Abstract

ALSPAC birth-cohort data were analysed to assess prospective associations between childhood gender nonconformity (CGN), childhood/adolescent abuse, and adulthood PTSD symptoms. Structural equation models assessed whether abuse mediated the relationship between CGN and PTSD. Sex and sexual orientation differences were investigated. For females, higher parent-rated CGN at 30, 42 and 57-months was associated with mother-reported abuse, self-reported physical/psychological abuse, and/or self-reported sexual abuse. Higher CGN at 30-months was associated with more PTSD symptoms at 23 years. Self-rated CGN in males and females, and parent-rated CGN in males, were not associated with abuse or PTSD. Sexual minority identification was associated with higher CGN and abuse and for females, PTSD symptoms. In females, the relationship between greater CGN at 30-months and PTSD symptoms was separately mediated by each abuse variable. Self-reported sexual abuse was no longer a significant mediator after sexual orientation adjustment. Self-reported physical/psychological abuse significantly mediated the association alone when it was entered together with mother-reported abuse, even after sexual orientation adjustment. In conclusion, childhood gender nonconformity in females may increase the risk for adult PTSD symptoms, possibly mediated by childhood abuse. In females, mediation of the relationship between CGN and PTSD by sexual abuse may be particularly relevant for sexual minority individuals.

Childhood gender nonconformity and PTSD

Childhood gender nonconformity (CGN) refers to the behaviour exhibited by children who do not follow the social norms expected of their assigned sex at birth. CGN has been found to be associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or trauma symptoms in some (e.g. D'Augelli et al., Citation2006; Roberts et al., Citation2012a, Citation2012b), but not all (D'Augelli et al., Citation2002) retrospective or cross-sectional research.

Gender nonconformity and sexual orientation differences in abuse experiences

Individuals with a history of abuse in childhood have a much higher prevalence of PTSD than those without (19.8% vs. 2.1%; Cromer & Sachs-Ericsson, Citation2006). Recalled or current CGN has been found to be associated with reports of abuse in childhood and adolescence in retrospective and cross-sectional designs (e.g. Bos et al., Citation2019; Roberts et al., Citation2012a; Roberts et al., Citation2013). The only previous study using a prospective longitudinal design found that both males and females displaying more CGN had similarly higher odds of experiencing parental physical/emotional maltreatment in childhood (Xu et al., Citation2020). However, this study only used assessments of abuse that occurred before 6 years, which was perpetrated by the mother or her partner and was reported by the mother.

CGN is associated with an increased likelihood of identifying as a minority sexual orientation in young adulthood (Li et al., Citation2017). Minority sexual orientation has also been found to be associated with an increased risk of childhood abuse (Xu et al., Citation2020) and PTSD (Roberts et al., Citation2012b).

Childhood gender nonconformity, abuse and PTSD

It has been hypothesised that abuse may account for the associations between CGN and PTSD or trauma symptoms. Only one study has directly investigated this in a general population sample. Roberts et al. (Citation2012a) found that increased exposure to retrospectively reported childhood abuse partially explained the increased risk of PTSD in those who retrospectively reported being the most gender nonconforming in childhood; this was still the case after adjusting for current sexual orientation. However, the study relied on retrospective self-reports of both CGN and childhood abuse. Furthermore, assessing causal relationships between these variables would require respecting their causal ordering, for example by fitting a mediation model, which this study did not do.

The present study

Previous research on associations between CGN, abuse and PTSD has relied on retrospective or cross-sectional methods, both of which have methodological limitations. Additionally, few of the previous longitudinal CGN studies have investigated sex differences in associations; something which previous longitudinal research has identified as important, (Warren et al., Citation2019). Therefore, longitudinal studies are needed to assess the associations between CGN, abuse and PTSD, as well as sex differences in these relationships, using more appropriate statistical methods to assess the casual chain between these variables.

Study aims and hypotheses

The present birth-cohort study investigated prospectively whether higher levels of CGN, derived from parent-rated (2–5 years) and self-rated (8 years) measures of gender-typed behaviours, were associated with mother- and self-reported abuse in childhood/adolescence, and with self-reported symptoms of PTSD at 23 years. The study also investigated whether abuse mediated any association found between gender-typed childhood behaviour and later PTSD symptoms. Sexual orientation in adolescence was included as a covariate in the mediation model. The effects of interactions between sex and CGN were also investigated.

