ABSTRACT

Most secondary (high) schools in a broad range of jurisdictions internationally engage in various forms of high stakes, standardized assessment and related qualifications. In this paper, we interrogate how educational achievement regimes – especially via the reporting of curriculum and assessment ‘data’ – continue to mobilize particular gender norms. Drawing on Derrida’s notion of haunting we explore how such regimes impose and reinscribe stable and binary gendered patterning and create what Barad has named ‘entangled relationalities of inheritance’ [https://doi.org/10.3366/drt.2010.0206,] despite young people (and many schools) moving towards greater recognition of non-binary genders. Drawing on assessment data from Aotearoa New Zealand, we look at both generalized reporting of educational achievement data along the lines of ‘male’ and ‘female’ and on reporting of a single (historically gendered) curriculum subject – health education. We argue that such systems are ‘haunted’ by stable gender categorizations and hierarchies and we ask what this means for the reporting of educational assessment data and the erasure of identities that don’t align with the binary.

Introduction

Young people in many schools globally are actively engaged in formal state-sanctioned – and often compulsory – assessment regimes that engage with, report on and bestow high-stakes qualifications (Au Citation2022; Lingard, Martino, and Rezai-Rashti Citation2013). While these assessment regimes serve many purposes (Gipps Citation2011) they both gate-keep and enable access to higher education and employment, and they are used nationally and globally to frame policy and practice (Lingard, Martino, and Rezai-Rashti Citation2013; Mundy et al. Citation2016). In this paper, we interrogate how educational achievement regimes – especially via the reporting of assessment ‘data’ – continue to actively mobilize and reinscribe particular gender norms. Drawing on the work of Derrida (Citation1994) and other scholars who have used his work, we have taken the theoretical point of ‘haunting’ as a way of explaining how some assessment regimes stabilize and formalize binary genders, despite the increasing recognition of non-binary genders and the related questioning of binaries (McBride and Neary Citation2021). This is particularly powerful because senior high school assessments directly represent educational success and are reproductive of other forms of social and educational capital.

To illustrate, we draw on the example of high-stakes national assessment frameworks in Aotearoa New Zealand (the National Certificate of Educational Achievement, NCEA). We also attend to how gender binaries are entangled with curriculum and subject hierarchies, and ask how the particular subject of health education is positioned within this. We chose this regime – the NCEA – because it is a state-sanctioned, national high-stakes system that impacts almost all young people in Aotearoa New Zealand. We focus on health education because it has curious gendered ‘patterns’ of enrolment and engagement that show up in the reported statistical data and which echo school subject hierarchies that place STEM subjects as more objective, more difficult and more suited to boys (Jaremus et al. Citation2020; Wolfe Citation2021; Citation2019) and social science and humanities subjects as softer, more contingent and more feminine. Gender and school subjects are more complex than this, of course, but health education has long suffered, not only from such knowledge hierarchies but from a highly marginal position as a subject at all. Indeed, Aotearoa New Zealand is highly unusual internationally in including health education as a qualifications-level senior high school subject separate from physical education. In curriculum documents in many places (e.g. New Zealand, China, Australia, The UK, Canada) health tends to be linked with physical education, which in knowledge hierarchies is very established as ‘a body subject’ and has an entrenched status as non-academic (Evans, Davies, and Wright Citation2004; Kirk Citation2009).

The reporting of any educational achievement data and statistics can work agentically, within a respective assessment regime, to inscribe and harden gender binaries, and to impose gender categorizations on young people in schools. These can also reinforce disciplinary hierarchies in particular subjects because the achievement of ‘girls’ and ‘boys’ (or male and female) is reported in patterns showing high or low achievement or uptake by either group. The implications are important for understanding both how official assessment regimes impose and reproduce gendered notions of schooling success, and also how certain types of knowledge – in this case, knowledge about health and wellbeing – are reproductive of both gender binaries and knowledge hierarchies via supposedly objective ‘data’. We thus attempt here to explore the meeting point of gendered hauntologies of schooling, assessment regimes, and subject knowledge hierarchies.

We begin the paper by outlining the theoretical concept of haunting and how it applies to notions of educational and assessment ‘data’. We argue that all data are haunted (that this paper is haunted) and such hauntings create possibilities for how gender is seen, reproduced and reported in education. We then explain the production of the data we call up in this article and examine the implications of how such data is reported in ghostly ways. We end by reflecting on what this reporting does, especially when the data carry meaning both for young people and for policy.

Framework for analysis: haunting

Reporting of assessment data is often approached simplistically as objective and factual information about schooling achievement. However, the production of this data is more complex. We explore this here with Derrida’s (Citation1994) notion of hauntology and ask how assessment regimes are haunted by particular ghosts and what the impact of such ghosts might be for how we understand achievement and gender in schools. Derrida (Citation1994, 37) directly articulated his notion of hauntology through his readings of Marx and the spectres of communism, arguing that:

[a]t a time when a new world disorder is attempting to install its neo-capitalism and neoliberalism, no disavowal has managed to rid itself of all of Marx’s ghosts. Hegemony still organizes the repression and thus the confirmation of a haunting. Haunting belongs to the structure of every hegemony.

haunting describes how that which appears to not be there is often a seething presence, action on and often meddling with taken-for-granted realities, the ghost is just the sign, or the empirical evidence if you like, that tells you a haunting is taking place. The ghost is not simply dead or a missing person, but a social figure, and investigating it can lead to that dense site where history and subjectivity make social life.

