Abstract

Background

To identify psychological interventions that improve outcomes for those who overdose, especially amongst Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex and Questioning populations.

Objective

To recognize and assess the results from all studies including randomized control trials (RCTs) that have studied the efficiency of psychiatric and psychological assessment of people who have depression that undergo non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) by self-poisoning, presenting to UK Accident and Emergency Departments.

Method

A scoping review of all studies including RCTs of psychiatric and psychological therapy treatments. Studies were selected according to types of engagement and intervention received. All studies including RCTs available in databases since 1998 in the Wiley version of the Cochrane controlled trials register in 1998 till 2021, Psych INFO, Medline, Google Scholar and from manually searching of journals were included. Studies that included information on repetition of the NSSI behaviour were also included. Altogether this amounts to 3900 randomized study participants with outcome data.

Results

Seven trials reported repetition of NSSI as an outcome measure which were classified into four categories. Problem-solving therapy is indicated as a promising therapy and has shown to significantly reduce repetition in participants who NSSI by overdosing than patients in the control treatment groups consisting of standard after care.

Conclusion

The data show that manualized cognitive therapy psychological intervention was more effective than TAU after care. However, these differences are not statistically significant with p = .15; CI 0.61, 1.0 which crosses the line of no effect. And psychodynamic interpersonal therapy is more effective than the standard treatment. Despite being only one study in this subgroup the analysis shows a statistical significance with p = .009, CI 0.08; 0.7.

Background

Literature reviews have shown that compared to cisgender heterosexual communities that Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex and Questioning (LGBTIQ) populations alongside non-binary people are 1.5 times more likely to suffer from mental health problems such as depression and twice as likely to end their lives by suicide (Bhugra et al., Citation2022; King et al., Citation2008; Marchi et al., Citation2022). Rates of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) figures are similarly increased but not much is known about the gradual aspects that lead to committing an NSSI. In some cases, the precipitating factors appear to be interpersonal difficulties as shown by Hawton et al. (Citation1998) but others refer to body image difficulties and substance misuse especially within lesbian and bisexual women (Bhugra et al., Citation2022). Difficulties in capturing the data pose a challenge ranging from questions raised for exploration to individual freedoms and how much monitoring information is needful (Coffman et al., Citation2017; Phillips et al., Citation2019). The Hawton et al. (Citation1998) review was restricted to gender binary populations and found that problem-solving therapies (PST) proved to be the most effective in reducing the NSSI behaviour repetition.

The figure for LGBTIQ and non-binary person who self-harms by overdosing remains unknown; however, in a Swedish study conducted using 70,000 participants between 1969 and 2010 found that LGBT people reported higher rates for NSSI than their cisgender heterosexual counterparts. Interestingly, the authors commented that those identifying as LGBT were more likely to be forthcoming on personal information than people who identified as cisgender heterosexual (Björkenstam et al., Citation2016). This supports the findings in the UK in a cross-sectional study by Slinn et al. (Citation2001) and a longitudinal New Zealand study (Salway et al., Citation2019; Skegg et al., Citation2003). Bränström and Pachankis (Citation2018) also verify that psychological distress features highly within the LGBTIQ population particularly in gay and bisexual men.

Little research is available on the graduation techniques or how one experiments leading to overdosing behaviour but the predisposing risk factors involve mental illness, non-white intersections of ethnic status, asylum seekers and, in some cases, minority stress (Carroll et al., Citation2014). The objective of this review is to evaluate which interventions might work for LGBTIQ and non-binary populations and if these differ from interventions delivered for cisgender heterosexual populations. Previously problem-solving techniques appeared to be the better option for cisgender heterosexual participants as the main precipitating factor being interpersonal difficulties. Several types of problems are identified as precipitating factors in patients that commit NSSI by overdosing. These commonly include interpersonal difficulties especially with a partner n = 28% and family members n = 44%, unemployment, financial, housing problems and social isolation (Gibbons et al., Citation1978; Hawton et al., Citation1998; Williams & Pollock, Citation2000; Muehlenkamp, Citation2006; Selby et al., Citation2012; Ani et al., Citation2017; Taylor et al., Citation2018).

