ABSTRACT

Universities are increasingly recognized as spaces and cultures where gendered and sexualized harassment is endemic. This article pays close attention to the manifestations of sexualized behaviours in a campus university in the UK, examining some of the ways in which formations of masculinity are encouraged and reproduced through university structures, processes and aesthetics. The discussion draws on data generated by a creative project utilizing film-based materials as a prompt for collaborative reflections. Bringing together staff and students from across the university in a creative space enabled diverse experiences to be shared and produced rich and detailed insights across disciplinary and generational differences. The paper argues that such creative interventions are a vital form of feminist pedagogy offering a powerful resource for future work in this increasingly urgent field of study.

Introduction

This article presents findings from a project entitled Virgin Territory/Shut Down at University aiming to generate and sustain creative and critical space for exploring sexual harassment in a university context. Despite increased attention in recent years, including in this journal, research examining sexual cultures of universities remains underdeveloped in relation to the reported (and felt) scale and complexity of the issues (Eyre Citation2000; Phipps and Smith Citation2012; Phipps Citation2020; Jones, Chappell, and Alldred Citation2021). This paper adds its voice to these important and urgent debates by providing empirically informed analysis of some of the ways in which universities provide fertile conditions for sexual harassment to occur. In particular, an exploration of damaging cultures of masculinity amongst students and staff extends existing scholarship on masculinities in higher education (Dempster Citation2011; Phipps Citation2017; Jeffries Citation2020; Jackson and Sundaram Citation2021).

Sexual harassment remains an urgent concern for higher education in the UK and elsewhere (Mirza Citation2015; Phipps Citation2017). In the UK, over the past decade, several research studies and surveys (NUS Citation2010; UUK Citation2016; The Student Room Citation2018) as well as high-profile ‘scandals’ reported widely in the media, have pointed to similar, damning conclusions about the widespread prevalence of sexual abuse (see Bull, Calvert-Lee, and Page Citation2021; Tutchell and Edmonds Citation2020). Alongside wider global and national campaigning such as #metoo and Everyone’s Invited www.everyonesinvited.uk this scholarly and media attention makes it clear that sexual inequality and gendered harassment and violence are not new phenomena although they are perhaps being called out and exposed in new ways. Universities are sites where problems of sexual violence loom large. Campus universities in particular, with a ‘traditional’ (young) population living and socializing together in proximity, have become a focus in the UK media for ‘spectacular’ and shocking news stories.Footnote1 As Jackson and Sundaram (Citation2020, 34) argue, such media coverage works to ‘pathologise a small number of “extreme lads” and render invisible the broader socio-political discourses that normalise sexism and harassment as part of everyday life’. In response to the demands of angry students and staff and the putative concerns of prospective students and their parents, universities are responding with various disciplinary policies, training programmes and pedagogic initiatives. However, reputational risk is keenly felt in the neoliberal educational marketplace, and universities have conflicting incentives to demonstrate their positive community values and intolerance of sexual violence whilst minimalizing if not silencing and invisibilizing negative statistics and stories. This contradictory and complex setting provides the context for interventions such as Virgin Territory/Shut Down at University.

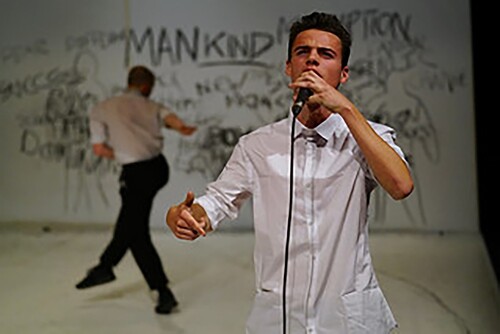

The title of the project, Virgin Territory/Shut Down at University, references two distinct but related live performance and film installations, devised by Vincent Dance Theatre, a UK based international ensemble producing dance theatre with a related social engagement programme.Footnote2 These pieces emerge out of Vincent Dance Theatre’s longstanding commitment to provocative work dealing with difficult issues: in this case, sexualization of young people and sexual abuse and consent, particularly in a digital context. Virgin Territory focuses on the experiences of girls and women, whilst men and masculinities are the focus of Shut Down. They were produced through devised dance theatre involving young women and men, including school-aged young people, whose words appear verbatim in parts of the performances. The live performances were transformed into films. Combining spoken word, dance-performance and a soundtrack, they are powerful and difficult films to watch. Prior to this university collaboration, the films have been utilized as a basis for workshops in schools and colleges, generating discussion and manifesto-like outcomes around young people’s gendered and sexual(ized) lives in twenty-first-century Britain. This project was the first presentation of these materials in a university setting, bringing wider issues of gendered inequalities, sexual harassment and consent into the higher education context.

