Abstract

The feelings and hopes of young people around the world are often neglected in policymaking and research, with consequences for both their wellbeing and the effectiveness of humanity’s response to the climate crisis. Many of them are distressed by climate change’s impacts, the inaction of political and corporate leaders, the ways other people respond to their feelings, and the lack of support they have to share their feelings or get involved in meaningful climate-related work. This paper is written by a group of twenty-three concerned young people from fifteen countries. It provides a first-hand account of our deepest feelings, how these feelings affect our daily lives, the support we want to help us cope, and our hopes for a radically more compassionate future. The results are particularly relevant to policymakers, mental health professionals, journalists, educators, and people working with young people more widely.

Introduction

The feelings and mental health of people around the world both influence and are influenced by the climate crisis (for an overview, see Lawrance et al., Citation2021). Climate change is already having wide-ranging impacts globally, including extreme weather events (such as floods, storms, wildfires and heatwaves) and gradual changes (such as sea-level rise) that affect lives, livelihoods, cultures and the systems that we rely on for good health such as food and water security (for the latest evidence, see IPCC, Citation2022). These impacts can bring up a range of uncomfortable feelings and mental health impacts for both the direct victims of these events and people who simply learn about them (Augustinavicius et al., Citation2021; Clayton, Citation2020; Pihkala, Citation2019a). Conversely, a person’s capacity to cope with the feelings that the crisis evokes can affect their ability to contribute towards much-needed activism, mitigation or adaptation efforts (Capstick et al., Citation2022; Van Valkengoed & Steg, Citation2019). At the moment, people seldom have support to understand and cope with these feelings, even where these skills are most needed, such as in disaster-prone environments or climate-related professions (Hickman, Citation2020).

The impacts of the climate crisis on the feelings and mental health of young people are particularly important for several reasons. For example, young people will need to live with and hear about impacts for the rest of their lives, despite their negligible contribution to causing the crisis (UNICEF, Citation2021); they are vulnerable to climate impacts due to their low incomes (Barford et al., Citation2021); they are regularly exposed to distressing information through social media from young ages (Parry et al., Citation2022); they rarely have the professional authority or personal resources to mobilize the solutions they want to see (Arora et al., Citation2022); and they are integral to long-term efforts to create more sustainable and inclusive societies (Benoit et al., Citation2022).

Young people are often the most vocal in calling for ambitious climate action, yet they are seldom supported to cope with their climate-related feelings (WHO, Citation2022). According to mental health professionals, the crisis-related worry, fear, helplessness, anger, frustration, grief and betrayal many young people feel are more often signs of their awareness and compassion than signs of ‘dysfunction’ (see, for instance, Hickman, Citation2020). However, without support to cope with their feelings, many young people experience disruptive mental health impacts, such as overwhelm, disrupted sleeping or eating patterns, difficulty planning for the future and various kinds of trauma (for discussion, see Clayton, Citation2020). Moreover, support is needed to help young people to cope with and learn from these feelings (Hamilton, Citation2022; Wullenkord et al., Citation2021). Research has been published on a wide-range of climate-related feelings and mental health impacts (e.g. fear- Ojala et al., Citation2021; grief- Cunsolo and Ellis, Citation2018; sorrow- Hamilton, Citation2022; guilt- Jensen, Citation2019; powerlessness- Wullenkord et al., Citation2021; betrayal- Hickman et al., Citation2021; vicarious trauma- Pihkala, Citation2019b; post-traumatic stress disorder- Sharpe and Davison, Citation2021).

The creativity and unique perspectives of many young people, along with their limited vested interest in the status quo, mean they can be catalytic in helping societies to mitigate and adapt to the climate crisis (Benoit et al., Citation2022). Unfortunately, young people are seldom given platforms by their governments or corporations to share their ideas, feelings and hopes, stifling potential for much-needed intergenerational collaboration (Arora et al., Citation2022; UNICEF, Citation2021). When young people find their own ways to share their views (for instance through conversations with their peers or attendance at protests), they are often unfairly viewed as naive, inexperienced and generally unable to aid decisions of such importance (Spajic et al., Citation2019). The lack of meaningful opportunities for young people to help address socio-environmental issues weakens humanity’s collective response, harms young people’s wellbeing, and amplifies the concerns they have about the future (Barford et al., Citation2021).

Many researchers recognize the importance of exploring young people’s experiences in the climate crisis, but young people (particularly from the global south and otherwise marginalized communities) seldom have the opportunity to share their feelings in their own words. Godden et al. (Citation2021)’s ground-breaking paper was co-written by young people from Western Australia. This paper is the first to be co-written by young people from such a wide range of countries around the world.

