ABSTRACT

The paper examines a ‘circulatory’ system of gender inequity in Australian universities where gender bias prevents women from accessing senior decision-making roles and stultifies their capacity to act as gender change agents. It has been mooted that equity quotas for senior roles can derail this circuit of male privilege in academia. Yet a plastic reading of the shape of gender equity policy and practice in Australian universities over the last 40 years reveals an increasing acceptance of individualism, which positions women’s liberation as being achievable through self-responsibilisation. If these discourses remain unchallenged, gender quotas for senior roles alone will likely only benefit those entrepreneurial women admitted to senior positions, rendering the causes of gender inequity hidden and exonerated. Using a novel methodology that combines a ‘plastic’ with a complex systems lens of policy manoeuvres, we suggest gender quotas, accompanied by strategy designed to develop leaders’ gender competency and change agency, are required to support more sustainably equitable work structure within the academy.

Introduction

In this paper we identify how gender bias prevents women from being considered academic experts, and from achieving access to senior positions wherein they might act as change agents to address the gendered academic culture. In response, it is argued that gender quotas could be introduced to derail a ‘circulatory’ system of gender inequity in higher education. However, a plastic reading of equity policy over the last 40 years affords us the opportunity to identify how discourses of human rights and equal opportunity, which informed gender equity policy in Australia in the 1970s and 1980s, have been re-shaped by neoliberalist discourses of individualism and diversity management. This discursive manoeuvre serves to invisibilise structural impediments to gender equality and ‘individualise’ solutions to perceived problems. Within this discursive terrain, gender quotas alone will fail to challenge the systems of thought on which the gendered structures of academia are based. Therefore, harnessing the notion that policy discourse is dynamic and transient, we contend that the current wave of neoliberal discourse can be re/shaped by ‘actants’ (Bennett Citation2010). We also accept Ulmer’s (Citation2015) position that material change is more likely to be achieved if desired policy (an introduction of gender equity quotas) is aligned to an established discourse within which a problem has been generally accepted, and a solution offered. We thus propose that the full implementation of gender quotas (the material change) is reliant on university leaders’ gender competency and change agency, which has capacity to expose existing discourses and policies that propagate gender inequity and support systematic change. More specifically, we posit that engaging gender competency through visibilising and addressing both numerical gender inequity and deeply entrenched beliefs and cultures, will work symbiotically with gender quotas to effect material change within university contexts. Cognisant that gender change agency may be difficult to facilitate, we finally provide examples of strategies of successfully implemented gender equity strategy.

Context: gender inequity in Australian universities

Australia's international gender gap ranking for women’s economic and political participation and opportunity worsened from 15th position in 2006 to 26th in 2023, though 38th for Economic Participation and Opportunity (World Economic Forum Citation2022). Relatedly, the national gender pay gap of 12 per cent means that as of November 2023, the full-time adult average weekly earnings was $1982.80 for men and $1744.80 for women. So, for every dollar on average men earned, women earned 88 cents, or $238 less than men each week, or $12,376 per year. This means that women needed to work two extra months (56 more days) after the end of 2022–2023 financial year to reach the average annual earning of Australian men (Workplace Gender Equality Agency Citationn.d.). Such disparity of participation and opportunity for women in Australia is reflected in the staffing of Australian universities. Whilst there have been significant improvements in women academics inclusion and career success since the mid-1980s when women comprised 20 per cent of academic staff and held only 6 per cent of senior positions (Winchester and Browning Citation2015), in 2020, there were still only 10 women chancellors and 10 women vice chancellors in Australia (less than a quarter in each category), while there were as many as six male chancellors with John as a first name (Ross Citation2020).

Sandy O’Sullivan (Citation2019) reminds us that although there are no specific statistics on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in the academy, the number of all Indigenous academics at both Level A, the entry level lecturing role, and Level E, the most senior professorial position, were lower per capita in 2018 than they were in 2001. This means that in a generation the amount of Aboriginal academics entering the workforce and those reaching the highest level within the academy have remained static (O’Sullivan Citation2019). According to Savigny (Citation2014), if current trends continue, it will take 119 years for women to reach the same number of academic promotions and appointments as men in the professorial ranks. This estimate is even higher for women who face intersectional challenges, including women with caring/parental responsibilities. For instance, a European based study found that the strongest factors determining the achievement of a full professorship stem from academic transitions early in the academic career (ladder) which are more difficult to attain for women academics who are childbearing/rearing at this crucial time (Ooms, Werker, and Hopp Citation2019). Relatedly, academic excellence is linked to geographic mobility, as academics are expected to spend periods at different universities, spanning other countries to be considered favourably for tenure and promotion, which creates additional barriers or challenges for women with caring responsibilities (Ivancheva, Lynch, and Keating Citation2019). Correlatively, people who achieve permanent academic positions are disproportionately care-free, where 75% of women research fellows and 62% of women professors in Germany were child-free in 2006; and women research fellows, as well as women professors, were also more likely than men to remain child-free throughout their careers, as almost twice as many tenured female professors in German universities have no children compared with men (Bomert and Leinfellner Citation2017).

In addition, and regardless of women academics’ caring or parenting status, there are multifarious cultural influences that contribute to women academics being allocated more collegial duties such as teaching, administrative and pastoral responsibilities, which tend to be less valued than research (Manfredi Citation2017). Specifically, data responses from nearly 19,000 academics across 143 colleges and universities indicate that a gendered distribution of academic work negatively impacts women’s productivity and leads ‘directly to salary differentials and overall success in academia’ (Guarino and Borden Citation2017, 690). Concomitantly, students expect greater pastoral support from women professors and hold them to both gendered and higher standards than men professors:

Aside from contributing to burnout and taking time away from career-enhancing activities, greater demands and special requests from students may affect female professors’ career advancement by causing them to get less favourable course evaluations or even more complaints filed against them. (El-Alayli, Hansen-Brown, and Ceynar Citation2018, 147)

Additionally, whilst it is suggested that women academics’ sub-performance in research contributes to their relative under-representation in academic leadership, analysis of more than 3923 authors and 2853 publications covering a wide range of different scientific fields, failed to find any significant difference between citation rates of male and female researchers (where citation is used as a proxy for impact) (Nielsen Citation2016). This research substantiates earlier findings related to gender bias where managers were found to favour male employees over equally performing female colleagues (Castilla and Benard Citation2010) and Wennerås and Wold’s (Citation1997) study where women needed 2.5 times more publications than their male colleagues to be successful with their medical research grant scheme applications. Finally, Nielsen (Citation2016) observes that regardless of general research equivalence in achievement between genders, the increasing dependence on allegedly objective and gender-neutral measures of individual scientific performance are in fact gendered, as career breaks and periods with lower productivity output due to childcare responsibilities are not included in bibliometric assessments. Thus, seemingly neutral and meritocratic processes, the outcomes of which inform the appointment of senior research positions, are inherently gendered, and covertly exclude women from leadership roles.

