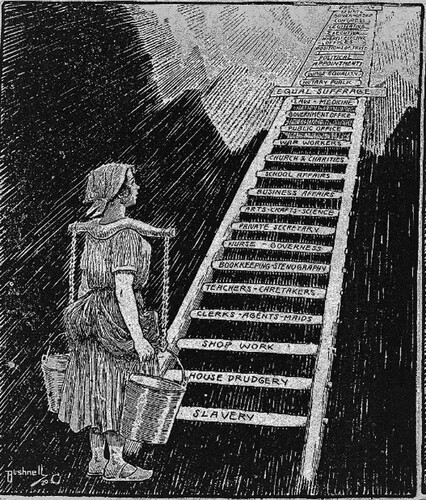

As illustrated in , women and care-work have long been associated with a ‘subordinate status in society’ that Tronto (Citation1993, 63) argues is ‘not inherent in the nature of caring, (…) but is a function of the structure of social values and moral boundaries that inform our current way of life’. Tronto (Citation1993) describes three moral boundaries that keep modern society from perceiving how care could inform political and social practice. The first boundary is the imagined separation of morality and politics. Care is described as lying behind the boundary of politics, because public life is understood in terms of protecting each other’s interests, rather than being a place where we care for each other. The public sphere is based on the concept of autonomy, whilst morality is based on our underlying relation to and interdependence on each other. This perceived boundary, according to Tronto (Citation1993), affects our ability to perceive care as a political concern. Evidence of human vulnerability and interdependence is marginalized, practiced almost subliminally, lest it pose a threat to the image of independence the professional sphere cultivates. The practice of care, like a concubine, is kept behind a discursive boundary that separates care from theory, economy, law and the professional sphere. Moreover, and perhaps most importantly, proximity to the knowledge of human vulnerability and dependency.

Figure 1. The sky is now her limit. Illustration from The Olean New York Evening Herald. New York (Bushnell Citation1920).

The second boundary involves the idea that morality only has a value from a Kantian, ‘moral point of view’, the standpoint of rational, ‘disinterested and disengaged moral actors’ (Tronto Citation1993, 9), rather from a relational, situated pointed of view as described previously. This moral boundary, when applied to care in ECEC, can be recognized in the idea that professional care in ECEC can be understood by applying the same principles as a care between parents and children in the home. There seems to be no need to reassess and understand how caring is produced in ECEC environments, or what complexities are involved.

The third moral boundary Tronto (Citation1993) sheds light on is the conceptual separation between public and private life. Since women have traditionally been situated in the private realm, this boundary serves to contain women’s care practices and care knowledge in the private realm where it has been fostered. Concerns related to care-work traditionally performed by women are thus illegitimate in the public sphere. The proximity of care at the private level seems to compel exclusion at the public level. Tronto argues that these artificial social arrangements must be recognized as such so that we can imagine new ways of organizing society and the place of care in it (Citation1993). Tronto (Citation2015b) refers to care as a democratic responsibility but also refers to the privileged irresponsibility displayed by political actors who do not acknowledge or are not fully aware of the power they hold over other people’s lives. Care as a democratic responsibility demands politicians and others in a position of power over other people and things, including researchers, take the perspective of those who are affected by their actions (Tronto Citation2015b). In order to perceive care as a political and democratic issue, these boundaries must be crossed intellectually. Considering these boundaries through the image of the concubine, the political invisibility of care is a way to keep secluded a provider of sustenance in ECEC. Politicians expect and demand that preschool staff engage in warm, sensitive, caring relations with children while failing to acknowledge care in education policy or consider how their actions affect educators’ ability to care in ECEC. Care is not addressed as an educational or political concern in the Framework for ECTE, but is assumed and required to take place within the walls of ECEC centers. This concubinage of care can partly be explained by moral boundaries that place care in the private realm and prevent stakeholders from intellectually connecting care practices to political and public responsibilities. Care is thus situated in society as natural (Tronto Citation1993), and when considered through a scientific lens, construed narrowly as a dyad-based bond between caregiver and care receiver (Bowlby Citation1965), often a woman and a child. In the next section, I will explore how knowledge about care may affect how and where care can be discussed and how it may be positioned in the policy.

