ABSTRACT

Inspired by posthuman, feminist materialist theory-doings in educational research, this paper maps moments in a post-qualitative research project that set out to explore what else relationships and sexuality education might become with ‘art-as-way’ (Manning Citation2020) in a shaky yet conducive policy context where ‘what matters’ must not be assumed in advance but co-constructed with children and young people. Progressively supported by an artist-in-residence teacher assistant, composer and filmmaker, we open up what unfolds when a diverse group of 11 young people (age 13–14) creatively unbox and make ‘what matters’ to them in an art classroom. We conceptualize what came to matter as ‘dartaphacts’ (arts-activist objects) and follow these other-worldly posthuman pARTicipants as they connect, grow, and become ‘more-than’. We speculate, that in conducive, con-sense-ual environments, the affective power of dartaphacts can unbox a living curriculum for a Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) to come, in all its Majestic Insecurity, Untitled, Freedoms, Feathers, Bruised Hearts, Consent-quakes, eQuality Vibrations and Wiggly Woos.

Introduction: what is mattering?

Matter makes itself felt … matter feels, converses, suffers, desires, yearns and remembers. (Barad, in Dolphijn & van der Tuin, Citation2012, 59)

PhEmaterialist research, harnessing the affective power of the visual arts to ‘agitate’ (Chen Citation2019) the ‘unrest’ (Massumi Citation2017) of what might be mattering in the field of sexuality education has proliferated in recent years (see Allen Citation2020; Lupton and Leahy Citation2021; Blaikie Citation2021; Renold Citation2024; Strom et al. Citation2019). Examples include materializing how gender matters and jars young people (Renold and Ringrose Citation2019); speculative film-making on gender, sexuality and gaming cultures with neuro-diverse young people (Timperley Citation2020); mashing up the sexualization of media advertisements with teen girls in craftivist collaging workshops (Ringrose, Regehr, and Zarabadi Citation2021); composing hashtag activisms on pre-teen sexual harassment (Pihkala and Huuki Citation2019); crafting fruiting-bodies in a queer fungi project with LGBTQ+ young people (Marston Citation2025a); and engaging life-drawing to diffract heteronormative and raced colonial imaginings of the nude female body with young women artists (Stanhope Citation2022). What unites these phEmaterialist projects is that they have crafted and/or coproduced experiential artefacts, or what we theorize below as ‘dartaphacts’, that have taken form (Manning Citation2013), to in-form and trans-form diverse publics, practices and policies. These are projects conducted by PhEmaterialist academics who are not stepping into the onto-epistemological ‘turn’ as ‘off-ground, theory-armed onlookers’. We are, as Stengers (Citation2021, 89) writes, ‘about engagement all the way down’, making ‘activist practices’ and choreographing the political in ways that ‘demand engagement, involving partners for whom such practices matter’. This work is beginning to draw attention to the ethical-political constraints and capacities of becoming response-able (Barad Citation2007) with what is crafted and communicated in projects that centre and problematize gender and/or sexuality in the field of childhood and youth across both conducive and hostile socio-political contexts (Butler Citation2024).

The site of engagement and creative phEmaterialist intra-ventionFootnote2 (Renold and Ringrose Citation2019) for this paper is the making and mattering of Wales’ (UK) Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) curriculum, a lively assemblage that we have become increasingly entangled within. Over the last nine years, Wales has radically overhauled its national curriculum, centred around a series of ‘what matters’ statements (Donaldson Citation2016). In contrast to other national curriculums, there are no detailed learning objectives. Consequently, ‘what matters’ demands significant interpretation. Within this context, the Welsh Government proposed extensive reforms to their outdated, non-mandatory, 2010 Sex and Relationships Education guidance. These reforms were sparked by two reports from a national Sex and Relationships Expert Panel. EJ was invited by the education minister to chair this panel and was tasked with creating a new vision for a future RSE (see Renold and McGeeney Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Through these reports, and subsequent policy and practice assemblages, it was possible to open up the matterphorical (Gandorfer and Ayub Citation2021) concept of ‘what matters’, by introducing the notion of an ‘experience-near’, ‘living curriculum’. A living curriculum, as Snaza and Mishra Tarc (Citation2019, 2) argue, is the opposite of ‘the dead, established and revered text, not as a set of facts, a subject area to be studied, but as onto-epistemological’. For us, taking an onto-epistemological approach to ‘what matters’ (i.e. where being (ontology) and knowing (epistemology) are inseparable) is a mode of attuning to lived experience and knowledge-making as ongoing and ever-differentiating.

Over the following years, the panel’s recommendations informed Wales’ whole school approach to Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE), now statutory for all children aged 3–16 (Welsh Government Citation2022). Key changes included: a shift from ‘sex’ to a more holistic definition of ‘sexuality’; expanding and embedding ‘what matters’ across the full curriculum (from humanities and the expressive arts to science, maths and technology); and a commitment to LGBTQ+ inclusivity, rights and equity. While the notion of ‘experience-near’ RSE did not make its way into the revised 2020 guidance, ‘developmentally appropriate’ RSE was re-defined as a practice that ‘will not assume, but attune to and build upon learners’ evolving knowledge and experience’ (Welsh Government Citation2020, 40). In the final version of the statutory guidance (Welsh Government Citation2022), schools are encouraged to build a ‘relevant and responsive’ RSE by co-constructing ‘what matters’ with children and young people.

Becoming response-able with the materialization of Wales’ new RSE has included coproducing accessible gender and sexuality education resources (see the creative activist toolkit www.agendaonline.co.uk) and an ongoing RSE professional learning programme (see www.agendatonline.co.uk/crush) to support practitioners engage more directly with ‘what matters’ to children and young people. For many years, a conducive context was in full swing (Renold, Ashton, and McGeeney Citation2021). However, when RSE became statutory in 2022 and more noticeable to wider publics, this dynamic RSE assemblage of possibility and potential started to wobble and waver. It came under intense and biased scrutiny, which was used to spread misinformation about the guidance (Ashton Citation2023). Online abuse was also directly targeted at EJ (see Renold and Ivinson Citation2022). These attacks align with the wider sexuality education context in England where statutory RSE is rapidly retreating from what children and young people need and want (Setty and Dobson Citation2023) making research that can attune to, affirm and amplify ‘what matters’ ever more vital (Renold et al. Citation2024a).

Co-creating and reanimating what matters in ways that keep the potential of this new RSE on the move and mattering is what focuses this paper. Across four sections, we glimpse at the unfolding of what became the ‘UnboXing RSE Project’ – a participatory project which worked creatively with the matterphorics of what matters with young people, an artist in residence assistant teacher, a filmmaker and composer over two years. Before we provide readers with the rhizomatic journey of the ‘living RSE curriculum’ that materialized and took flight within and beyond the school, we first introduce our use of ‘art’ and the post-qualitative concept of the ‘dartaphact’. It is a concept that continues to become resourceful in communicating the role of posthuman agency in our arts-activist praxis.

Making way for dartaphacts

Like many post-qualitative arts-informed youth research/ers, the art in our praxis is processual, relational and transformative (for example, see Coleman, Page, and Palmer Citation2019; Harris Citation2021; Hickey-Moody et al. Citation2021; Rosiek Citation2017; Truman Citation2021). Our approach to arts-informed praxis is inspired by Erin Manning’s medieval notion of art-as-way; that is, to conceive art as a passageway to coming to feel/think differently. This is not about utilizing arts-based methods for ‘data’ waiting to be collected or seeking to define art’s value in advance. Rather, it is working creatively with ‘art’s processual capacity to foreground passage and make felt’ (Manning Citation2020, 22). Its value is its force for onward articulation and ongoing connection. Envisioning ‘art-as-way’ is to ‘empirically attuneFootnote3’ (Stewart Citation2014) to the ever-differentiating diversity of the world and imagine a world otherwise. It involves creating ethical-political spaces for registering and surfacing the folds of what might be mattering and for that mattering to move the world (Marks Citation2024). Implicit in our praxis is a responsibility to call out practices which subjugate, silence, sensationalize, simplify and still the ‘qualitative multiplicity’ (Braidotti Citation2010) of children and young people’s experiences; and ‘stay with the trouble’ that comes to matter (Haraway Citation2016) as events materialize (Renold and Ivinson Citation2022). Our concept of the ‘dartaphact’ has accompanied us on this journey to theorize the making of posthuman pARTicipantsFootnote4 for the social sciences.