Kenway (Citation2008) employed the concept of haunting to think about curriculum. Drawing on Dickens’ A Christmas Carol – and the ghosts of Christmas past, present, and future – as a metaphor, Kenway argued that hauntings also involve the ‘return of what is and has been ignored’ (12). Kenway (Citation2008) suggests that curriculum ‘ghosts’ provide a starting point for addressing ‘enduring, current, and emerging educational and social issues and problems’ (6). In the same way that the Ghosts of Christmas Past represent a time in which the cold-hearted and miserly Ebenezer Scrooge was kind and community focussed, Kenway (Citation2008) argued that the historical practice of democratic, school-based curricula could be ‘animated’ in response to the contemporary trend of decentralized and individualized curricula. For Kenway, lingering ghosts are learning devices that illuminate contemporary blind spots and thus disrupt the compliance-oriented foundation of current national curricula. However, such blind spots do not exist in a vacuum, as education is situated within (and therefore reflects) wider societal forces and values (Kenway Citation2008). Thus, considerations of curriculum ghosts, particularly given their timeless quality, are pertinent in the context of the contemporary, neoliberal fascination with ‘future proofing’. In this way, issues which are continuously ignored and/ or are addressed in isolation, will continue to reassert themselves as ghosts of curriculum present and future.

Francis and Paechter (Citation2015) argue that discussions around gender, both in terms of identity and expression, often ‘flow directly from the sexed body’ (778). In this sense, ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ are essentialized features of men/boys and women/girls, even in instances where gender is viewed as performative. For example, in Connell and Messerschmidt’s (Citation2005) work on masculinities (and in subsequent applications of this theorizing by other scholars) dominant, or hegemonic masculinities are constructed in relation to ‘subordinate’ masculinities, rather than femininity, regardless of how ‘feminine’ these performances of ‘subordinate’ masculinities are (Francis and Paechter Citation2015). Thus, behaviours enacted by men are always ‘masculine’, not because of the characteristics of the practices, but simply because they are performed by men (Youdell Citation2005).

Contemporary gender conceptualizations continue to be haunted by the gender binary and related collapsing of gender, sex, sexuality (Youdell Citation2005). The haunted nature of gender is further drawn out when examining trans and non-binary identities and bodies. Mina Hunt (Citation2021) argues that, ‘[t]he trans subject is haunted but also haunts’ (97). Trans identities and bodies are haunted by the gender binary via the expectation for them to appear as cis-normative, but also actively haunt the gender binary in the sense that their presence at all challenges and erodes the ‘previously imagined solidity of boundaries’ (Hunt Citation2021, 100). Further to these experiences of haunting are instances of social and institutional misgendering – which demonstrate the ways that trans people are haunted by gender as designated at birth – and the associated, often conflicting, paper trail of haunted identity documents (Hunt Citation2021). Although a specific analysis of trans and non-binary students is not the central focus of this paper, the acknowledgement of the ways that trans identities and bodies haunt and are haunted by gender is an important nuance to note in our broader interrogation of gender, education, and data.

For our purposes here, we use these ideas to investigate how assessment regimes in schools are haunted along gendered lines and in relation to past-present-future ghosts. We argue that the ways data are produced, reported and reproduced, serve binary gendered patterning and ghostly subject hierarchies. Supposedly stable patterns of educational achievement haunt the data and our intention is to interrogate and question how data reporting reinscribes gendered notions of curriculum and achievement, and to explore what such hauntings are indicative of. Gordon’s (Citation1997) argument above highlights the importance of time in this analysis. Assessment data – as we will show – are presented with an assumption of truth and objectivity but actually represent particular articulations of essentialized gender (as ascribed at birth) and historical narratives of curriculum engagement and curriculum hierarchies. These occur simultaneously as data are haunted and reproductive, rather than the linear, sequential and/or parallel relationship that is often assumed.

Haunted artefacts: the problem of engaging with data

Before we present the data at the centre of this paper, we reflect first on the problems with doing data work, with invoking ghostly data. We chose to engage with statistical data produced within the official assessment regime of the place we live. We did not, however, do this without a lot of consideration about how such data – and our re-use of it – reinforces particular regimes of truth. Denzin (Citation2019) argues that considering the production, reproduction, and purposing of educational data is fraught and the very term is contested in qualitative research. Denzin (Citation2019, 721) asks,

Big data, soft data, hard data, data stored in clouds, weak data, data as evidence, evidence as data … . What do we mean by data and for whom in neoliberal times? We are at an uneasy, troubled crossroads; the demands of neoliberalism, audit cultures, pragmatism, and posthumanism intersect in a troubled space.

Denzin (Citation2019) pointed out that the notion of data, the word data, the use of data died off (or was killed off) because, ‘[p]oststructuralism took away positivism’s claim to a God’s eye view of the world – that view which said objective observers could turn the world and its happenings into things that could be turned into data’ (722). Data were killed, he argued, by feminist poststructuralism and the need to decolonise. He argued that the death went unnoticed and so ‘[t]he dreaded word keeps resurfacing, still hanging around, even in deconstructionist discourse’ (722). For Denzin (Citation2019), interrogating the processes of data production and reporting is important and he asserts that ‘[t]here is a need to unsettle traditional concepts of what counts as research, as evidence, as legitimate inquiry’ (723). Data too often evoke and reinforce moves towards ever greater technological rationalities. We are with Denzin in resisting practices of data but acknowledge that data are (re)used, (re)created, and (re)produced in educational contexts in powerful and power-laden ways. Assessment data are used as a specific regime of classification that carries meaning and holds status. Achievement data ‘does something’ in education through structuring access, framing educational success, and reproducing subjectivities. It is a form of capital (Bourdieu Citation1986) and a governing technology (Foucault Citation1991). It is haunted and it haunts. We are also compelled to interrogate and challenge the data but doing so re-haunts, calls up the very ghosts we wish to exorcise.

