ABSTRACT

Thirty years after democracy in South Africa, the legacy of apartheid continues to affect Black and BrownFootnote1 bodies by excluding them from the ocean and other spaces through the legacies of racist laws which continue to bleed into the present. In this paper, I argue that strandlooping as a method of enquiry is key to understanding care for our hydrocommons. This methodology can also be considered to be a generative way of re-imagining and practicing higher education research and gender studies differently. Strandlooping as a lone, Brown woman along certain stretches of the coastline is unsafe, and this influences the way I work and whom I choose to walk with. I make use of African feminism, Indigenous knowledge and research-creation frameworks in the paper to enact theory-practice-praxis in creative and relational ways. The paper concludes with three suggested watermarks or propositions for strandlooping to encourage knowledge-making with humans and more-than-human entities.

1. Introduction

My research focuses on watery relations. We live on a blue planet and healthy oceans provide oxygen for us to breathe and survive. Oceans, rivers and wetlands are our natural water bodies which form part of the hydrological cycle and are our hydrocommons (Neimanis Citation2009). Hydrocommons refers to the water bodies and resources that we all use and for which we are responsible. Caring for our hydrocommons is critical for the health of the ocean, the planet and the humans and more-than-humans that reside here. However, there is tension with the concept of responsibility and who is responsible for caring for our common resources such as our water bodies. This tension arises because responsibility and care are linked to matters of justice, for which there are endless debates, theories and writings (Bozalek and Zembylas Citation2023). In South Africa, privilege and structural economic benefit was determined largely by skin pigmentation and this interplays with responsibility and care too. It follows that privileged irresponsibility, also referred to as ‘ignorant ignorance’ (Muthien and Bam Citation2021) is intertwined with power, and this power influences your ability to respond or what Bozalek and Zembylas (Citation2023) refer to as response-ability, which will be unpacked later in this paper.

One of the processes and enquiries I am using to understand responsibility and care is strandlooping along the False Bay coastline of Camissa.Footnote2 Instead of employing the term ‘walking,’ I've contextualized it by incorporating the creole Afrikaans word ‘strandloop,’ which means to beach walk, and appended the suffix ‘-ing’ to form a verb. Bam (Citation2021) refers to the word strandloper as a derogatory colonial term for the Goringghaicona who were seasoned, multilingual traders who travelled in passer-by ships way before the Dutch or Portuguese arrived at the Cape. As a Brown mixed-ancestry woman, I do not consider the word strandloper to be derogatory, and have in fact reappropriated and metabolized it; and have named myself ‘@contemporary_strandloper’ on Instagram. My mother has always proudly referred to herself as a strandloper having grown up along the False Bay coastline in a suburb called the Strand in the Western Cape, South Africa.

Strandlooping is a direct response and enactment that challenges the existing Western-based colonial research methods which have erased multigenerational knowledge of Indigenous women of the Cape (Muthien and Bam Citation2021). These Western disciplines seek ‘scientific objectivity’ through fixed terminologies and classifications leaving little room for fluidity and marginalized Indigenous women’s voices. I see strandlooping as an act to foreground ‘knowing differently’ and ‘doing differently’ in how we produce and understand relevant knowledge to arrive at an understanding that science is diffused with spirit, and that landscape speaks of stories denied (Bam Citation2021; Vollenhoven Citation2016). Strandlooping as a mode of enquiry offers direct insights into ways in which I am able to respond to the call to re-imagine and enact theory–practice–praxis in care-full, creative, and relational ways. Strandlooping for me happens alongside water in the liminal and littoral zones in South Africa but also along other countries’ coastlines and riverbeds. I include the practice of riverlooping which means walking along a freshwater river, another water body which ultimately meanders towards the salty ocean. This paper focuses particularly on the Camissa peninsula of False Bay, the Makhutsi river in the Limpopo province, and the Kawe (Cahuita) peninsula of Costa Rica. Tracking wild animals along the Makhutsi river opens up an understanding of how we share this planet with more-than-human species too.

The strandlooping takes place at either new or full moon and for the duration of this paper when I use the term strandlooping it also refers to riverlooping/swimming/kayaking/foraging. These lunar cycles give me the space to be a mother to my children and perform all the other roles I play in addition to thinking–feeling–doing–reading–writing for a doctoral degree. Many other long-distance walks (usually dominated by men) set out to achieve certain ambitions or targets in a linear, structured and time-limited way. Unlike this, strandlooping is done iteratively, in attunement and with consideration for the cycles of the moon, cycles of my body, the weather and swell predictions and the needs of my family.

This paper considers how we not only heal from our traumatic past through strandlooping as a contribution to social and educational change for plural ways of knowing, being and doing; it also challenges the traditional ways of learning and teaching in education. It does this by demonstrating how it might be done differently through innovative praxis and practical enquiries that I implement to co-develop a pedagogy of care for our hydrocommons in South Africa. In doing so, I am engaging in and being formed by feminist and collaborative knowledge-making processes, processes of becoming that stem from a relational perspective. Although I use the word ‘I’ in this paper, I am never alone. There are always the human and more-than-human entities that have contributed to my thinking and being in this world and other worlds (Barad Citation2007). This is the relational way I am trying to understand the world as I continue to break down the binary disciplined way I was trained to be in the world; and move to embrace a transdisciplinary way.