Obscuring care through knowledge

Precisely because royal concubines were the state's main source of both reproductive and agrarian currency, their power had to be checked by patriarchal controls. (Mack Citation2006, 220)

ECTE students learn that knowing how to care involves tacit knowledge (Reinders Citation2010). Polyani (Citation1983) describes tacit knowledge as the result of sensing, doing and experiencing. It can be argued that women generally enjoy a privilege in relation to men as to their life experiences that could serve to afford women a greater store of experience from which to garner tacit knowledge about caring (Gilligan Citation1987). For many women, their role as carers is a biological fact. Women bear children, nurse and most mothers experience the symbiotic relationship of life with an infant wherein each cry, sound and wiggle is subject to mutual interpretation and bodily response. Within the field of psychology, Chodorow (Citation1978) attributes women’s caregiving sensibilities to the fact that girls’ experiences of being mothered differ from boys’ in that girls and mothers share the same sex. Chodorow suggests that girls and their mothers experience a more continuous relationship, while boys and mothers experience a clearer individuation process. This means that, for a girl, the act of individuating occurs simultaneously with the continual act of merging. Practitioners’ personal knowledge of the people they work with in professional practices of care is an important source of professional knowledge that the ability to merge with another enables (Reinders Citation2010). This ‘silent knowledge’ again brings to mind the concubine who’s expertise is needed, but gained in unrecognized ways accomplished through hidden and unspoken practices, apparent through the flourishing of society, but also invisible to society.

Since the mid-1950’s, science has been culminating theoretical knowledge about love as care and its role in human development (Bowlby Citation1952, Citation1965; Harlow Citation1958, Citation1971; Noddings Citation1984). The catalyst for the popularization of scientific knowledge about care was, in part the detrimental effects of a lack of maternal care on children’s health due to poverty, war or illness in the 1940s. Children’s suffering became a worldwide health concern, and in 1951, the World Health Organization (WHO) employed psychologist John Bowlby to investigate. Bowlby (Citation1952) found that children suffered physically, mentally and emotionally from being separated from their mothers. Young children who were hospitalized suffered under behaviorist ideas and a focus on hygiene that dominated in the 1940s and resulted in a practice of touching children as little as possible in order to avoid bacterial infection. These practices resulted at times in a 100 percent infant mortality rate in some hospitals where infants were touched as little as possible to avoid infection (Bakwin Citation1942). Bowlby concluded in his work for WHO, that children needed loving maternal care. He continued to study what he called ‘the growth of love’ between mothers and children and formed what today is known as attachment theory, a clinical model of the development of love and care bonds between children and caregivers. It is curious, in light of feminist theories, that with the popularity of attachment theory, the focus was shifted from care as the affective entanglement of parent and child, which Bowlby first focused on as love, to a focus on the development of psychological ‘bonds’ creating ‘attachment’. Thus in order for care and love to be disseminated as knowledge, they have been clothed in terms of psychological development that shifts the focus from situated, here and now affect between child and adult, to the predictable clinical effect of affect. Bowlby’s son Sir Richard Bowlby described scientific convenience as the reason Bowlby moved from love to attachment:

(…) love had too many different meanings for a scientist and later he called the kind of love that children feel for their parents, attachment: children’s attachment to their parents. (Bowlby, 2010 in White Citation2016)

White (Citation2016, 23) suggests that the move from love to attachment

had the unintended consequence of cutting off the discipline of child development (psychiatry, psychology, social work, education) from poetry, literature, religion, music, imagination, nature and the many aspects of children’s lives, experience and feelings where love is a commonly used word.