Making and reporting ‘data’

For this study, we invoke two kinds of data both collected, held and used by a government agency (the New Zealand Qualifications Authority, NZQA) charged with the responsibility for bestowing official secondary school qualifications. We accessed the first kind of data by going to the NZQA website and using their publicly available tables. The second form of data we use here are achievement statistics held by the authority but which must be requested. In requesting these ‘data’, we engaged in our own haunted practices: bringing the ‘data’ to light and actively engaging in reinscribing gendered categorizations through our very request. These data exist and do not exist simultaneously. The Qualifications Authority (NZQA) hold and maintain achievement databases and uses these to gate-keep and ascertain and award credentials, but they only report certain categorizations publicly. We requested the statistical data for NCEA in health education from NZQA, and the achievement data as identified by gender. We wanted to interrogate the data and ask questions about which students – or what categories – appear or are represented nationally in secondary schools. We received the requested gender data held by the Authority in an Excel format; this aligned with the authority’s standard coding for gender as ‘male’ and ‘female’. A note was added that a third category (referred to as gender ‘Not Stated’) was ‘not included in this output due [to] the small number of students in this category’. This signifies the first haunting, the missing data of students whose gender is not stated or is missing; this category is both unexplained and spectral. It haunts the binary reporting as an absent presence.

The NCEA assessment system: reporting data by gender

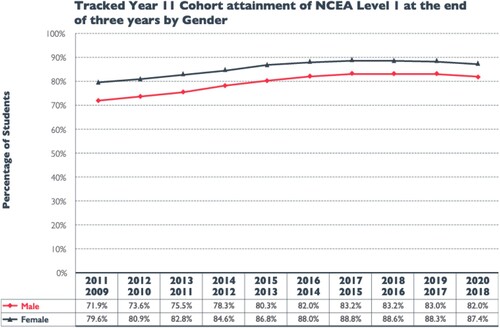

The NCEA system produces reports labelled as ‘by gender’ but uses the terms ‘male’ and ‘female’ as gender categories thus collapsing gender assigned at birth and forcing students-as-achievement-data into graphs haunted by gender binaries and achievement hierarchies. How these are then ‘reported’ are evident in (NZQA Citation2020, 11). This figure is publicly available on a government-sponsored website that tracks and reports achievement data over time.

reports on student achievement of Level 1 of the NCEA (the lowest possible qualification) by the end of schooling. It shows patterns over time of male and female achievement. The imposed category of ‘female’ is used here to illustrate and manufacture stable patterns of educational success over an 11-year period and across cohorts of students. In so doing, it obscures other subject positions and solidifies achievement patterns as evident and embedded in the system, as a form of truth that ‘females’ achieve more than ‘males’ at school. This table claims to represent all students in school between the years of 2009 and 2020. It has tracked which students attained Level 1 (the lowest NCEA qualification) by the time they had completed the final three years of school. The note on this graph that ‘students with unknown gender have been omitted from this table’ shows that not all student-related data are represented here. What is not named is that students without reported results are also erased, as are young people not in school.

Dixon-Roman (Citation2017) argues that ‘data are heir of the fictively constructed genres of being human, while autopoietically instituting them’ (55). Human-subject data, such as that shown in , exist upon, within, and alongside of, ontological narratives and myths of people (Dixon-Roman Citation2017). Broadly we can think about this as the sociogenic categories and classifications such as gender, race, ability, and sexuality that are imposed within data regimes on human subjects, rather than reflecting and emanating from them. It is therefore important to consider the historically-situated contexts in which these codes were produced, as such categorizations continue to reflect the systems of values and beliefs which produced them. Drawing on race, Dixon-Roman (Citation2017) notes, that the histor(icit)y of educational data is rooted in the initial social constructions of categories and assessment mechanisms, which sought to establish cultural and biological differences as a justification for white supremacy. These data do the same kind of work in terms of creating hierarchies of achievement over time. However, reporting by gender has its roots in a will to make visible gendered differences in schooling success. So, reporting gender – like that in – is perhaps intended to communicate a gendered pattern of achievement, one that shows that those ascribed ‘female’ as a population consistently achieve more than those who are ascribed ‘male’. Bridges (Citation2021) notes that, ‘[d]ata must first be imagined before being called into existence’ (3). This NCEA data imagines the categories of female and male and then invokes this ghostly binary to argue that females do better in the system than males. Such human-subject data, relying as they do upon invisible and naturalized classifications, are then possessed by historically-rooted sociogenic codes and inherit the values and beliefs associated with them. Binary gender categories here thus reproduce ghostly notions of male/female and it is worth asking whether these align in any way with how young people identify themselves or how gender is experienced in schooling and assessment. Fisher (Citation2012, 19, emphases in original) notes that hauntings take the form of both what is no longer and what is not yet:

The first refers to that which is (in actuality is) no longer, but which is still effective as a virtuality (the traumatic ‘‘compulsion to repeat,’’ a structure that repeats, a fatal pattern). The second refers to that which (in actuality) has not yet happened, but which is already effective in the virtual (an attractor, an anticipation shaping current behavior).