Black and Brown people bring together various sources and texts and narratives not to capture something or someone – to enslave them and universalize them – but to question the analytical work of capturing, and the desire to capture something or someone (McKittrick Citation2021). Whilst McKittrick uses the term interdisciplinary I prefer the use of transdisciplinary as described by Taylor, Hughes and Ulmer (Citation2020). Raghavan (Citation2020) in particular likens transdisciplinary feminism as seeking to disrupt the fortress-model of disciplinarity, and advocates for a transient disciplinarity, resisting entrenched disciplinary boundaries in favour of an expansive yet specifically situated approach. Furthermore, Ulmer (Citation2020) uses rust as a metaphor for transdisciplinary feminism as a means of describing the need to decay, corrupt and decompose disciplinary boundaries that seek to constrain our thinking. Given that I am strandlooping alongside the ocean and water bodies, the ocean in particular, has the ability to corrode and create rusty weatherings, this figurationFootnote3 resonates with me. This way helps me understand the commons to be a site of convening histories, knowledges, worldviews practices and wisdoms, that exist in stories. As Ulmer (2020, 238) reiterates, ‘rusty weatherings are not only figurative and literal in scope – they are also everyday expressions of hope for transdisciplinary feminisms yet to come.’ The paper published by Mohulatsi (Citation2023) expresses this understanding of the commons through her figuration of the watermeisie.Footnote4 Mohulatsi (Citation2023) argues that the watermeisie is a nomadic figure through whom we can attempt a speculative re-mapping of slave memory in Southern Africa, especially in the Cape region where slave-holding and trade were centred. The figuration of watermeisie invites us to think, notice and witness different ways of thinking-with and through the world, and in this particular body of work to think-with the oceans and rivers in an embodied way.

This embodied technique of strandlooping-with the ocean/river as water bodies and all the human and more-than-human entities is captured in this figure of watermeisie, and as I think with oceanic scholarly enquiries in relation to higher education pedagogies and gender. This way of viewing the commons lends itself to a relational ontology, which sees the world as inextricably entangled and holds that relations pre-exist entities, subjects and objects, which only come into being through relationships (Bozalek and Zembylas Citation2023). The idea of an independent, discrete, intentional and propertied individual human subject is troubled in a relational ontology. African feminism, Indigenous knowledges and research-creation, are seeking to find new possibilities to flourish and open-up opportunities for those who are marginalized in the current system by the intersectional and mutually constitutive oppressions of patriarchy, colonialism, and capitalism through artistic expression (Bam Citation2021; Knowles Citation2021). These three theoretical frameworks are relevant to relational ontology and this paper suggests that the practice of strandlooping and recognizing the world as relational, rather than static and binary, influences higher education and in turn this would re-form our intelligences to meet the world in a more caring, peaceful and less exploitative way (Tronto Citation2023).

The next stride of this paper will unpack the theoretical frameworks I have used to arrive at Afro-waterFootnote5 feminism.

1.1. Zig-zagging with African feminism, indigenous knowledges and research-creation as theoretical frames to arrive at afro-water feminism

My research enquiries are based on research-creation, and the nature of research-creation is that it emerged as a result of the enquiry related to inter – and transdisciplinarity through process philosophy (Manning Citation2016a; Truman Citation2022). Truman (Citation2022) elucidates the origins of research-creation in Canada, noting its adoption by artists and designers who blend artistic practice with elements of science or social science research. Additionally, scholars in various fields recognize the significance of arts and creativity, while educators seek to integrate cultural productions and arts-based pedagogy into curriculum development. Central to research-creation is the integration of artistic expression with academic enquiry, facilitating the generation of knowledge and fostering innovation through the convergence of creative and scholarly research methodologies. I am particularly drawn to rethinking how the artistic practice, of strandlooping in my case, reopens the question of what these disciplines can do, and how research-creation can enrich the understanding of the research question at hand (Manning Citation2016b). The strandlooping enquiry is outside of the disciplinary and institutional constrictions of co-creating a pedagogy of care for the hydrocommons and yet I argue that this makes strandlooping ideal for the research enquiry related to care, belonging, place-based concepts and healing. Strandlooping is a Slow process, and this means that the pace of my research enquiry is slower because of how walking informs thinking and writing and vice versa. Slow processes focus more on quality, on process rather than product, on curiosity and experimentation (Bozalek Citation2021). The slow process of strandlooping is key to addressing the research-creation of care for our environment through healing from our traumatic past; and building relationships with humans and more-than-human entities along the journey from Cape Point to HanglipFootnote6 (Hangklip).

The aim of this work is to reveal adapted and expanded ways of knowing that restore connectedness and relationality that culminate in contributing to finding other pathways for learning and teaching in higher education. My intention is to think through the principles of knowledge-making from a perspective that imagines a future that is unravelled from a patriarchal and colonial past; and to bring the entanglement of environmental and social justice issues to the surface. Tamale (Citation2020, 30) explains that this ‘is a multifaceted, holistic and integral process’ made more complex because of the redlinedFootnote7 colonialism’s legacy, resulting in a situation where ‘many in mainstream academia, even today, are yet to be convinced that feminist methodologies, approaches and analyses in research are part of legitimate scientific (or not) enquiry’ (47). The technique of strandlooping is used to engage in the enquiry by strandlooping-with as a movement of thought not only with others, but a process of engaging with obscured or marginalized histories, as described by Springgay and Truman (Citation2018).

