Abstract

In the past few decades, affirmative therapies for sexual minorities have burgeoned. These are appropriate therapies but often there is a lack of adequate research. We set out to study the research evidence available. For this mixed-methods review, we identified 15 studies looking into the experiences of lesbian, gay and bisexual people in psychological therapies. These included nine qualitative, five quantitative and one mixed method studies. Minority stress hypothesis may explain some of the major difficulties LGB individuals face. Studies showed computer based therapies may reduce or even eliminate unhelpful responses on part of the therapist. Challenges related to confidentiality and privacy in this context remain. Therapists may focus on minority stress but other stressors and not just discrimination may contribute to various mental health problems and their clinical presence. And finally, divergent findings found internalized homophobia may best explain discrimination-based minority stress and that therapist self-disclosure of own sexuality produced better results than the therapists who did not self-disclose. These findings are discussed and future directions for research are identified.

Background

The experience of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual (LGB) (sexual minority) populations and the use of psychological therapies is varied across the speciality (Johnson, Citation2012). Some look at a focus on symptom reduction as part of the experience, but others talk about not being validated. It is important to have a theoretical understanding of the experiences of the LGB population in psychological therapies. In a clinical setting, randomized controlled trials (RCT) are the important ones on which most clinicians rely to implement these therapies (Heck et al., Citation2017). RCTs are considered the gold standard but some would argue that they miss important information that can be gained via flexible treatment packages, inclusive criteria and more appropriate comparison groups (Abrahamson & Fairchild, Citation1999; Norcross, Citation2002; Westen et al., Citation2004). And it is the information gained in everyday clinic activity that can be easily captured using case study designs that can complement the robust RCT studies. It is, therefore, best to present a mixed methods review. This is needed to find studies that complement the established ideas, develop new themes and conclude with what studies have new insights, complement or diverge from the contemporary understanding of the experiences of LGB people in psychological therapies. In recent years, the use of mixed methods research syntheses (MMRS) in social and health sciences has increased in popularity (Barker et al., Citation2015). Some important purposes of completing an MMRS are to find new insights into data, complementarity, as well as divergence, along with exploring specific points for further development (Greene et al., Citation1989).

The period for this review of literature will focus on the knowledge between 1967 and 2021 and will be presented in a systematized fashion in three sections of quantitative studies, qualitative studies and mixed-method studies. The reason for starting in 1967 as this is the year that homosexuality was decriminalized.

Materials and methods

The search was performed using the search terms below. This included the criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies (Moher et al., Citation2009) to identify studies using participants that presented to primary care, improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) and other psychological/psychiatric centres for psychological therapy. The search terms can be seen in .

Table 1. Keywords used in search strategy.

A literature search was carried out by using electronic databases: In the initial electronic search, the following electronic databases were used to find relevant reports: EBM Reviews – Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005 to 6 February 2019, EBM Reviews – ACP Journal Club 1991 to January 2019, EBM Reviews – Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects 1st Quarter 2016, EBM Reviews – Cochrane Clinical Answers January 2019, EBM Reviews – Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials December 2018, EBM Reviews – Cochrane Methodology Register 3rd Quarter 2012, EBM Reviews – Health Technology Assessment 4th Quarter 2016, EBM Reviews – NHS Economic Evaluation Database 1st Quarter 2016, Maternity & Infant Care Database (MIDIRS) 1971 to December 2018, PsycINFO 1806 to February Week 1 2019, Books@Ovid 11 February 2019, CCCU Journals@Ovid Full Text, PsycARTICLES Full Text, Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions(R) 1946 to 12 February 2019, Social Policy and Practice 201901; PsycINFO, PubMED, EBSCO and open access sites at universities for Dissertations and Theses. The electronic search process was replicated four times between November 2018 and September 2021.

The inclusion criteria were LGB participants whose gender identity is the same as their sex assigned at birth or cisgender, and over 16 years old. Ethnicity and culture were considered but notwithstanding south Asian, Minority stress, adults, learning disabilities, IAPT, private health and charitable organizations, experiences of mental health services, experiences of professionals treating them. We excluded studies that included transgender/non-binary LGB, coming out research, psychological/psychiatric involvement in sexual orientation conversion therapy, transgender, experiences of mental illness, military, reducing stigma, informing counsellor training, homelessness and dementia. Also, studies having participants aged under 16 years old were excluded. All studies were processed through a software package for managing titles and abstracts to ascertain eligibility. If not clear, then a read of the whole study was carried out. Only studies meeting the inclusion criteria were kept. Data were extracted using a structured predefined tool and can be seen in and .

Table 2. All RCTs and quantitative studies included in the MMRS review of literature following an amended Cochrane protocol.

Table 3. Summary of participants that completed the study.