The concept ‘dartaphact’ mixes the word data, art and act/ivism in processes that make the vitality of mattering affects (Stern Citation2010) and effects of experience available for wider publics to feel and be moved by. The concept is deliberately ambivalent about being an object (artefact) and a verb: the artful making of experiential facts. The first half of the concept – darta – (a fusion of data and art) is an explicit intervention to trouble what counts as social science or school data. Instead, darta emphasizes and values the speculative process of what comes to matter with ‘art-as-way’. The second half of the concept – phact – signals the explicit posthuman ethico-political activist potential of what matter can do – the agentic life force running through all matter. The ‘ph’ at the heart of the concept replaces ‘f’ in dartaphact to register the posthuman facts of life. In many ways, the dartaphacts are our trans*versal posthuman pARTicipants carrying and amplifying what matters throughout the UnboXing RSE project, which we turn to next.

UnboXing RSE with creative agendas

The UnboXing RSE project became a two-phased exploratory strand of a Wellcome-funded public engagement project. The larger project was tasked with opening and informing past and future cycles of the UK National Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (natsal) survey and survey data (we unpack the connection below). The first phase of the project adapted a range of ‘stARTer’ activities from the AGENDA resource (www.agendaonline.co.uk/starter) and invited young people (n = 75) across three secondary schools in urban, rural and coastal areas of Wales to take part in a ‘creative RSE audit’ (see Renold and Timperley Citation2023) to find out what they want to learn, are already learning, and how in the broad area of RSE. Activities included image elicitation (see Renold and Timperley Citation2023), writing on stones what might be too heavy to learn about, putting messages in glass jars about what mattered most to them and pegging up stop/start activist plates (see the methods in action in our film, ‘UnboXing RSE’ (https://vimeo.com/user29658411)). In the second phase, we worked with a fourth school, located in a semi-rural ex-mining post-industrial Welsh valleys town. Here, we collaborated with Sior (pseudonym), an artist-in-residence teacher assistant, a film-maker (Heloise) and a composer (Rowan) all of whom have collaborated with EJ in previous coproduced projects, but were new to Vicky. In this phase, 18 young people took part in a two-hour creative RSE audit, and a diverse group of 11 young peopleFootnote5 (age 13–14) opted to continue to creatively unbox what mattered to them over 12 months, across approximately 10 further 2-hour sessions.Footnote6 They had access to a hard copy of the AGENDA resource and one of the sessions involved meeting dartaphacts from previous research and engagement projects created in the wider community. EJ has a long history of working with Heloise (film-maker), Rowan (composer) across multiple Agenda-making projects. This was the first project, however, to explicitly invite young people to direct Heloise and Rowan, guiding how their evolving dartaphacts might be reanimated with sound and movement through film, and with the potential for them to be shared with others (other young people, teachers, professionals, policy makers etc). Although the project stuttered and stalled as we all navigated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, we continued to work with the group across a further year as their dartaphacts made their way out into the world. This included conducting a series of ‘intra-viewsFootnote7’, post-project speculations prompted by reviewing their films. And while ‘what matters’ is still on the move, the creative dartaphacts,Footnote8 to date, include a series coproduced two-minute films, individual participant photobooks, one collective photobook of the process, a suite of password protected individual and group project Padlets and two longer 10-minute films that capture the unboXing process for practitioners.

Why unboXing?

The focus on ‘unboXing’ originally emerged as a practical idea to bring the creative audit materials into the research space. However, it soon morphed into a post-qualitative concept, and anchored the project in two ways. First, inviting young people to ‘unbox RSE’ connects to the YouTube unboxing phenomenon (see Mowlabocus Citation2020), especially the affective and haptic pleasure in the opening process in and of itself, rather than in the contents inside. This element resonated powerfully for us in terms of the project’s speculative praxis towards art-as-way as opposed to art-as-output and our aim for our living RSE curriculum ‘to remain open to the unpredictability and uncertainty of the encounter, in terms of what may emerge’ (Quinlivan Citation2018, 170). Second, we were invited to work creatively with how quantitative surveys mark, measure and make experience matter – surveys that too often exclude what can (e.g. gender identity categories) and cannot be ‘counted’ (e.g. embodied knowing). As postqualitative researchers we embraced the challenge, both in our project title, with the capitalized X discursively signalling a ‘portal to the unknown’ (see Bond-Stockton Citation2021Footnote9) and in the core message of our film, ‘UnboXing RSE with a creative audit’ which explicitly states how the messiness of lived experience will always exceed the boxes that society uses to render lived experience intelligible (Halberstam Citation2020).

From the outset, then, our use of the term ‘unboXing’ acknowledges the ‘radical openness’ (Barad Citation2007) of the qualitative multiplicity of life and its infinity of possibilities, all of which lies at the heart of Barad’s concept of ‘mattering’. To register the ontological indeterminacy of what comes to matter in the making of dartaphacts, we draw upon Erin Manning’s (Citation2013) concept of the ‘more-than’ and Guattari’s (Citation2015) concept of ‘transversality’ (see Palmer and Panayotov Citation2016-07). The more-than gestures towards the ongoing variation of experience, where experience is always already inventive and carries traces of the past that propels a feeling-forth of becoming Otherwise. Attending to the transversality of experiential matters also keeps Barad’s time–space-mattering in check by being open to how experience crisscrosses multiple territories (biological, ethological, socio-cultural, machinic, digital, cosmic etc.). We also add an asterisk to the concept of ‘trans*versal’. Usually deployed in surveys to mark the outliers, anomalies and exceptions, our asterisk operates instead as a political wild card (Halberstam and Nyong’o Citation2018, Van der Tuin and Verhoeff Citation2022, 31). It gestures towards the rhizomatic relationality and connectivity of all things. We turn now to the milieu of the art classroom and the importance of making room for the ‘more than’ of what matters to surface.

Making con-sense-ual matter in the cwtch of an art classroom

Art classrooms often occupy affirmative liminal spaces in secondary schools with pedagogic rhythms, structures, values and affective atmospheres that can be more participatory and inclusive (see Thomson and Hall Citation2021). The ecology – that is, the ‘relational-qualitative goings on’ (Massumi Citation2011, 20) – of Sior’s art classroom, was no exception. As a regular visitor for close to 10 years, EJ (and the artists they work with) had become attuned to how Sior’s classroom often operates as a cwtch (the Welsh word for safe place, hide-away, cuddle) for many children and young people, especially for those who struggle with the weight of living life on the edge, or as social/cultural/embodied outsiders to presumed normative ways of being. As an artist in residence, Sior also occupies a liminal position in the school, his outsider status, perhaps intensifying what might be possible for young people to make in this space. Like many art classrooms, finished and unfinished artworks, buzzing with past pheels (ie. posthuman affects) populate the walls and hang from the ceiling. In contrast to many teachers in this school, Sior is also from the community and his practice as an artist in residence has become more and more attuned to how his classroom has become a sanctuary that enables young people to not only ‘stay with the trouble’ (Haraway Citation2016) but to ‘make with the trouble’. It is commonplace for students to use the space at lunchtime, and during breaks or free periods to eat, sit, talk, be silent, be noisy, draw, paint, sculpt – on their own or with friends. However, since COVID-19, and during the UnboXing RSE project, this space has become increasingly populated and intensively chaotic. Consensual practices (e.g. lingering at the door to be invited in) have evaporated and authoritarian and regulatory pedagogies were sliding into the space to tame the chaos. We had to work hard to re-create the affective atmosphere that the arts classroom-as-cwtch used to generate.