The analysis here draws on an unusual methodology which – partly by design, party by circumstance – brought university students and staff from across the disciplinary reach of one university into close and meaningful discussion. The project was a collaboration between researchers at a UK university and staff at Vincent Dance Theatre. Fusing research, pedagogy and activism, we present this collaborative project as an example of feminist pedagogy, illustrating the potential of arts as a method for creating spaces where creativity, dialogue and complexity can be generated and nurtured. Megan Boler defines feminist pedagogies as ‘attending to power relations (including those between teacher and student); valuing personal experience and emotion as these inform knowledge and learning; and transforming injustice through reflexive praxis’ (Boler in Boler Citation2016, 21). The following section highlights the ‘affective choreography’ of the workshops and the ways in which combining media, human and non-human intra-actions (Barad Citation2007) offers potential for vital interventions. As well as the clear empirical findings produced through creative collaboration and dialogue, the affective force of masculine posturing, embodiments and expectations was felt in the workshops and the affirmation of these feelings enabled intellectual insights into gendered relations in the university. Such reflexive or indeed diffractive praxis (see Lambert Citation2021) is, we argue, important as part of the more instrumental training and policy-based interventions being developed by many universities (in the UK and beyond) in response to rising visibility and awareness of oppressive and violent sexual cultures across the sector.

As a research strategy, the situated discussion enabled by this project has key strengths. Although universities without doubt provide a ‘conducive context for abuses of power to occur’ (Jackson and Sundaram Citation2020, 119) and there are generalizable features to those contexts across the global field of neoliberal higher education (Phipps Citation2017), a more granular approach enables understanding of nuanced ways in which power inequalities are re/produced and experienced. As a feminist pedagogical project, the workshop sessions on which this discussion draws were themselves interventions aimed at not only understanding but also disrupting existing repertoires and relations of power. Feminist pedagogical interventions privilege experience, emotion and embodiments as ways of knowing; participants learn with and from each other, and with and through different media and matter, attending to multiple intersecting and unequal relations of power and value. Whilst the insights they generate may resonate widely, such discussions are necessarily situated, drawing from and speaking back to their localized contexts. They may be an example of what Alison Phipps (Citation2020, 238) calls ‘speaking in’ about issues of harassment. Rather than speaking out in the media, ‘speaking in’ involves

self critique and experimentation, exploring different ways of being both inside and outside the inquiring space and analysing the systems (intuitional and external) in which inquirers exist. It requires inquirers, especially those in position of power, to speak their minds and open themselves up to others’ thoughts and feelings.

Arts-based methods: from (big) dreams to (small) teams

Brought together by shared concerns about gendered inequities and social justice, a key feature of this collaboration between Cath Lambert and Vincent Dance Theatre is the development of practice-based methods to explore and understand complex relations and experiences through live engagements (Lambert and Vincent Citation2015; Lambert Citation2016; Lambert Citation2018). An ethnographic methodology, using participant observation, interviews and live sociological methods (see Back and Puwar Citation2012; Lambert Citation2018) was planned and full ethical approval granted prior to commencing the project.Footnote4 All names and details as they appear here have been anonymized.Footnote5

Scheduled for delivery in Spring 2020, the shape and trajectory of the project were significantly changed by the Covid-19 pandemic. The project was designed as a large-scale film-based installation. We had booked a large, windowless nightclub in a university Students’ Union. This space has a sticky floor and lingering scent of alcohol, sweat and cleaning products. Its cave-like ambience, its capacious invitation to be creative and collaborative, felt appropriate for both the content and methodology of the project. We imagined the hard-hitting scenes from Virgin Territory, and Shut Down’s black and white masculinity-posturing, loud and arresting on a big screen. We anticipated the mingling of ideas, stories, bodies, participants responding to the films and engaging in creative tasks, writing, drawing, making, using (fake) blood and soil and leaving the imprint of their responses for others to pick up on. And then the pandemic came, and those possibilities were gone. Room bookings undone. Invites cancelled. Plans in suspense (we will wait till we can do it again). Plans in freefall (when will that be?) Plans in rethink and restructure (let’s do it differently, then). What would it mean to reimagine the aims and ambitions of this project in digital form? What losses? (so many) Any gains? (we have to try). Given the timeframe and funder’s remit, this was not a project which we could put on hold or radically rewrite. The only viable option to fulfilling the project in the time available was to translate it into a digital project.

