ABSTRACT

The Saudi 2030 vision states it is committed to empowering women through education and employment, but the literature scarcely addresses their everyday realities. This paper utilises a critical realist perspective to examine the mechanisms emerging from the interplay of structural and cultural factors that impact women’s empowerment concerning local realities in Saudi Arabia. Situated within a broader study, this research explores the qualitative element of women’s work and education experiences by analysing policy documents and semi-structured interviews. The findings indicate that structure and culture have a diverse impact on education and employment, which may ultimately lead to disempowerment.

Introduction

The Saudi Vision 2030’, introduced in 2016, states that:

Our economy will provide opportunities for everyone – men and women, young and old – so they may contribute to the best of their abilities … One of our most significant assets is our lively and vibrant youth. We will guarantee their skills are developed and properly deployed … Saudi women are yet another great asset. With over 50% of our university graduates being female, we will continue to develop their talents, invest in their productive capabilities, and enable them to strengthen their future and contribute to the development of our society and economy (Saudi Vision Citation2030, Citation2016, 37, emphasis added).

Qatar and Oman’s 2030 vision illuminates education as the leading element to obtaining gender equality and female empowerment (Golkowska Citation2017). Currently, 54.9% of women have enrolled in higher education (HE) in Qatar, with 57.9% being part of the labour force. However, only 15.1% of women hold managerial and senior official positions (Global Gender Gap Report Citation2021). These figures expose the degree to which female education and labour market participation are intertwined within the Arab Gulf.

Findlow (Citation2012) asserts that HE in the Arab Gulf region shapes gender and feminist awareness as it can enable and hinder female empowerment. Through personal experiences of women, the pull between caring for families, and involvement in the labour market, has begun to stretch with individualised economic and political campaigns focused on improving shortfalls in gender equality. The collective voice of the women of the Arab Gulf shares that HE and increased involvement in the workforce is a high priority for female empowerment.

The Saudi vision 2030 expresses the government’s commitment to empowering Saudi women who have long been marginalised under the banner of ultra-conservative traditions and social norms. Traditionally, the Saudi government prohibited women from sharing workspaces with men promoting a social construct that limited women as ‘nurturing mothers’ and ‘good housewives’ (Bao, Ha, and Barnawi Citation2019). KSA’s new economic policy promises to develop women’s talents further by raising their participation rate in the labour market ‘from 17% to 25%’ and helping them ‘build their professional careers’ (Saudi Vision Citation2030, Citation2016, 37). However, when examining recent statistics, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has fallen short of its targeted figures. The statistics show that although women hold a 69.9% enrolment in HE, a small percentage of this cohort accounts for the participating workforce. Furthermore, women receive 24% of the salaries of their male counterparts and only account for 6.8% of managerial and senior official positions (Global Gender Gap Report Citation2021). This reality begs the question of the meaning of gender equality and empowerment in the Saudi context.

Discourses surrounding education, work, and women’s empowerment through increasing educational opportunities, raising participation rates in the labour market, and investing in talents and capabilities are ubiquitous in current global policies of gender empowerment (Kabeer Citation2020; Mohanty Citation2006; Monkman Citation2011). However, these policies rarely explicitly explore the interrelationship between education and work. This interplay can produce mechanisms of disempowerment concerning structural and cultural factors such as the socio-cultural, political, religious, and economic realities faced and experienced by Muslim women in under-represented contexts, such as KSA. Local context, power structures, and various social arrangements are notable hindrances (Bao, Ha, and Barnawi Citation2019).

Policy initiatives related to gender empowerment in Muslim societies, including KSA, are often intertwined with complex social, cultural, religious, and ideological arrangements, such as family responsibilities, parental pressures, and rigid local customs (Alharbi Citation2015). Therefore, explicitly investigating local Muslim women’s experiences to capture the realities they face beyond statistical narratives can sharpen our understanding (Doumato Citation2000). Such investigations demand ‘research that is contextualised, nuanced and grounded locally’ (Monkman Citation2011, 2). Hence, qualitative semi-structured interviews with Saudi women from diverse backgrounds enable exploration regarding how they understand and negotiate their experiences. We sought to understand the educational, workplace, and empowerment experiences in the context of recent policy reforms of a sample of Saudi women from KSU. This investigation considers explicit and implicit socio-cultural, political, economic, and religious elements. To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate disempowerment due to the interplay between education and employment through a critical realist perspective in KSA, contributing to the scholarship of gender and empowerment.