Relatedly, despite that presenting at conferences can support academics to establish professional networks and academic credibility, most conferences and symposia provide fewer presenting opportunities to women than men (Black et al. Citation2020). Walters' (Citation2018) analysis of international academic conferences, congresses, or symposia for tourism, hospitality and event organization found that of the 230 Keynote Speakers, Invited Speakers, and Expert Panel members identified, just 30% were women, despite that 49% of conference attendees identified as women. Walters concludes that the profiling of men as disciplinary experts inhibits women’s promotion and career progression into senior academic positions (Citation2018). Moreover, sidelining women academics through the promotion of males limits the development of new knowledge in the academy (Walters Citation2018). As West and Curtis (Citation2006, 5) explain, ‘when women are missing … the research questions they would raise are not asked and the corresponding research is not undertaken … higher education suffers’. Women’s lack of opportunity to publicly showcase their knowledge and expertise thus results in both epistemic injustice and a disproportionate number of women professors and senior managers in the academy. This, in turn, provides men with greater opportunity to inform institutional policy development, including equity, diversity and inclusion policy, even when they are less likely to be personally affected by the very issues the policies are developed to address (Anicha, Bilen-Green, and Green Citation2020).

Given the multifarious, inextricably linked, and self-reinforcing barriers to women academics’ career progression, it is unsurprising that whilst women make up the majority of university workforce and approximately equal number of graduates with a PhD (Lindhardt and Berthelsen Citation2017) according to the latest data available (as of May 2024) 61.6% of Australian based academics classified as ‘above senior lecturer’ were male, and 38.3% female (1% were indeterminate intersex) (Australian Government Department of Education, n.d.). Yet, women are available and qualified to adopt academic leadership roles, they are simply not provided the same opportunity as males. Shepherd’s research (Citation2017) found little difference between men and women in terms of their aspirations to secure a more senior university management job. Female deans and heads of school are almost as likely as their male colleagues (43% compared to 45%) to consider applying for a PVC post – the next rung up the management ladder, and a higher proportion of women (29%) than men (22%) say they are very likely to apply. Additionally, when it comes to translating aspiration into action there is still relatively little difference between the genders: 14 per cent of female deans and heads of school, compared to 16 per cent of men, had already applied for a PVC job in their own institution.

As there is no shortage of available and interested women for academic leadership, or a ‘pipeline’ issue as has been suggested, there are instead gendered barriers to academic women’s leadership opportunities. Purposeful strategy designed to derail the vicious cycle of gendered dis/advantage is therefore necessary; one of the most empirically effective strategies of which is the introduction of gender quotas in senior organizational roles, where women leaders act as role models to support institutional transformation (Ní Aoláin, Haynes, and Cahn Citation2011).

A plastic Reading of the capacity to be role models and gender equity change agents

Sealy and Singh (Citation2006) posit that people's career aspirations are influenced by their past experiences and the role models or leaders with whom they identify. These role models are most often people who share similar identities, including the same or similar gender, race, social class, and accents as the individual. Yet the lack of women role models in leadership positions perpetuates gendered structures and reinforces homophilic leadership styles and composition (Sealy and Singh Citation2006). To create an organizational culture where women are seen as capable of leadership, women need to be appointed to leadership positions, which can further inspire other women to develop leadership aspirations and expand conceptions of leadership capabilities and practices (Sealy and Singh Citation2008). However, research warns that having only one or two ‘token’ women leaders limits their ability to influence organizational structures. Similarly, Donaldson and Emes (Citation2000) estimated that only when women comprise 40% of leadership roles, will they have a strong enough voice to achieve full organizational change.

Thus, a significant percentage of women in academic leadership positions in Australian universities is needed to facilitate a culture of aspiration for women academics and those with whom they interact, to redefine who or what a professor or leader is/can be, and help to address gender biases that reinforce women’s subordinate status in the academy. In response, we propose that affirmative action is required to support the appointment of women to leadership roles to break the self-reinforcing cycle of gender bias and women’s relative lack of career success in the academy. Specifically, we recommend the introduction of gender equity quotas for senior management positions.

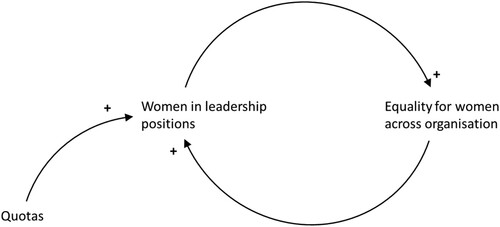

The underlying assumption behind the implementation of quotas to support gender equity is illustrated in . The figure uses the notation from causal loop diagrams (Sterman Citation2000) to show the expectation that as numbers of women in leadership position increase (resulting from quotas), so too will equality for women across the organization more broadly. Similarly, there is reinforcing relationship between improved equality across the organization and numbers of women in leadership positions, given the improved pipeline for women to enter senior positions.

Figure 1. Underpinning assumption behind gender quotas as a strategy to achieve gender equality.

Note, a positive symbol (+) reflects that as one variable increases, the related variable also increases, creating a reinforcing relationship.