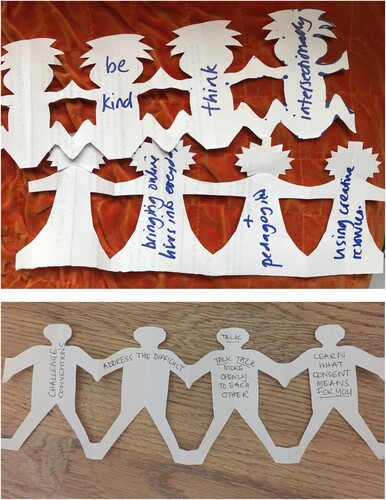

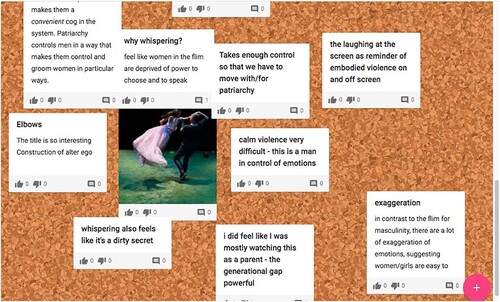

Going digital was a radical departure from the imagined scale, scope and spirit of this project. It was hard to imagine what technologies would allow us to share the primary film resources and enable people to join in and work together in a collaborative way. Would it be possible to retain the aesthetic and affective ambitions for the project? We did not have digital expertise, only the partial, panicky sense of becoming digital experts that any of us working in education or creative arts are now familiar with. Apart from our collaborator at Vincent Dance Theatre, all participants for this project were internal to one university, so we decided to use Microsoft Teams as the platform for which we could, if necessary, access institutional support. We used Padlet as a collaborative space for thinking together – the virtual equivalent of a big sheet of paper on the floor. We ran the project in 6, 2-hour sessions over 4 days. We recruited across the university, targeting Student Union sports and campaigning groups, staff and students working on any of the university’s consent initiatives and anyone with a personal and/or scholarly interest. The call went out via social media, departmental mailing lists, and regular audio-visual features on a big screen on central campus. Each session recruited between 4–6 participants, with a total of 23 participants. They comprised 8 academic and administrative staff and 15 students (9 undergraduates and 6 postgraduates) from across all faculties (12 from Social Sciences, 1 from Humanities and 2 from Science). 19 participants identified as women, 2 as men and 2 as non-binary. During the structured 2-hour sessions, participants were introduced to the making of the films and to the aims of the university-based project. They were then shown selected clips from Virgin Territory and Shut Down, with interactive screen-based activities and focused discussions. The final task involved making paper chains of people (see below) on which we wrote and shared our ‘everyday actions’: a humble and constrained idea relative to the grand mess anticipated in the nightclub space. Discussions were audio recorded and transcribed in an anonymized format and anonymized screen shots were collected throughout the sessions ().

The altered space/time of the activities into this digital format forced a significant rethinking of the project and its possibilities. Space is a key methodological component of Vincent Dance Theatre’s work and of this collaboration. Haunted by the big, open promise of the nightclub and the invite to loosen limbs and imaginations in haptic practice, the space of our individual screens seemed small, and our bodies restrained. Virgin Territory is designed as a multi-screened installation, giving participants the freedom to decide where and when they look, where and when they look away, to shift their bodies and gazes in line with their response to the materials. Online, our orientations are determined. We had to consume the media as it was packaged and delivered. As one participant noted about a difficult scene ‘in live performance we can control where we look but in this format we can’t. The camera controls where we look’.

And yet the online space is multiple in other ways: people bring their domestic settings with them as they hover on the brink between where they sit or stand and the digital space of engagement with others. This brink is full of slippages (sounds, lights, colours, movements) from offline to online worlds. Participants brought some of the vulnerability and exposure of being in their ‘personal’ spaces to the workshops. There was also a real sense that these workshops offered something different to regular online classrooms and meetings. One participant said they signed up because ‘I needed to do something different … to connect with different forms of screen time’. One surprise outcome, which turned out to be a key strength of the project, was the hybrid conversations that emerged. The recruitment and signing-up process resulted in groups where participants of very different status, age and experience were brought together. Each person brought unique expertise, offered different advice to others, and learnt from people with whom we have a university in common but share very little space, time or conversation. We hypothesize that such sustained engagement between people so differently positioned would not have happened in the offline context where people would have gravitated towards familiar and similar others. Finally, although the shift to digital was forced, it felt somehow fitting that we occupied digital space. So much gendered performativity and sexual harassment occur online and via social media. The film materials made graphic how sexual violence is embodied both on and off-line. Today’s young people navigate simultaneously online and offline spaces as (often interconnected) sites of relational encounter (Handyside Citation2021).