Conceptual framework

Education, employment, and empowerment

Conceptually, education is construed ‘as consisting of a process, action, and an outcome, all of which centre on empowerment’ (Seeberg Citation2011, 44) and is associated with various successful employment opportunities for women (Kabeer Citation2020). Hence, empowerment has been defined, implemented, and appropriated differently in diverse socio-cultural, economic, religious, and political conditions. According to Monkman (Citation2011, 2), ‘development that does not provide opportunities to challenge inequitable social relations (e.g. gender relations) remains a tool of social reproduction, not of social change’. Therefore, we propose that socio-cultural norms, religious and local customs, and political and economic conditions related to the ongoing empowerment process constitute an analytical framework for exploring the complexity of empowerment. This framework moves beyond the basic formula of education, work, and empowerment as an outcome and is implicated in contemporary gender and empowerment policy goals, initiatives, and practices.

Krause (Citation2009) explores the participation of women within government-supported organisations and how they influence societal modifications in terms of gender roles within the job market. Within these contexts, issues surrounding political rights and receiving a second-class status in terms of women’s citizenship persist. In her critique of the Arab Human Development Report (AHDR), Hasso (Citation2009) argues that while the AHDR seeks to redistribute power and create a better system of governance with a focus on female empowerment, the report is politically privileged and operates within a UN framework that strengthens states. Thus, the report disempowered women due to how it conceptualised their issues. Ultimately, they present female participation in the formal job market in the Arabian Gulf as remaining the lowest internationally, with continued disempowerment through temporary work contracts and poor working conditions.

The commitment of the Saudi government to empower women under its new economic policy indicates that equal opportunities promote various socioeconomic positions for women. These prospects include investment in education, raising women’s economic participation, encouraging businesses to help women advance their careers, and promoting financial independence (Saudi Vision Citation2030, Citation2016). The policy’s goals seem promising for Saudi women, but they are similar to previous Saudi initiatives such as the Nitaqat policy. Nevertheless, Nitaqat was merely a form of Saudization, unlike Vision 2030, which seeks to improve women’s labour market participation. Unfortunately, the lack of quality education programs at that time, and academia’s failure to consider labour market needs stalled Nitaqat’s progress.

Furthermore, local employers prefer to hire cheaper labour from other countries, which also became an issue in Nitaqat’s effectiveness. Hence, researchers know little regarding how the idea of empowerment differs from the previous initiatives or how the government negotiates women’s empowerment under the banner of ‘our long-held Islamic principles, Arab values, and national traditions’ (Alshanbri, Khalfan, and Maqsood Citation2015; Saudi Vision Citation2030, Citation2016).

Methodology

Study perspective

This study adopts a critical realist perspective that differentiates the ‘real’ world from the world people can observe, where the ‘real’ world is seen as separate from theories and human interaction (Bhaskar Citation2008). Within this study, this perspective examines the structure, which creates mechanisms that enable or constrain empowerment attained by Saudi women in the context of their educational attainment and the nature of their involvement in the Saudi labour market.

Study area

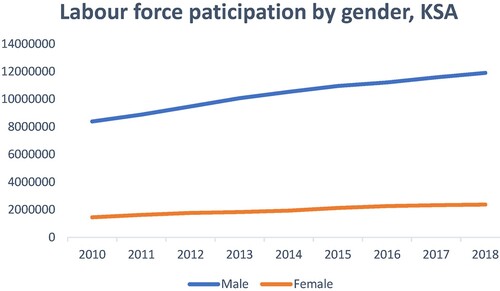

Since the inception of the Saudi Vision 2030, significant efforts have been made to empower women and enable their contribution to the economy. Thus, the Saudi government gave women the right to participate in the labour market without restrictions, with no gender separation in workplaces or discrimination based on the nature of jobs. suggests a rise in Saudi women’s participation rate in the labour market since 2016.

Table 1. Women’s employment trends (2016–2019), adapted from Jawhar et al. (Citation2022).

While the overall growth of women’s participation in the labour market suggests a positive impact of Saudi Vision 2030, the discrepancies between professions and the low involvement of women in some professions invite a more critical qualitative analysis beyond statistics.

depicts men’s and women’s involvement in the labour force between 2010 and 2018, illustrating significant gender differences, with the continuously growing involvement of men.

Figure 1. Labour force participation by gender (2010–2018), adapted from Jawhar et al. (Citation2022).