While the proposed relationships between these variables, as outlined in , is simple and logical, we suggest it is overly simplistic, given the knowledge that universities are complex systems (Rouse Citation2006; de-identified), operating within wider dynamic political, regulatory and social environments. Within complex systems, outcomes emerge from the interactions between multiple system components, across micro, meso and macro system levels. Thus, the assumption underpinning the impact of quotas fails to consider wider structures, cultures and discourses underpinning academic policy and senior level decision-making. Therefore, a systems-led understanding of gender inequality in higher education can be informed by a plastic reading of policy discourse over the last 40 years to demonstrate a shift from discourses of equal opportunity towards notions of individualism and managing diversity; highlighting the danger that gender quotas might be used to support individual (usually entrepreneurial) women only and fail to fulfil their transformative potential.

Plasticity sits within a broader ideological scaffold of new materialism and the philosophical landscape of posthumanism. Posthumanism frames social phenomena as produced from a series of complex relations by moving away from empirical models of science that seek to determine causality, reliability, and validity, toward material ways of thinking where situatedness, material inter – and intra-connectedness and processes are considered (Ulmer Citation2015). This framework considers that all entities/materialities emerge through an interplay with/in other matter.

We thus specifically adopt Catherine Malabou’s philosophical concept of plasticity (Malabou Citation2010) to consider how gender equity policy and practice are re/shaped by discourses in and around higher education, accepting that material change is more likely if the desired policy (such as an introduction of gender equity quotas) is aligned to an established discourse and solutions offered (Ulmer Citation2015). The theory of plasticity works with the premise that all material, including people, policy statements, and discourses can create and reshape form/s (Ulmer Citation2015). As an available heuristic, then, we understand that materiailities (including academic argument, policy documentation, academics …) each have a capacity to shape ideas and intra-related action. Finally, a plastic lens provides a ‘macro’ and ‘historical’ view of gender equity policy shape and shaping which is obscured if one looks only at policy from the perspective of the current discursive terrain. A macro lens to policy discourse can thus help to identify the transience of discourse and empower actants to deliberately engage in policy re/formation. More specifically, plastic readings of policy discourses contribute new scholarly understandings regarding the shape and movement of educational policy formation (Ulmer Citation2015).

Affirmative action supports the human right of gender equity

Affirmative action falls within the discursive framework of gender equity as a human right, encased in policy and legislation. ‘Equal rights of men and women’ are a fundamental principle of the United Nations Charter, and discrimination based on sex is prohibited under almost every human rights treaty. Specific to Australia, the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) recognizes that women experience inequality in many areas of their lives, including that ‘at work, women face barriers to leadership roles’; identifying that organizations should take all reasonable steps to prevent sex discrimination (Australian Human Rights Commission Citationn.d.). They further identify that special measures or affirmative action can be implemented to ‘foster greater equality by supporting groups of people who face, or have faced, entrenched discrimination so they can have similar access to opportunities as others in the community’ (Australian Human Rights Commission Citationn.d.). Whilst the AHRC fails to identify specific strategy to fostering gender equality, gender equity quotas are the most effective form of affirmative action to achieve equal employment opportunity for women by removing the barriers in the workplace which restrict employment and promotion opportunities for women (Strachan, Burgess, and Sullivan Citation2004)

Quotas are a policy tool intended to address/dismantle systematic over or under-representation of certain groups or practices within organizations. They typically establish a fixed minimum or maximum number of individuals from a particular group who are permitted to hold a particular position or perform a particular role (OECD Citation2015). Quotas are generally mandatory, specific, and have measurable objectives that are set and externally evaluated by governments or industry regulatory bodies, to enhance the economic empowerment of women throughout society by eliminating inequality that has persisted over time (OECD Citation2015).

A major advantage of gender quotas is their ability to restrict homosocial recruitment practices and the preferential promotion of men within ‘old boys’ networks, which prevent women’s equal opportunities to reach management positions based on their gender. Empirical evidence suggests that gender equity quotas are the most effective means of achieving gender balance, as supported by empirical evidence (Ní Aoláin, Haynes, and Cahn Citation2011). Indeed, Forman-Rabinovici, Mandel, and Bauer (Citation2023) found that in countries with quotas the average percentage of women on academic boards is around 23% higher than in countries without, and that women’s presence on academic boards can contribute to gender equality. Quotas therefore provide a potential solution to address gender imbalances in the professoriate. This position, at first glance, finds alignment with the current ‘pulse’ of the nation.

Correspondingly. there is growing acceptance of the need for gender equity strategy across Australia. Evans' (Citation2018) national survey of 2,122 Australians found that 88 per cent agreed that inequality between women and men remains a problem and most Australians strongly align with the need for ‘concerted policy action on gender equality issues both in the workplace and more broadly in society’. In response, the State Government of Victoria developed gender equality law for the first time in Australian history to proactively progress gender equality. The Gender Equality Bill (2018) allows Victorian Government departments, to achieve gender equality through implementing quotas, action plans and reporting (Premier Victoria Government Citation2018).

However, whilst there appears to be a logical argument and growing support for gender equity action in the Australian academy, a plastic reading of higher education policy discourses demonstrates that neoliberalist notions of individualism and responsibilisation rupture equal opportunities discourses and in doing so reconfigure both their form and potency.

Neoliberalism and the transfiguration of equal opportunity discourse

From the mid-1970s anti-discrimination legislation, based on the recognition of women’s increasing workforce participation but unequal position in that workforce, was enacted at the federal level and in all states (Strachan, Burgess, and Sullivan Citation2004). This and subsequent equal opportunity (EO) policy emerged through and are entangled with other policy informing discourses and practices such as collectivism and trade unionism (Strachan, Burgess, and Sullivan Citation2004). During the 1970s and 1980s Australian ‘femocrats’ mobilized the discourse of EO to develop a legislative and policy framework of gender equity reform, and to create a national gender equity infrastructure (Blackmore Citation2006). The framework, based on a commitment to anti-discrimination and affirmative action, was galvanized by collectivist ‘bottom up’ political and trade union activism (Blackmore Citation2006).