These problems may link in with the minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003) as minority stress is a problem experienced by some within the LGBTIQ and non-binary community. The LGBTIQ and non-binary person experiencing stigma on a regular basis which affect the cognitive, emotional and behavioural functioning. Minority stress (Meyer, Citation2003) leads to many self-defeating behaviours like sexuality concealment, enforced straight-acting behaviours in order to conform to cisgender/heteronormative expectations, unprotected sex and compulsive sex activities to mediate the stress. These behaviours are commonly used alongside substance misuse as a coping strategy to alleviate high levels of stress. Some believe minority stress deserves to be a stand-alone diagnosis in the next DSM and ICD classifications publication (Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2008, Citation2009; Pachankis et al., Citation2015; Safren et al., Citation1999).

Importance of the review?

Hawton et al. (Citation1998) reviewed the evidence for the cisgender heterosexual populations and concluded by stating that problem solving was the most promising intervention. The studies used to aid Hawton et al. (Citation1998) to conclude on this point showed a high level of transparency. The outcome measure across the studies was the reduction of NSSI. In this review it would be prudent to use the same outcome measure, and also to explore whether minority stress is mentioned in the problem definition. MS is a specific problem because it links into identity and its concealment for survival. Previous reviews did not include an analysis to see if LGBTIQ and non-binary populations were included. Whilst they may have been a participant, they were not clearly identified as being LGB.

The interventions on offer in the studies are:

Manualized cognitive therapy (MACT) psychological intervention versus TAU after care – Studies with manualized CBT show a high adherence and efficacy when compared to other types of delivery. MACT is compared with treatment as usual which is typically an out-patients appointment with a mental health worker like a psychiatrist, nurse or psychologist generally lasting for up to 1 h.

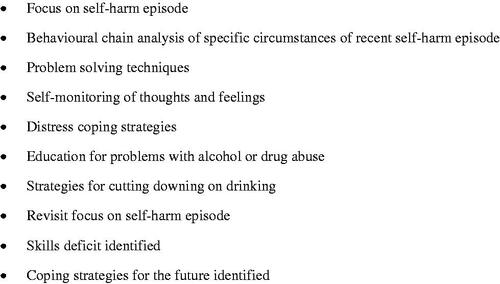

PIT versus standard treatment – PIT is brief therapy form provided to help with interpersonal difficulties. The time period for this is generally for a 6-month period. This might work as often the main reason for NSSI are interpersonal problems.

Intensive care plus standard treatment – The use of a crisis card in a 12-month period. This might work because it consisted of a CBT book prescription service. Up to six CBT books could be prescribed for the first group compared to the second group. The second group received face-to-face individual therapist sessions of CBT after they read CBT chapters on problem solving, thought management and managing difficult emotions.

Community doctor (GP) versus Community Mental Health Teams – GP’s following management of NSSI protocol and a referral to mental health services. This is a traditional route in the NHS and works for most cases but not for all. This might work because you have more than one person supervising the patient. A team approach brings each speciality and expertise availability for the patient.

Aim

To recognize and assess the results from all studies including randomised control trials that have studied the efficiency of psychiatric and psychological assessment of people who have depression that commit NSSI by self-poisoning, presenting to UK Accident and Emergency (A&E) Departments.

Method

The scoping review of all studies include randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychiatric and psychological therapy treatments. Studies were selected according to the types of engagement and intervention received. All studies including RCTs were available in databases since 1998 in the Willey version of the Cochrane controlled trials register in 1998 till 2021, Psych INFO, Medline, Google Scholar and from manually searching of journals. It included patients who commit NSSI by overdosing within a fixed period prior to entry into the study or RCT. It also included studies having the information on repetition of the NSSI behaviour. Altogether this amounts to 8024 randomized study participants with outcome data.