Another result of Bowlby’s study of children’s need for love that continues to affect women and ECEC practitioners is the linking of mother as primary caretaker and the growth of love (or attachment). During the 1950’s, when Bowlby conducted his studies, women were the unquestioned primary caretakers of infants. Though two-income households and out-of-home care are now the norms in many Western countries, women continue to spend more time caring for children than men (Suh and Folbre Citation2016), both as ECEC practitioners and in homes, contributing to the underlying assumption that care is something that just happens and that women are there to do.

When asked why care was not an important issue for policymakers to consider when drawing up the Framework for ECTE, several explained that they assumed that care was ‘already there’ (Aslanian Citation2020). Such an assumption could be considered what Tronto (Citation2015b) calls privileged irresponsibility. Tronto’s (Citation2015b) privileged irresponsibility refers to the ‘ways in which a majority group fail to acknowledge the exercise of power’,. Through actions, either personal relations or policymaking, we care, or we do not care. The assumption that care is already ‘there’, a private activity between a caretaker and a child renders care invisible in discourses of professionalism in ECEC. The assumption renders not only the professional and political setting in which care takes place in ECEC invisible in discourses of care within ECTE, but also occludes existential aspects of care.

A care paradox

While state concubinage was from the outset a formidable political institution, it has largely been ignored in scholarly accounts of state formational processes … (Nast Citation2004, xix)

The demanded, desired, and productive presence of care in ECEC is not acknowledged or supported in state-implemented ECTE policy but is rather positioned in informal guidelines and expected to be provided by ECEC practitioners, most of whom are women. This situation brings to mind the seclusion of a concubine, who works, lies with and bears children for a man, children who contribute to society but who does not enjoy legal status or acknowledgment of what she provides to society.

The Norwegian government embraced the neoliberal argument put forth by James Heckman (Citation2000) for developing the ECEC sector. Heckman’s team found that children from deprived households who attended high-quality ECEC programs from infancy in the United States had better life outcomes than those who either were cared for at home or experienced an alternative form of unregulated daycare. His research has been used to show that improved outcomes for these children result in national economic gains (Elango etal. Citation2016; Garcia etal. Citation2016). These findings, along with research that revealed the formative quality of the first years of life (Twardosz Citation2012), has empowered the relationship between the feminist and the neoliberal agenda, boosting interest in institutionalized child-care, but not for the sake of equal rights or in the interest of children’s well-being, but because of economic gains that renders the field of political importance (Leira Citation2004). While the government seizes on the fact that ECEC is beneficial for society, it does not dwell on the development of caring relations, recognized only cryptically as the mechanism behind the gains, what makes ECEC effective (Garcia etal. Citation2016). According to Heckman’s team, the quality of interaction between children and their caregivers is the mechanism that determines the quality of the child’s environment, both at home and at ECEC centers. The team consequently refers to the programs children in their study attend as ‘centre-based-care’ (Garcia etal. Citation2016), while the research is, in turn, used to propagate the effectiveness of ‘early childhood education’ (MER Citation2009, 2015–2016).

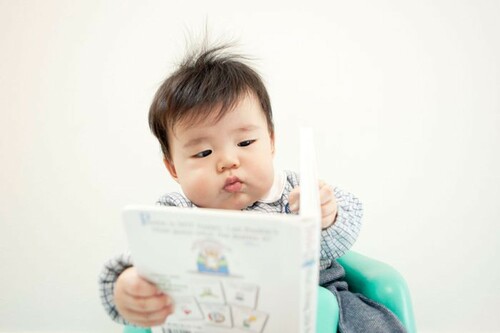

Heckman explains further in an interview that high-quality ECEC is ‘more than a certain staffing ratio or training regimen, (it) is empathetic adults who engage meaningfully with their young charges, giving them personalized attention as they grow and develop’ (Brown Citation2016). Despite the fact that engagement with caring adults is the means by which children benefit, care as the mechanism by which ECEC benefits society is not articulated or seized upon in policy or by media. The image under is one typical image accompanying news articles about Heckman’s research (Ryan Citation2016). Despite Heckman’s findings that quality is related to caring interactions between children and caregivers, ECEC is illustrated as a place where young children receive theoretical knowledge and develop reading skills ().