We argue here that our use of arts-based methods not only generated important findings, but also destabilized dominant ways of knowing (Lambert Citation2018). The approach we took resonates with exciting theoretical and applied work in the field of feminist posthuman or post qualitative research (Greene Citation2013; Taylor and Bayley Citation2019). Attentive to affective and embodied knowledge-production, the workshops created an assemblage of human and non-human matter in sense-making. They serve as an example of ‘affective choreography’ (Charteris and Nye Citation2019; Youdell and Armstrong Citation2011) the effects of which can exceed the space and time of the interaction. Charteris and Nye (Citation2019, 339) account for their affective choreography as follows:

Pedagogic affect is mobilised

In the hope

That critiques flow

On and percolate

And take lines of flight

Manifestations of masculinity at university

In a film clip from Shut Down, fifteen-year-old Eben’s spoken word performance tells of the damaging manifestations of masculinity as experienced and enacted by boys and men going through different developmental stages of life. The performance provides ‘sketches and outlines of masculinity’ which the actors/dancers try to fill onstage/screen and we, as both audience and workshop participants, were invited to fill and expand in our discussions. The performance highlights expectations that being masculine means being ‘manic’, ‘unmanageable’, treating women ‘like pieces of meat’. Such behaviour disguises teenaged boys’ emotions: he is ‘scared/ his future is shrouded in doubt/ so he smokes, drinks, gets with girls but he’s really just blocking it out’. Moving into his twenties ‘man buckles up and settles down/ the hustle’s up and for some the 9–5 commute bustle comes round/ Straps on a suit/ Becomes the gentleman’. The compelling spoken words and movement over music tells a familiar story of ‘hegemonic masculinity’ (Connell and Messerschmidt Citation2005): aggressively heterosexual, physical, displaying only ‘strong’ emotions and repressing ‘weak’ ones in themselves and others. At every stage of life, a stark binary of gendered expectations in seen to bear down on men and boys.

In the workshops, we discussed ways in which masculinities manifest in the university context and with what effect. Our discussions confirmed findings widely reported in research and media coverage, of a sexualized and misogynistic university culture often fuelled by alcohol (see Dempster Citation2011; Phipps and Young Citation2015; Jeffries Citation2020). Younger students recognized the aggression and bravado on display at flash points in university such as ‘Freshers’ Week’. One male student, Ethan, reflected on club nights at the Students’ Union, where

… most people have had alcohol. There is that expectation of one-night stands from it … It feels like there’s a pressure to fit in, but there really isn’t. But I can see why some people think this is what they are going to have to do.

… amongst us teenagers people do dramatically change, depending on the group they’re with. I have seen boys be one thing then be another and engage in that toxic masculinity, which you probably wouldn’t expect, but I assume there is a pressure to conform.

some of the things that were spoken about as manifesting in that piece I certainly see in both student culture and in staff culture, all the time in different ways, but … you see that what he’s talking about is himself and how he understands it … I’ve understood some of these things as blockages. Thinking of those times where … I’ve felt like I’m engaging in some of that stuff that’s manifesting, and it’s just sort of broken through and you understand what’s under it and a bit more about the person.

Of course, as Rosa suggests above, sexist behaviours are evident in both students and staff cultures. Sara noted that

I have worked for the university for nine years. You see perhaps some of that toxic masculinity with adult staff … People speak through scripts, they’ll say the right things at the right time. They’ll say things that they don’t actually believe. But behind the scenes … you will see that behaviour happen in front of you. It is very difficult to describe, but you will see it, you know, the groups of men will walk with each other, or shout across the office, kind of assert their dominance. The way … they use the space rather differently to how you see women use the space.

Masculine (dress) code: strapping on a suit

Across the diverse workshop discussions, one dominant manifestation of ‘university masculinity’ emerged as ‘suited’, driven by career aspirations and professional expectations. One member of staff, Erika, used the ‘career environment’ as an example:

students are trying to engage with all these Law firms and so on and see whether they would like to work there … There you can see some of the not-so-positive images of masculinity come forward a little in the ways in which male students might sell themselves or portray themselves, kind of the elbowing out of the way … sometimes you have to portray yourself in a certain way.