It was hypothesised that:

Higher CGN would be associated with greater abuse in childhood/adolescence.

Higher CGN would be associated with more self-reported PTSD symptoms at 23 years.

The relationship between CGN and later PTSD symptoms would be significantly mediated via abuse.

Minority sexual orientation at 15 years would be associated with greater abuse and PTSD. The mediation effects of abuse on the relationship between CGN and PTSD symptoms would hold when the models were adjusted for sexual orientation at 15 years.

Methods

Sample

The sample was taken from a longitudinal birth-cohort study, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Pregnant women resident in and around the city of Bristol in Avon, UK, with expected dates of delivery from 1st April 1991 to 31st December 1992 were invited to take part in the study. The initial number of pregnancies enrolled was 14,541 (for these at least one questionnaire has been returned or a “Children in Focus” clinic had been attended by 19/07/1999). Of these initial pregnancies, there was a total of 14,676 foetuses, resulting in 14,062 live births and 13,988 children who were alive at 1 year of age. Following further recruitment, the total numbers increased to 15,454 pregnancies and 15,589 foetuses. Of these, 14,901 children were alive at 1 year and took part in any data collection after 7 years of age (Boyd et al., Citation2013; Fraser et al., Citation2013). More details can be found on the study website, which includes a fully searchable data dictionary and variable search tool (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/our-data/).

There were 7,148 females and 7,536 males who were alive at 1 year and who had data for at least one of the study variables. Most of the participants were white (95%) and most mothers were educated to O-level or above (30% below O-level, 35% O-level, and 35% A-level or above). The present analyses were based on subsets of these participants. The number of participants varied between analyses due to missing data.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee (see http://www.aslpac.bris.ac.uk) and for the analysis of secondary data by King’s College London College Research Ethics Committee (ref. PNM/14/15-67).

Measures

Parent-rated gender-typed behaviour

Parents completed the Pre-school Activities Inventory (PSAI; Golombok & Rust, Citation1993) at 30, 42 and 57 months to rate their child’s gender-typed behaviours (test-retest reliability of .66 for females and .62 for males). Scores were standardised according to the measure’s instructions. To derive a measure in which both sexes could be analysed together, at each time point standardised Z-scores were calculated separately for males and females, and for males, these scores were subtracted from 1. Higher scores reflected more gender nonconforming behaviour.

Child-rated gender-typed behaviour

At 8.5 years, children completed the Childhood Activities Inventory (CAI), a shortened 16-item version of the PSAI (split-half reliability .64 in both males and females; Golombok et al., Citation2008). Scores were standardised as above.

PTSD symptoms

At 23 years participants were asked whether they had ever experienced each of six ‘stressful life events’ (Weathers et al., Citation2013). Participants who answered ‘yes’ to any item completed the PTSD Checklist for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders −5 (PCL-5 for DSM-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013). This measure has strong reliability (α = .94) and convergent validity (r = .74 to .85; Blevins et al., Citation2015).

Mother-reported abuse

Mothers reported on their child’s experiences of being ‘physically hurt by someone’ or ‘sexually abused by someone’ (yes/no) and on whether ‘you/your partner were emotionally cruel’ or ‘you/your partner were physically cruel to your child’ (yes/no) at various time-points between 8 months and 11 years.

Self-reported abuse

Abuse experiences before 17 years were self-reported retrospectively at 22 years. Physical and psychological abuse experienced by an adult family member was assessed using eight items adapted from the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein et al., Citation2003). Sexual abuse experienced by any adult or older child was assessed using two items adapted from the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss & Gidycz, Citation1985; see Appendix 1).

Deriving latent variables measuring abuse

Latent variables were generated separately for the self-reported and mother-reported abuse items. For the four mother-reported abuse items, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) suggested a single factor solution. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) achieved an adequate fit (RMSEA .05, CFI .97, TLI .90). Standardised factor loadings ranged from .27 to .67. For the 20 self-reported abuse items, EFA suggested a two-factor solution: ‘self-reported psychological/physical abuse’ (good fit; RMSEA .08, CFI .99, TLI .95; standardised factor loadings .59 to .80) and ‘self-reported sexual abuse’. The latter demonstrated a very poor fit (RMSEA .45, CFI .68, TLI .04), likely due to the small number of positive responses (0.5–7.6%). Therefore, a binary variable was created indicating any vs no self-reported experience of sexual abuse.