This paper was co-authored by a group of twenty-three concerned young people aged 16–29 from fifteen countries (referred to as ‘we’ or ‘us’ in this paper). We come from seven High Income countries (Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Poland, the United Arab Emirates and Republic of Korea), two Upper Middle Income countries (Jamaica and South Africa), and six Lower Middle Income countries (Nigeria, Egypt, Kenya, India, Vietnam and the Philippines). Four of us are 16–18, seven are 19–24, and twelve are 25–29. Four of us are school students, six of us are current university students, and thirteen of us have completed university degrees. Nineteen out of twenty-three of us have directly experienced climate impacts (such as heatwaves, wildfires, storms, floods, droughts and sea-level rise). Our vocations range from photography and poetry to marine biology, clinical psychology, psychotherapy, journalism, and using social media as a tool to raise awareness about solutions to the crisis. Most of us did not know each other before starting this project.

We wrote this paper to share the breadth and depth of our climate-related feelings and hopes, knowing them to be shared by many other young people around the world (see also Hickman et al., Citation2021). We hope to increase mutual understanding between people of different ages and backgrounds, rather than to perpetuate any unhelpful blaming or shaming. Our experiences and views are particularly relevant to climate policymakers, mental health professionals, and anyone else passionate about creating a better world.

Methodology

The paper was developed using a hybrid participatory action-research and stakeholder analysis method where we contributed as both the authors and ‘subjects’ (for overviews, see Brugha and Varvasovszky, Citation2000; Brydon-Miller, Citation1997).

We formed our research group to include diverse perspectives. Three young climate-emotion researchers from different countries led the project (JD, SW, and JU) with the support of a more senior researcher (EL) who gave advice and guidance throughout the project. The three young researchers publicized the opportunity to get involved in this project through social media posts with a link to an application form, and they made selections to maximize geographic and age diversity.

The twenty young people selected shared their feelings and preferences for how the paper would be written over three months through detailed questionnaires, four group workshops, and online discussion documents. Three young people (JD, SW and JU) young people (JD, SW and JU) facilitated the involvement of the other young people and drafted the paper with the senior author to reflect all of the young people’s views, having synthesized their input through careful and iterative extraction of key themes and examples. All authors were involved in several rounds of input and feedback throughout the project.

Results

Despite our diversity in geography and experiences, our feelings, the ways we wanted to be supported to cope with our feelings, and our hopes moving forward are aligned. No major differences in our feelings were identified while writing this paper. A small number of minor differences we noticed are mentioned (for instance, where the intensity or primary reasons for holding certain feelings differed between people from different countries).

Our feelings and mental health amidst climate change’s impacts and climate inaction

This sub-section discusses our feelings in the climate crisis and their impacts upon our mental health. We refer to our conscious ‘feelings’ in a similar way to other researchers use the term ‘emotions’. This choice was made as a group due to the frequency with which the word ‘emotional’ is used to invalidate a person’s experiences (see the discussion in Pihkala, Citation2022). We use the term 'mental health’ to refer to our wellbeing, daily functioning and ability to cope with challenges in life and society. Our decision to use a broad definition of mental health reflects our belief that good mental health includes an emotional capacity and desire to contribute towards addressing issues in society, rather than simply the absence of a diagnosable ‘disorder’ (for a similar view, see WHO, Citation2018).

Despite our diversity, we share a wide range of deeply uncomfortable climate-related feelings, including worry, sorrow, grief, fear, anger, hopelessness and responsibility. These feelings tend to persist over time, increasing when we experience climate impacts, when we hear of them happening overseas, or when we are reminded of the inaction of political and corporate leaders. Our experiences reflect the findings of the climate-emotion researchers cited throughout this paper in many ways (cf. Nairn, Citation2019; Verlie, Citation2019).

Climate impacts make us sad and worried. Many of us can vividly describe tragic experiences of heatwaves, droughts, floods and storms which have destroyed livelihoods, families, communities and homelands. Those of us in low-lying countries (such as the Philippines and Jamaica) despair that our homeland may not even be habitable in the future due to sea-level-rise, storms and floods, with our leaders already forced to consider plans to relocate entire communities abroad. On the other hand, those of us in (or with family in) drought-prone regions of India, Egypt, Nigeria and Kenya fear the impacts of drought and famine on the wellbeing of people in our communities; many subsistence farmers, in particular, end up dying by suicide (see Thomas & De Tavernier, Citation2017).

Even those of us in privileged positions not currently vulnerable to climate impacts still experience the same kind of distressing feelings (such as grief, anger and worry) as we hear about impacts on other communities. Increasingly, however, even the richest and supposedly least vulnerable countries we live in are starting to experience significant climate impacts, such as floods, heatwaves and wildfires in the UK and Republic of Korea, or tropical cyclones in the USA and Canada (see IPCC, Citation2022).