Criteria for considering studies for the review

Inclusion criteria: Studies were included within the review if they met the following criteria.

LGBTIQ and non-binary study participants aged 18 years And older have engaged in NSSI by overdose shortly before entry into study.

Studies must have reported repetition of NSSI as an outcome measure, thirdly study participants had to be randomised to treatment and control groups. If a qualitative study, then a decision was undertaken regarding the outcome measure and noted accordingly. Studies were included reporting any similarities between different types of psychiatric and psychological interventions, including standard after care. This was subject to availability and local resources and if the type of aftercare was clearly specified.

Studies were included if they assessed minority stress as part of the problem definition but herein lies the problem as MS is not a widely recognised problem. Studies which do not mention MS were also included because the minority group problems might have been noted but not specified as MS but instead formulated for example within a depression formulation.

Exclusion criteria: Studies with no A&E involvement and studies included in Hawton et al. (Citation1998) review as well as those focussing on suicide were excluded as were those published in other languages (i.e. not English).

Search methods for identification of studies

The search was performed in line with PRISMA criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies (Moher et al., Citation2009) to identify studies of participants who had presented to A&E departments and received psychological therapy.

Identification of relevant trials: A literature search was carried out by using electronic databases: (1) The electronic search process was replicated four times between November 2018 and April 2021. (2) The keywords used in search was Deliberate Self Harm, DSH, Non-Suicide Self Injury, NSSI, NSSID and LGBT; Self harm and LGBTIQ and non-binary and LGBT with RCT; Accident and emergency departments and self-harm studies.

Data collection and analysis

The following data were extracted from the articles like title, year; population sample; recruitment processes; sample size; alongside main findings and limitations of the study. The studies overall did not follow a theoretical model like minority stress (Meyer, Citation2003) but are therefore summarized in the results and discussion sections.

Results

Twenty-four studies were identified and were grouped as described in the methods section. But only seven studies were included in this review as the other 17 studies can be seen in Hawton et al. (Citation1998). Looking at the table summarizing the seven trials included in this review, their groupings, details and history of NSSI, the interventions used and the same quality of the concealment scores previously used in Hawton et al. (Citation1998). The data were assessed by the authors with the verification process in place. Quality of the studies was defined by transparency. illustrates four studies being given the score of 1 (for good transparency) and three studies scoring 3 (inadequate and not transparent). Blinding of the assessors were not stated or was unclear, only in one trial was fully reported. A total of 8024 patients had been randomized in the 24 trials, and outcome data regarding repetition of NSSI during follow up were available. The results of 17 trials can be seen using the older Cochrane measure for the assessment of risk in Hawton et al. (Citation1998) for the individual studies in terms of repetition of NSSI during follow up. shows studies since 1998. But as this is not a systematic review ROB 2 was not used to identify bias (Sterne et al., Citation2019). And finally, shows that the first two studies suffered a high attrition rate and NSSI incidence rate. But minority stress was not mentioned as a factor used for the assessment of the NSSI problem. Finally, and show the odds ratio showing Psychodynamic Interpersonal Therapy (PIT) is more effective than standard treatment. Despite being only one study in this subgroup the analysis shows a statistically Significance with p = 0.009, CI0.08; 0.7.

Table 1. All quantitative studies included in the scoping review of literature since 1998.

Table 2. Summary of outcome data in all the quantitative studies, i.e. review on repetition of NSSI.

Table 3. Looking at odds ratio overall, including all studies under review.

Table 4. Odds ratio for each group.

(Proportion (%) of participants who repeated behaviour, during follow up. MD = Missing data *Reported suicides).

The data show that MACT psychological intervention was more effective than TAU after care. However, these differences are not statistically significant with p = .15; CI 0.61, 1.0 which crosses the line of no effect.

