Abstract

Sexual minorities (individuals with a lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, or other non-heterosexual identity) are at elevated risk of developing common mental health disorders relative to heterosexual people, yet have less favourable mental health service experiences and poorer treatment outcomes. We investigated the experiences of sexual minority service users accessing mental health services for common mental health problems (e.g. depression or anxiety) in the UK. We recruited 26 sexual minority adults with experiences of being referred to Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) or primary care counselling services. Semi-structured interviews explored participants’ experiences of service use and views on service development. Interviews were analysed using thematic analysis. Barriers to effective relationships with practitioners included service users’ fears surrounding disclosure, and practitioners’ lack of understanding and/or neglect of discussions around sexuality. Regarding service development, participants highlighted the value of seeing practitioners with shared identities and experiences, visible signs of inclusivity, sexual minority training, tailored supports, and technological adjuncts. Our findings offer insights into possible contributory factors to treatment inequalities, and highlight potential methods for improving service provision for sexual minorities.

Introduction

Individuals with a lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, or other non-heterosexual identity (collectively known as LGBQ + or sexual minority individuals) are disproportionately affected by psychological disorders relative to heterosexuals. Sexual minorities have at least a 1.5 times higher risk of common psychological disorders (e.g. depression and anxiety), as well as substance dependence and suicidality (King et al., Citation2008; Plöderl & Tremblay, Citation2015).

In keeping with their disproportionate burden of psychological disorders, sexual minorities utilise healthcare services more frequently than heterosexuals. This includes primary care consultations, as well as both psychotherapeutic and pharmacotherapeutic treatments for mental health problems (Bränström et al., Citation2018; Chakraborty et al., Citation2011; Cochran et al., Citation2017). Despite greater treatment uptake, sexual minorities are more likely than heterosexuals to report unfavourable treatment experiences (Blosnich, Citation2017; Elliott et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, relative to heterosexual people who receive treatment for common mental health disorders, sexual minority women and bisexual men have a lower likelihood of attaining reliable recovery, and are more likely to finish treatment with higher final-session severity scores on measures of depression, anxiety and functioning in England’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services (Rimes et al., Citation2019). There has been little large-scale treatment outcome research in other countries. Research using single-service providers in USA, Canada and Austria has reported mixed findings regarding disparities in treatment outcomes for sexual minorities (Beard et al., Citation2017; Donahue et al., Citation2020; Plöderl et al., Citation2017).

Addressing disparities in satisfaction and outcomes requires an understanding of their causes. Studies investigating sexual minority adults’ experiences of mental health services found that participants reported prejudice and discrimination, reluctance to disclose sexual orientation, problems around discussion of sexual identity in treatment, and inadequate clinician awareness and understanding (Ferlatte et al., Citation2019; Foy et al., Citation2019; Mccann & Sharek, Citation2014). However, research exploring these barriers in England’s IAPT and primary care counselling services is currently limited to online surveys, and has not been triangulated with interviews with sexual minorities which explore how such barriers affect therapeutic relationships. The present study used semi-structured interviews to investigate two areas in more depth:

The experiences of sexual minority adults who attempted to access and receive psychological interventions via IAPT or primary care counselling services for mild to moderate psychological problems. In particular, we were interested in exploring how participants’ sexual minority identities may have created barriers to favourable treatment experiences and outcomes, and how such barriers affected therapeutic relationships.

Service users’ views on how services may be developed to achieve optimal experiences and outcomes for sexual minority individuals with psychological difficulties.

Materials and methods

Participants

Twenty-six participants were recruited to the study. Eligibility criteria are listed in .

Table 1 Eligibility criteria.

Procedure

Sexual minority individuals were recruited through purposive sampling via social media, mental health websites and sexual minority community groups. Prospective participants were invited to complete a semi-structured interview investigating their experiences of being referred to, or receiving, NHS care for mild to moderate psychological problems (e.g. anxiety, depression or stress). Interested individuals were given an information sheet to read, completed an expression of interest form and gave informed consent. Two researchers (DM and VF) assessed participants for common mental health disorders and serious mental illness (i.e. schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or anorexia nervosa) using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (First et al., Citation2015). Participants who did not meet eligibility criteria were excluded. Eligible participants completed an audio recorded telephone interview with either DM or VF exploring their experience of primary care and/or IAPT services.