Yet throughout the 1990s both the policy development process and the corresponding EO legislation were impacted by significant changes in the Australian industrial relations system. First, the enforcement of EO policy changed from a system of conciliation and arbitration to the development of a ‘heterogeneous and fragmented system that emphasises workplace bargaining’ (Strachan, Burgess, and Sullivan Citation2004, 197). Enterprise bargaining, introduced in Australia in 1991, is a process whereby wage and working conditions are negotiated at the level of the individual organizations. Its introduction decentralized industrial relations and was concomitantly reconfigured by and helped to reinforce dominant neoliberalist discourses such as individualism and managerialism. Consequently, the collectivist and externally driven EO programmes which focused on systematic change, and that had been managed by federal and state policy and legislation, began to be replaced by ‘managing diversity’ (MD) programmes, administered through individual organizations’ human resource (HR) policy, and based on a neoliberalist ideology.

Neoliberalism’s infiltration into higher education

Neoliberalism is a set of policies and beliefs that prioritize free market competition and individualism based on notions of efficiency and meritocracy. In the Australian higher education system, the impact of neoliberal economic and political ideologies is demonstrated by increased student enrolment and decreased public funding, resulting in higher student-to-staff ratios, and a rise in casual employment within academic institutions. An emphasis on economic rationality has also resulted in corporatised university systems focused on international competitiveness, and internal efficiency and accountability; where academics are pressured to demonstrate ‘productivity’ and success through standardized research performance indicators including publishing in high impact journals, external grant income, and journal citation indexes. Such a logic, and related governance structures, led to an imaginary of individual responsibilisation (Giddens Citation1994), where ‘self-regulating subjects’ become responsible for their own achievement, rendering invisible the asymmetry and inequity within higher education (de-identified, 2022).

Neoliberalism both promotes and legitimizes individualism through the discourse (and guise) of meritocracy, or the notion that academic success and recognition are based solely on individual’s talent, effort, and ability, where merit is positioned as neutral and disinterested. Yet, notions of merit and its constituent elements are constructed by academics who most personally benefit (Van den Brink and Benschop Citation2012). Meritocracy has more specifically been critiqued for ignoring the structural disadvantages that prevent some marginalized groups from achieving the narrow and exclusionary criteria of academic ‘merit’ and its rewards (Van den Brink and Benschop Citation2012). Consequently, it can be argued that meritocracy does not consider the unequal distribution of time that people with different genders have (to pursue academic productivity), which perpetuates and amplifies existing inequality and reinforces gender discrimination.

Correspondingly, neoliberal ideas (and processes) of individualism place blame on women themselves for their lack of relative academic career success and offer remedial professional development aimed at changing them, rather than challenging an unjust system. Such approaches legitimise unequal rewards, promote individualistic self-interest and entrepreneurial values, and further entrench responsibilisation. Relatedly, Tzanakou and Pearce (Citation2019) argue that universities address gender inequality through an individualistic neoliberal stance that positions female liberation as achievable exclusively through individual choice and competitive endeavour.

The pervasive nature of neoliberal ideas of individualism have also infiltrated and reshaped discourses of equal opportunity (EO). Enveloped within neoliberalist ideology the discourse of managing diversity (MD) extols the virtues of ‘individual difference’ and ‘equality or fairness of treatment’ to both obscure structural inequalities and circumvent equity programmes (Bacchi Citation2000). The focus of MD also ties ‘diversity’ to organizational objectives such as productivity. Since the mid-1990s, the discourse of MD has been mobilized as ‘better for business’ and ‘in the national economic interest’ (Sinclair Citation1998). Correspondingly, Bartz et al. (Citation1990) note that MD policy statements stress that differences among employees, if properly managed, are an ‘asset’ to work being done more efficiently and effectively. This discourse, for Ahmed (Citation2012), demonstrates an avoidance of explicit discussions of gender (in)equality and reflects a depoliticized neoliberal standpoint. Here, organizational discussions of equity and diversity conjure an ‘illusion of equality’ by focusing on how ‘everyone’s different’, while effectively ignoring how those differences intersect with structures of power and oppression (Ahmed Citation2012). Finally, the language of diversity can actively hinder equity change as it lacks clearly defined endorsed goals and legislation to ensure compliance, making language statements and policy a proxy for action.

Analysis of the infiltration of neoliberalist ideological technologies and dispositions into higher education demonstrates how the discourse of equal opportunity has been transfigured into neo-liberalised imperatives for managing diversity; where the perception of fairness is favoured over the action needed to support fairness. Similarly, self-responsibilisation and the concept of merit invisibilise gender and other collectively experienced social locations, resulting in notions, and related policy, that female liberation can be achieved through individual actors (Tzanakou and Pearce Citation2019).

Consequently, it is most often the women who have adopted the dominant, taken-for-granted cultures of a masculinized performativity in universities that are accepted as academic leaders (Van den Brink and Benschop Citation2012). Ergo, within a neoliberalist milieu, quotas alone are likely to benefit predominantly self-entrepreneurial and striving women, leaving the structures that support and normalize gender inequity, unchecked. Indeed, systems that fail to examine the hegemonic order will do little to dismantle the basis of that hegemonic order.

This is borne out in the Austrian higher education system when legislation was introduced (in 2009) requiring all committee and senior roles appointed by university senates to fulfil a quota of female members. Whilst the quota requirement resulted in the percentage of women in rectorate positions reaching 49% by 2019, the percentage of women full professors did not improve accordingly (at only 25% in 2018). The lack of ‘trickle down’ of women’s success illustrates a ‘discrepancy between numeric and substantive representation’ (Wroblewski Citation2021, 4). Similarly, Cuthbert et al. (Citation2019) problematize focusing solely on achieving gender parity or numeric equality as it leaves the systematic barriers to sustainable gender equality untroubled. In response, the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Research has subsequently introduced further policy aimed at supporting ‘gender competence’ in all higher education processes. Correspondingly, Lisa Kewley (Citation2021, 616) identified that whilst introducing gender quotas are necessary to achieve short term numeral equality, gender quotas alone will not sustain gender equality in the academy. Thus, whilst in Australia, the National Health and Medical Research Council recently introduced gender quotas for allocation of highly competitive mid-career and senior fellowships (Nogrady Citation2022), the peer review criteria have been retained without gender competency training for reviewers, it may be that the new policy will only provide opportunities to women (and non-binary) academics who successfully meet traditional, (arguably androcentric) merit-based criteria.