It’s not limited to just men … Women more often than not now in the neoliberal structures feel [the need] to step into their masculine in the way we perform our duties and the way we present ourselves to the world. There is definitely this tendency of strengthening, of being assertive, being competitive and that’s the way we measure success. And so the fact is that both men and women are being pushed to be masculine and that’s because of the structures, because the structure values these ultra-toxic masculine traits and that’s what we measure success against.

Straps on a suit. Becomes the gentleman

That’s those who make it. Others are trapped in a workforce that remains faceless

to an employer that leaves him virtually payless.

I’ve been in the University for many years. In the Business School I’m particularly struck by the suit. I’m particularly struck by images of masculinity, masculine behaviours, attitudes that I see in women in the Business School as much as I do in men. I’m particularly struck by women’s conformity to some of that when it’s intensely modelled around you … When I think of the student identity or the student journey what might be harder for some students to resist, is the very early professionalisation of our students, who after year one don’t come back through those doors in the same way. So they bring a greater sense of themselves in the first year which I think very quickly evolves because of the professional narrative of what they are aspiring to, and who they are aspiring to [be] … you come in like this, but there’s this narrowing of vision and pathway and possibility.

I watch the way in which they accessorise themselves to become ready … strapping on a suit, it’s uncomfortable. This discomfort that goes with it, then that’s trapped in. And I hear those trappings as well in organisations, the mental health issues that start to surface … into the workplace and industry where some people burn out very quickly because of expectations.

Straight white men at the centre

These astute analyses made by students and staff in the workshops drew attention to a particular form of masculinity nurtured by and within university. Their examples drew on specific disciplinary areas, notably the professional contexts of Law and Business. However, professionalizing behaviours and expectations such as these can be seen in the bureaucratic cultures of university administration (see Acker Citation2012; Erickson, Hanna, and Walker Citation2021) and such insights were also made by Tom, a member of administrative staff:

If you go to get a job in central [administration] … you need to be a straight white male or that’s what they expect to see in the roles … a lot of the people I’ve worked for here – I’ve been in a few different departments – there’s always been like a straight white male who leads the department or who people look to for direction. It always feels really strange, for a place that’s meant to be so diverse.

When I first arrived at [university name] I attended a welcome event … we were sat in this auditorium and there was the Vice Chancellor and the President of the Students’ Union and both were white males sat on the podium in front of us for all to see and I thought to myself … I don’t see myself in these people, and the people sat next to me they look more like me than the people sat in front of us …

When you are able to find yourself in positions of power there is a chance, because you can use that in different ways. But the journey up and towards that … to get close to power, there is a conformity that needs to take place in order to decide when you arrive in those places how you are going to use your power.

Traditional hierarchies intersect with newer evaluative technologies to ensure that people are reckoned up differently. This differentiation may become acutely visible at times of stress – for example, when a sexual harassment allegation is made – when it becomes clear there are some worth more than others.

Interventions

Intervene … it seems so obvious, but it’s absolutely something we should all do isn’t it? (Alex, Senior staff)

What are we modelling in our choice of pedagogy, in our teaching spaces? we play a really critical role in that. What are we creating permission to be? How do we create those spaces where students can come in and be themselves? The risk that’s involved in that … you can’t simply ask of someone to ‘be themselves’. What does that mean? We’re constantly performing versions of ourselves from one context to another.

As women … if we speak out, our language is difficult, we are troublesome and troubling … it will vary from one context to another but … to be different, the courage it takes …

in that patience there is a knowledge and understanding to keep revisiting … even when there’s difficulty or it feels like sometimes you feel you’ve hit a hard place … being able to think ‘how can I find a different way?’ … on a very personal level but also in those public places as an active bystander, finding different ways that you can intervene. It might not be in a verbal [way], it might not be being physically present but finding other ways to intervene.