Method

This qualitative study examined how some Saudi women view the relationship between education, social structures, and labour market participation. Qualitative studies are an appropriate strategy for exploring policy implementation and the associated issues in a real-life context, commonly used in investigating complex phenomena in their multifaceted contextual conditions (Creswell and Poth Citation2016), which is in line with the aims of this study.

Data collection and researchers’ positionalities

The data presented in this study are part of an ongoing research project funded by the Saudi Ministry of Education and governed by King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre (KAIMRC), which issued the research IRP (RJ20/009/J). The project explores the impact of women’s education and participation in the knowledge economy on the Saudi Gross Domestic Product.

15 Saudi women were purposefully sampled and selected from the quantitative element of the aforementioned broader study. Participants were recruited due to their working age and representing a diverse selection of educational backgrounds and socioeconomic statuses (Appendix). The individual semi-structured interviews lasted 45 min to 1 h and were conducted in Arabic. The interviewers (a man, the first author, and a woman, the second author) shared the participants’ social and cultural backgrounds. Taking the position of empathetic listeners allowed researchers to become reflexive during the interviews and encouraged the free sharing of experiences (Creswell and Porth Citation2016). Having a female co-investigator added to the contextual validity of the analysis (Sian et al. Citation2020). Data were inductively analysed to allow various discourses and mechanisms to emerge (Bhaskar Citation2008). The interviews were transcribed and discussed with the participant before employing critical discourse analysis to identify clusters of discourses. We re-examined our interpretation of the data each time a new understanding emerged (Haynes Citation2012). Participants’ responses were translated into English, then checked and verified by four bilingual individuals to ensure meaning and accuracy (Alhawsawi Citation2014). All information obtained from the participants was kept confidential and anonymous through pseudonyms.

Findings and discussion

The analysis findings focused on three main clusters of discourse relating to education, social structure, and gender equality.

Education

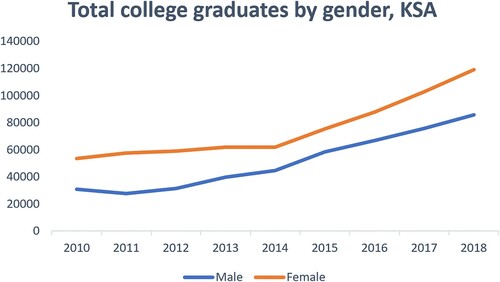

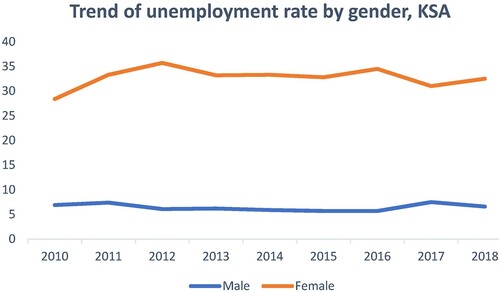

Although the literature shows the profound impact education has on women’s empowerment and their successful participation in the labour market (Kabeer Citation2020), KSA appears to be slightly different (Jawhar et al. Citation2022). There is a higher percentage of women than men graduating from HE, while women’s participation in the labour market does not align with their graduation rate ( and ).

Figure 2. Total college graduates by gender, KSA, adapted from MoE (Citation2020).

Figure 3. Unemployment rate by gender, KSA, adapted from Jawhar et al. (Citation2022).

As of 2021, only 16.4% of women participated in the Saudi job market after graduation (Jawhar et al., Citation2022).

Participants’ answers regarding education could be categorised as addressing the following issues: (1) King Abdullah international scholarship program of 2010, (2) the relevance of education and training provided in Saudi HE, and (3) the importance of the English language.

King Abdullah scholarship program

Among the discourses that emerged from the interview data was the Saudi Ministry of Education Scholarship Program’s influence on female empowerment and labour market participation. The scholarship program encourages Saudi women to pursue graduate education in competitive and international HE institutions, which assists in empowering Saudi women culturally, educationally, and economically (Alsqoor Citation2018). Many of our participants noted the positive influence of the scholarship program. Fareeda, who obtained a master’s degree from an international university, discussed the value of education for employment. However, she attributed this to the context rather than education per se:

I was influenced by how I was able to find the information, not by the information itself. You must research for it there. They turn the information into reality. I saw the machines I had read about and worked on them too.

Everything I studied in my master’s degree is currently used by laboratories in Saudi. I learned these from my degree abroad … Studying there qualified me for employment in the Saudi market.