Strandlooping is an active process, characterized by dynamic participation rather than passive observation. This active engagement, whether with oneself or in interaction with others, fosters dialogue and exploration without the constraints of predetermined hypotheses. By employing movement to stimulate thought, strandlooping allows ideas to unfold organically, without a predetermined endpoint. This process is inherently fluid and unpredictable, with outcomes subject to change over time. Drawing on Taylor’s (2020) conception of walking as a wavering line, strandlooping embodies a similar ethos. It is a meandering path that twists, turns, and intertwines with other narratives, eschewing the rigidity of linear thinking. This form of walking represents a departure from conventional discipline, embracing a feminist ethos of indiscipline. It is characterized by a refusal to adhere to norms or regulations, embodying a spirit of rebellion and autonomy. This non-linear approach is confirmed by Simpson (Citation2017) who writes about how Western education teaches us to type, write, and think within the confines of Western thought, as well as to pass tests and get jobs within the city of capitalism.

Leanne Simpson elaborates on how she learnt from a circle of Elders to proceed slowly and carefully – all of which are liabilities in a neoliberal university (Simpson Citation2017). Similarly, on a recent trip to Costa Rica, I visited Dr. Maria SuarezFootnote8 and was invited into a group of Elders called the Maternal Gift economy. Simpson (Citation2017) and Kimmerer (Citation2003) reiterate that the knowledge our bodies and our practices generate has never been considered valid knowledge within the academy and therefore often exists on the margins. The research enquiries I embody attempts to push against these margins and creates opportunities in higher education for embracing other ways of knowledge-making and reclaiming who I am as a Brown Creole woman, and opening up the space for others like me to also embark on this journey.

The strandlooping takes place along the seashore, within the liminal and littoral space and where tides wash between high and low. The environment is constantly changing and being churned, aerated if you will, and the plant and animal species that live in this shore zone need a special kind of resilience to withstand the wave action and exposure to the sun (Branch et al. Citation2022). Similarly, the riverlooping changes where I am able to walk depending on which section of the river I am walking. Our changing climate influences this too as is evident with the higher frequency of droughts and flash floods we have been experiencing across the globe (Zhou et al. Citation2023). I understand this resilience and it resonates with me and my positionality as a Brown Creole woman living through the latter years of our apartheid legacy, and then being the first of five Brown bodies in 1990 accepted into a school that was previously designated as Whites-only. Joining an integrated school was the beginning of my assimilation process and the need to belong. I have only broken this resilience to belong in my early 40s and in alignment with my decision to pursue my doctorate which has taken me on a journey of reclaiming who I am. The reason I use resilience and not enculturation, is because I have assimilated for so many years that it has almost transformed into a resilience of protection that ambiguously has not allowed me to feel into the realities of social ecological justice along my own coastline. The resilience sits inside of the assimilation.

Learning and reading about relational ontology has been a balm for my soul, having come from studying a science degree and struggling particularly with the subject and object binary that requires you as the researcher to divorce yourself from what is deemed as the experiment that you are observing. I have found home in strandlooping from a relational approach rather than a scientific positivist approach and enculturation which I learned, and am now unlearning, through categories and silos for my undergraduate and Masters studies degrees. This shift parallels my journey from assimilation and positivist methods to reclaiming my identity with ethical non-positivist paradigms. These paradigms embrace subjective interpretations and align with Indigenous and feminist knowledge systems, which are non-linear, non-rational, and value-laden (Tamale Citation2020).

I am drawn to African feminist theories that view relationships as inherently intellectual, spiritual and emotional. Ntseane (Citation2011) identifies four guiding ideas in African feminist research: a collective worldview, spirituality, shared knowledge orientation, and the role of gender in processing knowledge (Knowles Citation2021). I focus on the collective worldview, which balances individual and community needs, shaping problem recognition and responsibility. This intrigues me, especially regarding our hydrocommons. Care ethicists describe responsibility as acting on the identified need for care (Bozalek and Zembylas Citation2023). They explain that there are generally two different modes of responsibility – one grounded in the individual rational and moral agent, the other in collective or relational responsibility (Bozalek and Zembylas Citation2023, 8). Privileged irresponsibility or ‘ignorant ignorance’ (Muthien and Bam Citation2021) is about a refusal to acknowledge complicity and implicatedness in inequalities and unjust conditions. This ‘blind’ refusal allows certain groups/geopolitical areas and species to flourish at the expense of others. Bozalek and Zembylas (Citation2023) define the notion of response-ability, which involves responsiveness or the ability to respond. Response-ability involves paying close attention to the tracing of entangled relationships which are co-constituted with human and more-than-human others in multiple temporalities and spaces. We inherit various ghostly and material presences which continue to play out in the present and the future, such as the apartheid legacy of South Africa and more recently in Gaza. On the 17th of October 2023, the eleventh consecutive day of its bombardment, Israel stunned the world by bombing the al-Ahli Arab Hospital in Gaza City, where thousands of civilians were receiving medical treatment and seeking shelter from the attacks (Prashad Citation2023). How will we live with the ghosts that come to haunt us from the past and the future? Barad (Citation2017) writes that the indeterminacy of time and space is important when considering responsibility, privileged irresponsibility and response-ability, because the past and future are always already implicated in the thick-now of the present. As I strandloop along the False Bay coastline I carry an immense response-ability to hold the stories shared with me by the human and more-than human entities that I encounter along the way. I acknowledge that I may have more privileges than my Brown counterparts, and this enhances the weight of my response-ability on behalf of Brown and Black communities even more so. How do I ensure that the voices and stories of Black and Brown bodies are justly heard and shared despite my privilege?