‘Why whispering?’ wrote one participant on Padlet, followed by the comment that ‘[I] feel like women in the film are deprived of power to choose and to speak’. ‘Whispering also feels like it’s a dirty secret’ responded someone else. We picked the comments up in discussion and there was recognition that whispering could signify repression and silencing, as well as occurring ‘behind people’s back’ as bullying or exclusion. However there were also more positive connotations, such as the solidarity of sharing advice between women that Rae spoke of: ‘the conversation my mum might have had with her friends about ‘I’ve got daughters, how do I prepare them for the world without frightening them?’’ as well as more overtly activist ‘ … women’s whisper networks … [#]metoo, things like that, when women exchange knowledge in like a knowledge underground’.

you might want to speak to your mum about it, your mum might want to speak to you about it … but you can’t quite [trails off] … . currently the disconnect between digital natives and non-natives intergenerationally is an interesting time in history

Such an approach reminds us that careful listening is as important as words and actions. Such careful listening and feeling emerges through affective choreography: the art-based methods we used here generated capacities to hear and sense quiet, uncertain and contradictory knowledges. These knowledges cannot always be expressed or heard, in the usual cognitive, logocentric language of university discourse. In this way, this project offers an example of affective disruption and intervention via feminist pedagogical praxis.

Conclusions

Academia is super masculine … we constantly tear each other down and there’s this sense of competition and we’re always critiquing each others’ work … [we need to] rethink the whole structure of how we do things.

(Erika, member of staff)

The rich discussion generated by this project was enabled by the arts-based collaborative methods utilized. Despite the dramatic shift from in-person to online workshops, the film-clips provided powerful resources for thinking with. Multiple resonances are facilitated by engaging with creative materials that are not didactic but instead invite an emotional response. In this project, students and staff from across different parts of one university took up the affective invitation to respond to the materials and engage in dialogue with each other. The prompts offered by the film materials enabled, we would suggest, different conversations than a more straightforward focus group or interview would have generated. At the same time, the sessions were pedagogical, enacting a form of feminist praxis through emotionally engaged dialogue. Binary conceptions of masculinity and femininity, performatively articulated in Shut Down and Virgin Territory respectively, enabled our participants to begin conversations infused with a tacit acceptance of the problematic nature of this binary and the performative utterances it authorizes. Across all the workshops, we saw no evidence of the individualizing, blaming ‘bad apples’ discourse commonly identified by research in this area. Instead, discussions were characterized by an empathetic, while critical, recognition of structural issues (patriarchy, racism, neoliberalism) and their manifestations in a university context (an over-representation of white men in positions of power, professionalization and competitiveness, inequities in the use of space, laddish and sexist behaviours). The mixed groups, brought together over two hours in an online space, also shaped the discussions in very different ways than individual or more homogenous group discussions would have done. With the source materials in common, participants’ multiple and diverse levels of expertise came to the fore. As we have seen in the extracts selected here, eighteen-year-old undergraduates recognized that their proximity to and understanding of the university’s lad culture or the sexualized use of social media gave them knowledge not shared by older participants, some of whom were seeing the issues very differently though the eyes of teachers and/or parents of teens. Senior managers reflected on their complicities with and resistance to structural pressures to conform and the ways in which ‘seniority’ itself can be utilized as a powerful resource were discussed.

This article offers discussion of findings generated through creative, multi-media workshops. However the focus is not only on ‘findings’; the intense, multi-layered, intra-active workshops also generated affective hybrid spaces in which participants were able to feel and conceptualize masculine logics of power differently. In this way, we suggest that the affective choreography of the workshops themselves intervenes in the fabric of knowledge production with potential to ‘percolate’ (Charteris and Nye Citation2019) beyond the event. Percolation is a slow, humble process, evoking entanglement and co-dependency of materials. Alongside the disciplinary, curricula and training policies and programmes which characterize universities’ responses to sexual harassment, there is an urgent need for different kinds of knowledge generation. The exchanges enabled by this particular methodology, characterized by careful listening, are themselves a form of activism and suggest possibilities for future feminist research and pedagogy that creates spaces for the exchange and entanglement of differently positioned members of the university.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cath Lambert

Cath Lambert is Reader in Sociology at the University of Warwick. Cath’s research activities reflect a longstanding interest in education, gender and sexuality and includes the development of critical, creative and collaborative methods for researching, writing and teaching.

Sian Williams

Sian Williams is Participation & Digital Development Director for Vincent Dance Theatre. Sian leads participation and engagement activities around the company’s creative practice.

Roxanne Douglas

Roxanne Douglas is Teaching Fellow in Gender and Sexuality at the University of Birmingham. She specializes in Arab feminist writing, postcolonial feminism, Gothic studies and zombie fiction.