Making consent matter with creative methods has become a central part of our pARTicipatory approach to posthuman ethics (Renold and Edwards Citation2018). During the first session we invited young people, on their own or in their friendship groups, to write down on coloured paper clouds how they might make the art classroom a safe, inclusive and supportive space to create artefacts on potentially sensitive issues together. Each cloud was threaded with a piece of string and hung on a coat hanger to create a support cloud mobile. Exploring how safety and support look and feel before a research and engagement project begins is an activity adapted from the AGENDA resource.Footnote10 Here we shift away from the notion of safety solely within the context of educational safeguarding discourses, to draw on the Latin roots of ‘safe’ as in ‘whole’ and ‘connecting to others’ (Renold Citation2019). We emphasize how safety and support are relational and mobile endeavours – materialized when individual clouds become a collective cloud mobile.

Like most projects we have been involved in, aside from a general school code of behavioural conduct, the young people had no experience of being asked their views. They did not recall ever being invited to coproduce what might make a safe and supportive space for RSE-focused work. What surfaced called for a mixture of affirmative and prohibitive behaviours and feelings. We have crafted these messages in the form of an illustrated data-poem shaped as a question mark to signal its uncertainty:

A safe space

nice vibes

being aware

of our feelings

appreciate others

trust others

respect others

inclusive of all genders and sexualities

consent

privacy

protect

our anonymity

don’t put us on the spot

don’t ask us to speak in front of the class

ask our permission to be recorded

no accidental filming

Stengers (Citation2021, 85) writes that, ‘a sensible event (…) requires allowing oneself to be touched, and allowing what touches you the power to modify the way you relate’. Week after week, we became more attuned to the processual ethics of becoming creative with ‘art-as-way’ in the cwtch – a con-sense-ual praxis generated with young people and apARTicipatory affirmative praxis that materialized in many of the group’s post-project reflections. We share these expressions for readers to carry with them as we unbox what came to matter. We have formed them in the shape of an exclamation mark, to capture our perpetual surprise at how the cwtch seemed to enable a being-doing-knowing of becoming artful Otherwise.

‘I loved that you can

come and just be’.

‘One of the highlights

of the school week,

knowing that I got to

come here and just DO’

‘You could do stuff you

didn’t know you could do’

‘For me, it’s not just art,

it’s like a way … another

language and people can

understand that language

just by looking at it’

‘Sharing the voice of

people who can and

can’t be heard’

‘If you can’t say it

out loud, say it with art’

‘Creativity is everywhere’

‘Everything matters’

Making RSE dartaphacts

The art classroom very quickly became what Erin Manning writes about as a ‘relational contact zone’ where young people began making otherworldly dartaphacts by ‘improvising with the already-felts’ (Manning Citation2009, 30) on matters which might have started as a message in a jar, or on a paper plate, but soon became more-than. As Haraway (Citation2008, 219) has also noted, ‘contact zones change the subject – all the subjects – in surprising ways’ (see also Wilson Citation2019). What surfaced over the coming weeks was a rhizomatic web of multi-dividual discursive-material matterings – a collective living RSE curriculum uprooting and re-routing the often stale and stagnant words and concepts that populate the content of many school-based RSE curricula (e.g. gender, sexuality, rights, risk, violence, consent etc.). We structure these stARTing moments through a series of becomings to glimpse at the diverse ways each dartaphact-in-the-making was taking shape. We also include their titles and a hyperlink to the photobooks that share anonymous images of some of their making moments for readers who want more than this paper can offer.

Focused becomings

Some young people arrive with a strong sense of what they want to raise awareness of. Aiza (pseudonym) writes the words, ‘human rights’, ‘world rights’ and ‘relationship rights’ on almost every stARter activity. In the first session, she seeks permission to make ‘something political’ – something she feels ‘angry’ about. Perhaps touched by the images we shared in the ‘Life Support’ film of young people flying super-sized silk body outlines on sticks at the top of their local mountain, Aiza makes a large silk flag. After a practice attempt on a small square of silk (which later became a superhero cape for her teddy), she carefully fills the silk with Palestinian colours and calls her dartaphact ‘Freedom?’ (https://vimeo.com/949570814).

One group’s dartaphact ideas seem to be sparked by the stARTer activities. They have a ‘plan’ as ‘big Marvel fans’ to re-create their version of the ‘powerful’ Scarlet Witch (aka WandaVision) and her ability to warp and dictate reality by summoning the forces of chaos magic through a subtle wiggle of her two middle fingers. They invite all of us to add to their pile of red ‘stop’ plates. The plates are eventually pinned to a protective red foam tabard and fashioned as body armour to soak up and deflect the ‘bullies’ of the world. Over the weeks they make an eye mask and a red wool pom-pom which is attached to their wrists to produce the power of the ‘Red Wiggly Woo’ (https://vimeo.com/949907509) – the title of their dartaphact ().

Rose (pseudonym) arrives a week late into the project. She also re-materializes an adapted stARTer activity. Having run out of glass jars, we bring a large clear bauble for Rose to collect ‘what jars’ her. The bauble becomes the base for a paper mâché and clay head. Rose randomly selects the messages she and her friends have inserted into the bauble around the theme of body image and re-writes them on shards of mirror. The shards are inserted into the head which is then painted half black and half white. Contrasting facial expressions are sculpted into each half. Over the weeks it is grafted onto a discarded paper mâché body from a previous school project. Rose’s piece holds onto the unknown and calls her dartaphact ‘untitled’ (https://vimeo.com/949909258).

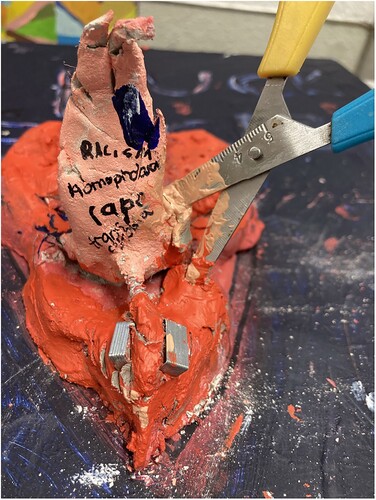

Discarded becomings

For Alys (pseudonym), early plans and ideas are discarded once the speculative quality of making creative activisms is embraced. Changing tack from making a ‘cute little LGBTQ rainbow heart’ Alys creates the dartaphact, the Bruised Heart (https://vimeo.com/949903580, ). Unbeknown to us at the time, she worked with the messages in her jar about the rage she felt in being attacked for making trouble as a pre-teen digital feminist activist and for speaking openly about her sexual identity in primary school. These messages are rolled up and inserted into the heart. A long, curved clay tongue protrudes from the heart, inspired by the ‘Attack on TitanFootnote11’ Japanese manga series. The tongue is slashed (with scissors) and screwed (with small metal screws) to capture, ‘the silence and torture of how society won’t listen’. Under the tongue, the words: ‘rape, racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia’, are written.

Overwhelming becomings

Elle (pseudonym) describes feeling overwhelmed by the inequalities and injustices that ‘are everywhere’ and how ‘everything matters’. An impromptu moment to start with the matter on the table takes flight as EJ and Elle look over at the Quality Street chocolate tin stuffed with empty wrappers (from earlier sessions). Elle’s dartaphact ‘eQuality vibrations’ materializes (https://vimeo.com/949906203). Post-its, populated with messages highlighting intersectional inequalities framed as affirmative statements, such as ‘disability rights’ and ‘we are not the same, but equal’ are pasted onto the tin and layered with the colourful translucent sweet wrappers. Over the weeks, Elle finds a ‘way’ to become creative as she scores stitched scars on an old mannequin head, decorates the resulting patchwork with bright colours, and inserts folded paper messages, ‘you can never know’ into a spinning hat-like carousel. Elle is partially deaf and wears hearing aids. ‘Feeling the words’ and watching them vibrate as they spin was a vital mattering and an idea that came through in the making. We pick up the notion of feeling sound in the next section.