The feelings we experience are linked not just to climate change’s impacts, but to how we see people (particularly in positions of power) acting in response to the crisis. When we believe peers, fellow citizens, business owners, and political leaders are taking it seriously it gives us a sense of connection, comfort and relief. However, when we believe people are responding without sufficient urgency, we feel despair about the unnecessary harm being caused, angry at the injustice being inflicted by the world’s richest people (particularly on the world’s poorest, vulnerable and marginalized groups), fearful of impacts occurring in the future, and unimportant – as if our concerns and future quality of life do not matter (see also Hickman et al., Citation2021).

The disruption caused by our climate-related feelings

Our feelings also disrupt our daily lives, particularly in the absence of support to cope (Clayton, Citation2020; Hickman, Citation2020). Knowing how much unnecessary harm is being caused, we can find it difficult to engage with basic tasks such as relaxing, sleeping, studying or working. Some of us also struggle with exorbitant feelings of guilt about our carbon footprints (even in poorer countries with relatively small footprints such as Vietnam), despite our understanding that the structures and systems we live in making ethical choices extremely difficult. In the absence of meaningful ways to contribute to climate action at structural levels, it can be hard to know how to navigate our desire to help, and many of us can struggle with feelings of shame and frustration about this too (cf. Berry et al., Citation2018; Jensen, Citation2019; Supran & Oreskes, Citation2017).

Our feelings can also impact our relationships and working lives. In our relationships, we wrestle with whether or not to discuss these feelings with our families, peers or colleagues, unsure about whether opening up will do more harm than good. We understand, for instance, that many people dismiss our concerns to avoid acknowledging the reality of climate change themselves (for discussion, see Weintrobe, Citation2021). We also debate with ourselves and our partners whether or not to have children, both because of the stress humanity is already putting upon the planet and because we are concerned about the quality of life our children may have (see also Schneider-Mayerson & Ling, Citation2020).

In climate-related work, activism or volunteering we may struggle with burnout, overwhelm and vicarious trauma as we try to overcome other people’s neglect of the climate crisis by working extremely hard ourselves (Nairn, Citation2019; Pihkala, Citation2019a). Alternatively, we may struggle with feelings of meaninglessness and guilt when we work for organizations that are ignorant to (or complicit in) the unfolding climate crisis (for discussion, see Jensen, Citation2019). Unfortunately, some of us (along with the vast majority of our wider peer groups) have often found working for the latter group of organizations unavoidable due to the lack of appropriately-paid climate-related work opportunities (Spajic et al., Citation2019).

The aforementioned examples demonstrate that our climate-related feelings can be intense and even deeply disruptive. However, rather than being signs of dysfunction, uncomfortable climate-related feelings often have enormous value; for instance, worry as a warning of potential threats, anger as a rejection of injustice, and grief as a healthy recognition of loss (Hamilton, Citation2022). Together, our climate-related feelings connect us to like-minded people around the world, they motivate our action, they remind us of our care for both other people and the natural world, and they guide us as we think about the better future we would like to create (see also Hickman, Citation2020). Moreover, many reputable mental health professionals and organizations argue that we must learn to cope with our climate-related feelings, rather than trying to ‘avoid’ all of our climate-related feelings altogether (APA, Citation2016; Cunsolo & Ellis, Citation2018; Lawrance et al., Citation2021; Ojala et al., Citation2021; WHO, Citation2022).

What helps us cope with our climate-related feelings and what creates unnecessary distress

A wide range of actions can be taken to help young people like us to cope with our feelings; these actions include small validating gestures that can be done by anyone in our lives; emotional support in education, activist or disaster-response settings; or, of course, people in positions of power taking climate action seriously (Hamilton, Citation2022; Nairn, Citation2019; Ojala et al., Citation2021).

Validating responses

Even if a person does not share our climate-related feelings with the same intensity, if they acknowledge our feelings as important, understandable and real, it helps us to feel seen, heard and cared for. Allowing us to share these feelings without an expectation of judgement, helps us to accept these feelings and to move forward positively (see also Godden et al., Citation2021; Hamilton, Citation2022).

When someone consistently invalidates our feelings then this creates additional distress that we must learn to cope with. We all encounter people who believe our feelings are invalid, unimportant, and not based on legitimate concerns about the world. If we do share our feelings, people often try to convince us that we are overreacting to the climate crisis, that it is ‘not that serious’, or that we should ‘focus on more positive things instead’ (which researchers such as Weintrobe, Citation2021, liken to disavowal). Responses like these lead us to feel disconnected from and unappreciated by the other person. Many of us so regularly experience invalidating responses that we feel we have been ‘gaslighted’ – as if there is something wrong with us for caring about the unjust impacts and roots of the crisis (see also Kaijser & Kronsell, Citation2014).