The process of bringing together thinking with the hydrological cycle as watermeisie and hydrofeminism, with African feminism and Indigenous knowledge congeals into what I call Afro-water feminism. I found the term Afro-water feminism whilst drifting out at sea. I didn’t make it to the back; but it was this defeat and my salty, wet skin that opened up my thoughts to become entangled with all I had been reading, thinking, surfing and writing about African feminism and hydrofeminism. Afro also refers to a hairstyle originating with Black people, in which naturally curly or frizzy hair is cut into a full, round shape all over the head. There has been much written with regards to Black Afro hair and how swimming and being in water with hair that is curly becomes unmanageable which often leads to Black people not swimming or immersing themselves in water, in addition to all the other political entanglements that come with water and Black and Brown bodies (Erasmus Citation2000; Gumbs Citation2020). ‘Oe! My hare gaan huistoeFootnote9’: hair-styling as black cultural practice written by Erasmus (Citation2000) explains how scientific racism identified hair texture as a marker of racial heritage alongside skin colour.

Erasmus (Citation2000) concludes that race is always present, it is always there because whether we like it or not, we are still living in the shadow of the history of colonialism, slavery and genocide, and their cultural and political aftermath. The building swell of Indigenous knowledge, Afro-water feminism and research-creation allows us to work through and with the present deep wounds of injustice and environmental degradation with the possibility of healing with ancient salty water remedies. These frameworks advocate for learning that occurs relationally and in assemblages, rather than residing within individuals or entities (Gravett, Taylor, and Fairchild Citation2024). Learning is rather concerned with experimentation and the creation of concepts (a pedagogy of the concept) and the purpose of learning is not to transmit or acquire fixed objects or bodies of knowledge, instead learning in this way proposes that we muddle through concepts with human and more-than-human entities (Bozalek Citation2019; Lenz Taguchi Citation2010; Martin, Peers, and Giorza Citation2023b). The performative act of strandlooping along the coastline/river means that I cannot predict what I meet or what arises along the path. As such, I am strandlooping a concept (Springgay and Truman Citation2018) and I intend taking this further through suggesting strandlooping propositions or watermarks in this paper that will open up new processual ways of doing pedagogy which includes epistemology (knowing), being/becoming (ontology) and ethics (what matters) in relation to the ocean (Barad Citation2017).

In the next section of the paper, I bring you as the reader along on a few of my strandloops and in so doing I propose propositions/watermarks for strandlooping that will provide insights into practicing higher education that embraces Black/Indigenous and feminist scholarship.

1.2. Watermarks for strandlooping

Propositions or watermarks do not give information as to how they function in concrete instances, instead they gesture to how they could potentialize (Springgay and Truman Citation2018). Using watermarks as a figuration for propositions is relevant because they are literally out at sea and unstable in their nature, yet creating an awareness of shallower water or currents that sea users should avoid. Watermarks, as they drift in the waterways, can also be seen as springboards from which thought is composed to make space for the action to emerge. Given that this research is connected to the hydrocommons the use of the term watermarks as a figuration for propositions became relevant and poignant for conveying the prompts for strandlooping as a method of enquiry. Erin Manning and Brian Massumi (Citation2014), following Whitehead (Citation1947) refer to propositions as inflections or forces that influence what may come to be expressed in the process and how an incipient situation becomes open to be changed, intensifying or inhibiting it. In some ways, these watermarks are the springboards from which the strandlooping practice has evolved. These watermarks may not necessarily be useful to other scholars who chose to use a walking methodology because they are specific to my context; however, they may be useful to create and spark other watermarks applicable to scholars in their context. Painting with watercolours and leaving watermarks of colour of more-than-human entities that strandlooping brings me into contact with, is also a method I use to process my thinking. Below I unpack watermarks or propositions for strandlooping to encourage knowledge-making with humans and more-than-human entities.

1.3. The periwinkle harvest bag as container

I understand containers to be porous and have in fact described tidal pools as containers of care because of their porosity – water being able to flow through gaps in the walls and or over the top of the walls (Martin Citation2023a). Traditionally, the harvest bags for periwinkles were old onion bags because it was made from mesh netting that allows water to pass through, whilst acting as a container for the periwinkles without becoming too heavy with water whilst harvesting. Creating a container for myself to feel safe and connected has been important for allowing the enquiries to flow.