Covariates

Sexual orientation

At 15.5 years, participants were asked which description ‘best fits how you think about yourself’; these were categorised into (Heterosexual (those responding ‘100% heterosexual’) versus Non-heterosexual (all other responses); Jones et al., Citation2017).

Demographic characteristics

At 32 weeks gestation, mothers reported their highest educational level (‘below O-level’ v ‘O-level’ v ’A-level or above’) and their child’s ethnicity (white v non-white).

Statistical analyses

Analysis was performed using Stata version 15.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Preliminary correlations and t-tests were used to assess the bivariate relationships between key variables. Linear regression models were fitted using structural equation modelling (SEM) to assess whether gender-typed behaviour and sex (IVs) were associated with PTSD symptoms at 23 years (DV) and with self-reported physical/psychological abuse and mother-reported abuse (DVs). Standardised coefficients were reported to allow comparison between models throughout. Binary logistic regression models were fit to assess whether gender-typed behaviour and sex (IVs) were associated with self-rated sexual abuse (DV). Linear regression models also assessed whether each type of abuse report was associated with PTSD symptoms. Finally, models assessed whether sexual orientation was associated with gender-typed behaviour, abuse and PTSD. These models were all adjusted for the mother’s education and the child’s ethnicity. The same models were fitted a second time with a sex by gender-typed behaviour interaction term (or sex by sexual orientation in the sexual orientation models) to assess whether the relationships were different for males and females. Models were run with robust standard errors to address heteroskedasticity.

Missing data

Preliminary correlations were assessed using complete-case analysis. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used to help account for missing data (see Appendix 2) in further analysis.

Mediation analysis

Mediation analysis was used to assess whether any associations found in the initial linear regressions between childhood gender-typed behaviour (predictor) and later PTSD (outcome) might be explained by abuse (mediator). With the exception of the univariate mediation model for self-reported sexual abuse (for which the ‘paramed’ programme in Stata was utilised to accommodate the binary mediator; Liu et al., Citation2014) all mediation models were fitted using SEM and robust standard errors to address heteroskedasticity. Standardised coefficients were used to allow model comparisons. 1,000 bootstrap replications were run to derive percentile 95% confidence intervals for the indirect, direct and total effects (Hayes & Rockwood, Citation2017). Self-reported sexual abuse was modelled as a single observed variable, while mother-reported abuse and self-reported physical/psychological abuse were modelled as latent variables.

Initially, separate univariate mediator models were run, each with a single abuse mediator to assess whether each type of abuse report mediated a significant proportion of the relationship between gender-typed behaviour and later PTSD. These were each run again adjusting for sexual orientation. Abuse measures that remained significant mediators were subsequently included together in a parallel mediation model. This model was fitted allowing for covariance between the two mediators and run again adjusting for sexual orientation.

Results

Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics are shown in Appendix 3. Females were less likely to report being heterosexual than males (86.3% vs. 91.3%) and had higher PTSD scores.

Preliminary analyses

For associations between demographic variables, abuse, PTSD and CGN, for the whole sample and for males and females separately, see Appendix 4.

Associations between gender-typed behaviour, sex, abuse, and PTSD symptoms

Gender-typed behaviour, sex and abuse

Self-rated gender-typed behaviour was not significantly associated with mother- or self-reported abuse. More nonconforming parent-rated gender-typed behaviour at 30, 42 and 57 months and male sex were significantly associated with more mother-reported abuse (see Appendix 5). The addition of a sex by gender-typed behaviour interaction term revealed that the relationships between gender-typed behaviour and mother-reported abuse were significant for females only at all time points (see ). There was a significant association between more nonconforming parent-rated gender-typed behaviour at 30 and 42 months and self-rated physical/psychological abuse for females only (see ).

Table 1. Separate effects for males and females for the association between gender-typed behaviour and abuse and PTSD symptoms.

More nonconforming parent-rated gender-typed behaviour at 30, 42 and 57 months and female sex were significantly associated with more self-reported sexual abuse. The addition of a sex by gender-typed behaviour interaction term revealed that these relationships were significant for females only (see ). These effect sizes were small.