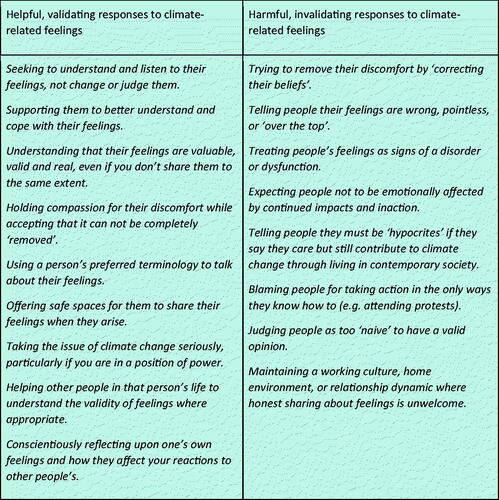

We offer examples of helpful and harmful ways to respond to a person’s feelings in .

Support from mental health professionals

Mental health professionals (such as researchers, counsellors and psychiatrists) can be particularly influential in helping us to cope with our feelings. They are not only well-equipped to design and hold non-judgmental spaces for people to share their deepest feelings (such as workshops, listening circles, community support groups or individual therapy sessions), but they are also often seen as authority figures that can help other people to understand the validity and value of a person’s feelings (Rust, Citation2020). They can also help people to raise awareness about the terminology that people may want to use, such as ‘eco-anxiety’, ‘solastalgia’, or simply ‘climate-related feelings’ (for discussion, see Pihkala, Citation2022). Unfortunately, many mental health professionals still invalidate their clients’ climate-related feelings, with deeply harmful effects (similar experiences have been recorded in earlier literature e.g. Stoknes, Citation2015).

Climate action from policymakers and business leaders

Policymakers and business leaders can help us cope by showing genuine commitment and taking meaningful, binding action, particularly at structural levels (for a discussion of systems thinking in the climate crisis, see Berry et al., Citation2018; for an account of other young people requesting structural changes, see Godden et al., Citation2021). Many of our feelings (such as sadness, worry, grief and frustration) derive their intensity from the knowledge that the crisis is still not being taken seriously enough. If policymakers were more ambitious then we would only need to grieve the impacts that are already ‘locked-in’, rather than feeling worried and angry about the potential scale and impacts of continued climate neglect (Ojala et al., Citation2021).

When policymakers neglect to take mitigating or adapting to the climate crisis seriously (including appropriate compensation for damages from the world’s richest countries to the poorest countries), we all experience unnecessary distress- particularly those of us from countries unable to protect themselves sufficiently without foreign assistance (Barford et al., Citation2021; IPCC, Citation2022).

What we hope for: a radically more compassionate world

We all believe a significantly better future is possible. We highlight here four of our hopes: (1) political support for climate action; (2) climate-related mental health support; (3) intergenerational collaboration; and (4) a radically more compassionate world more broadly.

Political support for climate action

The physical and mental health impacts of the crisis demand significantly more ambition in mitigation and adaptation efforts (including transnational efforts to support those communities most affected by the crisis). When impacts occur, they cause both loss of life and a wide variety of disruptive impacts for their direct victims and people who know them (cf. Clayton, Citation2020; Pihkala, Citation2019a). We hope for political action at all levels to ensure further climate change is minimized, the countries most affected are adequately supported by richer nations, and perverse business incentives are corrected (Berry et al., Citation2018).

Climate-related mental health support

Even small gestures of solidarity and kindness can make a significant difference to a person’s ability to cope with their feelings. Community-based and culturally-sensitive supports would further improve wellbeing outcomes and humanity’s collective response to the crisis (Godden et al., Citation2021; Hickman, Citation2020). Target groups could include young people, students, climate professionals, policymakers, and people working in industries which contribute heavily to the crisis. These supports may take a wide range of forms, such as community support/action groups, mental health support being included alongside environmental education, talking therapy, reflective journaling prompts, listening circles, or advice helplines.

In disaster response contexts, immediate and targeted culturally-sensitive mental health support is also needed to ensure all groups receive the support they need (for discussion, see Morganstein & Ursano, Citation2020; Palinkas et al., Citation2020). Even the most effective post-disaster support schemes to date tend to focus exclusively on physical health needs (e.g. shelter, food and medical care), neglecting the mental health needs of survivors (Massazza et al., Citation2021). These support schemes also often fail to reach marginalized groups in specific societies, such as women and poorer people (for discussion in the Bangladeshi context, see Nahar et al., Citation2014).

Our hopes for these climate-related mental health supports align with the recommendations of many other researchers (see also Clayton, Citation2020; Lawrance et al., Citation2021; Pihkala, Citation2019a). Many lists of currently available resources to help people cope with their climate-related feelings can be found online, though these resources are seldom included on wider mental health resource lists, they are not well documented in the academic literature, and they are typically underfunded, relying heavily on unpaid or underpaid work (Baudon & Jachens, Citation2021; Pihkala, Citation2019b).