Notes

2 Further information about both projects can be accessed here https://www.vincentdt.com/productions/.

3 Clip is available to view at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mu9tKQReb6w.

4 Full ethical approval was gained from The University of Warwick Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee, reference HSSREC 18/20-21. On expressing an interest in the project participants were sent full ethical information by email and consent forms were completed and submitted electronically prior to each session.

5 Although in some academic and activist work naming (institutions) is seen as key to accountability, we follow Phipps (Citation2020, 228–229) here in recognizing that the exposing of individual institutions masks the fact that all universities are sites of inequality where harassment and assault occur.

6 In fact, a ‘confessional’ social media app (Lewis and Rushe Citation2014) called Whisper was launched in 2012 where users can anonymously post ‘whispers’, text superimposed over images.

References

- Acker, S. 2010. “Gendered Games in Academic Leadership.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 20 (2): 129–152. doi:10.1080/09620214.2010.503062.

- Acker, S. 2012. “Chairing and Caring: Gendered Dimensions of Leadership in Academe.” Gender and Education 24 (4): 411–428. doi:10.1080/09540253.2011.628927.

- Back, L., and N. Puwar. 2012. eds. Live Methods. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Ball, S. 2012. “Performativity Commodification and Commitment: An I-Spy Guide to the Neoliberal University.” British Journal of Educational Studies 60 (1): 17–28. doi:10.1080/00071005.2011.650940.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. London: Duke University Press.

- Berdahl, J., P. Glick, and M. Cooper. 2018. “How Masculinity Contests Undermine Organizations, and What to Do About It.” Harvard Business Review. November 2. Accessed February 2023. https://hbr.org/2018/11/how-masculinity-contests-undermine-organizations-and-what-to-do-about-it.

- Boler, M. 2016. “Interview with Megan Boler: From ‘Feminist Politics of Emotions’ to the ‘Affective Turn’ Megan Boler and Michalinos Zembylas.” In Methodological Advances in Research on Emotion and Education, edited by M. Zembylas, and P. A. Schutz, 17–30. New York City: Springer International Publishing.

- Bull, A., G. Calvert-Lee, and T. Page. 2021. “Discrimination in the Complaints Process: Introducing the Sector Guidance to Address Staff Sexual Misconduct in UK Higher Education.” Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education 25 (2): 72–77. doi:10.1080/13603108.2020.1823512.

- Bull, A., and S. Oman. 2022. “Joining Up Well-Being and Sexual Misconduct Data and Policy in HE: ‘To Stand in the Gap’ as a Feminist Approach.” The Sociological Review 70 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1177/00380261211049024.

- Butt, G. 2005. Between You and Me: Queer Disclosures in the New York Art World, 1948–1963. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Charteris, J., and A. Nye. 2019. “Posthuman Methodology and Pedagogy: Uneasy Assemblages and Affective Choreographies.” In Posthumanism and Higher Education, edited by C. A. Taylor, and A. Bayley, 329–347. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Connell, R., and J. Messerschmidt. 2005. “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.” Gender and Society 19 (6): 829–859. doi:10.1177/0891243205278639.

- Dempster, S. 2011. “I Drink, Therefore I’m Man: Gender Discourses, Alcohol and the Construction of British Undergraduate Masculinities.” Gender and Education 23 (5): 635–653. doi:10.1080/09540253.2010.527824.

- Erickson, M., P. Hanna, and C. Walker. 2021. “The UK Higher Education Senior Management Survey: A Statactivist Response to Managerialist Governance.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (11): 2134–2151. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1712693.

- Eyre, L. 2000. “The Discursive Framing of Sexual Harassment in a University Community.” Gender and Education 12 (3): 293–307. doi:10.1080/713668301.

- Freeman, E. 2010. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Greene, J. C. 2013. “On Rhizomes, Lines of Flight, Mangles, and Other Assemblages.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 26 (6): 749–758. doi:10.1080/09518398.2013.788763.

- Handyside, S. 2021. “Virtual Potentialities: Teenagers’ Stories About Social Media.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Warwick. Accessed February 2023. http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/156941/.

- Jackson, C., and V. Sundaram. 2020. Understanding ‘Lad Culture’ in Higher Education: A Focus on British Universities. London: Routledge.

- Jackson, C., and V. Sundaram. 2021. “‘I Have a Sense That It's Probably Quite Bad … But Because I Don't See It, I Don't Know’: Staff Perspectives on ‘Lad Culture’ in Higher Education.” Gender and Education 33 (4): 435–450. doi:10.1080/09540253.2018.1501006.