Interviews

To address our specific research aims, questions focussed on (1) whether participants had any expectations of stigma or discrimination prior to accessing support, and the extent to which these expectations were borne out; (2) whether their sexuality played a role in their experience of treatment, including: the extent of sexual orientation disclosure, the relevance of their sexuality to their presenting problems and whether therapists asked about such issues; (3) how services could better serve sexual minority people. Semi-structured interviews were then developed. Where closed questions were asked, interviewers used prompts to elicit further information, particularly around how experiences affected therapeutic relationships.

Data analysis

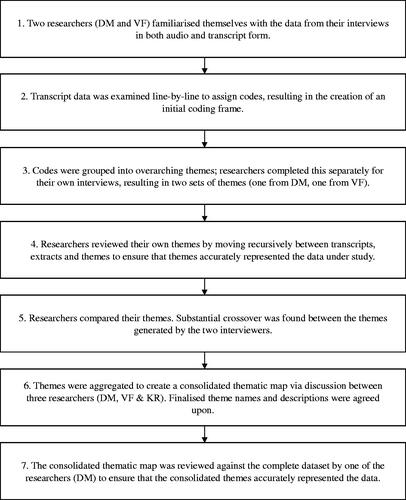

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, anonymised and analysed by DM and VF using a qualitative software package (NVivo 10). Thematic analysis, following a critical realist approach, was conducted in a seven-stage process adapted from Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) and outlined in .

Figure 1. Seven-stage process used for thematic analysis, adapted from Braun and Clarke (Citation2006).

Reflexivity statement

Researchers considered and logged the perceived influence of their own identities and experiences on the research process prior to and after conducting interviews and data analysis. Both interviewers (DM and VF) possessed sexual minority identities and were familiar with theoretical understandings of sexual minority mental health via previous psychology degrees. Their supervisor, an academic clinical psychologist (KR), read interviewer’s reflexivity accounts and discussed the influence of their views, backgrounds and experiences with them prior to and after the interviews.

Ethics

The study obtained ethical approval from the King’s College London Psychiatry, Nursing and Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee, reference HR-15/16-3369.

Results

Participant characteristics

Participant demographics are summarised in Appendix 1. Of the 7 gay participants, 6 (85.7%) identified as men and 1 (14.3%) as a genderqueer man. Of the 9 lesbian participants, all identified as women. Of the 6 bisexual participants, 2 (33.3%) identified as men and 4 (66.7%) women. Of the 3 queer participants, all identified as women. One pansexual participant identified as a man.

Results of thematic analysis

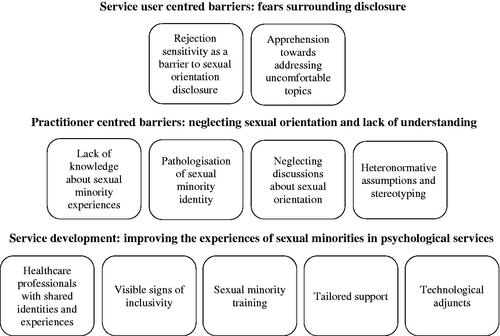

Themes and subthemes are summarised in a thematic map in .

Service user centred barriers: fears surrounding disclosure

Two subthemes were identified regarding service user centred barriers.

Rejection sensitivity as a barrier to sexual orientation disclosure

Participants emphasised that disclosure of sexuality can be challenging due to fears of discrimination, unconscious bias or stereotyping. One participant said: ‘I’m always looking for how someone’s going to react when I say it, because it’s not something you can tell from just my appearance’ (participant 27). This fear persisted even if there was no perceptible evidence that practitioners held these views. One participant explained this by stating that most sexual minorities ‘probably have been judged previously, and it’s that fear of that happening again’ (participant 17). Bisexual participants relayed concerns that practitioners would brand them as confused, attention-seeking or hypersexual.

These fears were apparent across all stages of the care pathway. Participants believed this may have consequences for the health outcomes of sexual minorities and influence whether individuals who need support end up accessing services: drawing on personal experiences, participants described how this impacted both their decision-making around accessing support, as well as their ability to fully be themselves after accessing it.