We therefore suggest that gender quotas, that have potential to address numerical inequality, need to be accompanied by strategy designed to support university leaders’ gender insight and change agency, to maximize their capacity to facilitate organizational change. Such an approach moves beyond ‘equality for individual women’ to supporting a ‘project of transformation for organizations’ (Cockburn Citation1989, 218). A focus on gender insight and change agency, which examines examples and impact of gendered biases in policy and practice, and provides opportunities for leaders to identify and collaboratively address equity strategy and intervention, can transforms the commonly adopted ‘traditional’ gender intervention of professional development for women, into a platform for consciousness raising and transformative change (De Vries and Van den Brink Citation2016).

Whilst any gender equity strategy should be tailored to the specific needs of each institution, there are several methods that might be adopted, adapted, and amalgamated to rupture the (plastic/impermanent) hegemonic order which informs the shape and longevity of gendered systems (of thought and practice) in the academy. For instance, De Vries and Van den Brink’s (Citation2016) approach involves providing professional development to women leaders to increase their awareness of the gendered nature of their institution, alongside identifying gaps between gender equity policy and practice, promoting flexible work practices, resisting devaluing part-time staff, facilitating generosity over competitiveness, and standing up to unreasonable demands. However, this approach requires women leaders to identify and advocate for change, perpetuating the notion that gender equity and structural change is the responsibility of women.

A second strategy, therefore, that complements professional development for women, involves instituting a male champions of change strategy. Whilst contested, with Kelan and Wratil (Citation2018) noting that notions of male championship connote ‘heroic’ masculinity and facilitate men taking charge and receiving credit for addressing inequality, it’s generally a truism that men in leadership positions have ‘enhanced credibility and positional power to confer approval for a cause, create accountability … that promote that cause over a sustained period’ (Nash et al. Citation2021, 3). Male allies in positions of influence over strategy development and implementation are thus a wasted resource if they are not engaged in gender equity allyship. Further, because male allyship potentially perpetuates the status quo with men taking leadership positions in equity committees and policy development, it’s crucial that potential male allies engage in professional development that builds gender and structural change competence by facilitating them to develop a sophisticated understanding of gendered inequality, including their own privilege, whilst providing impetus for them to highlight and champion marginalized Others similarly involved in advocacy and activism. A third strategy that might be considered seeks to reshape neoliberalist and individualist frameworks of thinking, as well supporting women’s consciousness raising involves feminist mentoring (Harris Citation2022). In contrast to traditional (individualized and neoliberalist) feminist mentoring considers all aspects of a woman’s life and provides alternative models of ‘success’ to prevent women being assimilated into male-dominated work cultures (Harris Citation2022). Indeed, as identified earlier, individualizing and self-responsibilising women’s career development, invisibises gendered structural barriers that impact all women and gender diverse academics. Thus, feminist mentoring can be employed to both highlight and address systematic barriers to women’s success whilst simultaneously supporting individual women to be change agents and leaders. Finally, feminist mentoring could also be offered to male academics, to facilitate their gender competency and reflect on their own positionality and conceptualisations of leadership.

Additionally, a gender equity programme might include integrated peer and vertical mentoring alongside role modelling, focusing specifically on the needs of women, such as that which was employed in the field of emergency medicine (Welch et al. Citation2012). Women participants in the programme identified that they experienced feelings of camaraderie, belonging, and inclusiveness, but also co-identified strategies to support work-life balance for women emergency medicine faculty and women emergency medicine specialists. These included a paid family leave policy, nominating women for awards, and encouraging academic collaboration, and advocacy for lactation spaces in emergency departments at two hospitals (Harris Citation2022). Relatedly, Petrucci’s (Citation2020) research on gender-inclusive meetups in the tech industry identified that issues raised at the meet up by women and nonbinary persons led to the introduction of gender-neutral wording in job advertisements which actively encourage women and nonbinary persons to apply.

Finally, Bertrand Jones et al. (Citation2020) share the experience of participants involved in the culturally responsive mentoring programme for emerging Black women academics in the US. Qualitative findings determine that its distinctiveness lay in a combination of cultural sensitivity and relationality, centred on their lived experiences. The programme supports participants’ research capacity through collaborative research approaches whilst relationship building facilitates opportunities to share and identify strategy that address challenges which arise from the intersections of race and gender (Bertrand Jones et al. Citation2020). Such culturally responsive mentoring might also assist Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and gender diverse academics in Australia by providing non-competitive and collectivist ways of working that expose and challenge neoliberal subjectivities including the concept of a neutral and benevolent meritocracy.

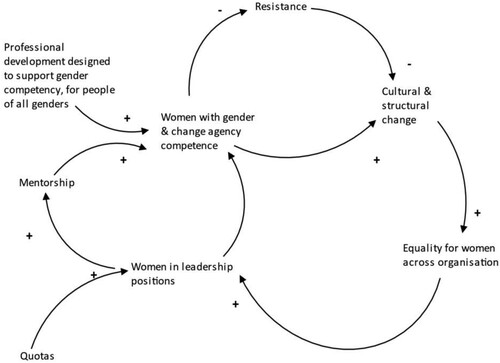

These gender equity strategies, understood in relation to the success yet limitations of gender quotas, demonstrate that changing the composition of university leadership alone is not enough to affect structural or cultural organizational change. We thus suggest that a combination of gender quotas, PD programmes, and various forms of mentorship can facilitate both numeric and substantive gender equality, by moving beyond supporting individual women. The suite of strategies (or aspects thereof) identified above can also challenge conceptualisations of neoliberal subjectivities including the criteria of academic merit, the notion that women academics are homogenous so need the same support or strategy to define and achieve career success and address the misconception that gender equity is women’s responsibility, to provide a comprehensive and sustainable approach to addressing gender inequity in the academy. Importantly, gender competence can also assist to manage resistance to gender equity from those (of any gender) who have achieved success within existing system structures and cultures. For example, the recent publication by Abbot et al. (Citation2023) criticizes the use of quotas and calls for a return to a focus on ‘merit’ combined with improved education and mentoring for disadvantaged groups. Resistance is inevitable in any change process, and acts to balance or dampen the strength of reinforcing relationships between variables. It is hoped that through adopting or adapting the strategies we suggest (and others yet to be explored), collaborative and systemically adopted solutions can be found. Yet, given the porosity of higher education institutions, which are re/shaped by broader cultural belief systems, complementary solutions are likely to be required beyond universities themselves, to support policy and discursive shifts away from neoliberalist funding models that require competition amongst academics and institutions (that promote individualism and self-responsibilisation). Managed well, such solutions should result in an academic system that fulfil its roles of delivering quality research and educational outcomes, whist fostering collaboration and fulfilling a commitment to civic values including gender equality.