Reporting of gender data as ‘male’ and ‘female’ achievement in school, as shown in , exemplifies what Connell (Citation2012, 1675) calls ‘categorical thinking’ which ‘takes a dichotomous classification of bodies as a complete definition of gender’. Connell (Citation2012, 1676) points out that such thinking has been central to hard fought reforms in education based on understanding and exposing gender stereotypes and ‘to provide services to women and girls as an under resourced category’. However, such categorizations also essentialize gender as reflective only of biology. As a result, the data in serve to harden gender binaries and erase reporting of data that falls outside of this binary, it also reinscribes gender (assigned at birth) as the only valid and inherent ‘difference’ to be examined, monitored and reported. This is particularly important to consider in light of how such data are used to limit groups of students and then make inferences about achievement ‘gaps’ and patterns, that are only meaningful through comparison and difference to other categories (Gutiérrez and Dixon-Román Citation2011).

The NCEA assessment system: health education and gender

As with the overall NCEA achievement data, data pertaining to the subject health education, reflects a similarly haunted position. Health education in New Zealand is a subject available to study in the NCEA system and, therefore, is a credentialed curriculum subject in the national qualification. This is unusual internationally. In most nation states, health holds a very different place in schools as a site of intervention and health promotion (Gard and Pluim Citation2014), rather than a curriculum subject of study. Health education data here, however, are haunted not only by binary gender reporting but the subject itself has a history of being ascribed ‘female’ in the reporting, and entangled with epistemological hierarchies that classify school subjects (Paechter Citation1998; Citation2000).

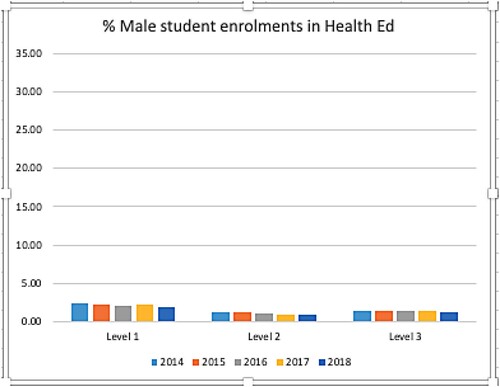

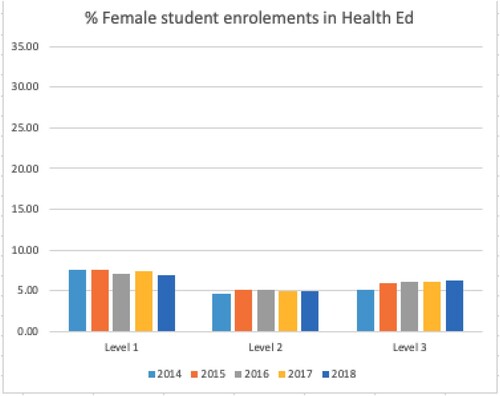

We requested health education achievement data from the Qualifications Authority. Their data insisted that three to four times more results were apparent for female-identified students than for male-identified students over a 5-year period (as shown in and 3).

reports the data that NZQA holds on ‘male’ students enrolled in three or more NCEA achievement standardsFootnote1 in health education. We used this as a measure of studying health education in senior high school. shows the same data for ‘female’ students. These data insist that about 7–8% of all students in school who are designated ‘female’ are reported as studying health education as a subject at Level 1 (this is typically Year 11, students who are usually 15–16 years of age). In the penultimate year of high school (Year 12; ages 16-17) this drops closer to 5% and then goes up slightly for the Year 13 cohort (ages 17–18 years). Level 3 health education is a recognized subject for the University Entrance qualification and provides access to higher education and careers. By contrast, only 1–2% of ‘male’ students in the country choose to take health education as a subject at Level 1. This trend is stable for Years 12 and 13 with the data showing between 1–1.45%.

These manufactured graphs are spectral evidence of an entanglement that haunts the subject of health education, a school subject that occupies a curious position in relation to gender and knowledge hierarchies. As a subject connected with physical education in many national contexts (including in Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia and the UK), health education is aligned with low subject status, concerned with the body in a Cartesian hierarchy but also assumed to be non-academic and feminized as a soft subject (Leahy et al. Citation2015; Leahy and McCuaig Citation2014; Paechter Citation2000). It is conflated in schools with health promotion and interventions (Gard and Pluim Citation2014) and holds marginal status when labelled as ‘life skills’ or seen as a subject to teach students about risky behaviours and to promote prohibition (of drugs, alcohol, sex, etc) (Leahy Citation2014; Leahy et al. Citation2015). It is not – oddly – usually associated with health science, medicine, or psychology in the compulsory school sector, even though in some countries (such as in Aotearoa New Zealand and Australia) health education curriculum is directly informed by such disciplinary knowledge. In this sense, health education is temporally entangled with gender and, relatedly, status. It is haunted by Cartesian dualisms and as a result is in/validated as a worthy curriculum subject (Paechter Citation1998; Citation2000). This perhaps explains why health education only has official subject status in senior high school qualifications in a handful of countries.

Schools have particular kinds of investment in gender norms and practices. While these are complex, McBride and Neary (Citation2021) argue that ‘[i]n many respects, schools hinge on the presumption of a stable cisgender norm – the normalised assumption that everyone identifies with the gender assigned to them at birth; and, that sexed anatomy/gender identity congruence is immutable and fixed at birth’ (1090). This presumption is mirrored and reinforced in many technologies, including via assessment regimes. Curriculum subject hierarchies articulate this in the sense that STEM subjects have a strange confluence with masculine notions of success and identity. Hussénius (Citation2020) notes that ‘[a]n historical imbalance of power, characterized by masculine gender coding, still exists and is expressed at both structural and symbolic levels in STEM education’ (573–574). This same imbalance is apparent in how gender is read in disciplines in the social sciences and humanities.