Inclusive becomings

Some dartaphacts breach the threshold of the art classroom and invite others to participate in making what matters. During the first session, Kae (pseudonym) dives into their bag and pulls out a copy of Dean Atta’s (Citation2019) book ‘The Black Flamingo’. It is a story that poetically charts the life of a young black gay teen who finds his voice and wings as a drag artist at university. The book quivers with creative potential and over the coming weeks, the dartaphact ‘Underneath the black feathers’ materializes (https://vimeo.com/949908563). Kae works with their friend, Max (pseudonym), and they focus on creating a platform for LGBTQ+ youth voice – a powerful moment, we later learn, in a school yet to form an LGBTQ+ group for its growing LGBTQ+ population. Inspired by the book, they ask for black and multi-coloured feathers, masks, paint, gold drawing pins and glitter. Kae’s mask is painted black and sports a multi-coloured feathered mohawk, graffitied with their favourite phrases from the book: ‘Flamingos fighting look just like kissing’, ‘Some men have vaginas’, ‘Barbies and Belongings’, ‘I want to be fierce’, ‘Drag’, ‘I don’t feel queer enough’ and ‘The Black Flamingo’. Max’s mask is painted deep pink with blackened eyes and sprouts horns made from sparkly pipe-cleaners. Max also designs a third mask. The outside is covered with LGBTQ+ symbols. Pejorative and oppressive statements populate the inside. As the masks take shape, a clay pillow is also in the making. They paint it bright red, pierce it with gold drawing pins and glue it with a top border of black and multi-coloured feathers. When EJ asks about the pins, Kae explains how they came to matter in the making process:

The pins coming through is about trying to hold yourself together … so there are lots of them … if you touch them … you can feel every single pin … it hurts … that’s what it feels like when you get told these things.

Rhizomatic becomings

‘Well … I like drawing mushrooms?’. This statement was one young person’s starting gesture when they were asked what they might create. It is a moment that literally mushrooms into one of the project’s anchoring pieces, a dartaphact eventually titled ‘Majestic Insecurity’ made from clay and plaster of Paris (https://vimeo.com/949906891). Everyone pARTicipates in making this ever-expanding fruiting body. No one seems to question the ‘why’ of the mushroom (e.g. what did it mean?). We all become progressively intrigued as the mushroom cap sprouts multiple eyes, and a tiny little brown gate skirts the base, later populated with worms and snails. While the queer ecology of fungi is not lost on us (see Marston Citation2025b), it is the affective and rhizomatic quality of making the mushroom that surfaces. Colouring in its multiple eyes, two of its makers start talking about how

it’s in a virtual reality and it’s in the actual world … just eyes, no mouth … because it can’t talk to anyone about problems … too shy to say … and every time it blinks … the more emotional it gets, so we added a fence, to keep it calm … but its trapped, coz it’s growing oversized.

Animating dartaphacts for the more-than of ‘what matters’

While the verb animate is commonly used to refer to moving pictures and cartoons (since the 1880s), in this section, we engage the more capacious 1530s definition (https://www.etymonline.com/word/animate) ‘to give breath to’ (ane), ‘to endow with spirit’ (anima), ‘fill with boldness or courage’ (animare). This process of animating the dartaphacts seemed to embolden and enliven ‘what matters’ – a polyvocal, audio-visual and affective mattering that brought the more-than of the dartaphacts to life. We focus first on sharing some of the ways the young people engaged Rowan and Heloise to co-compose their films, we then zoom in on the animation of one of the dartaphacts, the Bruised Heart.

Making Sonic Sho(o)ts

Some young people, like the young people who made the Red Wiggly Woo, had firm ideas on how to reanimate their dartaphact from the outset: a WandaVision-inspired ‘theme-tune', a green screen to anonymise each other, bring movement to the gloves and ‘chaos magic’ of the wiggly woos, and through which they could project their rocky mountain landscape (https://vimeo.com/829053226). For most, however, it was not until they completed their pieces that they explored how their dartaphacts might be enlivened through sound, and then movement. Some young people invited our artists to respond in ways that captured how their dartaphacts affected them in the making process. For example, Aiza directed Rowan to create the ‘sounds of the chant, Free Palestine’ and ‘sounds of flags flowing in the air’. She also gave Heloise a free rein on how to work with the flag footage. The only steer was for fluidity and movement in the flag (see https://vimeo.com/829053226). Meanwhile, Kae and Max had a simple direction for Heloise to make their ‘feathers sway’ and create close-up shots of the pinned pillow and masks. Kae was the only young person to use their voice for the soundtrack. Acutely sensitive to the tone and pitch of their voice, the words from their mask are whispered. Kae then invites Rowan to create a soundscape that intersperses the whispers, with flamingos flapping their wings (see https://vimeo.com/829054199).

Feeling heard, for Ella, was strongly felt (see https://vimeo.com/829046762). Her piece took the sense of sound into the title (‘eQuality vibrations’) with an instruction that the soundscape ‘gets you to feel the different textures and vibrations of the messages … all the thoughts you cannot know going around and around’. While the soundscape focused Elle’s attention, it was movement that brought Rose’s sharded yin-yang head to life. Inspired by Einstein’s famous 1930s quote, ‘Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving’, Rose asks Heloise if she can make her head travel through forests on a bike (see https://vimeo.com/829055185). It was only later, in our post-project reflection (where we used the short films as audio-visual prompts) that Rose talked about how she takes ‘risky jumps … through forests and water’ on her bike. She described biking as an ‘emotional ride’ – how it makes her ‘feel connected … you can calm down … you are with the wilds … you can get away from reality’. As we explore further below, for some young people, animating their dartaphacts allowed us to glimpse at the unanticipated ways the process seemed to open up ‘what matters’ to their trans*versal more-than, both in their making and viewing.

An assemblage ignites

Alys’s dartaphact, the ‘Bruised Heart’, seemed to embrace the dual refrain that many of the dartaphacts expressed – ‘capturing the silence and torture of how society won’t listen’. Dripping with political yield, it viscerally directs us to simultaneously ‘do something’ yet explicitly reaches out to what more this might be in its clarion call to ‘Fuck Society’. Struggling to exercise her voice (while a prolific insta-poet), Alys selects an instapoem about an invitation to a land of whispering woods from an unknown source on her Instagram feed. She invites Heloise to ‘be inspired by the quote’ and for Rowan, to overlay muffled voices with young children’s cries that get louder and louder amidst the sound of a beating heart.

What materializes is a film that Heloise later discloses was one of the most difficult and affectively charged films she has ever produced (see https://vimeo.com/828991152 ). The film also powerfully resonates with Alys, during our post-project intra-view: ‘it’s like she (Heloise) crawled into my mind’. The film opens, like all the films do, with unboXing a fragment of matter that will feature in the film. For the bruised heart, multiple images of a speaking heart, organ and tongue spill out (). One side of the box hosts the title of the piece – letters formed by fragments of the scissors that were used to slash the tongue. The opening frame brings the sound of a beating heart into play, and the heart with a slashed tongue slowly comes into focus. Heloise materializes the poem’s words, ‘In the darkest nights, come with me to the edge of the whispering words’. A small heart, glowing red, lurks at the back of a dark forest, accompanied by a baby’s cry and indecipherable chatter. In the next line, ‘across the bridge and over the still river’, a split screen visualizes the stilled heart and forest in one half and its mirror image in the second half. Here, the heart and tongue are moving with the ripples of a river, and the volume of the beating heart, cries, and chatter increases. The final line, ‘you’ll find me there waiting’, screens multiple slashed-tongued hearts pierced on the thorned branches of the forest trees (). The film then cuts to close-ups of the dartaphact, the screwed and slashed tongue protruding from a red heart with the perpetrating scissors stuck inside, and the headline, ‘Fuck Society’ and the words ‘transphobia, racism, homophobia, rape’ in full view. The film draws to a close with an audio-visual crescendo in which the clay grey heart, still beating but seizure-like, drained of colour, hovers hauntingly in the middle of an apocalyptic scene where forest trees are blazoned with embers and rooted in a bloody bed of red. The final frame cuts to a forged heart, now enflamed, and slowly burning to the sounds of post-industrial hammering (). The heartbeat fades away, and viewers are returned to the forest and forest sounds, but with a chink of light lurking in the distance.

There is always a trembling uncertainty when a film is gifted back and shared. In the making of the Bruised Heart, the connection was immediate and gut-felt. During our one-to-one post-project intra-view, the more-than of the film ignited a wider assemblage in a rare moment of deep entanglement that few projects surface, although the prehensions are often felt.