Gender-typed behaviour, sex and PTSD symptoms

More nonconforming parent-rated gender-typed behaviour at 30 months (but not at 42 or 57 months) and female sex were significantly associated with more PTSD symptoms at 23 years (see Appendix 5). The addition of a sex by gender-typed behaviour interaction term revealed that the relationship between parent-rated gender-typed behaviour at 30 months and PTSD symptoms were significant for females only (see ). Self-ratings of gender-typed behaviour were not associated with PTSD symptoms.

Abuse and PTSD symptoms

More mother-reported abuse (β = 68.84 (32.99, 104.70), p < .001), self-reported physical/psychological abuse (β = 7.46 (5.76, 9.17), p < .001), and self-reported sexual abuse (β = 11.05 (8.45, 13.66), p < .001) were significantly associated with higher PTSD score at 23 years. The addition of an interaction term between sex and abuse revealed that these relationships were significant for both males and females (p’s < .011).

Associations between sexual orientation and abuse, PTSD symptoms and gender nonconformity

Regression models demonstrated that sexual minority identification was associated with higher PTSD scores, mother-reported abuse, self-reported physical/psychological abuse, self-reported sexual abuse and with more nonconforming parent-rated and self-rated gender-typed behaviour at all time points (see Appendices 6.1 and 6.2).

The addition of a sex by sexual orientation interaction term demonstrated that the association of sexual minority identification with higher PTSD scores and with self-rated physical/psychological abuse was significant for females only (see ). However, the association between sexual minority identification and mother-reported abuse was significant for males only. For sexual abuse, the association with sexual minority identification was significant for both males and females (see ). Minority sexual orientation was associated with parent-rated gender-typed behaviour for both males and females, while the relationship with self-rated gender-typed behaviour was significant for males only (see ).

Table 2. Separate effects for males and females for the association between sexual orientation at 15 years and abuse and PTSD symptoms.

Table 3. Separate effects for males and females for the association between gender-typed behaviour and sexual orientation at 15 years.

Mediation analysis

Univariate mediation models

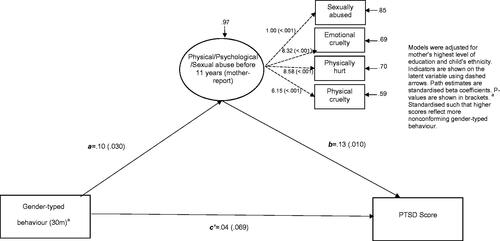

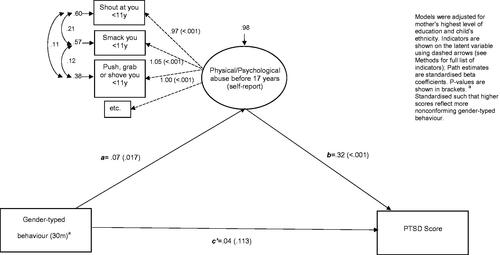

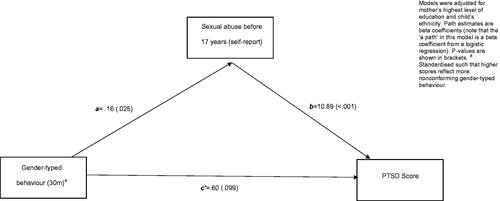

Univariate models demonstrated that the association in females between CGN at 30 months and PTSD was significantly mediated separately by mother-reported abuse (Appendix 7; indirect effect β = .013 (001, .024), p = .030; mediating 22.3% of the total effect), by self-reported physical/psychological abuse (Appendix 8; indirect effect β = .021 (.004, .038), p = .016; mediating 36.9%), and by self-reported sexual abuse (Appendix 9; indirect effect β = .198 (.064, .494), p = .038; mediating 24.8%). After sexual orientation adjustment, indirect effects remained significant for mother-reported abuse (β = .012 (.001, .023), p = .037; mediating 24.9%) and self-reported physical/psychological abuse (β = .016 (.0001, .032, p = .049; mediating 35.0%), but not for self-reported sexual abuse (β = .118 (−.068, .419), p = .270; mediating 13.2%). Therefore, only mother-reported abuse and self-reported physical/psychological abuse were included in the parallel mediator model.