I think the prospect of being hated when so many people probably will have hated themselves for a long time because of it, it’s so scary that I would say that that’s the biggest inhibition to seeking help - it’s just that, that fear of, of judgement - negative judgement. (participant 16)

I do feel to an extent, not probably from the therapist side but from my own side, it [their sexual minority identity] does affect trust … it’s a little bit uncomfortable to be that vulnerable with somebody when you don’t really know whether or not they’re going to be accepting of you. (participant 14)

Apprehension towards addressing uncomfortable topics

Even when participants felt confident enough to disclose their sexuality, some topics relating to their sexual minority identity remained challenging to discuss. One participant described this as an ‘additional fear of different aspects of my life not being understood’ (participant 26). These topics often focussed on romantic and physical intimacy as a sexual minority person: ‘especially if you’ve been in the closet for a long time, then, you know, you’re not used to talking to other people about sex, about gay sex.’ (participant 25). Participants’ discomfort was often significant enough that such discussions would not take place at all.

Practitioner centred barriers: neglecting sexual orientation and lack of understanding

Four themes were identified regarding barriers originating from practitioners.

Lack of knowledge about sexual minority experiences

A number of participants expressed that non-sexual minority practitioners often lacked an understanding about sexual minority experiences, specifically knowledge around: definitions of sexual minority terminology; sexual minority identities beyond lesbian, gay and bisexual orientations; problems frequently faced by sexual minorities (for example common health concerns and relationship issues); and the heterogeneity of this population. Some participants highlighted the need for therapists to understand that stressors may originate from sexual minority communities themselves rather than exclusively from heterosexuals:

a lot of bisexual people face actual discrimination from the wider LGBT population, and some friends of mine have been told by lesbians that they’re just greedy, or … not properly part of the community. (participant 25)

Participants emphasised the importance of such knowledge to open, trusting relationships between practitioners and service users. Consequently, due to a perceived lack of knowledge participants felt ‘more guarded’ (participant 1), perceived practitioner’s empathy to be lacking, and felt misunderstood. The effect of this was undermined psychotherapeutic support: ‘I had to waste so much time in the sessions trying to explain things’ (participant 3). Other participants even felt that attempting to explain these issues would be a fruitless endeavour: ‘there’s certain things that I feel like it would just take way too long to explain to somebody who’s straight, and then they probably wouldn’t really believe you anyway.’ (participant 14).

Pathologisation of sexual minority identity

Several participants voiced dissatisfaction with practitioners’ assumptions that all their presenting issues related to their sexual orientation. While participants emphasised that this suggestion was not always erroneous or unhelpful, this generalised assumption became an obstacle to progress when practitioners persisted with this belief in the absence of any confirmation from the service user. Some practitioners brought up this link so frequently that it left participants with a feeling that their sexuality was perceived as inherently pathological and that their mental healthcare needs were subsumed in their sexuality:

it’s constantly brought up as some sort of like mental illness within itself … [we] would go into this massive like… journey about my sexual orientation, and yeah of course there are some issues but the way they talk about it … they make it seem like I’m some sort of, like oddity and that it’s not normal … a lot of them their tone would change, and it would become the focus of the session when in reality I’ve had a lot more issues going on. (participant 24)

The most damaging instances of this occurred when practitioners pursued this despite clear refutation from the participant. Some participants emphasised that this ‘therapist knows best’ mentality was a hindrance to their recovery:

I would try to express that they [sexual minority identity and mental health condition] weren’t connected, but being a mental health professional they may have felt that they were in a better position to know … rather than trying to explain what the situation is, you end up explaining why that it’s not another situation. (participant 10)

Neglecting discussions about sexual orientation

In contrast to above, participants felt that some practitioners were reluctant to acknowledge their sexual minority identity and its relevance to their mental health. Multiple participants expressed that ‘there was never any room for it in my therapy’ (participant 20). Participants suggested that this was attributable to: insecurities around being able to confidently address sexual minority issues; awareness of the complicated historical pathologisation of same-sex attraction within psychiatry; or an underestimation of the challenges associated with being a sexual minority.

[there is] a tendency … to just kind of disregard things that they find a bit uncomfortable to deal with … I think he kind of, tactfully as possible, kind of ignored it as much as he could because he didn’t feel like it was something that he could really help me with. (participant 14)

it may be that they’re uncomfortable about the orientation itself, but I suspect it’s not so much that as it’s they don’t want to be seen to be trying to ‘cure me’. (participant 2)

I think I was made to feel like my issue wasn’t really an issue, it was just part-and-parcel of life, and I guess in some ways, I was made to feel like I was overreacting. (participant 1)

Not all participants felt that ignoring sexuality was detrimental to the quality of therapy: ‘I remember one therapist saying ‘well let’s just leave that gay stuff alone’, and actually it was very good at helping me, because it was very much based on a behaviourist model’ (participant 2). However, other participants felt that practitioners’ reluctance to address sexuality starved them of the opportunity to feel ‘more seen’ (participant 14) and address topics central to their presenting issues: ‘because they were … wanting to be politically correct, or not wanting to ask the wrong question, they also didn’t ask the right question [about their sexuality]’ (participant 26).