The stigma which surrounds climate-related concern only increases the need for these interventions. Unwillingness to talk about the crisis exists in highly vulnerable countries (such as Jamaica, where older people may view extreme weather events as ordinary occurrences), in less vulnerable countries (such as the UK, where the climate crisis is often considered taboo and depressing to speak about), and even in climate-related professions (for instance, due to a lack of knowledge about the validity of climate-related feelings and the potential benefits of voicing them; Hickman, Citation2020).

Support for intergenerational collaboration

Meaningful intergenerational collaboration can help maximize use of the varied skills and experiences that people of different ages have (see Arora et al., Citation2022; Spajic et al., Citation2019). Currently, young people are often only involved in climate discussions tokenistically. For example, during COP26, many young activists felt they were involved by event organizers as ‘showboats’ but not actually listened to (Brown, Citation2022). At the same time, young people are often unfairly portrayed as the world’s ultimate saviours’ (Benoit et al., Citation2022) despite the lack of power that most young people have to affect the structural levels where action is most needed (Berry et al., Citation2018; Godden et al., Citation2021).

Currently, many of us are unable to contribute fully to addressing the climate crisis due, for example, to the lack of meaningful climate-related opportunities available and related financial, educational and mental health support barriers preventing our involvement (Hamilton, Citation2022; Spajic et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, many of us want to be involved in climate-related decision-making and careers, working collaboratively with other people to offer all that we can to help address the crisis.

A radically more compassionate world more broadly

Finally, we hope for a radically more compassionate world more broadly where values of inclusivity, humility, altruism, and collaboration are prioritized. Climate action, climate-related mental health support, and intergenerational collaboration are necessary parts of this more compassionate world, but they are also insufficient (for discussion of intersecting crises in the world, see Moore et al., Citation2021). Although our economic systems have many benefits, in their current state they also create the prime conditions for many distasteful consequences including not just the climate crisis, but also biodiversity loss, wars being fought over access to resources, extreme financial inequality, and mental health challenges such as anxiety, depression and work-related burnout (Dabla-Norris et al., Citation2015; Thanem & Elraz, Citation2022).

The better world we want must be built on a foundation of more compassionate systems (Berry et al., Citation2018). We believe investing resources to improve our underlying political, corporate and education systems will be more effective than responding to crises at the surface or ‘symptoms’-level. Perverse incentives within governments, businesses and education must be acknowledged and responded to accordingly (Weintrobe, Citation2021). Many of the problems we face as a global society stem from unchallenged income-centric economic ideology and cultural narratives, suggesting a relatively small number of changes could significantly improve the lives of current and future generations (see Moore et al., Citation2021).

Implications for policy and practice

The implications of this paper relate to both humanity’s handling of the climate crisis and other crises more widely. They are particularly relevant to policymakers, mental health professionals, educators and journalists.

Responding to crises

The climate crisis, like other global crises, must be addressed with proportional, cross-sector mitigation and adaptation strategies to protect physical and mental health outcomes worldwide (IPCC, Citation2022; Roland et al., Citation2020). Richer countries must provide financial support to help poorer countries respond to the climate crisis, without suppressing the interests of those poorer countries or otherwise adopting problematic colonial ideologies (see Manzo, Citation2010; Porter et al., Citation2020).

Our response to crises must have both people and other parts of nature at their centre. The success of our responses must be measured by how they affect people and the planet we rely on (Godden et al., Citation2021). People of all ages and backgrounds should have their creativity, experiences and expertise valued; and they should be empowered to contribute meaningfully to the solutions we need (Arora et al., Citation2022). Financial and emotional support for both the victims of crises and those trying to address them must also be provided.

Action must be taken to address perverse political, business and education incentives where they exist. These perverse incentives created prime conditions for many crises in the world today. For example, at the moment, political parties seeking campaign funds are incentivized to cater primarily for the interests of wealthy elites rather than for all people equally (Elsässer et al., Citation2018); businesses often have a fiduciary duty to create or sidestep problems rather than address them (e.g. fast-fashion companies are incentivized to outsource production to countries with lax regulations- Bhardwaj and Fairhurst, Citation2010; and smartphone companies are incentivized to make their devices as addictive as possible- Pera, Citation2020); and education institutions are incentivized to educate students in the way that brings them the most money (e.g. via alumni donations or results-based government funding schemes) rather than to equip their students to help address societal problems (Dean & McLean, Citation2021). Addressing these incentives through structural policy change will bring disproportionate benefits compared to focussing solely on surface-level solutions (for discussion, see Berry et al., Citation2018; Moore et al., Citation2021).

Mental health support

Taking the above actions to address crises and to involve people in meaningful responses to them will yield significant mental health benefits. However, there are also other ways to support mental health in the face of these crises. These supports not only improve wellbeing outcomes but also can strengthen our collective response to crises (for discussion, see Hamilton, Citation2022; Lawrance et al., Citation2021).