Fareeda valued the education she received abroad in terms of skills, knowledge, and teaching methods. This is in line with Alsqoor’s (Citation2018) argument that scholarships given to women allow them to be better prepared to participate in the labour market. Conversely, Leen experienced a disappointment that she could not secure employment with her overseas qualification due to a lack of recognition of the degree’s value and the nature of the labour market:

I applied to all the universities in Saudi, and I went everywhere that I could … They all said, ‘Sorry you’re old, we can’t accept you’. … I applied everywhere, without any response.

The relevance of education and training

Pre-graduation internships were a leading aspect of education that influenced women’s participation in the labour market. Evidence suggests that work experience during undergraduate studies increases the chances of employment within four to five years after graduation (Nunley et al. Citation2017). In Saudi undergraduate programs, students are offered internships before graduation. This opportunity aims to provide students with real-life exposure to the local job market with a mind to bridge the gap between theoretical and practical knowledge (Al-Ahmadi Citation2003). However, the participants expressed diverse feelings and reported different experiences regarding the value of pre-graduation training for their current employment status. Samah, a participant with a bachelor’s degree, commented:

I’m a public administration graduate. I was supposed to be provided with training and practicum. There was no practical application up until my graduation … there was nothing … Our education was rooted only in memorisation.

We graduated with mostly theoretical knowledge … Honestly, this college is terrible. It doesn’t even have a thought-out plan … How can a college prepare its graduates for work if it doesn’t know their actual needs?

My participation in the labour market is a result of my competencies. My college education didn’t contribute much. I only wanted a certificate that said, ‘Bachelor’s Degree’. What I studied was theoretical, without any practical experience.

Although it was only for six months, the training was excellent. I changed considerably, thanks to the electric company where I practised. It provided me with all the needed skills and knowledge suited to the profession.

Unlike others, my university provided us with a theoretical background and extensive practice. The labs were utilised effectively. The internship was located in a hospital, and we didn’t have a chance to explore other work environments.

English language competency

Competency in the English language is an element linked to education influencing participation in Saudi’s local labour market. Local communities and the media have criticised the Saudi HE system for producing a workforce with poor English language proficiency for job markets (Barnawi and Al-Hawsawi Citation2017, 206). Barnawi and Al-Hawsawi (Citation2017) argued that ‘employers in leading industries across the country constantly report that Saudi university graduates are good in specific subject knowledge but lacking in workplace skills such critical thinking, collaborative working and communication in English’. Although most Saudi HE institutions did not sufficiently emphasise English, all participants in this study attributed high value to an advanced English competency level, with benefits such as securing employment, career progression, better salary, accessing new knowledge, and realising harmony in the workplace. Samah stated:

The English language has become a requirement, especially in big cities. Most of the population are foreigners; they often communicate in English. I must understand it. Otherwise, my career will be affected … My lack of English fluency has affected me greatly. I can’t get a promotion or better job opportunities with a higher salary … When I look for information related to my career, I usually find it in English.

The English language is very important. You need to prove your English proficiency before you apply for a job … Lacking English proficiency is a disaster because all the work is done in English. You use it to communicate and write reports. The system you use is English. Devices, samples, everything that comes to you, even the patients’ names, are written in English.

Social structure

Societal issues tremendously impact women’s participation in the labour market (Al-Bakr et al. Citation2017; Sian et al. Citation2020). Comparatively, Prager (Citation2020) shares that although the UAE instituted many concessions to increase gender equality, there are numerous cultural hindrances. Barriers such as patriarchal mindsets and the stereotyping of women in terms of value systems are still supported.

The views regarding women’s roles and expectations in KSA are socially constructed and often influenced by the local culture and the Islamic Awakening (Sahwa) political interpretations of Islam (Lacroix Citation2011). Here, women are symbols of family honour, traditional values, and Islamic morality (Doumato Citation2000). Until recently, this forced women to negotiate societal roles in their behaviour continuously (Sian et al. Citation2020). Our findings revealed additional challenges Saudi women face upon graduation, with social views influencing their decisions regarding their university major, the university’s location, and their subsequent workplace.

The role of the family before, during, and after university

The family plays a substantial role in women’s lives in KSA, and their support is vital for female participation in education and the labour market (Alharbi Citation2015). Specific societal issues that influenced women’s decisions emerged from our data regarding their studies’ context and subject matter. Fareeda, who studied science for her undergraduate degree, indicated that science was not her first choice; however, it was the closest discipline to her interests that were available at her hometown university. Being a woman, Fareeda realised that her father would not allow her to study outside her hometown, despite her mother’s support:

Biology was the closest speciality to Medical Science that I wanted to study. the nearest university that offers MS was in Jeddah [400 KM from her hometown] … Mum favoured my travel, but dad opposed it due to the distance, my age, and being a single lady.