PIT is more effective than standard treatment. Despite being only one study in this subgroup the analysis shows a statistical significance with p = .009, CI 0.08, 0.71. Standard care was more effective than intensive care plus outreach, but not statistically significant (p = .32; CI 0.85, 1.62). Community doctor (GP) was more effective than Community Mental Health Teams.

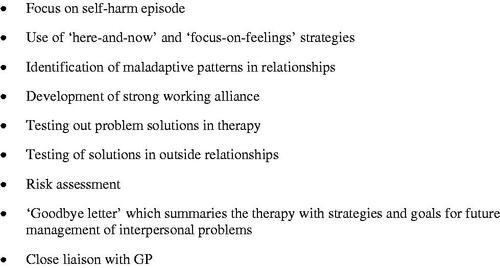

As can be seen in the key aspects of the MACT study (Evans et al., Citation1999) looking at MACT psychological intervention versus TAU after care.

Figure 1. Key aspects of manualized brief cognitively orientated or MACT psychotherapy for self-harm.

The largest study of problem solving carried was out by Tyrer et al. (Citation2003). Four hundred and eighty participants were randomly assigned between manualized treatment along with seven sessions with a therapist. Control (n = 241): Various problem-solving approaches, psychodynamic psychotherapy, GP or voluntary group referrals at 12 months showed no significant difference between those treated with MACT (39%) and treatment as usual (46%).

Weinberg et al. (Citation2006) showed a reduced rate in the repetition of NSSI during follow up in participants in the experimental group. N = 15 TAU and 15 = CBT with elements of DBT, which the researchers claim similar findings supported by Koons et al. (Citation2001) after 6 months of DBT, 92% decrease in frequency and by Turner (2000) after 3 months of DBT skills, an 84% decrease in frequency. However, the sample is small, was not a PIKO study and therefore the results are to be treated with caution. This, however, does show promise as the time scale traditionally assigned to DBT was in question with promising results of the decrease in outcome measure at 3 months.

As can be seen in the key aspects of PIT versus standard aftercare integrates the psychodynamic interpersonal and humanist approaches to therapy. In evaluating this second largest RCT of psychological treatment following NSSI, Guthrie et al. (Citation2001) had brief PIT in the experimental group and the control standard aftercare. The experimental group found significant reduction in suicidality at 6 months follow up compared with control. Repetition here included all self-reported acts of NSSI in addition to presentations to A&E departments. Half the total (n = 119) approached declined to have psychological treatment even when offered.

Intensive care plus outreach versus TAU standard aftercare in Evans et al. (Citation2005) showed that there is no benefit in providing participants with a crisis card. This allowed people to call in using a telephone service. There was no significance between the two groups at 12 months follow up. Low attrition and NSSI rates are reported in .

Community doctor (GP) versus Community Mental Health Teams – Bennewith et al. (UK 2002): Participants from 98 GP practices were selected from the NSSI register each having had a recent NSSI episode in the last 12 months. It concludes that 31% had contacted the GP following an episode of NSSI and 53% after 4 weeks. And 44% discharged from A&E were more likely than not to make contact after 4 weeks. But again there were low attrition and NSSI rates within the large sample. This study alongside Evans et al. (Citation2005) seemed to produce a lower repetition rate of the NSSI behaviour.

Discussion

This scoping review highlights that there is limited evidence that strongly supports any intervention, or indeed to make firm recommendations to help the LGBTIQ and non-binary patients that commit NSSI by overdosing. In nearly all trials since the study participants were recruited following a presentation to A&E departments due to NSSI. Some trials included study participants who had committed NSSI by overdosing only, whilst other methods of NSSI were not described. Unfortunately, none of the studies in this review addressed the problem defined as MS or traits of MS within the formulation. As the number of study participants are low in some treatment categories, results need to be treated with caution but does provide a direction to follow up.