Heteronormative assumptions and stereotyping

Some participants experienced dissatisfaction with preconceived notions possessed by practitioners. Firstly, heteronormative assumptions were made prior to disclosure of their sexuality. Participants felt that ‘you are assumed to be straight or cisgender, until told otherwise’ (participant 14) led to incorrect assumptions that required time and energy to dispel and precluded valuable discussions about sexuality. One participant said: ‘they come at you with a list of assumptions that you don’t necessarily fit if you belong to a sexual minority, and it’s kind of hard to navigate not, not fitting their assumptions and still trying to explain other areas.’ (participant 10). This was particularly the case for bisexual participants: ‘I remember it [sexuality] never coming up because people made assumptions, especially … when I identified as bisexual and I was in a … relationship with somebody of the opposite gender.’ (participant 20).

Secondly, following disclosure of their sexuality, some participants felt that practitioners demonstrated unhelpful stereotypes, assumptions and judgments; one participant explained:

she essentially outlined how she felt that gay men don’t settle down until their late thirties, maybe forties, and keeping options open, playing the field, if you will… at the time, I was just like ‘I just want some help’, but in retrospect there is definitely quite a lot of issue with that, with what she said, in terms of prejudice and stereotype … an implied stereotype of a promiscuous community. (participant 1)

Participant accounts suggest that assumptions and stereotypes can have profound consequences for therapeutic relationships: ‘I’ve had to change psychologists quite a lot because of what they’re telling me’ (participant 24); another observed that ‘for some people it can be a problem - it can prevent people getting help.’ (participant 17).

Service development: improving the experiences of sexual minorities in psychological services

Five themes were identified regarding how psychological services could be improved to better address sexual minorities’ needs.

Healthcare professionals with shared identities and experiences

When asked about their preferences regarding the gender and sexuality of their therapist, participants expressed a range of opinions. Preferences were largely informed by a desire to feel understood and avoid discrimination. For most participants, this meant a preference for practitioners who possessed a sexual minority identity or lived experience of discrimination. However, participants’ motivation to feel understood and avoid discrimination did not always translate into a desire to see a therapist of the same gender. One participant who identified as a man stated:

I think I would find it difficult for [me to be treated by] … a white heterosexual, cisgender male. I think they would have difficulty empathising with anyone in a minority who has experienced discrimination at any point in their lives, and being able to understand the difficulties. (participant 1)

Despite this being a clear and recurrent theme, some participants held discrepant views. These participants expressed that what mattered most was practitioners’ ability to understand and empathise with their experience: ‘At the end of the day it’s still the ability of the person that you’re talking to that’s the most important thing. Just because someone just happens to be gay – they might be the worst doctor in the world.’ (participant 5). Indeed, some participants found that while they came to therapy with negative expectations due to their therapist’s sexuality or gender, these expectations were dispelled:

I had very serious reservations about, being in therapy with a male therapist, but he was wonderful … I think my expectations were changed by experience, so I think … if I needed to seek help again, I would probably just think of it as, well, are they any good? (participant 14)

Visible signs of inclusivity

Given that sexual minorities often hold concerns about judgement, prejudice and stereotypes, participants expressed a wish for healthcare providers to ‘make it clear that there’s going to be no discrimination against somebody because they’re LGBQ+’ (participant 5). Participants also felt that services needed to move beyond proving an absence of discrimination, and instead move towards visible indicators that they are welcoming of sexual minority service users and equipped to support with sexual minority issues. Participants believed this could counteract service users’ pre-existing concerns.

Participants had a variety of ideas as to how services might visibly display their inclusivity. This included provision of information about practitioners’ training and experience and signposting to sexual minority specific services in the form of posters or pamphlets.

Sexual minority training

Participants highlighted the need for all practitioners to undergo training in supporting sexual minority service users. One participant felt that ‘the issue with a lot of mental health professionals is that they just aren’t trained or knowledgeable in the area at all’ (participant 10).