Counsellors, psychotherapists and psychiatrists should explore their own feelings about crises to ensure their own denial, disavowal or fear do not adversely affect the support they provide clients. If they do this, they can consider expanding their work to include one-to-one or community support for people in communities vulnerable to impacts or in activist settings (Hamilton, Citation2022; Lawrance et al., Citation2021; Stoknes, Citation2015). Mental health training providers should also highlight the value of appropriate concern about issues in the world and help to end the pathologisation of compassionate people (APA, Citation2016; Stoknes, Citation2015; Weintrobe, Citation2021). To do this, mental health professionals must actively challenge the notion that the absence of uncomfortable feelings about the current state of the world (such as worry, sadness and frustration) is necessarily a sign of ‘good mental health’ and that the presence of these feelings suggests the presence of a ‘disorder’ (WHO, Citation2018). Indeed, the absence of strong feelings in response to upsetting global issues is more often a cause for psychotherapeutic concern than their presence (Hickman, Citation2020; Weintrobe, Citation2021). Environmental educators and journalists should also share climate-centred mental health support resources and information alongside triggering content (Hickman, Citation2020).

Grant providers should help finance the aforementioned efforts to avoid increasing the burnout climate change, mental health and teaching professionals often already feel (Pihkala, Citation2019a).

Strengths and limitations

This paper contributes the voices of twenty-three young people from fifteen countries to the academic literature on young people’s feelings, experiences and hopes in the climate crisis. To ensure cultural differences were acknowledged appropriately, young people from different countries were involved in questionnaires, workshops, synthesizing information into key themes and sharing feedback on the paper drafts. The paper is written in our own words, and highlights the feelings and hopes we felt were most important to highlight as young people growing up experiencing and observing devastating climate impacts not being responded to appropriately. It also includes insights previously underreported in academic literature, including the commonalities and differences between young people’s experiences around the world, the emotional support they want in the climate crisis, their desire for mutual understanding and collaboration between people of different backgrounds, and their desire for a better future more broadly (with implications extending beyond the climate crisis).

We can not claim to speak for all young people even in our own countries. We are each influenced by our own positionality, for instance, we are all English speakers with internet access and have greater-than-average experience researching and studying the climate crisis. More details about us are included in the introduction. Nevertheless, we understand that our experiences are shared by many other young people around the world and know that our feelings and hopes are validated by the many climate-aware mental health professionals cited throughout this paper. In future research, we suggest platforming voices from Indigenous communities, the South American continent, and other communities that we were not able to.

Conclusion

Allowing the climate crisis to go unchecked threatens the safety, mental health and dreams of young people around the world. Young people have not been given a fair say in the world that they have inherited. This paper provides a unique first-hand account of the feelings, experiences and hopes of twenty-three young people from fifteen countries. It provides a voice that we hope will be heard by policymakers, climate change professionals, and mental health professionals.

The paper supports and extends previous climate-emotion research. Despite our diversity, we share a wide range of deeply uncomfortable feelings in the climate crisis, which, particularly in the absence of support to cope, disrupt our daily lives. The paper includes a number of ways we can be supported to cope with our climate-related feelings: for example, anyone can help us to cope by showing a genuine care for our wellbeing, offering us spaces to share our feelings without judgement, and taking the crisis seriously in their own professions. We also present four of our main hopes moving forward: climate action, climate-related mental health support, intergenerational collaboration and a radically more compassionate world more broadly (built on systems that value the protection of people and the rest of the natural world, now and in the future).

Like most people from older generations, we want a better world for our families, our peers, and our kids. We hope this paper raises awareness about the mental health impacts of continued climate inaction, normalizes healthy concern about the state of the world, and inspires people to imagine the better future we could be working towards together.

Author contributions

The authors contributed to various stages of the project. Twenty-three young authors from fifteen countries were involved (JD, SW, JU, SM, AO, DOJ, LHA, TS, PRM, HA, HR, KVA, JC, AS, KM, JK, NGM, LI, MB, TH, AW, AMRU and a young person from Vietnam who preferred to stay anonymous). Two authors (NGL and JK) have strong family ties to countries they no longer live in (Egypt and Poland). Three of the authors led the project (JD, SW and JU) with the support of a more experienced researcher (EL).