It appears that the best evidence available in dealing with NSSI by overdosing participants is the psychodynamic study. The MACT approach with a particular focus on interpersonal problems showed no significance. Taylor et al. (Citation2018) produce further evidence to support this and although the content and context of problem-solving therapy varied between trials. The earliest by Evans et al. (Citation1999) was the first to place more overt emphasis on cognitive processes and procedures. A specific focus placed upon emotions, negative thinking together with a treatment manual. Features of the approach can be seen in (Evans et al., Citation1999).

The study had been repeated by Tyrer et al. (Citation2003) excluding patients with personality disorders and substance misuse difficulties, finding no significant difference between the MACT and standard aftercare. What it does suggest is that brief CBT is of limited efficacy in reducing NSSI by overdosing, but the findings taken in conjunction with the economic evaluation (Byford et al., Citation2003) indicate superiority of MACT over standardized aftercare in terms of cost and effectiveness combined.

This would support the meta-analysis of problem-solving techniques versus control conditions indicate positive results in other outcome measures not included in this scoping review by Townsend et al. (Citation2001). In reviewing six studies (Gibbons et al., Citation1978; Patsiokas & Clum, Citation1985; Hawton et al., Citation1987; Salkovskis et al., Citation1990; McLeavey et al., Citation1994; Evans et al., Citation1999), the results showed that PST were statistically significant in bringing improvement in scores for depression and hopelessness along with problem-solving ability, compared to control groups.

Promising significant evaluations were found for psychodynamic interpersonal study by Guthrie et al. (Citation2001) for interpersonal difficulties, which is a brief, easily taught form of treatment and therefore the skills are transferrable offering an advantage to A&E clinicians. But the studies exclude demographic data like LGBTIQ and non-binary populations which upon reflection of the current climate appears to be an outdated working practice. Thus, supporting the one size fits all approach which has no place in person centred care. Skills training reflecting and pinpointing solutions to include LGBTIQ and non-binary populations would be beneficial in measuring and reducing the impact of minority stress (Meyer, 1997). It could help A&E clinicians come to assess problems like transgender hate crimes or LGB gay bashings and violence with confidence.

Conclusion

At present evidence is lacking to indicate the most effective forms of treatment for NSSI-overdosing, in LGBTIQ and non-binary populations. This is a serious situation given the size of the population at risk and the risks of subsequent NSSI incidents pose. The best evidence available regarding psychological treatments supports the PST approach with a particular focus on interpersonal issues.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ani, J. O., Ross, A. J., & Campbell, L. M. (2017). A review of patients presenting to accident and emergency department with deliberate self-harm, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 9(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1234

- Bennewith, O., Stocks, N., Gunnell, D., Peters, T. J., Evans, M. O., & Sharp, D. J. (2002). General practice-based interventions to prevent repeat episodes of deliberate self-harm: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 324(7348), 1254–1257. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7348.1254

- Bhugra, D., Killaspy, H., Kar, A., Levin, S., Chumakov, E., Rogoza, D., Harvey, C., Bagga, H., Owino-Wamari, Y., Everall, I., Bishop, A., Javate, K. R., Westmore, I., Ahuja, A., Torales, J., Rubin, H., Castaldelli-Maia, J., Ng, R., Nakajima, G. A., … Ventriglio, A. (2022). IRP commission: Sexual minorities and mental health: Global perspectives. International Review of Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2022.2045912

- Björkenstam, C., Kosidou, K., Björkenstam, E., Dalman, C., Andersson, G., & Cochran, S. (2016). Self-reported suicide ideation and attempts, and medical care for intentional self-harm in lesbians, gays and bisexuals in Sweden. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(9), 895–901. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206884

- Bränström, R., & Pachankis, J. E. (2018). Sexual orientation disparities in the co-occurrence of substance use and psychological distress: A national population-based study (2008–2015). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(4), 403–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1491-4

- Byford, S., Knapp, M., Greenshields, J., Ukoumunne, O. C., Jones, V., Thompson, S., Tyrer, P., Schmidt, U., Davidson, K., & POPMACT Group (2003). Cost-effectiveness of brief cognitive behaviour therapy versus treatment as usual in recurrent deliberate self-harm: A decision-making approach. Psychological Medicine, 33(6), 977–986. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291703008183