Participants believed that practitioners should understand different identities within the sexual minority spectrum and appropriate versus inappropriate language:

Terminology is a massive thing that I think people who aren’t in the community don’t know. In society sometimes there are understandings of a certain word that don’t actually relate to the way it’s used by the majority of LGBT people, so education as to what words actually mean to people when they use them. (participant 10)

Participants also highlighted the advantages of educating practitioners about the uniquely challenging experiences faced by many sexual minority service users (in particular coming out and discrimination), and how these impact thoughts and emotions. Some participants believed that exploration of this may contribute to treatment success: ‘It could not be an issue for that person, but how does the therapist know unless they ask? And how does the person know, unless they are asked?’ (participant 13).

While participants acknowledged the importance of education about commonalities across sexual minority service users, they believed that training must avoid inadvertently reinforcing sweeping generalisations about sexual minority service users and their treatment needs. Participants expressed that ‘feeling accepted’ (participant 11), ‘normal, and natural’ (participant 12) are fundamental to the development of a strong therapeutic relationship. As such, training should also ‘focus on the diversity of [sexual minority] people’s lives and experiences’ (participant 26), and how practitioners need to tread a fine line when thinking about whether sexuality plays a role in a sexual minority person’s difficulties.

Tailored support

Participants believed that service users would benefit from staff and services specialising in supporting sexual minorities. Given that many sexual minorities share similar experiences, issues and concerns, a specialist service would help to: ‘streamline the service and help take pressure off [other services]’ (participant 1), reduce anxiety around potential prejudice or discrimination, and encourage sexual minorities to seek support earlier:

The reason I didn’t seek help earlier was because when I was abroad there were no tailored services for LGBT people, so it felt like I would anticipate some discrimination in those situations, and I think the same here in smaller cities where maybe it’s harder to find specifically tailored services for LGBT people. (participant 4)

Participants were asked about particular types of sexuality-specific support that could be offered. Firstly, participants highlighted the value of: one-to-one therapy, designed specifically for sexual minority individuals; group therapy, to bolster social support that may not otherwise exist; and both partner and family-based support, to facilitate understanding, acceptance and communication.

Technological adjuncts

Participants noted the potential benefits of a variety of technological adjuncts to therapy. Firstly, participants suggested that online support groups could increase accessibility of support for individuals who feel unable to attend face-to-face groups: ‘I was very scared to then go and meet other people that were very similar … so probably online would’ve been maybe a more comfortable way for me to do that’ (participant 21).

Secondly, participants felt that video content held potential for helping sexual minorities feel that ‘actually I’m not alone … other people are suffering from the same things … [that] would be really useful for a lot of people.”’(participant 6). However, there was a feeling that videos would have to differentiate themselves from existing online content. Participants suggested that videos should combine informal, first hand-accounts from sexual minorities who have experienced mental health problems with structured, problem-specific, evidence-based, and goal-oriented self-help tips that are ‘accessible … quick, and … easy to digest’ (participant 23). Suggested topics included coming out as gay in a heterosexual marriage, fostering self-acceptance and domestic violence in sexual minority relationships.

Thirdly, participants supported the prospect of a mobile app collating multiple methods of improving sexual minority mental health, including: online groups and forums; video content; signposting; Q&As with practitioners; and sexual minority-tailored cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness techniques.

Participants consistently expressed that online services should complement rather than replace face-to-face support, which offered a variety of irreplaceable advantages: ‘I wouldn’t want to have something like that being the sole thing available … it’s important that actual human contact is involved in these things, because it will itself break cycles that become self-reinforcing.’ (participant 1)

Discussion

Our findings elucidate factors that may contribute to inequalities in treatment satisfaction and outcomes between sexual minority and heterosexual service users (Blosnich, Citation2017; Rimes et al., Citation2019). Rejection sensitivity and concealment may operate irrespective of whether a healthcare professional possesses or articulates prejudices towards service users. Consequently, the mere absence of prejudice and discrimination may not be sufficient to relieve service users’ concerns. In addition, practitioners may unintentionally create barriers to effective therapeutic relationships. Far from the therapeutic alliance being a setting in which participants can counter the minority stress processes which may be affecting their mental health, practitioners may inadvertently permit, recreate and reinforce them by pathologising minority sexuality, relying on stereotypes, erasing sexual minority identities, displaying limited knowledge about sexual minorities and/or avoiding discussion of sexuality.