Acknowledgements

This paper would not have been possible without the support of various people and partners; Gareth Morgan and others gave us the idea to produce this paper; Professor Azeem Majeed helped us to secure funding for the project; Force of Nature, SustyVibes and other youth organizations helped recruit young people across the world; and Dr Mala Rao, Richard Powell, and Dr Neil Jennings oversaw the wider Special Issue in which this has been published.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychological Association (APA). (2016). Climate change is threatening mental health. Retrieved September 2, 2022, from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2016/07-08/climate-change

- Arora, R., Spikes, E. T., Waxman-Lee, C. F., & Arora, R. (2022). Platforming youth voices in planetary health leadership and advocacy: An untapped reservoir for changemaking. The Lancet. Planetary Health, 6(2), E78–E80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00356-9

- Augustinavicius, J. L., Lowe, S. R., Massazza, A., Hayes, K., Denckla, C., White, R. G., Cabán-Alemán, C., Clayton, S., Verdeli, L., & Berry, H. (2021). Global climate change and trauma: An International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Briefing Paper. Retrieved from https://istss.org/public-resources/istss-briefing-papers/briefing-paper-global-climate-change-andtrauma

- Barford, A., Mugeere, A., Proefke, R., & Stocking, B. (2021). Young people and climate change. COP26 Briefing Series of the British Academy, 2021, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5871/bacop26/9780856726606.001

- Baudon, P., & Jachens, L. (2021). A scoping review of interventions for the treatment of eco-anxiety. Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 18.

- Benoit, L., Thomas, I., & A., Martin. (2022). Ecological awareness, anxiety, and actions among youth and their parents–a qualitative study of newspaper narratives. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 27(1), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12514

- Berry, H. L., Waite, T. D., Dear, K. B., Capon, A. G., & Murray, V. (2018). The case for systems thinking about climate change and mental health. Nature Climate Change, 8(4), 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0102-4

- Bhardwaj, V., & Fairhurst, A. (2010). Fast fashion: Response to changes in the fashion industry. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 20(1), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593960903498300

- Brown, H. (2022). ’COP26 is a youth-washing project’, according to young activists participating in the conference. Retrieved July 29, 2022, from https://www.scotsman.com/news/environment/cop-26-is-a-youth-washing-project-say-young-activists-3445764

- Brugha, R., & Varvasovszky, Z. (2000). Stakeholder analysis: A review. Health Policy and Planning, 15(3), 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/15.3.239

- Brydon-Miller, M. (1997). Participatory action research: Psychology and social change. Journal of Social Issues, 53(4), 657–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1997.tb02454.x

- Capstick, S., Thierry, A., Cox, E., Berglund, O., Westlake, S., & Steinberger, J. K. (2022). Civil disobedience by scientists helps press for urgent climate action. Nature Climate Change, 12(9), 773–774. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01461-y

- Clayton, S. (2020). Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 74, 102263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263

- Cunsolo, A., & Ellis, N. (2018). Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nature Climate Change, 8(4), 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0092-2

- Dabla-Norris, E., Kochhar, K., Suphaphiphat, N., Ricka, F., & Tsounta, E. (2015). Causes and consequences of income inequality: A global perspective, report by the International Monetary Fund, Jun 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2015/sdn1513.pdf

- Dean, A., & McLean, J. G. (2021). Adopting measures to increase alumni donations at prestigious universities. International Journal of Business and Management, 16(12), 27. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v16n12p27

- Elsässer, K., Hence, S., & Schäfer, A. (2018). Government of the people, by the elite, for the rich: Unequal responsiveness in an unlikely case. MPIfG Discussion Paper No. 18/5. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/180215/1/1025295536.pdf

- Godden, N. J., Farrant, B. M., Farrant, J. Y., Heyink, E., Collins, E. C., Burgemeister, B., Tabeshfar, M., Barrow, J., West, M., Kieft, J., Rothwell, M., Leviston, Z., Bailey, S., Blaise, M., & Cooper, T. (2021). Climate change, activism, and supporting the mental health of children and young people: Perspectives from Western Australia. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 57(11), 1759–1764. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.15649

- Hamilton, J. (2022). Alchemizing sorrow into deep determination: Emotional reflexivity and climate change engagement. Frontiers, Collection, 2022, 786631. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.786631

- Hickman, C. (2020). We need to (find a way to) talk about … Eco-anxiety. Journal of Social Work Practice, 34(4), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2020.1844166

- IPCC. (2022). Summary for Policymakers [H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, M. Tignor, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem (eds.)]. In Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the Sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change [H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)], (pp. 3–33). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.001

- Jensen, T. (2019). Ecologies of guilt in environmental rhetorics. Palgrave Pivot.

- Kaijser, A., & Kronsell, A. (2014). Climate change through the lens of intersectionality. Environmental Politics, 23(3), 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.835203

- Lawrance, E., Thompson, R., Fontana, G., & Jennings, N. (2021). Grantham Institute Briefing Paper No 36: The impact of climate change on mental health and emotional wellbeing: Current evidence and implications for policy and practice, https://doi.org/10.25561/88568

- Hickman, C., Marks, P., Pihkala, E., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, E. R., Mayall, E. E., Wray, B., Mellor, C., & Van Susteren, L. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(12), e863–e873. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3

- Manzo, K. (2010). Imaging vulnerability: The iconography of climate change. Area, 42(1), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2009.00887.x