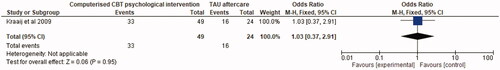

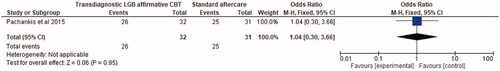

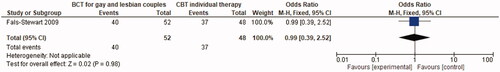

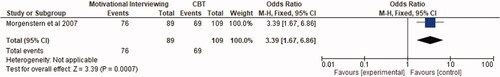

show the odds ratio of those participants who completed the treatment versus those who do not. If they stayed throughout, this suggests a positive experience. In terms of interpretation, the confidence interval (95%), suggests no association and when looking at the P value, it suggests insignificant association between the groups. and again suggests insignificant association but suggests a significant harmful association (P = 00007) of using the combined MI and CBT approach.

Results

The review found 15 studies and processed them in the segregated mixed-method synthesis. The review followed two processes. Firstly, a systematized review following the spirit of the Cochrane process for the quantitative part as shown by and CASP for the qualitative section, which can be seen in and . Most studies stayed with the usual labels of lesbian, gay and bisexual. Kraaij et al. (Citation2010) used the old-fashioned Victorian term of homosexuality and Morgenstern et al. (Citation2007) used the label of men who have sex with men (MSM). In this study, it was used as a wholesale term to include all groups together in one basket. Gay, bisexual, questioning and a cisgender straight man who likes to have sex with other men occasionally. This gets messy as the needs of the latter are specific and different from the other groups. Indeed, in some literature, the latter is the only group that is described as MSM. The problems are specific and require particular attention, which is different from gay, bisexual and questioning groups. This is an area not fully understood and in other literature is referred to as ‘buddy love’ or ‘bud sex’ further denoting a cisgender straight guy group who indulge in MSM with buddies/best friends. The reduction of symptoms is the main outcome measure. The participant self-reporting in most cases with the usual pre- and post-questionnaires. The experiences appear to be varied with the Rimes et al. (Citation2018) study showing no difference between gay and lesbian participants when compared with the cisgender heterosexual patients. In other studies, the participants did not understood, and in one study self -disclosure of the therapists aided the therapy journey. The assessment of the quality of transparency in resulted in four studies given the score of 1 (for good transparency) and two studies scoring 3 (inadequate and not transparent); n = 403 participants randomized in the five trials, and the outcome data about the reduction of symptoms during follow-up were available for n = 458. The service audit and feasibility study collectively had 10,963 participants. For quantitative studies, the actual participant number (centre figure) versus the actual number finishing the study (left-hand side figure) can be seen in .

Table 4. All qualitative and mixed methods studies included in the CASP.

Table 5. A breakdown of each study conducted in the CASP.

Discussion

In this section, we aim to describe the new insights, complementary findings and divergent findings reviews of a variety of studies from quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods approaches.

New Insights – This section addresses the new perspectives and insights, adding to a sense of completing the knowledge (Green et al., Citation2015). Also required is an objective stance, to step back and see the bigger picture while trying to understand the personal arena in which the phenomenon took place (Carroll and Rothe, Citation2010). That some are questioning the heteronormative framework that is dominant within the research world. Psychological therapies exist within this framework and some researchers are looking into new ways of understanding the LGB experiences via a new framework like the psychological mediation framework by Hatzenbuehler et al., (Citation2009). This framework alongside others may offer help LGB populations in identifying and labelling the experience but also may be a limitation. It appears that not all adverse experiences are always because of discrimination. However, a heteronormative stance does appear to always be an obstacle in the therapy experience (Grove, Citation2009). The use of computer based therapies using LGBT hero characters also appears to be a theme in the modern age. It appears to be one such approach that made significant changes to participants. Lucassen et al. (Citation2015) created a game that aided the player to collect points by carrying tasks that the participants felt helped them in real-life situations. This could be the route to cut out the unhelpful therapist interactions altogether. Unhelpful because they appeared insensitive to LGBT participants causing some to feel alienated as found by Israel et al (Citation2008). Kaysen et al. (Citation2005) questioned themselves about unconscious bias and addressed this by carrying out a reformulation during a case study. Applying specific data like disclosure of sexuality ID appeared to provide positive results. Initially, a social phobia diagnosis was applied but when reformulated to another conclusion (Walsh & Hope, Citation2010). This occurred in other studies too. It appears that this is a common phenomenon but is not clear from which direction this is generated. It could be that LGB people drive this if speaking in neutral terms to conceal their sexual identity or orientation, which then leads to staff concluding on a social phobia diagnosis. Hence, confusing symptoms between social phobia and minority stress, which is not yet a diagnosis in the DSM or ICD (Pachankis & Goldfried, Citation2006). The history of the hostility of health services to LGBT populations is well documented and maybe the best explanation for this concealment. Holley et al. (Citation2016) unfortunately found discrimination within the healthcare population today and suggest that this does contribute to the LGBT population feeling unwell for a longer period.