Figure 2. Starting schooling at eight weeks helps children (Ryan Citation2016; Aikawa and Images Citation2016). Photo: Miho Aikawa/Getty Images.

What I am calling a care paradox in Norwegian ECEC involves the central role of care in ECEC and the lack of interest in developing ECTE policies in response to the centrality of care. An example of the care paradox is visible in the way researchers and the MER analyse and utilize research results. The MER bases its investment in ECEC in part on international research (Sylva et al. Citation2004) affirming that early participation in high-quality ECEC programs that combine education and care has positive outcomes for children’s learning in school and higher education (MER, 2006–2007). Utilized research also asserts that participation in high-quality ECEC has positive economic benefits that extend beyond the individual, amounting to positive national economic outcomes (Heckman Citation2000). Acting on this research, the MER, have linked kindergartens to the public school’s system through a common value foundation and an increased focus on ECEC as a platform for school preparation. The government seizes upon increased learning as the answer to increased quality in ECEC (Nygård Citation2017). A closer look at the research these decisions are based on, however, locates the quality of warm and responsive interactions between educators and children as a particularly important factor in high-quality environments (Sylva et al. Citation2004, 8). Neither the researchers nor the MER discusses the implications for ECTE of caring interactions between educators and children as the mechanism that produces high-quality ECEC.

The aforementioned research project (Sylva et al. Citation2008) shows that children who attended ECEC environments that scored high as intellectual-learning environments produced better social and academic results in elementary school than children who attended ECEC environments that only had high global-quality, which includes the quality of care (social interactions). These results support the MER’s increased focus on the learning environment in ECEC and decreased emphasis on ECEC as a care environment. Whereas ECEC was previously described in policy documents as a care and learning environment, the current Framework (MER Citation2012) refers to ECEC centers only as learning environments. A closer look at the research reveals (personal communication with Kathy Sylva 26, October, 2015) that while some ECEC environments scored high on global quality and low on intellectual learning-quality, there were no environments that scored high on intellectual learning-quality and low on global-quality. In other words, environments that measured high on intellectual learning-quality always also scored high on global-quality. Intellectual learning quality, in other words, builds on quality social-interactions, not vice-versa. I draw a parallel between the way researchers and the MER overlook the role of care when interpreting these research findings and the inadvertent removal of the word ‘care’ from the Norwegian ECTE Framework text.

In the Framework for ECTE produced by the MER (Citation2012), ECEC as a learning environment is elaborated on, but ECEC is not referred to as a care-environment, whilst care is consequently addressed as essential for children in the National Guidlines for ECTE (MER Citation2017) that is written by professionals (mostly women) within the field and not regulatory. While some governmental White Papers also elaborate on the important role of care, and Heckman’s research is used to justify the importance of ECEC (MER Citation2009, 2015–2016), governmental policy documents that address strategy to raise the competency of ECEC teachers do not mention care. These are examples of instances policy makers refer to care in ECEC without using the term care or assigning power to care, nor those who do the caring. Caring is not generally emphasized in policy, portrayed in the media, nor are ECEC teachers required to learn about care or be trained to do or perform care. Despite it not being a legal requirement, the subject of care is a central subject across Norwegian ECTE and the key component of everyday practice. The largely female workforce both in the practice field and within ECTE keeps care knowledge flowing, but are we women also participating in the concubinage of care?

Stretching the boundaries of care

Any concubine son could become king (and many did), and any of their children could be used in political marriages. (Nast Citation2004, xix)

What I have described as the colonization of the feminist agenda by neoliberalism in ECEC has produced the re-location of care-work into professional environments (Sevenhuijsen Citation2003) and at the same time has begun the work of stretching the concept of care. Malabou (Citation2008) emphasizes the connection between our power to shape and be shaped and responsibility. Regarding the question what should we do with our brain? her answer is to resist reproducing and rather consciously shape, think in new ways and act with knowledge of the affect our plasticity has on ourselves and others, human and more than human. Institutionalized care necessitates activation of a plastic understanding of care as more than a maternal or even a parental or human practice, but rather as a professional practice that involves dyads that do not consist of mothers and children in the home, but professionals and children. Moreover, professional adults and unprofessional children practice care in a political, institutional, pedagogic environment.