- Moore, K., Hanckel, B., Nunn, C., & Atherton, S. (2021). Making sense of intersecting crises: Promises, challenges, and possibilities of intersectional perspectives in youth research. Journal of Applied Youth Studies, 4(5), 423–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43151-021-00066-0

- Massazza, A., Brewin, C. R., & Joffe, H. (2021). Feelings, thoughts and behaviours during disaster. Qualitative Health Research, 31(2), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320968791

- Morganstein, J. C., & Ursano, R. J. (2020). Ecological disasters and mental health: Causes, consequences and interventions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00001

- Ojala, M., Cunsolo, A., Ogunbode, C., & Middleton, J. (2021). Anxiety, worry, and grief in a time of environmental and climate crisis: A narrative review. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 46(1), 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-022716

- Nahar, N., Blomstedt, Y., Wu, B., Kandarina, I., Trisnantoro, L., & Kinsman, J. (2014). Increasing the provision of mental health care for vulnerable, disaster-affected people in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health, 14, 708. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-708

- Nairn, K. (2019). Learning from young people engaged in climate activism: The potential of collectivizing despair and hope. YOUNG, 27(5), 435–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308818817603

- Palinkas, L. A., O’Donnell, M., Lau, W., & Wong, M. (2020). Strategies for delivering mental health services in response to global climate change: A narrative review. International Journal or Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 1–19.

- Parry, S., McCarthy, S. R., & Clark, J. (2022). Young people’s engagement with climate change issues through digital media – A content analysis. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 27(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12532

- Pera, A. (2020). The psychology of addictive smartphone behaviour in young adults: Problematic use, social anxiety, and depressive stress. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 573473. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.573473

- Pihkala, P. (2019a). The cost of bearing witness to the environmental crisis: Vicarious traumatization and dealing with secondary traumatic stress among environmental researchers. Social Epistemology, 34(1), 86–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2019.1681560

- Pihkala, P. (2019b). Climate anxiety, report for MIELI Mental Health Finland. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336937227_Climate_Anxiety

- Pihkala, P. (2020). Anxiety and the ecological crisis: An analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability, 12, 19.

- Pihkala, P. (2022). Towards a taxonomy of climate emotions. Frontiers in Climate, 3, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2021.738154

- Porter, L., Moloney, S., Bosomworth, K., & Verlie, B. (2020). Decolonising climate change adaptation. Planning Theory and Practice, May 2020.

- Roland, J., Kurek, N., & Nabarro, D. (2020). Health in the climate crisis: A guide for health leaders. World Innovation Summit for Health.

- Rust, M. J. (2020). Towards an ecopsychotherapy. Confer Books.

- Schneider-Mayerson, M., & Ling, L. K. (2020). Eco-reproductive concerns in the age of climate change. Climatic Change, 163(2), 1007–1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02923-y

- Sharpe, I., & Davison, C. M. (2021). Climate change, climate-related disasters and mental disorder in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. British Medical Journal Open Access, 11, 1-12.

- Spajic, L., Behrens, G., Gralak, S., Moseley, G., & Linholm, D. (2019). Beyond tokenism: Meaningful youth engagement in planetary health. The Lancet. Planetary Health, 3(9), e373–e375. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30172-X

- Stoknes, P. E. (2015). What we think about when we try not to think about global warming: Toward a new psychology of climate action. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Supran, G., & Oreskes, N. (2017). Assessing ExxonMobil’s climate change communications (1977–2014). Environmental Research Letters, 12(8), 084019. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab89d5

- Thanem, T., & Elraz, H. (2022). From stress to resistance: Challenging the capitalist underpinnings of mental unhealth in work and organizations. International Journal of Management Reviews, 2022, 12293.

- Thomas, G., & De Tavernier, J. (2017). Farmer-suicide in India: Debating the role of biotechnology. Life Science Social Policy, 13, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40504-017-0052-z

- UNICEF. (2021). The climate crisis is a child rights crisis: Introducing the Children’s Climate Risk Index. United Nations Children’s Fund.

- Van Valkengoed, A., & Steg, L. (2019). The psychology of climate change adaptation. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108595438

- Verlie, B. (2019). Bearing worlds: Learning to live-with climate change. Environmental Education Research, 25(5), 751–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1637823

- Weintrobe, S. (2021). Psychological roots of the climate crisis: Neoliberal exceptionalism and the culture of uncare (psychoanalytic horizons). Bloomsbury Academic.

- WHO (World Health Organisation) (2018). Mental health: Strengthening our response. Retrieved July 28, 2022, from http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

- WHO (World Health Organisation). (2022). Mental health and climate change: Policy brief. Retrieved July 28, 2022, from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240045125

- Wullenkord, M. C., Tröger, J., Hamann, K. S., Loy, L. S., & Reese, G. (2021). Anxiety and climate change: A validation of the climate anxiety scale in a German-speaking quota sample and an investigation of psychological correlates. Climatic Change, 168(3–4), 20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03234-6