The other explanation is from the perspective of the therapist who formulates within a heteronormative perspective. This perspective is derived from the training received which primarily comes from often a dominant white male cisgender heteronormative perspective. This would best explain why the leaning towards a social phobia diagnosis occurs as it is the diagnosis that best explains some of the experiences of LGB people when rejected in social situations. On this point, training programs may need to consider amending a module to incorporate diversity communication using an LGBT framework of reference (Broadway-Horner & Kar, Citation2022). This would help with engagement and fine-tune person-centred care along the life span.

Complementary findings - Carroll and Rothe (Citation2010) contend that social science research has within its core the idea of complementarity supporting the ideas by Weber (Citation1949) of the importance of combining the objective with the subjective experiences for understanding human behaviour. Greene et al. (Citation1989) suggested that mixed methods are perfect for convergent validity via triangulation for transparency of the results thereby compensating for the limitations that a single study would have. Thus, complementarity would be achieved by using mixed methods to investigate the same phenomenon by offsetting the results into a pool of several researchers to provide a richer data type and stronger evidence.

This broadly sits within the psychological mediation framework by Hatzenbuehler et al. (Citation2009), addressing stresses from general sources and not discrimination based. It still incorporates aspects addressed by the minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003) from a discrimination viewpoint but also looks at other reasons for the stress not linked to discrimination alone such as family background, current work stresses, and relationship problems. But since the marriage act (2013), gay bashings have increased by 25%.

Divergent findings – According to Barker et al. (Citation2002) divergence in mixed methods research is a problematic feature. This is due to the contradictions and inconsistencies across the data sources that do not provide support in one direction but several possibilities.

Some literature states that the primary experience in psychological therapy is one of the discriminations but that would skew the whole picture (Israel et al., Citation2008). Not all experiences can be best explained under the discrimination viewpoint, as Pachankis et al. (Citation2015) point out. The CBT treatment focussed on minority stress but showed nil significance in reducing cognitive, affective, behavioural and emotional processes linked with the minority stress theory. The high transparency rating for the study helps to see that in this instance other factors were involved other than minority stress. Walsh and Hope (Citation2010) and Kaysen et al. (Citation2005) suggest to develop a specific framework or model in therapy just for LGB populations, but this review of the evidence does not appear to support this. Internalized homophobia was mentioned in some studies which may be useful to focus upon. This is a problem linked to specific family locations especially if born into fundamentalist religious organizations that preach against gay sexuality. Internalized homophobia has not been studied in any depth but may best explain the minority theory. Jeffery and Tweed (Citation2015) suggest that self-disclosure of the sexual orientation of the therapists may help the participants. They felt a sense of acceptance which may in turn help reduce or deal with internalized homophobia. This is yet to be proven but is interesting nonetheless as it provides another avenue for investigation and further exploration and will have an impact on self-disclosure which has traditionally been frowned upon in training programs, but Jeffery and Tweed (Citation2015) do put forward a convincing case for changes to be made to existing training programs.

Conclusion

The experiences of LGB participants in therapies have been varied and need some attention to ensure that affirmative therapies are available and accessible easily. The negative experiences appear to highlight issues in therapist training programs as well as in therapist sessions themselves leading some participants to feel alienated. The positive experiences show that when sexual orientation identity is used in the formulation needs are more likely to be met. This in conjunction with therapist self-disclosure may bring about an increased sense of compassion on part of the therapist as well as unconditional acceptance but may make the patient feel welcomed and accepted.

In accordance with Taylor and Francis policy and my ethical obligation as a researcher, I am reporting that I have no financial and/or business interests in or a consultant to; or received funding from any company that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper. I have disclosed those interests fully to Taylor & Francis, and I have in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Abrahamson, E., & Fairchild, G. (1999). Management fashion: Lifecycles, triggers, and collective learning processes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 708–740. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667053

- Barker, C., Pistrang, N., & Elliott, R. (2015). Foundations of qualitative methods.Research methods in clinical psychology: An introduction for students and practitioners (pp. 5-72). John Wiley & Sons.

- Broadway-Horner, M., & Kar, A. (2022). Our feelings are valid–reviewing the lesbian, gay, and bisexual affirmative approaches in a mental health setting. International Review of Psychiatry, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2022.2033180

- Carroll, L. J., & Rothe, J. P. (2010). Levels of reconstruction as complementarity in mixed methods research: A social theory-based conceptual framework for integrating qualitative and quantitative research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7(9), 3478–3488.