Our study triangulates these findings using a different means of data collection, and explores in greater depth how such experiences affected the therapeutic relationship. This revealed that negative experiences in therapy relating to service users’ sexualities have the potential to affect service users’ appraisals of the entire therapeutic relationship. In other words, sexuality-based barriers may undermine the key elements necessary for any successful therapeutic relationship, such as empathy, trust, positive regard and engagement in treatment (Norcross & Wampold, Citation2011).

Finally, our study emphasises the importance of research exploring sexual minority specific interventions, including evidence-based technological adjuncts, which may be advantageous in the context of limited resources (Pachankis et al., Citation2020). There is preliminary evidence suggesting that some service users benefit from modified psychotherapeutic approaches targeting minority stress processes (Burton et al., Citation2019; Pachankis et al., Citation2015; Pachankis et al., Citation2020).

Providers should assess the efficacy, cost-effectiveness and feasibility of such approaches. However, minority affirmative psychotherapies may be more effective in individuals exhibiting higher levels of minority stress (Millar et al., Citation2016), meaning practitioners should explore whether service users’ sexualities play a role in their presenting problems, and tailor treatment accordingly.

These findings underscore the need for local government, providers and public policy makers to acknowledge the specific needs of sexual minorities. Irrespective of whether practitioners believe they hold or express prejudices, the quality of their interactions with sexual minority service users may benefit from clear indicators of their intention to provide inclusive care. Our participants had a range of ideas as to how this can be operationalised. Additional practices include: symbols of inclusivity (e.g. rainbow badges or signs); representations of sexual minorities in materials; and clearly articulated equality statements, confidentiality policies and feedback procedures. Our interviews also highlight a need for practitioners to be culturally competent with respect to sexual minorities, and capable of recognising and exploring whether and how minority stress processes impact service users and the process of therapy itself.

Limitations

Participants volunteering for this study may not be representative of all sexual minorities trying to access talking therapies for common mental health problems. Those with very positive experiences may have been less likely to volunteer, and our study is not representative of the sizeable proportion of sexual minority people who do not openly identify as such (Pachankis & Branstrom, Citation2019). Stigma concealment can have a powerful negative effect on sexual minority wellbeing (Pachankis, Citation2007) and therapeutic settings may have the potential to serve as the first space in which ‘closeted’ sexual minorities feel safe to disclose their sexuality. In addition, sexual-minority populations are heterogeneous, and sexuality intersects with other dimensions of identity (e.g. gender identity and race/ethnicity) to shape an individual’s experience (Jackson et al., Citation2020). While our study focusses on broad themes common to all sexual minorities, grouping together different sexual orientations may conceal important differences. Consequently, there is a need for future research focussing on sexual minority subgroups.

Conclusions and future directions

Our research focussed particularly on service users’ views on barriers to care and perspectives on service development, to gather information about possible contributors to outcome disparities. While not all participants reported negative service use experiences, many participants in our study reported barriers to optimal care which may undermine treatment satisfaction and outcomes. Nevertheless, barriers to effective therapeutic relationships may be only one component in a broader picture of determinants of disproportionately poor mental health. Consequently, future research should explore the extent to which the barriers reported in our study play a causal role in disparities in treatment satisfaction and outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Beard, C., Kirakosian, N., Silverman, A. L., Winer, J. P., Wadsworth, L. P., & Björgvinsson, T. (2017). Comparing treatment response between LGBQ and heterosexual individuals attending a CBT- and DBT-skills-based partial hospital. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(12), 1171–1181. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000251

- Blosnich, J. R. (2017). Sexual orientation differences in satisfaction with healthcare: Findings from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2014. LGBT Health, 4(3), 227–231. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2016.0127

- Bränström, R., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Tinghög, P., & Pachankis, J. E. (2018). Sexual orientation differences in outpatient psychiatric treatment and antidepressant usage: Evidence from a population-based study of siblings. European Journal of Epidemiology, 33(6), 591–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-018-0411-y

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Burton, C. L., Wang, K., & Pachankis, J. E. (2019). Psychotherapy for the spectrum of sexual minority stress: Application and technique of the ESTEEM treatment model. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 26(2), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2017.05.001

- Chakraborty, A., McManus, S., Brugha, T. S., Bebbington, P., & King, M. (2011). Mental health of the non-heterosexual population of England. British Journal of Psychiatry, 198(2), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.082271