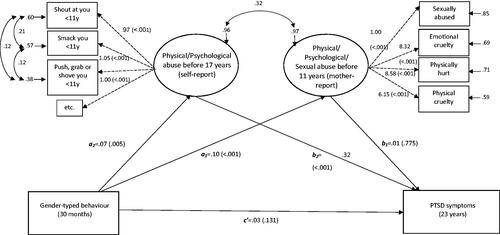

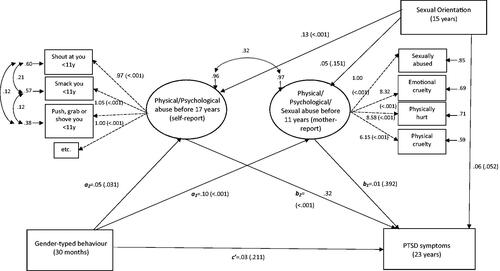

Parallel mediator models

An SEM was fitted to assess the result by including mother-reported abuse and self-reported physical/psychological abuse mediators in parallel (see ). This model had a very good fit (RMSEA .024, CFI .982, TLI .971). More nonconforming parent-rated gender-typed behaviour at 30 months had a significant total effect on higher PTSD symptoms (β = .059 (.013, .104), p = .011). The specific indirect effect through self-reported physical/psychological abuse (pathway a2b2; β = .022 (.006, .039), p = .008) significantly mediated 38.3% of the total effect. The specific indirect effect through mother-reported abuse (pathway a1b1), mediating 2.0% of the total effect, was not significant (β = .001 (−.006, .008), p = .749). The residual direct effect of gender-typed behaviour on PTSD symptoms (pathway c’) was non-significant (β = .035 (−.011, .081), p = .135).

Figure 1. SEM for the effect of gender-typed behaviour at 30 months on PTSD symptoms in females, mediated by self-reported physical/psychological abuse and mother-reported abuse. Indicators are shown on latent variables using dashed arrows. Curved arrows show covariances between errors. Path estimates are standardised beta coefficients. P-values are shown in brackets.

A second full parallel model was fitted, as above but also adjusting for sexual orientation (see ). This model had a very good fit (RMSEA .024, CFI .980, TLI .969). Again, more nonconforming parent-rated gender-typed behaviour at 30 months had a significant total effect on higher PTSD symptoms (β = .048 (.001, .094), p = .043). The specific indirect effect through self-reported physical/psychological abuse remained significant (β = .017 (.001, .034), p = .037), mediating 36.5% of the total effect. The specific indirect effect through mother-reported abuse, mediating 2.3% of the total effect, remained non-significant (β = .001 (−.005, .007), p = .722), and similarly the direct effect (pathway c’) was not significant (β = .029 (−.017, .075), p = .217).

Figure 2. SEM for the effect of gender-typed behaviour at 30 months on PTSD symptoms at 23 years in females, mediated by self-reported physical/psychological abuse and mother-reported abuse, adjusted for sexual orientation. Indicators are shown on latent variables using dashed arrows. Curved arrows show covariances between errors. Path estimates are standardised beta coefficients. P-values are shown in brackets.

Discussion

Associations between gender-typed behaviour, abuse and PTSD for females

For females, there was a small but significant association between more parent-rated masculine-typed behaviour at all timepoints and experiences of all types of childhood abuse reports, but there were no significant associations for self-rated gender-typed behaviours. Similarly, there was a small association between more parent-rated masculine-typed behaviour (at 30 months only) and self-reported PTSD symptoms at 23 years for females.

Multiple comparisons/chance findings could explain why only the 30-month CGN measure was significantly associated with PTSD symptoms in females. There are other possible reasons for this discrepancy. Children become more gender-typed as they grow older (Golombok et al., Citation2008). The 30-month measure may be the assessment least affected by the child’s attempts to conform to society’s gender-related expectations. The parent-rated measure relies on behaviours that are observable to them; it could be that it is this observable behaviour that makes children most at risk for abuse and subsequent PTSD. The self-ratings were also made much later (at 8 years) than the mother ratings (30–57 months). It could be that the differences in findings also reflect changes in gender-typed behaviour over time or differences in willingness to report gender-atypical behaviours between mothers and children. In sexual and gender minorities, it has been suggested that victimisation may lead to the concealment of a minority identity (Meyer, Citation2003), so it is possible that children may conceal their gender nonconformity as they get older.