- Fals-Stewart, W., O'Farrell, T. J., & Lam, W. K. (2009). Behavioral couple therapy for gay and lesbian couples with alcohol use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 37(4), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2009.05.001

- Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737011003255

- Green, C. A., Duan, N., Gibbons, R. D., Hoagwood, K. E., Palinkas, L. A., & Wisdom, J. P. (2015). Approaches to mixed methods dissemination and implementation research: methods, strengths, caveats, and opportunities. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42(5), 508–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0552-6

- Grove, J. (2009). How competent are trainee and newly qualified counsellors to work with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients and what do they perceive as their most effective learning experiences? Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 9(2), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140802490622

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Dovidio, J. (2009). How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science, 20(10), 1282–1289.

- Heck, N. C., Mirabito, L. A., LeMaire, K., Livingston, N. A., & Flentje, A. (2017). Omitted data in randomized controlled trials for anxiety and depression: A systematic review of the inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85, 72–76.

- Holley, L. C., Tavassoli, K. Y., & Stromwall, L. K. (2016). Mental illness discrimination in mental health treatment programs: Intersections of race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(3), 311–322.

- Israel, T., Gorcheva, R., Burnes, T. R., & Walther, W. A. (2008). Helpful and unhelpful therapy experiences of LGBT clients. Psychotherapy Research : Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 18(3), 294–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300701506920

- Jeffery, M. K., & Tweed, A. E. (2015). Clinician self-disclosure or clinician self-concealment? Lesbian, gay and bisexual mental health practitioners' experiences of disclosure in therapeutic relationships. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 15(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12011

- Johnson, S. D. (2012). Gay affirmative psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: Implications for contemporary psychotherapy research. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(4), 516–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01180.x

- Kaysen, D., Lostutter, T. W., & Goines, M. A. (2005). Cognitive processing therapy for acute stress disorder resulting from an anti-gay assault. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 12(3), 278–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1077-7229(05)80050-1

- Kraaij, V., van Emmerik, A., Garnefski, N., Schroevers, M. J., Lo-Fo-Wong, D., van Empelen, P., Dusseldorp, E., Witlox, R., & Maes, S. (2010). Effects of a cognitive behavioral self-help program and a computerized structured writing intervention on depressed mood for HIV-infected people: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 80(2), 200–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.08.014

- Lucassen, M. F., Hatcher, S., Fleming, T. M., Stasiak, K., Shepherd, M. J., & Merry, S. N. (2015). A qualitative study of sexual minority young people’s experiences of computerised therapy for depression. Australasian Psychiatry : Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 23(3), 268–273.

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., Altman, D., Antes, G., … Tugwell, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement (Chinese edition). Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine, 7(9), 889–896. https://doi.org/10.3736/jcim20090918

- Morgenstern, J., Irwin, T. W., Wainberg, M. L., Parsons, J. T., Muench, F., Bux, D. A., Jr, Kahler, C. W., Marcus, S., & Schulz-Heik, J. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of goal choice interventions for alcohol use disorders among men who have sex with men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(1), 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.72

- Nel, J. A., Rich, E., & Joubert, K. D. (2007). Lifting the veil: Experiences of gay men in a therapy group. South African Journal of Psychology, 37(2), 284–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124630703700205

- Norcross, J. C. (2002). Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients. Oxford University Press.

- Pachankis, J. E., & Goldfried, M. R. (2006). Social anxiety in young gay men. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20(8), 996–1015.

- Pachankis, J. E., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Rendina, H. J., Safren, S. A., & Parsons, J. T. (2015). LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 875–889. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000037

- Rimes, K. A., Broadbent, M., Holden, R., Rahman, Q., Hambrook, D., Hatch, S. L., & Wingrove, J. (2018). Comparison of treatment outcomes between lesbian, gay, bisexual and heterosexual individuals receiving a primary care psychological intervention. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 46(3), 332–349. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465817000583

- Satterfield, J. M., & Crabb, R. (2010). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in an older gay man: A clinical case study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17(1), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.04.008

- Tan, E. S., & Yarhouse, M. A. (2010). Facilitating congruence between religious beliefs and sexual identity with mindfulness. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(4), 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022081

- Walsh, K., & Hope, D. A. (2010). LGB-affirmative cognitive behavioural treatment for social anxiety: A case study applying evidence-based practice principles. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.04.007

- Weber, M. (1949). The methodology of the social sciences. Translated and edited by Edward A. Shils and Henry A. Finch. (Rainbow-Bridge Book Co. 1971), 115.

- Westen, D., Novotny, C. M., & Thompson-Brenner, H. (2004). Thompson-Brenner. (2004). The empirical status of empirically supported psychotherapies: Assumptions, findings, and reporting in controlled clinical trials. Psychological Bulletin, 130(4), 631–663.