To summarize, we propose a model to support gender equality, taking a more holistic complex systems approach (illustrated below in ). The causal loop diagram demonstrates how strategies beyond quotas can increase the number of women in leadership with gender and change agency competence, supported by male allies, who can affect the cultural and structural change required to address barriers to gender equity impacting women across the organization. We nevertheless posit that future work should aim to engage the wider sector and identify additional systemic strategies to support effective change.

Figure 2. Causal loop diagram for achieving gender equality.

Note, a positive symbol (+) reflects that as one variable increases, the related variable also increases, creating a reinforcing relationship; a negative symbol (-) reflects that as one variable increases, the related variable decreases, creating a balancing relationship.

Concluding thoughts

There is evidence of widespread, longitudinal gender inequity in Australian universities. It is particularly apparent in the composition of leadership and senior roles. Therefore, whilst there has been significant improvement in academic women’s career opportunities since, the 1980s, when women comprised 20 per cent of academic staff and held 6 per cent of senior positions, these improvements required support for gender equality from the most senior academic levels, the setting and monitoring of targets, and research that both enables and tracks the effectiveness of intervention strategies (Winchester and Browning Citation2015). Gender quotas have been recommended as a useful strategy to continue the progress made; progress that has recently stalled (Ruggi and Duvvury Citation2023). In support of this intervention Stephen-Norris and Kerrissey (Citation2016, 242) argue that ‘interventions are crucial components of any plan to increase women’s access to jobs that historically have been dominated by men’, and Gouthro, Taber, and Brazil (Citation2018) assert that once women are present in higher levels in academe, it may be that this will become the new ‘norm’ and mental models or accepted beliefs of what a successful academic or a strong researcher looks like will begin to shift.

However, an analysis of gender equality policy discourses over the last 40 years demonstrate an infiltration of neoliberalist ideas serve to individualize both the problem and the solution. Within such a culture, gender equity interventions, including gender quotas, might simply be assimilated into an ‘add women and stir’ approach to addressing gender inequity leaving the hegemonic order which maintains the structure intact. Therefore, a strategy that both disrupts the gender composition of leadership in higher education (via equity quotas) accompanied by a programme in which leaders critically examine the dominant, taken-for-granted discourses and hegemonic structure that helped to establish and maintain gender bias in universities, with which leaders of all genders participate, are required to support both short and long-term gender equality.

Finally, a plastic reading of gender equity discourse in higher education illuminates the malleability of policy discourse and facilitates researchers to adopt a critical distance to tangible present conditions. It also allows us to reject notions of the ‘inevitability’ and ‘acultural’ and ‘ahistorical’ nature of neoliberalist ideas, and helps to disrupt the political inertia that accumulates when one holds on to ‘the present as the only option and as being without alternatives’ (Tiainen, Leiviskä, and Brunila Citation2019, 7a). Rejecting the inevitability of neoliberalism is essential if we are to focus on the structural impediments to gender equity, envision potential solutions to its causes and consequences, and plan and debate the form/s of such strategy. We additionally accept Ulmer’s (Citation2015) position that material change is more likely to be achieved if desired policy (such as an introduction of gender equity quotas) is aligned to an established discourse within which a problem has been generally accepted, and a solution offered. By identifying the problem as an ideological manoeuvre, via neoliberalism, towards individualism and self-responsibilisation we offer the solution to be gender quotas complemented with a strategy to support gender competency and collaborative/systematic change agency.

Furthermore, reviewing gender equity strategy through a ‘plastic’ perspective, combined with a complex systems perspective, provides insight into how malleable systems that are often presented as statice, can be, and highlights how potentially radical interventions such as gender quotas might be assimilated into and serve to propagate a gendered system. Adopting such methodologies to policy analysis can therefore provide impetus to identify and challenge structures of inequity, that are conceptualized as dynamic, and help us to design equity interventions that are less easy to blunt by neoliberalist, assimilative discourses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gail Crimmins

Gail Crimmins is an Associate Professor in Communication at the University of the Sunshine Coast, gender equity and diversity scholar, and member of the National SAGE Athena Swan Advisory Committee. Gail designs programs and advocates for policy to develop leaders' gender competency and change agency to support the development of more equitable work structures and opportunities within universities.

Elvessa Marshall

Elvessa Marshall, is committed to social justice and has led state-wide programs and projects within primary mental health care, disability, cancer screening and prevention, and organisational wide gender equity, diversity, and inclusion initiatives. With over 20 years of experience in data informed project design, implementation and impact assessment, Elvessa has led a wide range of projects that embedded evaluated research into practice, and projects which generated evidence where a gap existed. With areas of expertise including equity and application of intersectional approaches, Elvessa co-led the development and implementation of the University's inaugural Diversity and Inclusion Plan and currently leads the University's strategic gender equity program.

Gemma J.M. Read

Associate Professor Gemma J.M. Read is the Director of the Centre for Human Factors and Sociotechnical Systems at the University of the Sunshine Coast. She received her PhD from Monash University and has over 16 years' experience applying human factors and systems thinking to improve safety, performance and wellbeing in organisations and broader societal systems.

References

- Abbot, Dorian., A. Bikfalvi, A. L. Bleske-Rechek, W. Bodmer, P. Boghossian, C. M. Carvalho, J. Ciccolini, et al. 2023. “In Defense of Merit in Science.” Journal of Controversial Ideas 3 (1): 1. https://doi.org/10.35995/jci03010001.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2012. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Anicha, Cali, Canan Bilen-Green, and Roger Green. 2020. “A Policy Paradox: Why Gender Equity is Men’s Work.” Journal of Gender Studies 29 (7): 847–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2020.1768363.