Stretching care further, we can even detach it from its imagined human root. Puig de la Bellacasa (Citation2017) emphasizes care as the underlying process of nurturance occurring wherever lifeforms flourish. Drawing the concept of care beyond the human, care as concubine suggests a desire to create an illusion of control over what we need most and existential awareness of our human vulnerability. Understanding care as plastic and produced beyond dyads, in and with particular places and with particular things, necessitates the acknowledgement of the interwoven nature of dyadic care and material-discursive contexts as sites of mutual survival. Care, in this sense, underlies existence (Heidegger Citation1962).

Reading care with plasticity and the figure of the concubine also reveals the realities of the bodily production of care, which includes care-work as strenuous, physically and emotionally demanding and for some, debilitating (Pettersen Citation2008). Our human vulnerability is revealed when the concubine’s struggles are visible. Can identifying care-work beyond the dyad and the imagined ‘natural’ act of caring (Aslanian Citation2020), contribute to making the value of care-work visible? Or is the power ‘care’ wields too much of a threat to the neoliberal need for control and accountability? Can practitioners and policymakers acting within the global education reform movement acknowledge the impossible to control, life-supporting power of care and care as the primary need and mechanism behind development and learning in early childhood?

Perhaps care will always elude policy. Perhaps the concubinage of care secures the freedom of care to develop outside of prescribed regulations. In this article, the image of the concubine was drawn on to activate a plastic reading of the politically unarticulated yet foundational and generative role of care in ECEC and its secondary position to ECTE policy. Care is, so to speak, the bed partner of any politician wanting to get things done – because to get anything done, someone, somewhere, needs to care (Puig de la Bellacasa Citation2017). The gendered perception of care and the traditions of law making and caregiving in many ways meet in ECEC and ECTE Framework policy. Women dominate the ECEC workplace, in which care is performed professionally, though care is not included as a learning, competence or skill goal for ECTE. A human, dyadic conceptualization of care relies on the prototype of the parent–child relation and renders the concept devoid of context beyond the dyad. An exclusively dyadic understanding of care limits the development of a concept of care as knowledge in the human and nonhuman, institutional, pedagogic and professional environment of ECEC.

At the same time, children are dependent on human dyadic care relations to flourish and thrive. Malabou's (Citation2005, Citation2007, Citation2008, Citation2010) concept of plasticity and a care-ethics perspective encourage researchers to stretch the boundaries of how care can be perceived in ECEC, emphasizing care as a situated process that is shaped by everyone and everything. This mutuality reveals care as an intimate and existential practice that involves and evokes human and non-human vulnerability. The figure of care as concubine has shed light on the complex and powerful relationship between feminism, neoliberalism, children’s needs and the human and even earthly need for care. Viewing care as concubine reveals care as an existential human need, as uncontrollable and as the mechanism through which economies may grow, offering new ways to understand the positioning of care in ECEC practice and policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Teresa K. Aslanian

Teresa K. Aslanian is a trained early childhood educator and Associate Professor of early childhood education in the Department of Educational Sciences at University of South-Eastern Norway. American by birth, she has lived in Norway for 25 years and published on the subjects of care, love and learning with examples and inspiration from Norwegian kindergartens. Her work utilizes and engages with critical and posthuman perspectives to find new ways of understanding common concepts and themes in ECEC.

References

- Aasland, T. 2010. “Minister of Education and Research Tora Aaslands speech at the introduction of the evaluation of early childhood teacher education institutions, Oslo 20.” September 2010. regjeringen.no

- Aikawa, M., and Images, G. (2016). “Starting Schooling at 8 Weeks Helps Children.” http://nymag.com/thecut/2016/12/james-heckman-says-public-preschool-school-start-at-birth.html.