This notion of the carrier bag is echoed in author Ursula Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (Le Guin and Haraway Citation2019) which posits that even before the masculine spears and the hero/warrior archetype appeared in our cultural evolution there was the feminine carrier bag, which some considered our ancestors’ greatest invention. Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory suggests that all heroes, long before they can attempt their call to adventure, and express their agency were at one point contained in carrier bags whether in their mother’s womb, carried by the feminine, and had to experience care.

I had planned to strandloop at either new or full moon, so those dates were the actual event dates but it was important to walk in between and to give myself the space and time to process in preparation for the events. The regular practice of walking up our local mountain in Lakeside is the result of this. I have become acquainted with certain rocks and plants and one particular plant, the Protea Nitida, led me to my ancestors. I re-discovered how this plant played a role in a family-run business on Plein Street in Cape Town called Soeker and Soeker Bro’s for renting horses and carriages (Martin Citation2024). Ox wagon wheels were made from the Protea Nitida and the leaves were used to make plant dye. I have incorporated using the plant dye into the hydro-ruggingFootnote10 enquiry by dyeing the cloth that I use as a base onto which I am stitching and joining all the individual hydro-rugs and ocean memories shared (Martin Citation2024).

This watermark expresses the need to create a container, not in the conventional sense that is bounded and inflexible, but rather a container that allows for continuity and flow. This is akin to a feminist, relational ontology which allows for other ways of knowledge-making.

1.4. Feet as foundation for walking–feeling–thinking

Sometimes when you love the coast enough you become shoreline. (Gumbs Citation2020, 145)

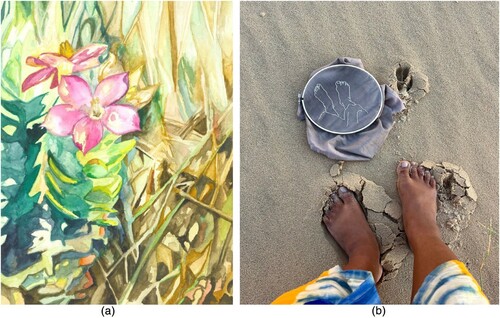

The very act of placing one foot in front of another mimics the movement, and creates the gentle rhythm of stitching/looping from strandlooping. Here the hyphen is used to emphasize the looping and the rhythmical motion. My strides become the invisible stitches along the coastline of False Bay as I gather stories through meeting humans and more-than-humans by re-connecting with coastline and remembering our ancestry – in particular the bodies affected by settler colonial histories and apartheid in South Africa. In (a), I came across a field of Sea Roses whilst walking along the rocky coastline at Pringle Bay looking for Drosters Gat.Footnote11 In addition to strandlooping, I have also been practicing drawing, painting, knitting socks and stitching to help me process my thoughts. The watercolour painting in (a). is an expression of how overwhelmed I felt by their beauty of these flowers and yet when I found the cave, and sat there to breathe and listen; I was deeply affected by the fear and pain that these forgotten souls endured as I listened to the waves rushing into and out of the cave below me. Like strandlooping, the watermarks I have made through painting help me process my thoughts by using more than my brain. This process of looping, painting and stitching are all springboards for opening up space to allow for more thoughts to flow in flexible, creative and innovative ways that are contrary to traditional knowledge practices. (b) is a photograph of my feet that I hand stitched onto Protea Nitida dyed cloth as a piece that will be added to the Mother Hydro-rug (Martin Citationforthcoming). Next to the wooden hoop, you may notice the footprints of a bushbuck that walked along the sand dune before I came along. This reiterates the relations with human and more-than-human entities as I strandloop. The stitched image of my feet is from a photograph that was taken whilst strandlooping along the Kawe and the realization that this watermark, feet as foundation for walking–feeling–thinking, is applicable wherever I strandloop as colonization has occurred globally and the segregation and separation of Black and Brown bodies is experienced globally. This will be unpacked further in the description of the last watermark.

1.5. Looping with intuition, attunement, curiosity and my MommyFootnote12

The places where strandlooping is practiced are where the learning takes place too. The importance of the material world, and in this case, the ocean and beach, plays a significant role in how we learn – the material is as important as the discursive, and cannot be separated from it (Bozalek Citation2019). Sometimes, this is set intentionally as a specific event and other times in the process of looping the learning arises spontaneously.

Mohulatsi (Citation2023) explains how Camissa holds memories that carry the history of colonization and apartheid, underscored by segregation and exclusions. These exclusions are felt and experienced elsewhere in the world too; as I experienced in Costa Rica on the Kawe coastline and in Portland, Oregon along the Nchi wana (Columbia) river. The divinities that occupy water also became modified, due to the histories of forced or semi-forced removal to which many people in South Africa, and the world, were subjected during colonization and more recently apartheid in South Africa and Gaza as depicted in a painting by my Mommy in (Biko Citation2017; Mohulatsi Citation2023). My Mommy and I spent a weekend together and I worked on writing this paper. When I had breaks from writing we would paint and draw together overlooking False Bay and chatting about my research and sharing stories. was painted by my Mommy as we sat together thinking and feeling with water. Strandlooping with the land and water bodies over new and full moons has been a practice of re-attuning with water and the celestial powers (Mohulatsi Citation2023). Painting and drawing have become an extension of the strandlooping and therefore a continuation of the practice of attunement and a creative expression of knowledge-making that is often overlooked in traditional higher education systems.