- Carroll, R., Metcalfe, C., & Gunnell, D. (2014). Hospital presenting self-harm and risk of fatal and non-fatal repetition: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 9(2), e89944. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089944

- Coffman, K. B., Coffman, L. C., & Ericson, K. M. M. (2017). The size of the LGBT population and the magnitude of antigay sentiment are substantially underestimated. Management Science, 63(10), 3168–3186. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2503

- Davidson, K. M., & Tyrer, P. (1996). Cognitive therapy for antisocial and borderline personality disorders: single case study series. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35(3), 413–429. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1996.tb01195.x 8889082

- Evans, K., Tyrer, P., Catalan, J., Schmidt, U., Davidson, K., Dent, J., Tata, P., Thornton, S., Barber, J., & Thompson, S. (1999). Manual-assisted cognitive behaviour therapy (MACT): A randomised controlled trial of brief intervention with bibliotherapy in the treatment of recurrent deliberate self-harm. Psychological Medicine, 29(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/s003329179800765x

- Evans, J., Evans, M., Morgan, H. G., Hayward, A., & Gunnell, D. (2005). Crisis card following self-harm: 12-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 187(2), 186–187. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.187.2.186

- Gibbons, J. S., Butler, J., Urwin, P., & Gibbons, J. L. (1978). Evaluation of a social work service for self-poisoning patients. British Journal of Psychiatry, 133(2), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.133.2.111

- Guthrie, E., Kapur, N., Mackway-Jones, K., Chew-Graham, C., Moorey, J., Mendel, E., Marino-Francis, F., Sanderson, S., Turpin, C., Boddy, G., & Tomenson, B. (2001). Randomised controlled trial of brief psychological intervention after deliberate self-poisoning. BMJ, 323(7305), 135–138. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7305.135

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., McLaughlin, K. A., & Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. (2008). Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(12), 1270–1278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Dovidio, J. (2009). How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science, 20(10), 1282–1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x

- Hawton, K., Townsend, E., Arensman, E., Gunnell, D., Hazell, P., House, A., & Van Heeringen, K. (1998). Psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for deliberate self-harm. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4.

- Hawton, K., McKeown, S., Day, A., Martin, P., O'Connor, M., & Yule, J. (1987). Evaluation of outpatient counselling compared with general practitioner care following overdoses. Psychological Medicine, 17(3), 751–761. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700025988

- Hawton, K., Arensman, E., Townsend, E., Bremner, S., Feldman, E., Goldney, R., Gunnell, D., Hazell, P., van Heeringen, K., House, A., Owens, D., Sakinofsky, I., & Träskman-Bendz, L. (1998). Deliberate self-harm: A systematic review of efficacy of psychosocial intervention and pharmacological treatments in preventing repetition. BMJ, 317(7156), 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7156.441

- King, M., Semlyen, J., Tai, S. S., Killaspy, H., Osborn, D., Popelyuk, D., & Nazareth, I. (2008). A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self-harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry, 8(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-8-70

- Koons, C. R., Robins, C. J., Lindsey Tweed, J., Lynch, T. R., Gonzalez, A. M., Morse, J. Q., Bishop, G. K., Butterfield, M. I., & Bastian, L. A. (2001). Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy, 32(2), 371–390. 10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80009-5

- Marchi, M., Arcolin, E., Fiore, G., Travascio, A., Uberti, D., Amaddeo, F., Converti, M., Fiorillo, A., Mirandola, M., Pinna, F., Ventriglio, A., … & Italian Working Group on LGBTIQ Mental Health (2022). Self-harm and suicidality among LGBTIQ people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2022.2053070

- McLeavey, B. C., Daly, R. J., Ludgate, J. W., & Murray, C. M. (1994). Interpersonal Problem-Solving skills training in the treatment of self-poisoning patients. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 24(4), 382–394.