Making sense of our ghostly educational data

There are several hauntings evident in these data. First is the inscription of gender binaries and the erasure of students who identify as gender diverse or in any way outside the terms male/female. McBride and Neary (Citation2021) argue that ‘institutionalised educational cisnormativity stigmatises young people who identify as trans or gender diverse and perpetuates prejudice against youth who transgress normative boundaries of gender expression’ (1090). In this section, we explore trans erasure and how this connects to existing research and policy.

Ghostly trans erasure

International research shows a growing acknowledgement of, and interest in, gender diversity within educational environments. Young people’s understandings of gender are increasingly nuanced (Bower-Brown, Zadeh, and Jadva Citation2021; Bragg et al. Citation2018; Paechter, Toft, and Carlile Citation2021), and transgender and gender diversity have become key issues of interest in educational policy at a global level (Jones et al. Citation2016). Yet, Hunt’s (Citation2021) assertion of the haunted and haunting trans subject explored above is ever present. Indeed, the use of essentialized language in the reporting of NCEA achievement and enrolment data highlights how notions of gender continue to ‘flow from the sexed body’ and are predicated upon historically-rooted sociogenic codes. Further, students who fall into the ‘not stated’ category are excluded from representation, and more broadly there is no scope in this data for trans, non-binary, and gender-questioning students. The latter two are invisible and trans students are likely to be mis-gendered in the representation of their achievement data. It is worth asking why assessment data are reported by gender at all and, if they are, why so few attempts are made to ensure any alignment with how students identify. If we take the view that data is an artefact of wider regimes of truth, then we can see how such data aid in the hardcoding of the gender binary into our educational systems and the continued exclusion and erasure of trans and non-binary identities and bodies. It suggests gender achievement matters but this mattering is not made clear. This is especially ironic in relation to NCEA health education in Aotearoa New Zealand, which has specific assessments that require students to ‘Analyse issues related to sexuality and gender to develop strategies for addressing the issues’ (health education achievement standard, level 2). This is ironic because the curriculum and assessment conceptualize gender beyond binaries and require students to critique the limitations of binaries (Ministry of Education Citation2020a; Citation2020b). But the reporting of their achievement in these assessments reinstates the very binary they are asked to critique.

Policy accommodations and protections that speak to gender diversity are often less detailed and publicized than those that address sexual diversity (Bower-Brown, Zadeh, and Jadva Citation2021; Jones et al. Citation2016). In Jones et al.’s (Citation2016) study on the school experiences of transgender and gender-diverse students in Australia, half of their participants identified outside of the gender binary and one-quarter suggested that they avoided school because they could not conform to ‘the gender stereotypes dominant within these contexts’ (163). Similarly, Bragg et al. (Citation2018), writing about the UK, suggested that, while there was evidence of supportive and gender-inclusive environments in their study, ‘schools were generally structured and operated in ways that reinforced the notion of gender identity and expression as binary’ (430). Indeed, Bower-Brown, Zadeh, and Jadva (Citation2021) described the UK’s education system as ‘ill-equipped’ to support trans, non-binary, and gender-questioning students, owing to a lack of social and legal recognition of trans and non-binary subjectivities, particularly those which fall outside of the gender binary. Scholars have identified the lack of provisioning for gender-neutral toilets, changing facilities, uniforms, and sports as reoccurring hurdles in this area (Bragg et al. Citation2018; Jones et al. Citation2016). It is worth noting that while these issues impact trans and non-binary people alike, research suggests that progressive educational systems may be more supportive of students who are read as ‘binary-trans’ because schools can accommodate these students within the established gender binary, rather than developing gender-neutral or gender queer solutions (Bower-Brown, Zadeh, and Jadva Citation2021; Paechter, Toft, and Carlile Citation2021).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, trans and non-binary students encounter similar barriers. The Youth19 survey (a health and wellbeing survey of secondary school students) found that 1% of students surveyed identified as trans or non-binary and a further 0.6% were unsure of their gender (Fenaughty et al. Citation2021, 1). Of these students, 70% suggested that they felt part of their school, which was significantly lower than the 87.1% of cisgender students who felt the same (3). One explanation for this disparity is the differential availability of support. In Counting Ourselves, an earlier community survey of trans and non-binary people living in New Zealand, 80% of secondary school students reported having access to a safe space to meet other trans and non-binary students, whereas only 45% reported having access to a gender-neutral uniform (Veale et al. Citation2019, 63). On the issue of bathrooms, less than half of secondary students surveyed in Counting Ourselves had access to a unisex toilet at their school (Veale et al. Citation2019, 62).