Around the time of the new moon in February 2023, I walked the stretch of coastline from Strand to Bikini Beach. Walking this stretch of coastline with my Mommy feels significant for me because she was born and grew up along this coastline. At the age of 11, her family was forcibly removed from their home living two blocks from the ocean, and only allowed access to certain stretches of the coastline that were often unsafe with sharp, jagged rocks and rip currents. My mom and I strandlooped together and came across the tidal pool she learnt to swim in as a child. The low tide had trapped at least 20 rays in the pool and we were able to watch them gliding and swim with them in the pool.

This encounter with the rays led me to read Barad (Citation2011) and they point out that the neuronal receptor cells in stingrays make it possible for these creatures to anticipate a message which has not yet arrived – a kind of clairvoyance – much like the intuition I need to listen to when planning the strandlooping enquiries. This practice disrupts linear time: past, present and future are threaded through one another. The act of strandlooping with my Mommy led us to meeting the rays and thinking with them has opened up how we learn from the more-than-human, disrupting the binaries of human/animal and listening with an open fleshiness towards the human and the more-than-human in order to anticipate the not-yet-thought or thought-in-the-act (Manning Citation2020). In the process of becoming with others or in relation to others, and staying with others for extended periods of time, we create trust, learning to hold possibilities open and discovering what we might become capable of together (Despret and Meuret Citation2016; Tronto Citation2015). According to Joan Tronto (Citation2015), trust refers to the duration of care and this resonates with the concerns that this paper is addressing regarding finding care-full ways of knowledge-making.

2. Congealings

In this paper, which surfaces processual knowledge, and strandlooping a conclusion is difficult, as the work is iterative ongoing. As such, I offer congealings as opposed to a conclusion. A thickening of insights and learnings. I have articulated the importance of different practices or enactments that are embodied, experimental, affirmative and inclusive, thus contributing to alternative knowledge-making in higher education. Through these embodied practices I am able to locate what I have termed Afro-water feminism – a practice that is similar to generative, playful, intuitive and inventive aesthetic practices of knowledge-creation and public pedagogies (Rotas Citation2016). This way of engaging with academic research undoes many of the assumptions implicit in higher education that focus on learning to teach in a categorized and segregated manner and which replicate systems of colonialism and apartheid. By emphasizing embodied, experimental, and inclusive practices, the paper advocates for a pedagogical shift towards relationality and processual learning. I have found processual knowledge-making with supervisors that extend beyond my academic supervisors to include my parents, immediate family members, citizens and more-than-human entities. This collaborative way of learning from both human and more-than-human entities is grounded in feminism and African/Indigenous frameworks.

In particular, this paper discusses the significance of strandlooping as a processual knowledge-making practice. It underscores how this approach expands ways of knowing, restoring connectedness between humans and more-than-human entities. By foregrounding the process over outcomes, rather than focusing on the outputs and measures of success and failure alone, strandlooping contributes to alternative pathways for learning and teaching in higher education. Furthermore, the strandlooping watermarks call for building flexible containers, containers of care (Martin Citation2023a) – thinking and feeling with your feet, listening deeply and re-mapping with your body. All of these watermarks are embodied enquiries that include epistemology, ontology and ethics – an ethico-onto-epistemological entanglement which encourages researchers to focus on becoming and what matters to them as opposed to focusing on epistemology alone. Whilst these watermarks are specific to my context, watermarks that pertain to other scholars can be devised by them and their context and needs. Embracing strandlooping as processual knowledge-making allows us to work with a sensibility that does justice to dispossessed people’s stories, that respects their knowledge, and de-centres colonial and apartheid knowledge agendas. As I strandloop with the ocean and the salty ancient water washes our wounds as it ebbs and flows between high and low tide watermarks; healing and slowly congealing wounds from the Black and Brown bodies of Camissa.

There are three watermarks that have been congealed here to assist researchers in crafting their own methodologies tailored to their specific contexts. The periwinkle harvest bag as a watermark captures the creation of a container that isn't rigid or restrictive but instead promotes continuity and fluidity. It aligns with a feminist, relational approach to understanding, which embraces diverse methods of knowledge creation. Feet as foundational for walking–thinking–feeling is a watermark that reiterates the looping and continuous movement that stimulates thought and emotion, ultimately enriching the writing process. Finally, incorporating intuition, attunement, curiosity, and personal connections, particularly with my Mommy, serves as a vital watermark in unlocking intuitive insights necessary for planning strandlooping enquiries.

Overall, the paper highlights the transformative potential of strandlooping as a feminist pedagogical and knowledge-making practice, surfacing its role in challenging dominant educational paradigms and centring marginalized voices and experiences.

Acknowledgments

Hanglip, Mommy, Kawe, Maria Suarez Toro, False Bay, Riyadh, watermeisie, my sons, Castle Rock, my feet, Makhutsi river, Viv and Dyl, Cape Point, Shark Spotters, beach plastic, Rah.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Aaniyah Martin

Aaniyah Martin is a PhD candidate at Rhodes University focusing on care for our hydrocommons, with sensitivity to Black and Brown bodies and our erased and forgotten relations with the environment. She has 22 years of experience in conservation. Locally, she is the founder of The Beach Co-op, at a continental level she joined the delivery team for the Women for the Environment in Africa leadership programme, and at a global level she is a member of the Homeward Bound faculty.