- Ailwood, J. 2007. “Mothers, Teachers, Maternalism and Early Childhood Education and Care: Some Historical Connections.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 8 (2): 157–165.

- Ailwood, J. 2020. “Care: Cartographies of Power and Politics in ECEC.” Global Studies of Childhood 10 (4): 339–346. doi:10.1177/2043610620977494.

- Archer, N. 2017. “Where is the Ethic of Care in Early Childhood Summative Assessment?” Global Studies of Childhood 7 (4): 357–368.

- Aslanian, T. K. 2020. “Remove ‘Care’ and Stir: Modernizing Early Childhood Teacher Education in Norway.” Journal of Education Policy 35 (4): 485–502. doi:10.1080/02680939.2018.1555648.

- Baines, Donna, Ian Cunningham, Innocentia Kgaphola, and Senzelwe Mthembu. 2020. “Nonprofit Care Work as Social Glue: Creating and Sustaining Social Reproduction in the Context of Austerity/Late Neoliberalism.” Affilia 35 (4): 449–465. doi:10.1177/0886109920906787.

- Bakwin, H. 1942. “Loneliness in Infants.” American Journal of Diseases of Children 63 (1): 30–40.

- Botes, A. 2000. “A Comparison Between the Ethics of Justice and the Ethics of Care.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 32 (5): 1071–1075. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01576.x.

- Bowlby, J. 1952. Maternal Care and Mental Health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Bowlby, J. 1965. Child Care and the Growth of Love. Aylesbury: Pelican books. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WPcNoGl1Lkw&list=PL1BA50B1137D450D8&index=3.

- Brown, E. 2016. “A Nobel Prize winner says public preschool programs should start at birth.” Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/a-nobel-prize-winner-says-public-preschool-programs-should-start-at-birth/2016/12/11/2576a1ee-be91-11e6-94ac-3d324840106c_story.html?utm_term=.b1c20e1a1b29.

- Burman, E. 2008. “Beyond ‘Women vs. Children’ or ‘Women andChildren’: Engendering Childhood and Reformulating Motherhood.” The International Journal of Children's Rights 16 (2): 177–194. doi:10.1163/157181808X301773.

- Bushnell, E. A. 1920. The Sky is now Her Limit. Print. https://npg.si.edu/exhibition/votes-for-women.

- Chodorow, N. 1978. The Reproduction of Mothering. University of California Press.

- Elango, S., J. L. Garcia, J. J. Heckman, and A. Hojman. 2016. “Early Childhood Education.” In Economics of Means-tested Transfer Programs in the United States, edited by R. A. Moffitt, Volume II, 235–297. Chicago. IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Fisher, B., and J. Tronto. 1990. “Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring.” In Circles of Care: Work & Identity in Women's Lives, edited by E. Abel and M. Nelson, 36–54. New York, NY: SUNY Press.

- Folbre, N., and J. A. Nelson. 2000. “For Love or Money—or Both?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14 (4): 123–140.

- Fraser, N. 2013. Fortunes of Feminism : From State-managed Capitalism to Neoliberal Crisis. Brooklyn, NY: Verso.

- Garcia, J. L., J. J. Heckman, D. E. Leaf, and M. J. Prados. 2016. The Life-cycle Benefits of an Influential Early Childhood Program. Cambridge, Mass: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Gerhardt, S. 2004. Why Love Matters. NewYork, NY: Brunner-Routledge.

- Gilligan, C. 1987. “Women's Place in Man's Life Cycle.” In Feminism and Methodology, edited by S. Harding, 57–73. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

- Grasswick, H. 2016. “Feminist Social Epistemology.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by E. N. Zalta. Stanford, CA: The Metaphysics Research Lab. <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/feminist-socialepistemology/>

- Harlow, H. F. 1958. “The Nature of Love.” American Psychologist 13 (12): 673–685.

- Harlow, H. F. 1971. Learning to Love. Stanford, CA: Albion.

- Haslanger, S., N. Tuana, and P. O'Connor. 2015. “Topics in Feminism.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by E. N. Zalta. Stanford, CA: The Metaphysics Research Lab. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2015/entries/feminism-topics/.