However, in Aotearoa New Zealand, gender and sexuality diversity is specifically addressed in national Ministry of Education policy, and schools are required to provide inclusive environments, rethink gendered toilets and uniforms, and respect students’ right to have their name and gender of choice on the school role (Ministry of Education Citation2020a; Citation2020b).Footnote2 While work is ongoing to create changed practices in schools, these are not well publicized nor resourced (New Zealand Human Rights Commission Citation2020, 52). For example, the Education Review Office (Citation2018) found that many school ‘leaders and trustees saw [gender-neutral bathrooms] as being prohibitively expensive or not possible with current property arrangements’ (10). Further, while some schools had updated their electronic student management systems to include diverse gender options, the software would not successfully update the national enrolment system with these new options selected, as binary gender options are still exclusively used at a national level (Education Review Office Citation2018, 27). Indeed, national enrolment data in Aotearoa New Zealand uses birth certificates to determine eligibility to study, meaning that trans and non-binary students must amend their birth certificates to have their identities accurately reflected in their enrolment information (Governance and Administration Committee Citation2021). Up until recent legislative reform (see: Governance and Administration Committee Citation2021), these changes had to be processed through the Family Court which required evidence of medical transitioning and did not include any provisions for non-binary sex markers such as ‘intersex’ or ‘X (unspecified)’.Footnote3

These examples demonstrate how powerful the ghosts of gender binaries are in New Zealand’s legislative system and consequently the educational system. While officials underscore that the use of birth certificates to determine eligibility to study in New Zealand does not prevent trans and non-binary students from using a different name and gender at school (Governance and Administration Committee Citation2021, 20), it does not address the more systemic problems related to how such data is then used to inform policies nor to make inferences about the student population. Thus, despite education policy signalling of gender inclusivity, schools in Aotearoa New Zealand continue to be haunted by the gender binary, which is then reinscribed upon students and hardened as achievement data that follows them and their cohorts in endless repetition.

Ghostly informants: enduring data temporalities

Data such as that reported on by the NCEA is part of a wider assemblage of both gender and education in the sense that it is used as a tool to inform decisions made about the population it is describing (thereby not just returning the data to those haunted designations but the populations themselves). In line with the argument made by Dixon-Roman (Citation2017), such hauntings highlight the limitations of our data, in the sense that it is self-referential, and also how that limitation in itself is part of the broader problem of reproducing gender categorization.

Data are also haunted by the past through the reproduction of accountabilities, these are particular expressions in educational assessment and achievement regimes because of claims for consistency, monitoring, and an expressed need to do comparisons across years. So, data regimes are stable as they report and compare past data against current data. Categories are resistant to change because change works against consistent comparison. Consider the way that Statistics New Zealand (the primary agency responsible for collecting and reporting national-level statistics, Stats NZ) redefined their statistical standard for gender to include ‘Another Gender’ in addition to the standardized ‘Male’ and ‘Female’ classifications (Stats NZ Citation2021, 12). While the inclusion of ‘another gender’ enables non-binary identities to be (re)presented in the data, this addition reflects an expansion to existing gender categories rather than a fundamental change of gender categorization itself. By this, we mean that the (re)presentation of non-binary data will likely be framed as a newly discovered gender category, rather than one which was carved out or siphoned off pre-existing categories.

This relationship between data categorization, change, and expansion, reflects one of the ways in which data science is ‘caught up’ with ‘tales of … continuous accretion’ (Barad Citation2010, 244). Barad’s use of the word ‘tales’ draws attention to the fictitious construction of science as a ‘bedrock of solid and certain knowledge’ (244) wherein knowledge is linearly refined through expansion. Yet, data is demonstrably temporal. Simply asking where and how non-binary data was categorized prior to the expansion of gender categories, reveals data to be simultaneously inclusive and exclusive; known and unknown. Thus, the narrative which (re)presents data linearly as exclusive and then inclusive; unknown and then known, is a fiction. This temporal nature highlights Barad’s (Citation2010, 264) assertion of the ‘noncontemporaneity of the present’ in the sense that present data is entangled with past data in complex ways. As Barad (Citation2010) argued, ‘[t]here is no fixed dividing line between … “past” and “present” and “future”’ (265). The haunting of data therefore describes the ‘entangled relationalities of inheritance’ (264) between past and current data practices and regimes.

Conclusion

Assessment regimes record, mobilize and report student achievement as data and – in so doing – reinscribe binary gendered patterning in ways that insist these are stable and normalized. Assessment regimes gate-keep educational success and access to higher education and other forms of social and educational capital. Students and schools cannot opt out, they cannot change the system and they cannot insist on different gender identities (or even names) as part of this system. Schools engage in actively reinscribing gender binaries in ways that are not only difficult to unpick, but impossible for students to dissociate from. The NCEA assessment regime is one example. A high-stakes assessment system – like many internationally – it gatekeeps access to higher education through a framework of educational capital and credentialling. NCEA data is generated through schools reporting student grades in individual achievement standards, which are both internally assessed (by schools) and through nationally-invigilated examinations. These are all recorded and reported along a male/female binary with no other categories reported in the regime. The imposition of such a framework, along with its compulsory and compulsive signification of status and success in the education system, hardens ‘male’ and ‘female’ irrevocably and ties these categories to gender assigned at birth. Such reinscribing is powerful in such a high-stakes state-sanctioned regime and is contra to the ways young people are themselves thinking about gender. It is an example of what Connell (Citation2012) calls ‘categorial thinking’ that imposes assumed gender oppositions. This phenomenon and its repetition has important implications. In the case of individual students, they have to endure another system that erases or ignores the ways they want to be known, and refuses to report categories that are lived but not validated in statistics. And this is not just another system but one which stays with them and determines access to other systems and forms of status (jobs, higher education) for many years. There are wider implications here too in the sense that global regimes of assessment data are policy-forming at a national and international level (Lingard, Martino, and Rezai-Rashti Citation2013) and thus manufacture gendered discourses of schooling achievement such as the failure of boys in high school ((e.g. Martino and Rezai-Rashti, Citation2017), the unwillingness of girls to choose STEM subjects (Wolfe Citation2021), or the feminization of subjects such as health education (Paechter Citation2000). These discourses are mobilized via assessment data that erases non-binary categorizations and forms policy only for the imagined singular categories of male and female.