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2006). Empirically supported treatments and general therapy guidelines for non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 28(2), 166–185. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.28.2.6w61cut2lxjdg3m7

- Pachankis, J. E., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Rendina, H. J., Safren, S. A., & Parsons, J. T. (2015). LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioural therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 875–889. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000037

- Patsiokas, A. T., & Clum, G. A. (1985). Effects of psychotherapeutic strategies in the treatment of suicide attempters. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 22(2), 281–290. 10.1037/h0085507

- Phillips, G., Beach, L. B., Turner, B., Feinstein, B. A., Marro, R., Philbin, M. M., Paul, S., Felt, D., & Birkett, M. (2019). Sexual identity and behavior among U.S. High School Students, 2005-2015. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(5), 1463–1479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-1404-y

- Royal College of Psychiatrists (2010). Self-harm, suicide and risk: Helping people who self-harm (College Report CR158).

- Safren, S. A., Heimberg, R. G., Horner, K. J., Juster, H. R., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (1999). Factor structure of social fears: The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 13(3), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(99)00003-1

- Salkovskis, P. M., Atha, C., & Storer, D. (1990). Cognitive behavioural problem solving in the treatment of patients who repeatedly attempt suicide: A controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 157(6), 871–876. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.157.6.871

- Salway, T., Ross, L. E., Fehr, C. P., Burley, J., Asadi, S., Hawkins, B., & Tarasoff, L. A. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of disparities in the prevalence of suicide ideation and attempt among bisexual populations. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(1), 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1150-6

- Selby, E. A., Bender, T. W., Gordon, K. H., Nock, M. K., & Joiner, T. E. Jr, (2012). Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) disorder: A preliminary study. Personality Disorders, 3(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024405

- Skegg, K., Nada-Raja, S., Dickson, N., Paul, C., & Williams, S. (2003). Sexual orientation and self-harm in men and women. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(3), 541–546. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.541

- Slinn, R., King, A., & Evans, J. (2001). A national survey of the hospital services for the management of adult deliberate self-harm. Psychiatric Bulletin, 25(2), 53–55. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.25.2.53

- Sterne, J. A. C., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., Cates, C. J., Cheng, H.-Y., Corbett, M. S., Eldridge, S. M., Emberson, J. R., Hernán, M. A., Hopewell, S., Hróbjartsson, A., Junqueira, D. R., Jüni, P., Kirkham, J. J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., … Higgins, J. P. T. (2019). RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

- Taylor, P. J., Jomar, K., Dhingra, K., Forrester, R., Shahmalak, U., & Dickson, J. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 759–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.073

- Townsend, E., Hawton, K., Altman, D. G., Arensman, E., Gunnell, D., Hazell, P., House, A., & Van Heeringen, K. (2001). The efficacy of problem-solving treatments after deliberate self-harm: Meta-analysis of randomised control trials with respect to depression, hopelessness and improvement in problems. Psychological Medicine, 31(6), 979–988. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291701004238

- Tyrer, P., Thompson, S., Schmidt, U., Jones, V., Knapp, M., Davidson, K., Catalan, J., Airlie, J., Baxter, S., Byford, S., Byrne, G., Cameron, S., Caplan, R., Cooper, S., Ferguson, B., Freeman, C., Frost, S., Godley, J., Greenshields, J., … Wessely, S. (2003). Randomised control trial of brief cognitive behaviour therapy versus treatment as usual in recurrent self-harm: The POPMACT study. Psychological Medicine, 33(6), 969–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291703008171

- Weinberg, I., Gunderson, J. G., Hennen, J., & Cutter, C. J. Jr, (2006). Manual assisted cognitive treatment for deliberate self-harm in borderline personality disorder patients. Journal of Personality Disorders, 20(5), 482–492.

- Williams, J. M. G., & Pollock, L. R. (2000). The international Handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. Wiley.