- Heckman, J. J. 2000. “Policies to Foster Human Capital.” Research in Economics 54 (1): 3–56.

- Heidegger, M. 1962. Being and Time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). NewYork, NY: Harper & Row

- Langford, R. 2019. Theorizing Feminist Ethics of Care in Early Childhood Practice: Possibilities and Dangers. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Leira, A. 2004. “Omsorgsstaten og familien.” In Velferdstaten og familien. Utfordringer og dilemmaer, edited by A. L. Ellingsæther and A. Leira, 67–99. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Løvås, M. T. 2018. #Uforsvarlig: – Vi må holde oppe trøkket - for barnas skyld. Barnehageno. https://www.barnehage.no/barnehageoppror-2018-bemanningsnorm-foreldreopproret-2018/uforsvarlig--vi-ma-holde-oppe-trokket---for-barnas-skyld/128829?msclkid=7bae22a1af8411ec8641d3a8368a830a

- Lynch, K. 2007. “Love Labour as a Distinct and Non-commodifiable Form of Care Labour.” The Sociological Review 55 (3): 550–570. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2007.00714.x.

- Mack, B. B. 2006. “Concubines and Power: Five Hundered Years in a Northern Nigerian Palace.” African Studies Review 49 (2): 219–220.

- Malabou, C. 2005. The Future of Hegel: Plasticity, Temporality, Dialectic. NewYork, NY: Routledge.

- Malabou, C. 2007. “The End of Writing? Grammatology and Plasticity.” The European Legacy 12 (4): 431–441.

- Malabou, C. 2008. What Should We Do with Our Brain? (S. Rand, Trans.). NewYork, NY: Forham University Press

- Malabou, C. 2010. Plasticity at the Dusk of Writing: Dialectic, Destruction, Deconstruction. NewYork, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Malabou, C. 2011. The Heidegger Change: On the Fantastic in Philosophy. Albany: State University of NewYork Press.

- MER. 2009. “St.melding nr. 41 Kvalitet i barnehagen (Quality in kindergarten).” https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/78fde92c225840f68bce2ac2715b3def/no/pdfs/stm200820090041000dddpdfs.pdf.

- MER. 2011. “Rammeplan for barnehagens innhold og oppgaver (Framework plan for the content and tasks of kindergartens).” https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/barnehage/rammeplan/rammeplan-for-barnehagen-bokmal2017.pdf.

- MER. 2012. “Nasjonal forskrift om barnehagelærerutdanning (National guidelines for kindergarten teacher education).” https://www.uhr.no/_f/p1/i8dd41933-bff1-433c-a82c-2110165de29d/blu-nasjonale-retningslinjer-ferdig-godkjent.pdf.

- MER. 2017. “National guidelines for early childhood teacher education.” https://www.uhr.no/_f/p1/i8dd41933-bff1-433c-a82c-2110165de29d/blu-nasjonale-retningslinjer-ferdig-godkjent.pdf.

- Moss, P., J. Boddy, and C. Cameron. 2006. “Care Work, Present and Future: Introduction.” In Care Work: Present and Future, edited by P. Moss, J. Boddy, and C. Cameron, 3–17. London: Routledge.

- Myers, C. Y., R. L. Hostler, and J. Hughes. 2017. ““What Does it Mean to Care?” Collaborative Images of Care Within an Early Years Center.” Global Studies of Childhood 7 (4): 369–372. doi:10.1177/2043610617749031.

- Nast, H. J. 2004. Concubines and Power. Five Hundred Years in a Northern Nigerian Palace. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Noddings, N. 1984. Caring. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- NOU. 2007. “Formål for framtida.Formål for barnehagen og opplæringen.” https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kd/hoeringsdok/2007/200703160/nou_2007_6.pdf.

- Nygård, M. 2017. “The Norwegian Early Childhood Education and Care Institution as a Learning Arena: Autonomy and Positioning of the Pedagogic Recontextualising Field with the Increase in State Control of ECEC Content.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 3 (3): 230–240.