It is worth asking why these data insist on such limited gender classifications and reporting at all. These serve to haunt education and insist on categories which do not reflect the range of genders ; this becomes a compulsive repetition, an insistence that gender binaries are inherent, stable, existent Such entangled relationalities resist the ‘not yet’ (Fisher Citation2012) in schools, the future potential education system where other gender articulations are already obvious but simultaneously denied. The assessment data reported in this paper then are haunted by gender categories that no longer align with those in wider society and certainly in policy in Aotearoa New Zealand. The NCEA system then is haunted by ghosts that refuse to rest.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aimee B. Simpson

Dr Aimee B Simpson is an Independent Scholar with expertise in sociology, critical education studies and professional development in higher education. Her research interests include fat studies, health, bodies, inequity and academic precarity.

Katie Fitzpatrick

Professor Katie Fitzpatrick is a member of Te Kura o Te Marautanga me te Ako/School of Curriculum and Pedagogy at Waipapa Taumata Rau/ University of Auckland. Her research and teaching are focused on health education, physical education, mental health education, sexuality education, policy, poetic research methods, and critical ethnography.

Mohamed Alansari

Dr Mohamed Alansari is a senior researcher at the New Zealand Council for Educational Research. His research spans educational and social psychology, with a specific focus on institutional and classroom practices that impact the social and academic trajectories of student learning. He employs a mixed-method approach in his research, with a stronger focus on quantitative research methodologies. Mohamed explores educational ‘puzzles of practice’ from a social-psychological perspective, and has both experience and expertise in undertaking research at primary, secondary, and tertiary settings.

Notes

1 Achievement standards are the assessment unit in the NCEA. These are individual topics which are assessed against the standard and reported as individual results for students. Each ‘standard’ is worth ‘credits’ toward a certificate.

2 At the time of publication, the policy we cite here is also under question. The New Zealand coalition government has promised to remove and replace the current relationships and sexuality education curriculum. This is based on concerns about the teaching of gender and how this is articulated in the curriculum policy (see: https://www.1news.co.nz/2024/04/18/changes-to-gender-sexuality-education-whats-in-the-guidelines/)

3 New Zealand birth certificates have 3 possible categories for sex :male, female and indeterminate. The latter is explained as “indeterminant means your doctor or midwife could not determine the sex of your baby”. In 2021, the law was changed to allow adults (and those 16–17 years with support from an adult), to change their birth certificate to either male (m), female (f) or gender diverse (x).

References

- Au, W. 2022. Unequal by Design: High-Stakes Testing and the Standardization of Inequality. New York: Routledge.

- Barad, K. 2010. “Quantum Entanglements and Hauntological Relations of Inheritance: Dis/Continuities, Spacetime Enfoldings, and Justice-to-Come.” Derrida Today 3 (2): 240–268. https://doi.org/10.3366/drt.2010.0206

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson, 241–260. Greenwood: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Bower-Brown, S., S. Zadeh, and V. Jadva. 2021. “Binary-trans, Non-Binary and Gender-Questioning Adolescents’ Experiences in UK Schools.” Journal of LGBT Youth 20 (1): 74–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2021.1873215.

- Bragg, S., E. Renold, J. Ringrose, and C. Jackson. 2018. “‘More Than Boy, Girl, Male, Female’: Exploring Young People’s Views on Gender Diversity Within and Beyond School Contexts.” Sex Education 18 (4): 420–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1439373.

- Bridges, L. E. 2021. “Digital Failure: Unbecoming the “Good” Data Subject Through Entropic, Fugitive, and Queer Data.” Big Data & Society 8 (1-17). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720977882

- Connell, R. 2012. “Gender, Health and Theory: Conceptualizing the Issue, in Local and World Perspective.” Social Science & Medicine 74 (11): 1675–1683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.006

- Connell, R. W., and J. W. Messerschmidt. 2005. “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.” Gender & Society 19 (6): 829–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639

- Denzin, N. K. 2019. “The Death of Data in Neoliberal Times.” Qualitative Inquiry 25 (8): 721–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419847501

- Derrida, J. 1994. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. New York: Routledge.

- Dixon-Roman, E. 2017. “Toward a Hauntology on Data: On the Sociopolitical Forces of Data Assemblages.” Research in Education 98 (1): 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034523717723387.

- Education Review Office. 2018. Promoting Wellbeing Through Sexuality Education. New Zealand: Author. http://www.ero.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Promoting-wellbeing-through-sexuality-education.pdf.

- Evans, J., B. Davies, and J. Wright. 2004. Body Knowledge and Control: Studies in the Sociology of Physical Education and Health. London: Routledge.

- Fenaughty, J., K. Sutcliffe, T. Fleming, A. Ker, M. Lucassen, L. M. Greaves, and T. Clark. 2021. A Youth19 Brief: Transgender and Diverse Gender Students. The Youth19 Research Group, The University of Auckland and Victoria University of Wellington. https://www.youth19.ac.nz/publications.

- Fisher, M. 2012. “What is Hauntology?” Film Quarterly 66 (1): 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2012.66.1.16

- Foucault, M. 1991. The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Francis, B., and C. Paechter. 2015. “The Problem of Gender Categorisation: Addressing Dilemmas Past and Present in Gender and Education Research.” Gender and Education 27 (7): 776–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2015.1092503.

- Gard, M., and C. Pluim. 2014. Schools and Public Health: Past, Present, Future. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Gipps, C. 2011. Beyond Testing (Classic Edition): Towards a Theory of Educational Assessment. London: Routledge.