All three abuse variables significantly mediated the association in females between CGN at 30 months and PTSD at 23 years when analysed separately. When both mother-reported abuse and self-reported physical/psychological abuse were included as mediators in parallel, only the latter remained a significant mediator, suggesting that mother-reports added little further information. Parents will not necessarily be aware of all the abuse experienced by their children and may be less willing to report abuse that implicates themselves or a family member.

Associations between gender-typed behaviour, abuse and PTSD for males

For males, gender-typed behaviour was not associated with abuse or PTSD. This contrasts with previous research (e.g. D'Augelli et al., Citation2006; Roberts et al., Citation2012a). It may be that previous studies have only found associations in males due to methodological limitations such as retrospective reports of CGN or less rigorous analysis. However, there are other possible explanations. In contrast to the measure of gender-typed behaviour used in the present study, all previous retrospective/cross-sectional studies utilised measures of self-perceived gender atypicality as their indicator for CGN. It is possible that different aspects of gender nonconformity are differentially associated with these outcomes.

PTSD scores were significantly higher in females than males, and there were higher rates of missing data for PTSD and self-reported abuse measures for males than females. These factors may make it harder to detect associations for males. There may also be sex differences in reporting abuse or PTSD.

Unlike the present study, but using the same birth cohort, Xu et al. (Citation2020) found a prospective association between more nonconforming parent-rated behaviour and mothers’ reports of emotional and physical abuse up to 6 years of age in both males and females. The present study had multiple maternal ratings up to the age of 11 years and included sexual or physical abuse by anyone, in addition to parental physical or emotional abuse. Therefore, associations may depend on the types, timings, perpetrators, or reporters of abuse investigated.

Associations between minority sexual orientation, abuse and PTSD

In line with previous research, the present study found significant associations between minority sexual orientation and abuse and PSTD. In females, significant mediation of the relationship between CGN and PTSD still held after adjusting for sexual orientation for mother-reported abuse and self-reported psychological/physical abuse. However, the proportion mediated was slightly reduced, similar to Roberts et al. (Citation2012a). The mediation by sexual abuse was no longer significant when adjusting for sexual orientation. Caution is needed in interpreting the extent of attenuation in relation to sexual orientation, in part due to the likely under-reporting of minority sexual orientation (Berg & Lien, Citation2006) and the relatively young age (15 years) of assessment. Gender nonconforming children may also be at elevated risk for abuse partly due to others’ perceptions of associations with minority sexual orientation, regardless of whether the individual themselves subsequently has a sexual minority identity.

Strengths and limitations

The study’s strengths include the large sample, prospective design and the inclusion of both parent-rated and self-rated gender-typed behaviour and abuse across multiple timepoints. Future research should investigate the mediation effects of different types of abuse using more diverse longitudinal samples with validated abuse measures. Effect sizes in this study were generally small, and caution should be taken in interpreting these results. However, given that this was a 21-year longitudinal study in a large representative sample, and that experiences of abuse and PTSD are likely to be under-reported, the relationships between gender-typed behaviour, sexual orientation, abuse and PTSD warrant further research.

Study implications

More research is needed into why CGN may put females specifically at risk for PTSD, investigating associations with a range of CGN and abuse measures at multiple time points. Those supporting gender-nonconforming females should be aware of their increased risk and any possible signs of abuse. As previous studies have found associations for males, those working with gender nonconforming males should also be vigilant for signs of abuse. Gender nonconforming young people may be at increased risk for victimisation due to perceptions of sexual minority identification (e.g. van Beusekom et al., Citation2016). Sexual minority orientation was also associated with abuse and PTSD in and of itself in the present study. Therefore, those working with young people should also be aware of the abuse and PTSD risk in sexual minority adolescents.