Notes

1 I use ‘Brown and Black bodies' instead of ‘Black Indigenous People of Colour' due to the North American framing imposed on South Africa. Stephen Bantu Biko’s Black consciousness ideas are more fitting for this work (Biko Citation2017).

2 Camissa, meaning 'place of sweet waters', was the Khoi people's name for Cape Town (Camissa Museum Citation2022). The city once had four rivers, including the Camissa River, and 36 springs, all of which were channeled underground and drained out to the sea as the city expanded.

3 Haraway (Citation1988) describes figurations as tricksters in that they blur the lines and boundaries of definitive ways of knowing and thinking-with concepts, they are aspirational responses to particular historical and material conditions.

4 The word watermeisie is Afrikaans referring to a kind of mermaid, a creature half-human and half-fish.

5 Water pronounced as ‘vaa-ter’, as one would say it in Afrikaans.

6 I research pre-colonisation place names, using Indigenous or earliest found names followed by current names in brackets. This act of remembering and reclaiming honours our ancestors.

7 A hiking/walking term that means you've hiked every single inch of trail in it. Here, it refers to the way in which colonialism is entrenched and found everywhere.

8 She is founder and director of ESCRIBANA, a feminist digital media venue since 2011. She was a co-director of the Feminist International Radio Endeavor (FIRE) from 1991 to 2011, of which she is a co-founder. She worked as an educator in literacy in many countries in Central America during the 1970s and 1980s. More recently, and what brought me to visit her, is that she is the coordinator of the Community Center Diving Ambassadors of the South Caribbean Sea, which is dedicated to archeological diving and recovery of the history of the afro-descendant population on the coast of Costa Rica.

9 Afrikaans for ‘Oh! My hair is going home’. A phrase used by Black and Brown people who have curly, frizzy hair that is uncontrollable especially when exposed to water.

10 Hydro-rugging is a research technique I use, centred on storytelling and the relationship between Black and Brown people and water. Participants share stories while stitching hydro-rugs from beach litter and other waste material. These will be attached to Protea Nitida plant-dyed cloth to create the Mother Hydro-rug, encompassing all the water stories.

11 Droster refers to a runaway slave and gat is a cave.

12 Using ‘Mommy’ instead of ‘Mother’ or ‘Mom’ is significant because it maintains a sense of intimacy and warmth, evoking childhood affection and our close bond. Our relationship has deepened through this research, allowing me to ask questions I wouldn't have during my assimilation phase.

References

- Bam, J. 2021. Ausi Told Me: Why Cape Herstoriographies Matter. Auckland Park: Jacana Media.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Barad, K. 2011. Nature's Queer Performativity. Qui Parle 19 (2): Spring/summer, 121–158.

- Barad, K. 2017. “Troubling Time/s and Ecologies of Nothingness: Re-Turning, Re-Membering, and Facing the Incalculable.” New Formations 92 (93): 56–86. https://doi.org/10.3898/NEWF:92.05.2017

- Biko, S. 2017. I Write What I Like. Johannesburg: Picador Africa.

- Bozalek, Vivienne. 2019. “Reconfiguring Academic Development Through Feminist Materialist and Posthuman Philosophies.” In Reimagining Curriculum: Spaces for Disruption by Lynn Quinn, edited by L. Quinn, 171–192. South Africa: Sun Media.

- Bozalek, Vivienne. 2021. “Slow Scholarship: Propositions for the Extended Curriculum Programme.” Education as Change 25:1–21. https://doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/9049.

- Bozalek, Vivienne, and Michalinos Zembylas. 2023. Responsibility, Privileged Irresponsibility and Response-Ability: Higher Education, Coloniality and Ecological Damage. Responsibility, Privileged Irresponsibility and Response-Ability in Contemporary Times: Higher Education, Coloniality and Ecological Damage. Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Branch, George, Margo Branch, Charles Griffiths, and Lynnath Beckley. 2022. Two Oceans: A Guide to the Marine Life of Southern Africa. Cape Town: Penguin Random House South Africa.

- Camissa Museum. 2022. What is the Meaning of Camissa? Camissa Museum. Accessed June 11, 2023. https://camissamuseum.co.za/index.php/orientation/meaning-of-camiss.

- Despret, Vinciane, and Michel Meuret. 2016. “Cosmoecological Sheep and the Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet.” Environmental Humanities 8 (1): 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3527704.

- Erasmus, Zimitri. 2000. “Hair Politics.” In Senses of Culture: South African Culture Studies, edited by Sarah Nuttall, and Cheryl-Ann Michael, 380–392. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

- Gravett, K., C. A. Taylor, and N. Fairchild. 2024. “Pedagogies of Mattering: Re-Conceptualising Relational Pedagogies in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 29 (2): 388–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1989580

- Gumbs, Alexis Pauline. 2020. Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals. Scotland: AK Press.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2003. Gathering Moss. Great Britain: Penguin Books.

