Introduction

This special issue is conceived as a contribution to shifting the gravitational centre of globalised hegemonic knowledge about ‘mental health’ to perspectives from Abya Yala (Latin America) about ‘wellbeing’. This includes Hispanic and Francophone Caribbean islands where, for the most part, coloniality is still more of a present reality through the continued presence of the institutions, laws, state organs, and so on, of the colonial powers – as is most evidently the case, for example, of the US in Borikén (Puerto Rico) and France in Madinina (Martinique), where the békè (slave master descendent) is an entity that has no time nor space.

These lands have been subjected to successive colonial shifts. Following Enrique Dussel (Citation2007), we can speak of an Early or First Modernity (1492–1630), marked by the colonial transatlantic expansion and then slave ‘trade’, initiated by Portugal and Spain and quickly followed by the other European nations. The Second Modernity (1630–1789), saw the British empire, then the US empire, gain power through the industrial revolution – that, in some ways, relegated the south of Europe (Portugal, Spain, Italy and Greece) to the ‘Global South’ – and through the imposition of English as the international language, and Anglo-Protestant and capitalist modes of being expanding and becoming a fully fletched neo-colonial project; so called globalisation, which has reached almost all corners of the globe. The Monroe Doctrine, applied from the XVIII century following US and UK interests (with international policy amplified in 1904 by the Roosevelt Corollary), is a historical anchor of current practices. And in 1944, the US furthered its centrality through the Bretton Woods Agreement, which secured the dollar as the global currency.

Predictably, therefore, a brief genealogy of ‘mental health’ professions, including Psychology, makes evident that these disciplines, reproduced more or less critically in the different spheres (clinical, research, academic), are colonial, capitalist and imperialist in their origin and development. We cannot say that Psychology is Eurocentric, largely, it is ontologic and epistemologically anglo-andro-centric, that is, significantly dominated by White English-speaking men. However, despite this limited base, it has colonised (and continues colonising) psychological thought and practice globally. Hence, Martín Baró’s (Citation1994) urge to de-ideologise psychology and, more recently, a decolonising movement is gaining strength in social sciences and humanities.

Context

The Cuban Psychological Society organises the Intercontinental Convention of Psychology Hominis biannually since 1999. Hominis has a contemporary vision responding to the demands of Cuban Psychology, and inserted in the dynamic of the Cuban social project, with its successes, perspectives and future challenges. Its topics are inter- and multi-disciplinary, in order to delve into the dimensions of human beings in relation with their contexts, within their social and personal development; with the view to strengthen wellbeing and sustainability. Hominis edition IX has as central theme “Psychology working for the human wellbeing of the Peoples” (www.hominiscuba.com; https://www.scp.psico.uh.cu), and will take place from 26th to 30th April 2021 in the Palacio de Convenciones of La Habana, Cuba (www.eventospalco.com), with dialogues between diverse knowledges and professional in a fruitful intercontinental exchange.

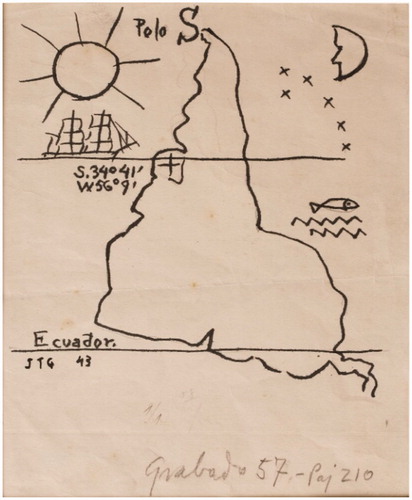

This special issue is borne out of a Roundtable organised by the first author, which took place during Hominis 2018 (Castro Romero et al., Citation2018), titled ‘Decolonising Psychology: Towards a New Horizon, New Epistemology and New Praxis’, following Martín Baró (Citation1994). This Roundtable, through its methodology, was in itself a praxis aimed at decolonising the conventional academic conference space: starting with four tellings/dialogues (in pairs); following by the audience/participants’ outsider witness practice (White, Citation1997); and closing with retellings from the Roundtable panel. Inspired by the work and words of Uruguayan artist and thinker Joaquín García Torres’ (Citation1941) call, we ‘inverted’ Psychology’s direction of travel:

América invertida (Inverted America, 1943)

“…because in reality our north is the South.