- Australian Human Rights Commission. n.d. Gender Equality. https://www.humanrights.gov.au/quick-guide/12038#fn3.

- Bacchi, Carol. 2000. “The Seesaw Effect: Down Goes Affirmative Action, Up Comes Managing Diversity.” Journal of Interdisciplinary Gender Studies 5 (2): 64–83.

- Bartz, David E., Larry W. Hillman, Sande Lehrer, and Gilbert M. Mayburgh. 1990. “A Model for Managing Workforce Diversity.” Management Education and Development 21 (4): 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/135050769002100406.

- Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bertrand Jones, Tamara, Jesse R. Ford, Devona F. Pierre, and Denise Davis-Maye. 2020. “Thriving in the Academy: Culturally Responsive Mentoring for Black Women’s Early Career Success BT.” In Strategies for Supporting Inclusion and Diversity in the Academy: Higher Education, Aspiration and Inequality, edited by G. Crimmins, 123–140. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Black, Ali, Gail Crimmins, Rachael Dwyer, and Victoria Lister. 2020. “Engendering Belonging: Thoughtful Gatherings with/in Online and Virtual Spaces.” Gender and Education. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09540253.2019.1680808.

- Blackmore, Jill. 2006. “Deconstructing Diversity Discourses in the Field of Educational Management and Leadership.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 34 (2): 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143206062492.

- Bomert, C., and S. Leinfellner. 2017. “Images, Ideals and Constraints in Times of Neoliberal Transformations: Reproduction and Profession as Conflicting or Complementary Spheres in Academia?.” European Education Research 16: 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116682972.

- Castilla, E. J., and S. Benard. 2010. “The Paradox of Meritocracy in Organizations.” Administrative Science Quarterly 55 (4): 543–676. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.4.543.

- Cockburn, Cynthia. 1989. “Equal Opportunities: The Short and Long Agenda.” Industrial Relations Journal 20 (3): 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2338.1989.tb00068.x.

- Cuthbert, Denise, Robyn Barnacle, Nicola Henry, Kay Latham Leul Tadesse Sidelil, and Ceridwen Spark. 2019. “Barriers to Gender Equality in STEMM: Do Leaders Have the Gender Competence for Change?” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 2040-7149. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-09-2022-0267.

- De Vries, Jennifer A., and Marieke C. L. Van den Brink. 2016. “Transformative Gender Interventions: Linking Theory and Practice Using the ‘Bifocal Approach’.” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 35 (7/8): 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-05-2016-0041.

- Donaldson, E. Lisbeth, and Claudia Emes. 2000. “The Challenge for Women Academics: Reaching a Critical Mass in Research, Teaching and Service.” The Canadian Journal of Higher Education 30 (3): 33–55. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v30i3.183368.

- El-Alayli, Amani, Ashely Hansen-Brown, and Michelle L. Ceynar. 2018. “Dancing Backwards in High Heels: Female Professors Experience More Work Demands and Special Favor Requests, Particularly from Academically Entitled Students.” Sex Roles 79 (3-4): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017.0872-6.

- Evans, Mark. 2018. From Girls to Men: Social Attitudes to Gender Equality in Australia. 50/50 by 20130 Foundation. http://www.broadagenda.com.au/home/from-girls-to-men-social-attitudes-to-gender-equality-in-australia/.

- Forman-Rabinovici, Aliza, Hadas Mandel, and Anne Bauer. 2023. “Legislating Gender Equality in Academia: Direct and Indirect Effects of Statemandated Gender Quota Policies in European Academia.” Studies in Higher Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2260402.

- Giddens, Anthony. 1994. Beyond Left and Right. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gouthro, Patricia, Nancy Taber, and Amanda Brazil. 2018. “Universities as Inclusive Learning Organizations for Women?: Considering the Role of Women in Faculty and Leadership Roles in Academe.” Learning Organization. https://doi.org/10.1108/TLO-05-2017-0049.

- Guarino, Cassandra M., and Victor M. H. Borden. 2017. “Faculty Service Loads and Gender: Are Women Taking Care of the Academic Family?” Research in Higher Education 58 (6): 672–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9454-2.

- Harris, Deborah H. 2022. “Women, Work, and Opportunities: From Neoliberal to Feminist Mentoring.” Sociology Compass 16 (3). https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12966.

- Heffernan, Troy. 2021. “Sexism, Racism, Prejudice, and Bias: A Literature Review and Synthesis of Research Surrounding Student Evaluations of Courses and Teaching.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1888075.

- Ivancheva, Mariya, Kathleen Lynch, and Kathryn Keating. 2019. “Precarity, Gender and Care in the Neoliberal Academy.” Gender, Work and Organization 26 (4): 448–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12350.

- Kelan, Elizabeth K, and Patricia Wratil. 2018. “Post-heroic Leadership, Tempered Radicalism and Senior Leaders as Change Agents for Gender Equality.” European Management Review 15 (1): 5–18, 6. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12117

- Kewley, Lisa J. 2021. “Closing the Gender Gap in the Australian Astronomy Workforce.” Nature Astronomy 5:615–620. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01341-z.

- Lindhardt, Tove, and Connie B. Berthelsen. 2017. “H-index or G-Spot: Female Nursing Researchers’ Conditions for an Academic Career.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 73 (6): 1249–1250. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12942.

- Malabou, Catherine. 2010. Plasticity at the Dusk of Writing: Dialectic, Destruction, Deconstruction. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Manfredi, S. 2017. “Increasing Gender Diversity in Senior Roles in Higher Education: Who is Afraid of Positive Action?.” Administrative Sciences 7 (2). Accessed December 2023. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3387/7/2/19/htm.

- Mitchell, Kristina M. W., and Jonathon Martin. 2018. “Gender Bias in Student Evaluations.” PS: Political Science & Politics 51 (3): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104909651800001X.

- Nash, Meredith, Ruby Gant, Robyn Moore, and Tania Winzenberg. 2021. “Male Allyship in Institutional STEMM Gender Equity Initiatives.” PLoS One 16 (3): e0248373. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248373.