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses. The UK Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust (Grant ref: 102215/2/13/2) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. This publication is the work of the authors and they will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper. A comprehensive list of grants funding is available on the ALSPAC website (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf); this research was specifically funded by the MRC (Grant refs: MR/M006727/1; G0701594). AW is supported by the ESRC LISS DTP. This paper represents independent research part funded (KG) by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Berg, N., & Lien, D. (2006). Same-sex sexual behaviour: US frequency estimates from survey data with simultaneous misreporting and non-response. Applied Economics, 38(7), 757–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840500427114

- Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes, J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., Desmond, D., & Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

- Bos, H., de Haas, S., & Kuyper, L. (2019). Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adults: Childhood gender nonconformity, childhood trauma, and sexual victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(3), 496–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516641285

- Boyd, A., Golding, J., Macleod, J., Lawlor, D. A., Fraser, A., Henderson, J., Molloy, L., Ness, A., Ring, S., & Davey Smith, G. (2013). Cohort profile: The 'children of the 90s'-the index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys064

- Cromer, K. R., & Sachs-Ericsson, N. (2006). The association between childhood abuse, PTSD, and the occurrence of adult health problems: Moderation via current life stress. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19(6), 967–971. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20168

- D'Augelli, A. R., Grossman, A. H., & Starks, M. T. (2006). Childhood gender atypicality, victimization, and PTSD among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(11), 1462–1482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260506293482

- D'Augelli, A. R., Pilkington, N. W., & Hershberger, S. L. (2002). Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly, 17(2), 148–167. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.17.2.148.20854

- Fraser, A., Macdonald-Wallis, C., Tilling, K., Boyd, A., Golding, J., Davey Smith, G., Henderson, J., Macleod, J., Molloy, L., Ness, A., Ring, S., Nelson, S. M., & Lawlor, D. A. (2013). Cohort profile: The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children: ALSPAC Mothers cohort. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(1), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys066

- Golombok, S., & Rust, J. (1993). The pre-school activities inventory: A standardized assessment of gender role in children. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.131

- Golombok, S., Rust, J., Zervoulis, K., Croudace, T., Golding, J., & Hines, M. (2008). Developmental trajectories of sex-typed behavior in boys and girls: A longitudinal general population study of children aged 2.5-8 years. Child Development, 79(5), 1583–1593. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01207.x

- Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 98, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001

- Jones, A., Robinson, E., Oginni, O., Rahman, Q., & Rimes, K. A. (2017). Anxiety disorders, gender nonconformity, bullying and self-esteem in sexual minority adolescents: Prospective birth cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 58(11), 1201–1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12757

- Koss, M. P., & Gidycz, C. A. (1985). Sexual experiences survey: Reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(3), 422–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.53.3.422

- Li, G., Kung, K. T., & Hines, M. (2017). Childhood gender-typed behavior and adolescent sexual orientation: A longitudinal population-based study. Developmental Psychology, 53(4), 764–777. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000281

- Liu, H., Emsley, R., Dunn, G., VanderWeele, T., & Valeri, L. (2014). Paramed: A command to perform causal mediation analysis using parametric models. https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/paramed-a-command-to-perform-causal-mediation-analysis-using-parametric-models(24818a32-17ed-4076-a195-1b27a3fb1236)/export.html

- MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Roberts, A. L., Rosario, M., Slopen, N., Calzo, J. P., & Austin, S. B. (2013). Childhood gender nonconformity, bullying victimization, and depressive symptoms across adolescence and early adulthood: An 11-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(2), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.006

- Roberts, A. L., Rosario, M., Corliss, H. L., Koenen, K. C., & Austin, S. B. (2012a). Childhood gender nonconformity: A risk indicator for childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress in youth. Pediatrics, 129(3), 410–417. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1804

- Roberts, A. L., Rosario, M., Corliss, H. L., Koenen, K. C., & Austin, S. B. (2012b). Elevated risk of posttraumatic stress in sexual minority youths: Mediation by childhood abuse and gender nonconformity. American Journal of Public Health, 102(8), 1587–1593. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300530

- van Beusekom, G., Baams, L., Bos, H. M., Overbeek, G., & Sandfort, T. G. (2016). Gender nonconformity, homophobic peer victimization, and mental health: How same-sex attraction and biological sex matter. Journal of Sex Research, 53(1), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.993462

- Warren, A.-S., Goldsmith, K. A., & Rimes, K. A. (2019). Childhood gender-typed behavior and emotional or peer problems: A prospective birth-cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(8): 888–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13051

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov

- Xu, Y., Norton, S., & Rahman, Q. (2020). Childhood maltreatment, gender nonconformity, and adolescent sexual orientation: A prospective birth cohort study. Child Development, 91(4): e984-e994. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13317