We find out, after the film had been made, that Alys has a strong relationship with feminist and queer poetry known on social media as insta-poetry, especially the poets Rupi Kaur, Atticas, and Amanda Lovelace. She started writing her own insta-poetry in Year 7 (aged 11) and even shares some in the intra-view, an uncanny moment where the poem she selects depicts thorns and withered, pierced hearts (a poem written months before the film was made). She reflects on the heart bursting into flames at the film’s end and talks about how suppressed emotions can explode like fire: ‘It’s like you’ve been through so much and then you’re just – you explode … and then – like it’s on fire’. However, the exploding heart at the end of the film connects to a wider assemblage – a tran*sversal connection to the activist legacy of Alys’ mining ancestors and the silencing of speaking out.

The images in this film are reminiscent of the flames, seismic ruptures, molten gold, and hammering relating to the industrial landscape that this town and the valleys more widely were at the epicentre (see Ivinson and Renold Citation2022). EJ mentions this connection to the post-industrial past and heritage. Expecting this inquiry to fall a little flat, given their conversation about feminist activist instapoetry and thwarted and troubled romance, Alys swiftly interjects and tells EJ that her great-great-granddad had pulled children from the slagheap that had engulfed a primary school during the Aberfan disaster of 1966 killing 144 people, 116 were children (Nield Citation2014). The local miners had been telling the mine owners for a long time that the land was unstable and repeatedly warned of a disaster waiting to happen but were not listened to. We speculate that Aberfan was evoked by the trans*versal aesthetics of the film, connecting a present experience of not being heard on matters of societal gender, sexual and racist abuse with a history of local knowledge that had persistently been silenced. Months later, long after the project launch, Alys tells EJ that she often writes her instapoems down by the river, ‘turning what’s painful into something beautiful’ – the same river where she has also learned, over time, to mine for crystals – resource-ful posthuman companions, which she keeps in her bedroom and under her pillow, for protection, for peace, for power.

Over the years we have become more and more attuned to how ‘what matters’ with young people can surface in multi-sensory arts-informed projects as ways of surviving, staying and making with the trouble – troubles that are always more than theirs. The final section of this paper maps moments in the journey of how dartaphacts as aesthetic, proto-political posthuman pARTicipants take flight, beyond the cwtch of the art classroom.

Dartaphacts take flight

Responding to the insistence of the cry, ‘It matters!’ does not mean justifying its claim, constructing the reasons why indeed it should matter (…) it involves intensifying it (…) giving it the power to problematize (…) and making things matter. (Stengers Citation2021, 86)

Professional Cwrdds

When budgets and projects allow, we can plan lightly for cwrdds that can field the potential of what a dartaphact can do. This Wellcome-funded project had a healthy budget and an engagement remit that enabled us to build upon previous events and co-produce and curate a cwrdd with what Massumi (Citation2019), citing Lozano-Hemmer calls a ‘relational architecture’ (see also de Freitas, Rousell, and Jäger Citation2020): that is, an event intentionally crafted to unsettle and offer the more-than of dissemination with a process that continues to expand and create. With little space to get to the fullness of the making and mattering of the entire event, we focus this section on two moments that capture this ‘more-than’ of ‘dissemination’.

We returned to a venue, the Pierhead in Cardiff Bay, that carried the affective residues of previous AGENDA cwrdds (see Renold, Edwards, and Huuki Citation2020). This venue has been a vital platform for installing RSE-infused dartaphacts over the years. It is a venue known for its multicultural heritage and platforming of political voice and agency: ‘to inspire a new generation to forge a Wales for the future’ (www.assembly.wales). Significantly, it is also a venue that must be sponsored by a member of the Welsh Government (i.e. by an elected Senedd member). Securing this venue for the ‘safe’ passage and performative potential of the dartaphacts and their makers was crucial, given the volatile climate in which RSE was (and continues to be) entangled.

While most of the young people wanted to be there, in person, they wanted their dartaphacts to ‘do the talking’. So we set about designing a space that might enable teachers, policy-makers, health practitioners, and other adult allies to be touched by and intra-act with their dartaphacts. The dartaphacts were installed on tables and raised on plinths around the room. We repurposed and reprinted the photo books originally created as a gift to the young people participating in the project. They were placed alongside each dartaphact. Sior suggested that the young people might like to write some text to accompany the title and image of each piece. This idea was re-routed when Elle picked up the image of the woods (from the Bruised HeART dartaphact) and stated that she liked the idea that there is just a title and image to draw people in: ‘It’s like the woods … people have to find their own path through what it might mean to them’. The woods became the backdrop for all the pieces and we recycled the jars to collect how some of those meanings might materialize (see ).

One week before the event, Queen Elizabeth II died. All government-sponsored events were cancelled, including ours.Footnote12 The next available slot to host our conference was four months later. While this break resulted in the loss of the Education Minister as keynote speaker, it materialized an agential cut that sparked Sior into action. He invited the original group, and other students (who, over time, became interested in what we were doing and what was coming to matter) to decorate a suite of jars designed to collect conference participants’ reflections on intra-acting with the dartaphacts. Bespoke mushrooms were attached to each jar lid as a gesture to our rhizomatic praxis, and embellished in ways that the dartaphact they were accompanying resonated with young people.

Installed safely inside the Pierhead, the dartaphacts vibrated as the eventful political enunciators we anticipated they had the potential to become. A relational architecture had been created. Old and new connections across political parties, groups, and organisations were forged. Young people and their dartaphacts intra-acted throughout the evening – making what matters seen, felt and heard. Jars were filled by conference participants with powerful messages about how the dartaphacts had impacted them. Cloud trees catching the discursive affects of watching the films were populated. Invitations to continue a paused RSE professional learning programme returned. Potential case studies to inform future government and non-governmental guidance were invited, and an embedded and embodied praxis put on hold during lockdown was enlivened once more and began to mushroom. While impossible to ‘evidence’ (as one participant wrote, ‘so wonderful … I’m lost for words’) it felt like we had cultivated a space that might just enable people to register the sticky, circulating affects (Ahmed Citation2005) in the here and now of ‘what matters’ in ways ‘that cannot be explained away’ (Stengers Citation2021, 86) and trust in this shaky, new RSE to come.

Home Cwrdds

Sometimes, dartaphacts enter or create a scene where what matters is already in germ. In this project, the creation and significance of ‘Freedom?’ seemed to embody just that. As soon as Aiza completes her silk flag, it is mounted on wood, and she takes it home. It never returns to the art classroom. During the co-production of the project launch, Aiza shares with us how and why this dartaphact is staying in place and how the politics of place and home matter. She tells us that her family are so proud of what she has made that the flag takes centre stage in their prayer room. Word spreads, and over the year, ‘Freedom?’ receives multiple visitors, including a refugee who ‘broke down and cried as soon as he saw it’. Aiza explains that ‘he thought that everyone had forgotten’ about the conflict. Busy unboXing human rights at home and for home, the dartaphact ‘Freedom?’ does not make a physical appearance at the project launch. It is rooted in place, matter-realizing a living curriculum (already in germ), raising awareness of human rights. How can it be uprooted when, as Aiza declares, ‘people from the Mosque keep coming along to see it?’. And so ‘Freedom?’ stays at home, its extra-beingness igniting multiple cwrdds – gatherings that, we speculate, may have intensified since writing this paper (https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/10/1142952). Indeed, the uncertainty captured by the question mark in ‘Freedom?’s title is painfully palpable.

Youth Cwrdds

We bring this section to a close with a focus on the making of a youth cwrdd and what a longitudinal legacy of a post-qualitative artful praxis that continues to inform what more a dartaphact can do.

In June 2018, over 200 young people (age 14–18) gathered at Cardiff City Hall to take part in a series of workshops that aimed to explore gender inequality with an intersectional lens. Young people came from LGBTQ+ groups, young asylum seekers groups, young carers groups, schools, and youth groups. EJ’s keynote speech at the start of the day shared the making of the ruler-skirt. At around this time, the Welsh Assembly Government was in the process of conducting a ‘rapid gender equality audit’. And so, an opportunity presented itself to canvas the views of those attending the assembly on what they felt needed to be changed to make Wales a more gender-equitable place. Marker pens and rulers were distributed, and ten minutes later over 180 rulers were inscribed with their messages. The rulers became ruler-skirts and have agitated policy and practice multiple times. They have also been worn by other young people shaking up what matters on a range of gender and sexual equalities issues (see Renold and Timperley Citation2021).