I won a scholarship for talented students to study in the UK, but my father refused, adding, ‘Do you think you could go alone to Britain’? I have so much talent and potential, which my family suppressed because I am a girl.

When dad was alive, he used to drive me from the village to the university. The drive was 45–50 min. Every day he drove and waited for me under the bridge in Riyadh’s simmering heat until I had finished, and then he took me home …

I would not have made it if it wasn’t for dad’s support. If he had assigned me to the care of my brother, with whom I fought daily to drive me places, my education would have been limited … My father made me independent …

During undergraduate studies or before marriage, parents are typically the primary decision-makers for daughters. Moreover, the husband and children influence whether a woman will start a career. Leen’s choices were, therefore, limited:

I have a family; being separated from them by working in a different city would deeply impact them. My husband works here, and my children attend school here. I can’t afford to take the children to another city where I have to shoulder the responsibility alone. Besides, I would have taken the risk if jobs at private companies had more security. I may go to work there for a month or two; then they would fire me. This often happens, mostly to women. Maybe it’s OK for an unmarried woman to take the risk, but it’s tough for a married woman …

I have children, and a husband … My husband can’t move anywhere … He doesn’t have great qualifications. It isn’t easy. He is the head of the family. I don’t want to take on his responsibilities; No … I don’t want to carry all the responsibilities of the family … Maybe when he retires, we can move somewhere else. I have narrowed down the scope of my job search because my family is my priority; I don’t want my employment to be at the expense of their well-being … If I weren’t married, I would have gone places and searched for opportunities.

Emirate women have begun to demand the freedom to pursue educational and career goals which they felt could not be obtained once married, such as lack of mobility. Similarly, 60% of Emirate women in the UAE have begun to opt to avoid marriage (Prager Citation2020). James and Shammas (Citation2018) echo this sentiment in that Gulf women often experience pressure from families and spouses not to seek employment after marriage, especially if they have children. Furthermore, Marten (Citation2018) notes that although KSA has broadened women’s possibilities to study in recent years, mechanisms such as family pressure still constrain their agency.

The impact of social perceptions

Saudi societal views regarding women’s roles and careers influence female participation in the labour market (Al-Bakr et al. Citation2017; Sian et al. Citation2020). This reality is rooted in social ties formed by Sahwa traditions and local cultural ideologies (Lacroix Citation2011; Sian et al. Citation2020), including societies’ perceptions of women and women’s perceptions of themselves (Doumato Citation2000). These beliefs influence women’s perseverance in their careers. Samah, a saleswoman, stated:

I am torn between a job that is not financially rewarding, as I cannot even get a bank loan and a society that doesn’t recognise my contribution … I always receive negative comments that break the deepest point of my soul, such as, ‘If you were respectable, you would not work in a mall’, ‘You’re not a decent person’, ‘I wonder how barefaced her family is to allow her to work at a mall’. I return home with the world’s burdens, and my family says, ‘Your work isn’t significant enough to say that you are burdened by it’. This is depressing … It makes me hate my job that offers nothing but a low salary and social isolation.

The social stigma was not limited to sales in a mixed-gender working environment but also environments where people draw gender lines. Leen discussed the perception of women’s departments in a Saudi university:

Although I applied for a job at a university, I was shocked that I couldn’t sign my contract due to the segregation between men and women. They went as far as asking my husband to sign on my behalf … Everything was done on the men’s campus.

By nature, unlike men, women are control freaks. They over-discuss the details before making a decision. Such behaviours cause severe work delays and make working with women managers unbearable.

Gender equality

Gender equality is a topic that has saturated many discussions about women’s participation in the labour market (Kabeer Citation2020). Gender inequality is deeply embedded in Saudi society (Al-Bakr et al. Citation2017; Sian et al. Citation2020; Syed, Ali, and Hennekam Citation2018). In this study, gender and biological roles stood out as structures that impact women’s employment. However, this was associated with social context and surroundings.