- Knowles, Corinne. 2021. “With Dreams in Our Hands: An African Feminist Framing of a Knowledge-Making Project with Former ESP Students.” Education as Change 25 (1): 1–22.

- Le Guin, Ursula K., and Donna Jeanne Haraway. 2019. The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. London: Ignota Books.

- Lenz Taguchi, H. 2010. Going Beyond the Theory/Practice Divide in Early Childhood Education: Introducing an Intra-Active Pedagogy. London: Routledge.

- Manning, Erin. 2016a. The Minor Gesture. Durham.: Duke University Press.

- Manning, Erin. 2016b. “Ten Propositions for Research Creation.” In Collaboration in Performance Practice: Premises, Workings and Failures, edited by Noyale Colin and Stefanie Sachsenmaier, 133–142. Montreal: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Manning, Erin. 2020. For a Pragmatics of the Useless. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Manning, E., and B. Massumi. 2014. Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience. University of Minnesota Press.

- Martin, A. 2023a. “Tidal Pools as Containers of Care.” Ellipses Journal of Creative Research (IV). https://ellipses2022.webflow.io/article/tidal-pools-as-containers-of-care.

- Martin, A. 2024. “Collaborative Innovations Into Pedagogies of Care for South African Hydrocommons.” In Hydrofeminist Thinking with Oceans: Political and Pedagogical Possibilities, edited by Tamara Shefer, Vivienne Bozalek, and Nike Romano, 33–49. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

- Martin, A. forthcoming. Hydro-Rugging as Reparative Caring Encounter: Re-Membering Southern Oceanic Hauntologies. Re-submitted to Environmental Communications on 30 April 2024.

- Martin, A., Joanne Peers, and Theresa Giorza. 2023b. “Meandering as Learning: Co-Creating Care with Camissa Oceans in Higher Education.” Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning 11 (SI 2): 19–37.

- McKittrick, K. 2021. Dear Science and Other Stories. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Mohulatsi, M. 2023. “Black Aesthetics and Deep Water: Fish-People, Mermaid Art and Slave Memory in South Africa.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 35 (1): 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2023.2169909.

- Muthien, B., and June Bam. 2021. Rethinking Africa: Indigenous Women Reinterpret Southern Africa’s Pasts. South Africa: Fanele.

- Neimanis, A. 2009. “Bodies of Water, Human Rights and the Hydrocommons.” TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies 21:161–182. https://doi.org/10.3138/topia.21.161

- Ntseane, P. G. 2011. “Culturally Sensitive Transformational Learning: Incorporating the Afrocentric Paradigm and African Feminism.” Adult Education Quarterly 61 (4): 307–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713610389781.

- Prashad, V. 2023. The Palestinian People Are Already Free: The Forty-Second Newsletter. Accessed 19 October 2023.

- Raghavan, A. 2020. Inter(r)uptions: reimagining justice, dialogue and helaing. In Transdisciplinary Feminist Research: Innovations in Theory, Method and Practice, edited by C. Taylor, C. Hughes, and J. Ulmer, 153–167. Routledge.

- Rotas, N. 2016. “Moving Toward Practices That Matter.” In Pedagogical Matters: New Materialism and Curriculum Studies, edited by Nathan Snaza, Debbie Sonu, Sarah E. Truman, and Zofia Zaliwska, 179–196. New York: Peter Lang.

- Simpson, L. 2017. As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Springgay, S., and Sarah E. Truman. 2018. Walking Methodologies in a More-Than-Human World: Walking Lab. Abingdon & New York: Routledge.

- Tamale, S. 2020. Decolonization and Afro-Feminism. Ottawa: Daraja Press.

- Taylor, C., C. Hughes, and J. Ulmer. 2020. Transdisciplinary feminist research: Innovations in theory, method and practice. Routledge.

- Tronto, J. C. 2015. Who Cares? How to Reshape a Democratic Politics. New York: Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/cornell/9781501702747.001.0001

- Tronto, J. C. 2023. “Forward.” In Responsibility, Privileged Irresponsibility and Response-Ability: Higher Education, Coloniality and Ecological Damage, edited by Vivienne Bozalek and Michalinos Zembylas, v–viii. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Truman, S. E. 2022. Feminist Speculations and the Practice of Research – Creation: Writing Pedagogies and Intertextual Affects. New York: Routledge.

- Ulmer, J. 2020. Conclusion: the rusty futures of transdisciplinary feminism. In London and New York: Routledge.Transdisciplinary Feminist research: Innovations in Theory, Method and Practice, edited by C. Taylor, C. Hughes, and J. Ulmer, 237–247. Routledge.

- Vollenhoven, S. 2016. The Keeper of the Kumm. South Africa: Tafelberg.

- Whitehead, A. N. 1947. Essays in Science and Philosophy. Philosophical Library, Inc.

- Zhou, Jun, Chuanhao Wu, Pat J-F. Yeh, Jiali Ju, Lulu Zhong, Saisai Wang, and Junlong Zhang. 2023. “Anthropogenic Climate Change Exacerbates the Risk of Successive Flood-Heat Extremes: Multi-Model Global Projections Based on the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project.” Science of the Total Environment 889:164274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164274