- Gordon, A. 1997. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Governance and Administration Committee. 2021. Inquiry Into Supplementary Order Paper No. 59 on the Births, Deaths, Marriages, and Relationships Registration Bill. New Zealand: Author. https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/sc/reports/.

- Gutiérrez, R., and E. Dixon-Román. 2011. “Beyond Gap Gazing: How Can Thinking About Education Comprehensively Help Us (Re)Envision Mathematics Education?” In Mapping Equity and Quality in Mathematics Education, edited by B. Atweh, M. Graven, W. Secada, and P. Valero, 21–34. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9803-0_2

- Hickey, I. 2022. “Derrida, Hauntology, and the Spectre.” In Haunted Heaney: Spectres and the Poetry, 9–29. New York: Routledge.

- Hunt, M. 2021. “Tracing Transgender Ghosts.” Sociology and Technoscience 11 (1): 91–103. https://doi.org/10.24197/st.1.2021.91-103.

- Hussénius, A. 2020. “Trouble the Gap: Gendered Inequities in STEM Education.” Gender and Education 32 (5): 573–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2020.1775168.

- Jaremus, F., J. Gore, E. Prieto-Rodriguez, and L. Fray. 2020. “Girls are Still Being ‘Counted Out’: Teacher Expectations of High-Level Mathematics Students.” Educational Studies in Mathematics 105 (2): 219–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-020-09986-9

- Jones, T., E. Smith, R. Ward, J. Dixon, L. Hillier, and A. Mitchell. 2016. “School Experiences of Transgender and Gender Diverse Students in Australia.” Sex Education 16 (2): 156–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2015.1080678.

- Kenway, J. 2008. “The Ghosts of the School Curriculum: Past, Present and Future.” The Australian Educational Researcher 35 (2): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216880.

- Kirk, D. 2009. Physical Education Futures. London: Routledge.

- Leahy, D. 2014. “Assembling a Health [y] Subject: Risky and Shameful Pedagogies in Health Education.” Critical Public Health 24 (2): 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2013.871504

- Leahy, D., L. Burrows, L. McCuaig, J. Wright, and D. Penney. 2015. School Health Education in Changing Times: Curriculum, Pedagogies and Partnerships. New York: Routledge.

- Leahy, D., and L. McCuaig. 2014. “Disrupting the Field: Teacher Education in Health Education.” In Health Education: Critical Perspectives, edited by K. Fitzpatrick and R. Tinning, 238–250. New York: Routledge.

- Lingard, B., W. Martino, and G. Rezai-Rashti. 2013. “Testing Regimes, Accountabilities and Education Policy: Commensurate Global and National Developments.” Journal of Education Policy 28 (5): 539–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2013.820042

- Martino, W., and G. Rezai-Rashti. 2017. “‘Gap Talk’and the Global Rescaling of Educational Accountability in Canada.” In Testing Regimes, Accountabilities and Education Policy, 61–83. Routledge.

- McBride, R. S., and A. Neary. 2021. “Trans and Gender Diverse Youth Resisting Cisnormativity in School.” Gender and Education 33 (8): 1090–1107. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2021.1884201.

- Ministry of Education. 2020a. Relationships and Sexuality Education – A Guide for Teachers, Leaders, and Boards of Trustees: Years 1–8. New Zealand: Author.

- Ministry of Education. 2020b. Relationships and Sexuality Education – A Guide for Teachers, Leaders, and Boards of Trustees: Years 9-13. New Zealand: Author.

- Mundy, K., A. Green, B. Lingard, and A. Verger. 2016. The Handbook of Global Education Policy. England: Wiley Blackwell.

- New Zealand Human Rights Commission. 2020. Human Rights Issues Relating to Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression, and Sex Characteristics (SOGIESC) in Aotearoa New Zealand – A Report with Recommendations. New Zealand: Author. https://www.hrc.co.nz/resources/.

- NZQA (New Zealand Qualifications Authority NZQA). 2020. Annual Report: NCEA, University Entrance and New Zealand Scholarship Data and Statistics. New Zealand: Author.

- Paechter, C. 1998. Educating the Other: Gender, Power and Schooling. London: Routledge.

- Paechter, C. 2000. Changing School Subjects: Power, Gender and Curriculum. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press.

- Paechter, C., A. Toft, and A. Carlile. 2021. “Non-binary Young People and Schools: Pedagogical Insights from a Small-Scale Interview Study.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 29 (5): 695–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2021.1912160.

- Stats NZ. 2021. Data Standard for Gender, Sex, and Variations of Sex Characteristics. New Zealand: Author. https://www.stats.govt.nz/assets/Methods/Data-standards-for-sex-gender-and-variations-on-sex-characteristics.

- Veale, J., J. Byrne, K. Tan, S. Guy, A. Yee, T. Nopera, and R. Bentham. 2019. Counting Ourselves: The Health and Wellbeing of Trans and Non-Binary People in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand: Transgender Health Research Lab, University of Waikato. https://countingourselves.nz/.

- Wolfe, M. J. 2019. “Smart Girls Traversing Assemblages of Gender and Class in Australian Secondary Mathematics Classrooms.” Gender and Education 31 (2): 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2017.1302078

- Wolfe, M. 2021. Affect and the Making of the Schoolgirl: A New Materialist Perspective on Gender Inequity in Schools. New York: Routledge.

- Youdell, D. 2005. “Sex–Gender–Sexuality: How Sex, Gender and Sexuality Constellations Are Constituted in Secondary Schools.” Gender and Education 17 (3): 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250500145148.