Gender and biological roles

The participants in this study reported experiencing gender inequity and its impact on their labour market participation. Mariam stated the following in terms of her experience of gender equality:

Being a woman limited my mobility, particularly during my undergraduate training. I couldn’t drive myself; I didn’t have a driver. My brother could drive himself and got the training and experience that enabled him to obtain his desired job …

My sister was repeatedly denied employment once she declared she was married with a child. They always hint that they prefer single women with no family. I was fine until I was engaged, then the gates to hell opened. They moved me from one branch to another, changed my shifts, kept me late at work, and cut my salary unlawfully. I ended up in a position where I had to quit.

The principal of my [private] school once said, ‘Please, no pregnancy next year. We cannot afford people going on maternity leave’. This is illegal! We disputed it at the labour office but couldn’t prove it. It is a known hidden culture that can’t be proven.

Objectification of women

Objectification of women’s bodies is another aspect of gender discrimination and bullying. Bullying against women in the workplace involves repeated and unreasonable verbal, physical, or sexual mistreatment by a person or a group (Al-Surimi et al. Citation2020). Saudi law criminalises such behaviour in general (Sian et al. Citation2020); however, some of our participants reported male superiors in mixed-gender environments bullying female workers based on their physical appearance. Samah reported being the subject of bullying at the workplace:

A supervisor at my previous job wanted me to socialise in social activities unrelated to work … in the event, the men would tease me. It seemed more than professional networking. When I reported it to the director, he didn’t believe me and accused me of exaggeration, even though I showed him screenshots of the conversation. As a whistle-blower, I was fired.

Conclusion

This paper utilised interviews with Saudi women to investigate the dynamic interplay of education, work, and empowerment concerning local contextual realities and various forms of socio-cultural influences in KSA.

The Saudi government has repeatedly announced its commitment to end women’s marginalisation and emphasise empowerment through education and employment. However, these policies rarely account for the local realities faced and experienced by Saudi women. Our findings indicated that statistical figures showing changes in women’s involvement in the workforce mask deeper hindrances to their agency and inequalities. By examining past studies relating to the Nitagat policy, it seems that even though more recent policy development (such as Vision 2030) has attempted to address the shortcomings of the older policies, additional efforts are necessary. These efforts to bridge the gender gap through further policy modification seem to have failed to make legitimate headway in eliminating gender inequality but have reproduced disempowerment. Furthermore, the perspective from which legislation protecting women against gender discrimination and objectification has been developed has created further challenges and, in some cases, unlawful conditions in the workplace.

This study found a dually opposing influence of family in the Saudi context, which may act to enable or hinder a woman’s agency and empowerment. Social structure, therefore, may prove to be an implicit tendency towards female disempowerment.

Our findings challenge the application of commonly accepted measures of women’s empowerment, suggesting that empowerment does not simply entail education and employment. Factors such as incentives, career paths, viewpoints related to gender in the workplace, individual perceptions of self-value, interpersonal communication skills, traditional versus modern understanding of empowerment, and societal factors tend to influence the extent and nature of women’s participation in the labour market.

Empowerment has the potential to be context-specific, and people must understand it as such by including society, structure, and local context simultaneously. We argue that the government’s provision of empowerment through education and employment should recognise the more concealed and local issues affecting women. Society and government should be viewed as enablers rather than suppliers of empowerment.

Education should provide women with critical thinking and skills that enable them to engage in what constitutes genuine empowerment based on their local context. Women must recognise, negotiate and navigate the contextually relevant empowerment they need to advance. It is imperative to recognise that some forms of so-called empowerment could lead to the unintentional disempowerment of Saudi women. Thus, we call for further research to examine education and employment from the perspective of a diverse range of geographical and socio-cultural contexts in KSA, which can be used to inform future policy development.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Saudi Ministry of Education and the KAIMRC for funding and governing this project. We also thank the research team, i.e. Dr Othman Albarnawi, Dr Asaad Jawhar, Dr Mohmmad E. Ahmed, Dr Raynor S. Roberts, Dr Meredith Armstrong and Miss Kholoud Almehdar.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sajjadllah Alhawsawi

Dr Sajjadllah Alhawsawi is an assistant professor of English as a Foreign Language and an associate dean at the College of Science and Health Professions, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences. Dr Alhawsawi holds an MA in TESOL from the University of Exeter, UK, an MSc in research methods from the University of Sussex, UK and a PhD in education from the Centre of International Education and Development, School of Education and Social work, University of Sussex, UK. Dr Alhawsawi's research interest includes programme evaluation, teacher education, higher education, instructional design, sociology of education and pedagogical use of ICT university education.