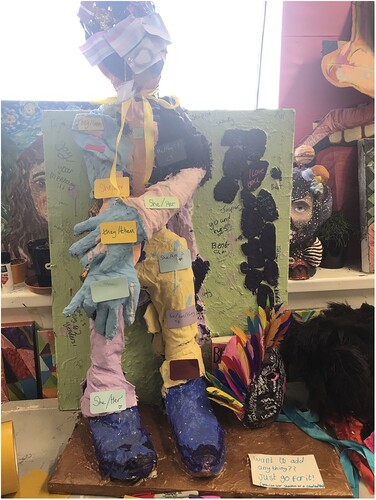

Five years later, EJ is invited back to run the same activity for the UNICEF-sponsored, Girls-Fest cwrdd with over 200 attendees, at Cardiff City Stadium. There is also an opportunity to run an additional creative workshop for young people throughout the day. EJ seizes the opportunity to distil and expand the activist praxis that formed the Red Wiggly Woo dartaphact. The organizer sources three large mannequins, a selection of red, green, and gold plates, and matching coloured capes. A new dartaphact in-the-making rises up and takes centre stage in the workshop space (). When young people inquire about what this activity might be, EJ shares the story of the Red Wiggly Woo, using the photo-book as a visual prompt. As the activist plates are pinned to the capes, and the embodiment of youth voice takes off, EJ no longer needs to invite or explain how to participate. The dartaphacts do the work, and another living curriculum is moving what matters. How these new dartaphacts might intensify the power to problematize what has surfaced is yet unknown, but their potential is felt.

While funded projects come to an end, the more-than of these trans*versal dartaphacts live on. The project’s protracted timeline has enabled several further unplanned cwrdds to make their way into the world. The rhizomatic mushrooming of how dartaphacts are mattering continues to proliferate in local and national policy, practice and activist assemblages. From the films to fragments of arts-based data, ‘what matters’ has been folded into and enlivened our online RSE professional learning programme, where we have been unboXing the matterphorical concepts of gender, sexuality and relationships to embrace a more expansive ecology of experience. Physical dartaphacts have been shared in higher education classrooms and at activist and remembrance events. Some have been adapted by young people in this project so they can travel on planes and trains to reach international audiences.Footnote13 With each outing, we collect what matters and share back, where possible, with its makers. These dartaphacts will no doubt continue to become use-full as new opportunities arise, and we will endeavour to embrace and entangle with the multiple ways of becoming response-able in ‘making things matter’ for an RSE yet to come.

Open endings …

If art is ‘to make felt an effect’ (Massumi Citation2013, 37) and open up proto-political spaces for ‘new collective assemblages of enunciation’ to emerge and form ‘out of fragmentary ventures’ (Guattari Citation1992/2006, 120) then the UnboXing RSE project was one such ad/venture and joins a lively collection of arts-informed projects and practices pushing the boundaries of what more relationships and sexuality education research can become (see Allen Citation2021; Gannon et al. Citation2025; Gilbert and Fields Citation2023; Renold et al. Citation2025). Our site of adventure and field of potential in this paper is the new statutory relationships and sexuality education curriculum in Wales, where ‘what matters’ must not be assumed in advance but co-constructed with children and young people. It is a paper that draws on and develops a phEmaterialist arts-activist praxis cultivated and sustained across years of learning how to ‘stay’ and make ‘with the trouble’ (Haraway 2016) in a terrain that has become increasingly riddled with risk, panic, protests and an enduring inability to register the complexity and capaciousness of what matters to children and young people.

The pARTicipatory project that we have shared fragments of in this paper explicitly set out to unbox the transdisciplinary potential of RSE. With ‘art-as-way’ we worked together to create an affirmative, care-full (de La Bellacasa Citation2017) and response-able praxis. . While planned future publications will open up the making and mattering of each dartaphact in all their spectacular and speculative promise (see Renold et al. Citation2024b; Renold Citation2025), we hope this paper has enabled readers to glimpse at resonant key moments for us on this never-ending post-qualitative journey: from how we have worked together to co-curate a con-sense-ual space for making with gender, sexuality and relationship troubles, to the diverse ways the dartaphacts have taken form – each carrying the discursive-material-affective spores of what more they might become when enlivened with sound, movement and words. Indeed, we continue to be stunned by the rhizomatic matterings that surfaced within and beyond that classroom. Becoming art-ful with RSE in this way, in an art classroom, and with artists and art teachers whom we have been collaborating with for many years, seemed to enable multiple experiences and expressions to rise and relate with affective intensities that we are only just beginning to make multiple sense of and with. We speculate, that in conducive ethical-political environments (our cwtches and cwrdds), the affective power of dartaphacts can cultivate new roots and routes:roots to unbox many of the stagnant concepts and codes that constrain ‘what matters’ and routes to connect to the capacious RSE that runs through, and is all around, us ‘composing with a reality that overflows ongoing attempts to classify and name’ (Stengers Citation2021, 88). This could be what making the more-than of ‘what matters’ pheels like; a living RSE curriculum in all its Majestic Insecurity, Untitled, Freedoms, Feathers, Bruised Hearts, Consent-quakes, eQuality Vibrations and Wiggly Woos.

Acknowledgements

A huge thank you to all the young people, their dartaphacts, the art teachers and artists, and the school for pARTicipating in the unboXing project and for becoming artful with how school-based RSE research might continue to matter. We would also like to thank and acknowledge the unwavering support of the wider Engaging Sexual Stories team (see https://www.natsal.ac.uk/related-projects/collaborations/engaging-sexual-stories/).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

EJ. Renold

EJ. Renold is Professor of Childhood Studies, at the School of Social Sciences, Cardiff University. Mixing the pragmatic with the speculative, EJ's feminist, posthuman and new materialist praxis (aka 'phEmaterialism') experiments with coproductive, creative and affective methodologies to ethically attune to, animate and ampllify how gender and sexuality come to matter in children and young people's everyday lives (www.productivemargins.ac.uk). EJ also creates relationships and sexuality (RSE) education resources with and for young people and practitioners (www.agendaonline.co.uk) and has been a regular government advisor for Wales' Relationships and Sexuality Education curriculum.

Victoria Timperley

Victoria Timperley is an education Lecturer in the School of Social Sciences at Cardiff University. Her research uses qualitative and creative methods to focus on young people, gender and sexuality, and digital health and well–being. Her doctoral research focused on these issues with young people who have additional learning rights.

Notes

1 ‘PhEmaterialism’ (Feminist Posthuman and New Materialisms in Education) started out as the Twitter hashtag in 2015 for the network conference, Feminist Posthuman New Materialism: Research Methodologies in Education: ‘Capturing Affect’ (Ringrose et al. Citation2019). However, it rapidly became a concept-making-event and website (phematerialism.org) bringing together a globally dispersed collective of students, researchers, and artists experimenting with how posthuman and new materialism theories form, in-form and reassemble educational research.

2 We shift ‘intervention’ to the Baradian inflected ‘intra-vention’ to better capture our ongoing and entangled engagement with this live/ly RSE policy and practice assemblage.

3 As Kathleen Stewart (Citation2014) writes, an ‘empirical attunement’ is leaning into a moment that is ‘opening up’ the process of making things matter.

4 We capitalise ART in pARTicipatory to emphasis the process of art-as-way in our participatory praxis.

5 Our coproduced praxis for this project is not to categorise young people in terms of the usual socio-cultural markers of difference and diversity (e.g. gender, sexuality, ethnicity, social class, ethnicity, disability, neurodiversity etc.). Rather, difference and diversity surface in the descriptions of the making and mattering of young people’s dartaphacts.

6 The sessions were mostly conducted during lunchtimes and permission was sought to miss either the final lesson of the day and/or the lesson before lunch.

7 We use the term ‘intra-view’ rather than ‘interview’ to acknowledge our relational entanglement in the making process, and our speculative aim to generate new ‘matters’ (e.g. questions, ideas, feelings) in re-viewing the films with young people on the process of becoming a participant in the project.