- Cochran, S. D., Björkenstam, C., & Mays, V. M. (2017). Sexual orientation differences in functional limitations, disability, and mental health services use: Results from the 2013-2014 National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(12), 1111–1121. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000243

- Donahue, J. M., DeBenedetto, A. M., Wierenga, C. E., Kaye, W. H., & Brown, T. A. (2020). Examining day hospital treatment outcomes for sexual minority patients with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(10), 1657–1666. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23362

- Elliott, M. N., Kanouse, D. E., Burkhart, Q., Abel, G. A., Lyratzopoulos, G., Beckett, M. K., Schuster, M. A., & Roland, M. (2015). Sexual minorities in england have poorer health and worse health care experiences: A national survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2905-y

- Ferlatte, O., Salway, T., Rice, S., Oliffe, J. L., Rich, A. J., Knight, R., Morgan, J., & Ogrodniczuk, J. S. (2019). Perceived barriers to mental health services among Canadian sexual and gender minorities with depression and at risk of suicide. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(8), 1313–1321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00445-1

- First, M. B., Williams, J. B. W., Karg, R. S., & Spitzer, R. L. (2015). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5: Research Version. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- Foy, A. A. J., Morris, D., Fernandes, V., & Rimes, K. A. (2019). LGBQ + adults’ experiences of improving access to psychological therapies and primary care counselling services: Informing clinical practice and service delivery. Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 12, e42. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X19000291

- Jackson, S. D., Mohr, J. J., Sarno, E. L., Kindahl, A. M., & Jones, I. L. (2020). Intersectional experiences, stigma-related stress, and psychological health among black LGBQ individuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(5), 416–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000489

- King, M., Semlyen, J., Tai, S. S., Killaspy, H., Osborn, D., Popelyuk, D., & Nazareth, I. (2008). A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-8-70

- Mccann, E., & Sharek, D. (2014). Survey of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people’s experiences of mental health services in Ireland. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 23(2), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12018

- Millar, B. M., Wang, K., & Pachankis, J. E. (2016). The moderating role of internalized homonegativity on the efficacy of LGB-affirmative psychotherapy: results from a randomized controlled trial with young adult gay and bisexual men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(7), 565–570. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000113

- Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2011). Evidence-based therapy relationships: Research conclusions and clinical practices. Psychotherapy (Chicago, IL), 48(1), 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022161

- Pachankis, J. E. (2007). The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin, 133(2), 328–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.328

- Pachankis, J. E., & Branstrom, R. (2019). How many sexual minorities are hidden? Projecting the size of the global closet with implications for policy and public health. PLoS One, 14(6), e0218084. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218084

- Pachankis, J. E., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Rendina, H. J., Safren, S. A., & Parsons, J. T. (2015). LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 875–889. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000037

- Pachankis, J. E., McConocha, E. M., Clark, K. A., Wang, K., Behari, K., Fetzner, B. K., Brisbin, C. D., Scheer, J. R., & Lehavot, K. (2020). A transdiagnostic minority stress intervention for gender diverse sexual minority women’s depression, anxiety, and unhealthy alcohol use: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(7), 613–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000508

- Pachankis, J. E., Williams, S. L., Behari, K., Job, S., McConocha, E. M., & Chaudoir, S. R. (2020). Brief online interventions for LGBTQ young adult mental and behavioral health: A randomized controlled trial in a high-stigma, low-resource context. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(5), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000497

- Plöderl, M., Kunrath, S., Cramer, R. J., Wang, J., Hauer, L., & Fartacek, C. (2017). Sexual orientation differences in treatment expectation, alliance, and outcome among patients at risk for suicide in a public psychiatric hospital. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 184-197. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1337-8

- Plöderl, M., & Tremblay, P. (2015). Mental health of sexual minorities. A systematic review. International Review of Psychiatry (Abingdon, England), 27(5), 367–385. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1083949

- Rimes, K. A., Ion, D., Wingrove, J., & Carter, B. (2019). Sexual Orientation Differences in Psychological Treatment Outcomes for Depression and Anxiety: National Cohort Study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(7), 577–589. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000416

- Zarrabian, S., Riahi, E., Karimi, S., Razavi, Y., Haghparast, A., Yoon, J. H., … Ciraulo, D. A. (2018). Structured clinical interview for DSM-5—Research Version (SCID-5 for DSM-5, Research Version; SCID-5-RV). Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 33(1).