There cannot be a north, for us, but in opposition to our South. For this reason we now invert the map, so we have a fair idea of our position, not like the rest of the world wants. The tip of America, from now, prolonging itself, points persistently to the South, our north.” (1941, XX)

It is perhaps unsurprising that this decolonising effort took place in Cuba, a Caribbean island that, after the triumph of the Revolution in 1959, has resisted –and is resisting– continuous imperialist attacks, including the US imposition of an economic embargo since 1962, and has maintained a counter-hegemonic political and social option.

Apart from the colleagues who did the tellings (co-presented the Roundtable), we count with contributions of other scholars and practitioners who presented similar work at Hominis 2018, and others invited to this special issue to address wellbeing from various disciplines’ perspectives (i.e. psychiatry and sociology). We view colonialism and decolonisation as constructs in a continuum, from a more conventional (read Aimé Césaire, Citation1972) to a more radical position (read Frantz Fanon, Citation1986), and have included standpoints all along this continuum.

Structure

Congruent with the Roundtable –the seed from which we have reaped this special issue– we have clustered the critical contributions of our esteemed colleagues around three areas: a new horizon, new epistemology and new praxis, although invariably these aspects cannot be dissected and, therefore, we propose these are the different emphases of the articles.

To close, in an exclusive interview, Martinican sociologist Juliette Sméralda deconstructs the term decolonisation, examining re-colonisation and neo-colonisation processes, particularly in the French Caribbean, and proposes the development of reading grids for analysing and defining for oneself what is important to regain agency, respect and freedom.

New horizon

With a positioning within Abya Yala (Latin America), three articles offer an exploration of their local cartographies as a horizon – which is certainly not new but remains marginal within global Psychology – for us to look to as we engage in this process called decolonisation. In this first section, Renato D. Alarcón, Eduardo Gastelumendi and Alfonso Mendoza open this issue with a historical view of Peruvian Psychiatry’s search for identity through the examination of three key figures. Billie Turner and Sandra Elizabeth Luna Sánchez centre the legacy of colonialism on indigenous Mayan communities in Guatemala. And Guilherme Augusto Souza Prado contrasts coloniality with Brazilian Amerindian perspectivism to move psychology towards ecosophical care relations.

New epistemology

In this second part, we transcend the limits of current knowledge generation within psychiatry, psychology and allied professionals, opening possibilities to what can be known, to a plurality of knowledges (hitherto generally inferiorised), of afro-descendants, indigenous peoples and the feminine other. Yulexis Almeida Junco and Norma Guillard Limonta critique the colonial order through the position of Black Femism to recover the suppressed – through centuries of colonialism – knowledges of afro-Cubans. Rafael Sepúlveda Jara and Ana Maria Oyarce, bring forth new and old knowledge, proposing indigenous well-being concepts from Chile’s Mapuche people. From eastern Cuba, Aida Torralbas Fernández and Marybexy Calcerrada Gutierrez offer a gender perspective, decentring reason and centring emotion in the production of knowledges.

New praxis

The third section exemplifies the opportunities for decolonising through praxis – in the Freirean (Freire, Citation1970) sense of a cycle of action and reflection through which oppressed peoples can transform unjust structures – in three main areas relevant to psychologists and other allied professionals: research, therapeutic work and professional training. Manuel Capella Palacio and Sushrut Jadhav, employ ethnographic research in Ecuador as a tool to examine how coloniality shapes the making of Latin American Psychologists. Blanca Ortiz Torres describes a community-psychological practice with a marginal community in Borikén (Puerto Rico) after hurricane María. Finally, María Castro Romero and Manuel Capella Palacio share their liberatory pedagogic praxis within University contexts both in the UK and Ecuador.