8 This project is a Wellcome Trust funded public engagement research project (Reference UNS100842) and conducted in collaboration with The Open University, UCL London, Cardiff University, and the UK sexual health charity Brook. See https://www.natsal.ac.uk/related-projects/collaborations/engaging-sexual-stories/ for further details. The project received ethical approval from Cardiff University. While each young person and their parent/carer gave their consent before taking part in the research, the process of informed consent was on-going throughout the fieldwork sessions (see Renold et al. Citation2008). In practice this meant, for example, checking in with young people each time we took photographs or anonymised film clips of them making their dartaphacts, and checking in with young people throughout the project to ensure that they still consented for their words and images to become research data and drawn upon anonymously in reports, films, future publications etc.

9 See Bond-Stockton’s (Citation2021, 29–30) summary of how ‘portal and erasure meet in the X’ : from the X in Latinx that registers the refusal of gender binaries in Latin and indigenous populations, to the origin of the Mathematical X and how it is used to represent an unknown quantity or variable.

10 Making a ‘support cloud mobile’ was first piloted in the making of the co-produced resource AGENDA: A Young People’s Guide to Making Positive Relationships Matter, and then became a core safeguarding section in the resource (see Renold Citation2019, 230, www.agendaonline.co.uk/keeping_safe).

11 This is a series that is set in a world where humanity is forced to live in cities surrounded by walls that protect inhabitants from huge man-eating humanoids referred to as Titans. In this series, humanity is the monstrous other and the Titans have posthuman strength where body parts can harden and become impenetrable.

12 See this project blog for how the UnboXing project was integrated within the wider project launch: https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/news/view/2694859-supporting-the-new-relationships-and-sexuality-education-rse-curriculum.

13 Kae created a miniature version of their dartaphact (‘mini-bob’) so that it could travel to London based conference, “Living Gender in Diverse Times” Sharing their film, Underneath the Black Feathers’ within the wider context of RSE changes in Wales, stilled a packed audience (n = 40+) and moved two parents to tears. Their tears, they said, were tears of hope as they learned about the potential of what a creative curriculum could do when it was embedded in LGBTQ+ inclusive statutory guidance.

References

- Ahmed, S. 2005. "The Skin of the Community: Affect and Boundary Formation." In Revolt, Affect, Collectivity: The Unstable Boundaries Of Kristeva's Polis, edited by T. Chanter and E. P. Ziarek, 95–111. State University of New York Press.

- Allen, L. 2020. "Sexuality Education and Feminist New Materialisms." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality in Education, edited by C. Mayo. Oxford University Press.

- Allen, L. 2021. Breathing Life into Sexuality Education. New York: PalgraveMacmillan.

- Ashton, M. R. 2023. “ReAssembling Welsh Relationships and Sexuality Education: A Post-Qualitative Journey Through Dynamic Policy-Practice Contexts.” Unpublished doctoral diss. Cardiff: Cardiff University.

- Atta, D. 2019. The Black Flamingo. London: Hodder.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Barad, K. 2012. “Interview with Karen Barad.” In New Materialism: Interviews and Cartographies, edited by R. Dolphijn and I. van der Tuin, 48–71. Michigan: Open Humanities Press.

- Blaikie, F., ed. 2021. Visual and Cultural Identity Constructs of Global Youth and Young Adults: Situated, Embodied and Performed Ways of Being, Engaging and Belonging. London/New York: Routledge.

- Bond-Stockton, K. 2021. Gender(s). Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Braidotti, R. 2010. “The New Activism: A Plea for Affirmative Ethics.” In Art and Activism in the Age of Globalization, edited by L. De Cauter, 264–272. NAi Publishers.

- Butler, J. 2024. Who’s Afraid of Gender? London: Allen Lane/Penguin Presss.

- Chen, M. Y. 2019. “Agitation.” South Atlantic Quarterly 117 (3): 551–566. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-6942147.

- Coleman, R., T. Page, and H. Palmer. 2019. “Introduction. Feminist New Materialist Practice: The Mattering of Methods.” MAI: Feminism & Visual Culture 4: 1–10.

- de Freitas, Elizabeth, David Rousell, and Nils Jäger. 2020. “Relational Architectures and Wearable Space: Smart Schools and the Politics of Ubiquitous Sensation.” Research in Education 107 (1): 10–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034523719883667.

- de La Bellacasa, M. P. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds, Vol. 41. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

- Donaldson, G. 2016. “A Systematic Approach to Curriculum Reform in Wales.” Wales Journal of Education 18 (1): 7–20.

- Gandorfer, D., and Z. Ayub. 2021. “Introduction: Matterphorical.” Theory & Event 24 (1): 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1353/tae.2021.0001.

- Gannon, S., A. Pasley, and J. Osgood, eds. 2025. Gender Un/Bound: Traversing Educational Possibilities. London: Routledge.

- Gilbert, J., and J. Fields. 2023. “Adventures in Gender and Sexualities Education: Moments of Wonder.” Sex Education 23 (2): 148–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2023.2167160.

- Government, Welsh. 2020. Cross-Cutting Themes for Designing your Curriculum. Hwb.

- Guattari, F. 1992/2006. Chaosmosis: An Ethico-Aesthetic Paradigm. Sydney: Power Publications.

- Guattari, F. 2015. "Transdisciplinarity Must Become Transversality." Theory, Culture & Society 32 (5-6): 131–137.

- Halberstam, J. 2020. Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Halberstam, J., and T. Nyong’o. 2018. “Introduction: Theory in the Wild.” South Atlantic Quarterly 117 (3): 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-6942081.

- Haraway, D. 2008. When Species Meet. Durham, NC: University of Minnesota Press.

- Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Harris, D. 2021. Creative Agency. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hickey-Moody, A., C. Horn, M. Willcox, and E. Florence. 2021. Arts-Based Methods for Research with Children. New York City: Springer Nature.

- Ivinson, G. M., and E. J. Renold. 2022. “Emplaced Activism: What-If Environmental Education Attuned to Young People’s Entanglements with Post-Industrial Landscapes.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 38 (3-4): 415–430.

- Lenz Taguchi, H., and A. Palmer. 2013. “A Diffractive and Deleuzian Approach to Analysing Interview Data.” An International Interdisciplinary Journal 13: 265–281.

- Lupton, D., and D. Leahy, eds. 2021. Creative Approaches to Health Education: New Ways of Thinking, Making, Doing, Teaching and Learning. London: Routledge.

- Manning, E. 2009. Relationscapes: Movement, Art, Philosophy. Cambridge, MA. MIT Press.

- Manning, E. 2013. Always More Than One: Individuation’s Dance. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Manning, E. 2020. For a Pragmatics of the Useless. Durham/London: Duke University Press.

- Marks, L. U. 2024. The Fold: From Your Body to the Cosmos. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Marston, K. 2025a, in press. “The Future is Fungal? Imagining More Gender Expansive Futures.” In Gender Un/Bound: Traversing Educational Possibilities, edited by S. Gannon, A. Pasley, and J. Osgood. London: Routledge.

- Marston, K. 2025b, forthcoming. “Creatively Exploring Gender and Sexuality in the ‘Lower Plants’ Collection.” In Creative Research on Gender and Sexuality with Children and Young People: Making Methods Matter, edited by EJ. Renold, et al. London: Routledge.

- Massumi, B. 2011. Semblance and Event: Activist Philosophy and the Occurrent Arts. Cambridge, MA: MIT press.

- Massumi, B. 2013. Semblance and Event: Activist Philosophy and the Occurrent Arts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Massumi, B. 2017. The Principle of Unrest: Activist Philosophy in the Expanded Field, 148. London: Open Humanities Press.

- Massumi, B. 2019. Architectures of the Unforeseen: Essays in the Occurrent Arts. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mowlabocus, S. 2020. “‘Let’s Get This Thing Open’: The Pleasures of Unboxing Videos.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 23 (4): 564–579. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549418810098.

- Nield, T. 2014. Underlands: A Journey through Britain's Lost Landscapes. London, UK: Granta.