Sabria Salama Jawhar

Dr Sabria Salama Jawhar is an accomplished assistant professor of applied and educational linguistics at KSAU–HS. She received her education from Newcastle University, UK, and has since dedicated her career to exploring the various aspects of classroom discourse, assessment, and the use of technology in higher education. Dr Jawhar's research interests are diverse, but she is particularly passionate about assessment, educational technology, AI and talk–in–interaction, and corpus linguistics, focusing on spoken corpora. Her work has been widely recognized in academic circles for its innovative approach and valuable contributions to the field of linguistics.

References

- Abdulla, F. 2005. Emirati Women: Conceptions of education and employment. Tucson: PhD thesis, University of Arizona.

- Abouammoh, A. M. 2018. “The Regeneration Aspects for Higher Education Research in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.” In Researching Higher Education in Asia, edited by J. Jung, H. Horta, and A. Yonezawa, 327–352. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-4989-7_19.

- Al-Ahmadi, T. 2003. “Practical Journalistic Training in Media Departments in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Field Study.” Journal of the Faculty of Arts Research 14 (53): 135–172.

- Al-Bakr, F., E. R. Bruce, P. M. Davidson, E. Schlaffer, and U. Kropiunigg. 2017. “Empowered but Not Equal: Challenging the Traditional Gender Roles as Seen by University Students in Saudi Arabia.” FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education 4 (1): 52–66.

- Al-Surimi, K., M. Al Omar, K. Alahmary, and M. Salam. 2020. “Prevalence of Workplace Bullying and its Associated Factors at a Multi-Regional Saudi Arabian Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study.” Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 13: 1905–1914. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S265127.

- Alfarran, A., J. Pyke, and P. Stanton. 2018. “Institutional Barriers to Women’s Employment in Saudi Arabia.” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 37 (7): 713–727. doi:10.1108/EDI-08-2017-0159.

- Alharbi, R. 2015. Guardianship Law in Saudi Arabia and its Effects on Women’s Rights. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.34304.12801.

- Alhawsawi, S. 2014. “Investigating Student Experiences of Learning English as a Foreign Language in a Preparatory Programme in a Saudi University.” PhD diss., The University of Sussex. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/48752/.

- Alshanbri, N., M. Khalfan, and T. Maqsood. 2015. “Localization Barriers and the Case of Nitaqat Program in Saudi Arabia” Journal of Economics, Business and Management 3 (9): 898–903. doi:10.7763/JOEBM.2015.V3.305.

- Alsqoor, M. 2018. “How has King Abdullah Scholarship Program Enhanced the Leadership Skills of Saudi Female Beneficiaries?” PhD diss., The University of St. Thomas. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/113/.

- Bao, D., P. L. Ha, and O. Barnawi. 2019. “Mobilities, Immobilities and Inequalities: Interrogating Travelling Ideas in English Language Education and English Medium Instruction in World Contexts.” Transitions: Journal of Transient Migration 3 (2): 101–107. doi:10.1386/tjtm_00001_2.

- Barnawi, O. Z., and S. Al-Hawsawi. 2017. “English Education Policy in Saudi Arabia: English Language Education Policy in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Current Trends, Issues and Challenges.” In English Language Education Policy in the Middle East and North Africa, edited by R. Kirkpatrick, 199–222. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46778-8_12.

- Bhaskar, R. 2008. A Realist Theory of Science. Oxon: Routledge.

- Carvalho-Pinto, V. 2012. Nation-Building, State and the Gender framing of Women’s Rights in the United Arab Emirates (1971–2009). Reading: Ithaca Press.

- Creswell, J. W., and C. N. Poth. 2016. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. New York: Sage.

- Doumato, E. A. 2000. Getting God’s Ear: Women, Islam, and Healing in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Engin, M., and K. McKeown. 2017. “Motivation of Emirati Males and Females to Study at Higher Education in the United Arab Emirates.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 41 (5): 678–691. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2016.1159293.

- Findlow, S. 2012. “Higher Education and Feminism in the Arab Gulf.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 34 (1): 112–131. doi:10.1080/01425692.2012.699274.

- Global Gender Gap Report. 2021. https://www.weforum.org/reports/ab6795a1-960c-42b2-b3d5-587eccda6023.

- Golkowska, K. 2017. “Qatari Women Navigating Gendered Space.” Social Sciences 6 (4): 1–10. doi:10.3390/socsci6040123.

- Hasso, F. 2009. “Empowering Governmentalities Rather Than Women: The Arab Human Development Report 2005 and Western Development Logistics”. International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 41 (2009): 63–82. doi:10.1017/S0020743808090120.