Concluding remarks

From time immemorial colonisers forbade colonised peoples’ use of their own language as a form of domination. Language is one more tool of colonisation, for it not only (re)names (e.g. places, peoples) but in doing so the named is resignified and, as Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui (Citation2010) argues, obscured, and appropriated. Today, the use of English as the global language –the language of science but also of trade– is another sign of the strength of this practice. Thus, we have lost some meaning in translating from Spanish or through contributors writing in a language that is not their mother tongue and has different expressive limitations and demands for academia, which has been a complex issue to navigate but we hope to have accomplished a good balance. To redress this epistemic injustice, we will produce this special issue in Spanish in the near future and, in the current issue, for Hispanic and Lusophone authors, we have reclaimed an aspect of our identity through reinstating our two surnames –the first one inherited from the father, the second inherited from the mother– as separate, that is, without hyphenating (which is a practice in the English language, as people only inherit the paternal surname).

We think the timing of this special issue is right, given current world events, where a clear trace of colonisation can be observed in the hegemonic responses of governments across the globe, under the directions of the World Health Organization – the largest funders of the WHO are, first, the USA, then Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the UK, followed closely by ‘GAVI, The Vaccine Alliance’, also funded by Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (WHO, Citation2018). Unfortunately, but perhaps unsurprisingly, as we are about to go to print, the violence of White supremacy – concomitant with colonialism – is more and more present in images of abuses and killings of Black men and women. It is our wish for this decolonisation special issue to act as part of a counter-project to what Colombian indigenous peoples of Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta call colonialism’s and coloniality’s ‘death project’ (Suárez Krabbe, Citation2016, p. 3). We also wish to extend an invitation to colleagues in our area of work and further afield, including the people with whom we work in different contexts, to contribute to a ‘life project’, thinking about wellbeing of human and all in the natural environment from a multi-perspective and taking multi-level action towards social justice. Inasmuch as coloniality expressed itself differently across the globe, decoloniality must equally be locally grown, involving us all if it is going to be a shared new reality, co-created by people as equal actors in the world.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all contributors and the International Review of Psychiatry editors and staff, particularly, the support of Sadie and Susan Bigmore has been invaluable, in making this issue possible.

References

- Castro Romero, M., Melluish, S., Guillard Limonta, N., Torralbas Fernández, A & Capella Palacios, M. (2018). Decolonising Psychology: Towards a New Horizon, a New Epistemology and a New Praxis. Round Table at the 8th Intercontinental Convention on Psychology Hominis 2018: Human well-being and sustainable development: the place of Psychology. Havana, Cuba.

- Césaire, A. (1972). Discourse on colonialism. Monthly Review Press.

- Dussel, E. (2007). Política de la liberación. Historia mundial y crítica [Politics of liberation. Critical world history]. Editorial Trotta.

- García Torres, J. (1941). Universalismo Constructivo [Constructive Universalism]. Editorial Poseidón.

- Fanon, F. (1986). Black skin, white masks. Pluto Press.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogía del Oprimido [Pedagogy of the oppressed]. Siglo XXI.

- Martín Baró, I. (1994). Writing for a liberation psychology. Harvard University Press.

- Rivera Cusicanqui, S. (2010). Ch’ixinakax utxiwa. Una reflexión sobre prácticas y discursos descolonizadores [Ch’ixinakax utxiwa. A reflection about decolonising practices and discourses]. Tinta Limón.

- Suárez Krabbe, J. (2016). Race, rights and rebels. Rowan & Littlefield International Ltd.

- White, M. (1997). Narratives of therapists’ lives. Dulwich Centre Publications.

- World Health Organisation (2018). Voluntary contributions by fund and by contributor, 2017. Seventy-first World Health Assembly: WHO.