- Palmer, H., and S. Panayotov. 2016. Transversality. Accessed 9 July https://newmaterialism.eu/almanac/t/transversality.html

- Pihkala, S., and T. Huuki. 2019. “How a Hashtag Matters–Crafting Response (-Abilities) Through Research-Activism on Sexual Harassment in Pre-Teen Peer Cultures.” Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology 10 (2–3): 242–258. https://doi.org/10.7577/rerm.3678.

- Quinlivan, K. 2018. Exploring Contemporary Issues in Sexuality Education with Young People. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Renold, E. 2018. “‘Feel What I Feel”: Teen Girls, Sexual Violence and Exploring how our Research Practices Matter Through Arts-Based Methodologies.” Journal of Gender Studies 27 (1): 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2017.1296352.

- Renold, E. 2019. “Becoming AGENDA: The Making and Mattering of a Youth Activist Resource on Gender and Sexual Violence.” Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology 10 (2-3): 208–241. https://doi.org/10.7577/rerm.3677.

- Renold, EJ. 2024. “Becoming Creative in pARTicipatory Sexuality Education Research.” In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Sexuality Education, edited by L. Allen and M. L. Rasmussen, 1–12. London: Palgrave.

- Renold, EJ. 2025, In press. “Underneath the Black Feathers: Creatively UnboXing the More-Than of Gender Identity.” In Gender Un/Bound: Traversing Educational Possibilities, edited by S. Gannon, A. Pasley, and J. Osgood. London: Routledge.

- Renold, EJ., M. R. Ashton, and E. McGeeney. 2021. “What if?: Becoming Response-Able with the Making and Mattering of a New Relationships and Sexuality Education Curriculum.” Professional Development in Education 47 (2–3): 538–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1891956.

- Renold, EJ., S. Bragg, J. Ringrose, B. Milne, E. McGeeney, and V. Timperley. 2024a. Attune, Animate and Amplify: Creating Youth Voice Assemblages in pARTicipatory Sexuality Education Research. Children & Society. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12862.

- Renold, E., and V. Edwards. 2018. “Making ‘Informed Consent’ Matter: Crafting Ethical Objects in Participatory Research with Children.” Ethical Issues in Educational Research 136: 23–25.

- Renold, EJ., V. Edwards, and T. Huuki. 2020. “Becoming Eventful: Making the ‘More-Than’ of a Youth Activist Conference Matter.” Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 25 (3): 441–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2020.1767562.

- Renold, EJ., H. Godfrey-Talbot, and V. Timperley. 2024b. “Trans*Disciplinary Dartaphacts: UnboXing Relationships and Sexuality Education with the Visual Arts.” In Routledge International Handbook of Transdisciplinary Feminist Research and Methodological Praxis, edited by Jasmine Ulmer, Christina Hughes, Michelle Salazar Pérez, and Carol A. Taylor, 14. London.

- Renold, E., S. Holland, N. J. Ross, and A. Hillman. 2008. "Becoming Participant' Problematizing Informed Consent' in Participatory Research with Young People in Care." Qualitative Social Work 7 (4): 427–447.

- Renold, EJ., T. Huuki, S. Pihkala, and C. Taylor. 2025, forthcoming. Creative Research on Gender and Sexuality with Children and Young People: Making Methods Matter. London: Routledge.

- Renold, EJ., and G. Ivinson. 2022. “Posthuman Co-Production: Becoming Response-Able with What Matters.” Qualitative Research Journal 22 (1): 108–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-01-2021-0005.

- Renold, E., and E. Mcgeeney. 2017a. The Future of the Sex and Relationships Education Curriculum in Wales. Wales: Welsh Government.

- Renold, E., and E. Mcgeeney. 2017b. Informing the Future of the Sex and Relationships Education Curriculum in Wales. Cardiff: Cardiff University.

- Renold, E., and J. Ringrose. 2019. “JARing: Making Phematerialist Research Practices Matter.” MAI: Feminism and Visual Culture, Spring Issue 9. Accessed 9 July https://maifeminism.com/introducing-phematerialism-feminist-posthuman-and-new-materialistresearch-methodologies-in-education/

- Renold, EJ., and V. Timperley. 2023. “Once Upon a Crush Story: Transforming Relationships and Sexuality Education with a Post-Qualitative Art-ful Praxis.” Sex Education 23 (3): 304–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2022.2090915.

- Renold, EJ., and V. Timperley. 2021. "Re-Assembling the Rules: Becoming Creative with Making ‘Youth Voice’ Matter in the Field of Relationships and Sexuality Education." In Creative Approaches to Health Education, 87-104. London: Routledge.

- Ringrose, J., K. Regehr, and S. Zarabadi. 2021. “Feminist Craftivist Collaging: Re-Mattering the bad Affects of Advertising.” In Creative Approaches to Health Education, edited by D. Lupton and D. Leahy, 105–122. London: Routledge.

- Ringrose, J., K. Warfield, and S. Zarabadi, eds. 2019. Feminist Posthumanisms, New Materialisms and Education. London and New York: Routledge.

- Rosiek, T. 2017. “Making Connections Between New Materialism and Contemporary Pragmatism in Arts-Based Research.” In Arts-Based Research in Education Foundations for Practice, edited by M. Cahnmann-Taylor and R. Siegesmund, 32–47. Routledge.

- Setty, E., and E. Dobson. 2023. “Children and Society Policy Review-A Review of Government Consultation Processes When Engaging with Children and Young People about the Statutory Guidance for Relationships and Sex Education in schools in England.” Children and Society 37 (5): 1646–1657.

- Snaza, N., and A. Mishra Tarc. 2019. “‘To Wake Up our Minds’: The re-Enchantment of Praxis in Sylvia Wynter.” Curriculum Inquiry 49 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2018.1552418.

- Stanhope, C. 2022. “PhEminist Skins of Resistance: Decolonising the Female Nude Through Practice Research with Young Women Artists.” Doctoral diss. Goldsmiths, University of London.

- Stengers, I. 2021. “Putting Problematization to the Test of Our Present.” Theory, Culture and Society 38: 71–92.

- Stern, D. 2010. Forms of Vitality: Exploring Dynamic Experience in Psychology, the Arts, Psychotherapy, and Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stewart, K. 2014. “Tactile Compositions.” In Objects and Materials: A Routledge Companion, edited by P. Harvey and H. Knox, 119–127. London: Routledge.

- Strom, K., J. Ringrose, J. Osgood, and E. Renold. 2019. “Editorial: PhEmaterialism: Response-able Research & Pedagogy.” Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology 10 (2-3). http://doi.org/10.7577/rerm.3649.

- Taylor, C., J. Quinn, and A. Franklin-Phipps. 2020. “Rethinking Research ‘Use’: Reframing Impact, Engagement and Activism with Feminist New Materialist, Posthumanist and Postqualitative Research.” In Navigating the Post Qualitative, New Materialist and Critical Posthumanist Terrain Across Disciplines, edited by K. Murris, 169–189. London: Routledge.

- Thomson, P., and C. Hall. 2021. “‘You Just Feel More Relaxed’: An Investigation of Art Room Atmosphere.” International Journal of Art & Design Education 40 (3): 599–614. 10.1111jade.12370.

- Timperley, V. 2020. Making Gender Trouble: A Creative and Participatory Research Project with Neurodiverse Teen Gamers. Cardiff: Cardiff University.

- Truman, S. E. 2021. Feminist Speculations and the Practice of Research-Creation: Writing Pedagogies and Intertextual Affects. London: Routledge.

- van der Tuin, I., and N. Verhoeff. 2022. Critical Concepts for the Creative Humanities. Washington, DC: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Welsh Government. 2020. "Cross-Cutting Themes for Designing your Curriculum." Hwb. [Online]. Available from: https://hwb.gov.wales/curriculum-for-wales/designing-your-curriculum/cross-cutting-themes-for-designing-your-curriculum

- Welsh Government. 2022. “Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE): Statutory Guidance.” Hwb. [Online] Accessed December 11, 2023. https://hwb.gov.wales/curriculum-forwales/designing-your-curriculum/cross-cutting-themes-for-designing-yourcurriculum/#relationships-and-sexualit y-education-(rse):-statutory-guidance.

- Wilson, H. F. 2019. "Contact Zones: Multispecies Scholarship Through Imperial Eyes." Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 2 (4): 712–731.