- Osgood, J. 2012. Narratives from the Nursery. NewYork, NY: Routledge.

- Pettersen, T. 2008. Comprehending Care: Problems and Possibilities in the Ethics of Care. London: Lexington Books.

- Polyani, M. 1983. The Tacit Dimension. Gloucester, Mass: Peter Smith.

- Puig de la Bellacasa, M. 2017. Matters of Care. Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ringsmose, C. 2017. "Global Education Reform Movement: Challenge to Nordic Childhood." Global Education Review 4 (2).

- Reinders, H. 2010. “The Importance of Tacit Knowledge in Practices of Care.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 54 (1): 28–37.

- Ryan, L. 2016. “Public Preschool Education That Starts at Birth Would Be Better for the Economy, According to New Research.” NYMAG. http://nymag.com/thecut/2016/12/james-heckman-says-public-preschool-school-start-at-birth.html.

- Sevenhuijsen, S. 2003. “The Place of Care: The Relevance of the Feminist Ethic of Care for Social Policy.” Feminist Theory 4 (2): 179–197. doi:10.1177/14647001030042006.

- Singer, T., & Lamm, C. 2009. “The Social Neuroscience of Empathy.” In The Year in Cognitive Neuroscience 2009: Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. New York Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04418.x.

- Statistics Norway. 2020. “Barnehager, 2019, endelige tall.” https://www.ssb.no/barnehager.

- Suh, J., and N. Folbre. 2016. “Valuing Unpaid Child Care in the U.S.: A Prototype Satellite Account Using the American Time Use Survey.” Review of Income and Wealth 62 (4): 668–684. doi:10.1111/roiw.12193.

- Sylva, K., E. C. Melhuish, P. Sammons, I. Siraj-Blatchford, and B. Taggart. 2004. The Effective Provision of Pre-school Education (EPPE) Project: Final Report. A Longitudinal Study Funded by the DfES 1997—2004.

- Sylva, K., E. Melhuish, P. Sammons, I. Siraj-Blatchford, and B. Taggart. 2008. Effective Pre-school and Primary Education 3-11 Project (EPPE 3-11) Final Report from the Primary Phase: Pre-school, School and Family Influences on Children’s Development During Key Stage 2 (Age 7-11).

- Taggart, G. 2016. “Compassionate Pedagogy: The Ethics of Care in Early Childhood Professionalism.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 24 (2): 173–185.

- Tronto, J. 1993. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. NewYork, NY: Routledge.

- Tronto, J. 1998. “An Ethic of Care.” Generations 22 (3): 15. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=1281388&site=ehost-live

- Tronto, J. 2015a. “Interview Joan Tronto, Surrey 2015, International Care Ethics Observatory/Interviewer: V.Baur.” ZorgEthiek.nu.

- Tronto, J. 2015b. “Democratic Caring and Global Care Responsibilities.” In Ethics of Care: Critical Advances in International Perspectives, edited by M. Barnes, T. Branelly, L. Ward, and N. Ward, 21–30. Chicago, IL: Policy Press.

- Twardosz, S. 2012. “Effects of Experience on the Brain: The Role of Neuroscience in Early Development and Education.” Early Education & Development 23 (1): 96–119. doi:10.1080/10409289.2011.613735.

- Ulmer, J. B. 2015. “Plasticity: A new Materialist Approach to Policy and Methodology.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 47 (10): 1096–1109. doi:10.1080/00131857.2015.1032188.

- UNICEF. 2008. “The child care transition,” Innocenti Report Card 8.UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/rc8_eng.pdf.

- Van Laere, K., M. Vandenbroeck, G. Roets, and J. Peeters. 2014. “Challenging the Feminisation of the Workforce: Rethinking the Mind–body Dualism in Early Childhood Education and Care.” Gender and Education 26 (3): 232–245. doi:10.1080/09540253.2014.901721.

- White, K. 2016. “The Growth of Love.” Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care 15: 3.