- Jeffries, M. 2020. “‘Is It Okay to Go Out on the Pull Without It Being Nasty?’: Lads’ Performance of lad Culture.” Gender and Education 32 (7): 908–925. doi:10.1080/09540253.2019.1594706.

- Jones, C., A. Chappell, and P. Alldred. 2021. “Feminist Education for University Staff Responding to Disclosures of Sexual Violence: A Critique of the Dominant Model of Staff Development.” Gender and Education 33 (2): 121–137. doi:10.1080/09540253.2019.1649639.

- Lambert, C. 2016. “The Affective Work of art: An Ethnographic Study of Brian Lobel’s Fun with Cancer Patients.” The Sociological Review 64 (4): 929–950. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12394.

- Lambert, C. 2018. The Live Art of Sociology. London: Routledge.

- Lambert, L. 2021. “Diffraction as an Otherwise Practice of Exploring new Teachers’ Entanglements in Time and Space.” Professional Development in Education 47 (2-3): 421–435. doi:10.1080/19415257.2021.1884587.

- Lambert, C., and C. Vincent. 2015. “Dance as Method?: The Possibilities for Developing Embodied, Sensory, Live and Practice-Based Methods and Methodologies.” Warwick Arts Centre, 12 March. Audio recording. Accessed February 2023. https://www.vincentdt.com/project/embodied-methodologies/.

- Lewis, P., and D. Rushe. 2014. “Revealed: How Whisper App Tracks ‘Anonymous’ Users.” The Guardian, 16 October. Accessed February 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/16/-sp-revealed-whisper-app-tracking-users.

- McDowell, L. 2014. “The Sexual Contract, Youth Masculinity and the Uncertain Promise of Waged Work in Austerity Britain.” Australian Feminist Studies 29 (79): 31–49. doi:10.1080/08164649.2014.901281.

- Mirza, H. 2015. “Sexual Harassment: Moving from Shame to Action or How to Make the Personal Political.” Accessed February 2023. https://shhegoldsmiths.wordpress.com/shame-and-sexual-harassment/.

- Morley, L. 2013. “The Rules of the Game: Women and the Leaderist Turn in Higher Education.” Gender and Education 25 (1): 116–131. doi:10.1080/09540253.2012.740888.

- National Union of Students. 2010. Hidden Marks: A Study of Women Students’ Experiences of Harassment, Stalking, Violence and Sexual Assault. London: NUS.

- Phipps, A. 2017. “(Re)Theorising Laddish Masculinities in Higher Education.” Gender and Education 29 (7): 815–830. doi:10.1080/09540253.2016.1171298.

- Phipps, A. 2020. “Reckoning up: Sexual Harassment and Violence in the Neoliberal University.” Gender and Education 32 (2): 227–243. doi:10.1080/09540253.2018.1482413.

- Phipps, A., and G. Smith. 2012. “Violence Against Women Students in the UK: Time to Take Action.” Gender and Education 24 (4): 357–373. doi:10.1080/09540253.2011.628928.

- Phipps, A., and I. Young. 2015. “‘Lad Culture’ in Higher Education: Agency in the Sexualization Debates.” Sexualities 18 (4): 459–479. doi:10.1177/1363460714550909.

- Puwar, N. 2004. Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place. London: Bloomsbury.

- The Student Room/ Revolt Sexual Assault. 2018. “Sexual Violence at Universities Statistical Report.” Accessed February 2023. https://revoltsexualassault.com.

- Taylor, C. A., and A. Bayley. 2019. Posthumanism and Higher Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tsaousi, C. 2020. “That’s Funny … You Don’t Look Like a Lecturer! Dress and Professional Identity of Female Academics.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (9): 1809–1820. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1637839.

- Tutchell, E., and J. Edmonds. 2020. Unsafe Spaces: Ending Sexual Abuse in Universities. London: Emerald Publishing.

- Universities U K. 2016. “Changing the Culture: Report of the Universities UK Taskforces Examining Violence Against Women, Harassment and Hate Crime Affecting University Students.” Accessed February 2023. https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/what-we-do/policy-and-research/publications/changing-culture.

- Willis, P. 1977. Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids get Working Class Jobs. Farnborough: Saxon House.

- Youdell, D., and F. Armstrong. 2011. “A Politics Beyond Subjects: The Affective Choreographies and Smooth Spaces of Schooling.” Emotional, Space and Society 4 (3): 144–150. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2011.01.002.