- Ní Aoláin, Fionnuala, Dina Haynes, and Naomi Cahn. 2011. On the Frontlines: Gender, War and Post Conflict Process. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Nielsen, Mathias Willum. 2016. “Gender Inequality and Research Performance: Moving Beyond Individual-Meritocratic Explanations of Academic Advancement.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (11): 2044–2060. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1007945.

- Nogrady, Bianca. 2022. “‘Game-changing’ Gender Quotas Introduced by Australian Research Agency.” Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-03285-4.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2015. Why Quotas Work for Gender Equality. http://www.oecd.org/social/quotas-genderequality.htm.

- Ooms, Ward, Claudia Werker, and Christian Hopp. 2019. “Moving Up the Ladder: Heterogeneity Influencing Academic Careers through Research Orientation, Gender, and Mentors.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (7): 1268–1289. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1434617.

- O’Sullivan, Sandy. 2019. “First Nations’ Women in the Academy: Disrupting and Displacing the White Male Gaze.” In Strategies for Resisting Sexism in the Academy. Palgrave Studies in Gender and Education, edited by G. Crimmins. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

- Petrucci, Larissa. 2020. “Theorizing Postfeminist Communities: How Gender-inclusive Meetups Address Gender Inequity in High-tech Industries.” Gender, Work and Organization 27 (4): 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12440.

- Premier Victoria Government. 2018. Australia’s First Gender Equality Bill: Have Your Say. https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/australias-first-gender-equality-bill-have-your-say/.

- Ross, John. 2020. “Female Leadership Still Lags in Australian Universities.” The World University Rankings. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/female-leadership-still-lags-australian-universities.

- Rouse, W. B. 2006. Universities as Complex Enterprises: How Academia Works, Why it Works These Ways and Where the University Enterprise is Heading. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Ruggi, Lennita Oliveara, and Natta Duvvury. 2023. “Shattered Glass Piling at the Bottom: The ‘Problem’ with Gender Equality Policy for Higher Education.” Critical Social Policy 43 (3): 469–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/02610183221119717.

- Savigny, Heather. 2014. “Women, Know Your Limits: Cultural Sexism in Academia.” Gender and Education 26 (7): 794–809. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2014.970977.

- Sealy, Ruth and Val Singh. 2006. Role Models, Work Identity and Senior Women's Career Progression – Why are Role Models Important? Academy of Management Proceedings, E1–E6. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2006.22898277.

- Sealy, Ruth, and Val Singh. 2008. “The Importance of Role Models in the Development of Leaders’ Professional Identities.” In Leadership Perspectives, edited by James K. Turnbull and J. Collins, 208–222. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shepherd, Sue. 2017. “Why are There so Few Female Leaders in Higher Education? A Case of Structure or Agency?” Management in Education 31 (2): 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020617696631.

- Sinclair, Amanda. 1998. Doing Leadership Differently. Gender, Power and Sexuality in a Changing Business Culture. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Stephen-Norris, Judith, and Jasmine Kerrissey. 2016. “Enhancing Gender Equity in Academia: Lessons from the ADVANCE Program.” Sociological Perspectives 59 (2): 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121415582103.

- Sterman, J. D. 2000. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World. Boston: Irwin McGraw-Hill.

- Strachan, Glenda, John Burgess, and Anne Sullivan. 2004. “Affirmative Action or Managing Diversity: What is the Future of Equal Opportunity Policies in Australia?” Women in Management Review 19 (4): 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420410541263.

- Tiainen, Katarina, Annina Leiviskä, and Kristina Brunila. 2019. “Democratic Education for Hope: Contesting the Neoliberal Common Sense.” Studies in Philosophy and Education 9 February:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-019-09647-2.

- Tzanakou, Charikleia, and Ruth Pearce. 2019. “Moderate Feminism Within or against the Neoliberal University? The Example of Athena SWAN.” Gender, Work & Organization 26 (8): 1191–1211. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12336.

- Ulmer, Jasmine B. 2015. “Plasticity: A New Materialist Approach to Policy and Methodology.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 47 (10): 1096–1109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2015.1032188.

- Van den Brink, Marieke, and Yyvonne Benschop. 2012. “Gender Practices in the Construction of Academic Excellence: Sheep with Five Legs.” Organization 19 (4): 507–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508411414293.

- Wagner, Natascha, Matthias Rieger, and Katherine Voorvelt. 2016. “Gender, Ethnicity and Teaching Evaluations: Evidence from Mixed Teaching Teams.” Economics of Education Review 54:79–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.06.004.

- Walters, Trudie. 2018. “Gender Equality in Academic Tourism, Hospitality, Leisure and Events Conferences.” Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 10 (1): 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2018.1403165.

- Welch, Julie L., Heather L. Jimenez, Jennifer Walthall, and Sheryl E Allen. 2012. “The Women in Emergency Medicine Mentoring Program: An Innovative Approach to Mentoring.” Journal of Graduate Medical Education 4 (3): 362–366. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-11-00267.1.

- Wennerås, C., and A. Wold. 1997. “Nepotism and Sexism in Peer-Review.” Nature 387: 341–343. https://doi.org/10.1038/387341a0.

- West, Martha S., and John W Curtis. 2006. AAUP Faculty Gender Equity Indicators. Accessed April 20, 2023. http://www.aaup.org/NR/rdonlyres/63396944-44BE-4ABA-9815-5792D93856F1/0/AAUPGenderEquityIndicators2006.pdf.

- Winchester, Hilary, and Lynette Browning. 2015. “Gender Equality in Academia: A Critical Reflection.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 37 (3): 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2015.1034427.

- Workplace Gender Equaltiy Agency. n.d. “Promotiong and Improving Gender Equality in the Workplace.” https://www.wgea.gov.au/.

- World Economic Forum. 2022. Gender Global Gap Report. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2022.pdf.

- Wroblewski, Angela. 2021. “Quotas and Gender Competence: Independent or Complementary Approaches to Gender Equality?” Frontiers in Sociology 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.740462. PMID: 34513981; PMCID: PMC8429500.