- Haynes, K. 2012. “Reflexivity in Qualitative Research.” In Qualitative Organisational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges, edited by G. Symon and C. Cassell, 72–89. Chicago: Sage.

- James, A., and N. Shammas. 2018. “Teacher Care and Motivation: A New Narrative for Teachers in The Arab Gulf.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 26 (4): 491–510. doi:10.1080/14681366.2017.1422275.

- Jamjoom, L. 2020. “The Narratives of Saudi Women Leaders in the Workplace: A Postcolonial Feminist Study.” PhD diss., University of Saint Mary’s.

- Jawhar, S., S. Alhawsawi, A. S. Jawhar, M. E. Ahmed, and K. Almehdar. 2022. “Conceptualising Saudi Women’s participation in the Knowledge Economy: The Role of Education.” Heliyon 8 (8): e10256. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10256.

- Kabeer, N. 2020. “Women’s Empowerment and Economic Development: A Feminist Critique of Storytelling Practices in “Randomista”.” Economics. Feminist Economics 26 (2): 1–26. doi:10.1080/13545701.2020.1743338.

- Krause, W. 2009. “Gender and participation in the Arab Gulf.” In The transformation of the Gulf: politics, economics and the global order, edited by D. Heled and K. Ulrichsen, 105–124. London: Routledge.

- Krause, W. 2011. “Women in the Arab Gulf: Redefining Participation and Socio-Political Consequences.” German Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture of Middle East 5 (52): 12–17.

- Lacroix, S. 2011. Awakening Islam. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Marten, S. 2018. “Female Labour Force Participation in Saudi Arabia: Saudi Women and Their Role in the Labour Market Under Vision 2030.” PhD diss., The University of Lund.

- MoE. 2020. “Statistics 2010–2018.” https://www.moe.gov.sa/en/education/highereducation/Pages/default.aspx.

- Mohanty, C. T. 2006. “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses.” Feminist Review 30 (1): 61–88. doi:10.1057/fr.1988.42.

- Monkman, K. 2011. “Framing Gender, Education and Empowerment.” Research in Comparative and International Education 6 (1): 1–13. doi:10.2304/rcie.2011.6.1.1.

- Nunley, J. M., A. Pugh, N. Romero, and R. A. Seals. 2017. “The Effects of Unemployment and Underemployment on Employment Opportunities: Results from a Correspondence Audit of the Labor Market for College Graduates.” ILR Review 70 (3): 642–669. doi:10.1177/0019793916654686

- Prager, L. 2020. “Emirati Women Leaders in the Cultural Sector from “State Feminism” to Empowerment?” Journal of Women of the Middle East and the Islamic World 18 (2020): 51–74. doi:10.1163/15692086-12341370.

- Saudi Ministry of Labor and Social Development. 2019. “Controls Concerning the Protection against Behavioural Aggression in the Work Environment”. https://hrsd.gov.sa/sites/default/files/20912.pdf.

- Saudi Vision 2030. 2016. https://vision2030.gov.sa/download/file/fid/417.

- Seeberg, V. 2011. “Schooling, Jobbing, Marrying: What’s a Girl to Do to Make Life Better? Empowerment Capabilities of Girls at the Margins of Globalisation in China.” Research in Comparative and International Education 6 (1): 43–61. doi:10.2304/rcie.2011.6.1.43.

- Sian, S., D. Agrizzi, T. Wright, and A. Alsalloom. 2020. “Negotiating Constraints in International Audit Firms in Saudi Arabia: Exploring the Interaction of Gender, Politics and Religion.” Accounting, Organisations and Society 84: 101–103. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2020.101103.

- Syed, J., F. Ali, and S. Hennekam. 2018. “Gender Equality in Employment in Saudi Arabia: A Relational Perspective.” Career Development International 23 (2): 163–177. doi:10.1108/CDI-07-2017-0126.

- Vision 2021. 2021. Accessed 12 March 2020. Available from: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/strategies-plans-andvisions/strategies-plans-and-visions-untill-2021/vision-2021#:∼:text=Vision%202021%20is%20a%20long,its%20formation%20as%20a%20federation.

- Williams, A., J. Wallis, and P. Williams. 2013. “Emirati Women and Public Sector Employment: The Implicit Patriarchal Bargain.” International Journal of Public Administration 36 (2): 137–149. doi:10.1080/01900692.2012.721438.